Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 66

October 26, 2016

The Muse and Me

We were talking last week about “what works and what doesn’t,” i.e. what activities produce (for me) peace of mind at the end of the day. I listed a number that didn’t work—money, attention, family life, etc.

“It may be the devil, or it may be the Lord … but you gotta serve somebody.”

Let’s talk today about what does work.

If you asked me at this time of my life to define my identity—after cycling through many, many over the years—I would say I am a servant of the Muse.

That’s what I do.

That’s how I live my life.

[Remember, this post is Why I Write, Part 6.]

Consider this (incomplete and possibly out-of-order) selection from our newest Nobel laureate.

Bob Dylan

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

The Times They Are a-Changin’

Highway 61 Revisited

Blonde on Blonde

Bringing It All Back Home

Blood on the Tracks

Desire

John Wesley Harding

Street-legal

Nashville Skyline

Slow Train Coming

Hard Rain

Time Out of Mind

Tempest

Shadows in the Night

See the Muse in there? Mr. D might not agree with the terminology I’m employing, but he is definitely serving something, isn’t he? Something is leading him and he is following it.

That’s exactly what I do.

An idea seizes me. Gates of Fire. Bagger Vance. The Lion’s Gate. Where is this idea coming from? The unconscious? The soul? The Jungian “Self?”

My answer: the Muse.

I experience this apparition-of-the-idea as an assignment. I’m being tasked by the Muse with a mission.

You are to travel by sea to Antioch. There you will meet a tall man with one eye who will hand you a talisman ….

My instinctive reaction, always, is to reject the idea. “It’s too hard, nobody’s gonna be interested, I’m not the right person, etc.”

This of course is the voice of Resistance.

In a few days (or weeks or months) I recognize this.

I accept my task.

I accede to my mission.

This is how I live my life. From project to project, year by year. As the Plains Indians followed the herds of buffalo and the seasonal grass, I follow the Muse.

Wherever she tells me to go, I go.

Whatever she asks me to do, I do.

I fear the Muse. She has slapped me around a few times over the years. I’ve been scared straight.

She has also cared for me. She has never failed me, never been untrue to me, never led me in any direction except that which was best for me on the deepest possible level.

She has taken me to places I would never have gone without her. She has shown me parts of the world, and parts of myself, that I would never have even dreamt existed.

But let’s take this notion a little deeper.

What I’m really saying is that I believe that life exists on at least two levels. The lower level is the material plane. That’s where you and I live. The higher level is the home of the soul, the neshama, the Muse.

The higher level is a lot smarter than the lower level.

The higher level understands in a far, far deeper way.

It understands who we are.

It understands why we are here.

It understands the past and the future and our roles within both.

My job, as I understand it, is to make myself open to this higher level.

My job is to keep myself alert and receptive.

My job is to be ready, in the fullest professional sense, when the alarm bell goes off and I have to slide down the pole and jump into the fire engine.

Again, I didn’t choose this way of living.

I didn’t seek it out.

I didn’t even know it existed.

I tried everything and nothing else worked. This was the only thing I’ve found that does the job for me.

In other words, I don’t do what I do for money. I don’t do it for ego or attention or because I think it’s cool. I don’t do it because I have a message to deliver or because I want to influence my brothers and sisters in any way (other than to let them know, from my point of view anyway, that they are not alone in their struggle.)

When I say I’m a servant of the Muse I mean that literally.

The goddess has saved my life and given it meaning or, perhaps more accurately, she has allowed me to participate in the meaning she already embodies, whether I understand it or not.

Everything I do in my life is a form of getting ready for the next assignment.

October 21, 2016

Beyond the Words: Pitching Presentation and Sending

We’ve discussed pitch content in previous articles.

But what about presentation and sending? How should they look and how should they be sent?

Presentation

In his free Skillshare class, MailChimp’s Fabio Carneiro reminds viewers that research has shown “people delete ugly e-mails.” He makes a good point using design that speaks to specific types of customers, too.

“If you know your audience is mostly developers, you could make your content more technical. You could generally make your design much simpler as well, so that it’s the textual information that stands out. For designers on the other hand, they might appreciate something that looks a little nicer — and for the content to be less technical and more subjective.”

A friend in the music industry always includes a video of her clients performing whenever she shares information about them. Makes sense. The music and the performance are what’s being sold. For a visual artist, images of artist’s work make sense. Why send all text when the work is a painting?

At Black Irish Books, we’ve found the simpler the better. For promotions, keep it short, to an image, the offer, and a link. If you’re sending a newsletter, lengthy content might fly, but for pitching… Too often Steve and Black Irish Books receive pitches that run the length of short stories. The pitch — what the sender wants — is the most important piece, yet it often ends up being a short ask at the end of two pages detailing the life of the sender. On the minimalist side, there’s this:

Attached is a copy of the flyer going out to the media and public in just a couple of weeks – to promote my new book, XXX…

if would be terrific if you would/could forward it to your email list to let them know it can be pre-ordered through Amazon.com. Also – if they are interested, I will be holding special workshops in the Spring to learn how to use this xxx for xxx.

Thanks muchly — of course I will ALWAYS do the same for anything you wish to promote. Thanks.

First: We don’t know the sender.

Second: The sender’s book didn’t relate to any books written by Steve or released by Black Irish Books.

Third: No personalization. It’s the e-mail equivalent of throwing spaghetti at a wall.

*I’m not going to rip off Fabio’s full class, so go over and check it out for more on presentation. Good info. He won me over with this:

“Essentially what you’re doing in a great post is teaching others. That’s the best thing you can do, is help other people be better.”

Help other people be better.

We use MailChimp for Steve’s personal site and for Black Irish Books. I’m going through their videos now to see what I’ve missed.

Personalization

This past week, Skillshare posted a free class from Ariana Hargrave, director of VIP Services for MailChimp. Personalization is one of the items Ariana reminds viewers to target.

