Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 69

July 13, 2016

The Spine of the Story

Here we are, getting set to plunge in on our first draft.

The Golden Gate bridge. Our story’s spine should be as simple and as strong as this.

But what do we do before that?

We said a couple of weeks ago that our first question to ourselves, pre-pre-first draft, should be:

“What’s the genre?”

Okay, great. Let’s say that we’ve done that. We know our genre. Our story, we’ve determined, is a sci-fi action-adventure. Or maybe it’s a love story. Or a Western combined with a supernatural thriller.

Good enough. We’ve got that covered.

What’s next?

For our answer, let’s refer back to Paul (“Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull”) Schrader’s excellent guidelines for pitching:

Have a strong early scene, preferably the opening, a clear but simple spine to the story, one or two killer scenes, and a clear sense of the evolution of the main character or central relationship. And an ending. Any more gets in the way.

Ah, “ … spine to the story.”

Let’s call that our second question to ourselves.

“What is our story’s spine?”

(Myself, I think of this in slightly different terms. I think of it as “Beginning, Middle, End.” “Act One, Act Two, Act Three.” “Hook, Build, Payoff.“)

No worries, it’s all the same thing. We’re asking ourselves “What’s the backbone of our story? What narrative architecture supports our tale from beginning to end?”

For our purposes now [pre-pre-first draft], this doesn’t have to be much. It can be as simple as this:

Ahab sets out after Moby Dick. Ahab chases Moby Dick around the globe. Ahab catches up with Moby Dick and fights him to the death.

Or this:

Harry and Sally are best friends but not lovers. Harry and Sally begin to realize that they’re in love with each other. Harry and Sally become friends and lovers.

Why can this part of our pre-pre-first draft (our Foolscap file) be so simple? Because all we really need to assure ourselves of at this stage is, “Will this idea work as a story? Does it have a beginning, a middle and an end? Does it go somewhere? If we can write enough strong scenes adhering to this narrative spine, will a reader be hooked at the start, have her interest held through the middle, and feel satisfied emotionally and intellectually at the end?”

That’s the job of the story’s spine.

If we can answer yes to all the questions above, that’s all we need at this point.

The Terminator comes back from the Skynet machines-versus-humans future to kill Sara Conner (who will be the mother of John Conner, the brilliant rebel leader who will fight Skynet in the future). Sara Conner and Reese (a fighter sent back in time by the embattled rebels in the future) flee from the Terminator as they themselves fall in love and plant the seeds of John Conner. Sara and Reese battle the Terminator to the death and, for the moment at least, defeat him.

That’s a great spine, a strong and sturdy Act One, Act Two, Act Three. If we’ve got that much at this early stage, we are doing great.

So, to recap …

Our pre-pre first draft now has established answers to two questions. One, “What’s the genre?” And two, “What’s the story’s spine?”

That’s a lot.

We’re rolling now.

We can feel very good about ourselves because we’re working as professionals and not as amateurs. We’re laying the groundwork for what is to come—the stable, strong foundation of the edifice. We are setting ourselves up to succeed and not to fail.

Next week we’ll address Question #3 of our pre-pre first draft—a subject we’ve examined before:

“What’s the story’s theme? What is it about?”

July 8, 2016

Hug the Sh*t

There’s a scene in Fredrik Backman’s book My Grandmother Asked Me To Tell You She’s Sorry when Elsa, the main character, recalls a piece of advice from her grandmother:

Granny always said: “Don’t kick the shit, it’ll go all over the place!”

Why should this advice matter to you?

While Granny never out and out says it in the book, the unsaid yin to the yang of her advice would likely be:

Hug the sh*t.

Sh*t in this context is anything that gets in the way of what we want to do, anything unexpected that pops up and has us exclaiming “sh*t” or “shoot” or whatever your word choice is for such situations. Smells a lot like Resistance. The trick is to turn the sh*t around, to use it for good. Think fertilizer instead of nuisance.

In this post, examples of sh*t come courtesy of the recent ebook giveaway of Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t.

The Mobi/Firefox Sh*t

The Mobi file for the ebook wanted to open up, rather than download, for Firefox users. The result? Firefox users were presented with gibberish on their screens. Of the thousands that downloaded the ebook, less than 100 contacted us about this issue. Of that 100ish, a few e-mailed to give us a head’s up, and note that they sorted out access on their end (right click on the Mobi file image, rather than click on the Mobi file image), while the others assumed the link was bad, that we weren’t using a good service, that we were up to no good and literally providing sh*t.

How to handle this sh*t?

We e-mailed this group and advised them how to access the file and/or offered a print edition. The majority of the individuals were fine, but a few still couldn’t access the files. No luck period. A free print edition was offered to a number of people in this group.

Side note: When it comes to ebooks, one group will always consist of technically-challenged individuals. Even if your files are perfect, this group will not know how to access the files because they don’t know how to use their devices. Even if you make it as easy as possible, some will never sort out access to your files. Offering them a free edition when available has been our route in the past. It’s better to help than to restrict access to the one route they can’t sort out.

The Server Sh*t

We were overloaded and ran into an issue with the server for a short period. The result? Though it was a blink of a period, individuals trying to access the free download during that blink ran into problems. The files timed out, wouldn’t download?

How to handle this sh*t?

We e-mailed the individuals to sort out what was going on, apologized, and offered a free print book in most cases.

The E-Mail Sh*t

A few individuals scanned the e-mail with the free offer. Instead of clicking on one of the file images, this group clicked on the “more information” link, which directed to the sales page. The result? Once they bought the book, and then learned more about the free ebook via friends, other newsletters, etc., they became upset. In their minds, we should have offered the book for free first (which is what we did), before offering it for sale.

How to handle this sh*t?

The child side of me wanted to point out this group’s error, but the adult side learned a lesson. The “more information” link was sized on the large side. It pulled in the eyes. In the future, we’ll rethink the sizing and where the eyes are drawn. For now, we apologized for the confusion and refunded the cost of the book and shipping. Should the reader of the email have paid more attention? Yes. Could we do a better job making things as simple as possible? Yes. We can always do more.

As a side note on the e-mail, I had wanted to add a place within the e-mail for people who were interested to sign up for the Black Irish or Steven Pressfield mailing lists, too, but Shawn thought that might be too confusing. He was right. Had we done that, it’s likely that we’d have a group that felt they’d have to sign up to receive the promo. In the end, new people did sign up for more info. and they did it on their terms. Lesson learned: Keep things simple.

