Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 59

June 23, 2017

The Magic Pill

[Today’s “What It Takes” is from the vault, coming to you via July 24, 2015]

If there is one question that I get asked again and again and again, it’s this:

Until these guys win the inner war for us, we're useless

Is there a resource available that lists all of the conventions and obligatory scenes of each and every genre?

The short answer to this is “not that I’m aware of.”

I have a theory about why we all want such a Story “cheat sheet” which I’ll get into later.

But I can absolutely understand why ambitious writers at the start of their careers (and those who’ve been mining the Micro worlds of writing for their respective 10,000 hours too) would appreciate such a resource.

After all, understanding and applying the Macro principles of writing (part of which are genres conventions and obligatory scenes) is one of the things that Steve Pressfield and I keep harping on. The thing that took him from “doesn’t work” to “works.” That whole Foolscap Method thing.

Figuring out the Macro movements of Story took Steve from polished line-by-line writer with no income (except when he toiled off and on as a Mad Man to fill his coffers) to a published novelist and nonfiction writer capable of earning enough cash to pay his electric bill.

Isn’t that the goal? Being an artist with a big enough audience to create stuff as a full time job? Not a million copy audience. Just one large enough to keep the wolf from the door?

For Story Nerds, that is absolutely the goal.

It’s a destination that gives me a level of focus when darkness descends and the black dogs of doubt howl.

I still have to edit other people’s work and publish other people’s books and agent other people’s projects to keep my household afloat.

Don’t get me wrong. I love doing that too, but come on? Why do I bang out thousands of words a week at Storygrid and here?

Because it’s important work even if my writing is a red line item on my bank ledger. Especially because I have to “pay” for it.

Huh? Aren’t I an idiot for writing a bunch of stuff that actually takes currency out of my family’s cookie jar?

Well, that’s the definition of important work. When you put more into something than it “gives back,” it’s important.

As Steve points out in The War of Art and Turning Pro and Do the Work and in all of his fiction, you need to seek out those places in your life where you are giving more than you seem to be getting. They’re the places to put your surplus (if not all) of your energy.

You’re here for a reason…that reason is to put more into something than it gives back, right? It would be cool to leave the earth a better place than when you got here, wouldn’t it? Well that requires giving more than you get.

So all of you out there who email me pissed off about how you’ve been at it for ten years with double digits of material and claim that you still have bupkis to show for it, spare me. Send me another email in fifteen years bitching about the same thing and we can have a cup of coffee.

Don’t kid yourself.

Those “wasted years,” those unpublished manuscripts…they are priceless. Deep down, you know that they are as well as I do. You don’t write for 3rd Party Validation. You never have. You write because you have to. You’d be in some rehab center or in the ground if you didn’t.

So enough with the “when will Random House bring me into the circle?” and “how do I get people to read my stuff?” questions. You don’t put your ass in the chair every day to get those answers. So stop asking those questions and keep plumbing the mystery.

Think of the poor suckers who have nothing to drive them to such despair…pity them, not yourself. You’ve got the great universe of Story pushing you.

But what about my theory? Why do people want the answers to Genre’s big questions all neat and tidy in a single resource?

What a compendium of conventions and obligatory scenes speaks to is the “magic pill” desire in us all. Hell…I’d love to take a look at that tome myself. I’d buy the first copy.

But it would do me no good if I don’t know how to use it.

Three years ago I fell in love with a set of bedside tables. They were of simple design and just perfect. But the antique dealer (junk shop) wanted like $2000 for the pair. Crazy, right?

I muttered to myself and left that shop determined to make my own. But not before taking about fifty photographs of them. Front/back/side/underneath etc. Took measurements too.

I then went online and found a great woodworking site that offered to sell me everything I’d need to reproduce those puppies. I bought the dovetailer. The precision router. The micro sander. I spent far too much money on the tools, but I figured I’d make up for it with all of the great stuff I’d be able to make.

You know how this ends.

I spent a good 300 hours trying to recreate those “simple” nightstands. And I look at them every day. They’re in a pile of crap I keep meaning to finish right next to my writing desk.

Weird right? I have the answers to creating the perfect nightstands (the tools and the measurements). But what I don’t have the woodworker’s craft yet. So I can’t use the answers all that well.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with putting together what everyone is asking for. Just like there is nothing wrong with created a newfangled dovetailer. And if I live long enough, I’ll do my best to make as big of a dent as I can in the considerable amount of work it will take to create the resource. I’ve been working up the conventions for the Redemption/Performance genre over at storygrid the last couple of weeks.

But the answers will only really help those obsessed with the questions—those who’ve put in exponentially more work hours into learning Story’s craft than I have learning how to dovetail.

When we’re sick, we want that pill that’s going to make us better as soon as possible. We want the vile microbes in our bodies to be vanquished with one swallow or one shot.

We don’t want to lie in bed for three days sweating out a fever.

It’s uncomfortable and tedious and disorienting to break our day-to-day routines to just lie there headache-y and sniffling, waiting for our good guy antibodies to wipe out the invading microbial hoards.

No matter. We can bitch and moan all we want, but our insides have to do the hidden work before we can stand up again and face the external world with purpose and vigor.

The inner war must be fought first before we can effectively face the reality of the external world. Sure we can mask the symptoms with Sudafed and Nyquil, but none of us is worth a damn on that stuff.

There is no magic pill. Just the inner war.

[Join www.storygrid.com to read more of Shawn’s Stuff]

June 21, 2017

Elements of a Great Villain

The shark in Jaws first surfaced in Peter Benchley’s novel in 1974. It’s still scaring the crap out of swimmers from Jones Beach to the Banzai Pipeline. The Alien first burst from John Hurt’s chest in 1979. The Terminator landed in 1984. And how about the Furies (Part Three of Aeschylus’s Oresteia) from 458 BCE?

John Hurt having a bad moment in the 1979 “Alien”

What qualities do these Hall of Fame antagonists have in common?

They cannot be reasoned with (Okay, the Furies did have a bit of a soft spot).

They cannot be appealed to on the basis of justice, fair play, or the idea of right and wrong.

They are internally, relentlessly driven to achieve their ends. Nothing can stop them except their own annihilation.

Their intention is the destruction of the hero.

MATT HOOPER (RICHARD DREYFUSS)

What we are dealing with here is a perfect engine, an eating machine that is a miracle of evolution. It swims and eats and makes little baby sharks, that’s it.

Why is the Thing such a terrifying villain, or the pod people in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or the nuclear-mutated ants in Them?