We’ve talked about personalization in the past. Genuine personalization — the kind that involves more than inserting a name in a merge field — is time-consuming, but worthwhile. What we’ll often do is send an e-mail to everyone on our list, and then circle back to friends, with a forward of the e-mail and a few personal notes. We don’t do it every time because we’re a small team and genuine, personalized correspondence isn’t something that can be outsourced.

Onboarding E-mails

If you’ve shopped via an online store, you’ve likely faced a pop-up, offering 10% or some other incentive for subscribing to the site. Once you sign up, you’ll receive an automated e-mail offering the promised gift.

This is important: This is your first e-mail to new subscribers.

Make a good impression.

With the digital download or coupon code, or whatever it is you’re offering, consider providing a special unannounced bonus or a special video about your work, your company’s mission, and so on — and make sure you say THANK YOU.

Abandoned Cart Messa g e

This is the e-mail you receive when you don’t complete a purchase. You went as far as putting a product in a shopping cart and then an important call came in, you had to send a file to a client, the kids came home and you had to get dinner, and then by the end of the day you forgot — or you simply changed your mind once you saw the shipping cost and bailed.

These are particularly good for limited time/limited quantity offers. After almost every promo we’ve done, we’ve received e-mails from customers that started their purchases and then …. “Something came up. Can you squeeze me in? Can I still receive the promo?” Same for customers that thought they made a purchase, but somehow it “didn’t go through.”

Purchase Follow-U p

If you’ve ever bought something on Amazon, you’re familiar with the e-mails that arrive within a week of you receiving your purchase. These are call-to-action e-mails, requesting that you share a review about your purchase.

As with the onboarding e-mails, purchase follow-up e-mails can be used to provide a bonus, too. Maybe you send a short story surprise, a cartoon, or a short how-to video with your thank you.

Timin g

The timing of messages is the piece of Arianna’s video that had me taking notes.

We’ve always sent e-mails out at the same time, which means 9 AM on the East Coast, 6 AM on the West Coast, and later for international. MailChimp allows for staggered sends, “Time Warp” e-mails, so we could send e-mails out at 9 AM whenever 9 AM hits different locations, rather than at one time. This way, e-mails would hit at 9 AM on the East Coast, at 9 AM on the West Coast, at 9 AM in London, and so on… Optimize the timing for different locations.

With onboarding e-mails, strike while the iron’s hot. Set the auto e-mail for an immediate send upon subscription.

For abandoned carts, give it some time — and don’t go overboard. A gentle reminder within 24 hours is great, but… You’ll run subscribers off if the e-mails don’t stop.

For purchase follow-up, give it at least a week. Sending an e-mail request for a review five minutes after a print copy was purchased doesn’t make sense. The book hasn’t been sent, so it hasn’t been received, which means it hasn’t been read. By the time the reading portion hits, your e-mail will be forgotten and likely deleted.

Best Customers E-mail

This isn’t something I’d thought about until Ariana brought it up in her video. We have a number of college stores that purchase Black Irish Books’ titles every semester. Every semester, the stores order at the last minute and then want everything rushed. With these routine customers, we could be timing e-mails, sent only to them, at the beginning of each semester, nudging them to submit their orders. Although Black Irish Books wasn’t set up to sell into the school stores, that’s exactly what’s happening. Makes sense to target them on the front end, instead of rushing on the late end. The same can be done with other repeat buyers. If we look at order history, we can identify ordering trends for repeat customers. Makes sense to touch base with them.

MailChimp isn’t the only e-mail system available, but it is the one we’ve used. Whether you use it or not, definitely check out their videos on Skillshare. They are free — and you’ll likely find more to explore on Skillshare, too.

October 19, 2016

What Works and What Doesn’t

I declared in the second Why I Write post that I would have to kill myself if I couldn’t write. That wasn’t hyperbole.

Henry Miller

Here in no particular order are the activities and aspirations that don’t work for me (and I’ve tried them all extensively, as I imagine you may have too if you’re reading this blog):

Money doesn’t work. Success. Family life, domestic bliss, service to country, dedication to a cause however selfless or noble. None of these works for me.

Identity-association of every kind (religious, political, cultural, national) is meaningless to me. Sex provides no lasting relief. Nor do the ready forms of self-distraction—drugs and alcohol, travel, life on the web. Style doesn’t work, though I agree it’s pretty cool. Reading used to help and still does on occasion. Art indeed, but only up to a point.

It doesn’t work for me to teach or to labor selflessly for others. I can’t be a farmer or drive a truck. I’ve tried. My friend Jeff jokingly claims that his goal is world domination. That wouldn’t work for me either. I can’t find peace of mind as a warrior or an athlete or by leading an organization. Fame means nothing. Attention and praise are nice but hollow. “Wimbledon,” as Chris Evert once said, “lasts about an hour.”

Meditation and spiritual practice, however much I admire the path and those who follow it, don’t work for me.

The only thing that allows me to sit quietly in the evening is the completion of a worthy day’s work. What work? The labor of entering my imagination and trying to come back out with something that is worthy both of my own time and effort and of the time and effort of my brothers and sisters to read it or watch it or listen to it.

That’s my drug. That’s what keeps me sane.

I’m not saying this way of life is wholesome or balanced. It isn’t. It’s certainly not “normal.” By no means would I recommend it as a course to emulate.

Nor did I choose this path for myself, either consciously or deliberately. I came to it at the end of a long dark tunnel and then only as the last recourse, the thing I’d been avoiding all my life.

When I see people, friends even, destroy their lives with pills or booze or domestic violence or any of the thousand ways a person can face-plant himself or herself into non-existence, I feel nothing but compassion. I understand how hard the road is, and how lightless. I’m a whisker away from hitting that ditch myself.

The Muse saved me. I offer thanks to the goddess every day for beating the hell out of me until I finally heeded and took up her cause.

