Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 72

March 18, 2016

What’s in a Title?

Would you be disappointed if they didn’t serve Margaritas?

[To read more of Shawn’s stuff, visit www.storygrid.com]

Here’s the second in my series of posts about book packaging…

A well known and mostly contented writer I know refuses to reveal the title of his novels before he completes them. He creates no title page for his drafts, nor does he utter the words to confidants until the thing is locked and loaded and already in his publisher’s sales materials. Kind of like the way actors speak of Shakespeare’s Scottish play.

Instead, he gives his novels code names for the files in his computer. If he were Kazuo Ishiguro, his novel The Remains of the Day would be labeled something like Blind Fealty until he’d completed his final editorial draft and sent it forth to the printer.

This writer believes so strongly that to release the title from within and into the external ether, in keystrokes or verbally or God forbid on a Facebook page, would rob it of magic.

Twenty years ago, I thought that was silly. I don’t anymore.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this writer is also the very first one to throw away his tightly guarded title in favor of another one better suited to the work. Even if it’s suggested by someone else. Especially if it’s suggested by someone else.

He’s the first one to scream That’s it!

The reason why this writer holds the title so deep inside himself while he’s crafting the story is that a title can lock you into something that is very difficult to get yourself out of later on.

So the title is a sacred Mantra-like thing to him throughout the writing process, but not so precious that he can’t throw it away after he’s been through several rounds of editing. That takes courage…to be willing to commit to something so religiously and then let it go if it no longer serves the work…

Having witnessed so many writers sabotage themselves with public title obsessions and their subsequent incapacity to separate themselves from their love affair with a phrase, I now embrace this writer’s hard-fought creative wisdom.

A great example of a title almost destroying someone is the odyssey of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Coppola was so overwhelmed by the experience he began referring it to “The Idiodyssey.” Watch the documentary Eleanor Coppola shot and annotated during the 238 days of principal photography Hearts of Darkness and you will witness exactly how the magnitude of that title (John Milius and Michael Herr also wrote drafts and contributed to the screenplay) overwhelmed the production to the point that “little by little we went insane.”

Coppola didn’t have that kind of title pressure when he directed The Godfather or The Godfather Part II. He was an unknown commodity then, interpreting and innovating Mario Puzo’s fresh take on a familiar genre (the Gangster Story).

Apocalypse Now, though– as the title so dramatically expresses–was Coppola’s white whale. It was a project he and his buddies, including Milius and George Lucas, had been kicking around since film school. The ambitions of the work were way, way, way over-the-top. So large that they nearly destroyed him. Literally.

The work that resulted is a masterpiece…a fantastically entertaining Herodotusian action story exploring the darkness inside each and every one of us in the guise of a finger-wagging, anti-war polemic about the very specific and absurd ready, fire, aim American anti-communist Cold War foreign policy… Seriously that’s how broad, deep and yet specifically “of a time” it is.

But I think it’s fair to say that after Apocalypse Now, Coppola hit an Alexander the Great kind of creative wall.

That’s the power of a title.

Okay, so obsession with a title can literally drive an artist crazy.

So let’s just back up a moment now and demystify the thing itself. Can we come to some sort of sensible and practical strategy to create a title before, during or after we write our Story?

First question.

What is the purpose of a title?

Here’s my take.

The purpose of a title is to:

Immediately hook your genre’s readers/viewers.

Make an innovative promise to those readers/viewers.

Bake in the global Story’s theme/controlling idea.

Appeal to as wide of a readership/viewership as possible without alienating the core genre fans.

Create an authorial sensibility (if this is the writer’s first work of fiction or nonfiction) or abide an already established authorial sensibility.

Here I go with GENRE again, right?

Don’t mean to be a grind, but understanding where your Story lives inside the Genre five leaf clover will be immeasurably helpful finding a title that will give your work the very best chance of selling.

Here’s are two examples of titles that I helped create, one fiction and one nonfiction, to give you a sense of what I mean by all of this.

Years ago when I worked at Doubleday publishing, our publisher Steve Rubin asked me to step into his office. Aaron Priest, an agent we both admired who represented some wonderful crime writers, asked Steve if he’s be interested in publishing Robert Crais.

Crais was (and still is!) a darling of the literary crime writing community.

At the time, he’d written seven extremely engaging and successful novels about an L.A. detective named Elvis Cole. He now had a fresh draft of a new novel that he asked Aaron to show around. He was…as they say, “open to editorial suggestions,” which means he was going around town to test the editors out there to see if he could find a fresh editorial/publisher fit.

Steve and I read it overnight and we both loved it.

I had some ideas about how Crais could tweak it a little and give it a broader trajectory, while still remaining faithful to the faithful Cole fans. After a two-hour phone call and one of my silly-long memos, we were both on the same page.

The guy was a pro (still is) and didn’t have any hesitancy to consider new ideas. Even if it meant a month or two more of work. If the idea could strengthen his story, he was like a kid at a carnival. He was also very good at rejecting ideas that didn’t work, too. And I’ll be the first to admit that probably 70% of my solutions to editorial challenges don’t work.

But that’s okay. I make them anyway. My bumblings inevitably poke out better ideas from the writer. That’s why you need to make suggestions as an editor…to goose a fresh neuron to fire inside your writer.

We worked out a deal to publish the book and we were all stoked.

But there was one BIG…BIG…PROBLEM!

A problem Aaron told us about right up front. Crais didn’t like his working title, which as I recall was something like The Devil’s Cantina.

It sounded like a horror novel more than a deep, thoughtful crime novel. Like something Roger Corman would produce and a young Tarantino would direct. Not that there is anything wrong with that.

But that is not what the book was.

People looking for a blood spattered From Dawn to Dusk grotesquerie would be very disappointed by this novel. They’d be all charged up for one kind of experience and the book would give them something else.

Ever order a cheeseburger and have the waiter bring you a BLT?

Hey, nothing wrong with a BLT, right? Probably in the top five of your private favorite sandwich category. But if you were looking forward to a cheeseburger, a BLT is going to disappoint you. No matter how perfectly executed it is.

Same thing with Stories.

Crais had written a wonderful porterhouse steak of a novel, with great sides of creamed spinach, perfectly executed home fries and a rich Cabernet Sauvignon to accompany it. He needed a title to convey that hearty, rib-sticking experience.

With Crais deep into his revisions, the title problem was now all mine.

Let’s go back to my list of things a title should convey.

Immediately hook your genre’s readers/viewers.

So Crais’s laser focused genre was smart Los Angeles based crime writing. And the guy who founded that genre was Raymond Chandler. If I could come up with something that could have been the title of a Raymond Chandler novel, I’d definitely bring in the genre nerds.

Make an innovative promise to those readers/viewers.

I couldn’t just suggest THE BIG SISTER or THE MEDIUM SLEEP and be done with it. Those are obvious rip offs of Chandler and they make no innovation promises to the genre’s fans. What we needed was something that suggested depth and a huge wallop to the solar plexus, a phrase that gives the sense that after the Story has wrapped up…nothing will ever be the same again. We needed to promise a big payoff.

Bake in the global Story’s theme/controlling idea.

A major theme in Crais’s novel was what William Faulkner is famous for saying…“The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” So we needed to convey some sort of haunting of the present by the past in the title.

Appeal to as wide of a readership/viewership as possible without alienating the core genre fans.

This is really tricky. You can’t get too cute with your title and make it so generic that it really means nothing beyond something alliteratively glib–BLOOD BOYS, PAPER PIRATES, COZY CONCUBINES…Help! I’ve thrown a million of those kinds of titles in wastebaskets all over New York.

Here’s a great title that pulls in a global audience while being extremely specific to Genre…Star Wars.

Obvious, right?

Two words and we’re ready for an epic experience set in outer space with a ton of action and combat in ways we can’t even begin to imagine. And because just about every war story has a love story subplot, we even anticipate some kind of romance baked in. And boy does Star Wars deliver on those promises.