Hug the Sh*t

In the natural world, sh*t is a fertilizer. Rather than being a nuisance, it helps things grow.

One of the greatest lessons Black Irish Books has learned is that sh*t is a great way to grow relationships, hence all the outreach mentioned above, in the “how to handle this sh*t? sections.” While there are miserable people out there, the majority of those contacting us with one issue or another have been amazing. Some sh*t happens on our end, they reach out to give us a head’s up, and once we connect, relationship seeds are planted. The sh*t they contacted us about is potent fertilizer, rather than the variety of crap you drag your shoe through the grass to remove.

While my schedule could do without the sh*t, the Black Irish Books business can thank the sh*t for helping it grow.

So, as Granny might say,

“Don’t kick the shit, it’ll go all over the place!” Hug the sh*t instead.

July 6, 2016

Dudeology #2: Combining Genres

We were talking last week about The Big Lebowski being a film in the Private Eye genre. But what really makes Lebowski so inventive and so interesting is it’s a mixed genre. It’s a Slacker/Stoner tale (like Dazed and Confused, Go, Clerks, or any Cheech and Chong movie) conceived, structured, and executed as a Detective Story.

Sam Elliott in The Big Lebowski. “Now this feller, the Dude … I think he figgered out something new.”

What does this mean for you and me as writers?

It means that mixing genres is one of the most canny and fun tricks we can pull to come up with something new and fresh and exciting.

Mix the Private Detective genre with Sci-Fi and you get Blade Runner.

Combine it with a Geezer Pic and you get The Late Show, starring Art Carney and Lily Tomlin.

Blend it with historical fiction and you get The Name of the Rose.

But let’s dig a little deeper into The Big Lebowski. The concept of the film is this:

Let’s tell a story that hits all the beats [conventions] of a Sam Spade/Philip Marlowe Private Eye Story, but instead of having a hard-bitten detective as the hero we’ll have a sweet, lovable stoner.

How does that pay off for the writers, Joel and Ethan Coen? It pays off because this simple creative twist—stoner instead of film-noir private eye—makes every character and line of dialogue feel original and inventive. Each scene gives the filmmakers an angle to make a fresh point about America, about popular culture, about how things have changed in the past generation or two.

Consider this comparison:

Here’s Jack Nicholson as Jake Gittes in an obligatory moment from Chinatown—the scene we see in every Detective Story, where the private eye defends his actions against the dissatisfaction of his employer (in this case Faye Dunaway as Evelyn Mulwray).

“I like my nose. I like breathing through it.”

JAKE GITTES

Okay, go home. But in case you’re interested your husband was murdered. Somebody’s dumping tons of water out of the city reservoirs when we’re supposedly in the middle of a drought. He found out, and he was killed. There’s a waterlogged drunk in the morgue—involuntary manslaughter if anybody wants to take the trouble which they don’t. It looks like half the city is trying to cover it all up, which is fine with me. But, Mrs. Mulwray … I goddam near lost my nose! And I like it. I like breathing through it. And I still think you’re hiding something.

That’s old-school hard-boiled Private Eye lingo. Now here’s the Dude from The Big Lebowski hitting the same beat in the back seat of a stretch limo, confronted by his pissed-off employer, the actual “Big Lebowski”:

DUDE

Look, man, I’ve got certain information … uh … certain things have come to light. Uh … has it ever occurred to you, man, that instead of running around … uh … blaming me. It could be … uh, uh, uh … a lot more complex. It might not be such a … uh … simple … you know? I’ve got information, man. New shit has come to light!

” … information has come to light, man!”

Chinatown was set in 1937 (although it was actually made in 1974.) Lebowski is basically present-day, though it was released in 1998.

Has America changed in those fifty years? Are people different? Have styles-of-being evolved? I daresay we’d have to search long and hard to find a better (or more hysterical) side-by-side comparison than that depicted in these two scenes.

That’s the payoff for us writers when we combine genres. Everything old becomes new. Everything familiar becomes fresh.

Mixing genres works in all fields and almost always produces something interesting. Blend a sports car with a muscle car and you get a Corvette. Mix the same vehicle with a luxury sedan and you get a Porsche Panamera. Combine a panel truck with a car and you get a minivan.

It works just as well with swimsuits and salads and popular music.

Think about using this for your own stuff.

Genre A + Genre Z = New Genre AZ.

July 1, 2016

Insanely Generous

My Terrible Idea!

What decisions did we make to launch Steve’s new book?

Did we actually follow my packaging and marketing principles from my past What it Takes posts?

Despite many missteps, I think we did.

It’s worth a review.

This is a longish article for the diehards, but there is a pretty cool stat as the payoff, so either skip to the end…or bear with the inside publishing baseball and get the how and why behind the insane number of eBooks we gave away the past two weeks.

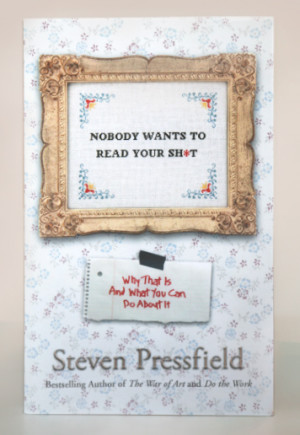

The first and best packaging decision made was…Steve’s….and I loved it straightaway.

He decided to title his new book Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t. It was a title that had been percolating for him since October 2009, when he first explored the notion on this site that writers without empathy for their audience are their own worst enemies.

No-nonsense and cheeky titles like Adam Mansbach’s Go the F*ck to Sleep and Harry G. Frankfurt’s On Bullshit has a strong sales history and my initial reaction when Steve told me his idea was “I Love it! This will be easy!”

There is no arguing with the fact that Steve’s title is provocative…capable of getting a potential buyer to perk up the moment she sees it.

But on closer examination, Steve’s title doesn’t have Mansbach’s funny parental desperation baked into it or the faux academic seriousness of Frankfurt’s. It’s not humor and it’s not sociology…it’s self-help for creatives, a genre that might not be all that keen to hear a harsh profanity flavored truth.

Which posed a serious packaging problem.

The problem was this.

If we published a book called Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t, right from the start we could push away a very large segment of our target readership…writers/artists in the throes of Resistance looking for serious counsel.

They don’t want negative “you’ll never make it” messaging. Who does?