No one will ever say it better than Henry Miller did in Tropic of Capricorn.

I reached out for something to attach myself to—and I found nothing. But in reaching out, in the effort to grasp, to attach myself, left high and dry as I was, I nevertheless found something I had not looked for—myself. I found that what I had desired all my life was not to live—if what others are doing is called living—but to express myself. I realized that I had never had the least interest in living, but only in this which I am doing now, something which is parallel to life, of it at the same time, and beyond it. What is true interests me scarcely at all, nor even what is real; only that interests me which I imagine to be, that which I had stifled every day in order to live.

October 14, 2016

Why Love Rules

Lenny Kravitz Launched His Career with Love Story

What if tomorrow everything you’ve learned about storytelling disappeared?

What would you do?

Where would you begin to relearn your craft?

For those of us who spend a considerable amount of our conscious hours inside our heads, the likelihood of this happening is pretty slim. Barring some highly unlikely blunt force trauma to our noggins, we’re not going to lose everything we know overnight.

But is it not instructive to use our imaginations to consider what we would do if the worst catastrophic fantasy of a storyteller were to actually happen?

For anyone who has played competitive sports, this idea of having to start all over again is not exceptional. And the longer you played, the more likely it was to occur.

The football player or soccer player who blows out an Anterior Cruciate Ligament on the field on Friday, Saturday or Sunday game faces surgery on Monday. And that unnerving and ethereal experience is soon followed by one of the most painful words in the English language…. Rehab.

Rehab is a process of managing pain in the service of regaining fundamental skills. It doesn’t just require an acceptance of intense discomfort (my old physical therapist’s softer phrase for torture), it requires the abandonment of a taken for granted reliance on previous mastery.

You literally have to relearn how to stand up before you’ll be able to walk. You have to relearn how to walk before you can jog. And jog before you can run in a straight line. And then you have to relearn how to best change directions (that’s when the real pain begins when you’re 90% back to form)…and what muscles must be rebuilt to accomplish those changes.

It’s a humbling process, but it’s not a baffling series of steps.

You simply do what you need to do to stand. Do what you need to do to walk. Do what you need to do to jog. Do what you need to do to run. Do what you need to do to cut. Repeat. Those are the five stages of rebuilding a knee.

Which begs the question…

What would be the equivalent series of intellectual steps to learn or refresh our understanding of storytelling?

What must we do to “stand” as storytellers?

Good old Marcus Aurelius’s recommendation that we peel back the onion layers of a skill and “Of each particular thing ask: what is it in itself? What is its nature?” is a good place to start.

All of those who’ve read anything I’ve written about story structure will not be surprised by my go-to starting point to figure out what story is in itself…

I’m going to begin by looking at Genre.

And what I mean by Genre is simply the way by which we divide or classify kinds of stories. What kinds of boxes we put them in.

There are a lot of Genres. Check out my five-leaf clover definition of Genre here and you’ll soon want to run for the hills.

But before you do, let’s take a step back and ask ourselves a simple question…did all of those Genres come from some primal place?

Was there some fundamental want or need that human beings desired or required to survive a hostile environment? And could that want or need be fulfilled by simply following the behavioral prescriptions inherent in a compelling story?

What I mean by “behavioral prescriptions” isn’t as complicated as the phrase may seem. Just think of asking someone or some artificial intelligence for directions.

What do they do? They tell you a story. You start here, turn there, turn there, look for the gas station on the left, turn right and you’ll get where you need to be. Those are behavioral prescriptions that derive from a third party narrative…How to change your behavior to get to the place you want to be.

So what was the first story?

Obviously Action stories were probably first. They concern overcoming an external life threatening force, like hunting prey or avoiding a pack of hungry wolves or something. The stakes are huge and ancient cave drawings prove how important these stories were to our loincloth-clad forebears. Getting our water, food and shelter are mucho importante. And the behavioral prescriptions to get those things are crucial to our day-by-day survival.

And War stories were primal too. They lent direction when human forces intent on our destruction marched into our private valley. So stories about how to outmaneuver and survive an invasion sit alongside environmental Action stories as a primary genre.

But wait, let’s back up even more…is there a need within us all that is even more fundamental than water, food, and shelter?

There is.

It’s love.

Without love, we’re dead.

If mom doesn’t love us enough to take care of us as infants, we die. Simple fact.

None of us can make it alone. Not even Donald J. Trump.

When the state wants to destroy a person, they put them in solitary confinement. Sentenced to 365/24/7 with only our internal voices is torture. It’s just not better to connect with others…it’s life-saving.

Love is the force that not just binds us to the rest of humanity…it’s the very thing that preserves our species. To fail to love therefore is not only an external threat to our own private lives; a love breakdown across humanity will take down our entire life form.

So, sure the short-term primal genres (Action, Horror, War, Thriller) concern the concrete foundation of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs…how to survive today.

But the Love Story is the long-term mother of all Genres. It’s not just about how to survive today; it’s about how to last a lifetime…and even how to gain a measure of immortality. Good old Marcus Aurelius has a measure of immortality, doesn’t he? His work still resonates today…probably far more than it did in his own lifetime.

Love story is the structure that instructs us on how to discover the meaning of our existence. Both as individuals and as atomic particles that bump in to one another in a complex action and reaction that comprises the human collective unconscious. Don’t forget that Marcus Aurelius is still bumping around in that soup today even though he left earth 1,836 years ago…and we think Cal Ripken’s Ironman streak is something…

So if we want to refresh our storytelling craft, what better Genre is there to examine than the Love Story?

In the next series of posts, I’ll open up the hood of the internal combustion Love Story engine and see what makes that baby purr.

October 12, 2016

Writing “As If”

Jerry Garcia. “Dude, ‘as if’ works!”

The hippie version of behavioral therapy (I remember it well) was “acting as if.”

