Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 70

May 27, 2016

Always be Closing

So you’ve got a cover image that you’re happy with.

Alec Baldwin in Glengarry Glen Ross…remember your ABCs

The title and the image Yin and Yang around the territory of the global theme of the work.

You’ve also got a solid short quote from a respected source and/or a respected figure in the book’s genre featured prominently on the front. Something like “The best book on extreme spelunking bar none!” –Lon Fuller

So you’re done right?

NOPE.

Don’t forget the back cover copy.

This is a fundamental mistake self-publishers make again and again.

They go all the way to the finish line and then they half ass the back cover.

Hey, I’ve done it myself. The back cover is the last battleground with book packaging Resistance. It’s the place when we just want the damn thing to be over with.

We’re exhausted. We went through 30 different cover ideas and almost destroyed our relationship with our designer.

We’ve burned every bridge possible calling in every favor we can to get advance quotes. Now we just want to get this sucker out in the marketplace so we can move on with our lives.

Totally understandable.

Now go have a cup of coffee and then close this sucker. Burn through this last grind and don’t quit until you’re sure the copy is as good as it can be.

So what are you going to write?

Keep it simple.

Have a tagline at the top of the back cover.

Do two paragraphs of body copy that explain the three stages of the book (beginning hook, middle build, ending payoff) in a dynamic way.

End with an author bio (and perhaps photo too if you can make it look good).

Realize that it will never be perfect…

So Steve has a new book at the printer now that we’ll be bringing out very soon. (Don’t worry all of our peeps who are part of First Look Access, which you can sign up for here, will get preferential treatment before it goes wide…)

What did we decide to use as our tagline at the top?

FROM THE AUTHOR OF THE WAR OF ART…

We’re cool honing in on that single simple eight-word pitch because the book is perfect for anyone who’s read, heard of, or is mildly interested in The War of Art.

Steve’s new book isn’t for everyone…so we didn’t try and pitch everyone.

Obviously, you don’t need to read The War of Art to go mad for the new book. I won’t spoil it here, but let’s just say it has a very provocative title.

So the trick for the back cover copy is to CLOSE THE SALE!

So one way to CLOSE THE SALE is to speak to people you absolutely know will be ready to buy.

Don’t try and convince people who aren’t inclined to turn over the book and read the back cover!

Because guess what? They haven’t even made the choice to read the back cover copy. And if you write your copy for those who don’t really care…you might turn off your core audience.

There is nothing more off putting than generic back cover copy written to no one in particular. A book is an invitation to deepen a person’s relationship to the author…even if they’ve never read anything by him/her before.

So write copy that speaks to the reader you know will love the book.

If you’ve written a thriller about online gaming…use language that online gamers use so that those people will see the book as authentic. Not some lame attempt by a 50-year-old editor trying to get a piece of that hot new market. The copy needs to sound like something the reader has heard tangentially in his chosen area of interest or something he understands deeply.

So for those two body paragraphs after the opening hook of the tag line…use the strength of the book’s theme as represented by its inciting incident to compel the reader to just BUY THE THING ALREADY.

“What if an insatiable killer shark starting eating Hamptons summer swells and the only person capable of stopping the shark is terrified of getting into the water?”

“What kind of man has the inner fortitude to defend a society’s scapegoats from the prejudice and tyranny of a nation’s starving underclass?”

“Is there ever a time to forgive an unforgivable act of malice?”

Use the story to sell the story.

Lay down the landscape of emotional terrain for the reader with a juicy question for them to ponder so that they “get it.” They’ll understand the genre the book is living in just from that question. They’ll understand the stakes involved in the story (the central value inherent in each external and internal genre must be conveyed in the back cover copy) and they’ll understand what generally the ending payoff of the entire thing will be just from that question.

What you need to do with the back cover copy is build up the reader’s expectations and make them promises that you will pay those expectations off in ways that they will never see coming.

Use the back cover copy to Close the sale. ALWAYS BE CLOSING.

And if the book delivers on those promises, it will be discussed among the lovers of that particular genre. And it will gain word of mouth. It will live.

Lastly, if you have a renowned author with incredible bona fides, don’t waste them!

Put his/her bio (and if they’re interesting and warm looking too…their photo) on the back cover so that anyone still not sure to try it will be convinced by this last bit of salesmanship.

The subtext of the bio/photo is “Dude, this woman or man is awesome…you’re not going to find an expert better than her or him…so buy it!”

And keep the whole thing under 250 words.

May 25, 2016

Cover the Canvas

Is the first draft the hardest? Is it different from a third draft, or a twelfth? Does a first draft possess unique challenges that we have to attack in a one-of-a-kind way?

Cover it, baby!

Yes, yes and yes.

A first draft is different from (and more difficult than) all subsequent drafts because in a first draft we’re filling the blank page. And we know what that means: Resistance.

We were talking last week about the “Blitzkrieg method” for attacking a first draft. Here’s another way of thinking about it. This is my main mantra for first drafts:

“Cover the canvas.”

I think of myself as a painter standing before a big blank canvas. What is my aim in a first draft? I just wanna get paint on every inch of that canvas. I know I’m done when I can stand back and see color from end to end and top to bottom.

