Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 64

December 28, 2016

Shawn’s Question

In the Comments to an earlier post in this series, “Using Your Real Life in Fiction,” Shawn wrote:

Steve and Shawn at the Noho Star at Bleecker and Lafayette, NYC

My question, which I think a lot of writers will have is this …

Do you deliberately think of this stuff re: characters and their thematic roles, before you write your first draft?

Or do you save this analytical/editor thinking for later? And then go back and tighten it all up?

Great question, pard. Lemme answer with a confession of exactly how dumb I am.

A few years ago I wrote a novel called Killing Rommel. (No, it was NOT one of the Bill O’Reilly series with “Killing” in the title.) Killing Rommel was a WWII story about a British commando expedition during the North African campaign of ’42-’43. Kinda like The Guns of Navarone, only set in the desert, with “Rat Patrol”-type jeeps.

The story was about a raid whose aim was to kill Gen. Erwin “The Desert Fox” Rommel, the German commander of Panzerarmee Afrika.

Here’s the confession: I had been working on the book for eighteen months (seven or eight drafts) before it occurred to me, “OMG, I’d better have my commandos actually have an encounter with Rommel.”

In other words, I had left that little item out.

So, to answer your question, Shawn: “No, I don’t always plot all that stuff out in advance.”

How about in The Knowledge?

On this one, I’d say I planned it to about the 50% level. I had the interior story down cold—and most of the elements of the exterior story. I knew what “Stretch” (the character that was me) represented thematically, and Nicolette and Marvin Bablik and Peter and Marty my agent and Teaspoon my cat, sort of.

But again, the most important piece of the story eluded me.

I’m talking about the relationship between Stretch and Bablik.

This may be a pattern with me. Maybe it’s common to a lot of writers. I tend to miss the element that’s right in front of my face. It’s like a fog or a blank spot.

I was maybe three months in to writing The Knowledge when it began to dawn on me not only that a friendship was developing between Stretch and Bablik, but that this was the most important element in the book.

In that instant, Shawn, I did pull back, as you say, to the “30,000-foot view” and ask myself

What does this friendship mean?

How does it play thematically?

Is it just an accident or should I jump on this and really beef it up?

I decided that this element was happy serendipity. I lucked out. I stubbed my toe on gold.

I suddenly realized that a huge architectural element in the story was that Bablik, like Jesus, was going to take on Stretch’s sins and, by his own self-immolation, atone for them, at least partially.

Suddenly The Knowledge became a buddy story. At the center, I realized, was an unlikely pair like George and Lenny in Of Mice and Men or Ishmael and Queequeg from Moby Dick. One was going to save the other.

In other words, the narrative element originated with instinct (I was just writing scenes and letting characters talk), but then I pulled back, figured out what the element was, and deliberately went forward trying to enhance it.

I asked myself, “How can I make these guys bond with each other in a way that’s not sappy or treacly?”

Chapter 13, Bablik gets furious with Stretch for having sex with a girl in the back seat of his taxi cab. “You’re like a son to me. Stop with these skanks! Have some respect for yourself!”

Chapter 21, Stretch’s uncle warns him for the third time to stay away from Bablik. “He’s a gangster. And his brother’s worse.” But Stretch doesn’t listen. Chapter 15: “I like the guy. He’s in the shit. He’s suffering.”

Bablik cooks eggs for Stretch at his hideout in Westchester. “He cuts the omelet in half with a Case pocketknife. He gives me the big half and slides the smaller onto his own plate.”

Why did I have Stretch sleep with Bablik’s wife? Partly because it was a fun scene, but mainly to deepen the bond between them, when Bablik finds out and forgives Stretch. Bablik offers Stretch his AK-47 for protection. Stretch declines. “Too bad,” says Bablik. “You were this close to becoming a gangster.”

In the end I loaded up the story with a number of asides (and no few overt statements and acts) that showed that each one of these characters cared for the other.

More than that, I strengthened their parallel arcs. Each character was dealing with extreme guilt over a crime he had committed, which only he knew about. Each one was desperate to redeem himself. Neither one knew how.

For the entire second half of the story, Stretch is trying to save Bablik from a headlong rush to his own extinction. In other words, he’s trying to save himself.

Like I say, Shawn, I missed this parallel story completely at the start. I was months into the writing before I felt the first glimmer.

So what’s the answer to your question? I guess my method is to do both—to plan from the start as much as I can, but not too much … not so much that I don’t leave room for instinct and for happy accidents.

And when those accidents happen, I try to be alert for them and to pull back at once to 30,000 feet and ask myself the left brain/editor-type questions:

What does this accident mean?

Is it important? Is it on-theme?

Should I drop everything and focus on this alone for a while?

P.S. My favorite moment in The Knowledge comes near the end, the last words that Stretch and Marvin Bablik exchange, at the Waldorf-Astoria before Bablik heads onstage to collect his big award, after which (and he knows it) he will be killed.

“What’s your first name?” he says. “I’m sorry, I never asked.”