Are you scared? Are you anxious? Act as if you’re not.

Shawn has a principle for Black Irish Books: publish as if. In other words, bring out a book/promote it etc. as if we were Knopf, as if we were Random House.

What about writing as if?

(Remember, the theme of this series is “Why I Write.” It’s my own admittedly personal, idiosyncratic, possibly demented view of why I do what I do.)

I definitely write as if.

I write as if I’m being published by Penguin Random House/Simon&Schuster/Hachette/HarperCollins.

I write as if my stuff is gonna be reviewed by the NY Times, the New Yorker, the Times of London.

I write as if the Nobel Prize committee will check every comma.

I write as if Steven Spielberg will be personally eyeballing an advance reading copy.

I write as if people will be reading my work five hundred years from now (assuming of course that planet Earth is still habitable by humans at that time.)

More critical than all the above, I write as if the Muse herself will be going over my stuff. I don’t want her saying, “I gave you this?”

But let’s take this line of thinking to a deeper level.

You and I as writers must write as if we were highly paid, even though we may not be.

We must write as if we were top-shelf literary professionals, even though we may not (yet) be.

We must write as if we were being held to the highest standards of truth, of vision, of scale, of imagination, even though we may not be.

We must write as if our works mattered, even though they may not.

As if they will make a difference, even though they may not.

As if our lives and sanity depend on it. Because, believe me, they do.

To say that we write (or live) “as if” is another way of saying we have turned pro.

We are operating as professionals.

We are in this for keeps.

We are in it for the long haul.

We are committed.

We are warriors.

We are for real.

Therefore … take no thought how or what ye shall speak; for it shall be given you in that same hour what ye shall speak.

There is great wisdom in acting as if and writing as if.

Is life without meaning? Are you and I marooned on an atom of dust hurtling in the dark through a pointless cosmos?

Maybe.

But we can’t act as if we believed that.

Art Carney and Lily Tomlin in “The Late Show”

We must act as if there were meaning, as if our lives and actions did have significance, as if love is real and death is an illusion, as if the future will be better than the past, whatever that means.

One of Seth Godin’s great contributions is the idea of “picking yourself.” Don’t sit on a stool at Schwab’s like Lana Turner waiting for someone else to pick you to be the next star.

Pick yourself.

Act as if you were a pro, a fastball hitter, the real thing,

And there’s additional magic to the practice of acting as if and writing as if. In some crazy way, acting and writing as if makes our beliefs about ourselves come true.

What we had only projected takes on its own reality. That’s a law.

“You’re an actress,” Art Carney tells Lily Tomlin at a scary moment in Robert Benton’s great private eye flick The Late Show. “Act brave.”

October 7, 2016

You Need More Than A High IQ

“ Knowing how something originated often is the best clue to how it works.”

— Terrence Deacon

The good news: IQ levels are higher today than they were 100 years ago—and continue to increase.

The bad news: Higher IQs aren’t making us smarter.

In a recent interview with the BBC, James Flynn said, “the major intellectual thing that disturbs me is that young people . . . are reading less history and less serious novels than [they] used to.”

From Flynn’s perspective, this lack of reading makes us ripe for an Orwellian dystopia. “All you need are ‘ahistorical’ people who then live in the bubble of the present, and by fashioning that bubble the government and the media can do anything they want with them.”

He’s right. George Santanaya wasn’t joking when he said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Then there’s this quote, also from that BBC interview:

“Reading literature and reading history is the only thing that’s going to capitalise on the IQ gains of the 20th Century and make them politically relevant.”

Let’s take politics out of it and focus in on the individual.

Even at the very basic level, as in considering your personal career goals, being “ahistorical” is a recipe for disaster.

As we’ve spent more time on this site discussing the development and sharing of creative work, emails have continued to stream in from individuals, requesting Steve mentor them, that Steve take a look at their project, that Steve introduce them to people who can help them, that Steve tell them how to fix their personal lives, and so on . . .

I used to blame Laziness for these emails. While Laziness ain’t completely off the hook, Rational Ignorance is the better hook on which to hang their cluelessness.

Just as I haven’t learned how to fix my washing machine, because the investment of time and money spent learning how to fix my washing machine outweighs simply paying a specialist to fix it, individuals e-mailing Steve think that the investment of time and money spent learning their desired trade outweighs the effort to simply ask Steve for help.

These individuals don’t realize that they’re screwing themselves. Rather than asking someone else the answer to 892 + 1297, or using a calculator to figure it out, they’d benefit from knowing how to do simple addition themselves.

And, if they continue to resist learning how to do something themselves, the answers to most of their questions are already out there.

We live in the age of information. “Content” is flying at us from all direction. The answers are on the record.

And yet…

The e-mails keep coming in.

Back to Flynn.

During the BBC interview, it sounds like Flynn gave the interviewer grief for not knowing about the Thirty Years War.

I’m not taking it that far.

I’m keeping it basic.

Start with your own life.

Stop e-mailing and asking others for an “in.”

Understand the history.

Know the players.

Master the business.

Do the work yourself.

Tomorrow you can hit the Thirty Years War.

October 5, 2016

What Kind of Writer Are You?

“Jim’s looking for something edgy, something David Fincher-esque.”

I had been working in Hollywood for five or six years and had a semi-respectable B-level screenwriting career going, when I got a new agent. My new agent was a go-getter. He decided to mount a campaign where he would “re-introduce me to the town.” That sounded good to me. I said, “Let’s do it.”

My new agent started setting me up with meetings. The campaign would last six weeks, he said. He would send me out to two or three places a week—studios, production companies, the individual development entities of actors, directors, etc.

The meetings would usually last between half an hour and an hour. They were meet-and-greets, friendly, informal. It would be me and two or three development execs. The company people would tell me what they were looking for and I would tell them what I was working on. For example, if it was the production company of an actor, the execs might say, “Jim’s looking for something darker than his usual stuff, something David Fincher-esque, with a real edge to it.” Or I might say, “I just finished a spec Western” or pitch them a supernatural thriller I had percolating inside me.

