Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 55

November 10, 2017

The Context of No Context

Before Malcolm Gladwell’s re-invigoration of the “Big Idea” work of nonfiction sprang from the pages of The New Yorker, the in house writer who owned the crown of putting forth a big think piece with aplomb was George W. S. Trow. Here’s a post from www.storygrid.com about Trow’s prophetic distillation of what ails us today.

We’ve all had experiences like this.

Some kid moves into our neighborhood and shows up for baseball tryouts. He steps up to bat and blasts screaming line drive after screaming line drive into the left center and right center field gaps. And then he takes the field and plays shortstop like Ozzie Smith. And he does it all seemingly effortlessly.

Or a new saleswoman shows up at our retail job and gets the nastiest/most impossible customers to actually take out their wallets and pay for something. The cranky consumers even leave the store happy. Not just with their purchase but unbelievably happy with their lot in life.

I don’t know about you, but I can barely suppress my internal rage when these kinds of magical people enter my life. They seem to do no wrong and irritatingly push me down a notch, or ten, on mine own private hierarchical totem pole. Leapfrogging over me, they seem to have been touched by greatness while poor I feel like I’ve been rubbed by a bad case of mediocrity.

Now imagine being writer George W.S. Trow in 1996, witnessing the arrival of writer Malcolm Gladwell at The New Yorker.

After he was tapped by birth to complete the east coast blue blood prep circuit, Trow matriculated with the necessary distinction at Philips Exeter Academy. Then on to Harvard, like about half his classmates, he did go. He served as President of The Harvard Lampoon and a few years after graduation, he sowed his oats as a sometime contributor at the Lampoon’s offshoot founded by fellow Cantabridgians Doug Kenney, Henry Beard and Rob Hoffman, The National Lampoon.

But his real work was writing for editors William Shawn and Robert Gottlieb at The New Yorker. The legendary Mr. Shawn who ran the magazine from 1952 through 1987 brought Trow onto the invisible masthead right out of Cambridge in 1966. Primarily to write pithy “Talk of the Town” pieces.

But it was Trow’s deep-think BIG IDEA piece that made his name.

After editing it personally, Mr. Shawn was so enamored with the work that he devoted just about the entire November 17, 1980 issue to it. Published under The New Yorker rubric “Reflections (The Decline of Adulthood),” Within the Context of No Context was a punch to America’s psychic solar plexus. If you hold a certain Weltanschauung similar to my own, reading it today is both enormously comforting in its diagnosis of what generally ails us; and equally depressing in its refusal to put forth any possible remedy.

A brilliant look at the raison d’etre of television—creating false “contexts” to prime the engine of mass consumption…i.e. be like these fake people and buy what they buy and all will be well—Within the Context of No Context lays bare the corrosive effects of mindless plugging in to the boob tube. With nothing beyond entertainment designed to spread sales pitch consumption memes, television/media creates and reinforces Groupthink at a monstrous scale. Trow’s article (which was reissued as a book) nailed the thing behind what President Jimmy Carter infamously described in his “malaise” speech of July 15, 1979 as America’s “crisis of confidence.”

But when the masses equate consumption with happiness—when the marketplace reigns—what happens when the grand economic engine sputters? Carter sealed his fate as a one-termer POTUS with his trenchant answer.

But Within the Context of No Context is also unmistakably a lamentation of noblesse oblige nostalgia…for the time when the world had an unmistakable eastern establishment structure. Trow recalls those wondrous days when men wore Fedoras. Without irony. A boy of particular breeding could depend upon the way things worked in the adult world. He knew where he’d fit and where he wouldn’t. Follow the Fedora and all would be well.

Unlike Malcolm Gladwell, who had to build a body of work (what some would call creating and marketing a personal brand) before gaining entree, Trow was hired a staff writer at The New Yorker straight off of Harvard Yard. It’s not surprising that shortly after Tina Brown displaced Robert Gottlieb as The New Yorker’s editor, Trow resigned. (For a dazzling extended piece about Trow, I recommend Ariel Levy’s)

The Exeter/Harvard/New Yorker trifecta made sense in Trow’s day. A to-the-manor-born writer was tapped and then served his ten thousand hours learning his craft under tutelage at a prestigious institution/company. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Trow wrote his seminal work fourteen years after he started at the magazine. Trow needed that time to find his voice and Mr. Shawn bestowed it upon him…as was his custom.

For good or for ill, you won’t get patrician grooming at a magazine or publishing house today.

While extremely stressful for the individual and lacking in any grand noble vision beyond getting “ahead” through the accumulation of capital or status, the free market mentality that Trow characterized in his Within the Context of No Context is the origin story of contemporary American culture.

