Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 39

August 14, 2019

The Female Protects the Mystery

We said in last week’s post, speaking of novels or films with characters of both sexes, that

The female carries the mystery.

Faye Dunaway as Evelyn Mulwray in “Chinatown”

This principle, true as it is, is not enough to make a story work. In addition

The female protects the mystery.

Every story has a secret. Every tale has a meaning, an interpretation of depth.

The protagonist’s role (either a male, or a female acting in a “male” capacity) is to uncover that secret.

In Robert Towne’s script of Chinatown, the protagonist is private eye Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson). His role in the drama is to get to the bottom of the “case”—to find out who murdered Hollis Mulwray, who hired him (Jake) and put him on this case, and what greater, deeper, more hideous crimes these first two issues conceal.

Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) is Jake’s client. She is the character who carries the mystery. She knows the answers to all these questions.

And, critically important for the story, she conceals them.

Evelyn knows what Jake, at the start, doesn’t. She knows the crimes her father Noah Cross (John Huston) has committed. She knows the further, even more despicable crime he’s trying to commit in the present.

For her own reasons—primarily to protect her daughter Catherine, but also to shield her own shame—Evelyn will resist to her final breath revealing these secrets.

For us as storytellers, this is exactly what we want.

We want in our stories a character who conceals the tale’s secret—i.e., its theme, its metaphor, its meaning—and who will do anything to maintain that secret.

Why do we want that? Because it provides powerful, drama-producing obstacles for our protagonist to overcome.

In some stories, like Chinatown, the female who carries the mystery knows what the mystery is. She’s aware of it. She’s deliberately concealing it.

In others, the “female” carrying the mystery doesn’t know it at all. She’s blind to it. She’s ignorant of it.

Dr. Ana Stelline (Carla Juri), the memory-maker in Blade Runner 2049, is unaware that she is the daughter of Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) and Rachael (Sean Young) and that she is thus the “miracle” that proves that replicants can reproduce and therefore possess souls and have hope for the future.

Carla Juri as memory-maker Dr. Ana Stelline in “Blade Runner 2049”

She carries the mystery but is unaware of it.

Likewise Cathy Whitaker (Julianne Moore) in Far From Heaven is utterly clueless to the mystery of self-delusion and willful blindness that she carries.

This obliviousness works in story terms in both cases because it serves the same narrative purpose as Evelyn Mulwray’s conscious concealment—it keeps the protagonists (K [Ryan Gosling] in Blade Runner 2049; in Far From Heaven, Cathy Whitaker herself) laboring against powerful obstacles throughout the story to unravel the mystery.

A third category of mystery-carriers (and mystery-protectors) consists of primal or societal forces like the sea in Moby Dick or the farmers’ rice fields in Seven Samurai. Though these are not literally female, they are so metaphorically.

These also work story-wise because they cannot reveal their mystery. They are the mystery.

The takeaway for you and me as storytellers is that

One character in our drama must carry the story’s secret

and that character—for reasons of conscious will, ignorance, or incapacity—must present a monumental obstacle to the uncovering of that secret.

The female carries the mystery

And

The female protects the mystery.

August 7, 2019

The Female Carries the Mystery

I’ve got a new book coming from W.W. Norton in November. It’s a novel called 36 Righteous Men. If you followed last year the series on this blog called “Report from the Trenches,” you know the details of the huge crash this book took, midstream in its writing, and of my six months of nonstop hell trying to regroup, restructure, and reanimate it.

Barbara Stanwyck as the fatal female in “Double Indemnity”

The concept that saved the day came from Shawn Coyne’s editorial notes:

The female carries the mystery.

This is a helluva deep subject and one that, even now, I have only the sketchiest and most tenuous handle on. Bear with me please. I’m gonna try, in the next few posts, to plunge into this topic and see if we can extract a kernel or two of wisdom.

What does it mean, “The female carries the mystery?”