So I needed something that said Big Rich Read for this novel, not a phrase that plays as your average fun mystery/crime story.

Create an authorial sensibility (if this is the writer’s first work of fiction or nonfiction) or abide an already established authorial sensibility.

I just couldn’t forget about all of the books Crais had written before this one. I had to come up with a title that “fit” inside his oeuvre. But it also had to promise something unique and “bigger” than what he’d written before. I needed a title that said “breakout book.”

Here are the titles of the novel’s he’d written up to that point:

1. The Monkey’s Raincoat (1987)

Anthony Award winner

Macavity Award winner

Edgar Award nominee

Shamus Award nominee

2. Stalking the Angel (1989)

3. Lullaby Town (1992)

Anthony Award nominee

Shamus Award nominee

4. Free Fall (1993)

Edgar Award nominee

5.Voodoo River (1995)

6. Sunset Express (1996)

Shamus Award winner

Publishers Weekly – Best Books of 1996 selection

7. Indigo Slam (1997)

Shamus Award nominee

I have to tell you that this task really brought me to my knees.

I really couldn’t for the life of me come up with anything that would satisfy all of these requirements. And as these things go, I faced a monster deadline.

We loved Crais’s book so much that we decided to make it our big summer push novel. That is, we were going to go full guns and make a hell of a lot of promises to the retail accounts that we were going to “make this book a bestseller.”

And the only way to position a book as a bestseller is to have a killer package right from the start.

We needed to have a cover and a marketing/advertising/publicity plan that would convince Barnes and Noble to order 15,000 to 20,000 copies of the book in anticipation of very high demand (keep in mind that this was close to twenty years ago and B&N was the monster of the marketplace).

And once B&N came in with a huge buy, we could leverage their enthusiasm with the other retailers (remember Borders?) so that we could get 50,000 to 75,000 hardcover copies straight from the printer to the marketplace. With a saturated distribution, a great title and package, a comprehensive marketing/advertising/publicity program to support the book, we’d deliver a bestseller. (Which in fact we did do).

About two days before the “art meeting” to discuss the packaging of the book, I had to give Bob, Aaron and Steve my title.

For some reason…in my final panicky creative thrashing (Yes the muse makes editorial calls too) a scene from Milos Forman’s adaptation of Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus came to mind.

It’s the ending payoff…Antonio Salieri, played by F. Murray Abraham, is taking musical chart dictation from Mozart (played by Tom Hulce) as he writhes in his bed delirious from infection.

The pathos for the audience is in knowing that the vampiric Salieri (both wildly in love with and viciously loathing of Mozart and his gifts) is desperately trying to suck the last vestiges of genius out of the dying man. And we can’t help but root for Salieri’s success…even as he’s draining the life out of one of God’s chosen ones.

The music he’s trying to get out of Mozart is his Requiem in D Minor, the unfinished masterpiece found in his chambers after his death on December 5, 1791.

Now that’s a word with oomph…Requiem.

So I suggested we call Crais’s new novel L.A. REQUIEM.

Chandler-esque? Check

Big Promise? Check

On Theme? Check

Broad enough to attract non-genre nerds? Check

Fits in with Crais’s other titles? Check

Next up is a story about a nonfiction title.

[To read more of Shawn’s stuff, visit www.storygrid.com]

March 16, 2016

Is Theme Important in Nonfiction too?

[This is the seventh post in our series on Theme. Special thanks to Joe Fontenot, who asked the question above.]

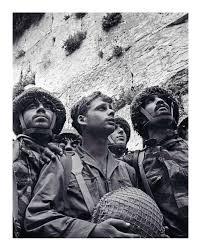

David Rubinger’s iconic photo of Israeli paratroopers at the Western Wall, 7 June 1967.

Answer: Absolutely. Maybe even more so.

Lemme offer an answer based on my own process in structuring and writing The Lion’s Gate.

The Lion’s Gate was published by Sentinel/Penguin in 2014. It’s a narrative nonfiction book about the Arab-Israeli war of 1967—the Six Day War.

Theme was everything in my process, not just in researching and writing the book but also in writing the Book Proposal.

A book proposal is that essential 50-page document that agent and writer (in this case, Shawn and I) submit to deep-pockets publishers, hoping to make a deal with an advance to pay for writing the book.

In other words, theme was critical in this instance not just artistically but financially. It was make-or-break stuff.

Okay …

First, a little historical background so that what follows will make sense:

The Six Day War was a life-and-death clash between Israel and the combined forces of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. It took place between June 5 and June 10, 1967.

The war was initiated by Egypt’s then-president Gamal Abdel Nasser, who in May of that year, in violation of a long-standing UN agreement, began moving tanks (1,000) and troops (100,000) into the Sinai Peninsula, right up to Israel’s southern border. Simultaneously Nasser mounted a fiery rhetorical campaign throughout the Arab world. War was coming, he declared. Its objective was the “elimination of Israel.” Twenty-two Arab nations promised troops, money, and weapons.

Israeli diplomats appealed frantically to their allies—the United States, Britain, and France—for military and political support. Each nation for its own reasons demurred. Israel, outnumbered 40 to 1 by the combined populations of its enemies, appeared to stand at the brink of annihilation. A second Holocaust seemed imminent with the world standing by, doing nothing.

The war began on June 6. Six days later, after furious clashes on three fronts, Israel had destroyed the Egyptian army and air force in their entireties and routed the forces of Jordan and Syria. She had captured the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, and the Old City of Jerusalem.

It was one of the most spectacular David-and-Goliath victories in the history of warfare.

Okay, that’s the historical background. That’s the material and context that I intend to write about.

But what, I’m asking myself, will this book be about?

The answer is not that it’s about the Six Day War.

That’s the subject.

It’s not the theme.

Important: there is no “right answer” to this question. What counts is what theme strikes a chord with the writer. Hundreds of books could be and have been written on the subject of the Six Day War. My question to myself: “What book do I want to write? What theme rings bells for me?”

A book could be written, for instance, whose thrust was, “The Six Day War created the modern Middle East. All the problems we’re facing today came from that war.” (In fact, Michael Oren’s excellent Six Days of War is on exactly that theme.)

Another possible theme could be “The Six Day War produced the rise of Islamism. Nasser’s Arab world was secular. It was only after the defeat in ’67 that Arab nations turned to Islamism as an answer to their problems.”

We could look at the war, from the Israeli side, as a miracle from God. Or as a response to the Holocaust. We could credit Israeli generalship. Or Israeli desperation.

In other words, the number of potential themes on the same subject is limitless.

Again, the question I’m asking myself, long before starting to write, is:

What grabs me about this material? Why has it captured my imagination so powerfully?

I decided that the theme was exile.

Or more precisely, return from exile.

Here was my thinking process:

The iconic image produced by the Six Day War was that of Israeli paratroopers weeping and praying after their capture of the Western Wall. Perhaps you’ve seen the famous David Rubinger photo.

The Western Wall was and is the holiest site of the Jewish people. Jews by tens of thousands make pilgrimages today to visit and pray at this location. The wall itself is the final remnant of Solomon’s temple, which was burnt to the ground by the Romans in 70 A.D. From that date till June 7, 1967 the Jewish people’s most sacred site resided in the hands of others. For nineteen hundred years, no Jew could stand before that wall and say, “This belongs to me. I am free to pray here.”

In other words: exile.

I decided that the theme of my story of the Six Day War would be “return from exile.”

Or, more specifically, “reclaiming the lost soul-center of the people.”

The climax of the story would be the moment the first Israeli paratroopers reached the Western Wall—and their emotional response to this epochal event.

By the way, this statement of theme was central to the book proposal that Shawn, acting as my agent, submitted to Big Five publishers. (The Lion’s Gate, we knew, was too big a book for us to publish at Black Irish.) I was passionate and adamant about this theme of exile. It was the central fixture of the proposal and the primary selling point of the whole project. My pitch was that this theme would be unique, original, and compelling to readers.

Did it work?

Apparently, because a bidding war ensued. In the end, we were able to pay for three years of work.