While often dispiriting and demoralizing, what the market does allow is for that kid from across town that has been hitting baseballs off a tee religiously all winter to show up at baseball tryouts and win a job. Sometimes he even takes the coach’s kid’s position.

And despite appearances of wunderkind arrival at The New Yorker, Malcolm Gladwell didn’t come out of nowhere. He was not touched with greatness nor was he tapped as one worthy of institutional training by virtue of his birthright.

He came to his place at The New Yorker not the old-fashioned way, but in the way all of us must find our place today. He earned it.

I imagine that George W.S. Trow may have despaired after he’d read Gladwell’s third piece for The New Yorker on June 3, 1996. Probably not because he thought Gladwell was some miraculous hack who’d come on the scene to take his place as preeminent cultural observer. A pro recognizes another pro and Gladwell’s piece is so professionally constructed that Trow would have admitted as such. Trow was obviously a complicated snob, but even a snob recognizes quality.

Trow would have despaired because what Gladwell was getting at in The Tipping Point confirmed his deepest fear. That the marketplace had become so deeply ingrained in our collective worldview that we accept, without protest or even consciousness, that we’re just behavioral protoplasm capable of being arbitrarily manipulated. Resigned suckers content to follow the crowd.

That is, we no longer see ourselves as self-directed thinking machines capable of personal choice. Instead, we’ve come to accept our place as just a cell within a mass…a mass capable of being poked or prodded into a collective response by invisible Svengalis. We buy Hush Puppies and repress urges to commit crime by rote. And we don’t find that notion all that troubling, either. In fact we wish to harness this obvious truth to our best advantage. We wish to become one of those Svengalis ourselves.

In the end, I think what Trow would have taken away from Gladwell’s piece was that in our the market is the message era, the only value of Context is as a reactant within a chemical formula—like one part hydrogen plus two parts oxygen reacts to produce water.

And that kind of thinking–that there is no meaning within a Context beyond its relationship to producing a response–is a bummer. As Gertrude Stein said, “there is no there there.”

Others, though, had a wildly different response to The Tipping Point piece in The New Yorker. They saw the makings of a huge bestseller. If Gladwell were able to flesh out his thesis and deliver the formula for making things “tip,” it would be a license to print money.

More on that to come.

November 8, 2017

Everybody Loves the Bad Guy

Shakespeare, Milton and Dante all understood villains. They loved villains. Their villains are their greatest creations.

The Bible is loaded with spectacular villains, as are all cultural myths from the Mahabharata to the Epic of Gilgamesh to the saga of Siegfried.

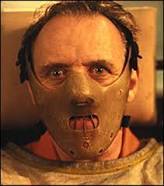

Is he the greatest villain ever?

Great villains eclipse even the heroes who vanquish them.

Flash Gordon was a pale shadow alongside Ming the Merciless.

Clarice Starling was cool, but who could forget Hannibal Lecter?

The villain not only steals Paradise Lost but walks off with the most unforgettable line.

SATAN

Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.

Film directors relish villains because villains light up the screen. Actors love to play Bad Guys. What onscreen outrage could be more memorable than crushing a half-grapefruit into your wife’s face, as James Cagney did to Mae Clark in Public Enemy, or, as Richard Widmark’s unforgettable act of villainy in Kiss of Death, pushing an old lady in a wheelchair down a flight of stairs?

Wait, what about this guy?

James Bond always goes up against diabolical villains, as do Superman, Batman, Spiderman and Iron Man. How many franchises (Alien, Terminator, Jaws, Predator) are driven not by heroes but by villains?

The more years I labor in the storytelling racket, the more I appreciate the value of a great antagonist.

For you and me as writers, our bad guys may be more important even than our heroes.

[For the next few weeks we’re going to return to our series on Bad Guys, which we started a while ago and then moved off from for our “Reports from the Trenches.” More on villains next week.]

November 3, 2017

I Solemnly Swear to Tell the Whole Truth

In 2006, I was named Time Magazine’s person of the year.

Imagine my surprise—especially since I didn’t find out until three years later, in 2009.

Around the 2009 period, a blogger entered my world like a fly at a picnic. I noticed him circling a few times, then he seemed to be everywhere—and not in a good way—so I checked out his bio. It said he was Time Magazine’s person of the year for 2006.

Dumbstruck, I did some Googling and found that I, too, was person of the year.

Gobsmacked?

You bet.

I was person of the year—and so were you. In fact, we were all person of the year because, in 2006, Time named “You” its person of the year.

I thought it was clever. The blogger told the truth and beefed up his bio in the process.