KYLE REESE (MICHAEL BIEHN)

Listen, and understand! That Terminator is out there! It can’t be bargained with. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop …ever, until you are dead!

Linda Hamilton and Michael Biehn on the run in “The Terminator”

So far these examples are all external villains. They exist in physical form. Their province lies outside the hero’s mind.

What about antagonists who reside inside the hero’s head?

Even they, even great societal and internal villains, share the qualities listed above.

Racism in Huckleberry Finn, Beloved, and The Help.

Greed in Wall Street, Margin Call and Bonfire of the Vanities.

JOHN TULD (JEREMY IRONS)

What have I told you since the first day you stepped into my office? There are three ways to make a living in this business. Be first, be smarter, or cheat. Now I don’t cheat. And although I like to think we have some pretty smart people in this building, it sure is a helluva lot easier to just be first.

JARED COHEN (SIMON BAKER)

Sell it all. Today.

Jeremy Irons tells it like it is in “Margin Call”

Ahab’s rage for vengeance in Moby Dick is an internal villain. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel remorse, or pity, or fear. And it will not stop until it has killed its enemy or its host.

The insanity of war in Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, and All Quiet on the Western Front.

Jay Gatsby’s belief that he can recreate the past.

All these villains are relentless, indefatigable forces that heed no warnings, respond to no appeals, and will not stop until they themselves are destroyed.

A villain can be human. A villain should be human. He or she should have quirks and weaknesses and internal contradictions, like all of us.

But for you and me as writers, if we’re going to get down on paper a really memorable Bad Dude or Dudette, we’d better make sure that that villain passes muster on Points One to Four above.

June 15, 2017

Thank You General Sam

(In 2010 we ran the interview below with General Samuel Vaughan Wilson. In the years that followed, I found myself sitting on General Sam’s front porch, listening to his stories and wandering through the fields and woods surrounding his home. His obituary in the Washington Post this past week shared highlights of his military and intel career. While I spent days listening to stories from those periods of his life, to me he will always be more teacher than soldier or “spymaster.” He believed in, and devoted his life to, his country, and then gave every lesson he learned to the generations that followed. I was never surprised to find people, particularly previous students from Hampden-Sydney College dropping in unannounced. He taught through story, something we talk about here all the time. In his case he had some extraordinary stories to tell, all with lessons of leadership and hard work, and doing what’s right over what’s easy. He also cared. He gave so much of his life to others. I’m blessed to have been gifted even a minute of that life. I miss him, but I see him clear as day in my memory. He’ll always be on his front porch, sitting in his rocker, with his beloved German Shepherd Max at his side. His work isn’t done – it’s simply in the care of others. Thank you General Sam. ~Callie)

General Sam Wilson has accomplished more in his lifetime than many of us dare to dream about. He served as a reconnaissance officer with Merrill’s Marauders in Burma, during WWII; as a CIA spy-ring operator in Berlin, uncovering Soviet secrets; as a director of instruction at the U.S. Army Special Warfare School; as a civilian working with USAID in Vietnam and then in the personal rank of minister at the U.S. Embassy in Saigon; and then back in the military, as a Special Forces Group Commander, followed by an assignment as the Assistant Commandant at the U.S. Army’s JFK Institute for Military Assistance (now the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare School); then Assistant Division Commander for Operations in the 82nd Airborne Division; as chief defense attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow; as a director of the Defense Intelligence Agency; as Deputy to the Director Central Intelligence for the Intelligence Community; as one of the founders of the U.S. Special Operations forces and one of the creators of the Army’s Delta Force; and as a teacher and ultimately president of Hampden-Sydney College.

SP: One of the questions that I’ve been asked as a writer, and which I’ve asked others is: Where do your ideas come from? Often, people say that their ideas come via experiences leading them to a certain point, or a Muse or other source. When I read about your career—that you joined the military at 16, and that you were teaching counter-insurgency by 19, I wondered about where your ideas came from. A hallmark of your career, indeed your life, is outside-the-box thinking. How did a 16 year-old, three years later, find himself creating and teaching strategies with which today’s senior leaders still struggle?

SW: The most important influence on my thinking processes came from my parents during my growing up period. I was born and raised on a 150 acre farm—tobacco, corn, wheat—in Southside Virginia (hard by the Saylers Creek Battleground, where the Army of Northern fought its last fight.) My parents were readers, and they imbued us Wilson children with a deep love of books. My mother had been a public school teacher, and she saw to it that I—along with my older sister and three brothers—took the business of learning seriously, including what we learned in Sunday school and church, where she was my first Sunday school teacher. She taught us Wilson children discipline, self-control and how to think logically.

My father, on the other hand, fired our imaginations with his stories, songs and poetry, and helped us see things in life and in our environment in general that we otherwise would surely have missed. From an early age, we worked with him in the fields and woods, and around the farmyard, and he kept our morale up and our spirits high with his jingles and stories, many of them made up on the spot right out of the thin air. In a draft for my memoirs, titled Galahad II: A Country Boy Goes to War, I wrote:

“His mastery of ad-lib storytelling was legendary around the community. Boys from the neighborhood would frequently drop in for free haircuts—he was an expert barber. As often as not, they would be accompanied by buddies who had come along for the tale telling that came with the shearing. The whole group would sit there open-mouthed, mesmerized by the colorful nature tales of foxes, ‘possums, coon dogs, stories of hunting and fishing, of goblins and ‘hants, watermelon heists, red-tailed hawks, and river owls calling at night along the Appomattox. He gave distinct personalities to birds and animals and made them come alive. He could create more tension and drama than anyone I have ever listened to out of such subjects as a creaking door in an abandoned old farm house or strange footprints on a river sandbar in the pre-dawn mist. We would sit entranced for hours on the front porch on moonlit summer nights or by a glowing fireside during the cold of winter, listening as he spun yarn after yarn, making up his stories as he went along…”

There is no question but that my own ability, such as it is, to see things that are not there and then picture them for others to see is greatly aided by the heritage of my father.

SP: I watched the introduction you did for the film Merrill’s Marauders. At one point, in the trailer, you say:

“This was a job they said we couldn’t do. They called it impossible.”

Later, there’s a scene in the trailer, where “Stock” says:

“My man can’t make it. It’s not that they don’t want to fight, it’s that they can’t fight. They just can’t physically fight anymore.”

What inspired you and kept you motivated through your almost 40 years in the Army—much of which required accomplishing the impossible, and stretching your physical and mental limits?