But let’s get back to Theme from the artistic side. Remember, a few posts ago, we were addressing “levels of theme.” The more levels, we said, the more powerful the theme.

Okay.

We’ve identified the theme of this book we want to write.

What, I’m asking myself now, are the levels of this theme?

Why am I asking this? Because a book or a movie, if it’s going to possess power and emotion, must work on multiple levels. Even if these levels are invisible to the reader or moviegoer, even if they pass right over his or her head, they are still working in the sphere of the unconscious. They give the piece depth and focus and power.

When I’m asking myself, “What are the levels?”, I’m asking, “Does this theme have power? Will this book deliver to the reader a steak-and-potatoes experience?”

Levels of theme.

Let’s start digging.

Level #1, the surface interpretation of the “return from exile/reclaiming the lost soul-center of the people” theme, goes like this:

The Western Wall is literally the soul-center of the Jewish people. Reclaiming it would mean the final and complete end of exile. The children of Israel would, after nearly two millennia of sojourning in the lands of others, finally possess the full measure of nationhood—the ancient territory of Israel and the holiest of its sites. (Before ’67, the Wall was in the hands of the Jordanians and forbidden to Jews.)

That’s Level #1 of the theme.

Let’s dig deeper, reaching for the universal.

Level #2 would take this theme and apply it not just to the Jews but to any people. Putin’s Russia seeking to reconstitute the Soviet sphere by seizing territory in Georgia, Chechnya, the Ukraine. ISIS’s advance into “the caliphate.” The history of Europe from the 16th Century on, including World War I and World War II, is about nothing but the reclaiming by nations of ancient soul-centers.

Let’s go deeper.

Level #3 is that of the individual. You and I. Don’t we too possess a soul-center that we have been in exile from? Our artistic calling that we have never fulfilled? A love we’ve lost? A portion of our manhood or womanhood?

The Gnostics believed that exile was the inherent condition of the human race. Exile from our spiritual center. From our native soul. From the divine.

Let’s go deeper.

Two aspects define the reclaiming of that soul-center, both for a people and for an individual.

First, that soul-center can be reclaimed only by action. Words alone will not produce the personal or people-wide revolution we seek. Nor can that soul-center be given to us by others, however well-intentioned. We have to take it back ourselves, by main force.

Second, the action of reclaiming our soul-center must inevitably be taken in the face of adversity. The dragon will not give up the gold without a fight.

Third, the battle will be life-and-death. Fail and we perish.

Fourth, our sternest adversary will be ourselves. Our own fears and self-limiting beliefs. We must overcome our own faltering hearts before we achieve the redemption and fulfillment we seek.

All four of these factors were true of the Israelis in ’67.

All four have certainly been true of the struggles in my own life and I would wager they’re true universally.

Okay, back to you and me as writers …

We’ve identified our theme.

Now: how does this help us? Is it just an academic exercise or does it pay off in the real world? Will it help us write our book and, if so, how?

First, knowing the theme gives us our climax.

The emotional climax of The Lion’s Gate, we now know, must take place at the Western Wall, when the Israeli paratroopers take control of the Old City of Jerusalem. Somehow we have to structure the book to make the narrative end here.

Second, theme gives us our villains.

There are two. The Arab armies fighting against the Israelis. And the fears and self-doubts of the Israelis themselves.

Third, theme gives us our point of view. (Remember Paddy Chayefsky: “Once I know my theme, I cut everything that is not on-theme.”) Thus every scene in the book must be slanted around the idea of exile, of the “missing piece” of our soul, and of the hopes, fears, and hesitancies around reclaiming it.

Fourth, theme gives us our hero.

Our protagonist will be the Israeli people themselves, specifically the individual warriors, male and female, who fought the war and whom I will find and interview.

You may ask, “Steve, how did you keep these individuals ‘on-theme’ if you were interviewing people you had never met before and you had no idea what stories they would tell you or from what point of view they would tell those stories?”

The answer is I framed my questions around this theme. And, oddly enough, most of the time I didn’t have to do even that. The answers came out spontaneously on-theme.

Specifically:

One helicopter pilot told me of a visit with his younger brother (who happened to be the most decorated officer in the Israeli army) outside the walls of the Old City a few days before the war, in which both brothers expressed their pain at being debarred for so long from access to the Western Wall and from the Old City (both brothers had been born in Jerusalem and grown up there) and their hope that, if war came, they might get the chance to reach this ultimate goal.

Another paratroop captain told me of treks he took throughout his youth to Jerusalem, just to stand at a vantage point outside the city, straining on tiptoe to gain a glimpse not of the Western Wall itself, which could not be seen, but only of a poplar grove that stood above it.

This captain, it turned out, would be the first officer to reach the wall on June 7.

As I was recording these interviews and hearing these stories, I was thinking, “Ah, this is Chapter One!” Or, “This can go right before the climax!”

Fifth, theme gives us our title. (It was Shawn who actually came up with it.)

The Lion’s Gate is a gate in the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. It’s the gate by which the Israeli paratroopers entered on the seventh of June when they reached the Western Wall. A perfect title for a book on this theme.

I hope these personal specifics are not too excessive. My aim is to share my process, for one nonfiction book, and to demonstrate how Theme was absolutely primal and essential to the whole adventure.

To be totally candid it’s possible that I (or another writer) might have structured, researched, and written this book (or any other book) without knowing the theme. I confess I’ve done it before.

But when you do that, you’re operating 100% on instinct. That can work, true. It can work brilliantly.

But then what happens (and I’m speaking from experience) is you write 1500 pages to get 800, because you have to cut so much to reconfigure the book until it’s on-theme. And then you have to whack another 400 pages to make it focused and sharp and lean.

In other words, on a three-year project you can waste an entire year. Worse, such hardship can break your spirit (or your bankroll) and cause you to give up the project entirely.

Start with theme. For fiction or nonfiction. Ask yourself, “Why am I so drawn to this material? What, at its very core, draws me to it?”

That’s your theme.

Take it and run with it.

March 11, 2016

How to Pitch

You have a new book or film or album you want to promote — and you’re waging a letter/e-mail writing campaign to garner support.

The following is what you need to know before you get started.

The Pitch

Bottom line: You want something.

You want to recommend someone or something, or you want someone to recommend you.

You want an endorsement, an interview, a keynote speaker, a job, something for free, someone to make a decision for you.

Start with a thank you:

Thank you for your work.

Thank you for your article “X.”

Thank you for finding a happiness pill.

Thank you for being the only ethical elected official in office.

State your purpose:

I’m writing to request a review copy of your book.

I’m contacting you to ask for your endorsement of my product.

I’m reaching out to you to obtain a bulk discount.

State why you think the recipient of your pitch might be interested:

I read your article titled “X” and thought my book on the same topic would resonate with you.

I’ve read about your service with the Marine Corps and hoped you’d have time to speak with some of the younger men and women of the Corps.

My book is a history of lying politicians, which might add perspective to your coverage of the presidential campaign.

State who you are:

I received the Pulitzer Prize for my coverage of the presidential scandal X.

I’m an 18 year-old student at Y High School. My dad has been sharing your books with me since I was a kid.

Like you, I spent my summers as a caddie. Similar experiences, but I went into business and didn’t commit to writing as early as you did.

State the time, date, address, etc.:

The workshop takes place December 14, 2016, in Hawaii.

I’m available for interviews throughout the campaign cycle.

My address is XXXX

End with a thank you:

Thanks again for your article — and for your time and consideration of my request.

Thanks for your work.

Thanks for _______

Start with a thank you. State your purpose. State why you think “it” would be of interest. State who your are and date/time/address information. Thank the recipient. *Include smooth transitions between each of these. One should run into and relate to the other.

Before you start your letter:

1) Research the individual you’re pitching.

If a health reporter just wrote an article about a 92-year-old, barbell-lifting grandma, he’s not likely to do a follow-up feature on the 92 year-old barbell-lifting grandma you represent, but he might do a piece on what programs work best for specific age groups. You can target something that the reporter showed an interest in, and then suggest an extended conversation.