He created what a lawyer friend of mine referred to as an intentional hole. A lie isn’t stated, but smack dab in the middle of the statement is a hole in the truth, rather than the whole truth. Here’s an example:

When my kids were small, my husband and I decided to bail on Winter’s remaining days and hit a heated indoor waterpark for a weekend with the kids. A few days before we were set to go, Spring made a surprise visit. It was gonna be in the 70s, without a cloud in the sky—and the last thing I wanted was to hang out inside. I called the hotel, explained we might not come, and asked if there was an outdoor pool. The receptionist answered with an affirmative yes, so off we went.

When we arrived, we found the pool doing an impression of a 70’s era California skater’s paradise. No water. Completely drained. But yes, there was an outdoor pool. She hadn’t lied—and I hadn’t thought to ask the follow-up question, “Is there water in the outdoor pool?”

She gave me the hole truth, not the whole truth.

I ran across the hole truth on a pitch the other day, asking Steve to be on a new podcast. At the bottom, the host stated, “Invited guests have included . . . “ and then listed some well known names.

“Invited guests” is different from “guests.”

Just as I thought the blogger clever a few years earlier, I thought the podcast host clever, too. Clever, but bothersome.

It’s tempting to tell the hole truth. Doing so might help you gain attention or make your case, but… It will catch up with you.

Clever doesn’t garner respect. It wins lawsuits, perpetuates lies, and deceives.

Just look at what happened after this cleverly written line was stated, “Cigarette smoking is no more ‘addictive’ than coffee, tea or Twinkies.”

November 1, 2017

Nothing New After Act Two

One of story checkmarks you learn writing for the movies is

Every main character should be introduced in Act One.

Though Harrison Ford wasn’t onscreen early in “Blade Runner 2049,” he was in our minds from the original “Blade Runner”

This precept is probably not as critical for novels, where we have more time for the story to unfold and for new faces to appear. But it still seems to me a good rule.

Get everybody onstage early.

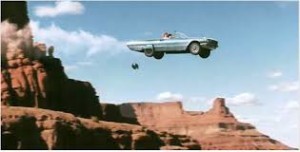

(Including key props and concepts like the ’66 Ford Thunderbird convertible that Thelma and Louise will have their adventures in and the Tyrell Corporation’s invention of the latest series of replicants.)

The last thing we want is for some important character to wander onto the scene on page 286. It feels like a cheat. The reader, remember, is solving the story puzzle along with us as she reads. She’s asking herself, “Will Elizabeth Bennet wind up with Mr. Darcy?” If we, the writers, hold back some important character—say, a possible rival for Liz’s hand—the reader will feel we’re not playing fair with her.

Likewise, and for the same reason, we risk alienating the reader if we bring in ANYTHING new in Act Three.

Act Three, as we said last week, is the ninth inning. In the third act, we put the pedal to the metal and highball into the climax.

In the story I’ve been working on (the “Reports from the Trenches” story), I kept a file I called Stuff We Need to Get In. In it were four or five of what I thought were really cool concepts or insights that the reader would like and that would really enhance the story.

Then I got to Act Three.

Get that T-bird onstage early.

Each time I thought to myself, “Ah, here’s a spot we can get in Thought #1,” I realized it was too late. The story was rolling too fast toward the climax. If I paused, even for a single extra paragraph, the momentum would stall. So …

Cut.

Cut.

Cut.

One by one, my cool little notions bit the dust.

The good news: when I looked back, I realized I didn’t miss them.

Momentum is everything in Act Three.

Once Luke and his buddies are closing in on the Death Star, there’s no time for backstory about Chewbacca.

Once Ahab learns that Moby Dick is just beyond the horizon, it’s, “Set all sails, ye lubbers!”

Nothing new after Act Two.

October 27, 2017

A Sub-Genre of One’s Own

When I find a story fascinating, like I obviously find THE TIPPING POINT, I can’t help but think about the writer. What drove him or her to tell it? I have a grand theory that there is something deep within them that drives them…something that they need to work out in their own minds that directs them to explore a particular genre and carve out a space inside of it of their own. I also believe that they are not consciously aware of their internal north star…

In this next post edited from the www.storygrid.com archives, I explore what may have driven Malcolm Gladwell to create his own particular kind of story…what I think of as the debunking of conventional wisdom narrative…a sub-genre of the Revelation Story.

Malcolm Gladwell, back in 1998, faced the same writing dilemma writers do today. As he sat down to the pile of rough “Tipping Point” book materials on his desk that would be fodder for his first draft, he must have feared criticism, failure, indifference…all that stuff.