SW: On motivation:

In addition to their providing a sound moral and philosophical foundation on the things that count—including love of country, I also had some appreciation from my parents—and from my own reading—for what was going on in the world of the 1930’s, and had some glimmer as to what the stakes were for the United States in the arena of U.S. foreign policy and national security. By the time I was 16, I was fired up and ready to go slay dragons. In my 1994 commencement speech at Hampden-Sydney College, I said:

“And so, let an old soldier of 3 1/2 wars, and over fifty years of public service, who has seen many men die —some, unfortunately, at his own hand, who has roamed the five continents and the seven seas, strolled in the market places from Marrakech to Baghdad to Samarkand and Ulan Bator, browsed in the book stalls of Paris, Berlin, Moscow, Peking and Tokyo, watched the sun rise out of the South China Sea and set in the Indian Ocean, the moon come up over the snows of the Himalayas and the lightning play in the peaks of the Andes, who has missed setting foot in or at least seeing only two places—Albania and the South Pole—tell you this:

“It is now your world, it is not mine anymore. And it’s a beautiful, blue jewel . . . a shining sphere. Love it, cherish it, protect it and keep it.”

And from my 1997 commencement speech at Hampden-Sydney College:

“I reach for language these old oaks have heard before and know very well. Let an old soldier who has run with the wolves and flown with the eagles tell you this: ‘Love your country. Don’t ever, ever stop loving your country. In the whole wide world we’ve got the best system there is for a man to work out his own destiny. But the system is not on automatic pilot. We have to work to make it work. Don’t forget that . . . We count on you as young men of awesome promise to do what is necessary and what is right to keep us strong and keep us free.”

On hanging in there when the going gets tough:

I felt that I could never falter or let up in front of the troops. I would sooner perish.

All my life (until now) I have always been the youngest and the least formally educated in whatever outfit I belonged to. Result: I was almost always running scared (even when I may have lapped the field—without really knowing it.) For me failure was never an option. In the draft of my memoirs, I also wrote:

“What calls forward this little vignette I have no idea. I haven’t thought of it in years. For some reason I was musing at breakfast this morning, almost in my subconscious mind, about the midnight ride to Merrill. That led to memories of Pride-and-Joy, which led in turn to recollections of Big Red.

“I recall that Big Red was almost as fast as Pride-and-Joy. When we raced the horses in the corral back in India, in the fall of 1943, to pick out the fastest one, Big Red came in second. (Lt Col Still never knew his horse placed third; Sergeant Knapp never told him, thank goodness, or Still would have taken Pride-and-Joy away from me.)

“Pride-and-Joy had a smooth, fluid motion when he ran; the sensation was one of floating along, even in full stride. But Big Red seemed to exert himself mightily, thundering along with great wheezing gasps, almost jarring the ground with the impact of his hooves. The ride was so rough that at times it was hard to stay in the saddle, especially since Big Red would go kind of crazy when you let him run full out. It would become almost impossible to rein him in.

“We were about midway of the march from Assam into North Burma over the Ledo Road. It was a mid-morning in January 1944, pushing on towards noon. The column had fallen out for a rest break, and as usual I was taking advantage of the chance to unlimber the horses a bit. This time it was Big Red’s turn, and as he began to gallop down the road along the column of resting soldiers, I decided to let him have his head.

“And he ran away with me.

“I guess nobody but me knew that I was in trouble, barely hanging on and about to be tossed at any second. We came careening around a bend in the road, and right in front of me was the command group with General Merrill, standing there with his clipboard. I can still see the pleased grin on his face as he took off his helmet and waved it as I came thundering by. Little did he know that I was running scared, not knowing how the thing was going to turn out.

“Running scared. That’s an ironic and typical commentary on the life of one SVW, hanging grimly on with a silly grin disguising his terror and wondering how he got himself into such mess.

“Running scared…Big Red becomes a metaphor for my entire life.”

In almost all my varied assignments (the majority of which I volunteered for), I was blessed with a mission, a goal that I could believe in deeply. And more often than not I had this funny feeling that I had something to offer. That made it easier, sometimes even fun, to hang on and work very hard for a successful outcome.

SP: I read the following quote from you and was reminded of the many of us who think they need to be James Bond to accomplish something special:

“Ninety percent of intelligence comes from open sources. The other ten percent, the clandestine work, is just the more dramatic. The real intelligence hero is Sherlock Holmes not James Bond.”

And in an interview with Dr. J.W. Partin, when speaking about your time training with Major General Wingate in India, you said:

” . . . we began to pick up some things from the British and their way of doing things. They were much leaner, more conservative in what they carried and in what kinds of external support they expected. In fact, we were sort of, by nature, a little spoiled. They tried to do more with less, so that was a good lesson for us.”

As you rose within the military and then became a leader helping those coming up in the ranks, how did you drive home the notion that more can be done with less—Sherlock Holmes v. James Bond—whether related to clandestine work or freshman studies in college? What did you do yourself, and what did you encourage other to do, to live the importance of being able to do more with less?

SW: Growing up on a Southside Virginia farm where we lived on things that came out of the soil, directly or indirectly, I learned early on that one not only can survive but actually thrive on very little. This lesson was confirmed emphatically in the North Burma campaign of 1944, when I came to realize that I could get by if three simple needs or conditions could be met: if I had enough to eat to keep going, if I could have a place and a chance to rest and recoup my energy, and if I could gain respite from enemy guns, especially artillery fire. I figured that if I had these three things, I could make it the rest of the way on my own. Later, I had occasion to check these observations with some of Wingate’s Chindits, and I found them in full agreement.

From another angle, as a soldier starting out in a rifle company in 1940, I was almost amazed at how little in the way of trappings and paraphernalia I really had to have in order to do my job effectively, how relatively easy it was to simplify things and get down to basics. When we would break camp in the early mornings while on maneuvers, and I would sling my pack and march away, all I owned or needed was on my back, and there was nothing left behind to show where I had slept the night before. A wonderful liberating feeling.

That conviction, arrived at early on, has been with me ever since. You can do more with less, and you really don’t need most of the things you think you do. Seeing how the British-Indian Army put this principle into practice was a revelation… And you get these points across to the troops by personal example.

The primary lesson in the Holmes-Bond analogy is not so much “doing more with less” as it is knowing in depth what your intelligence priorities are and then knowing what (and how) to look for the answers. Sometimes the critical key to unlock the whole conundrum is right there under your nose. Remember Poe’s The Purloined Letter? You have to know what to look for and how to recognize it when you see it.