Imagine we’re Leonardo and we’re laying out “The Last Supper” (in other words, a first draft). Here’s what we want to do. We want to sketch in the apostles, get an outline of Jesus in the center, get the supper table down so it works nicely from left to right and right to left. And we want the perspective in the background. Beyond that, we will not sweat the details. It doesn’t matter if Matthew’s hair isn’t right, or Peter’s left hand has four fingers. We’ll fix that later. Get the picture down. Cover the canvas.

I’m working on a first draft right now. I’m into it about two months. It’s half done. I’ve got one scene that I know in finished form will be about two pages long. Right now it’s twelve. I’ve got repeats, digressions, all kinds of weird stuff in there. It doesn’t matter. I’m happy. I’ve got paint on that part of the canvas.

Another sequence in finished form will be probably forty pages. Right now it’s one sentence. It’s a big TK (“to come.”) I’m fine with that. At least I’ve got SOMETHING as a place holder. I’m covering the canvas.

Why is it so helpful to think of first drafts in these terms? Because in the first draft, Resistance is at its most powerful. First drafts are killers. The blank page, day after day is a monster. Fighting that fight, we give Resistance ten thousand chances to come up with reasons for us to quit. If we dawdle on our first draft, even good external news can destroy us. A raise, a new baby, a winning lottery ticket. Aw hell, there goes our symphony.

Some smart son of a gun once said, “There’s no such thing as writing, only re-writing.” He was wrong. The first draft is writing. Pure blue-sky, blank-sheet writing. But he was right too. Because after Draft #1, it’s all rewriting.

That’s our goal in a first draft: to get to the point where we can start re-writing.

Lemme say it again: Our enemy as artists is Resistance. If we make the mistake in our first draft of playing perfectionist, if we agonize over syntax and take a week to finish Chapter One, by the time we’ve reached Chapter Four, we’ll have hit the wall. Resistance will beat us.

But if we can stay nimble and keep advancing, slapping paint on the canvas and words on the page till we’ve got something that works from east to west and north to south, however imperfectly, then we’ve done our job.

Remember, we’ll probably do ten drafts or more before we’re done. Those drafts are for fixing the stuff we laid in roughly in Draft #1. But by putting paint in every square inch, we’ve laid the groundwork for those subsequent drafts. There’s lots left to do but we’ve established a beachhead now. We’ve got something we can work with.

Cover the canvas. It works.

May 20, 2016

Don’t Swing Big All the Time

In The Science of Hitting, by Ted Williams and John Underwood, there’s a a section titled “Smarter is Better,” which starts out by talking about Frank Howard, then of the Senators.

In The Science of Hitting, by Ted Williams and John Underwood, there’s a a section titled “Smarter is Better,” which starts out by talking about Frank Howard, then of the Senators.

“He hit a lot of home runs, he’s the strongest man I’ve ever seen in baseball, but he wasn’t getting on base nearly as often as he should. He struck out a lot, he swung at bad pitches, he swung big all the time.”

When Williams finally had an opportunity to work with Howard, they focused on NOT swinging big all the time.

“Halfway through the 1969 season he had almost as many walks as he drew the entire previous season. He wound up with 102 and cut his strikeouts by a third. His average was higher than ever, he scored more runs, and he still hit more home runs, some of them out of sight. In 1970 he led the league in home runs (45) and RBIs (140) and walked 130 times.”

For the non-baseball fans, this boils down to one thing: Once Howard stopped trying to crush every ball that came his way, his stats improved.

I met another author last month, whose goal was to make it to the New York Times bestseller list. He knows that first-time authors have made the list. He ignores the greater number of first-time authors that haven’t made the list, as well as the long-time successful authors who haven’t made the list.

His goal is to hit home runs and only home runs.

As Williams wrote, “you can’t beat the fact that you’ve got to get a good ball to hit.” For publishing, it might mean you have an amazing book, but the time just isn’t right for it. Think of the long list of artists that didn’t gain recognition until after they died. In baseball terms, you could be an amazing hitter, but you need “a good ball to hit.”

If you ask a group of Little League player their goals, you’ll hear many of them say they want to hit homeruns. Their goal, instead, should be to get on base.

That should be your goal, too — even if it means getting there because a pitcher sent four balls your way and you walked to first base.

Too often the goal is the New York Times bestseller list, when it needs to be “to get on base.” Get in the game first and then adjust your goal. You’ve got to be able to play at the basic level in order to reach and maintain higher levels.

Or, you could be like Frank Howard was, swinging hard every time, but not always getting on base. Once he mastered more than one way of responding to the pitch, he changed his game.

So what does that look like for authors?

It means walking and advancing on errors, and all the other ways to get in the game that aren’t as sexy homeruns. It means writing op-eds and articles for small publications as you grow toward the big ones, publishing’s version of playing in the minor leagues before making it to the majors. It means learning about all aspects of publishing at a lower level, so that you have what it takes to advance at the higher level. It means building your platform, starting at zero.

When Howard played for the Dodgers, he struggled to the point of submitting a letter of resignation, stating he was quitting baseball. Instead, a change of mind and a trade landed him in Washington, D.C., with the Senators and Williams. The rest is history.

Remember: Homeruns get the crowds cheering, but what get’s them sticking with you is consistency and quality, of you showing up and getting into the game series after series, and season after season. Fans are fickle. If you want to be a one-hit wonder, they’ll stick with you for a while, but if you want a career, you’ve got to show them you have the chops and discipline to maintain it.