While the intangible things he had no control over must have terrified him (other people’s opinions of his ideas) I’m confident that the one thing he didn’t fear was the work. Perhaps the difference between Gladwell and the amateur susceptible to impotence anticipating third party criticism, is that he’d worked his ass off for twelve years hitting story deadlines time and time again as a magazine and newspaper journalist.

The man knew how to deliver. But perhaps not at this level…

It was the constraints—those rare positive seven figure expectations—Gladwell had to toil under that could have driven him crazy. He didn’t just have to deliver a manuscript that would be edited and copyedited and proofread and dumped into a publisher’s catalog on page 37 next to another writer’s mid-list business book. He had to deliver a 1.5 million dollar book…a BIG BOOK that would be a two-page spread, front of the catalog big deal, with every one of his publisher’s marketing bells and whistles attached to guarantee its bestsellerdom.

How did he find himself in this predicament?

How did he reach a place in his writing life when a powerful literary agent picked him as her next development project? From the rich stew of journalists that publish their work every month, or week or even every day in all of the “A-list” periodicals across the country and even around the world?

Gladwell doesn’t have a post-graduate journalism degree from Columbia. He isn’t an Ivy Leaguer B.A. either. And he’d only just begun writing for The New Yorker when he got his “big break.”

So what gives?

I think three things were instrumental in his inevitable path to The Tipping Point:

His mother and father

His inner Paavo Nurmi

His exposure to the realities of the often intimidating idiosyncrasy of academia

Born in England and raised in Canada, he is the son of a Graham Gladwell, a white math professor from Kent, England and Joyce Nation, a Jamaican born and bred therapist and writer. The Gladwell parental units met as students at University College, London, fell in love and got on with building their life together…stoically…all in the era of miscegenation hysteria.

Gladwell has written evocatively about being both white and black and thus neither black nor white. And of his general otherness growing up in Elmira, a Mennonite community in Waterloo, Ontario where his father taught at the University.

But when questions of “What are you?” arise as they did in his youth, Gladwell prefers to push them to the periphery.

As one might expect from his cerebral work, Gladwell kept to himself as a kid. He preferred to hang out at his father’s office at the University of Waterloo exploring its halls and libraries and carrels than putting in the hours at the local rink like his contemporaries.

While the first to admit that he hasn’t a clue of what his father’s work was all about, seeing the human beings behind the papers that filled the journals that lined the library shelves made him comfortable with PhDs and PhDs in training. The guy who spoke of Taylor and Maclaurin series’ like people today speak of the Kardashians and Jenners was his just his goofy dad, the same man who liked to go to Menonnite barn raisings or organize a group of kids in a game for entertainment. Having inside access to the humanity behind the scholarship demystified the ivory tower for Gladwell. It even made him fond of them.

Gladwell describes not playing hockey in his hometown as the equivalent of living in Munich and not drinking beer. Instead of mastering the slapshot, he ran. Not just for fun, but competitively.

His dedication and determination rewarded him with a victory in the 1500 meters (just about a mile) in the 1978 Ontario High School Championships. His time was 4 minutes 5 seconds…enough to beat the future Canadian record holder, David Reid.

A (The?) Defining Event of Gladwell’s Life

Imagine doing anything to the point where your heart cannot pump oxygenated blood fast enough to supply your body’s demand? For anyone who has ever had to run as fast as they could for a length not conducive for sprinting, Gladwell’s performance is stunning.

Running the middle distance requires the long view of a marathoner to set and maintain a pace, but also the nerve of Usain Bolt, a willingness to burn through all reserves in a final rush to the finish.

Running the 1500 meters will also answer a simple personal question.

How much stress and pain can you endure and still perform?

Gladwell found out of what stuff he was made at fourteen.

That’s a formational life victory. Before he wrote one word as a professional journalist, Gladwell knew how to press himself across a finish line.

After a desultory experience in college—he graduated with a History degree from Trinity College at the University of Ontario—Gladwell pursued an advertising career.

Every agency rejected him. He had none of the flash of an adman. Not even the potential of sizzle.

But with a 1982 summer internship from the National Journalism Center on his resume, he found a position as an assistant managing editor at the conservative magazine, American Spectator. A stint at Insight magazine and freelance work at The New Republic followed. In 1987, the The Washington Post beckoned and he’d made it to journalism’s big show.

As a sometime utility infielder though, not a front-page feature writing superstar.

Gladwell spent nine years and his oft-quoted ten thousand hours honing his craft covering business and science for the Post, rising to bureau chief of the New York office.

Then in 1996, the sizzle queen herself Tina Brown hired him as staff writer for The New Yorker, the equivalent of getting journalism tenure. He’s been there ever since.