SP: Two weeks ago, I did an interview with General Hal Moore. I asked him the following, and wanted to ask the same of you:

As a writer, I’ve found myself doing the same, but on an individual basis. For me, it might be that an idea comes along, and I don’t think about it or analyze it. I just act. I often attribute this to the Muse, who inspires writers. But in the military, lives are at stake. While a writer might battle over a main character’s actions, you battle in real time, pulling everything together while you are in the moment. From where do you pull this strength? And how would you advise today’s service members in particular about acting in the moment, and not overthinking and analyzing—just doing?

SW: If you have studied and trained and know your job and its requirements thoroughly, then in a fast-moving crisis when you don’t have time to think, your instincts take over and you act practically without conscious thought.

You are going along a jungle trail in North Burma when suddenly a voice in your head says, “Duck Sam, Duck Sam, Duck!” And a Jap Nambu light machine gun cuts the empty air where you had been standing. Premonition? Hardly. The almost unnoticed odor of fish heads and rice and the slight discoloration in the leaves of the branches camouflaging the enemy machine gun telegraphed danger to you without your being fully conscious of it. Trust your instincts.

SP: I asked Joe Galloway the following questions last week:

You’ve been a leader within the journalism and military community, and you’ve known legendary leaders in the military community as they’ve risen—such as General Norman Schwarzkopf, whom you met in Vietnam, and then went on to cover, and embed with during Desert Storm. Most recently, General McChrystal has been in the news, with people questioning his leadership skills. What’s your advice to our next generation of leaders, both civilian and military? What is it that has worked for you and for others?

You have a tradition of outstanding leadership yourself, and you’ve worked with, and have helped nurture future leaders. What’s your advice for military leaders in particular today?

SW: It is not easy for me to answer this question. I have been giving lectures on leadership and teaching leadership courses off and on ever since the fall of 1945, when I was involved in establishing a post-war course on the subject at Fort Benning’s infantry school. In this light, I have great difficulty responding to you in a couple of short paragraphs. Among the suggestions I might offer would be included the following:

Always strive to develop and communicate a clear-cut statement of the mission.

Stress the sharing of information, especially down the chain of command, as well as laterally.

Once you are satisfied that your subordinates know their jobs, give them their marching orders and get out of the way, while supporting them in every way you can.

Remember, take care of the troops and the troops will take care of you.

Don’t let your superiors get caught by surprise.

Study the lives of successful leaders, but at the same time don’t neglect to learn from the mistakes of those who failed.

There is so much more to be said, but this gets us started.

SP: We’ve all seen our ideas adapted by others for their own use. And during that process, our definitions are dropped/altered by those handling them. You coined the term “counter-insurgency.” I read a column that Joe Galloway wrote about you in 2004, in which he recalled:

“Samuel Vaughan Wilson stares intently at the television news from Iraq. American infantrymen are kicking in a Sunni Muslim family’s front door, yelling and screaming and manhandling the father. Wilson grimaces. “This isn’t counter-insurgency,” he says. “This is not the right way to do this.”

And in the summary of Rand’s 1962 Counterinsurgency Symposium, there is a point where it states:

“Col. Wilson emphasized the distinction—thus far inadequately stressed in our service schools—between two entirely different situations in which the Communists initiate guerilla war. In the first they will seize on existing resentment (people’s hatred of an oppressor, or their desire to recover lost privileges or property) and capture an independent movement already under way. The second is the culmination of years of communist planning an organization, as in the case of Central Vietnam . . .”

You wrote the Army’s first manual on how to do counterinsurgency. How have you felt about how something you worked on for so many years has evolved, and has been changed by others? Do you think counterinsurgency is being done right today? Or is what we’re seeing today something different, which should be titled with a different term?

SW: While serving as the director of instruction of the U.S. Army Special Warfare School (Fort Bragg), during 1959-61, and with the capable assistance of several bright, forward-looking officers, I worked to develop a program of instruction (not a manual) on counter-insurgency operations. As the subject was relatively new, this in a sense was a foundational effort, which attracted unusual attention at the time from policy levels in Washington. While trying to figure out what to call our undertaking, we settled on counter-insurgency (coin, for short), as noted above. Three years later, in the summer of 1964, I was assigned to South Vietnam where I had the opportunity to try putting into practice some of the principles we had identified at Fort Bragg. In a word, they worked. Others have been applying lessons learned since then to update, modify and improve basic coin doctrine. In this sense, General Petraeus and his warrior intellectuals have taken COIN to new levels, and I have no doubt that someone else will carry it further along in the future. To your question as to my feelings on how a subject into which I poured so much time and energy continues to evolve, I have no sense of proprietorship; this process simply reflects the dynamic nature of doctrinal development in the military world.

June 14, 2017

The Villain Doesn’t Think He’s the Villain

You and I as writers, when we want to create a really dastardly Bad Guy, may find ourselves conjuring a mustache-twirling, Simon Legree-esque, Filthy McNasty ogre, tying an innocent damsel to a railroad track.

“Me, the Bad Guy? You gotta be kidding!”

But remember, the villain doesn’t see himself as the villain.

From his point of view, he’s the good guy.

To him, the real villain in the story is the hero.

Consider this all-time-great Villain Speech, written by Aaron Sorkin and delivered to such memorable effect by Jack Nicholson as Marine colonel Nathan R. Jessup in A Few Good Men. When you read these lines (which are clearly intended to make the audience think, “Boy, is this dude evil!”), see them, if you can, as honorable and noble, not to mention absolutely true to hardball-world reality:

COL. JESSUP

Son, we live in a world that has walls, and those walls have to be guarded by men with guns. Who’s gonna do it? You? I have a greater responsibility than you could possibly fathom. You weep for Santiago, and you curse the Marines. You have that luxury. You have the luxury of not knowing what I know. That Santiago’s death, while tragic, probably saved lives. And my existence, while grotesque and incomprehensible to you, saves lives. You don’t want the truth because deep down in places you don’t talk about at parties, you want me on that wall, you need me on that wall. We use words like honor, code, loyalty. We use these words as the backbone of a life spent defending something. You use them as a punchline. I have neither the time nor the inclination to explain myself to a man who rises and sleeps under the blanket of the very freedom that I provide, and then questions the manner in which I provide it. I would rather you just said thank you, and went on your way, Otherwise, I suggest you pick up a weapon, and stand a post. Either way, I don’t give a damn what you think you are entitled to.

From Jessup’s point of view, Tom Cruise is the villain. Just look at him. An impeccably-groomed, headquarters-based lawyer who sleeps on clean sheets every night, who is not only living in a dream world with his high-minded ideas about how wars are fought and freedom is defended but who actually dares to accuse me, who stands in harm’s way, of a crime—and then paints me as the bad guy!