May 18, 2016

The Blitzkrieg Method

Continuing our new series on First Drafts …

Gen. Israel Tal of the Israel Defense Forces, before a Merkava tank which he designed

Blitzkrieg is German for “lightning war.” It’s a technique of battle that was developed in the ‘30s by certain German and British generals, foremost among them Heinz Guderian, and put into practice with spectacular success by the Germans in the assaults on France, Poland, and the Soviet Union at the start of WWII.

Blitzkrieg is also a great way to write the first draft of a novel.

The first principle of blitzkrieg is break through the enemy and drive as fast as you can into his rear areas.

In blitzkrieg, the attacking force stops for nothing. If it encounters heavy resistance in one area, it simply bypasses that area and keeps advancing. This works in war because the bypassed enemy, fearing it will be cut off from resupply and reinforcement, often packs up and runs without firing a shot.

Blitzkrieg is psychological as much as physical. The attacking force is energized and empowered by its orders to be aggressive, to strike hard and fast, to keep moving no matter what. The attacking force is fortified emotionally by the knowiedge that it possesses the initiative, it is dictating the action. The enemy can only react. We, the attacking force, can act.

This is exactly the mindset that the novelist needs in writing a first draft.

Those empty pages that lie before us … they are not neutral. They are dug in, ready and eager to resist us. Their power is Resistance. Those blank pages are the equivalent of hundreds of miles of barbed wire, minefields, bunkers and powerfully-entrenched defensive forces.

How are we going to overcome these forces, particularly when we ourselves may be outnumbered, outgunned, out-resourced?

Blitzkrieg.

Hit the enemy fast, hit him hard, get into his rear and throw his forces into confusion.

In last week’s post, we cited a technique described by novelist Matt Quirk. He calls it “using TK,” meaning the editor’s mark for “to come.” When we hit a difficult spot in our first draft, Matt says, simply write “TK” and keep moving. We’ll come back later, he says, and mop up that pocket of resistance.

This is blitzkrieg.

This is lightning war.

The weapons of blitzkrieg are illuminating for us novelists as well. They are weapons of speed and mobility, weapons meant to move fast rather than bring to bear overwhelming firepower. Tanks, aircraft (particularly dive bombers and fighter planes used in close support of ground troops), and mechanized infantry are the arms of blitzkrieg. Their role is not to pulverize the enemy in a straight-up slugfest, but to break through his defenses using speed and audacity and to drive as quickly and as deeply as possible into his rear areas.

That’s your job and mine as novelists in a first draft. Start fast. Roll hard. Stop for nothing. Bypass strongpoints of the enemy. Get to the final objective—THE END—as quickly as we can, even if it means we’re ragged and exhausted and running on fumes.

In June of 1967, the Israeli armored division under Gen. Israel Tal lay poised on the Egyptian frontier, knowing it was going to have to drive through seven enemy divisions to reach its objective, the Suez Canal, on the far side of the Sinai desert. Here is how Gen. Tal concluded his address to his troops:

Now I’m going to tell you something very severe. En brera. “No alternative.” The battle tomorrow will be life and death. Each man will assault to the end, taking no account of casualties. There will be no retreat. No halt, no hesitation. Only forward assault.

Our novel, yours and mine, is life and death too. The enemy, Resistance, will employ every ruse, every stratagem, every dirty trick to sap our will and break our momentum. His ally is time. The longer he can drag out the fight, the more likely you and I will be to run out of resources, to lose our will, to quit.

The last thing you and I want, embarking on the first draft of a novel or a screenplay, is to get bogged down in a war of attrition. Resistance is too strong. It will defeat us if we let it suck us into a grind-it-out struggle in the trenches.

Strike fast. Strike hard. Stop for nothing till you reach the objective.

Momentum is everything in a first draft.

May 13, 2016

My One Fail-Safe Rule for Packaging

If I had to give one and only one piece of advice about how best to generate a cover for a book, it would be this:

Yin and Yang the Image/s and the Word/s.

Huh?

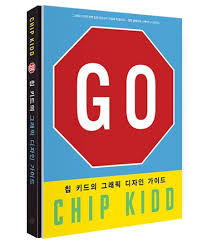

Here’s Chip Kidd’s cover for his book on graphic design that I highly recommend…

It’s supposedly for kids and kids will absolutely love it, but I find it remarkably helpful too. And I’m on the back nine of my life:

See what I mean? It even works in translation…

The image and words don’t match, which is inherently intriguing.

Here’s one more example.

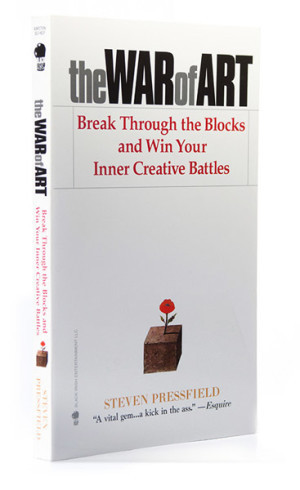

The paperback cover for The War of Art features an image created by the master of design…Milton Glaser, he of the I Love New York campaign and an absolute hero in innumerable ways.

I would love to take credit for the vision behind the paperback cover of The War of Art but I had nothing to do with it.