The first piece Gladwell wrote for the magazine was called Blowup, which was categorized under The New Yorker rubric, “Department of Disputation.” A revelation story about accidents, it riffs on a theme that will become Gladwell’s bread and butter—what we accept as common sense wisdom is spectacularly inaccurate.

At the heart of Blowup, which explores the myriad of little “acceptable risks” inherent in big technological efforts like the risk of an O-ring failure during the launch of the space shuttle Discovery, is this sentence…

What caused the accident was the way minor events unexpectedly interacted to create a major problem.

In other words small things can have big effects.

His next extended piece, Black Like Them appears in the April 29, 1996 issue under “Personal History.” It tells the success story of his Jamaican cousin Rosie and her husband Noel over everyday racism. As they make their way in a New York suburb, the struggles American born blacks face in the very same neighborhood juxtaposes their travails. It ends with Gladwell recounting a meeting with a friend who did not know that his mother was Jamaican. His friend blames all that ails Toronto on the influx of West Indians into Canada…and it ends with these telling closing sentences:

In other words racism is not incredibly complicated. It is contextual. The same striving Jamaicans in New York upended and moved to Toronto would be viewed…overnight…as irredeemable gangsters.

The subtext of Black Like Them is that Racism is simply small-minded people spreading ignorant fallacies to explain away complex phenomena. It’s easier to blame someone else than to change the way you think and see the world.

Which begs additional questions: Is Groupthink of this sort as arbitrary and accidental as it seems to be intellectually lazy? Or are there ways to combat it?

At what point do small things, like an ignorant friend damning an entire group of people without knowing a single one of its members, critically compound to cause huge effects…one far larger than the sum of its parts?

That is, when exactly does the wear and tear on an O-ring move from an acceptable risk to an explosive failure? Or specifically, how many miserable people spouting nonsense does it take to penetrate and deposit their prejudice into the minds of others?

Gladwell’s next piece for The New Yorker will begin to explore these questions and set the stage for his 1.5 million dollar predicament.

October 25, 2017

Act Three is the Ninth Inning

How should your novel or screenplay finish?

It should end with the score tied in the bottom of the ninth and the base runner representing the winning run tearing about third base and highballing for home.

Rounding third and heading for home

Deep in right field, the outfielder with a rifle for an arm has just fielded the line drive that has sent our runner racing flat out. The outfielder slings the ball like a bullet toward home plate, where the catcher is waiting, eye on the throw, braced to receive the shock of the runner as he hurtles toward home.

At third base, the coach is waving frantically to the runner rounding the corner. Go! Go!

Every fan in the stadium is on his or her feet. Kids are going crazy. In the broadcast booth, the play-by-play announcer is losing his shit. The whole stadium is going insane.

Okay, maybe that’s not the WHOLE third act. We can screw the drama tight in the eighth inning with a couple of relievers coming in and getting knocked out of the box, a clutch homer or two, a drag bunt that gets beat out, maybe a wild pitch, a passed ball.

And we can ratchet the tension up even higher in the top of the ninth and then the bottom.

But at crunch time, if we want our game/novel/screenplay to have the fans screaming in their seats, EVERYTHING that went before has to build to that final moment of tension and suspense, and then we have to play that moment for all it’s worth.

Act Three of The Godfather has Michael Corleone “settling all family business” in one concentrated violent burst, i.e. murdering all the heads of the competing Five Families. But first his guys take out the traitor in their midst.

TESSIO

Can you help me, Tom? For old time’s sake?

TOM HAGEN

Can’t do it, Sally.

And the second betrayer, Connie’s husband Carlo Rizzi.

MICHAEL

Don’t tell you’re innocent, Carlo. Because it insults

my intelligence.

Pick any great play, novel, or movie from Hamlet to Breaking Bad, and Act Three is a rising crescendo, drawing upon every stitch of drama and conflict that has been set up through Act One and Act Two and paying it all off in one thunderous, do-or-die climax.

This is the architectural shape not only of a story but of a joke, a bar fight, a litigation, an election, and an act of love.

The ninth inning is not about nuance.

It’s about speed.

It’s about momentum.

The ninth inning is that runner hurtling around third, tearing down the line, and diving flat-out to beat the catcher’s tag at home.

[More in the next few weeks about Act Three and what makes it work or not work.]

October 20, 2017

You Have The Power

June 12, 1993, presented me with a question.

Go anchor or go springboard?

Let the day pull me deeper than the Mariana Trench or propel me beyond Hubble’s view?

I flip flopped for years.

Today I’m still in Hubble’s view, and it’s been years since I hung with the bottom feeders, but I look around me and see the same struggles.

I’ve written in the past that one key piece of advice that I’ve had for young artists is that they enroll in business classes, so that they can protect themselves from the wolves.