That’s certainly NOT THE THEME OF STEVE’S BOOK, but on first inspection, it would seem to be…

That’s a problem.

We’d already accepted that there are some readers who reject a work that contains profanity from the get-go. Did we want to turn off an even bigger segment? Those people who are more sensitive in terms of their approach to the creative arts?

These kinds of creatives subscribe to the method of getting in touch with one’s deeper self (their inner genius/muse) through reflection and gentle coaxing rather than us blunt blue-collar worker people with salty tongues.

Was our title going to alienate this compelling group of readers?

The answer was “Yes, it probably will.”

Of course most people on the softer side of the unleashing creative power debate would not be turned off by the title if they knew what was inside. If we could get them to read what was inside the book before they bought it…then we’d be home free. Sort of like letting people eat dinner before asking them to pay…

In fact, we were confident that any of those in this camp who were open to giving Steve’s book a try would find themselves gripped by the ideas inside and the narrative approach (a veteran writer confessing his own struggles with the harsh truths of art) so much so that they’d be changed by it.

They’d even embrace the message/s in the book and convince other members of their persuasion to give the book a chance. But they themselves wouldn’t if the title and packaging alienated them so much that they’d never open to page one.

So how could we combat that?

The answer would have to come from 1) adding a subtitle to diffuse the cold hard truth of the title and 2) in the visual packaging of the book. The package would have to yang the yin of the title. It would have to be soft, not harsh…

The subtitle wasn’t that difficult to come up with. Steve and I were on the phone one day thrashing all of this about when we spit-balled a bunch of subtitles. One of us said something like…“This book explains why nobody wants to read anything anymore and more importantly how the writer can change that.”

So that’s how, WHY THAT IS AND WHAT YOU CAN DO ABOUT IT came to be.

We like that subtitle because it makes a promise to skeptical readers that if they give the book a chance, it will explain the harsh point of view of the title and give them the tools necessary to solve the problem.

Okay, so the subtitle was the first step to soften the blow of the title for a potentially large segment of the audience.

Just a quick aside here to point out that Steve and I weren’t packaging the book just for his core audience…we purposefully decided to branch outside our solid core “look.”

We knew that fans of the trilogy The War of Art, Turning Pro, and Do The Work would eventually come to the book no matter what.

They’d read it even if we put the book in a brown paper bag.

The trick to packaging when you have a solid sales track record is to keep your fans fans, of course, which means consistently creating packages of a kind that reinforce the core ethos of the writer. But you also want to make tactical stretching decisions to bring in new members to the tribe.

At some point you just don’t keep preaching to the same choir. You need to go outside of the revival tent and recruit more singers…

With the subtitle figured out, now came the very difficult part of packaging Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t…settling on a vision for the cover art.

Remember my post about how the title and the image should yin and yang? Well, this was the principle that came to be indispensable for our final decision.

The first thing Steve and I did was to call our artist friend Derick Tsai at Magnus Rex. We explained what the book was all about and emailed the manuscript to him and asked him to noodle it around.

Oftentimes Derick nails the image before Steve and I have to even think about it.

Derick’s cover for the Do The Work paperback is a perfect example. We just told him we wanted Do The Work to be of a kind with The War of Art and Turning Pro. About a week after telling him that, he sent us the great idea with the worn down pencil.

Derick’s cover for DO THE WORK

While the artwork is not an in your face contradiction of the title (my whole yin and yang approach was established by The War of Art series sensibility), it is an expression of the core ethos of the trilogy of works.

Plus it implies practicality. Those who wear down their pencils to the nub, aren’t just day-dreaming about being a writer…their writing…

While Derick came up with some interesting visual stuff for Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t, the ideas didn’t quite knock all of our socks off. But what they did do was give us direction.

Derick saw the title and the book itself as a guide to how to “break through the walls” that hold us back from realizing our visions. So he had some cool images of brick walls with outlines of invisible doors that would metaphorically lead the reader into turning the pages of the book.

The idea of the brick wall and the door was terrific, but we just couldn’t make the look of the wall etc. look all that interesting or appealing.

Next up was a terrible idea that I had, but at the time I thought was perfect. It was an image of a selfie-stick with one of those red circles with a line through it–like the one at the top of this post…so sorry again Derick for asking you to mock that up!

For me, one of the most important lessons in Steve’s book is that we can’t fall into the trap of writing all about our own inner and outer dramas…essentially using ourselves as the only drivers of our fiction (or nonfiction for that matter).

These kinds of “me, me, me” works are the equivalent of the selfie-stick photos that are so ubiquitous these days. Does anyone really enjoy looking at someone’s selfie? Unless they’re celebrity selfies that give viewers false senses of intimacy with “important people,” these photos are just plain ridiculous and self-indulgent.

So I thought having an image of a selfie-stick with a line through it, we would tell readers what this book was about…

Unless the writer/artist gives up his selfish need to dramatize his own shit in the hopes that he will be validated by third-party anonymous readers/viewers, he will never create a universal story or work of art. Instead, writers/artists need to empathize with their audiences and craft their works to be so utterly compelling that the reader/viewer projects his/her own life experience into their narrative universe.

Ugh… I think you can see just how difficult it would be to translate that message into a single cover image.

Plus that message is another negative connotation, akin to the title.

NEGATIVE title, NEGATIVE image won’t work for self-help creatives. It will turn people off immediately! Needless to say, the idea blew up. It looked terrible too!

Back to the drawing board.

After about six weeks of flailing, Steve, Derick and I were ready to jump off a cliff. We still had nothing and time was a wasting.

So we went back to basics.

We needed to soften the harsh tone of the title so as not to alienate readers. That was of utmost importance. And,

We also needed to let people know immediately that the book WAS NOT AN OPINION!

It is an unimpeachable and painful truth that has to be dealt with…just like one of those brilliant bits of truths that Ben Franklin was so good at coming up with “neither a borrower nor a lender be….”

Talking this through yet again somehow triggered an idea with Steve.

“This is like one of those things your grandmother would embroider and put on the wall above the kitchen table…” said the former Mad Man.

A sampler…

We all recognized that a warm and cozy grandmotherly sampler was the perfect yang to the yin of the profanity in the title.

So Derick did some mock ups that confirmed that the concept would work, but still there was something just didn’t feel right about the cover.