Or how about this villain:

GORDON GEKKO

I am not a destroyer of companies. I am a liberator of them! The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind. And greed, you mark my words, will not only save Teldar Paper, but that other malfunctioning corporation called the U.S.A.

We’re going to talk in detail about Villain Speeches in another post. Suffice it to say, for now, that a great villain has his or her own point of view, and that point of view should be just as valid, if not more valid, than the point of view of the hero.

What makes a great villain is that, though what he does is truly grisly and horrifying, possibly even planet-threatening, he’s doing it, from his point of view, for the most normal, and even honorable, reasons in the world.

The shark in Jaws is just trying to find his next meal. What’s wrong with that?

The Alien is only trying to procreate and self-actualize, to grow from a baby Alien into a grownup Alien.What’s so horrible about that?

And the Terminator? If you stopped him and accused him of wrongdoing as he’s blowing away one Sara Conner after another, he’d turn to you with an expression of shock and bewilderment.

TERMINATOR

I’m just doing my job!

June 9, 2017

Story Grid Foolscapping The Tipping Point

Here is our progress so far on our Foolscap Global Story Grid for The Tipping Point.

You remember what the Foolscap Global Story Grid is right? It’s the Big Big 30,000 foot view of an entire project from beginning to middle to end along all of the must haves it needs to satisfy its target audience.

You remember what the Foolscap Global Story Grid is right? It’s the Big Big 30,000 foot view of an entire project from beginning to middle to end along all of the must haves it needs to satisfy its target audience.

We’ve just begun to fill out the “Obligatory Scenes and Conventions” we’ll need to abide. Remember that the reason why we list the OS and Cs is to have a list to source and identify exactly where the writer made the critical choices necessary to meet readers’ expectations. As OS and Cs are the most difficult elements to innovate in a story, analyzing how the master storytellers were able to do so will be an invaluable tool for us.

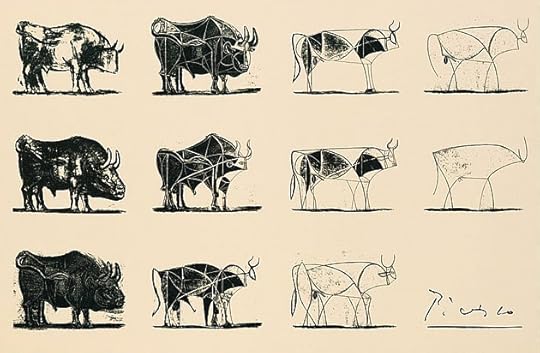

Seeing the way Picasso boiled line drawing a bull into its most essential strokes inspires artists.

Picasso’s bulls

Seeing the way Malcolm Gladwell somehow delivers a “hero at the mercy of the villain scene” in his external genre Action Adventure component in The Tipping Point will be equally thrilling.

Let’s review the OS and Cs that Gladwell faced for his Big Idea Nonfiction project.

1. Hero/Victim/Villain

The first one we’ve listed is the crucial convention of the Action Adventure story, the necessity of having a cast that includes at least one hero, at least one victim, and at least one villain. We’re clear that we have that convention covered. Here’s the post that explored that necessity.

2. Destination/Promise

What we also need in an Action Adventure Story is a clear Destination. What I mean by that is we need to be given a quest at the very start of the story that has a clear purpose. I always use L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as the epitome of the Action Adventure Story and its destination is, of course, The Emerald City, the center of Oz where the Wizard resides.

In the case of the Big Idea Nonfiction Story, the destination is not just understanding the Big Idea itself, but applying that understanding to get a clearer view of the world. The Destination/Promise is applicable knowledge.

3. Path/Methodology

The third thing we need in an Action Adventure Story is a clear path to the destination, a yellow brick road. By following the path we will reach the promised land.

In the case of Big Idea Nonfiction, the path is inherent in the methodology of the investigator/narrator. And that methodology is the logical progression of the storyteller’s adherence to the universally accepted form of discovery—the Scientific method.

4. Sidekick/s

The sidekick/s in an Action Adventure Story are the equivalent of the scarecrow, the tin man, and the lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. These characters exemplify a component of the global hypothesis. For example, in The Tipping Point Gladwell introduces the reader to everyday people like Roger Horchow, Lois Weisberg, and Mark Alpert to represent building blocks of his theory.

5. Set Pieces/Weigh Stations

The Action Adventure Set Pieces are mini-stories within the global story. Essentially these are sequences with a central dilemma that must be solved before the global story can move forward. If Dorothy does not throw water on the Wicked Witch of the West after she’s been abducted by the witch’s winged monkeys, we’d never learn the truth about the Wizard of Oz.

Similarly in a Big Idea work of Nonfiction, if we are not convinced by Malcolm Gladwell’s assertion that products/ideas tip in much the same way as viruses overwhelm a host, we’d never understand the importance of “stickiness.”

It’s important to remember that the storyteller needs to escalate the stakes of each of the Set Pieces/Weigh Stations as the global journey/story progresses. Just as L. Frank Baum had to figure out exactly where in the hierarchy of danger the winged monkeys fell, so does Gladwell have to prioritize the set pieces/weigh stations of his global story. Gladwell doesn’t begin The Tipping Point with the set piece/weigh station about suicides in Micronesia. He builds to them with lighter fare about Hush Puppies and less specific examples about overall crime rates in New York. It’s not the evidence presented in a Big Idea Book that makes it compelling, it’s the order in which the writer chooses to deliver the evidence…

6. Hero at the Mercy of the Villain Scene

The “hero at the mercy of the villain” scene is the core event of every action story including Action Adventure. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz moment is when the Wicked Witch of the West has Dorothy on the ropes. She’s gonna get our heroine’s shoes and then all will be lost. That’s when Dorothy melts the witch with the water.

Malcolm Gladwell clearly states that he’s written an Intellectual Adventure Story so we need to figure out exactly where and when he gives us the “hero at the mercy of the villain” scene. I have some ideas about that but I need to take my time and really parse it out in the Story Grid Spreadsheet of The Tipping Point before I’ll share them.

Those are my big six OS and Cs for Action Adventure. So I’m going to note them on my Foolscap for The Tipping Point.

I’m also going to add three more must-haves to cover the necessities for the Internal Genre, Worldview Revelation, in the Big Idea Nonfiction book. They are:

7. A Blatant Statement of the Controlling Idea

Unlike fiction’s controlling idea/theme which is delivered in subtext, for Big Idea Nonfiction, the controlling idea must clearly be stated. In as few words as possible. As soon as possible. The statement of the big idea is the inciting incident of the entire Big Idea Book. It’s the must-have throwdown raison d’etre of the book–after years of diligent hard work, here is what I’ve discovered. Now follow me and I’ll walk you through exactly how I pieced this life changing information together and then I’ll tell you how to apply this information in your own life.