It’s not hard to see in a movie like Chinatown, where the character of Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) is literally the woman of mystery, or in Double Indemnity, where Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) fulfills the same narrative purpose.

In both films—and just about every other film noir or detective story you or I can think of—the female lead has a secret she is hiding from the male lead (and from the world in general, including, at least partially, herself.)

The story is about finding out that secret.

Only when that secret is revealed does the movie deliver its knockout dramatic and thematic punch.

EVELYN MULWRAY

She’s my sister! She’s my daughter!

or

PHYLLIS DIETRICHSON

I’m rotten, Walter. Rotten to the heart.

But the idea that the female carries the mystery can be applied, I believe, even to novels and movies that literally have no female characters.

In Moby Dick, the female is the ocean.

The unplumbed, unknowable depths of the sea, into which the whale plunges, taking Ahab with him.

The eternal, unfathomable sea is the female.

In Seven Samurai, the flooded rice fields are the female. They are the well of fertility, the source of life. They are in fact what all the heroism and slaughter were about. They were the stakes of the story. They were the mystery.

Remember the final scene of Kurosawa’s all-time classic, when the villagers, to the beat of the communal tom-toms, replant their now-preserved fields while the surviving samurai can only watch and move on? That’s the mystery revealed.

Even in a story without human female characters, like Akira Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai,” the female still carries the mystery

In my book, 36 Righteous Men, the central female character is a defrocked rabbi named Rachel Davidson.

In the first version of the novel—the one that crashed—I had Rachel indeed bearing the mystery (in other words, she knew all the details of the occult understory) but I had her trying deliberately and passionately to reveal this mystery.

Huge mistake.

Only when Shawn pointed out the error was I able to regroup and reconceive the story, at least as far as Rachel was concerned.

The change I made was to make her carry the mystery and hang onto it for dear life.

In other words, I turned every scene with Rachel on its head. Instead of having her seek to reveal, I had her seek to conceal.

It worked.

It made the other primary characters—two NYPD homicide detectives, a man and woman—dig deeper and harder. It made them do real detective work. It tripled the power of Rachel, and it supercharged the villain, whom Rachel was now covering for instead of trying to reveal.

I’ve been working on a new book for the past year—a totally different story, in another century and another genre. But the principle

The female carries the mystery

remains foremost in my working mind. I have stayed hyperconscious (and conscientious) at every stage—conception, construction, and the scene-by-scene writing—of who the “female” is, what mystery she carries, and how I can maintain that mystery and enhance it through Act One, Act Two, and Act Three to build to its maximum emotional impact in the climax.

July 31, 2019

The Villain Doesn’t Change, Part Two

It’s unfortunate that the term “McGuffin”—meaning that thing that the Villain wants—sounds so dopey.

Kevin Costner and Susan Sarandon in Ron Shelton’s “Bull Durham”

Unfortunate because there’s a lot of meat to this idea.

I suspect Alfred Hitchcock, the person we associate most with the term McGuffin, wanted the name to sound silly. In his mind it didn’t matter what the McGuffin was—the nuclear codes, the letters of transit, the briefcase in Pulp Fiction. All that mattered for him was that the villain wanted it.

But the idea that the villain wants something—that he or she has an object of desire—is a topic worth examining in greater detail.

We’ve said in previous posts that

The villain never changes.

And further that

If the villain were capable of change, he’d be the hero.

Another way of putting this is that

The McGuffin never changes.

The villain wants the same thing at the end of the story as he or she did at the start.

King Herod wanted to kill the baby Jesus.

Niander Wallace (Jared Leto) in Blade Runner 2049 wanted to kill the baby replicant.

Vic Hoskins (Vincent D’Onofrio) in Jurassic World wanted to weaponize the baby velociraptors.

We’ll never know of course, but it’s a pretty good bet that King Herod was not capable of waking up in the middle of the night and declaring, “Gee, this is a bad idea, killing all the innocents in Judea. Let me summon my generals and rescind that order.”