No matter how many times Derick tried, the texture of the mock up digital sampler just didn’t feel authentic. It looked and felt a bit cynical…exactly the opposite of what we wanted to project…

So we decided to go the full nine yards and actually commissioned a sampler. We’d literally photograph it tacked up on old-timey wallpaper that your grandma may have had up in her very own kitchen.

We turned to Julie Jackson at subversive cross stitch. Not only did she come through with a great design, she even hand-stitched and framed our sampler herself. I bought some old wallpaper from Hannahs Treasures and then I sent the whole shebang to Derick in Los Angeles.

Derick called in a favor from a buddy who owns an art studio and they shot the cover in a day. It looked great!

But we still weren’t finished.

We had to figure out how to handle the back cover copy…

Remember that my previous advice written up in this forum is to get some great quotes?

Well, we decided that Steve’s reputation would be enough to get people interested in this book. Plus the title and cover image were provocative in and of themselves. And if we were to call in a favor to get a famous writer friend to read and give us a front cover blurb for the book…then that favor for this book would be spent and we wouldn’t feel right asking for another from him and here.

So instead of getting quotes…we decided to keep any possible favors from friends for something else. Maybe we wouldn’t even be taking from them…maybe we could give something without a quid pro quo? More on that soon.

So for the back cover, we went with the obvious headline:

FROM THE AUTHOR OF THE WAR OF ART…

The headline immediately triggers to more than 300,000 readers that NWTRYS is “of a kind” with WOA. Keep it simple!

Then we went with a four-sentence set up to intrigue potential readers who’d never heard of The War of Art and for those who have read it, to offer them something fresh.

We followed that up with an excerpt of some meat and potatoes description from of the book itself, to let readers know what drives its argument/s and the kind of narrative voice to expect.

Lastly, Steve recently appeared at a good friend’s conference for creatives and there were some great new photographs of him available…

So we went with a warm and smiley shot (to again counterbalance the inherent negativity of the title) and added a longish version of his author bio. For those unfamiliar with his stuff…to pull them in with his bona fides.

And yet…

We were still concerned about alienating potential readers with that Sh*t in the title. What we needed was to jump-start discussions…we needed a lot of people (my good old 10,000 Reader Rule) to give it a chance so that they could spread the word of mouth necessary to counterbalance resistance people might have to the title.

How could we get word of mouth about the book going in a way that was organic and not heavy handed or cheesy?

This is when we came up with the idea of giving away a free eBook version to as many tribes as possible. This is when we reached out to our friends that we didn’t want to bother asking for advance blurbs.

We’d ask them instead if they’d let their tribes know that we were giving away a free eBook version and point them directly to the place they could download it.

Now the other thing we did to let our friends know that we were “Trojan horsing” them to hook-wink their subscribers to give us their emails so that we could market to them day and night was to decide NOT TO REQUIRE ANYTHING OF ANYONE WISHING TO DOWNLOAD THE BOOK.

We seriously just wanted enough people to read the book early so that we could ensure that the book had the best possible chance of finding a long term audience. The only way to make that clear to everyone was to not make people give up their email addresses to get the free book. It really would be free.

And then we launched.

We first alerted First Look Access Members from www.stevenpressfield.com. Great start!

And then we alerted The Story Grid Subscribers. The momentum built!

We were amazed by the early responses! We hit our 10,000-copy goal in three days!

And then we asked Jonathan Fields, Marie Forleo, Seth Godin, Jeff Goins, Tim Grahl, Eric Handler, Todd Henry, Victoria Labalme, Brett McKay, Mark McGuiness, and Joe Tye to alert their peeps. We worked through their schedules and let it ride.

What happened then is hard to metabolize.

I’m overjoyed to report (as is Steve, Callie and Jeff) that with such insanely generous help from our friends…

In just fifteen days (June 15 through June 30, 2016)…

123,453 people took advantage of the free download!

And judging by the reads and responses to the book, we think we’ve positioned Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t as an evergreen backlist bestseller that will one day join the ranks of The War of Art, Turning Pro, and Do The Work as must-reads for aspiring writers and for all of us pounding out copy professionally too.

Thank you.

June 29, 2016

The Dude Abides … but in What Genre?

[Reminder: only two more days to order your free e-version of my new book on writing, Nobody Wants To Read Your Sh*t. Offer expires at midnight, June 30. Click here to download. Totally free. No opt-in required. Takes 38 seconds or less.]

I was talking three weeks ago about the preparatory files I use before plunging in on a first draft. The first file is one I call Foolscap. Here’s the first question I ask myself in that file:

“What’s the genre?”

The Dude doing his Philip Marlowe thing

I’m asking, “What kind of book am I writing? Is it a Western? A Love Story? What exactly is the genre of this idea I’m working on?”

I ask this first because it’s the most critical question a writer can ask. And because, once I answer it, I’m halfway home.

At this stage (before the first word of a first draft) I may have only the vaguest notion of what my story is. Maybe I’ve got one character, a few scenes, maybe less than that. I’m groping. I’m like the blind man trying to figure out if he’s working with an elephant.

So I ask first, “What’s the genre?”

Why do I ask this? Because genres have conventions. As soon as I identify the kind of story I’m telling, I automatically have a road map, a blueprint for its shape, its trajectory, and its content.

Consider The Big Lebowski by Joel and Ethan Coen.

I have no idea how the brothers evolved their story but I’ll bet anything they started with “the Dude.” They probably even had Jeff Bridges in mind. My guess is they knew the tone of the movie; they knew it would be zany, wry, deadpan. And they knew the feeling of the scenes they wanted. But I’ll bet that, at first, they weren’t sure exactly what genre, what kind of movie it was. Then …

“OMG, it’s a Private Eye Story! It’s a Detective Movie but instead of a having a hard-bitten Sam Spade/Philip Marlowe type as our hero, we’ll have a lovable, slightly-dim stoner.”

Identifying the genre was the stroke that split the diamond. At one blow, the Coen brothers could see the whole movie.

Why? Again, because genres have conventions. A Private Eye Story has obligatory scenes. Every movie or novel in this genre makes stops at these mandatory stations. The audience would be furious if it didn’t.

Next step for the brothers? Cue up Chinatown, The Maltese Falcon, Farewell My Lovely. Watch them or read them with this thought in mind: “What can we steal? What happens to Jack Nicholson, to Bogie, to Robert Mitchum? Whatever that is, we’ll make it happen to the Dude.”

See what I mean about genre?

Once we know what type of story we’re telling, we’ve got half the struggle licked.