“Steve.”

“Steve.” He holds out his hand. “I’m Mordechai.”

That wasn’t planned.

[P.S. As this post hits the air, Shawn and I are indeed having breakfast at the Noho Star. I’m in town from LaLa Land. It’s great!]

December 23, 2016

Do This

Bruce Springsteen has a memoir out — and interviews have followed its release like B pursuing A.

During an interview for PBS’s “Newshour,” Jeffrey Brown brought up Springsteen’s voice.

Jeffrey Brown: You write about your voice. You say, about my voice, “First of all, I don’t have much of one.”

Bruce Springsteen: Yes.

Jeffrey Brown: Right? But you worked at it.

Bruce Springsteen: Initially just sounded awful, just so terribly awful, but there was nothing I could do about it. So, I just kept singing and kept singing and kept singing.

And I studied other singers, so I would learn how to phrase, and learn how to breathe. And the main thing was, I learned how to inhabit my song.

Jeffrey Brown: Which means what?

Bruce Springsteen: What you were singing about was believable and convincing, that’s the key to a great singer. A great singer has to learn how to inhabit a song. You may not be able to hit all the notes.

That’s OK. You may not have the clearest tone. You may not have the greatest range. But if you can inhabit your song, you can communicate.

Focus on that last line.

“If you can inhabit your song, you can communicate.”

Now jump to the beginning of the interview, where Brown asked Springsteen how much of him is in his songs.

Jeffrey Brown: What about that voice, though? Because in songs — I think of writers I have talked to, or poets, and there’s always the question of, how much of that is you?

Bruce Springsteen: I would say, in your memoir, it’s you.

I think that, when you’re writing your songs, there’s always a debate about whether, is that you in the song? Is it not you in the song?

Jeffrey Brown: What’s the answer?

Bruce Springsteen: So, every song has a piece of you in it, because just general regret, love. You have to basically zero in on the truth of those particular emotions.

And then you can fill it out in any character and in any circumstance that you want. If you have written really well, people will swear that it happened to you.

His answer reminded me of Steve’s recent “Use Your Real Life In Fiction” Writing Wednesdays series. Springsteen zeroes in on the real emotions — love, regret — and on the truth of those emotions he hangs lyrics that may be fiction, yet ring just as true as nonfiction.

Let’s take a quick detour to something else I read this week, “How to Build Relationships That Don’t Scale,” by John Corcoran, which closes out with “6 Tips for How You Can Build “Unscaleable” Relationships.”

The relationships the tips are focused on helping you achieve aren’t the Facebook friends who like everything you post but never buy your book. I’m talking about the neighbor who remembers your kid’s birthday every year, or the friend who buys your new books (who never asks for freebies), or the secretary at the doctor’s office who slips you in with the doc before everyone else in the cramped Friday afternoon waiting room. I’m talking about the people who have a connection with you — who like you and what you’re doing — and want to support you and your work.

Now take Corcoran’s tips and combine them with Springsteen’s advice about inhabiting and finding the truth. What you get at the end of the baking time is the one thing you need (other than a superb creation) to share your work.

You get a message that people buy into and want to share.

Look at what I’m doing here. I’m sharing Springsteen’s interview because I respect his honesty and work. I like that he tells the truth, that he shares what he’s experienced – and then there’s his work code and creativity. I’m sharing Corcoran’s post because 1) it’s good and 2) it’s on the Art of Manliness site, which I bought into years ago because I respect its founders Brett and Kate McKay.

One last stop for this thought train: James Altucher’s Facebook post “Be A Person Not A Personal Brand.”

Don’t be a book or a film or a tube of toothpaste. Focus on the person not the product.

And if you’re still trying to sort out you (as most of us are), consider trying on some of the things that made Springsteen “The Boss.” You might find that you like how they fit, too.

December 21, 2016

Detach Yourself From Everybody

(You guys, as of this post we’ll revert to the every-Wednesday mode for the remainder of the “Use Your Real Life in Fiction” series. I hope this recent barrage of Mon-Wed-Fri posts hasn’t clogged up too many friendly inboxes. I just got excited about this subject and couldn’t help myself.)

We were talking in the previous post about killing off characters. We observed that this can be hard when the characters are based on people in our real lives.

Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman in “Rain Man”

Can we kill off our best friend?

Our neighborhood priest?

Our mother?

Answer Number One:

We have to, if the drama demands it.

Answer Number Two:

We must detach ourselves emotionally from all our real-life characters.

We made the point in the last post that an old self must die before a new self can be born.

That’s why deaths (including emotional ones) are important, even mandatory, in drama.

Tom Cruise’s slick, self-centered Charlie Babbitt must give way before he can become a loving brother to Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man.

Michael Corleone’s clean-cut Marine officer must step aside before Michael-the-next-Godfather can be born.

Four of the Magnificent Seven must die before the village can be saved.

But how do you and I, as writers, kill off our own mom?

How do we destroy our own career?

Our marriage?