There’s something else: Be prepared to fight. There are people who will try to hurt you—and they don’t all reside in Hollywood.

Be prepared to fight today. Be prepared to fight tomorrow. Be prepared to fight every day that follows.

And if you cross paths with a rabid wolf, don’t let it steal your soul.

Hold on tight and fight.

Fight for your ideas.

Fight for your work.

Fight for your mind.

Fight for your body.

Fight for everything you hold dear.

At the time it might feel like they have the power, but remember your own power and use it.

Your mind. Your body. Your soul.

You have the power.

October 18, 2017

The Female Carries the Mystery

I’m re-reading one of my favorite books on writing, Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat! Goes To the Movies.

Blake Snyder (who died tragically at age 51 in 2009) was a screenwriter who did a lot of thinking about what makes a story work and what makes it not work. His first book, Save the Cat!, is a classic.

Bogey and Bacall in “The Big Sleep”

One of Blake Snyder’s writer-friendly inventions is what he called “BS2,” the Blake Snyder Beat Sheet.

The beat sheet broke a story—any story from the Iliad to La La Land—down into about sixteen “beats,” e.g. Opening Image, Theme Stated, Catalyst, Break into Two, etc.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot in the light of my ongoing “Reports from the Trenches” struggles.

I’m asking myself,

What am I learning through this process of rebuilding a story that has crashed?

How can I help others in the same straits?

What’s the Big Takeaway?

When you and I say that we “write instinctively,” what we mean is we trust our gut. That’s how we shape and flesh out our story. We might feel something like, “The story should be told by Character X, and not in memory but in the present.” Or, “Something’s missing in the middle. We need more with Characters Y and Z.”

What Blake Snyder was trying to do with his Beat Sheet (and what any good editor does, or what I myself am trying to do now with my Trenches project) is to formulize that process. Blake read a million novels and watched a million movies, and he concluded that the ones that work all follow certain timeless story principles or guidelines.

Sean Young in “Blade Runner” 1982

All stories that work have a similar shape, Blake believed. The specific one you or I might be working on at the moment will have its own unique shape. But it will cohere, in pretty predictable fashion, around the perennial “beats” of a narrative structure that has existed since our days of telling stories around the fire in the cave.

I agree.

Every story fits into a genre and every genre has conventions.

Here’s one I learned (I never knew this before) over the past five and half months beating my head against the wall on my police procedural/supernatural thriller.

The female carries the mystery.

(Sara Paretsky’s wonderful V.I. Warshawski notwithstanding, I’m speaking in the old-school idiom where the detective—Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, Rick Deckard—is a male.)

The above convention helped me enormously in reworking the story I was stuck on. I applied it and it worked.

What exactly do I mean by “the female carries the mystery?”

I mean that in a traditional detective story (which is what a police procedural is, even it’s set in the future like Blade Runner or Blade Runner 2049), the detective protagonist is usually following three threads as he drives the narrative forward:

Solve the crime/bring the villain to justice.

Unravel some inner personal conflict of his own.

Unearth the secret(s) of the female lead, with whom he has become emotionally involved.

There’s always a woman, and the woman always has a secret.

Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) in Chinatown.

Ruth Wonderly (Mary Astor) in The Maltese Falcon.

Helen Grayle (Charlotte Rampling) in Farewell, My Lovely.

The female can be a femme fatale or a damsel in distress.

Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity, Kathleen Turner in Body Heat, Lauren Bacall in The Big Sleep.

But the bottom line for the male detective/cop/lover is

Unravel the woman’s secret (“She’s my sister, she’s my daughter!”) and you solve the crime.

What I’m trying to say is that genre matters.

Conventions count.

Ryan Gosling in “Blade Runner 2049”

The story principles that work in other stories will work in yours and mine too.

And

Maybe the reason ours is not working is that we’re either violating a convention or we don’t even know it exists and so we’ve left it out.

I like the way Blake Snyder thinks because he looks to timeless storytelling principles and tries not to ignore them or to blow them off but to respect them and enlist them in our own story’s cause.

I haven’t seen Blade Runner 2049 yet, but for sure the female’s secret in the 1982 original (Rachel [Sean Young] is a replicant and in desperate need of help because of that) is central to that plot and to Rick Deckard’s (Harrison Ford) actions throughout.

October 13, 2017

It Ain’t Easy When You Get What You “Want”

What’s it like when you get the call? When you get the big deal and you’ve been ushered into Big Publishing’s Finishing School with a seven figure advance for your first book? Let’s head back to some material from www.storygrid.com and explore the reality of this dream come true state of being…

When contemplating a writing project, let just one question guide you:

What’s at stake?