2) Know the outlet.

Confirm that your project falls into the interest area of the outlet and/or individual you’re approaching. Just because the outlet ran a feature last year, which relates to your subject area today, doesn’t mean they’ll be interested. Same with reporters, which might cover one beat for ten years and then switch to another. Look for current coverage trends to gauge their interest.

3) Consider the placement.

Around the 2000 period, I started pitching military books I repped to features and op-ed sections instead of to book review sections. Military books didn’t receive play in book review sections — and the death of book review sections was on the horizon anyway… Instead of pitching the book, I pitched the person — an expert, who could speak to X, Y and Z, who also happened to be the author of XYZ book. Around the 2004 period, The Atlantic Monthly featured the book The Sling and The Stone in all but one issue within a 12-month period. The book never hit the review section. Instead, the author was interviewed as an expert source for numerous articles, and his book was mentioned every time. Rather than one shot coverage, the author and the book received year-around coverage.

4) Be Ready In Advance.

Watch any of the broadcast news programs and you’ll notice that the experts being interviewed are often authors. This doesn’t make the expert the best person to answer questions about the headline du jour. It makes the expert the one with the fastest publicist and/or the author with materials ready in advance.

For example, there are always more stories related to veterans around November 11th, weight-loss features always hit heavy around January 1st and historical anniversary stories often receive play depending if it is a 50th anniversary vs a 14th anniversary. Then there are the other predictable stories: a politician will be caught with his pants down or his hands in someone’s wallet. A teacher in one location will make a positive breakthrough with students, while a teacher in another area will face jailtime. There will be a blizzard or a drought or a flood, and there will be a recall on one product or another.

Know the news cycles and be ready.

This is harder for fiction, but in some cases it still works. In 2006, around the release of The Afghan Campaign, we placed Steve’s first op-ed. The book was fiction, but the history on which the book was based related to current events.

5) Watch your word count.

If you can’t make your pitch in 300 words, go back to the cutting board.

6) Don’t hide your purpose.

Steve often receives requests that are hidden within blocks of text. The letter below should have started with the interview request and why Steve was being contacted. Instead, it ran on and on about the host.

Dear Mr. Pressfield,

I am reaching out to you on behalf of XXX XXX. XXX is the vice president of XXX as well as a bestselling author and business owner. He has written numerous books with XXX, chairman of the board and co-founder of XXX. Their most recent book, XXX, reached #1 on the Wall Street Journal bestseller list and has been featured on more than 235 bestseller lists including The New York Times and USA Today.

XXX is the host of a monthly webinar which is marketed to our existing database including more than 130,000 XXX associates. XXX itself was recently named the #1 XXX organization in the world across all industries by XXX magazine. In addition, XXX is often invited to speak to corporations and associations around the world regarding XXX. As result, our database/audience is expanding outside of the XXX industry and resonating with the business community.

Given XXX is such a big fan of your book, XXX, and the content aligns with many of the concepts in XXX, he would like to extend an invitation to be his guest on one of our webinars. This would also be a great opportunity for you to promote your work to a large audience. I have included the link to our Website below, which will provide you with access to our webinars if you would like to listen to a sample.

We would be honored to have you as a guest, and if you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Side note: Do not infer that someone will benefit if they work with you unless you can prove it — and guarantee it — in advance. And DON’T tell them what a great opportunity it will be for them. That’s an old — and often brimming-with-bullshit — line. (more on “opportunities” via Jon Acuff).

7) Avoid making demands and trying to make an emergency on your end an emergency on someone else’s end. The following is a recent example:

Hi,

I’m emailing on behalf of Prof. XXX XXX of English at XXX College.

She wants a desk copy of “War of Art” by Steven Pressfield, as she has already adopted the book for an English XXX course, and she needs the book quickly.

Is there more information needed about the course, in order for her to get a desk copy?

Thank you

The writer wants a free book. No, “May I have a copy?” or “Do you provide desk copies?” No please. And: No address.

As a side: Schools tend to place orders late and seem the least in-tune to saving money. The person placing the order will stick to the 7-copy order the professor requested, even though she’d save money if she placed a 10-copy (or more) order, which is when Black Irish Books’ bulk discount kicks in. Seven copies of THE WAR OF ART go for $90.65 at the $12.95 per book cover price. Ten copies go for $58.30 at the $5.83 per book bulk rate.

Here’s another that falls under throwing your looming deadline on someone else:

Should you decide to provide an endorsement, I would be pleased to offer you a gratis copy of the book as a token of our appreciation. If at all possible, we would like to receive the endorsement by November 25th.

The request arrived a month before the deadline, which hit during the holiday season, during which many of us are busy with personal obligations, in addition to our work. Bad timing.

Also: Don’t tell someone you’ll offer a gratis copy in exchange for an endorsement. That’s something that should be a given, an unsaid that’s understood because it is the right thing to do. When the book is released, it should be sent to endorsers with a thank you. And, the manuscript should be sent MONTHS in advance if you’d like someone to consider endorsing it. No one is waiting around for your book to pop up and fill in their time.

8) Don’t go for pity.

This one arrived after we offered the Mega Bundle for Writers last year. The bundle included about $200 worth of books for $35. The package weighed eight pounds, with a $12 shipping charge via FedEx Ground (a charge Black Irish does not mark up).

Dear Black Irish,

Yesterday, used up $47.00 of $47.17 in account with 17 cents remaining, the shipping was a surprise.

Thus If you can throw in the WARRIOR ETHOS with today’s order, that would be extremely appreciated by this starving artist.

Thank you.

If you are a starving artist and have $47.17 left in your account, please use it for food. While books are important, food would be a better choice.

Along these lines, if you’re going to ask for something related to your work, don’t play the pity card. There are millions in this world in need of help. Trying to guilt someone into sharing your product won’t work. You might guilt someone into helping to raise money for a child’s medical bills, or to help rebuild a burnt-down school, but guilt that will result in your personal gain is a long-shot.

9) Don’t misspell names.

We still receive requests for Stephen instead of Steven — and for Pressman instead of Pressfield.

10) Don’t play word games.

In the past year, it seems like everyone contacting Steve about a speaking event is hosting a “summit” or “telesummit.” If you’re holding a meeting or workshop, just call it what it is. Unless a state head is there, summit sounds like the popular term to use, rather than the correct word to use. (As I write this, my daughter is holding a summit in her room with her stuffed animals.)

Your Response to the Response

Whether you receive a yes or a no from someone, write a thank you letter in response. It is one more opportunity to put your name in front of them and forge a connection — and something most of us appreciate.

Two examples:

If you’ve been a long-time reader of this blog, you know that Steve doesn’t do speaking events and he rarely does interviews.

The reality is, if he’s speaking or interviewing, he’s not writing. And, if he’s not writing, he’s not doing the work he was meant to do.

This means we end up sending out a few “no” letters almost every day. Depending on where he is in the world, or at what stage he is with a project, Steve will handle some and I’ll handle the others.

The letters always start with a thank you to the writer, because it was nice that the writer considered Steve as someone to interview, someone to blurb her book, or someone to speak at his event. If the person has said something nice about Steve’s work, I’ll thank the individual for his kind words, or for her thoughts on Steve’s work.

The next line is short and to the point.

Steve is not scheduling speaking events or interviews.

This is followed with a “however.”

However, if you’re interested, Steve would be pleased to donate books for giveaway at your event. While I know this isn’t the same as speaking with him in person, much of what he’d say in person can be found within the pages of his books and/or on his site.

The “however” is an offer to help, though not in the manner requested.

Years ago, I tried to make each of these “no” letters unique. In the interest of time (and having exhausted the options for changing up the letters), they’re all the same, with the exception of the opening thank you addressing the individual’s original letter.

The getting personal part comes during part two, if the letter writer responds.