The hope was that the twain would meet and a gig would come out of it, or maybe I would sell one of my specs. And for the first couple of weeks, everything was going great. The meetings had energy; plans were made; I was doing callbacks and follow-ups.

The only problem was I getting depressed.

I mean down.

Clinically down.

Three weeks became four. My tally was up around ten, twelve meetings.

I was getting seriously bummed and I couldn’t figure out why.

I got to dreading these meetings.

What was wrong with me?

Why was this experience such a bringdown?

My bummed state seemed to make no sense. The people I was meeting and working with were universally smart, dedicated, enthusiastic. They knew movies. They liked me.

What was my problem?

Slowly the answer began to dawn on me.

Floating in the air in every meeting was an unspoken assumption. Everyone in the room bought into this assumption. This assumption was the foundation of everything the studio and development people said and did.

It was assumed that I, by virtue of being in these meetings, accepted this assumption too.

The assumption was this:

We will do anything for a hit.

The goal was box office. A winner at any cost. Short of producing a snuff flick, the name of the game was commercial success.

Who could argue with that, right?

Hollywood is a business. That’s why they call it “the industry.”

The problem was I didn’t accept that assumption. It wasn’t my assumption. I didn’t buy into it at all.

I wanted to write what I wanted to write. What I cared about was whatever idea seized my imagination. I wanted to have a hit, sure, but out of 100 potential writing ideas, there were at least eighty I wouldn’t touch, no matter how much you paid me or how sure-fire they were at resulting in a hit. They just weren’t interesting to me.

It struck me that I might be in career trouble.

I was actually getting kinda scared.

I realized that I wasn’t in the same business as the executives I was meeting with.

They were looking for one thing and I was looking for another.

In other words, for the first time in my twenty-plus year writing life, I found myself confronting the questions, “What kind of writer am I? Why am I doing this? How do I define success as a writer?”

Am I a writer for hire?

Am I a genre writer?

What kind of writer am I?

And more important: Am I in the right business? Is there a future for me here?

OMG, am I facing a career crisis? At forty-three years old am I gonna have to reinvent myself yet again? As what?

Here was the conceptual breakthrough that solved the problem for me (at least for the moment):

I visualized two circles.

One circle was “Movie ideas that the industry wants to make.”

The other was “Movie ideas that I want to write.”

The two circles might not coincide, one on top of the other. They might in fact barely overlap at all. But there was some overlap, however marginal or occult.

I told myself, “I will make my living in that overlap.”

And it worked.

For another five or six years, for six or seven screenplays (most unproduced but all written to a paycheck), this new theory worked fine.

The problem was I had opened a Pandora’s box by asking those questions, “What kind of writer am I? What is my objective? How do I define writerly success for myself?”

The answers eventually carried me out of the movie biz.

What kind of writer are you?

Why are you pursuing a literary vocation?

How would you define success for yourself?

These are questions that we have to ask and answer, you and I, no matter how uncomfortable they make us or how much we’d prefer to avoid them entirely. For me, the process was life-altering and life-enhancing. These questions and the answers they elicited helped me not only to advance along the path I had embarked on, years earlier, blindly and impulsively, but also to see that path clearly and to understand it (or begin to understand it) truly for the first time.

We’ll keep investigating these issues in the coming weeks.

September 30, 2016

How NOT to Tell a Story

I’m re-running an article I wrote fifteen months ago about a full page advertisement in The New York Times.

The reason why is this article from Bloomberg Businessweek, How Hampton Creek Sold Silicon Valley on a Fake-Mayo Miracle, that ran on September 22, 2016. It details the company’s buy-back campaigns to artificially inflate its popularity and short term financial success.

Essentially the company funded a wide net of dedicated followers (coined “Creekers” who took the do-gooder positioning of the company at face value) to go into grocery stores and buy its products so that it could use industry trusted data to influence its appeal to investors. The Creekers emptied the shelves of Hampton Creeks’ “Just Mayo” at Whole Foods which induced Whole Foods to report vibrant sales data and re-order. “Just Mayo” was soon the #1 selling mayonnaise at the chain.

My read from the Businessweek investigation is that the primary purpose of the Hampton Creek is to attract marquee investors to fund it to a billion dollar valuation. That valuation would pose such a threat to one of the major food conglomerates (Unilever in particular which owns Hellman’s Mayonnaise) that it could induce them to acquire the company at an inflated value.

If the Businessweek piece proves correct, this buy back approach is even more cynical and unethical than those who pay third parties to go to bookstores and buy up their books so that they’ll hit bestseller lists. And that’s saying something.

All of this chicanery aside…what’s important for us as writers and entrepreneurs etc. is to remember that having a comprehensive understanding of story structure is not just helpful for us as creators.

It’s an indispensable analytical tool to save us from charlatans.

When we understand story structure we are empowered to see through the hype and directly question the motivations of the messenger. Here’s the post again to walk you through why this advertisement set off my story alarms.

A full page advertisement on Page 7 of the Sunday June 21, 2015 edition of The New York Times—in the main news section a full page requires 126 column inches at a retail price of $1,230 per inch ($154,980)—ran as follows:

Inanity as Philosophy

Dear Food Leaders,

I’ve had lots of successful folks give me advice about you. Advice on whether to work with you (be wary), on how to grow with you (go slow)—and the good we can do with you (very little).

We built a movement, and the fastest-growing food company on earth, around intentionally ignoring all of it.

We started Hampton Creek because we believe in the goodness of people—in the goodness of you. And you, the same folks who created a food system that often violates your own values, have validated what all of us knew: It turns out that when you create a path that makes it easy for good people to do good things—they will do it.