8. Ethos/Logos/Pathos

As I wrote about here, the Big Idea Nonfiction book must use all three forms of argument to build/prove its case.

9. Ironic Payoff

Lastly, the Big Idea Nonfiction book must “turn.” What I mean by that is that while the promise of the book (proving the idea and then giving the readers the necessary tools to apply the idea) must be paid off, it also must do so with a surprising twist.

The pursuit of the idea and applying it potently reveals a deeper truth, one that the storyteller delivers to the reader at the ending payoff.

In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the irony is that the Wizard is impotent. It is the power within each of the characters who seek his approval/permission that truly grants them their wishes. Not the Wizard’s magic.

So it is in The Tipping Point… To tip a product or a behavior is not all it’s cracked up to be. In the end, the book reveals that scale requires compromising sacrifice and that it also has a very dark side. So while empowering, to know how to tip something is also potentially catastrophic. There is as much darkness inherent in The Tipping Point as there is light. It is a viral phenomenon in every sense of that word.

June 7, 2017

Give a Star a Star Speech

Actors will admit it, if you ask: the first time they read a script, some part of them is scanning it for a great speech they can deliver.

“Do ya feel lucky, punk?”

A star speech.

A speech that says, “This is my movie (or my book).”

It’s our job as writers, yours and mine, to give that star a star speech.

A star speech can be long.

I believe in the small of a woman’s back, the hanging curveball, high fiber, good Scotch … I believe that the novels of Susan Sontag are self-indulgent overrated crap. I believe Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone. I believe there should be a constitutional amendment outlawing Astroturf and the designated hitter. I believe in the sweet spot, soft-core pornography, opening your presents Christmas morning rather than Christmas eve and I believe in long, slow, deep, soft, wet kisses that last three days.”

It can be a soliloquy.

To be or not to be, etc. etc.

A star speech can also be short.

“Go ahead, make my day.”

“Toto, I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore.”

“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

A star speech doesn’t even have to be spoken by the star.

“You run away once, you got yourself one set of chains. You run away twice, you got yourself two sets. You ain’t gonna need no third set, ’cause you gonna get your mind right.”

“I’ll have what she’s having.”

Estelle Reiner referring to Meg Ryan in “When Harry Met Sally”

But a star speech has to be memorable. It has to articulate the star’s point of view/philosophy/dilemma. It has to be a line or lines that only the central character of the book or movie (or a supporting character referring to that central character) can legitimately deliver.

“What a dump.”

“Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

“I ate his liver with some fava beans and a nice chianti.”

I know, I know. It ain’t easy to deliver lines like these on demand. I’ll bet the writers on Sudden Impact filled page after yellow page with candidates, answering Clint Eastwood’s directive, “Gimme a line people are gonna remember.” (Or, who knows, maybe Make my day appeared in the script organically.)

In any event, we want that line.

Our star wants it.

The audience/readers want it.

“She’s my sister. She’s my daughter … ”

June 2, 2017

The Value of Words

Numbers are concrete.

Unless they’re being manipulated by a slug, I don’t look at “2” and wonder if it is really “4.”

I know that the absolute value of 2—whether it has a negative sign in front of it or not—is still 2, because numbers are ultimately about distance. Both 2 and -2 take up two spaces on the number line, whether I’m moving forward or backward.

Imagine words being absolute numbers.

The “2” version of your words convey the exact same meaning, whether presented in the positive or negative. One absolute value, void of interpretations.

Below is an example from a recent e-mail, where the words and message exist on different planes.

What was written:

My client likes you book. He’s a big deal in the film industry and I want to give him a signed copy. Can you sign and overnight it to this address xxx xxx xxx?

What was likely meant:

I’m trying to kiss my client’s ass and I need your help.

How it could be translated:

I’m trying to kiss my client’s ass and I want you to bend over backwards to help, even though I’ve never met you, have had no contact with you, and will not offer to pay to send you the book or pay for shipping because you are an author and must have copies that your publisher sends you for free just sitting around your house, and because you’re a recognized author, you must have a ton of extra money and time to deal with my self-serving request.

With words, there’s a lot of wiggle room. They are not absolute. Baggage makes them so.

Every time a new message arrives, the lens through which we view it switches out, like an optometrist’s test kit.

If we’re on the writing end, we have to know that the intended interpretation could be missed.

What to do?

Let’s rework the e-mail above.

What should have been written:

I have a client who admires your work.

I’ve enjoyed working with him and want to do something special to thank him.

I know this is a lot to ask, but would you consider signing a book to him?

If yes, I’d make it as easy as possible for you. I’ll buy a copy of the book and send it to you with a FedEx return label, so all you have to do is call for a pick-up.

Thanks for considering the above,

Best,

What you would have meant:

I have a client I like—and I want to send him a thank you present that I know would make him happy. I know you don’t know me, but I’ll make it as easy as possible if you are able to help.

How it would have been translated:

I’m a nice guy. I have a nice client. I want to do something nice for that nice client. I need your help. If you help, I promise I’ll make it as easy as possible for you.

Get your words as close to their meaning.

Say what you mean and drop everything in between.

PAY SPECIAL ATTENTION:

In the last few months, Steve has received a few e-mails from individuals asking him to review their books, which include links to where Steve can pre-order the books on Amazon.

No offer to send a free book.

No offer to pay for shipping.

Just a request that he spend his time and money on a complete stranger.

If you use extra words to say what you mean, make sure they are dripping in Kindness and Consideration.

May 31, 2017

Writing a Great Villain

The easiest villain to write is the external villain. The Alien. The shark in Jaws. The Terminator. Doc Ock, Bane, Immortan Joe. Or force-of-nature villains—the volcano in Volcano, the oncoming Ice Age in The Day After Tomorrow, the Mayan-prophecy-end-of-the-world in 2012.

The villain in “ALIEN: Covenant.” Can we do better?

External villains present existential threats to our physical existence. These sonsofbitches will kill you, eat you, freeze you, boil you.

The problem with external villains, though they may occasionally deliver bestseller sales and boffo box office, is they don’t often bring out the best in the stars who must confront them.

Why? Because the stars only have to duel these villains on one level (and the most superficial level, at that): the physical.

Much higher on the Villain Food Chain are

Societal villains.

Interior villains.

The villain in Huckleberry Finn, To Kill A Mockingbird, In the Heat of the Night and many, many others down to The Hurricane, Precious, and The Help, is racism.