Back in my Rugged Land days (the perfectly aligned long-tail publishing company I started up before the ubiquity of Internet commerce, sometimes you get ahead of the market, timing is everything…) I published The War of Art in a super tricked out hardcover edition. The book sold well (a little under 10,000 hardcovers) but as a newbie publisher I decided to license paperback rights to Grand Central Publishing. GCP is a division of Hachette, one of the Big Five.

I’m the first to criticize Big Five’s standard operating procedures, but in this case, the process and professionalism of GCP’s art department and the editor who acquired the rights (Emily Griffin) really paid off. Emily is now at HarperCollins.

What my art director (the brilliant Timothy Hsu) and I went for the hardcover was to create a book that required the reader to self examine. So the cover was a sleek grid-like mosaic that had three tiny mirrors embedded. It was “paper/grid over boards.” The idea was to attract artists from any and all walks of life. I’m pleased with how it worked and it certainly did enough business to attract a major publisher’s paperback interest.

What Emily and GCP did though was to focus the book and target a very reliable market.

They decided that the paperback edition would be best served by directing it to writers. This makes absolute sense because paperbacks back then (and now) are quickly categorized in bookstores and stuck in particular shelves. Remember that this was the era of Amazon.com as a cute little online site…not the powerhouse it is today. There were no search engines that instantly gratified back then.

So Emily asked Steve if she could tweak his subtitle which was WINNING THE INNER CREATIVE BATTLE for the hardcover edition to: BREAK THROUGH THE BLOCKS AND WIN YOUR INNER CREATIVE BATTLES for the paperback.

Steve’s attitude then (and it still is today) is to cede control over the work he’s created to passionate professional advocates…even if he’s not 100% sure of what they are suggesting. Especially if he isn’t.

Emily Griffin was madly in love with The War of Art and she made a very strong case why we needed to change the subtitle and laser focus on writers. Her argument was air tight.

Obviously, the easier it is to get your book into a bookstore shelf, the better the chances of the book actually selling. Every single bookstore has a reference/writing section. If we marketed the book primarily to writers, we’d stand a good chance of getting slotted in that self-selecting section of the bookstore.

Steve signed off willingly.

And then they sent us the cover, which we both knew was perfect. It was perfect because it softened the title.

The image (a flower growing out of a block of cement) was the Yin to the title’s Yang.

Don’t forget that Steve spent years in advertising and he’s no rube when it comes to packaging, marketing, advertising etc. When he was flat broke, he was always able to get a job on Madison Avenue to refill his coffers. He’s a pro and no pushover.

The thing about the title The War of Art that Steve and I feared when we debated it is that creatives/artists are often resistant to the word WAR.

Conflict (even though it’s indispensable to any art) is not the thing people associate with art. Or want to. They want to think of art as beauty, which it certainly is. But conflict begets beauty. Ask any woman who has given birth if the process was conflicting… And no matter how odd looking, there isn’t anything more beautiful than a new baby.

I know it’s an unreliable generalization to say that creative/artists don’t want to think of the creative process as “War.” And it’s obvious untrue today after the hundreds of thousands of copies that The War of Art that have sold, but back then it was a real concern.

The title really could have backfired on us and destroyed the book’s ability to find an audience. Seriously, sometimes a title kills a book. Or the image on the cover does. But if you can Yin and Yang them, chances are they’ll intrigue…not repulse.

So back to my one ironclad, fail safe packaging rule. When in doubt, make your cover image “say” something antithetical to the title.

May 11, 2016

The Magic of TK

On Shawn’s storygrid.com this week there was such a great piece that I’m ripping it off lock-stock-and-barrel here to share with my peeps. It’s on the subject of writing a first draft.

Matt Quirk, author of “The 500” and “Cold Barrel Zero”

Matt Quirk is a novelist (The 500, The Directive, Cold Barrel Zero) and a friend and client of Shawn’s. Here’s his secret weapon for getting through a first draft:

Use TK. This is the essential lubricant of the rough first draft. It’s a habit I learned from working as a reporter, but didn’t realize the novel-writing magic of it until I read this advice from Cory Doctorow. TK is an editing mark that means “to come” and is equivalent to leaving a blank or brackets in the text (It’s TK, not TC, because editorial marks are often misspelled intentionally so as not to confuse them with final copy: editors write graf and hed for paragraph and headline).

Can’t figure out a character’s name? “EvilPoliticianTK.” Need to describe the forest? “He looked out over the SpookyForestDescriptionTK.” Need that perfect emotional-physical beat to break up dialogue? “BeatTK.” Just keep writing. TK a whole chapter if you want. Those blanks are not going to make or break anything big picture. Come back for them once you’ve won a few rounds against the existential terror of “Is this whole book going to work or not?” There’s no sense filling in the details on scenes that you’re going to cut.

I’m onboard 100% with this trick of Matt’s. What he calls “the existential terror of ‘Is this whole book going to work or not?’”, I would call Resistance.

The enemy in a first draft, remember, is not faulty dialogue, substandard characterization, or lack of expositional detail. The enemy is Resistance.

Resistance will try to break our will by overawing us (by its voice that we hear in our heads) with the length of the project, the scale of its ambition, the hell of the interminable slog to get from CHAPTER ONE to THE END.

Our ally in this struggle is momentum.

Get rolling and keep rolling, that’s our mantra. Let nothing stop us. Don’t slow down for anything. Keep going at all costs. Get to the finish of Draft One, no matter how lousy it is or how full of holes.