I know we’re all buried in the to-do list of the day. But you should know, that as of 5:33 AM EST on Sunday June 21st, our movement includes:

The largest food service company in the world

The largest convenience store in the world

The two largest retailers in the world

The second largest retailer in the US

The largest natural grocery retailer in the world

The largest grocery retailer in the US

The largest retailer in the UK

The largest grocery retailer in Hong Kong

The largest coffeehouse in the world

Two of the top ten largest food manufacturers in the world

Two of the World’s 100 Most Powerful Women (Forbes)

The sovereign wealth fund of Singapore

A former Republican Senate Majority Leader

The world’s leading virologist

The Co-founder of Facebook

A Medal of Honor recipient

The leading experts in machine learning

The Godfather of hip-hop

4,121 public schools

12 billionaires

And many of your kids

Just three years ago when we started, I thought you were the problem. And I was wrong. You have always been the kinds of folks who know what the right thing to do is. You have names. And families. And you, just like all of us, want your kids and friends and loved ones to admire who you are. And you, just like all of us, are just trying to figure it all out.

Did you know that our manifesto was written by you?

And that our 2015 impact is driven by you?

1.5 billion gallons of water saved

11.8 billion milligrams of sodium avoided

2.8 billion milligrams of cholesterol removed

You should feel insanely proud.

Talk soon,

Josh Tetrick, CEO & Founder

PS: You can reach me anytime at (415) 404-2372 or jtetrick@hamptoncreek.com

First of all, I read this advertisement because I’m interested in the food industry. I’ll spare you my thoughts about big agriculture and of processed edibles and instead just cast my jaundiced editorial eye upon the literal text above.

But before I do, I also need to point out that I do not know Josh Tetrick. And my criticisms of the words that make up his advertisement and my references to “the letter writer” are in no way a commentary on him as a human being or his company. I simply have no opinion of the man or the work he does. I don’t know enough to make a judgment. I only have the words in this advertisement that appear above his name.

Because I write and publish my work publicly here and at www.storygrid.com, I understand that my words are fair game for third party criticism. I know the sting of others ridiculing something I’ve written and it’s, to say the least, unpleasant. So in the past I’ve taken the approach that it’s better to praise the masterpieces of story than to criticize those wonderfully flawed works of artists in training (the rest of us struggling to get better). I prefer to praise than to condemn hardworking artisans.

And I’ll continue to take that tack when I storygrid future works of fiction and nonfiction. I’m currently in the throes of storygridding Malcolm Gladwell’s seminal work of Big Idea Nonfiction, The Tipping Point, a process that’s teaching me a boatload about the power of an idea.

But when I’m presented with a block of text the purpose of which is to induce me to purchase a product or sign on to support something (an advertisement), I have no problem pulling on the critical boxing gloves.

I hope that my admittedly severe nitpicking below can teach something about the importance of Story. And of how telling a Story poorly is far worse than not telling the Story at all.

Let’s begin with the format of this advertisement.

Why would a food company’s CEO use the epistolary style genre to tell his and his company’s Story? For an explanation of my big picture Genre theory, click here.

The company Hampton Creek…from what I understand after doing some searching…produces an egg-like substance from plant material and uses it to create two retail products, Just Mayo (a mayonnaise substitute) and Just Cookies.

What it makes and even how it makes it isn’t exactly the stuff of narrative drive. How do you get around that?

One way is to share a heartfelt letter. Because letters connote intimacy.

This is why we keep the old love letter from our first girlfriend tucked into our high school copy of The Catcher in the Rye. Letters make us feel connected. They provide comfort or… proof. Proof of love, of betrayal, etc.

There is a reason why every civil lawsuit begins with the discovery process. All letters and emails etc. must be turned over to the court so that the “truth” can be parsed from the trail of intimate conversations of the parties involved. The understanding is that letters and emails reveal the authentic feelings of their authors.

We have an expectation of sincerity and truth, at least the writer’s version of the truth, when we sit down, open and read a letter.

So when a storyteller chooses to tell his story with a letter, he’s taking advantage of a powerful genre, one that immediately pulls the reader in for an intimate experience. The reader has the expectation from the very first word that the writer of the letter is going to “open the Kimono” of their true self.

Once the storyteller has chosen the epistolary style, his next choice is who to address the letter to.

He can address the letter to a single known reader or a global group of known readers. “Dear Shawn,” or “Dear People of Earth,” for example.

He can address an unknown single reader or a group of unknown readers. “To Whom it May Concern,” for example.

He can address a specific group or organization or corporation and share the open letter with the public as a means to affect a very specific, time sensitive change in the behavior of that group. An example would be the “Authors United” letter criticizing Amazon.com in their dispute with the Hachette Publishing Group in August 2014.

Now for anyone who’s followed my stuff, you’ll know that I’m always looking for the inherent structure of a Story. I want to figure out the Beginning Hook, Middle Build and Ending Payoff. Because these three parts are indispensable in a story, no matter the length.

The addressee is the Beginning Hook part of the epistolary story.

Remember, a well-told story is like a joke. It promises a specific type of payoff (a specific kind of laugh) with its beginning hook. And after the progressive complications of the middle build, it pays off that hook in an unexpected, but inevitable way (a bigger laugh than we anticipated).

Let’s go to the text of the ad:

Josh Tetrick’s letter begins “Dear Food Leaders,” which is choice Number 3 from above. And the Number 3 variety’s beginning hook implies a “call to action” payoff. That’s the obligatory element. What that means is that we as readers subconsciously expect the letter to end with the writer asking something of the addressee or of us. Or both the addressee and the reader.

The Authors United letter wanted the readers of the 900 writers who signed the document to email Jeff Bezos and ask him to settle Amazon’s dispute with Hachette. Obviously, the 900 writers didn’t expect the general public to check to make sure that they’d read one of the books those writers wrote before considering the call to action.