The answer is the most critical element in this whole series on Using Our Real Lives in Fiction.

We have to treat our real-life characters as if they were fictional.

We have to detach ourselves emotionally from the real-life version of our characters, including (especially) the character that is ourselves.

We have to free ourselves in imagination and give ourselves permission to fictionalize.

We have to see our real-life-based characters as aspects of our theme and act toward them accordingly.

If the character based on our ex-husband represents immature self-indulgence, maybe somebody has to give him a wedgie at the office Christmas party.

On the other hand, if he represents selfless integrity, maybe something really good has to happen to him. (Or bad, if it’s that kind of story.)

This is why it’s so hard to write something good based on our real life.

We’re inhibited by the material.

We’re loath to heighten its drama, to have fun with it.

We don’t want to hurt the real people we’re writing about.

All these inhibitions must be dismissed. We have to get over them.

Our loyalty must be transferred from the real-life characters (including ourselves) to the reader and to the story itself.

In a way, this is good.

It forces us to grow up.

It demands that we step back from our real-life self (and from all the real-life characters in our story) and ask, “What is this story about? What’s the deep, honest truth here?”

Can we do that?

That’s the artist’s charge when using material from her own life in fiction.

We, the readers, won’t sit still for a sob story or a self-justifying rant. We don’t want to read your diary or your journal. We want The Great Santini. We want Riding in Cars With Boys. We want To Kill A Mockingbird.

The book or movie you write will be judged as pure fiction, willy-nilly.

You’ll get no points because “this is my real story.” You will be cut no slack because “the characters are all true.”

You must make them truer than true.

You must handle your characters and scenes, no matter how real they were and are, exactly as you would if they were pure fiction.

December 19, 2016

Killing Off Characters

(Tune in to Writing Wednesdays on the next few Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays for the continuation of the series “Using Your Real Life in Fiction” — and for more of The Knowledge‘s backstory.)

We were talking in the previous post about making the stakes of our real-life story life and death.

Michael Douglas and his Gordon Gekko suspenders in Oliver Stone’s “Wall Street”

Sometimes that’s hard to do.

As writers working with our real lives as material, we can be naturally reluctant, say, to kill off a character we actually know.

Our ex-husband?

Our boss?

Our mom?

I’m sure you’re ahead of me on this. I’m about to say, “Kill ’em dead.”

Whack ’em.

Knock ’em off.

Don’t hesitate for a second.

Death is always energizing for a story. If you don’t believe me, watch Game of Thrones.

But let me expand this axiom.

Don’t be afraid to put the quietus to elements other than human beings.

A marriage can die.

A dream can expire.

A way of life can end.

Death is drama, and drama is what you and I are paid for. (Okay, maybe we’re not being paid. But you know what I mean.)

We want drama. Drama keeps our readers emotionally involved. Drama pulls them through the story. Drama delivers the meat-and-potatoes ending they’re hoping for.

Drama is change.

And no change is greater than death.

“But Steve,” you’re saying, “isn’t death a bummer? Aren’t you being dark and morbid? I want my story to be uplifting! I want a happy ending!”

I agree, I agree.

But death (the demise of a character or a dramatic component) can be an upper. Why?

Because before our hero can be reborn, she has to die.

Before Luke can become a Jedi knight, the child-Luke must expire.

Before Harry and Sally can truly share a marriage, the single-Harry and the single-Sally must be left behind.

Before France can be saved, Joan must be consumed at the stake.

Here are the deaths that happen in final third of The Knowledge:

Stretch’s marriage dies

His wife takes up with his best friend

His agent Marty expires of a heart attack

His newest friend Marvin Bablik is murdered

His book crashes and burns

Yehuda Bablik kicks him out of New York

His dream of being a novelist bites the dust

In real-life only three of these demises occurred. The other four are invented.

Why?

Because these deaths either echo, parallel, or are components of the Big Death that happens to Stretch.

He dies as an amateur.

He dies as a wannabe.

He dies as an aspirant.

These deaths are good deaths.

They are doors that close so that a brighter, better door can open.

Reading the ending of The Knowledge, we don’t know for sure what will happen with Stretch. But all signs point to him getting his act together and becoming (or at least starting to become) the professional, realized writer he has always wanted to be.

At the risk of plagiarizing from Oliver Stone’s character of Gordon “Greed is Good” Gekko from the movie Wall Street, let me suggest that, handled properly by the storyteller …

Death is good.

Don’t be afraid to use it.

December 16, 2016

Make the Stakes Life-and-Death

(Tune in to Writing Wednesdays on the next few Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays for the continuation of the series “Using Your Real Life in Fiction” — and for more of The Knowledge‘s backstory.)

Our Most Dreaded Outcome in crafting fiction based on our real lives is that the story will be too internal, too ordinary, too boring.

Jennifer Lawrence as Joy Mancuso in “Joy”

Life is internal.

Life is ordinary.

Life is boring.