That’s the genius of TK.

As Matt says, when you hit a sticking point, don’t bog down slugging it out. That’s what Resistance wants us to do. Resistance wants us to lose momentum. It wants to wear us out fighting hand-to-hand in the trenches.

Instead slap in a quick “TK” and keep rolling.

I’m working on a first draft now myself and, trust me, it is loaded with TKs. Some of my TKs are forty pages long. I’ve got one giant sequence that I’m sure will take me a month to write. Right now it’s just a big TK.

Have you read David Allen’s book Getting Things Done? It’s probably the best time management book ever written. Mr. Allen’s key concept is that he sets up a system whereby, when Something You Have To Do But Don’t Have Time For Right Now comes in, you simply slot it into a “place holder” position. In other words, a TK. Then you drop it from your mind and go back to work.

This succeeds brilliantly because, with that Something We Have To Do securely tucked into the System, we know we won’t forget it. We’ll come back to it when we have time and we’ll take care of it. What we’ve achieved by slotting it into the System is we’ve robbed it of the potential to disrupt our flow, to break our momentum.

In first drafts, remember, velocity is everything. Quality can come later. Slug in those TKs and keep motating.

[Today’s post, by the way, marks the end of our series on Theme. For the next few weeks we’re going to talk about nothing but first drafts.]

May 6, 2016

The Social Media Skinny

Last month a nonfiction author-in-progress told me she has over 20,000 Twitter followers, which she interpreted as a sales forecast. While she knows 20,000+ followers might not equal 20,000+ book sales, to her, 20,000+ followers do equal thousands of book sales.

I gave her my spiel about being careful to avoid equating social media numbers with sales, that followers often “like” and “tweet,” but don’t always take action. She replied that she might be the exception, as many of her Twitter followers are journalists who follow her work. In the sage words of Bart Simpson, “au contraire mon frère.” Those many journalists are actually a guarantee that she isn’t the exception, but the rule, as journalists are known for contacting publishers/authors to obtain free books.

However, while the journalists can’t be counted on to buy books, they can seed and feed conversations, which will help generate book sales.

While she’s writing her book, I suggested that she place an op-ed here and there, connect with different journalists about her work, establish herself as a source for a wider group of journalists. Get them digging and talking. Same can be done with her other followers. Give them something to talk about. Don’t wait for the book. Get them chatting now.

From her current mountaintop, the author-in-progress still expects the journalists to buy her future book. What she needs is for the journalists — and all others Twitter followers — to start conversations about her book.

You Need A Conversation

Conversations spark the success of products and ideas, helping them garner new fans and break into different markets.

After Jon Snow rejoined us for Sunday nights, social media exploded with comments about the character’s future. Similar, and earlier, conversations about Game of Thrones are what brought me to the show a few seasons late, and led me to purchase and listen to every audiobook in the series.

After my car battery died during rush-hour traffic, with two kids freaking out inside it, I found myself frazzled and a block down the road from two garages. I walked up to the one friends had shared stories about — conversations related to the garage’s quality service and reasonable prices. Later, when I looked the garage up online, I found its Twitter account with a small handful of followers. Low numbers, but high conversation.

Don’t ignore the numbers, but don’t make them your focus, either. Put your eggs in the conversation basket.

You Need To Connect

Last week, another author told me he’d heard that social media is important. First-time author, older demographic, not of the Social Media generation. Knows about it, doesn’t use it.

This author is in for the long-haul. He’s in the nonfiction world, interested in writing more books and related products, and in setting up his own site with a storefront.

He’s known within the sector in which he works, so I suggested starting there, with e-mails, personal letters and phone calls. The movers and shakers on his list are within his age group, and they aren’t hanging out on social media. Get them to create/share conversations about the book. Then, on social media, use it to find like-minded individuals. Instead of posting something and waiting to see if anyone will run across it, look for people who are posting/sharing similar work/ideas. Then get to know them, gain their trust.

For example, I “like” Neil Young’s Facebook page, but it was an e-mail from his website that alerted me to his new album “Earth.” I’m not on Facebook and Twitter and everything else enough to catch every share that hits my feeds – and that’s true of so many of us. Unless you’re counting on all followers being glued to all screens, social media will be a hit and miss game.

But, if you connect with a potential customer, and the customer then signs up for your e-mail (which many of us do check every day), you’re likely to up the hits and minimize the misses.

For Steve and Black Irish Books, we’ve used social media to connect with readers. While we share new posts and products on Facebook and Twitter, we know that our readers don’t live on those screens 24/7 (and we would be upset to find out if they did), that we won’t catch them that way, so most of our efforts are on the site, growing the e-mail list and creating value.

This is the approach I’d suggest to first-time authors in particular. Don’t hop on social media and start sending tweet and post after post out about your book, how to buy your book, a new discount about your book, etc.

You Need to Value Your Time

Last weekend I spent a birthday party watching my kids and listening to another parent talk about hacking rush-hour traffic. He used historical data from his GPS device to determine the best times to drive into and out of Washington, D.C., every day of the week, down to the exact minute. He knows that Tuesday is the worst day to commute in/out of D.C., and knows when that ten minute delay getting out the door in the morning will mean an hour delay once he hits 395. So, if he’s running late, he knows if he should wait another half hour before leaving, which would mean waiting out traffic in his home instead of his car, and then arriving at work at the same time.