The villain never changes because what he/she wants never changes.

On the other hand, let’s consider the hero.

The hero does change

And

The hero is capable of wanting something different at the end of the story than he or she did at the start.

In fact you could make a strong case that the hero MUST change her or his want … that, in fact, that’s what makes her or him a hero.

Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) in The Silence of the Lambs goes from wanting to be a good little FBI agent to wanting to come into her own as an independent individual.

Cathy Whitaker (Julianne Moore) in Far from Heaven goes from wanting to be a good wife and proper suburbanite to wanting to find out who she really is and what her real best life ought to be.

Crash Davis (Kevin Costner) in Bull Durham goes from wanting to keep playing ball as long as he can (and being a cool single dude) to wanting to make it to the majors as a manager (and bring Annie Savoy [Susan Sarandon] along.)

In other words, it isn’t just that

The villain does not change

while

The hero does change.

It’s that what the Villain wants doesn’t change, while what the hero wants does.

July 24, 2019

The Kind of Crazy We Want

We said in a previous post, “Pick the idea that’s craziest.”

Nicolas Cage and Cher in “Moonstruck”

But what exactly do we mean by “crazy?”

Here’s what we DON’T mean:

We don’t mean pick a prospective project that’s ridiculous or absurd or so weird or personal or self-indulgent that there’s no chance of it finding an audience.

What we do mean is,

Free your thinking from conventionality.

Don’t second-guess your potential readers, and especially don’t think down to them.

Don’t pick the idea you imagine they’ll like, or believe they’ll respond to.

Pick the idea you like, even if (especially if) it doesn’t seem commercial.

By “crazy,” we also mean

Pick an idea that seems beyond you.

Choose something that makes your palms sweat. When Charles Lindbergh told his friends in 1926 that he intended to fly the Atlantic solo, I’m sure no few responded, “Charlie, that’s crazy!”

That’s the kind of crazy we want.

That’s good-crazy.

That’s smart-crazy.

That’s bold-crazy, audacious-crazy, stretch-the-boundaries crazy.

Did you see the movie Moonstruck? There’s a great line in the script by John Patrick Shanley delivered by Nicolas Cage as “Ronnie Cammareri” to Cher as “Loretta Castorini.”

RONNIE

You’re gonna marry my brother? Why you wanna sell your life short? Playing it safe is just about the dangerous thing a woman like you can do.

Amen.

Work outside the lines.

Go for good-crazy.

July 17, 2019

The Life We’ve Chosen

I’m gonna take a tiny break from our mini-series about Villains to share a blog post from my friend Seth Godin.

Why? Because I think Seth has described in a few short lines the Writer’s Life (or any artist’s life) in a way that nails it like nothing I’ve ever seen. Seth’s blog, by the way, is my go-to. It’s the first one I read every morning. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

Seth Godin. Nobody better.

THE SOLO MARATHON

The usual marathons, the popular ones, are done in a group.

They have a start time.

A finish line.

A way to qualify.

A route.

A crowd.

And a date announced a year in advance.

Mostly, they have excitement, energy and peer pressure.

The other kind of marathon is one that anyone can run, any day of the year. Put on your sneakers, run out the door and come back 26 miles later. These are rare.

It’s worth noting that much of what we do in creating a project, launching a business or developing a career is a lot closer to the second kind of marathon.

No wonder it’s so difficult.

This is our life, yours and mine. I would add only two thoughts:

One, the long-form writer’s life (whether she’s writing fiction, nonfiction, TV, movies, whatever) is not just one marathon … and not just a marathon without spectators or Gatorade along the roadside or a sponsor or a ribbon and a medal at the end.

It’s one marathon after another.

Finish one, start another.

It’s marathoning as a way of life. As life itself.

And two, for me anyway, I wouldn’t want to live any other way.