And don’t forget our first axiom of the Lit Biz:

How can we make our real-life story dramatic, involving, and exciting? I’ll answer by quoting my old mentor Ernie Pintoff:

I don’t mean we have to kill off a character (though that always works,)

I mean raise the stakes.

Did you see the movie Joy, starring Jennifer Lawrence, Robert De Niro, and Bradley Cooper, written and directed by David O. Russell? The entire first half hour is about nothing but establishing the stakes for the protagonist, the real-life Joy Mancuso, as life and death. Not literally, but emotionally.

Act One introduces us to Joy as the only responsible adult in her crazy, dysfunctional extended family—all of whom are living under the same roof. We meet Joy’s bedridden mom (Virginia Madsen) , who watches soap operas all day and refuses to leave her room. Her estranged father (Robert De Niro) suddenly appears on the doorstep; he moves in to the basement, where Joy’s ex-husband is already living. Joy’s sister hates her. Joy’s boss fires her from her job. The plumbing explodes in the floor of her mom’s bedroom.

The responsibility for fixing all this comes down on Joy. She’s the designated adult. Everyone else in the family dumps their baggage on her.

Plus we see in flashbacks that the young Joy—Joy as a girl—was spontaneously and joyously creative. But that Joy has vanished under the weight of family dysfunction.

The stakes for Joy, we see, are not just life and death … they’re worse. If she can’t change the course of her life, she is doomed at the soul level. What makes the story even more powerful is the contrast between the soul-stakes for Joy and the creative flash that saves her. She invents the “Miracle Mop” and pitches it on the Home Shopping Network. What could be sillier? But the success or failure of that mop is life and death for Joy Mancuso.

I took a different tack in structuring The Knowledge.

Starting with a real-life interior narrative not too different from Joy’s, i.e. a theme of unrealized and self-sabotaged creativity … I added a second parallel story, a murder mystery that embodied this storytelling principle:

Make the internal external.

Or, put another way,

Make the invisible visible.

The aim of both techniques (that used in Joy and that employed in The Knowledge) is the same—to raise the stakes for the protagonist to life and death.

One of the ways that aspiring writers fail, when they’re using their own lives as the basis for their fiction, is they’re reluctant (often for honorable reasons) to mess too much with their truth.

They over-respect this truth.

They’re afraid if they heighten it too much, they’re being dishonest. They’re “going Hollywood.”

They’re hesitant to give their characters scenes and dialogue that the real people on whom those characters are based (including themselves) would never do or say in real life.

In The Knowledge, I had my sweet, reserved ex-wife whip out a .45 automatic and start blazing away at a carload of assassins.

I had myself beaten up, fired, rejected, cheated on, fired again, beaten up again.

I had characters die who didn’t die in real life.

Remember our other prime axiom:

Don’t be afraid to make sh*t up.

I don’t know Joy Mancuso’s real-life family. I can’t say for sure that they were (or are) as nutty and dysfunctional as the movie painted them. Maybe David O. Russell, as writer and filmmaker, was blessed with real-life characters and situations that were already over-the-top wacky.

But I doubt it.

I think David O. Russell pumped up the volume.

I think he made the internal external.

He heightened reality.

He made the stakes for Joy life-and-death.

It’s always a great exercise, when you and I read over our own stuff, to ask ourselves throughout the process:

What are the stakes for our hero?

Remember, the higher the stakes, the more emotion will be generated in the reader.

The higher the stakes, the more the reader will be sucked in.

The more she will care.

The more she will be involved in the fates of the characters.

The more she will root for the hero.

And the faster she will turn the pages.

If the stakes of your story are not life-and-death, change them.

Make them life-and-death, at least emotionally.

Don’t be afraid to make sh*t up.

December 14, 2016

Starting Your Real-Life Story

(Tune in to Writing Wednesdays on the next few Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays for the continuation of the series “Using Your Real Life in Fiction” — and for more of The Knowledge‘s backstory.)

Let’s talk about the inciting incident in The Knowledge.

Our real-life-based stories have to leave Kansas too.

It’s an interesting question because how do you identify an inciting incident in your real life? Is there a true, real-world event? Do you make it up? And if you do, how do you know what to make up?

The inciting incident in The Knowledge comes on page 29, the first page of “Book Two, The Turk.” Everything before that is set-up.

I’m following a fox fur and a pair of black leather Cossack boots.

Abigail.

Abigail Bablik crosses Eighth Avenue at 40th Street and turns up the block on the west side. I fall in, fifty yards behind her.

I’m following Marvin Bablik’s wife.

This is the job the Turk wanted to talk to me about.

The inciting incident in The Knowledge is when Stretch accepts his boss Marvin Bablik’s offer to tail his wife, ostensibly to find out if she’s cheating on him.

This incident is totally fictitious. But a tremendous amount of thought went into it. I recognized, planning ahead and structuring what was to come, that the whole story would turn on this moment. It had to be exactly right and it had come at exactly the right moment.

Let’s put this inciting incident up on the examination table and see what makes it tick.