Racism is a societal villain.

An individual character or characters may personify this antagonist in our narrative, as the jury or the mob or Bob Ewell did in Mockingbird. But the real villain is all-pervasive. It’s that cruel, ignorant, evil belief—”I have a right to dominate you because my skin is a different color than yours”—that exists only in men’s minds and hearts.

Societal villains are great villains, and they have produced great stars/heroes to confront them.

Do you remember The Way We Were? The Way We Were was a vehicle for two superstars in their prime, Robert Redford and Barbra Streisand, and it provided both of them with roles worthy of their peak power.

Who was the villain?

The villain, again, was societal. It was the ethno-racist belief that “Park Avenue” was different from “Brooklyn” and that people whose characters were formed in such environments—WASPy, athletic, born-golden Hubbell Gardiner and Jewish, striving, up-from-the-streets Katie Morosky—could never truly come together.

Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford in “The Way We Were”

The chasm between them because of their ethnicities and the different worlds they grew up in was so vast that it could not be bridged even by a great love.

The villain wins in the end of The Way We Were.

But the battle against this antagonist—the passionate, complex, tragic struggle by Katie and Hubbell to maintain their love—is an epic, world-class throwdown, with layer upon layer of emotional and psychological depth. The clash with this villain was worthy of two superstars.

The stars made the roles, but the villain made the stars.

The third type of villain, and the most satisfying dramatically, is the interior villain.

The interior villain is inside the star herself.

Karen Blixen’s need to “possess” the things she loves.

Hamlet’s inability to make up his mind and act.

Gatsby’s dream of recapturing a past that never really existed.

External villains exist as metaphors. The Alien represents … what? Pure evil? Death? Pitiless fate?

But interior villains show us the demons you and I really deal with in our real lives—the crazy shit inside our skulls.

Silver Linings Playbook made stars out of Bradley Cooper and Jennifer Lawrence.

One reason: a great villain.

“So think about that dance thing.” Bradley Cooper and Jennifer Lawrence in “Silver Linings Playbook.”

The villain in Silver Linings Playbook is interior. It exists inside Bradley Cooper’s head. The villain is his obsession, fueled by his bipolar disorder, with winning back his wife Nikki, whom he has alienated by his extravagant behavior in the past.

This villain is in every scene of the movie, from first to last.

PAT (BRADLEY COOPER)

[Nikki and I] have a very unconventional chemistry. It

makes people feel awkward, but not me. Alright? She’s the

most beautiful woman I’ve ever been with. It’s electric between

us! Okay, yeah, we wanna change each other, but that’s normal,

couples wanna do that. I want her to stop dressing like she

dresses, I want her to stop acting so superior to me, okay?

And she wanted me to lose weight and stop my mood swings,

which both I’ve done. I mean, people fight. Couples fight. We

would fight, we wouldn’t talk for a couple of weeks. That’s

normal. She always wanted the best for me.

TIFFANY (JENNIFER LAWRENCE)

Wow.

PAT

She wanted me to be passionate and compassionate.

And that’s a good thing. You know? I just, look, I’m my

best self today and I think she’s her best self today, and

our love’s gonna be fucking amazing.

TIFFANY

It’s gonna be amazing, and you’re gonna be amazing,

and she’s gonna be amazing, and you’re not gonna be that

guy that’s gonna take advantage of a situation without

offering to do something back. So think about that

dance thing.

See the villain in there? It’s in every word and it’s more terrifying than the Alien and the Predator and the Monsters of the Id from Forbidden Planet. This demon will devour not just Bradley’s soul but Jennifer’s too if it can, and it’s in every cell in Bradley’s body, as invisible to him as water is to a fish swimming in it.

What a hero Bradley will be if he can somehow, either alone or aided by Jennifer, see the real love that’s staring him in the face and recognize this Nikki-self-delusion for the monster it is—and change himself.

Spoiler alert: he does.

That’s a hero.

That’s a star.

(And count Jennifer too, because she’s fighting the same villain.)

What made that star was the scale and depth of the villain he (and she) had to fight.

May 26, 2017

First Story Gridding Steps

We’re story gridding The Tipping Point.

Why are we doing this again?

The reason why we want to story grid the book is to discover how Malcolm Gladwell crafted an indelible story…one that not only sold millions of copies, but also changed the way we view our world.

Story Grids are the blueprints/CT scans that teach us how to solve problems we face in our own writing work. Pinpointing exactly where and how the masters created masterworks not only inspires our future projects, but more importantly, it teaches us that blue collar labor is the path that the professional takes on his or her creative journey.

Nonfiction story gridding allows us to witness these writers with their sleeves rolled up, with grease on their hands. We can literally see how they practically managed the narrative momentum in a book that could have easily been as dry as dust. That management requires a deep understanding of story structure. And the test that there really is a story underneath the scholarship is the story grid.

Yes, of course some of the great writers were probably born with some innate DNA-laden storytelling talent. But without the blue-collar work ethic to give that talent the freedom to express itself, we’d never be the beneficiaries of their art.

I’d wager the pantheon of literary greats is far more representative of “grinders” than “naturals.”

No one sits down and writes a perfect first draft. Trust me on this. It’s never happened. What real writers understand is that the first draft is the raw material—the slab of marble, the bag of moist clay, the bricks, the blank canvass and paint, the zeroes and ones…

It’s important to remind yourself of this fact every single day. It’s the little things, those incremental drip, drip, drips of inner bullheaded, stubborn discipline that matter in the end.

Fight that inner war doing the work you were put here to do every day and the rest will take care of itself. Seriously.

Back to the task at hand…story gridding The Tipping Point.

My end of the line destination is to create a Story Grid infographic for The Tipping Point just as I did for Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs, a visual representation of the building blocks of the Malcolm Gladwell’s Story.

The second thing I remind myself is that in order to create that infographic I need to have two documents in front of me.

The Foolscap Global Story Grid for The Tipping Point

The Story Grid Spreadsheet for The Tipping Point

The Foolscap Global Story Grid is the MACRO/30,000 foot view of the book and The Story Grid Spreadsheet is the MICRO/scene-by-scene view of the book.

While I’ve not yet written about the MICRO Story Grid Spreadsheet for The Tipping Point in these posts, I’ve already broken down the bits of the book into 51 scenes that amount to 74,139 words (an average of 1453.7 words per scene, see here for more on the Math of a Story). And I’ve begun work filling in all of the columns for each of those scenes.

Lots left to do on that MICRO front.