I thank heaven every day that I don’t have to go to a job or report to a boss or have anyone or anything telling me what I can and cannot do.

I love the marathoning life.

I love to start on one overwhelming (to me) killer project and see it through, no matter what it takes, to the end.

I love finishing one and starting the next.

Oh, there’s a third thing.

An interviewer asked me the other day if I ever got lonely writing. I answered immediately, “No.” (In other words, I don’t mind at all that there are no spectactors lining the race course, or lists of finishers in the newspaper, etc.)

I’m never lonely writing because I’m with my characters.

Who better to run a race with? Not against them but alongside them.

The solo marathon life is the life for me.

July 10, 2019

The Non-Zero-Sum Character

Here, in no particular order, is a sampling of real-life non-zero-sum characters.

Jesus of Nazareth

The 300 Spartans at Thermopylae

Joan of Arc

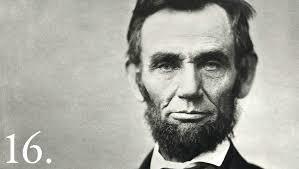

Abraham Lincoln

A non-zero-sum kinda guy

Mahatma Gandhi

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

John F. Kennedy

Malcolm X

Robert Kennedy

John Lennon

Yitzhak Rabin

And a few from fiction and motion pictures:

Odysseus

Beowulf

Atticus Finch

Huckleberry Finn

Celie in The Color Purple

Rick Blaine in Casablanca

Pike, Dutch, and the Gortch Brothers in The Wild Bunch

Captain Miller (Tom Hanks) in Saving Private Ryan

Shane

Travis Bickle

Princess Leia

Luke Skywalker

If the Villain believes in a zero-sum world, the Hero believes in its opposite.

If the Villain believes in a universe of scarcity, the Hero believes, if not in a world of abundance, then at least in the possibility of such a world.

If the Villain believes in a reality dominated by fear, the Hero believes in one ruled by love.

The Villain is cynical. He or she believes that mankind is inherently evil. The Villain believes in “reality,” in a Hobbesian world of all-against-all.

The Villain is not necessarily “bad” or even “villainous.” In the villain’s eyes, he is the Good Guy. He is simply acting and making choices within a universe of monsters. He must therefore become, in the name of Good (or at least self-preservation or the preservation of those dear to him) a monster himself.

The zero-sum view of life is that of limited resources. Not enough to go around. If you and I want our share (or even simply enough to survive), we must take it from somebody else. However much of the pie we grab, that’s how much less remains for everyone else.

In the non-zero-sum world, on the other hand, resources are infinite. The love a mother gives to her child (and that the child returns) grows greater, the more each loves. There is and can never be a shortage of love.

Compassion is infinite.

Integrity is infinite.

Faith is infinite.

Zero-sum versus non-zero-sum. Which point of view do you believe?

July 3, 2019

The Villain Speech in “Vice”

We said in last week’s post that the Villain sees the world as a zero-sum game.

This is a corollary to another aspect of the classic antagonist’s view of life as a war of all-against-all. To re-quote Colonel Nathan Jessup (Jack Nicholson) from Aaron Sorkin’s A Few Good Men:

COLONEL JESSUP

Son, we live in a world that has walls, and those walls have to be guarded by men with guns. Who’s gonna do it? You? … I have neither the time nor the inclination to explain myself to a man who rises and sleeps under the blanket of the very freedom that I provide and then questions the manner in which I provide it!

This is the exact POV that the filmmakers of Vice (written and directed by Adam McKay) give to their protagonist villain, Dick Cheney. In the final scene of the film, the VP is being interviewed for television.

Christian Bale as Vice President Dick Cheney in “Vice”

REPORTER

Two-thirds of Americans believe the Iraq War was not worth fighting. They’re looking at the value gained versus the cost in American lives and Iraqi lives.

CHENEY

So?