First, why. Why is this the inciting incident? Why is this the event that officially starts the story? Because

1) With this event, our protagonist leaves the Ordinary World and enters what Blake Snyder calls the Inverted World. This is, in Joseph Campbell terms, “the Call.” In this moment Stretch embarks upon his hero’s journey. He steps out of his everyday universe and into the Extraordinary World, where all things are new and where major changes are not just possible but inevitable.

This moment is Dorothy getting swept away from Kansas; it’s Rocky learning that he’s been picked to fight the heavyweight champ; it’s Mark Watney getting left behind on Mars.

2) With this event, the internal becomes external.

Remember we said in the first post on this subject that the writer using her real life in fiction must, before all else, make the internal external?

This is that.

Stretch’s story up to this point had been entirely inside his own head. He was wrestling with issues of guilt, regret, self-doubt, self-sabotage, and self-destruction.

In other words, Snoozeville

Boring, tedious, uncinematic.

When our protagonist signs up to become an amateur gumshoe for Marvin “the Turk” Bablik however, he enters a world where vivid, butt-kicking action—car chases, beat-ups, gun fights, sex scenes, clashes with the law—are not just plausible but obligatory (even if Stretch himself is blissfully oblivious to this at the start.)

3) With this event, the genre of the story is established.

When Stretch agrees to take on this assignment, he sets the tale clearly into the Private Eye genre—and we the readers get it. We recognize that this is Jake Gittes accepting the gig to follow Hollis Mulwray. It’s the Dude saying yes to delivering the ransom money for the Big Lebowski.

4) With this event, the reader knows she can expect to see certain obligatory conventions of the genre. She knows that Bablik is lying. She’s immediately two steps ahead of Stretch. She knows that Stetch is being played for a sucker. She knows that multiple double-crosses and plot twists lie ahead. If she’s especially clever, she susses out, from this inciting incident alone, that Stretch is destined to become romantically involved with his boss’s wife whom he is tailing. Etc. Etc.

All of this sounds like fun. It’s promising. It pulls the reader forward into the story.

5) Note too that the climax of the story is embedded in the inciting incident.

We the readers may not know exactly what’s coming, but we can be pretty certain that our protagonist’s situation is going to evolve from trouble to more trouble to even more trouble.

6) Note, as well, that this inciting incident is on-theme.

The Inverted World that our protagonist now enters has not been selected randomly, nor is it designed only to carry car chases and plot twists.

Bablik’s world is a duplicate of Stretch’s.

The gangster’s universe is Stretch’s own—only made external.

Bablik—we (and Stretch) will come to learn—is also driven by guilt. He also has committed a crime for which he can never forgive himself and which can only be atoned for, in his mind, by his own extinction.

When Stretch enters this Extraordinary World, he is entering his own universe made visible and enacted, not in his mind, but in the external world.

Writers are often asked, “How much of your stories do you plot out in advance and how much just happens along the way?”

In this case, ALL OF IT was planned.

I very consciously sat down and asked myself of the inciting incident:

Does it get the story started?

Does it launch the protagonist into the Inverted World?

Does it make the internal external?

Is the climax embedded in it?

Does it establish the genre?

Is it on-theme?

I’m also asking myself, “Will this incident hook the reader? Will she get that flash-forward sense of What Is Coming? And will that pull her forward into the story?”

Are you working with material from your real life? Are you using true stuff as the basis of a piece of fiction?

Bear down, then, on the moment when the story starts.

Use a real-life event if that works.

Or make it up completely.

But, for sure, apply to that moment all the tests and criteria you would apply to an inciting incident in pure fiction.

There’s no difference.

The principles are the same.

December 12, 2016

Two Paragraphs

(Tune in to Writing Wednesdays this Wednesday for the continuation of the series “Using Your Real Life in Fiction” — and for more of The Knowledge‘s backstory.)

Two paragraphs on pages 140-141 are what The Knowledge was about for me. That was the payload. The other 273 pages are just the narrative architecture to carry what’s in those few lines.

Sometimes it’s just about the blues

Remember our earlier series on this blog called “Why I Write?” My biggest reason, at least for my early (unpublished) books, was I was writing out of pain. Pain and guilt. Pain and remorse.

I can’t prove it, but I suspect a lot of writers pound the keys for that same reason.

“Everybody commits a crime,” [Marvin Bablik says on pages 158-9 of The Knowledge.] “You, me, everybody. From that day your life becomes about nothing but dealing with that crime. How do you handle the fact that you’ve done something that can never be undone? Deny it? Seek redemption? Do you try to justify your crime? Become a criminal? Do you demand punishment? Square it with God by making sure you pay for what you’ve done? The Jewish religion is about justice. You devout? Me neither. I’m not even circumcised.”

The real-life period on which The Knowledge is based was, for me, about an unforgivable act I had committed against someone I loved. For thirty years I tried to write my way out of that.