While he spoke, and more so once he pulled the spreadsheet up on his phone, I alternated between thinking that he was crazy and that he was brilliant. I left the party thinking he was brilliant.

The spreadsheet he created is on the intense side — and the time he put into it is on the high side, but… He found traffic trends and reclaimed chunks of his time.

Similar to rush-hour traffic, social media will eat you alive. It will suck the time out of your life.

You don’t need to be on it all the time, so figure out what makes sense, what’s the greatest ROI, and then get in and get out.

An example: For Black Irish Books, we’ve found 9 AM ET to be a good time for sending out e-mails. We’ve tried different times, but with this one, we catch the international crowd, the East Coasters and the early-rising West Coasters, and we’re all awake and working by that time in case disaster accompanies an e-mail campaign. It’s like the rush-hour hacker knowing his ten-minute window. We know what times work well for others, but we know how we fit within those times and how they work for us, too.

The Social Media Skinny Roundup: Create something of value, give them something to talk about, gain trust and protect/reclaim your time.

May 4, 2016

“Help! I Can’t Find My Title!”

Regular readers of our recent posts will know the answer to this cry for help already.

Saoirse Ronan in “Brooklyn”

Theme.

Theme is a golden highway to a great title.

Consider Brooklyn, starring Saoirse Ronan. The story is about a young Irish girl who emigrates from the Auld Sod in the early 50s and winds up in Brooklyn. After a period of struggle and assimilation she starts to find her way professionally, meets a wonderful young guy, accepts his proposal of marriage. Wow, things are going great!

A family tragedy compels her to return briefly to Ireland. Once there, her newfound American self-confidence makes her attractive to certain socially-connected individuals who might have overlooked her charms in the past. The next thing we know, our heroine is relapsing into her old, self-diminishing, allowing-herself-to-be-exploited ways. Another suitor proposes, she says yes … OMG, in the audience we’re cringing. No, Saoirse, don’t fall for it!

I won’t spoil the ending, if you haven’t seen the movie. Let’s ask instead, “What’s the theme? What is this story about?”

It’s about finding the courage to leave an old familiar world that, if we remain under its spell, will destroy our soul and our chance at self-actualization and happiness—and to venture forth (and make our home in) a new land, where true happiness and love are actually possible.

What is the name of that new land?

Brooklyn.

Voila, our title!

Another place-name that became an iconic title: Chinatown. Again because it’s on-theme.

The final line of the movie—“Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”—sums up all the corruption, cupidity, and just plain evil that lurk beneath the otherwise-attractive surface of things. In other words, the theme.

The story of an astronaut stranded on an alien orb could easily have been titled Marooned or Lost Among the Stars. What made The Martian an outstanding title (aside from its succinctness and provocativeness) was that it captured the novel’s theme—salvation comes from thinking like a whole different species of being.

Mud was a terrific title, as was Wild, The Boys in the Boat, Just Kids, not to mention The Big Short, Still Alice, Straight Outta Compton and of course Star Wars.

A great title (as Shawn wrote in his recent post, What’s in a Title?) has to hit a number of beats. It has to be provocative. It has to stop the reader and grab her interest. It has to be memorable and unique and it has to communicate the book or movie’s genre. If our novel is a love story, it can’t have a title that makes it sound like a mystery or a police procedural.

But an excellent way to start our search for a compelling title is to ask ourselves, “What is the book’s theme? What’s it about?”

With luck we might come up with Crime and Punishment or The Sun Also Rises, or even To Kill a Mockingbird.

April 29, 2016

The Designated Driver

The writer’s search for a Theme as drunkard’s walk.

I’m going to take a break from my series on packaging today to write about what Steve wrote about this past Wednesday. I know you’re Steve Pressfield fans extraordinaire and you probably had your usual “Geez that Pressfield sure knows what he’s talking about” moments a few days back.

But I think his last post is really worth another look. It certainly solidified a lot of my own ideas about the “why of writing” (and the “why of editing” too) into a far stronger internal philosophical fortress.

First some background about how this came to hit me right where I live…

Tim Grahl and I started a podcast dedicated to the principles of The Story Grid in October 2015.

Our premise was: How can an ambitious amateur fiction writer use The Story Grid as a plan of action, a do-it-yourself-manual, a reverse engineering guide…to build their novel from scratch.

So for 28 episodes, Tim has been picking through The Story Grid with me from the point of view of a highly motivated person desiring to support himself and his family writing fiction.

Just a word or two about Tim.

He’s the quintessential master of the “shadow career,” the professional life that parallels real ambition. But one that is not really “all in.” Tim had half his torso inside the primal goo of his innermost desires, but he wasn’t completely submerged.

His shadow career manifested as the founder of a company dedicated to helping writers market their books. First Tim was a “fixer,” an outside contractor for hire that people in the know would recommend as an expensive, but effective fount of knowledge. Tim would spread his secret marketing sauce over a project and get it on bestseller lists. He was a book marketing black hat…a guy behind the scenes who was paid well, but anonymous.

And then Tim decided to expand his market to people who couldn’t afford to pay his soup to nuts behind-the-scenes fees. These people were just like him before he did the due diligence to learn the best book marketing practices. They wanted to learn how to do what he did. By teaching themselves not by just hiring it out. So that they could have a repeatable skill. The capital they’d invest would be skewed to heavy-duty blue collar intellectual labor.