Not just what’s at stake in the Story—if it’s not earth shaking, find another one to tell—but what’s at stake for you personally. If you could skip the project and forget about it the next day, it’s not one to devote years of your life to telling. Burning your creative days on something that’s not going to push you to the edge of madness is a waste of time.

You won’t get better. You’ll sell yourself short. No matter how popular or how well praised the finished product is, you’ll know that you phoned it in. So don’t do it. Press yourself.

Listen to what your insides are telling you to avoid…that’s the voice of Resistance. And as Steve Pressfield points out, you need to drive headlong into that negative storm. Use it as a guide to tell you what to do next.

If you keep hearing from the chattering monkey inside your head that doing X project is a stupid idea…that no one will care…that you could make an ass out of yourself…that you need to focus on something more practical…and on and on… That’s the one you need to work on.

Today, any of us can write and publish a book. I can’t emphasize how much of a gift that is. You don’t need me to tell you that you’re worthy to get your ideas into the world. You just have to choose yourself, do the work, and to hell with what I think.

Those age old external constraints no longer exist. Barriers to enter publishing’s retail marketplace were torn down almost ten years ago. We can write our stuff, upload it to an eBook seller, print on demand company and even audio publishing companies and have our multi platform work for sale on Amazon.com, iTunes, Kobo, Barnes and Noble, Ingram and on and on. And no one will tell us “no.”

We can’t decry I’m a genius, but no one will give me a chance anymore.

There are a million guides out there that will walk you through the process. It’s not more difficult than making a very good cake from scratch. It’s hard, but doable.

So why don’t we?

It is the internal constraints to writing our book (little discussed but more powerful than Vladimir Putin) that make us shudder and keep us on the sidelines.

Fear. Fear of criticism. Fear of failure. But mostly, the one we can all use to trump advice givers like me…Fear of poverty. Of putting in years of blood, sweat and tears and getting nothing in return.

Let’s be practical.

A fella needs to eat, doesn’t he? And if he’s married and has kids, he has to contribute to the family bank account. Even Maslow puts those necessities before personal self-actualization on his hierarchy of needs.

This is the humdinger Resistance throw down of them all. It shuts up anyone telling you to pursue something with no immediate or guaranteed payoff.

That’s nice, but how do I make my mortgage payments while I confront my internal demons and paint my masterpiece?

But what if you were guaranteed a return?

Then you’d do it, right? No sweat. Bring on the madness.

What if a publisher called you and said they’d agree to pay you 1.5 million dollars to write your book, no matter what? They’d sign a contract stating that even if not one person bought your book, you’d still get that 1.5 million. In fact they’d hand you $375,000 just for signing the contract. You know, as some seed money to get you started.

There would just be one catch.

They would have to read your book after you delivered it and determine whether it was “editorially acceptable,” which is code for whether or not they agree that it is worth that 1.5 million dollars.

I mean you didn’t think you could turn in a bunch of rubbish and expect 1.5 million dollars in return, right? Of course not.

And if they thought what you delivered did not live up to what you promised, well, you have to give them back the $375,000 they lent you to get your started.

No hard feelings. You tried, but didn’t quite make it. It happens.

And the kicker is that even if you disagreed with them and had great arguments to support your case, there is no outside third party—no certified editorial appraiser—who would be able to come in and “objectively” evaluate your manuscript. One man’s literary gold is another’s lead.

So because they are the one’s fronting the costs to create the thing, the publisher’s subjective opinion reigns. He who writes the check makes the rules. That’s the way it works rube.

This is why so many writers don’t exhale until they’ve officially had their manuscripts “accepted.” Until they are, Damocles’ sword hangs over them.

Malcolm Gladwell was in this precarious place back in 1998. We last left him as he stared down the mess of material on his desk—the stuff that he’d have to somehow piece together into a first draft of his book The Tipping Point.

Sitting with his morning coffee, you know these realities had to have run through his mind.

A confluence of events came together in such a way that the external barriers to being published were not just removed for him; they were put in his service. This was back in the day when the only way into a bookstore (brick and mortar or online) was through the front door of a publisher.

He got the big deal. The seven-figure contract that we read about over and over again as if it is some sort of winning ticket. It’s not. It’s the biggest mind-fucker there is.

Especially for nonfiction writers who sell their work on proposal.

Here’s why:

Big money can lead you to do one of two things:

Play it safe.

Again, most nonfiction writers sell their work on proposal. A proposal is a thirty or more page document that walks an editor/publisher through a future work. It opens with a prologue or introduction that reads “as if” it were the future book itself. And then it outlines the intentions of the writer…why this project is important, why the writer wants to write it, why he or she is the perfect one to write it etc.