It’s impossible of course. Words can never make up for acts. But I wanted, for myself if for no one else, to get it down on paper. To say I’m sorry. To articulate the act and the regret therefor in the hope that, like a blues song or a heartbroken poem, it might ameliorate or at least express something a reader could relate to him- or herself.

But I could never do it. I couldn’t find the vehicle. I couldn’t find the mode of expression. I just wasn’t a good enough writer.

I felt like I was carrying around one mega-concentrated drop of cyanide, and I couldn’t figure out how to discharge that drop into the landfill without poisoning somebody else in the process.

Do you remember this verse from Joni Mitchell’s “Love Or Money?”

He tried but he could not get it down

Not for truth or mystery

Not for love or money

Did something terrible happen to you?

Did you do something unforgivable to someone else?

You and I as writers are, sometimes anyway, seeking to use fiction, to employ narrative to neutralize some real-life cleavage of the heart.

The problem is we can’t just state our pain or regret straight out. It’s whiny. It’s weak. It doesn’t work.

Our novel can’t say, “Look how shamefully X treated me.” Or, “Group Y is evil; see what they did to my beloved Group Z.”

The original pain or crime must be set within a context that

1) Gives it meaning, not just to you and me as the writer, but to the reader

2) Renders it universal so that the reader can enter the experience and claim it as her own

3) Makes it beautiful.

(By “beautiful,” I mean funny if the vehicle is a comedy, scary if it’s a horror tale, sexy or romantic if it’s a love story.)

For me, in The Knowledge, I had to evolve a fictional “me,” an invented narrative, a fictional person-I-hurt, and even a slightly fictionalized crime. I had to create a parallel redemption story, involving other (fictional) characters and other fictional events. And I had to set the whole thing within a genre—in this case a Big Lebowski-type detective story—that allowed for humor, style, and aesthetic distance.

It worked.

I was able to set that single drop of cyanide within a couple of acres of peanut brittle, and when that drop came—the two paragraphs (which are still too painful for me to quote here)—it slipped seamlessly into the narrative. It fit. The puzzle turned on it.

It worked.

Do I feel better now? A little. As much as you can.

Do you, the writer, have your own two paragraphs? That is a valid reason to write. It’s an honorable reason to write. I wish you luck. I hope these posts, and your own Muse, will help you find the vehicle and the language to “get those paragraphs down.”

December 9, 2016

Pick a Genre and Run With It

(Tune in to Writing Wednesdays this Monday, Wednesday, and Friday for the continuation of the series “Using Your Real Life in Fiction” — and for more of The Knowledge‘s backstory.)

Robert Mitchum as Philip Marlowe in “Farewell, My Lovely.”

The problem with real life is it’s messy. It doesn’t fit into neat categories.

But if you and I are going to use our real lives as material for fiction, we have to do just that.

We have to wrangle it.

We have to bring it under control.

We have to pick a story category, i.e. a genre, and make our real-life narrative work within that genre.

Or put another way, we have to ask ourselves, “If this mess in our real life were a publishable, ready-for-prime-time story, what genre would that story be?”

Is our real-life tale a Love Story? That’s a genre.

Is it a Thriller? That’s another genre.

A Western?

A Coming Of Age saga?

Shawn was the one who put his finger on what The Knowledge was. He nailed it the instant I showed him the first draft. (That’s how editors are trained to think.)

It’s a private eye story. It’s The Big Lebowski. It’s a detective story where the detective is not a hard-boiled private eye but a screwed-up young writer.

I can’t tell you how much that helped me.

Why? Because every story falls into a genre and every genre has conventions [see Chapter 41 in Nobody Wants To Read Your Sh*t].

A convention is an obligatory scene. It’s a story-beat that MUST be in the narrative if it’s going to fit into the genre.

Here’s how this helped me in working out the story for The Knowledge. I thought:

Hmm. If The Knowledge is a private eye story, then I have to have at least one scene where the private eye (i.e. Stretch, the character-that’s-me) gets beaten up.

Why? Because a Private-Eye-Gets-Beaten-Up scene occurs in every Sam Spade story, every Philip Marlowe story; it happens to Jake Gittes in Chinatown; it happens to the Dude in The Big Lebowski.

I literally sat down and wrote myself this note:

Come up with beat-up scene.

What other conventions does a private eye story mandate?

If the private eye gets hired by a woman, he must become romantically involved with that woman.

Note to self:

Come up with Romantic Involvement story.

In every private eye tale, the detective gets offered a second assignment (“Find so-and-so”), usually by the person that he was hired to find in the first place.

Further note:

Come up with this one too.

If you’re following along in The Knowledge, #1 is Chapter 15, “Glen Island Casino.” #2 is Chapter 28, “University Village.” And #3 are Chapter 18, “Empire Diner.”

Does this sound like formula?

It’s not.

This is how a writer thinks.

This is how a writer works.

This is how a writer structures and shapes a story.

Remember that our Most Dreaded Outcome in attempting a story based on our real life is that the tale will be too ego-centered, too ordinary, too internal, too boring.