But back to Private Eye Stories. What scenes can we count on? What scenes will be in every tale of a gumshoe-for-hire?

He’ll be approached (usually by a rich person) to take on a case.

Halfway through the story, he’ll be hired by another individual (usually intimately connected to the first rich person) to take on an additional case. Both assignments will involve “finding” somebody or some thing.

The hero will become romantically involved with a beautiful woman, usually his client. This liaison will not go well for the hero.

For sure, our detective will get beaten up. Usually more than once.

PHILIP MARLOWE

Moose’s skillet-sized fist hit me. A pool of inky blackness

opened at my feet and I tumbled into it …

Our hero will have a sidekick or partner, possibly a Peter Lorre-type. This cohort will inevitably get our hero into trouble.

There will be scenes of betrayal, duplicity and mistaken identity.

There will be red herrings and multiple plot twists.

In the end, our hero will actually solve the crime. He and no one else. He will come out on top but, alas, without the girl (and perhaps without his fee, his business, or his sanity.)

The Coen brothers knew these conventions. They understood that these were the sinew and marrow of the Detective Story genre.

So the Dude gets hired by the Rich Guy (the actual “Big Lebowski”), then hired again by his daughter Maude, played by Julianne Moore, who indeed will seduce him for her own nefarious purposes. Beat-ups? The Dude will get pummeled by goons, attacked in his bathtub by nihilists, have his White Russian drugged by Ben Gazzara, the porn gangster. His buddy John Goodman will get him into all kinds of trouble. Together they will chase down numerous red herrings, but, in the end, it will be the Dude and only the Dude who cracks the case.

DUDE

She kidnapped herself, man!

My favorite scene in The Big Lebowski is, sure enough, a genre-specific convention: the moment when the hero, in bed with the Beautiful Client, reveals his own (surprisingly profound and emphatically on-theme) backstory. Remember that moment in Chinatown? Jack Nicholson as Jake Gittes is lying back on the pillow, having just made love to Faye Dunaway as Evelyn Mulwray. She asks him how he got into the private detective racket and he tells her he used to “work for the District Attorney” (meaning he was a cop) in L.A.’s Chinatown.

JAKE GITTES

You can’t always tell what’s going on there. I thought

I was keeping someone from being hurt and actually I

ended up making sure they were hurt.

That scene, for sure, was front-of-mind for Joel and Ethan Coen when they put Jeff Bridges in the post-coital sack with Julianne Moore.

MAUDE

Tell me about yourself, Jeffrey.

DUDE

Not much to tell.

(tokes on a joint)

I was one of the authors of

the Port Huron Statement. The original … not the

compromised second draft. Did you hear of the Seattle Seven?

That was me … uh … Music business briefly … roadie for

Metallica. Speed of Sound tour. Bunch of assholes …

Genre conventions are not “formula.” They’re opportunities for tremendous creativity and fun and depth, as the Coen brothers proved in this and a bunch of other movies.

Before you write a word of your first draft, figure out what genre you’re working in. Then bone up on the conventions of that genre and take it from there.

June 15, 2016

Get Steve’s New Book on Writing … Free!

As a thank-you to readers of this blog, we’re giving away the e-version of my newest book, Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t, just out today. No opt-in required. You don’t have to enter your e-mail address or compromise your privacy in any way.

The eBook is free, with no opt-in required.

The book is free, at least for a week or two. (We’re figuring out the offer’s duration as we go along.)

What is Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t about?

The title comes from the first and most important lesson I ever learned as a writer, on the very first day of my very first job, as a junior copywriter for Benton & Bowles Advertising in New York. What the phrase means is that because readers are inevitably busy, impatient, easily-distracted, i.e. they don’t want to read your sh*t, it’s incumbent on you and me as writers to make our stuff so interesting, so sexy, so unusual, so compelling that a reader would have to be crazy NOT to read it.

Every other lesson in writing follows from this one tough-love truth.

Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t is my “lessons learned” from a career in five different writing fields—advertising, screenwriting, fiction, nonfiction, and self-help.

Some sample chapter heads:

Fiction is Truth

Nonfiction is Fiction

Sometimes You Gotta Be Somebody’s Slave

“Steve, Your Ego is Getting Out of Hand,”

Not to mention …

Three-Act Structure

Text and Subtext

How to Write A Boring Memoir

A Non-Story is a Story, and

Sex Scenes.

At the risk of hyping my own stuff, lemme say that Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t is a pretty good from-the-trenches primer for anybody who is a writer already or who has ambitions to become one.

Click here to download your free copy.

And thanks again for sticking with us here on Writing Wednesdays.

June 10, 2016

Write Your Bio (a.k.a. an answer for Michael Beverly)

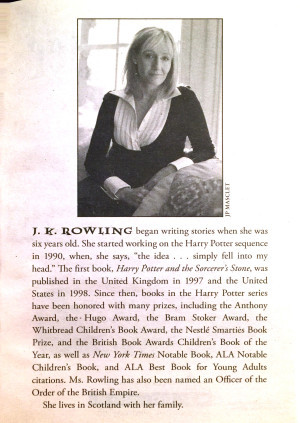

What was her first bio?

In addition to ripping off chunks off Shawn’s work last week, I’ve stolen his spot this week to answer a question from Michael Beverly (See Michael’s full question in last Friday’s comments section.)

Do I think an author bio is necessary for a fiction author?

Necessary? No.

A good idea? Yes.

When I started writing tip-sheet (one-pagers about a book) copy for sales conferences, I learned how much bios play into sales.

The sales reps used these tip sheets to help sell the new season to book buyers.

Without having read the books, the reps would make decisions on which books to emphasize most during sales calls, based on two things: marketing/PR plans and author bios. The reps wanted the first bit because they knew it would grab the buyers’ attention — to confirm sales would be fueled. They wanted the second bit — the bio — to confirm the author had the chops and/or to fuel local sales.

Let’s break down the local and the chops.

For local, the idea was that the sales reps would push local sales if they knew where the authors lived – and that local buyers would be more inclined to buy and feature books by local authors. For established authors, this information wasn’t a must-have, but for first-time/emerging authors, the local angle was one to work. Same holds true today. Sharing where you’re from, where you live, is an opportunity to connect with readers in those communities.