There is an art to creating an irresistible proposal. And a danger too.

If your proposal makes promises you cannot reasonably keep, you will panic when the time comes to write your first draft…if not before.

So what many writers do is to suggest that there could be great payoffs to what they propose, but they make sure not to go “too far.” They manage expectations of the editors and publishers who read their proposals and when the time comes to write their first drafts, they use the proposal as their fail-safe security blanket.

That is, they deliver what they’ve promised in the proposal, but not more. When they deliver their draft a year or so after it has been commissioned, they do not risk a reaction like “ummm, this is interesting, but it’s nothing like the proposal that we bought…”

Those words from an editor are the precursor to “so we’re going to have to cancel this contract…here is the address to send back your check for the signing advance.”

Swing for the Fences

A big deal can also have the opposite effect. Instead of the nonfiction writer playing it safe, he may find himself tempted to go for broke…to invent a wild new idiom or dive into material that he is not fully conversant.

He doesn’t look at the work as a way to hone his particular genius, to push the edge of his skill set, instead, he decides that what he can do with what he’s done in the past is not enough. If he’s a journalist, he decides that he needs to emphasize his line-by-line writing. If he’s an accomplished stylist, he decides that he should do more “on the ground” interviewing or research. He abandons his particular craft and tries to learn a new one instantly.

In his darkest hour, he convinces himself that what he can deliver with what he has at his disposal (his craft) is not good enough. It is not worth seven figures. So he has to “reinvent” himself and find a way to be a writer worth the big bucks.

Sitting with his coffee all those years ago, Malcolm Gladwell must have weighed both of these options.

He chose a third option…He would play it safe and swing for the fences.

October 11, 2017

Giving Myself Some Props

Okay, it’s done.

Today I wrap Draft #14 of the project that’s been kicking my butt and send it in to Shawn.

Jurgen Prochnow as the skipper in “Das Boot”

Will it fly? We’ll see. But for the moment (a short moment), my job becomes about self-validation, i.e. giving myself some props.

These “Reports from the Trenches” have been going on now for five and a half months. That means I’ve been rewriting a crashed-and-burned manuscript for that long.

Good job, Steve! Whatever happens, you have risen to the occasion. You have performed like a pro. You did not crap out (okay, maybe you whined and sniveled a little) and you did not go into the tank. Half a warm beer for you!

But seriously …

Who else is gonna give you and me a pat on the back if we don’t do it ourselves? Our spouse maybe. Our agent. A good friend or two.

Their kind words are valid and much appreciated.

But the thing is … they don’t know. They can’t really. The only one who really knows is you and me.

Remember the training sequence in the first Rocky? With the theme music, “Flying High Now,” in the background as Rocky completes his final sprint up the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum? That was great. It was stirring. You had to love it.

But in the real word, what would’ve happened was Rocky would have gone from there to a preliminary bout, stepped into the ring, and been kayoed in the first round by some ham-and-egg fighter that nobody, including Rocky, had every heard of.

THEN the real work would’ve started.

Back to gulping those six raw eggs at four-thirty on a freezing winter morning. Back to jogging through the flower market, racing along the wharf, and punching frozen sides of beef in Pauly’s meat locker.

Do it all again, the second time. Without the theme music.

Can you do that? Have you done it? I take my hat off to you. That thankless, glamourless passage is the difference between being an amateur and being a pro.

Rocky woulda done it. And you and I would too.

It may seem silly to give ourselves kudos. It may seem vain and even a little preposterous. But this, like the work itself, is the difference between being an amateur and being a pro.

One of my favorite scenes in a movie (and the source of the “half a warm beer” reference) comes from Wolfgang Petersen’s great submarine film, Das Boot. Have you seen it? About a German U-boat in WWII? A young war correspondent (meant to be the audience’s window into the film) is just joining the seasoned crew of a submarine about to put out to sea. The sub has been refitting in port for several weeks; the crew has been laboring non-stop; the at-sea shakedown has been completed … the vessel is ready to set forth. The crew assembles on deck. A young lieutenant serves as a guide and escort to the correspondent. The captain, played by Jurgen Prochnow, finally appears.

YOUNG LIEUTENANT

(to correspondent)

Now comes the speech.

The skipper steps up before the men.

CAPTAIN

Now, men. Everything set?

The crew shouts “Yes, sir.” The captain smiles, nods, and turns to board the vessel.

YOUNG LIEUTENANT

(to correspondent)

Some speech, huh?

And he too hustles off to board the sub.

That’s my idea of self-validation. Between you-and-me and you-and-me.

We know.

We understand.

It’s enough.