Why not give autodidacts the secret sauce (which really is a methodology that requires sweat labor and a few breaks…like anything else) at a fraction of the cost he was charging Big Five publishing writer/clients?

Both of those iterations of his book-publishing career did well.

Well enough in fact that he could no longer run away from what he really wanted to do with his life—write fiction.

Tim understood that he had to come out of the shadows and do what he knew deep down that he wanted to be doing since he got into this racket. He had to not just talk about it anymore. He had to do it. No matter how traumatic it would prove to be…

So he reached out to me last summer to see if I’d be interested in doing The Story Grid podcast. And when I hemmed and hawed, he made me an offer I couldn’t refuse.

He would donate his time to the project, run all of the switches to make it work, and basically just call me an hour a week and record it. He did not want anything from me but mentoring. And he’d go public with the entire process too.

What he gets is to ask me whatever he wants about storytelling and solicit specific information about how I would recommend he go about planning and generating a first draft of a novel. What I get is to share all of his struggles with people in similar situations who have no idea of where to begin the work necessary to become a Pro writer. And obviously a vehicle to keep marketing my expensive monster textbook The Story Grid to people just starting out not sure about what it is I’m recommending…

The podcast is free and you can listen to your heart’s desire here.

But it doesn’t matter if you listen to a single episode to get my point about why Steve’s last post was so important.

Okay, so what is my point? I’m getting there. I promise.

The big problem that lurked in the distant future for me (which I did a great job denying to myself) back in October 2015 was this…

What if Tim spends six months or more writing a first draft and then actually finishes it?

What will happen then?

Well, being the industrious and drip…drip…drip worker Tim is, he finished a first draft a couple weeks ago.

Now I was in a terrible position.

If I were to tell Tim;

Congratulations…but look elsewhere for editorial guidance for that first draft. I’m not going to give away my secret sauce, at least not in a podcast. I get paid a king’s ransom as a freelance editor. Instead, let’s do another episode about Inciting Incidents…

I’d certainly be within my rights.

I mean I never told Tim that I’d donate my editorial time to his novel in exchange for his doing all of the drudgery of the podcast. In fact, I keep raising the price of my private editing fees to discourage people from trying to hire me.

For me, it’s as heartbreaking to edit, as it is to write. More so because you don’t have final cut.

But if I bailed on Tim’s first draft, wouldn’t I completely disappoint all of the people who’ve invested 28 hours of their listening life to my ramblings about the power of ten as a means to evaluate a turning point’s reversibility?

Anticipating my horror at coming to this obvious irreconcilable goods crisis question “Do I help him if it doesn’t directly help me?” every single week before we went live, Tim told me not to sweat it if I didn’t want to read his stuff.

Which gave me a great sigh of relief. I’d agree and reiterate that it was best that I didn’t read his story.

I mean it could be terrible, right?

What would I tell him then?

But then like every storyteller who lies to himself that he doesn’t really need to payoff something he set up in his beginning hook if he doesn’t want to, I had to face facts.

And the facts were these:

Using the “amateur gets professional help” set-up hook to lure listeners to The Story Grid podcast and then denying payoff of the deep knowledge I have about how to confront story problems (no matter how big or small) is a shitty thing to do.

So I decided that I had to read Tim’s first draft and I had to give it to him straight no matter what…

And like 99.999 percent of first drafts, I discovered that Tim’s first draft doesn’t work. The episode when I tell him that truth airs next week.

I can’t tell you how difficult it is for an editor to explain to a writer why his first draft is nowhere near ready for prime time without destroying his confidence. And even in extreme cases his will to live…

When I was less confident in my work, there were numerous times my showing off my story knowledge to prove how great an editor I was had the worst possible effect on the writer on the other end of the phone. They’d abandon the book…or had me fired from the project. Back then I thought that they “couldn’t handle the truth.” Now I know I had a lousy bedside manner and I was the one who couldn’t handle the truth: I was overcompensating for my lack of self-confidence by being a didactic ass.

Being an editor is like being a sober friend dealing with someone who has had too much to drink.

You don’t want to his feelings or insult him (an almost inevitability), but you need to let him know that he is in no way capable of driving his own car. He’s intoxicated. (And finishing a first draft of anything is absolutely intoxicating).

The drunk (writer) needs someone else to take the wheel and get him safe and soundly home. Once he gets his equilibrium back, he can drive himself, but now he needs a designated driver.

That’s what an editor is: the designated driver who calmly lets the writer know that everything isn’t what it appears to be to him…but he has in no way made an ass out of himself either. Things aren’t so wonderful, but no one thinks the first draft writer is an idiot for thinking so. So don’t beat yourself up…just take some time to recover your sobriety and then take another look at the thing.

What in the hell does this have to do with Steve’s post from Wednesday?

It made my job telling Tim that his first draft isn’t working a lot easier.

Why?

Because Tim has a clearly identifiable THEME in his first draft.

And what that means is that Tim’s muse/unconscious spoke to him. He has the most precious of things a story requires…a central controlling idea. And it came directly from his drip…drip…drip work writing that first draft.

That theme is a gift from the Gods rewarding Tim for setting aside his shadow career and determinedly getting in the ring with his internal Resistance.