Our aim as writers is to

1) Heighten the drama

2) Make the internal external

3) Give the story meaning, i.e. THEME.

4) Make it universal

5) Make it beautiful

When we pick a genre and work within its conventions, we automatically accomplish all five points above (assuming we do a good job with the story).

But even better, we acquire a road map and a structure that are invaluable to us as we’re working out the fictional, and even the real-life, aspects of our tale.

Genre is not a four-letter word.

It’s our secret weapon for real-life-based fiction, and for every other kind as well.

December 7, 2016

My Cat, Teaspoon

(Tune in to Writing Wednesdays this Friday and Monday for the continuation of the series “Using Your Real Life in Fiction” — and for more of The Knowledge‘s backstory.)

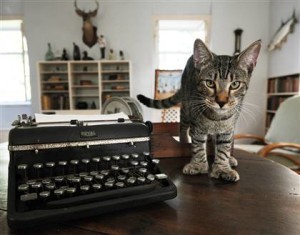

When we as writers use our real life in fiction, we tend to use real-life personalities too. One of the big ones in The Knowledge is my cat, Teaspoon.

Not the real “Teaspoon,” but pretty darn close.

My real-life cat was named Mo. I changed the name for a reason, which I’ll get into below. But first let’s flash back [see Chapter 52 in Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t] to one of the seminal principles of story-telling:

Every character must represent something greater than him- or herself.

And its corollary:

Every character must represent an aspect of the theme.

What, you may be asking, does this have to do with Steve’s cat?

The answer comes back to how a writer views material, whether that material is pure fiction, i.e. totally made-up, or borrowed from real life. In either case, the writer’s first question to him or herself is, “What does this character represent?”

Are you working on a story that has your ex-husband as a character? Your mother? Two buddies you served with in Afghanistan?

You must ask, as a writer, “What do these characters represent? What aspects of the story’s theme do they stand for?”

In The Godfather, every character represents a different aspect of the theme of family/immigrants-in-a-new-land/”criminal”-ethos-as-nobler-than-the-ethos-of-the-greater-society.

Every character in the Corleone family represents a different angle on this complex theme. Vito. Michael. Sonny. Fredo. Connie, Mama, Tom Hagen. Tessio, Clemenza, Luca Brasi.

The characters outside the family do the same. Kay represents the counter-family in terms of Mayflower WASPiness; she represents what Michael and the Corleones can never become. The gangsters in the other Five Families represent a different counter-family—criminals whose code of honor is a few levels beneath that of the Corleones.

But back to my cat, Teaspoon.

I really did have a cat during the period [see Chapter 5] in which The Knowledge takes place. I really did find him on the street as a tiny kitten; he really did travel with me all around the country; he really was an outdoor cat; he really did pad out the rear window of my apartment and down a two-flight staircase to roam around our NY neighborhood every night all night.

And my real cat really did curl up next to my typewriter as I worked, with the typewriter carriage shuttling back and forth over his head.

He would stay in that spot for hours. He became my lucky charm. As long as Teaspoon was there in his spot, I could write like a bandit. One time in California he got sick and had to stay at the vet’s for four days. I was paralyzed. I couldn’t write a word till he got back.

Did I include that last passage because it was cute? Partly. But mainly because it was on-theme.

The theme of The Knowledge is an aspiring writer must overcome his demons of Resistance, i.e., distraction, self-sabotage, and self-betrayal, before he can become a real artist.

Teaspoon represents an aspect of this theme.

He represents this struggling writer’s muse.

An animal, a creature of nature, stands for the unspoiled, instinctive connection to the Source.

I respect Teaspoon because he is his own man. I have no idea where he goes at night. He roams as far afield as Nicolette’s basement apartment, which is six city blocks away. I have no idea how he gets there. He navigates by cat radar …

He has been with me [forever] and has always been true blue. He’s the kind of cat who would lend you money, no questions asked, if he had it.

Remember our two principles regarding characters in fiction:

Every character must represent something greater than him or herself.

And

Every character must represent some aspect of the theme.

There’s another constellation of characters in The Knowledge—the gangsters Yehuda, Ponytail, and Ivanov.

They represent distraction. The self-sought-out “drama” that keeps our protagonist, Stretch, from doing his work as a writer.

Therefore, if GANGSTERS = DISTRACTION and TEASPOON = MUSE, what must happen in the story?

The gangsters have to kidnap Teaspoon.

(This was actually Shawn’s idea, after I showed him the first draft. Immediately he said, “You gotta have Yehuda kidnap Teaspoon. Teaspoon is Stretch’s muse. Stretch has gotta go all-out to recover his cat. It’s like The Big Lebowski, where the Dude is trying to get his carpet back.”)

So …

A huge part of the story became Stretch trying to get Teaspoon back from the gangsters.

Does this sound crazy? Maybe. But it works.

It works because it’s on-theme.

It works because it’s the story-in-miniature.

The reader gets it, even if only on an unconscious level.

To continue this line of thinking, let’s throw in a third element.