This quote, as I understand it, is literally true. The real Dick Cheney really did say it. If so, it is world-class Movie Villain material, worthy of Dr. No or Dr. Strangelove.

But the filmmakers don’t stop here. They use this line to jump off from, into a fuller expression of the Villain’s point of view. They have Cheney turn slowly toward the camera until he “breaks the fourth wall” and addresses the audience directly.

REPORTER

So, don’t you care what the American people think?

CHENEY

I think you … uh … cannot be … uh … blown off-course. (Sighs, turns further to speak directly to the audience). I can feel your recriminations and your judgment … and I am fine with them. You wanna be loved. You wanna be a movie star. The world is as you find it. You have to deal with that reality. There are monsters in this world. We saw three thousand innocent people burned to death by those monsters. And yet you object when I refuse to kiss those monsters on the cheek and say “Pretty please.” You answer me this: what terrorist attack would you have let go forward so you wouldn’t seem like a mean and nasty fella? I will not apologize for keeping your family safe and I will not apologize for doing what needed to be done so that your loved ones can sleep peaceably at night. (Sighs). It has been my honor to be your servant. You chose me. I did what you asked.

I confess I’ve always had a soft spot for Dick Cheney. The point of view he articulates (and that he acted upon and unrepentantly holds to this day) certainly cannot be called inaccurate or untrue to certain “realities” of the world and of human nature. Caesar would have echoed this view of life, as would have Alexander and Napoleon and scores of other real-life champions to whom we erect equestrian statues—and with good cause.

But this point of view—however practical, “realistic,” or even necessary in a Hobbesian world—is the point of view of the Villain.

Here’s Cliff Robertson as CIA officer Higgins in Three Days of the Condor, justifying to Joseph Turner (Robert Redford) a secret American plan to invade Saudi Arabia and seize the oil fields:

Robert Redford and Cliff Robertson in “Three Days of the Condor”

HIGGINS

Today it’s oil, right? In ten or fifteen years, food. Plutonium. Maybe even sooner. Now, what do you think the people are gonna want us to do then?

TURNER

Ask then.

HIGGINS

Not now—then! Ask ’em when they’re running out. Ask ’em when there’s no heat in their homes and they’re cold. Ask ’em when their engines stop. Ask ’em when people who have never known hunger start going hungry. You wanna know something? They won’t want us to ask ’em. They’ll just want us to get it for ’em!

(We’ll dig a little deeper into this—and consider the nature of the non-zero-sum character, the Hero—in the next few posts.)

June 26, 2019

To the Villain, It’s a Zero-Sum Game

The definition of a zero-sum game is if one side wins, the other side loses.

Whatever proportion of goodies Player A takes, by that exact amount is Player B’s stake diminished.

Paul Bettany as Will Emerson in “Margin Call”

In a zero-sum equation, if I take a slice of the pie, there’s that much less for you.

This is the how the Villain in our stories sees the world.

In Margin Call, written and directed by J.C. Chandor, the executives at a major investment bank realize, over one long dramatic night, that their trading model is fatally flawed. The instant “the Street” gets word of this, the firm will implode—unless these same execs can somehow offload the contaminated securities before potential buyers realize they’re worthless.

Oh, I almost forgot. This act, should the dastards pull it off, will produce the most catastrophic market crash since 1929.

Paul Bettany plays “Will Emerson,” one of the firm’s senior officers. He is asked by a pair of younger execs, played by Zachary Quinto and Penn Badgley, if such a stunt is even technically possible.

WILL EMERSON

You can’t … it’s impossible. But they’ll figure out a way. I’ve been at this place for ten years and I’ve seen some things that you wouldn’t believe. When all is said and done, they don’t lose money. They don’t care if everyone else does, but they won’t.

That’s zero-sum thinking.

If the creek runs dry in Shane, either the villainous cattleman or the vulnerable homesteaders lose. No other outcome is possible.