For chops… On the non-fiction front, the sales reps and book buyers wanted credentials that stated why readers would want to buy a specific book from a specific author. For example, for a book about the treatment and prevention of Diabetes, the reps and buyers wanted to know that the author was a doctor who specialized in Diabetes research, treatment and prevention. Why would readers buy that Diabetes book instead of one of the many other books about Diabetes? Well, because it was written by a doc residing at the top of the field.

For fiction, the focus was different. If credentials that fed into the subject of the books were available, they would be used as selling points.

For example, Myke Cole’s bio for his book Gemini Cell is:

As a security contractor, government civilian, and military officer, Myke Cole’s career has run the gamut from counterterrorism to cyber warfare to federal law enforcement. He’s done three tours in Iraq and was recalled to serve during the Deepwater Horizon spill. All that conflict can wear a guy out. Thank goodness for fantasy novels, comic books, late-night games of Dungeons & Dragons, and lots of angst-fueled writing.

If the authors’ day jobs, and/or past experiences, aren’t a fit, their interests hit next. Here’s an example from my kids’ bookshelf:

Erin Hunter is inspired by a love of cats and a fascination with the ferocity of the natural world. As well as having a great respect for nature in all its forms, Erin enjoys creating rich, mythical explanations for animal behavior, shaped by her interest in astrology and standing stones.

*Michael mentioned using a pen name, so I’m hoping he’ll check out Erin Hunter’s site. Erin is actually six different people: Kate Cary, Cherith Baldry, Tui Sutherland, Gillian Philip, Inbali Iserles and Victoria Holmes.

The interest-driven bio is a good approach for the first-time author.

I tried to find J.K. Rowling’s bio for the first edition of Harry Potter online, to see if it mentioned a love of wizards or if it relied on the penniless, divorced mother description than ran in early interviews with her. It would be interesting to know what was in the early bio, to compare it to later editions.

I’d like to know Lauren Weisberger’s bio for the first edition of The Devil Wears Prada, too. The bio in the mass market edition relies on the previous success of the title and features an image from the movie on the cover:

Lauren Weisberger graduated from Cornell University. Her first novel, The Devil Wears Prada, was on the New York Times bestseller list for six months. It has been published in twenty-seven countries. Weisberger lives in New York City.

Another book-to-movie example is from W.P. Kinsella’s book Shoeless Joe, for an edition released after the movie:

W.P. Kinsella is the author of the novel The Iowa Baseball Confederacy and eleven collections of short stories, including Go the Distance. He lives in the Pacific Northwest.

Outside of location, chops and interests, the one other item that authors need for their bios? Their site — or their page on their publisher’s site.

Mike Lupica’s bio, for The Only Game, hits on his career highlights, while also listing his personal web site — and then below the bio are two other sites related to the publisher. A few online options nailed there – and, while a site URL isn’t a biographical description of the author, it does offer an opportunity for readers to learn more elsewhere.

So what to include in bios?

1) Location

2) Interests

3) Credentials

4) Awards

5) Site URL

You might not be able to include all five, but shoot for #1, #2 and #5 — #3 and #4 are icing on the cake.

Here’s the takeaway, Michael: Don’t overthink the bio. Take advantage of the local angle, provide a URL listing where your books can be bought and where more info. about you can be found, and provide a few of your interests. While you don’t have to provide an on-the-fence reader a reason to buy your book, sometimes letting them know you live near them, or have the same interests, is all it takes.

June 8, 2016

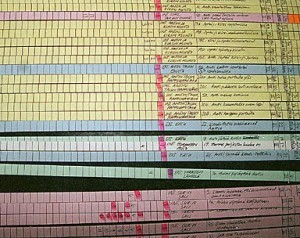

Breakdown Boards

Have you ever seen a “breakdown board” for a movie? You and I as novelists can learn a lot from it about the writing of first drafts.

Breakdown board with sliding panels

Motion pictures, as most of us know, are not shot in sequence. The first day’s filming may be the movie’s final scene, or a scene from the middle of the picture.

What dictates the order of shooting is efficiency.

Budget concerns.

If we’re shooting Zombie Apocalypse VI and we know we’ve got three scenes that take place in the abandoned warehouse down by the railroad tracks, let’s shoot them all back-to-back Monday-Tuesday-Wednesday, even though one is the opening scene, one is a scene from the movie’s middle, and the third is from the climax.

We save money because the production can set up in one location and stay there till that section of the film is in the can. No expensive moves.

Likewise if we’ve managed to convince George Clooney to take a 99% salary cut and appear in five scenes as the deranged high school principal, let’s schedule all his scenes back-to-back as well. That way he can give us three days in a block and then be free to go home.

Can we get him, just for three days?

The breakdown board is the production department’s tool to accomplish this efficiency/economy. The line producer and his or her team start by reading through the screenplay, seeking locations (INT. ABANDONED WAREHOUSE/ZOMBIE HIDEAWAY) that appear more than once. They rip the pages out of the script and stick them all in one place. Those scenes become one sliding panel, i.e. one unified block of shooting time, on the breakdown board

By the time the production team is done deconstructing the script, the sequence-of-scenes-as-story has been turned inside-out and upside-down. But it works in terms of bang for the buck. By filming out of order, we’ve just saved $1.2 million out of our $9 million budget. Maybe we can afford Clooney for an extra half-day.

But back to you and me as novelists slogging through our first drafts.

What law says we have to write in sequence?

Could we gain something by working out of order?

I’m a big believer in this, and my first reason won’t surprise you:

Resistance.

Resistance is the factor that (sometimes, not always) determines for me which scenes and sequences I’ll tackle first.

I want to do the hardest stuff early—meaning the scenes or sequences that will generate the most Resistance. Maybe it’s the climax that’s really, really tough. I can tell because I’m so daunted by it that I don’t even want to face it in outline form. That’s the scene, I know, that I should tackle first, or at least early in the first-draft process.

Remember, the last thing we want to do is save the really hard stuff for the end. (See this post about moving pianos.) What if we spend two years writing our Wordsworth Serial Killer story, get to the finish and find that we can’t make the Climax In the Ruined Bell Tower at Tintern Abbey work?

Write that scene first, or at least outline it, get it to a place where you know you can do it in crunch time and make it work. Force yourself to do this. How good will you feel, going forward, knowing that you’ve got those really tough scenes already in the bank?

There’s another compelling reason to work out of sequence.

The Muse.