The character of Nicolette in The Knowledge represents a different aspect of the theme. She is, and stands for, a realized artist. She is Stretch’s semi-girlfriend, a painter who has truly found her groove and is a bona fide working, professional artist. She is in touch with her muse and in control of her artistic power.

Nicolette represents what Stretch wishes he could become.

So …

If TEASPOON = MUSE and NICOLETTE = REAL ARTIST, who winds up saving Teaspoon and giving him back to Stretch? [See page 261 in The Knowledge.]

This is the way a writer constructs a story. This is the architecture undergirding the various acts and sequences and scenes.

When you and I use our real lives as raw material for our fiction (and when we thereby recruit real people as characters), we must process these real people the same way a novelist processes purely fictional characters.

We ask ourselves, “What’s the theme? What’s our story about?”

Then: “What aspect of the theme does this character represent?”

Oh yeah, why did I change “Mo” to “Teaspoon?”

Again, to stay on-theme.

I found my cat when he was a tiny kitten, at midnight on a street called Cheyne Walk in London … The kitten was so small I could cup him in one palm and fit him into the breast pocket of my jacket. In England they call this the “teaspoon pocket.” So he became Teaspoon. I slipped him in next to my heart and he curled up and went to sleep.

Key phrase: “next to my heart.”

That’s where an artist’s muse lives.

[Don’t forget, if questions occur to you about this stuff, write ’em in in the Comments section below. I’ll do my best to answer them.]

December 5, 2016

Don’t Be Afraid to Make Sh*t Up

Oops, I lied again.

Tyrone Power and Ava Gardner in the movie version of “The Sun Also Rises”

I promised we’d get into the Seven Principles of using your real life in fiction. But again I’m gonna jump forward to a critical corollary:

Don’t be afraid to fictionalize.

I used to be. I thought if I made stuff up, that would be lying. Being untrue to real life.

I would read Henry Miller and Ernest Hemingway and think, “See, they’re telling the truth! Everything they’re writing is real! That’s why it works! That’s what I’ve gotta do!”

Of course they were fictionalizing.

They were exaggerating.

They were heightening reality.

The trick was they were doing it so skillfully, I couldn’t tell. You mean Henry Miller didn’t really do that thing with the carrot in the doorway in Brooklyn?

Even if he did, who cares?

The truth is not the truth.

Fiction is the truth.

Remember, going back to our first principle of using your real life in fiction:

Make the internal external.

Why do we as writers do this? To involve the reader. In my real life, during the era of The Knowledge, I was allowing my inner demons of guilt, regret, and self-loathing to keep me from coming together as a real working writer.

The reader is not going to sit still for that.

It’s too interior.

It’s too bornig.

The answer:

Make sh*t up.

Was I really beaten up by gangsters at three in the morning in the wetlands near Glen Island Casino? Was my boss Marvin Bablik really honored with a gala at the Waldorf-Astoria? Did my wife really fire seven shots from a nickel-plated .45 into the rear end of a vehicle loaded with Haitian assassins?

No, but all of those actions were on-theme. They all could have happened and should have happened within the invented reality of the story. And all of them are explicit statements of the parallel interior redemption narratives of the two central characters.

The rule is

You can fictionalize, but only to make the internal external.

Or put another way:

You may fictionalize only on-theme.

The Sun Also Rises is one of greatest pieces of American fiction ever. If you haven’t read it, please do. (We’ll give Hemingway a pass on his pages of anti-Semitism, homophobia, etc.)

How much of the book is “true?” My guess is 97.8%.

For sure, Hemingway hung out at the Select, the Dome, the Deux Magots. For sure he was in the First World War. For sure he traveled with friends, post-war, to Biarritz and San Sebastian and Pamplona. The bars, the bull fights, the countryside, the fishing streams, I’m sure they’re exactly as he described them in The Sun Also Rises. The Lost Generation emptiness and ennui, the hangovers, the hipper-than-thou humor, the avoidance of all topics of seriousness, the habitual drunkenness … I’m sure these are spot-on, down to the English expat slang and the details of the men’s and ladies’ wardrobe. Hemingway’s friends in the book are either real or easily-recognized composites. He probably knew someone exactly like Lady Brett Ashley and probably was in love with her and she with him.

All that is “real.” It’s all “true.”

What’s fiction?

One critical component: that the protagonist, Jake Barnes, i.e. Hemingway, had his manhood shot away in the war.

I know, I know. It’s been done before. Other characters in fiction have suffered similar emasculating wounds.

But nothing ever matched the power of that fictional incapacitation, because it told the whole story in one stroke.

That war-spawned impotence defined Hemingway’s generation as surely as “I can’t get no satisfaction” defined a later one.

What does that mean for you and me as we begin the novel that’s based on our real life?

It means

Don’t hesitate to go beyond the truth.

Identify its essence, in your character-in-the-story and in the story itself.

Then heighten that truth.

Make it pop, so that we the readers feel it and get it.

Make the internal external.

Don’t be afraid to make sh*t up.