If the letter writer replies with a thank you, it’s often the start of a long-term connection. I keep track of books sent to them, correspondence and so on. These notes help jump-start my memory when it fails. I’ll remember a name, but not a conversation. After checking my notes I’m on my way again. And if they stay in touch, I respond. Often, I’m still saying no to interviews and speaking events, but if Steve, Shawn or I can help in other ways, we will.

And if you do choose to respond, avoid the actions of a guy Steve wrote about a few years back, in his piece “An Ask Too Far,” which he ended with a retelling of a “No” he gave to someone to whom he’d already given a ton of “Yeses.”

“One guy wrote me out of the blue; I did a long interview for him, wrote a foreword for his book, and even gave him an intro to my agent. Finally he started asking for favors for his friends. This was an ask too far. When I said no, he wrote back: “I always knew you were a Hollywood a*#hole.”

“Dude! I don’t live anywhere near Hollywood.”

Imagine if the guy had responded with a thank you instead — or if he had considered what “no” actually means. Might still be in contact.

In 2013, Seth Godin posted an article titled “What No Means.”

What “no” means

I’m too busy

I don’t trust you

This isn’t on my list

My boss won’t let me

I’m afraid of moving this forward

I’m not the person you think I am

I don’t have the resources you think I do

I’m not the kind of person that does things like this

I don’t want to open the door to a long-term engagement

Thinking about this will cause me to think about other things I just don’t want to deal with

What it doesn’t mean:

I see the world the way you do, I’ve carefully considered every element of this proposal and understand it as well as you do and I hate it and I hate you.

Don’t get offended.

In a spin I did on Seth’s post, I wrote about a post I’d read, from someone I’d told “no.” He made a comment on his site, along the lines of (I’m paraphrasing here):

“Pressfield’s booking person declined an interview with me a while back and, at the time, I bet that if Oprah called, he wouldn’t say no to her. Well . . Guess who did an interview with Oprah?” Then he went on to say he receives books from other authors every day who are interested in working with him and he’ll support them instead . . . (again, paraphrasing, based on my interpretation and memory . . . )

It was painful to read because I understood where he was coming from.

No feels like a personal rejection. He made the no about him. And then he made Steve’s yes to Oprah about him, too. Those answers weren’t about him. They were about Steve, his time and his work.

The Wrap Up

I can’t promise you a “yes” to your pitch, but I can promise you that everything mentioned above has worked the past 20ish years. It hasn’t worked with everyone, but it has worked. Timing often plays the largest role — as have the shifting roles within the media industry. But, you’ve got to start somewhere.

Keep it short.

Keep it to the point.

Keep at it.

March 9, 2016

“Help! I Can’t Find My Theme!”

In space no one can hear you panic

Don’t worry, it happens to me all the time.

It took me ten years to figure out the theme of The Legend of Bagger Vance, and five before I could articulate what Gates of Fire was about.

It’s a running joke between me and Shawn, in his role as my editor, that he’s the one who has to explain my stuff to me. “Oh!” I inevitably exclaim, “so that’s what it’s about.”

Then he gives me eight more pages of things I’ve got to fix because I was flying blind and operating entirely on instinct.

That’s what great editors do. Their gift, their skill is to understand the architecture of story—and then explain it to us dumb-asses who have just deposited six pounds of loose pages on their desks.

I know this sounds like hyperbole. It’s not.

On my third book, Tides of War, Shawn sent me a twenty-eight-page memo (I wish I still had it) that sent me back to the drawing board for an additional nine months.

I didn’t know what the book was about. I had hundreds of pages of off-theme meandering. Dead weight. Fatal baggage. I’d been working on the book for three years but if you’d stopped me and asked the most obvious, fundamental question, the question every writer and artist should be able to answer at once of any work he or she is engaged in — “What is your book/dance/movie about?”—I wouldn’t have been able to answer.

An outside observer might say, “How is this possible? How can a writer compose five hundred or eight hundred pages on a subject and not know what it’s about? That would be like a contractor constructing the George Washington Bridge without plans or even a degree in engineering.”

Yet you and I as writers know how powerful (and how unerring) instinct can sometimes be. We write by feel. By the Muse. By our gut. And sometimes it works. Sometimes it works brilliantly.

As I get older though, I find that more and more I want to know. True, I’m still winging it. But it sure would be handy to have a road map or a checklist. I’d love to be like an airline pilot conferring with his second officer. “Flaps down, check. Oil pressure, check.”

I’d be thrilled to be able, at Page One, to ask myself, “Theme?” and hear myself answer, “Love conquers all” or “Every dog has his day.”

Check.

Got it.

Why, you ask, is it so important for a writer to know her theme? It can’t be that critical if—as you say, Steve—writer after writer finishes his or her book (and they’re good books) without the slightest clue of what its theme is.

The answer is that instinct has its limits.

As airline pilots, we can’t fly by the seat of our pants all the time.

So …

What does knowing our theme give us? How does it help us write our book?

1.Theme tells us who our protagonist is.

The hero, remember, carries the theme.

Rocky.

Jake Gittes.

Fox Mulder.

If we know our theme, we can ask ourselves, “Does our hero in fact embody the theme?” In every scene? In every action? In every line of dialogue?

If he or she doesn’t, we know what we have to fix or cut or rethink entirely.

Theme tells us who our antagonist is.

The villain, we know, carries the counter-theme.

Who, we can now ask ourselves, is the villain in our story? Is it an actual individual? The Alien in Alien? The shark in Jaws? Jeremy Irons or Alan Rickman in anything?

Or is our villain inside our hero’s head? Is it her own arrogance (Out of Africa)? Self-doubt (Joy)? Her belief in something false (Far From Heaven)?

We can ask ourselves of our villain, “Is he or she carrying the counter-theme in every scene, every action, every line of dialogue?” And if he/she isn’t, we can address this and fix it.

NOTE: This wisdom of course is what we hope our editors will give us. But it’s really our job, isn’t it? We can’t just dump a pile of pages on our editors’ desk and hope they’ll save us.

Theme tells us what our climax is.

Hero and Villain, we know, clash in the climax around the issue of the theme. Leonardo DiCaprio and Tom Hardy in The Revenant, Christian Bale and Tom Hardy in The Dark Knight Rises, Matthias Schoenaerts and Tom Hardy in The Drop.)

Knowing this, we can ask ourselves, “Is that what’s truly happening in our climax? If not, why not? And how can we fix it?”

Again, this is why our editors seem so brilliant to us—because they’re asking (and answering) these questions.

Theme can even give us our title.

Breaking Bad, To Have and Have Not, Unforgiven.

Theme influences and determines everything in our story. Mood, setting, tone of voice, narrative device. Theme tells us what clothes to put on our leading lady, what furniture to put in our hero’s house, what type of gun our villain carries strapped to his ankle.

I know it’s hard work. I know it’s not glamorous. But the time we put in, busting our brains trying to answer the question, “What the hell is this story about?” pays off in the end—if only because we don’t have to shout “Help!” to our editors quite as loudly.

March 4, 2016

Critical Questions

Inspired packaging tells a Story

[To read more of Shawn’s stuff, check out www.storygrid.com]

How can you best package your work?

That is, how do you come up with a great title, follow it up with a dynamic idea for a book jacket, and extend the gestalt of the exterior design of the cover into the page-by-page interior design?

And even more importantly, how do you execute the entire vision?

Are there different philosophies when contemplating how to package a hardcover book versus a paperback?

Why? How did they evolve?

Is all of this really that important? If the book is great, no one will care about how it looks, right?

As a publishing nerd with twenty-five years worth of merit (and de-merit) badges to my honor, I’m here to categorically tell you that an inaccurate and misleading package will undermine all of the blood, sweat and tears you’ve put into creating your final draft.

Just as a sloppy suit, unkempt hair and poor personal hygiene will undermine any attempt one makes to gain entrée to the black tied Pen Awards ceremony at Lincoln Center, a poor package for your book will turn away discerning fans of your particular genre.