But the great thing about doing the work for The Story Grid Spreadsheet is that it’s fact based rather than intensely analytical. It’s a matter of reading each scene. Then answering the question posed by a column in the Spreadsheet. Filling in the blank of that column for that scene. And then re-reading the scene again to answer the next question from the next column and so on. Drip, drip, drip.

It’s like pointing bricks. Move from one brick to the next brick to the next. You finish a row, you move to the beginning of the next row and so on…

The MACRO Foolscap Global Story Grid only requires the editor to answer six questions:

What’s the Genre?

What are the conventions and obligatory scenes for the Genre?

What’s the Point of View?

What are the objects of desire?

What’s the controlling idea/theme?

What is the Beginning Hook, Middle Build, and Ending Payoff?

I’ve been poking around all of these questions in search of answering the very first one, What’s the Genre?

As you know, figuring out the Genre/s is a paramount series of choices for the writer. Because Genre choices satisfy reader expectations. If you don’t set up and satisfy a reader’s expectations, your Story won’t work.

What do we know so far about The Tipping Point Genres?

We know that the Global Genre of The Tipping Point is Big Idea Nonfiction.

We know that the External Genre of The Tipping Point is Action Adventure.

From The Story Grid book we know that the External Value at Stake in an Action Adventure Story is Life/Death.

And we know that that the spectrum of value for Life/Death moves from: Life to Unconsciousness to Death to Damnation.

For more about Story values and the spectrum of value, read this.

What about the Internal Genre of The Tipping Point? What’s that?

Remember that my interpretation of the Internal Genres derives from the work of Norman Friedman and his seminal paper “Forms of the Plot” in the Journal of General Education.

They are:

Worldview: connotes a change of seeing the world one way and by Story’s end, seeing it differently.

Morality: connotes a change in the moral or ethical character of the protagonist.

Status: connotes a change in social position of the protagonist

As The Tipping Point is a Big Idea work of Nonfiction, it’s obvious that its Internal Genre is Worldview.

Can we categorize it further?

Yes.

Worldview, has four subgenres. They are:

Education: a shift in view from life as meaningless to meaningful

Maturation: a shift in view from naivete to worldliness

Revelation: a shift in view from ignorance to wisdom

Disillusionment: a shift in view from belief to disillusionment

Of those four subgenres, it’s again obvious that we’re in the Revelation arena. A Big Idea book is one that shifts our understanding of the world from ignorance “not having enough information, but capable of comprehension” to wisdom/knowing.

Great. We now know that the Internal Genre of The Tipping Point is Worldview Revelation. We can also file away in our minds the fact that all Big Idea Nonfiction has Worldview Revelation as its Internal Genre.

That makes a lot of sense right? A Big Idea Book is all about revealing the truth about a particular idea in such a way that the reader, by book’s end, is convinced of the controlling idea. The Big Idea Book is by definition a revelation.

What about the value at stake in the Worldview Revelation genre? What’s that?

The value is Wisdom/Stupidity.

And the value spectrum of Wisdom/Stupidity from it’s most negative to it most positive moves as follows.

Stupidity perceived as Intelligence to Stupidity to Ignorance to Wisdom

I was reluctant to use the word stupidity as the opposite of wisdom because it has such a fuzzy feeling in the mind. We’ve heard “stupid” so many times that we lose the core meaning of the word. So it’s worth reiterating it’s core meaning:

Stupidity means that no matter the information available, one is incapable of or unwilling to understand. Stupidity is resolute.

Ignorance on the other hand is a temporary unknowing due to lack of information. Once the information is available, though, the ignorant become enlightened and gain wisdom.

The negation of the negation of the Wisdom value is the fate worse than just stupidity, Stupidity perceived as intelligence. An example of in its most obvious form would be back in the days when man believed earth was flat.

Looking back it seems silly that anyone would believe that the world was flat, but when society pushes a known “fact” on the individual from birth, few have the temerity/courage to challenge the status quo.

What it takes to achieve human progress are explorers and innovators with the nerve to weather the slings and arrows of their contemporaries while they cast their light into the darkness. Torchbearers willing to lead…to sacrifice their own lives/reputations if necessary in order to inform the rest of us as we take our mild baby steps behind them in our own private journeys from ignorance to wisdom.

As Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld once said:

“There are known knowns…there are things we know we know. We also know that there are known unknowns…that is to say we know that there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns…the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

The Big Idea Book is all about those unknown unknowns and The Tipping Point is an epitome of the Genre.

May 24, 2017

Clueless Asks

I turn down all clueless asks.

Alicia Silverstone in “Clueless:”

What exactly is a clueless ask?

Anyone who sends me their manuscript unsolicited.

Anyone who asks me to meet them for lunch.

Anyone who sends me an e-mail headed “Hi” or “Hello there” (or with no salutation at all.)

Anyone who asks me how to get an agent.

Anyone who asks me to introduce them to my agent.

These are not malicious asks.

The writers who send them are nice people, motivated by good intentions.

They’re just clueless.

They have committed one of two misdemeanors (or both).

First, they have demonstrated that they have no respect for my time—and no concept of the value of what they’re asking me for.

Do I have two hours to meet somebody for lunch? In the middle of the working day? Why? To shoot the shit about scene construction and character development?

Or maybe the asker “admires my work” and would like to “pick my brain.”

Really?

Send me a check for $10,000 and when it clears I still won’t meet you for lunch.

Or maybe the asker wants me to blurb their new book.

Why would I do that?

Do I know them? Did we go to school together? Did we serve in the same battalion? Am I married to their sister?

The real ask in these cases is “Can I have your reputation?” In other words, “Will you give me, for free, the single most valuable commodity you own, that you’ve worked your entire life to acquire?”

The second crime these clueless askers commit is they have not done their due diligence.

Don’t ask a writer how to get an agent. Find out yourself. There are ten thousand sources online and a hundred books in the Writing section of a book store.

Don’t send a writer an e-mail with an attachment that contains your novel. What if I’m writing my own novel on that same subject? When mine comes out, you’ll sue me for plagiarism and tell the judge, “See, I sent him my book. He ripped me off!”

My lawyer won’t let me read anything that comes in unsolicited, for just this reason.

Do your research.

Learn good manners.

Find out how the business works.

My book Gates of Fire gets assigned sometimes to high school English classes. I get asks from kids to explain the theme, the structure, and the relationship of Character X to Character Y. You can see that the student (one wrote, “Please respond. Money is no object.”) has simply typed the teacher’s assignment verbatim into the e-mail.

These, I suppose, are not technically clueless asks.

They’re more like, “Hey, Stupid, lemme see if I can take advantage of you” asks.