In The Revenant, it’s Leonardo DiCaprio versus Tom Hardy. In One-Eyed Jacks, it’s Karl Malden against Marlon Brando. Only one can win. Every James Bond film, every sci-fi monster pic, every comic book and superhero saga is zero-sum, at least in the eyes of the villain.

In Margin Call, Kevin Spacey plays sales manager Sam Rogers, one of the few characters possessed of a glimmer of conscience. In a critical four-in-the-morning meeting, he confronts the firm’s CEO John Tuld, played by Jeremy Irons.

SAM ROGERS

The real question is: Who are we selling this to?

JOHN TULD

The same people we’ve been selling it to for the last two years, and whoever else would buy it.

SAM ROGERS

But John, if you do this, you will kill the market for years. It’s over. And you’re selling something that you know has no value.

JOHN TULD

We are selling to willing buyers at the current fair market price. So that WE MAY SURVIVE!

Jeremy Irons as CEO John Tuld

The Villain believes in a world of scarcity. His point of view is predicated upon the notion that if he is to survive and even prosper, he must take from you and me. No other equation exists for him. He cannot conceive of any other world.

Here’s gangster Johnny Rocco (a brilliant Edward G. Robinson) to ex-Major Frank McCloud (Humphrey Bogart) in John Huston and Richard Brooks’ Key Largo.

FRANK MCCLOUD

I’ll tell you what he [Rocco] wants.

JOHNNY ROCCO

Go ahead, soldier. You tell ’em.

FRANK MCCLOUD

He wants more.

JOHNNY ROCCO

That’s it, soldier! More! I want more!

Marine Colonel Nathan Jessup (Jack Nicholson) in Aaron Sorkin’s A Few Good Men understands that point of view exactly. Here he is on the witness stand facing off against Navy prosecutor Daniel Kaffee, played by Tom Cruise.

COLONEL JESSUP

Son, we live in a world that has walls, and those walls have to be guarded by men with guns. Who’s gonna do it? You? … I have neither the time nor the inclination to explain myself to a man who rises and sleeps under the blanket of the very freedom that I provide and then questions the manner in which I provide it!

Is life really zero-sum? Is this truly the way the world works?

The hero doesn’t think so.

The protagonist in most (but not all, be it said) novels and movies is the character who is capable of a non-zero-sum answer.

We’ll examine this in greater detail over the next few weeks.

June 19, 2019

Pulp Heroes

I was watching the movie Logan on TV last night. Do you know it? It’s one of the X-Men flicks, starring Hugh Jackman as “the Wolverine,” though in this story he’s the more human-ish version of that character, called “Logan.”

Hugh Jackman as the pulp hero in “Logan”

I’ve actually watched this movie about ten times. A lot of writers would turn up their noses at this species of pulp-y fare, but I really love it … and I learn a lot because these are the kinds of stories that work.

The heroes work.

The villains work.

The stories work.

I was studying the character of Logan/Wolverine. It was crystal-clear that he was drawn in the tradition of dozens of other male/adventure leads—Bogart in Casablanca, Han Solo in Star Wars, Clint Eastwood in anything, not to mention the male leads in Seven Samurai, Shane, The Searchers, The Wild Bunch, Paper Moon, True Grit, Guardians of the Galaxy, The Book of Eli, every Bourne movie, etc.

Each of these protagonists is dealing with a split in his interior nature—a division that, as I see it, is common maybe not to real-life males in every culture but certainly to most in Western societies, particularly our own good ol’ U.S.A.

The split is between darkness and light, between wariness of and self-distancing from others and opening one’s heart to love.

Dafne Keen as Laura in “Logan”

If I had the Logan script in front of me, I could scroll down and pick out at least a dozen places where the character of Logan articulates some version of

LOGAN

Leave me alone, I can’t help you

or

LOGAN

It’s none of my business, get the hell outa here

or Bogey’s character of Rick Blaine in Casablanca declaring, “I stick my neck out for nobody” or “I’m the only cause I’m fighting for.” Etc., etc.