Remember that fans of your genre are your first readers. And turning them off before they even crack the spine, means no second readers attracted by word of mouth. You’ll never know if what you’ve written has what it takes to become an evergreen bestselling classic in its genre. No one (forget the magic 10,000 number) will give your book a chance. Simply because it doesn’t look authentic…something’s just not quite “right” about it.

It looks like a book someone who has no understanding of its genre cynically designed it in order to trick the widest net of fans possible into believing that it will satisfy them. That “going broad” strategy never works. At least it never has in my experience. You need to package with as much specificity as your write.

If you’re written a steamy romance novel and package it like a crime thriller…you’re in for a world of pain. Crime fans will hate it and steamy romance readers won’t have any idea it even exists.

I suspect the whole packaging problem is what motivates quite a number of writers capable of building their very own profitable publishing businesses from ever even thinking about privately publishing their work.

Do Stephen King or J.K. Rowling need “publishers” to get people to read their work?

Not really. They are already known and reliable brands.

But having publishers allows these titans to concentrate on the words without having to fret over packaging, distribution, etc.

That’s no small relief.

If you already have enough dough in the bank and don’t have to worry about making next months rent, paying a premium to have a traditional publisher take away all of the packaging and publishing hassle can make a lot of sense. But make no mistake. It’s a huge premium. Read this to see just how big.

But what about the rest of us who choose to strike out on our own via Print of Demand technology and eBook distribution? What dangers surround the energy required to package a book properly without a big time publisher’s office and the attendant marketing and art departments to rely on?

What I’ve observed is that for the independent minded, packaging is a process that Resistance exploits to get us to at last break down and succumb to self-sabotage. It couldn’t get us when we were doing the writing, so packaging is its last chance…

Having put the words to the book to bed, packaging is a dangerous gauntlet where the writer/publisher can easily fall prey to Resistance’s final wallop. Utterly exhausted after letting go of our tens of thousands of hard won words, we can find ourselves letting down our guard, half-assing a cover concept, hiring the first graphic designer we can find for the cheapest price possible and agreeing to what they think is “good-enough” treatment.

Just to get the damn thing on sale and out of our lives!

And then when the book doesn’t perform like we had hoped, the writer/publisher puts on the old hair shirt and beats themselves up for writing a bad book. That’s why no one’s buying it, right? Because the ideas and Storytelling are bad.

(Here’s a not so secret, secret…laser focused packaging Trumps bad content. And yes, I intentionally capitalized that verb. So if you have such low self-esteem as to think you’ve written a bunch of dreck or such high self-esteem as to think that your content doesn’t matter as much as your personality…do yourself a favor and double-down on the packaging. It’s working great for the Donald.)

The truth though is that the book could very well be great, but the cover and interior are completely unremarkable or worse, absolutely sending the wrong message. A work that could change people or give them a great deal of joy ends up as land fill or languishes as non-downloaded zeros and ones in some forlorn Amazon server farm in Uzbekistan.

What to do?

Over the next couple of posts, I’ll lay out my idiosyncratic (but I think logical and sound) book packaging philosophy. With greater and greater numbers of writers self-publishing, it just makes sense to share my hard won list of dos and don’ts for making a book as appealing as possible to its target audience.

What? You don’t have a target audience? You better identify one pronto!

Book packaging can be a lot of fun. And it can be extremely painful. Here’s hoping I can increase the frequency of the former and decrease the latter.

In my next post, I’ll cover how I approach the crucial decision that drives all packaging…

What’s the title?

[To read more of Shawn’s stuff, check out www.storygrid.com]

March 2, 2016

Tell Us What Your Story is About

[Continuing our series on Theme in fiction, nonfiction, and movies … ]

I’m a big fan of Blake Snyder. If you haven’t read Save the Cat! and Save the Cat! Goes to the Movies, please rectify that oversight at once.

Bryan Cranston in “Breaking Bad.” The theme is transformation.

One of Blake’s lasting legacies (he died tragically in 2009 at age fifty-one) is what he called BS2, the Blake Snyder Beat Sheet.

The beat sheet is an all-purpose template for writing a screenplay. It breaks down a movie story into fifteen structural beats, e.g. Catalyst, Debate, Break Into Two, Midpoint, All Is Lost, etc.

Number Three, following “Opening Image” and “Setup” is “Theme Stated.”

Here’s what Blake writes in Save the Cat!

Somewhere in the first five minutes of a well-structured screenplay, someone (usually not the main character) will pose a question or make a statement (usually to the main character) that is the theme of the movie. “Be careful what you wish for,” this person will say or “Pride goeth before a fall” or “Family is more important than money.” It won’t be this obvious, it will be conversational, an offhand remark that the main character doesn’t quite get at the moment—but which will have far-reaching and meaningful impact later.

This statement is the movie’s thematic premise.

In When Harry Met Sally, Harry (Billy Crystal) declares right at the top, “It’s impossible for a man and a woman to be friends.” That’s the question. That’s the theme.

The theme of The Imitation Game is stated (the first of three times, each by a different character) first to the protagonist, young Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch), by his best friend and lover Christopher (Jack Bannon) while they’re still schoolboys:

Sometimes it is the people whom no one imagines anything of who do the things that no one can imagine.

That’s a bit “on the nose,” I admit. But it’s the theme (or at least one of them.)

Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing in “The Imitation Game.”

Did you see the pilot for Breaking Bad?

Even if you’ve never watched the series you probably know it’s about mild-mannered high school chemistry teacher Walter White (Bryan Cranston) who gets a diagnosis of inoperable cancer and, to make money to care for his family, embarks upon a life of crime, mainly cooking and dealing methamphetamine, while going farther and farther off the map to become the baddest of the bad, bad, bad guys.

What’s the theme? Did series creator Vince Gilligan state it anywhere, as Blake Snyder suggests?

Indeed there’s a scene right off the bat, while Mr. White is still a law-abiding chem teacher. In class he asks his students, “What is chemistry about?” Several kids offer lame answers. Then our protagonist answers the question himself.

WALTER WHITE

Change. Chemistry is the study of change. Elements combine and change into compounds. That’s all of life, right? Solution, dissolution. Growth. Decay. Transformation. It’s fascinating, really.

This speech is not up front in the pilot by accident. It’s Vince Gilligan’s statement of the series’ theme—transformation.

Here’s more from Blake Snyder:

In many ways a good screenplay is an argument posed by the screenwriter, the pros and cons of living a particular kind of life or pursuing a particular goal. Is a behavior, dream, or goal worth it? What is more important, wealth or happiness? Who is greater in the overall scheme of things—the individual or the group? And the rest of the screenplay is the argument laid out … Whether you’re writing a comedy, a drama, or a sci-fi monster picture, a good movie has to be “about something.” And the place to stick what your movie is about is right up front. Say it! Out loud. Right there.

If you don’t have a movie that’s about something, you’re in trouble. Strive to figure out what you’re trying to say. Maybe you won’t know until the first draft is done. But once you do know, be certain that the subject is raised right up front—page 5 is where I always put it.

But make sure it’s there. It’s your opening bid.

Declare: I can prove it. Then set out to do so.

My own opinion is that, though it’s a neat trick if you can state the theme up front, it’s not imperative. Most of the time the statement goes over everybody’s head except crazed film or fiction buffs anyway.

But what is critically important is that we as writers know the theme ourselves. We should have identified it and be able to articulate it, not vaguely but spot-on. Why? Because we’re the architects of our novel or movie. We have to know the foundation.

Remember Paddy Chayefsky’s axiom:

As soon as I figure out the theme of my play, I type it out in a single sentence and Scotch-tape it to the front of my typewriter. After that, nothing goes into that play that is not on-theme.

February 26, 2016

The Magic of Snow (and Emerging Stories)

This piece hit about this time two years ago. Bringing it back today as the days grow longer and the snow days (hopefully) shorter.

Ezra Jack Keats clipped a strip of four images from Life magazine in 1940. One child. Four endearing expressions and poses.

As the next two decades passed, the little boy in the images remained the same age, with the pursed lips and ballooned cheeks so often worn by children no more than three years old. Bundled up in a long puffy jacket and pants, he lived on Keats’ wall as the artist illustrated one children’s book after another.