They used their impressive group number to influence anyone interested in the writing life to email Jeff Bezos. Publishing the letter in The New York Times made sense because chances are that people who read the newspaper also read books.

Now, when I first saw the “Dear Food Leaders” ad in the paper last Sunday, I was hooked. I like these kinds of letters/stories.

I’m interested in what agricultural insiders have to say to “Food Leaders.” If Joel Salatin shared a letter with readers of The New York Times that began “Dear Food Leaders,” I’d know that he would pay off the letter by calling for action from them or directly from me the reader. And I’d want to know what that action was.

Plus I know that a full-page ad costs a lot of money, so the fact that it’s in the paper means that whatever this ad says is really important to the person who signed it.

So I’m willing to give this unknown author my attention just with that opening. That’s the hook.

I’m thinking that the author is obviously going to fill me in on who these “Food Leaders” are, right? Just as the Authors United clearly identified Amazon.com and Hachette and its major imprints in the very first sentence of their letter.

But no, instead the author leads with this:

“I’ve had lots of successful folks give me advice about you.”

As difficult as it is for me, I’ll let the letter’s deliberate homespun colloquial tone slide for now.

Sorry, I thought I could, but I can’t let it go without comment.

The use of the word “folks” smacks of such an obvious attempt of the letter writer to make himself come off as just an “aw-shucks ordinary Joe” that my immediate reaction is “this writer is full of BS…he’s playing a game…don’t believe a word of what he writes.”

Seriously, the very first sentence alienated me. And while I’m unique, I don’t think I’m the only one who finds that kind of forced “simple talk” grating.

What’s even worse is that there is absolutely no transparency about what the letter writer wants or what he was even looking for in the past that solicited advice.

“I’ve had” is a Present Perfect verb tense. You use it to refer to an experience or action that happened at some time in the past, when the specificity of time is not important. “I’ve had benign mosquito bites,” is an example of an appropriate use of the Present Perfect.

And just who are these “successful folks” who gave the letter writer advice at some unspecified time in the past? Specifically? Are they Warren Buffett? Jimmy Buffett? Kanye West? Adam West? Who gave the advice?

We never find out. Which begs the question: Why isn’t the letter writer telling us?

And, who is “you,” the Food Leaders? Monsanto? Sysco? Aramark? US Foods? Tyson?

We never find out. Which begs another question: Why isn’t the letter writer telling us?

Who is “I?” for that matter? I don’t know the writer of this letter. Why is he assuming I care about what some nameless successful folks have told him about some nameless Food Leaders?

What the Hell is going on?

I can only infer that the letter writer is someone who works in the “Food” world wishing to get something from its “Leaders.” He’s making his statement public (at great expense) in order to convince someone like me “not in the Food World, just a reader of the The New York Times” that what he wants from these Food Leaders is worthy of some action on my part.

I’m completely on guard now. But I’m still curious what his “ask” of me will be. So I read on.

The letter writer then talks about the subjects of the advice that he received from the nameless successful folks. Whether he should work with unnamed Food Leaders. How he can “grow” with unnamed Food Leaders. And lastly what “good” “we” can do with unnamed Food Leaders.

Now, the letter writer has shifted from first person singular “I” to the first person plural “we” without ever telling us who he is or who he represents as part of this new “we.”

It’s been my experience that writers change the point of view so suddenly from “I” to “we” to hide inside a group.

Hey, it’s not just me…it’s a whole group of “us” who think this way.

This First Person Singular to First Person Plural mid-stream shift is a way of protecting the writer from opposing views by warning the critical reader that there are a whole slew of others (again unnamed) that stand behind the writer’s previous and future statements. It’s a preemptive strike against dissent.

And it ain’t a good idea. It reminds me of schoolyard playgrounds when some loud mouth takes it upon himself to tell another kid that everyone else wants him to scram…

Here’s a bit of advice. If you are the only signatory to a letter, write in First Person Singular. If a whole group of people signs a document you’ve written, use First Person Plural.

The subtext for me from this early mess of sentences is that the writer is trying to tell me that he is in possession of such a remarkable product or idea that “Food Leaders” long to be in business with him. He is also in a social circle of smart and rich folks in the same arena who have advised him not to rush into business with these anxious door-knocking Food Leaders. The reasons given why he shouldn’t quickly align with these Food Leaders are mysterious. Why be specific now?

The next sentence is even worse.

“We built a movement, and the fastest-growing food company on earth, around intentionally ignoring all of it.”

HELP!

Who is “We?” What “movement?” What’s with this crazy hyperbole, “the fastest-growing food company on earth?” Why would you, sorry “we,” ignore the advice of “successful folks” so cavalierly?

Oh, okay, in the next sentence comes the explanation of what the Hampton Creek movement is all about:

“…we believe in the goodness of people—in the goodness of you.”

WOW! They believe in the goodness of people! And in the goodness of Food Leaders too!

Of such pandering inanity are pseudo egg dreams made.

This reminds me of the motto of fictional Faber College in Animal House: KNOWLEDGE IS GOOD.

The rest of this letter/advertisement is so opaque and loaded with false modesty and treacly sentiment that if I hadn’t gone online to research the company, I’d have thought it was a gag ad written by someone like John Cleese.

Needless to say, there never is a call to action. The hook doesn’t pay off. There is no middle build. It’s not a Story. I’m not sure what it is.

One last thing that really strikes me as just crazy Chutzpahdik is the cynical attempt to lodge the letter writer in our minds alongside the modern era’s patron saint of irrepressible entrepreneurship (Steve Jobs).

Here is the last sentence before the letter writer’s saccharine sign off of “Talk soon”

“You should feel insanely proud.” (Italics mine)

What this ad represents is nothing to be proud about. It’s an insanely great example of how not to tell a Story.

