Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 40

June 5, 2019

The Gods Rule by Acclaim

Did you see Oliver Stone’s 2004 movie, Alexander, about Alexander the Great? Indeed it was not one of Mr. Stone’s best, as I suspect he himself would admit if we got him drunk enough.

Colin Farrell in the title role of Oliver Stone’s “Alexander”

But the film did have a great one-sheet promo line:

Fortune favors the bold.

(The phrase comes from a Latin proverb, variously rendered as audentes Fortuna iuvat and Fortuna audaces iuvat among others.)

Here’s a true story of Alexander from Diodorus and other ancient sources:

When he was preparing to march out from Macedonia to commence his assault on the Persian Empire, Alexander called the entire army together, officers and men, for a great festival at a place called Dium on the Magnesian coast.

When all the army had assembled, Alexander began giving away everything he owned. To his generals he gave great country estates (all properties of the Crown); he gave timberlands to his colonels and fishing grounds, mining concessions and hunting preservers to his midrank officers. Every sergeant got a farm; even privates received cottages and pasturelands and cattle. By the climax of this extraordinary evening, his soldiers were begging their king to stop. “What,” one of his friends asked, “will you keep for yourself?” “My hopes,” said Alexander.

When you and I launch ourselves upon a new book or screenplay or videogame or TV series, we are like Alexander.

We are invoking Fortune (a goddess, remember, and thus divine), just as he did.

And we must do it like he did.

Here’s another way of putting it:

If you build it, he will come.

Or another:

L’audace! L’audace! Toujours l’audace!

In other words, the bigger the idea, the bolder the venture, the better.

Write what you don’t know.

Pick the idea that’s craziest.

Write the book you can’t write.

Alexander believed that the gods rule not by power but by acclaim. Remember that for all the great conqueror’s rationality (his tutor as a boy, after all, was Aristotle) he remained at heart a wild northern highlander and a warrior of primal, even primitive origins. The gods were not fancies to him. They existed. They were real.

Man bows before the immortals, Alexander believed, because of their greatness, their beauty, their transcendent majesty. Beholding Athena or Apollo (or even demi-gods like Herakles and Achilles) we humans have no choice but to respond with awe and veneration … and to follow and obey, if these beings should so charge us.

But Alexander drew a further corollary from this faith.

He believed that the gods would take our side if only we acted with enough courage, audacity, and defiance of death. In other words if we acted like them.

Alexander believed that we mortals could compel heaven’s intercession by our own actions, if they possessed sufficient thrasytes, boldness, and andreia, martial valor.

Not only would the gods intercede in such cases, but they had no choice.

Why did Alexander—not the myth but the actual historical man—lead his Companion cavalry from the very front in their charge at the enemy? Why did he wear a double-plumed helmet and distinctive armor, so he could be recognized at any distance on the field?

Yes, he took the lead to act as an example. To fire his men to emulate his valor.

But more critically, to his mind, Alexander was acting for an audience on Olympus.

He believed that when heaven beheld him aboard his warhorse Bucephalus striking the foe before any other, it would be powerless to resist interceding in his aid.

“Fortune favors the bold” is a mighty truth, even if it can’t be proven empirically in a laboratory or on a blackboard by mathematics.

Start before you’re ready.

Write what you don’t know.

Pick the idea that’s craziest.

Write the book you can’t write.

May 29, 2019

“B” Speaks for “A”

Quick announcement…

For years, people have asked me, “When are you going to do an in-person speaking gig about The War of Art, Resistance, etc.?” I’ve always said no. But a part of me never stopped thinking, “Well, maybe one day … “

Short version: That day has come.

It’ll be an intimate event, informal, just one day — September 15 in Nashville. I’m going to talk about the artist’s inner world (or at least my own), the self-discipline, the source of creativity, and the interior war that we all have to fight to bring our books and ideas into the world. I’ll do a morning on that and an afternoon taking questions and just seeing where the mutual conversation goes.

We’re only making 35 spots available and I’m not sure if I’ll ever do this sort of event again.

Click here to see more details and I’ll see you in September.

The Western genre presents a number of unique problems for us as writers.

Jean Arthur as Marian in “Shane”

First is the convention that most of the characters in a Western are men (or women) of few words. The strong silent type.

In a Western (and in cop stories and thrillers and even many love stories), we in the audience get few Shakespearean soliloquys.