In 1962 the child left his static black and white life behind when he woke within the vibrant, adventure-filled pages of The Snowy Day, wondering where the snowball he’d tucked into his pocket the night before had disappeared. The sweetness, innocence, confidence and strength captured within the old images came alive within the book. He’d been given a name, too: Peter.

In 1963 The Snowy Day was awarded the Caldecott Medal.

Finding the Story

There’s a practice in the reality TV world known as “frankenbiting.” Defined by one reality TV editor, frankenbites occur when “you put together one sentence from one answer, another couple words from another answer, another sentence from another day, and make it look like one interview.”

Like reality TV editors, documentary film makers face real people and events. The difference—aside from topic—is found in the editing. Rather than forcing a story—frakenbiting—they help a story emerge. Often, the filmmakers start with one story in mind, only to emerge with another in the end.

In her book Documentary Storytelling, Emmy and Peabody Award-winning filmmaker Sheila Curran Bernard shared:

“In publicity material for the film Sound and Fury, director Josh Aronson says that he initially intended to film five deaf individuals whose experience covered a range of viewpoints on deafness. But in his research, he discovered the Artinians, a family in which two brothers—one hearing, one not—each had a deaf child. This created an opportunity to explore conflict within an extended family over how to raise deaf children. In another example, filmmaker Andrew Jarecki was making a film about birthday party clowns when he discovered, through one of his characters, the story that he eventually told in his documentary, Capturing the Friedmans—that of a family caught up in a devastating child abuse case.”

When Another Story Emerges

According to the Ezra Jack Keats Foundation, Keats didn’t seek children’s books. They found him.

Unable to attend art school despite having received three scholarships, Ezra worked to help support his family and took art classes when he could. Among the jobs he held were mural painter with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and comic book illustrator, most notably at Fawcett Publications, illustrating backgrounds for the Captain Marvel comic strip.

Ezra went into the Army in 1943, and spent the remainder of World War II designing camouflage patterns. After the war, in 1947, he legally changed his name to Ezra Jack Keats, in reaction to the anti-Semitism of the time. It was his own experience of discrimination that deepened his sympathy and understanding for those who suffered similar hardships.

Ezra was determined to study painting in Europe, and in 1949 he spent one very productive season in Paris. . . . After returning to New York, he focused on earning a living as a commercial artist. His illustrations began to appear in publications such as Reader’s Digest, the New York Times Book Review, Collier’s and Playboy, and on the jackets of popular books. . . .

One of his cover illustrations for a novel was on display in a Fifth Avenue bookstore, where it was spotted by the editorial director of Crowell Publishing, Elizabeth Riley. She asked him to work on children’s books for her company, and published his first picture book in 1954. . . . In an unpublished autobiography, Ezra marveled: “I didn’t even ask to get into children’s books.”

Making Sense of the Story

Like the documentarians, Keats pulled together two points from the raw footage of his life—when one story seemed dominate and then another emerged. One, a clipping of a child, and the other, a request for children’s artwork. On their own, not extraordinary—but together . . . From those two points, came a Caldecott Medal award-winning writer and illustrator, whose stories have delighted children—and their teachers and families—for over half a century.

In his Caldecott Medal acceptance speech, Keats said:

Friends would enthusiastically discuss the things they did as children in the snow, others would suggest nuances of plot, or a change of a word. All of us wanted so much to see little Peter march through these pages, experiencing, in the purity and innocence of childhood, the joys of a first snow.

I can honestly say that Peter came into being because we wanted him; and I hope that, as the Scriptures say, “a little child shall lead them,” and that he will show in his own way the wisdom of a pure heart.

Whatever that impulse was to clip the strip from the magazine . . . He didn’t know it was Peter—or even who Peter was—but . . . When he reached that next dot, asked to not just illustrate—but also write—a book . . . That old clipping re-emerged, perhaps like muscle memory of being able to ride a bike after years without a foot on a pedal. Once you feel the balance, you can find it again within a few wobbles. When he started his own book, whatever led him to clip that strip, led him back to it—and thus to the inspiration for Peter in many books to come.

Reexamining the Story

Earlier this week I volunteered in my daughter’s kindergarten class. The Snowy Day met me as I walked in the room. As a child I couldn’t verbalize why I loved it so much. Something about the snow, of knowing what it was to try to keep a snowball overnight in a jacket pocket, of warm baths and a hug from my mother after hours playing in the freezing cold. I didn’t know that adults considered the book groundbreaking, one that some say is the first children’s book to include an African-American child as a hero. I was just happy to sit on the couch with Mom, turning the pages as she read. It wasn’t until years later that time was spent learning of the author.

Just as amazing as the story of Peter’s inspiration is the story of the artwork itself. Also from Keats’ Caldecott acceptance speech:

I had no idea as to how the book would be illustrated, except that I wanted to add a few bits of patterned paper to supplement the painting.

As work progressed, one swatch of material suggested another, and before I realized it, each page was being handled in a style I had never worked in before. A rather strange sequence of events came into play. I worked—and waited. Then quite unexpectedly I would come across just the appropriate material for the page I was working on.

For instance, one day I visited my art supply shop looking for a sheet of off-white paper to use for the bed linen for the opening pages. Before I could make my request, the clerk said, “We just received some wonderful Belgian canvas. I think you’ll like to see it.” I hadn’t painted on canvas for years, but there he was displaying a huge roll of canvas. It had just the right color and texture for the linen. I bought a narrow strip, leaving a puzzled wondering what strange shape of picture I planned to paint.

The creative efforts of people from many lands contributed to the materials in the book. Some of the papers used for the collage came from Japan, some from Italy, some from Sweden, many from our own country.

The mother’s dress is made of the kind of oilcloth used for lining cupboards. I made a big sheet of snow-texture by rolling white paint over wet inks on paper and achieved the effect of snow flakes by cutting patterns out of gum erasers, dipping them into paint, and then stamping them onto the pages. The gray background for the pages where Peter goes to sleep was made by spattering India ink with a toothbrush.

There’s magic in the snow.

Letting the Story Roll

Maya Angelou said, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” The one thing greater is clinging to the wrong story—whether in your book or in your life. I’m glad Keats let his art roll to where it emerged instead of forcing it where he thought he wanted to be.

As I watched the five and six year olds in my daughter’s class paint their own snowmen, I gave up on keeping the paint off of their clothes and the floor and focused instead on the work itself. Keats was right. There’s a magic in snow, especially when it is paired with a child—and there’s an even greater magic in seeing the creativity that emerges.

February 24, 2016

The Truth is Out There

As writers we want a big theme. A theme with power and scale.

David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson. The truth is out there — on at least six levels.

But, even more, we want a theme with depth, a theme that has level after level of meaning.

The theme in Jurassic World, we said last week, is “Don’t mess with Mother Nature.” Let’s examine how deep that theme goes. How many levels does it work on?

On the surface, on Level #1, what Jurassic’s theme means is “Don’t resurrect and genetically mutate creatures with very large teeth and extremely aggressive carnivorous instincts—and, if you do, pen them up very, very securely.”

Level #2 of the same theme is “Arrogance produces calamity.” Pride goeth before the fall, or, as the ancient Greeks would’ve said, “Hubris produces Nemesis.”

This second level takes the theme significantly beyond dinosaurs and theme parks. It could be speaking of the U.S. invasion of Iraq. It could have resonance with global climate change and mankind’s contribution to it.

Level #3 goes even deeper. On the spiritual level, “Don’t mess with Mother Nature” becomes, “There exists a proper relationship between the human and the divine. Heed, O Man, and transgress not.”

Readers and audiences feel these levels, even if they can’t articulate them. Even if they’re completely unconscious of these layers of meaning, the audience senses the depth of the material (yes, even in a dino flick) and this adds to the emotional wallop of the story.