The male protagonists in virtually all the stories cited above and ten thousand others have all undergone painful, deeply disillusioning experiences of life. Maybe in childhood, maybe in love, maybe in war. They’ve all arrived at some form of solitary gunslinger persona.

Then there’s the other half of their character.

The “good” half.

In almost every such tale, a “B” story character, often female, but sometimes a child (as in Paper Moon or True Grit) or a helpless person or persons in need (the prostitutes of Big Whiskey, Wyoming in Unforgiven, the villagers in Seven Samurai) crosses paths with our detached, remote hero.

The question each story asks is, “Will our hero stand up only for himself? Or will he open his heart to another?”

Why do these stories all work?

Because in many ways this question is the dilemma we all face.

Is the world a Hobbesian, zero-sum nightmare, a war of all against all, in which the only realistic course is to look out for Number One?

Or is love and compassion for the Other the truly brave and noble choice in a world where the forces of darkness and self-interest seem to be everywhere ascendant?

In Logan, the “love interest” is a young mutant girl named Laura, who shares with Logan the Wolverine claws (not to mention his DNA).

The character of Logan goes from rejecting her and distancing himself from her predicament (she’s in life-and-death danger) to … well, I won’t ruin it for you.

The heroes in all the stories above take Choice #2.

I don’t think it’s just a pulp choice.

I think it’s the human choice, whether the protagonist is Jesus of Nazareth or the 300 Spartans or Gandhi or Martin Luther King.

The hero chooses love.

He chooses to sacrifice his own selfish needs for the good of the Other.

June 11, 2019

The Blank Page is Not Neutral

It seems so harmless, doesn’t it? A simple sheet of 8 1/2-by-11 bond that you and I roll into our typewriter (or the equivalent empty screen on our laptop.)

What could possibly go wrong?

The blank page can be a pretty scary place.

(Other than terminal procrastination, paralysis by perfectionism, self-doubt, self-loathing, self-recrimination, self-hatred, not to mention terminal existential dread, panic, hysteria, flatulence, bad breath, dandruff, and the uncontrollable desire to drink, smoke, vape, fly to Katmandu, and have a mad self-destructive affair with the first person that says hello.)

The blank page is not neutral.

If we think of it in combat terms, that empty sheet is the equivalent of Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944 from the Allied side. Waiting for us when we wade ashore are bunkers, pillboxes, minefields, barbed wire, machine gun nests. Artillery and mortar fire will be pounding every inch of the beach without letup. Even if you and I make it ashore in one piece, nothing lies ahead of us inland but dug-in enemy divisions backed up by tanks and aircraft, on and on.

Or, if we’d rather see it in Game of Thrones terms, that blank page is defended by the Night King, the army of the dead in numbers uncountable, not to mention a dive-bombing, fire-breathing dragon whose jetting flames have got our name on them.

What can we do to fight this?

Step One (and a tremendously powerful step) is simply to be aware of the fact of Resistance and to not be unnerved and unmanned when it rears its hideous head.

What could possibly go wrong?

My own life was a train wreck for seven years after its first encounter with this monster. Why? Because I wasn’t mentally prepared. I was innocent.

I had no defenses.

No plan of action.

Resistance steamrolled right over me.

The blank page is not neutral.

On the other hand …

On the other hand, simply to know what’s coming makes all the difference.

When we know what we’re up against, we can formulate a plan.

We can steel ourselves in advance.

We can marshal our internal resources.

Then, when that first Mike Tyson left hook slams into our jaw, we may reel, we may stagger, we may even hit the canvas …

But it won’t necessarily kayo us.

The blank page is not neutral, but neither are we.

Dragons have been slain.

The Allies did prevail on D-Day.

Even the army of the dead eventually bit the dust.

We will find a way, we will do what we must … whatever works for you, whatever works for me.

The blank page is not invincible.