[Join www.storygrid.com to read more of Shawn’s Stuff]

September 28, 2016

Why I Write, Part Two

If you’re a writer struggling to get published (or published again) or wrestling with the utility or non-utility of self-publishing, you may log onto this blog and think, Oh, Pressfield’s got it made; he’s had real-world success; he’s a brand.

J.K. Rowling has earned her spot on the Elite List

Trust me, it ain’t necessarily so.

I don’t expect to be reviewed by the New York Times. Ever. The last time was 1998 for Gates of Fire. That’s eighteen years ago. The War of Art was never reviewed, The Lion’s Gate never. My other seven novels? Never.

I’ve got a new one, The Knowledge, coming in a month or two. It will be reviewed, I’m certain, by no one.

If I want to retain my sanity, I have to banish such expectations from my thinking. I cannot permit my professional or artistic self-conception to be dependent on external validation, at least not of the “mainstream recognition” variety. It’s not gonna happen. I’m never gonna get it.

If you’re not reviewed by the New York Times (or seen on Oprah) your book is gonna have tough, tough sledding to gain awareness in the marketplace. No book I publish under Black Irish is going to achieve wide awareness. BI’s reach is too tiny. Our penetration of the market is too miniscule. And even being published by one of the Big Five, as The Lion’s Gate was by Penguin in 2014, is only marginally more effective.

There are maybe a hundred writers of fiction whose new books will be reviewed with any broad reach in the mainstream press. Jonathan Franzen, Stephen King, J.K. Rowling, etc. I’m not on that list. My stuff will never receive that kind of attention.

Does that bother me? I’d be a liar if I said I didn’t want to be recognized or at least have my existence and my work acknowledged.

But reality is reality. As Garth on Wayne’s World once said of his own butt, “Accept it before it destroys you.”

On the other hand, it’s curiously empowering to grasp this and to accept it.

It forces you to ask, Why am I writing?

What is important to me?

What am I in this for?

Here is novelist Neal Stephenson from his short essay, Why I Am a Bad Correspondent:

Another factor in this choice [to focus entirely on writing to the exclusion of other “opportunities” and distractions] is that writing fiction every day seems to be an essential component in my sustaining good mental health. If I get blocked from writing fiction, I rapidly become depressed, and extremely unpleasant to be around. As long as I keep writing it, though, I am fit to be around other people. So all of the incentives point in the direction of devoting all available hours to fiction writing.

I asked hypothetically in last week’s post, What if a writer worked her entire life, produced a worthy and original body of work, yet had never been published by a mainstream press and had never achieved conventional recognition? Would her literary efforts have been in vain? Would she be considered a “failure?”

Part of my own answer arises from Neal Stephenson’s observation above.

I wrote for twenty-eight years before I got a novel published. I can’t tell you how many times friends and family members, lovers, spouses implored me for my own sake to wake up and face reality.

I couldn’t.

Because my reality was not the New York Times or the bestseller list or even simply getting an agent and having a meeting with somebody. My reality was, If I stop writing I will have to kill myself.

I’m compelled.

I have no choice.

I don’t know why I was born like this, I don’t know what it means; I can’t tell you if it’s crazy or deluded or even evil.

I have to keep trying.

That pile of unpublished manuscripts in my closet may seem to you (and to me too) to be a monument to folly and self-delusion. But I’m gonna keep adding to it, whether HarperCollins gives a shit, or The New Yorker, or even my cat who’s perched beside me right now on my desktop.

I am a writer.

I was born to do this.

I have no choice.

September 23, 2016

Pitching, Productivity & Strangers: That’s Not How It Works

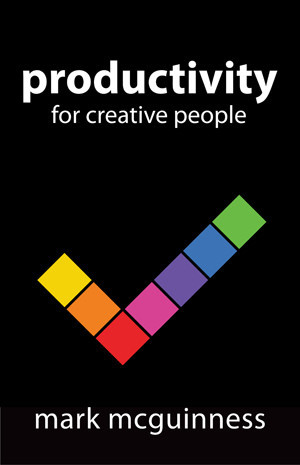

Mark McGuinness has a new book out. He’s giving it away for free.

Mark McGuinness has a new book out. He’s giving it away for free.

I haven’t read it yet, but I’m suggesting you check it out.

Why?

Trust.

I know I’ll respect whatever Mark produces.

That’s Not How This Works

Last week a pitch letter from a stranger arrived. The stranger has a book idea and wants to obtain a signed author contract with a publishing house before he writes his book. In order to achieve this goal, the stranger explained that he is requesting support from established authors. He wants the established authors to provide an endorsement for his book idea.

Breakin’ it down:

The stranger doesn’t have a book to review.

The stranger has a book idea he’d like supported.

The stranger doesn’t have a relationship with the established authors.

The stranger wants established authors to spend their time on his work.

The stranger doesn’t have a proven track record.

The stranger wants authors to trust him and lend their names to his unproven work.

As I read the pitch, an Esurance commercial — the one with the woman posting pictures to the wall of her home — came to mind. She and her friend start disagreeing and her friend says, “That’s not how it works. That’s not how any of this works.”

You know that saying “time is money?” When you ask an author to spend his time on your work, you’re asking him to give up time that he could spend on his own work, which means you’re also asking the author to give up money. Instead of the author making an investment in his own work, he’s making an investment in your work.

Why would he do that? He doesn’t know you or your work.

That’s an ask you’ve got to work into. It requires getting to know the author, showing that you’ve taken the time to familiarize yourself with the author’s work, and it takes doing some work on your own. We’d all like a book contract without writing the book first, but that’s not how it works for most authors — especially when those authors are first-time authors. Usually the book comes before contract — or a large portion of the book-in-progress is available to submit with the contract.

Back to Mark McGuinness.

Mark didn’t ask me to share his book. I learned about the release because I subscribe to his site. I subscribe to his site because I value his work. Part of the reason I value his work is because I’ve had the honor of being in touch with the gentleman behind the work.

He’s not a stranger.