Worldwide, the four Jurassic Park movies have made $3.5 billion. Yeah, the rush of watching dinosaurs on a rampage may account for 90% of that. But depth of theme is contributing too. It helps.

Consider another runaway hit: The X-Files.

What is The X-Files about? We could say it’s about the search for extraterrestrial invaders, or about the relationship between Scully and Mulder. That would be the subject, but it’s not the theme.

The theme is conspiracy—and paranoia spawned by the fear of conspiracy. The ad line says it all:

The Truth is Out There.

That theme is much bigger than the content of the X-Files show or movies, and it resonates for the viewer at a far deeper level.

Level #1 is personal. It’s Mulder’s (David Duchovny) individual paranoia and belief in conspiracy. His sister vanished when he was a child. He’s convinced she was abducted by aliens, but he can’t get anyone in authority to believe him or to take his conviction seriously.

Level #2 is the political. Aliens have indeed landed (or crashed) on Earth many times. The government has evidence of this but, for its own nefarious reasons, is keeping it secret from the public.

Now we’re getting into juicy paranoia and conspiracy. Let’s go deeper.

Level #3 is the darker political. Beyond its knowledge of UFO crashes and alien apprehensions, the government is covering up all kinds of evil truths and events. Who killed Kennedy? Why did we go to war in Vietnam? What forces lurk behind the Wall Street cabal?

Level #4: Authority in all forms is hiding stuff from us. Our parents. Our schools. Our institutions. The world is not as we have been told it is (it’s worse … and we’re getting screwed by it big-time!)—and no one in authority will break silence to confirm this.

This sounds nuts, I know. But why are survivalists stocking up on beef jerky and .762 ammo? Why did gun-toting ranchers occupy Malheur Reserve in Oregon? In Texas the governor put the State Guard on alert just this past summer, fearing that an army training exercise was really a cover for the Feds to take over the state. On the left, the paranoia runs just as deep. Doesn’t the Trilateral Commission secretly control the universe? Or is that Fox News and the “vast right-wing conspiracy?”

Let’s dig even deeper.

Level #5: Our very conception of reality has been manipulated to render us passive and to control us. You and I are like the characters in 1984 or The Matrix. Unseen overlords have created an artificial environment and convinced us that it is real. They are duping us and exploiting us for their own profit.

Level #6: Life itself, by its very nature, is an illusion. More than that, built in to the nature of consciousness are factors invisible to us whose sole purpose is to make us believe in the reality of this surface illusion. A man has a dream in which he is a butterfly. Is he a man dreaming he’s a butterfly—or a butterfly dreaming he’s a man?

The truth is indeed out there, but we can’t get to it. “Help!”

But wait, there’s more!

The X-Files has a second prominent ad line:

I Want To Believe

Implicit in this line is Level #7: the Truth that is “out there” is indeed being hidden from us by corrupt, evil forces but, brothers and sisters, what if we could actually find out that truth? It could change our lives! Save our lives! You bet we want to believe!

The surface interpretation of Level #7 is, “We want to believe in UFOs and aliens, that they’ve visited the Earth and that we are not alone. Perhaps contact with their advanced intelligence will bring blessings to mankind.”

Beyond that (Level #8) is, “We want to believe that some higher power/consciousness exists and that we can contact it.” We want to believe because that truth, if it were true, would reassure us that our lives were not limited to the vain, petty, self-interested issues that consume our daily worlds. We want to believe in something greater, wiser, more significant—something that will give our lives true meaning.

How potent is this level? It’s the basis for every religion since animism and sun worship. No wonder people follow the adventures of Scully and Mulder. Their quest is resonating on at least eight levels.

The X-Files, if you’ve ever watched it, is not that great a show. But the theme is so big and it resonates at so many levels that millions of viewers became hopelessly addicted. They couldn’t live without it.

With all due respect to David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson (and hats off to Chris Carter, who created the show), this is the power of theme.

The bigger the theme, the more forceful the story’s impact. And the deeper the theme (that is, the more levels on which it resonates), the more it will get its hooks into the audience and the more powerfully it will bind them to the characters and to the story.

February 19, 2016

Literary and Commercial

Five years ago, Steve, Callie, Jeff and I were in the throws of marketing Steve’s novel THE PROFESSION. In order to attract more people to Steve’s work, and this website, we decided to launch a series of posts called WHAT IT TAKES, with Callie and I trading off on our theories about what it takes to publish and market a book in today’s brave new publishing world.

As I’m on my annual goof-off at the beach, I thought it would be fun to revisit one of those early posts. And guess what? Things haven’t really changed all that much… There are still two publishing cultures…and you better know which one your world falls under, or you’ll have a very difficult time finding a tribe of readers to follow you.

If you are a publisher or an editor today in traditional trade book publishing, you have to decide which of the two cultures you want to align yourself with.

The “literary” culture is represented by these publishers: Knopf, FSG, Scribner, Random House, Riverhead, Penguin Press and a number of other houses both independent and corporate owned. These houses are known for the high end literary stuff—Cormac McCarthy, Toni Morrison, Jonathan Franzen, Richard Powers, Zadie Smith, Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon, etc.

Young English Lit grad editorial assistant wannabes long to land a job at one of these houses. Working at these shops gives entrée to Paris Review parties and publishing street cred that says “I’m in it for the right reasons…to nurture tomorrow’s great American novelists.” Acquiring a writer who ends up on The New Yorker’s 20 under 40 can get you a promotion. A rave in The New York Review of Books or The Atlantic puts a swagger in your step.

On the other side of the street is the “commercial” culture, often referred to as genre fiction (even though every great story abides by genre conventions). Future editors in the commercial arena are the nerds you see reading The Hobbit, The Da Vinci Code, Jaws, Twilight, Lace or Dune on the beach while the other kids are body surfing. They often come from that wonderful crop of college graduates who don’t know what to do with their lives so decide to find work that pays them to read. They don’t care so much about line by line writing perfection, deep universal truths, or post-modern metafiction pyrotechnics, these editors are just addicted to narrative velocity—stories that grab you by the throat and won’t let you go.

At the top of “commercial” pyramid is Women’s fiction—big bestselling books like The Help, The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, etc. Women’s fiction doesn’t mean that male writers are excluded from the category. But rather that the books written by men must have themes, characters, or plotlines that women enjoy. They scale.

Estimates reach as high as 70% of the entire book buying market being women. So in order to really hit a book out of the park, a writer/publisher needs to bring women to the party. The male writers that do count women as devoted readers write stories that often include a love story within their overarching plot. Nicholas Sparks is a terrific example of a male writer embraced by a female audience.

Male writers with female readers also feature strong female characters in their novels. Stieg Larsson’s GIRL… thrillers are an example. So too are works by James Patterson, John Grisham, Pat Conroy, David Baldacci, and Dan Brown. These guys are not seen as “boys’ book” writers. They have BIG crossover appeal.

What constitutes a “boy book?” Boy books are those commercial categories that are purely male themed—military thrillers, sports novels etc. While it’s true that women dominate the book buying market, men tend to buy what I like to think of as “statement” books. They buy Tom Clancy, Vince Flynn, Brad Thor. They buy Robert Ludlum (Ludlum, when he was alive, was a boy book writer before Matt Damon put a sympathetic face to Jason Bourne and made the Bourne books women friendly). They buy Steven Pressfield. These are books that are on display in their home libraries.

It is true that male readers are harder to reach, but once you get their attention and they enjoy what they’ve read, you usually have a dedicated fan who will buy that author’s next book and the book after that book. That’s not always the case with breakout Women’s fiction writers…there is a phenomenon known as “Second Novelitis” that continues to haunt the industry.

If boy books, like Steve’s The Profession , are harder to scale, how might one even try?

, are harder to scale, how might one even try?

It’s worth going deeper into what Random House sales rep David Glenn advised at the end of his interview in Selling Books in the Trenches:

Talent and desire aren’t enough to make the registers ring at retail. For that, you need to have identified your audience and have written your book in such a way as to give them the reason, or “hook,” to buy it…Ultimately, who’s the target, and why?