Don’t Swing Big All the Time

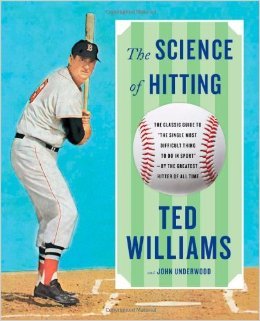

In The Science of Hitting, by Ted Williams and John Underwood, there’s a a section titled “Smarter is Better,” which starts out by talking about Frank Howard, then of the Senators.

In The Science of Hitting, by Ted Williams and John Underwood, there’s a a section titled “Smarter is Better,” which starts out by talking about Frank Howard, then of the Senators.

“He hit a lot of home runs, he’s the strongest man I’ve ever seen in baseball, but he wasn’t getting on base nearly as often as he should. He struck out a lot, he swung at bad pitches, he swung big all the time.”

When Williams finally had an opportunity to work with Howard, they focused on NOT swinging big all the time.

“Halfway through the 1969 season he had almost as many walks as he drew the entire previous season. He wound up with 102 and cut his strikeouts by a third. His average was higher than ever, he scored more runs, and he still hit more home runs, some of them out of sight. In 1970 he led the league in home runs (45) and RBIs (140) and walked 130 times.”

For the non-baseball fans, this boils down to one thing: Once Howard stopped trying to crush every ball that came his way, his stats improved.

I met another author last month, whose goal was to make it to the New York Times bestseller list. He knows that first-time authors have made the list. He ignores the greater number of first-time authors that haven’t made the list, as well as the long-time successful authors who haven’t made the list.

His goal is to hit home runs and only home runs.

As Williams wrote, “you can’t beat the fact that you’ve got to get a good ball to hit.” For publishing, it might mean you have an amazing book, but the time just isn’t right for it. Think of the long list of artists that didn’t gain recognition until after they died. In baseball terms, you could be an amazing hitter, but you need “a good ball to hit.”

If you ask a group of Little League player their goals, you’ll hear many of them say they want to hit homeruns. Their goal, instead, should be to get on base.

That should be your goal, too — even if it means getting there because a pitcher sent four balls your way and you walked to first base.

Too often the goal is the New York Times bestseller list, when it needs to be “to get on base.” Get in the game first and then adjust your goal. You’ve got to be able to play at the basic level in order to reach and maintain higher levels.

Or, you could be like Frank Howard was, swinging hard every time, but not always getting on base. Once he mastered more than one way of responding to the pitch, he changed his game.

So what does that look like for authors?

It means walking and advancing on errors, and all the other ways to get in the game that aren’t as sexy homeruns. It means writing op-eds and articles for small publications as you grow toward the big ones, publishing’s version of playing in the minor leagues before making it to the majors. It means learning about all aspects of publishing at a lower level, so that you have what it takes to advance at the higher level. It means building your platform, starting at zero.

When Howard played for the Dodgers, he struggled to the point of submitting a letter of resignation, stating he was quitting baseball. Instead, a change of mind and a trade landed him in Washington, D.C., with the Senators and Williams. The rest is history.

Remember: Homeruns get the crowds cheering, but what get’s them sticking with you is consistency and quality, of you showing up and getting into the game series after series, and season after season. Fans are fickle. If you want to be a one-hit wonder, they’ll stick with you for a while, but if you want a career, you’ve got to show them you have the chops and discipline to maintain it.