Inspiration is not linear. The goddess slings her thunderbolts with no regard to logical story-progression. If I’m working on Page Four but find myself obsessing about a sequence in the middle of the narrative, I’ll drop everything and work on that. It’s great fun, I must say, to reach Act Three and discover, “OMG, I’ve got forty pages that I wrote on this last February and they all work!”

That’s the logic behind writing a first draft out of sequence. It works in the movies. It can work for you and me in books.

That said, there are equally compelling counter-reasons. I confess I often throw the out-of-order concept out the window because of these.

First is story logic. Sometimes it helps to write Scene 41 when you’ve got Scenes 39 and 40 fresh in your mind. Sometimes 39 and 40 trigger great stuff for 41 that we might not have thought of if we’d done 41 in isolation.

Then there’s momentum. Sometimes a story just wants to be told in order. It flows better that way. Its own velocity propels it forward.

Yes, I know. I’m talking out of both sides of my mouth on this issue.

Bottom line: the canny writer uses BOTH techniques. She knows how to roll in-sequence when that feels best. But she’s ready to break that habit and jump around in her story when working out-of-sequence seems to make more sense.

P.S. Don’t steal that Wordsworth Serial Killer idea. That’s mine.

June 3, 2016

Always Be Closing — A Promotional Steal

Finest Kind.

I’m stealing Shawn’s May 27th post — lock, stock and barrel — for this week’s “What It Takes” post.

Last week, Shawn advised readers to “Always Be Closing” when it comes to back cover copy.

Take what he wrote and apply it to promotional copy, whether for pitch letters, e-mails, web site content, or whatever else you’re cookin’.

That book you’re happy with? Don’t kid yourself into thinking the heavy lifting is over. Outreach copy is up next. It might not be as long, but it can sandbag your book.

This is a fundamental mistake (yes, Shawn, I’m stealing…) publicists and authors make again and again. The book is well-written and beautifully packaged, and then launched with half assed promo copy.

A half-ass example I’ve used in the past hit in 2006, following the death of Enron’s Kenneth Lay. Though it was ten years ago, my memory of reading about the pitch is still as clear as if it hit yesterday. Memorable. The pitch was sent to various media outlets, by a publicist who was pitching a book and an author. One of the columnists on the receiving end of the pitch took issue with it and shared it on the pages of BusinessWeek magazine. The following is the beginning of the pitch:

One of the top reasons why CEOs get fired is “Denying Reality.” In milder cases, a CEO will quit rather than let a horrible truth puncture their fantastical views. Or they’ll blame their workers or board. They’ll craft all sorts of psychological defense mechanisms to avoid shouldering culpability.

One could argue in Lay’s case that the truth he would be forced to confront (bankrupt company, displaced workers, destroyed nest eggs, prison, etc.) was so horrible, and so unavoidable, that his body simply shut down rather than confront a terrible reality.

Lay’s death may be the equivalent of a child sticking their fingers in their ears to avoid hearing something bad. But a lot more final.

XXX is CEO of XXXX, a Washington, D.C. based management consulting firm.

XXX has some interesting thoughts on the demise of Ken Lay and how others can avoid his fate.

Please let me know if you would like to speak with him.

Thanks for your time.

The publicist traveled a bridge too far with that copy. Just because you can sometimes force a circle into a square hole doesn’t mean you should.

So what should you write?

1. Keep it simple.

This isn’t the time to show off how many big words you know — or to try to be cutesy or over-the-top, or whatever your thing is. Stick to the facts.

2. Have a tagline at the top.

What’s that one-liner that describes your project? If you followed Shawn’s instructions, you should have it available for your back cover already. Bring it on over to your promo copy. Get that up top and then keep the inverted triangle of copywriting in mind. Important stuff at the top and then info. of decreasing importance toward the bottom.

Still struggling with that tagline? Think about how you’d describe it to a friend. For example, I’ve been recommending A Man Called Ove of late. My tagline for friends: The main character, Ove, is The Odd Couples’ Felix and Oscar rolled into one. Ove has Felix’s sensibilities and heart, mixed with Oscar’s quick wit, unfiltered mouth, and low-tolerance for idiots. The result provides a back-story for that grouchy neighbor we all know, and why he’s so obsessed with HOA rules.

*You might want to go shorter on your tagline, but one thing to pull from the above is that it features examples of people already know. Aim for a tagline that makes it easy to visualize what you’re offering. You can do this by tapping into characters, books, films, etc., with which readers are already familiar. Don’t try to create a new wheel.

3. Get in a short bio.

And by short, I don’t mean a full page. Deep-six your ego and stick to the important bits.

4. Include copy from your book.

Whether your book is fiction or nonfiction, choose specific excerpts. DO NOT send a full chapter. NO ONE is going to read your chapter.

For fiction, pull a short scene or two, such as the following, which appears on the first page, even before the title page, of my worn-out 1970 edition of M*A*S*H:

When the madcap surgeons of the 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) decided to send their houseboy to college, they weren’t going to let money stand in the way . . .

That night they decided to push their luck. The moon was bright, making helicopter flying possible, so the chopper pilots of the Air Rescue Squadron were enlisted. Hawkeye and Duke, with pictures, traveled by Jeep to prearranged points where the troops were in fair quantity. They announced the availability of personally autographed photographs of Jesus Christ, and their timing was perfect. At each point, as the sales talk ended, a brilliant phosphorous flare would be lit, and a helicopter would appear. Spread-eagled on a cross dangling beneath the chopper was the loinclothed, skinny bearded, long-haired and pretty well stoned Trapper John.

Any good act swings. The pictures sold. Back in The Swamp at 1:00 A.M. the loot was counted again. They had six thousand five hundred dollars.

“Let it go at that,” said the Duke. “We got what we needed.”

The packagers of my edition of the book used the story to sell the story. (Still stealing from Shawn… Nice line, isn’t it? “Use the story to sell the story.”)

If I was repping it, I’d pull bits from the pros from Dover section and the football game, too. As Hawkeye would say, I’d feature “finest kind” excerpts rather than chapters.

Thinking of movie trailers might help you with this one. They usually show the good bits, not drawn out scenes. If your book was a film trailer, what clips would you feature?

Same holds true for nonfiction and historical fiction. Pull specific excerpts and tie them to the headlines — without pushing circles into squares.

