Surviving in the Desert

A few years ago I wrote a book called Killing Rommel. Killing Rommel is a novel set during WWII in the North Africa campaign. Its heroes are the men of the Long Range Desert Group, a true historical British commando unit that fought behind the lines against Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and the German Afrika Korps.

Kiwis and Brits of the Long Range Desert Group

The first time I heard the name Long Range Desert Group, I fell in love with it. I said to myself, “I don’t know what this is, but I gotta write a book about it.”

“Long Range.” Way cooler that Short Range.

Even better: “Long Range Desert.” Somebody was going out into the Tall Sand a long, long way.

And “Long Range Desert Group?” It didn’t sound typically military to me. It sounded like a tech start-up.

The LRDG, it turned out, smacked more of a civilian outfit than an over-organized, rigorously-disciplined military team. The trucks they drove were Chevy “30-hundredweights,” bought from civvie dealerships in Cairo. Discipline was slack. Improvisation was the order of the day.

Why did I love this subject?

Because it reminded me of the writer’s life.

The men of the LRDG had a mission. Their charge was to leave civilization behind and advance alone into the unknown. Once out there, they could call on no one for aid or rescue. They were on their own, with nothing to assure their success except what they brought with them.

That’s you and me. That’s the writer’s life.

The desert is a metaphor for the creative sphere that you and I operate in. The desert is beautiful. It’s remote, it’s odd, it’s strange. Only a special few dare to enter.

The desert contains secrets. It’s mysterious; it seems barren but it’s actually teeming with life if you know where to look.

The “sand sea” of the Libyan desert

The desert is reality stripped to its essentials. It’s pure. It’s geometric. Its landscape of dunes and wadis (dry rivercourses) has been shaped by nothing but the elemental forces of wind, water, and time.

The desert is cruel. It will cook you, freeze you, drown you. Worse, the desert is indifferent. Its sand will drift over your corpse in minutes. It will forget you as if you never existed.

That’s our world, yours and mine. It’s the dimension we enter every day, seeking our Muse.

What about enemies?

The desert holds two—the external foe (in the case of the Long Range Desert Group, the enemy was the Afrika Korps) and the internal adversary, the men’s own fears and Resistance.

Think about it. Your truck breaks down five hundred miles from civilization. By noon, external temperature will hit 130 Fahrenheit. Can you keep your head? Can you improvise a fix for your cracked engine block? Can you stretch twenty gallons of fuel to carry you home?

That’s you and me at page 183 in our novel. That’s us in the middle at Act Two.

What I love too about the Long Range Desert Group (and why it fits into this series on the Professional Mindset) as that it was—and had to be, by the nature of its mission and the grounds over which it operated—self-contained.

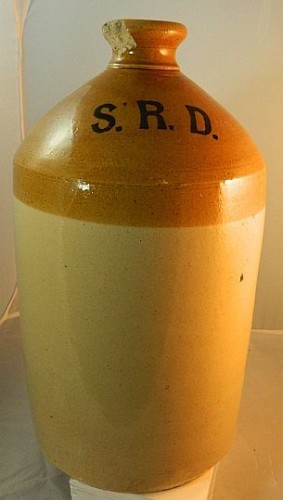

Into the beds of those Chevy trucks the men of the LRDG loaded fuel, water, rations, radio gear, weapons, ammunition, spare parts. Into nooks and crannies they wedged their bedding and clothing, their tea and tins of bully beef. Like sailors they brought rum, in porcelain demijohns jars labeled S.R.D. (for Service Reserve Depot) that they translated as “Seldom Reaches Destination.”

A ceramic or porcelain demijohn held one Imperial gallon (4.5 liters) of rum.

That’s you and me too. The essence of our artistic/entrepreneurial life is that it is and must be self-contained.

We and we alone must decide what we will work on, and how, for how long, under what conditions, with what ambitions and aspirations. We have to master the art of self-evaluation. Is our idea good? Good enough to give two years of our lives to?

When our vehicle founders in the Sand Sea, what resources can we call on within ourselves? The cavalry isn’t coming. It’s up to us and us alone.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Long Range Desert Group was the type of men it sought for its ranks. The LRDG never lacked for volunteers. Out of one application-round of 800 men, it selected twelve.

Most of the men in the Long Range Desert Group were Kiwis. New Zealanders. They were farmers and stockmen, mechanics and farm appraisers. Their age was roughly ten years older than regular line troops. Most were married and had children. No few owned and worked farms and ranches of considerable size.

They were mature men (alas, no women went into the desert in that era, though that almost certainly would be different today) whose primary emotional characteristics were resourcefulness, level-headedness, self-composure, patience, the ability to work in close quarters with others, the capacity to endure adversity and even to thrive on it, and, not least, the possession of a sense of humor.

In other words they weren’t blood-and-guts man-killers. (Okay, some were.) They were cool customers, possessed of grit and savvy, who could embark on a mission whose hazard was such that saner heads would call it absolutely nuts—and see that mission through, no matter what .

Isn’t it interesting that those are the same qualities you and I need, to survive in our own inner deserts?