Will Tim be successful bringing that theme forward in a way that is catnip compelling to a large audience dedicated to a particular genre?

Will Tim’s first novel get him a big advance from one of the Big Five?

Can I magically transform his work and eventually Tim himself (like Henry Higgins did for Eliza Doolittle or Andy Warhol did for Nico and The Velvet Underground) into a bestselling writing titan at one of the Big Five publishing companies?

Will The Story Grid be the thing that will get the credit for Tim’s spectacular rise?

Will Tim’s novel hit a bestseller list? Will The Story Grid too?

As Steve so clearly stated in his last post, those pulse racing questions are the furies unleashed from the diabolical realm of Resistance.

What matters is that Tim is in the ring and that he’s engaging with his muse. His inner voice is speaking to him and he’s opened up the channel and is listening.

That’s all that matters.

All of that other crap is pointless. Not just pointless, it’s dangerous. It distracts you from the truth of yourself. Which is all any of us need.

So when in doubt…cling to your THEME.

If you haven’t figured your THEME out yet, find a designated editorial driver to help you find it.

That’s what Steve’s post meant to me. He succinctly pointed out what is now obvious…

THEME is just another word for…

That place we all really want to go…

Home.

April 27, 2016

“I Can’t Squeeze My Theme In!”

A couple of friends have written in:

Will Smith and Matt Damon in the movie of “The Legend of Bagger Vance”

“I know what my theme is, but I can’t figure out how to get it into my story.”

“How do I know which theme to pick?”

These are critical questions to answer because they both demonstrate a fundamental misunderstanding of what theme is and how it arises.

1) We don’t have to insert theme into our story. It’s in there already, whether we realize it or not.

2) We don’t pick your theme. Our theme picks us.

What do I mean by this? I mean a story—a novel, a play, a movie, a work of narrative nonfiction—is like a dream. Its source is our unconscious, our Muse. And just as in a dream, the totality arises organically and coheres naturally. The dream/story means something already. All we have to do as writers is figure it out.

(In many ways, this is the vital service our editors perform for us. Shawn has done it for me half a dozen times. He sees the theme that I’m blind to. He explains it to me. He tells me what I’ve already done but can’t see for myself.)

In other words, our theme is already there in the work. It’s built-in. Factory-installed.

Here’s a personal example:

The theme (or one of the themes) of The Legend of Bagger Vance is “the Authentic Swing.” Meaning a parallel and metaphor for the idea of the Authentic Self.

You and I are born not as blank slates but with a fully formed self, personality, and destiny. Our job in this life is to find that self and become it, to live it out.

That’s the theme of Bagger Vance. But I had no idea as I started the book—and even halfway through it—that this was the case. All I knew was that I was following my instincts. Characters arose, scenes appeared, a story began to take shape.

The theme was in there already.

One day as I was writing a scene, the phrase “the Authentic Swing” popped out. I knew at once that I had hit paydirt. “Ah,” I thought “this is what the story is about!”

A few weeks back we did a post titled “Analyze your story like a dream.” The idea was that Theme appears spontaneously in a story we write (as long as we’re truly following our instincts), just as meaning is embedded in a dream.

If you think about it, this is pretty amazing. We find ourselves “seized by” a story. We are compelled to write it. Why? Because on some soul-level known to our unconscious but not to us, the issue of this story is important to our evolution. Just as a dream will warn us of impending danger or encourage us or inspire us, so the novel/play/movie we find ourselves inspired to bring forth is also trying to speak to us.

What is it trying to tell us?

Its theme.

Its meaning.

Its significance.

Why is theme so hard to identify sometimes? Because every cell in our bodies (i.e., Resistance) has been laboring flat-out to keep us from seeing it. Why? Because when we see it, we will advance. Our consciousness will open. We will move one step closer to self-realization, to self-actualization.

This is why writing (or the pursuit of any art) is, to me, a spiritual enterprise. It’s an endeavor of the soul. The stories we write, if we’re working truly, are messages in a bottle from our Self to our self, from our Unconscious/Divine Ground/Muse to our struggling, fallible, everyday selves.

What is your story about?

Roll up your sleeves and do the work. Dig deep. Bust your brain. Figure it out.

I can declare with absolute honesty that every book I’ve written has unpeeled and revealed to me an aspect of my self that I had been unconscious of before I started writing the book. The philosophy behind the idea of the Authentic Swing: I had no idea I knew that, no idea I believed that. Yet I did. Completely. It is now the absolute bedrock of my view of life and death. Everything I do and believe is based on that.

I would never have known it if I hadn’t found it in my own story.

The artist’s journey is not so much about self-expression as it is about self-discovery.

That’s what theme is all about, from the writer’s point of view. It arises spontaneously in her work. It’s 100% true to her soul’s odyssey.

Another question that crops up regularly in correspondence is this: “What if I never find a publisher? What if I write book after book and no one ever even knows they’re out there? What’s the point?”

One answer (it’s a hardcore answer, I admit) is that on the deepest level it doesn’t matter if you and I ever crack Amazon’s Top 100 or hit the New York Times bestseller list. The works we produce are valid in their own right. They are telegrams to ourselves from our immortal, infallible, divinely-inspired souls.

The message is our story’s theme. We don’t have to insert it. We don’t have to invent it. It’s embedded in the work already. All we have to do is dig for it and figure it out.