The following example is another one from 2006, this time related to the release of Steve’ The Afghan Campaign. I created a title for each section, then excerpted a section from the book, which was featured in italics and included the page number on which the excerpt resided. Each excerpt was then followed by a comment from Steve, which tied fiction to fact. Following are two excerpts from the press materials:

The Perpetual Challenge of Afghanistan

The beauty of Afghanistan lies in its distances and its light. The massif of the Hindu Kush, a hundred miles off, looks close enough to touch. But before we get there, hailstones big as sling bullets will ring off our bronze and iron; floods will carry off men and horses we love; the sun will bake us like the bricks of this country’s ten thousand villages. We are as overjoyed to be quit of this place as it is to see us go.

I scoffed, once, at [the god of Afghanistan]. But he has beaten us. Mute, pitiless, remote, Afghanistan’s deity gives up nothing. One appeals to him in vain. Yet he sustains those who call themselves his children, who wring a living from this stony and sterile land.

I have come to fear this god of the Afghans. And that has made me a fighting man, as they are. (page 363)

* * *

Afghanistan is a beautiful, historic, pitiless place. Few have conquered it for long. Alexander is among the greatest military strategists of all time and this place became his strongest challenge. The climate and the land the people come together to make this a bloody and most often regretted battlefield, from Alexander in 300 BC to the Soviet Union almost 2300 years later. And those are but two points on a long timeline. The place changes a little; it is indomitable forever.

“Mission Accomplished” Banner Unfurled Prematurely in Alexander’s Campaign, Too

The fight, he says, will soon be over. All that remains is the pursuit of an enemy who is already on the run and the killing or capturing of commanders who are already beaten. We will be out of here by fall, he pledges, and on to India, whose riches and plunder will dwarf even the vast treasure of Persia. “That said,” Alexander adds, “no foe, however primitive, should be taken lightly, and we shall not commit that error here.” (page 77)

* * *

Alexander’s campaign is rich in lessons for every war effort that followed. Alexander failed to get to India as soon as he expected because the war in Afghanistan refused to end. There are and will always be enemies and campaigns that continue beyond what seems to be the conclusion of major operations. When the follow-up, the sweeping up—the so-called minor operations—stretches from days into weeks, months and years, it dawns on you that “major operations” has more than one definition. What appears to be a loose end can be pulled and pulled until you’ve unraveled a lot of what you’ve done.

Think about what would appeal to you and what would convince you to buy a book. Be honest. Would you really read a five-page, single-line spaced letter, using 8-point type, from a stranger? Don’t lie.

Always be closing — and then steal what you built and apply it to another venture in need of closing.

And: ALWAYS aim for finest kind.

June 1, 2016

“Just Write the Damn Thing!”, Part One

We’ve been talking for the past couple of weeks about first drafts. Bottom line message: Get through them fast and with aggression, even if the final product is imperfect and riddled with TKs (placeholder scenes, descriptions, and dialogue). In other words, “Cover the Canvas.”

Al Pacino knocks ’em dead in “The Godfather.” Before we start, we wanna be sure we’ve got a couple of scenes this good.

That’s fine. It works.

But what do we do before we cover the canvas?

Plunge in blindly? Start writing from Page One?

I’m gonna take the next few weeks to address these questions. What I have to say is purely my own idiosyncratic thinking and experience.

Okay? Here goes …

Before I start a first draft I lay out three files, to which I give the following titles:

1) Foolscap

2) 3Acts

3) 60Scenes

I also start a file called “Theme” and three more titled “Hero,” “Villain,” and “Payoff.” (And a few more that I’ll get into as we go along.)

Why am I doing this? I’m trying to get the story straight in my mind from CHAPTER ONE to THE END. I want a snapshot, a blueprint I can refer to. I’m asking myself, “Is this a good idea? Will anyone want to read this? Is it about something? Does it possess dramatic horsepower? Does it progress from A to Z? Does it pay off in the climax? Do I love it? Can I spend the next two or three years working on it?”

I won’t start the first draft till I can say yes to all those questions (and to a lot of others.)

I won’t start until I can “see the whole movie.”

Did I always work like this? No. For years I dove in on Page One, put my head down and started hammering keys. That’s not always a bad idea. Sometimes it works. But what usually happened for me was I’d get halfway through before it hit me that I was totally lost. Or I’d finish completely only to realize that I basically had to tear the whole house down and start over.

Working in Hollywood taught me to plan ahead. “Screenplays are structure,” William Goldman famously declared. I learned from writing movie scripts to pin sixty index cards to the wall, one for each scene, and to not type a word onto paper till I had those 3X5 cards all working and all in order.

I carry over that same thinking to novels, even though I know from experience that a long-form narrative will morph and evolve wildly over the two or three years it takes to complete it. “It wouldn’t be a plan,” they say in the Marine Corps, “if it didn’t change.”

In the next few weeks I’m gonna get into detail about “Foolscap,” “3Acts,” and “60Scenes.” But for today let’s start with another lesson from the movie biz: Paul Schrader’s theory of pitching.

Paul Schrader is the writer of Taxi Driver and Raging Bull and the director of eighteen movies including Light Sleeper, Affliction, and 2013’s The Canyons. Here’s what he wrote about pitching:

Have a strong early scene, preferably the opening, a clear but simple spine to the story, one or two killer scenes, and a clear sense of the evolution of the main character or central relationship. And an ending. Any more gets in the way.

Paul Schrader was talking (I think) about condensing for presentation a project that was already complete, at least in his mind. He was boiling it down to its pitchable essentials.

I use his technique the opposite way. I ask those questions at the very start, to test my new idea, to see if it might work. In other words, I ask myself Paul Schrader’s questions before I start a first draft.

Do I have a “strong early scene,” i.e. an Inciting Incident?

Does my story have a spine? Can I see a six-lane freeway propelling it from beginning to end?

Do I have at least a few killer scenes? Do I have Michael Corleone gunning down Virgil Sollozzo and Capt. McCluskey at Louis’ restaurant in the Bronx? Do I have the Indominus Rex breaking free and terrorizing thousands at Jurassic World?

Do I have a hero who evolves powerfully from the story’s start to its finish?

And have I got a gangbusters climax? Do Harry and Sally finally get together? Does Matt Damon get back safely from Mars? Does Jay Gatsby’s West Egg mansion devolve into a tragic ruin?

When I can say yes to all these, I’m ready to start putting together a formal Foolscap and to start thinking about “3Acts” and “60Scenes.”

We’re still a long way from “Just Write the Damn Thing!” But we’re getting closer. More on this next week.