BUTCH

How long you figure we’ve been waiting?

SUNDANCE

A while.

BUTCH

How much longer you think we have to wait?

SUNDANCE

While longer.

For sure in many of these genres, our hero (or most other characters) is never going to have a moment when he or she breaks down and reveals in intense emotional detail the reason he or she is a) a killer, b) a broken soul, or c) a mangy, low-down, lying skunk.

This leaves us as writers with a problem, to which we have a limited number of solutions.

One, the character reveals him or herself in clipped, terse, oblique dialogue.

Two, the character reveals him or herself in action.

Nothing wrong with either of these. (In fact, it’s great discipline for us as writers to have to limit ourselves to these options.)

But there’s a third way.

A different character speaks for our character.

The writers in Shane use this over and over, and it works every time. In one early scene, Marian (Jean Arthur) is putting her six-year-old son Joey (Brandon deWilde) to bed after a day in which Shane has stood up bravely for Joey’s father, Joe Starrett (Van Heflin.)

LITTLE JOE (BRANDON DEWILDE)

Ma, don’t you just love Shane? I think, next to Pa, I love him more than anybody! Don’t you just love him?

Brandon deWilde as Joey and Alan Ladd as Shane

The writers do this again in a scene between Shane (Alan Ladd) and the villainous cattleman Rufe Ryker (Emile Meyer). The moment takes place in town, in Grafton’s General Store. Ryker knows Shane is a gunfighter. He can’t figure out why he’s working as a low-paid ranch hand for sodbuster Joe Starrett.

RYKER

You don’t belong on the end of shovel.

Ryker offers to double Shane’s pay if he’ll come work for him. Shane turns him down.

RYKER

What are you lookin’ for?

SHANE

Nothing.

RYKER

Pretty wife Starrett’s got …

Or again with little Joe in the final scene as Shane rides away.

LITTLE JOE

Pa’s got work for you, Shane! And mother wants you. I know she does!

But the greatest moment in Shane of one character speaking for another comes in a scene between the stalwart, honorable homesteader Joe Starrett and his wife Marian. The scene takes place in the kitchen of their little cabin. It’s night, just minutes from the climax of the story. Joe, who’s a brave man but no gunslinger, is about to ride into town to face the professional gunfighter Wilson (Jack Palance) who has been hired by the evil cattlemen to run Joe and his fellow homesteaders off their claims.

In the audience we know Joe doesn’t stand a chance against Wilson.

He is riding to certain death.

Marian has been pleading with Joe desperately and passionately not to go.

MARIAN

(with intense emotion)

Don’t I mean anything to you, Joe? Doesn’t Joey?

JOE

Honey, it’s because you mean so much to me that I’ve got to go.

Joe explains that he could never face Marian again as her husband and protector and the father of their son if he “showed yellow” in this critical moment.

JOE

I know I’m kinda slow sometimes. But I see things. And I know if anything happened to me that you’d be took care of. You’d be took care of, better than I could do it myself. I never thought I’d live to hear myself say that … but I guess now’s a pretty good time to lay things bare.

Marian buries her face in her hands and breaks down.

In all three of these moments, other characters speak for Marian.

It’s tremendously powerful and effective.

But they all build to the moment when Marian herself speaks for another character. In this ultimate moment, which follows the previous bit of dialogue almost immediately, Shane has fought Joe hand-to-hand to prevent him from riding into town to face Wilson. Shane has knocked Joe unconscious with a blow from his six-gun. Instead Shane will face Wilson.

In this scene Joe lies on the ground in Marian’s arms, woozy and virtually unconscious. Clearly Marian realizes that Shane, by taking on the fight in town, is giving up the last of his dreams. Win or lose, he is sacrificing everything. Marian has not spoken to Shane through the whole movie of her own thoughts or emotions about him … nor has he said a word about his for her.

MARIAN

You were through with gunfighting.

Shane answers with only, “I changed my mind.” Marian absorbs this with profound empathy and grief.

MARIAN

Shane, are you doing this for me?

What’s great about this manner of conveying emotion is that even in this climactic moment, neither character speaks for her or himself. Instead, either one character verbalizes the other’s emotions or he or she responds to the other in the simplest, least overtly emotional way.

What gives this its power is it makes you and me in the audience figure it out on our own. It makes us participate. No expression in the script is “on the nose,” i.e. relayed overtly by the character about his or her own feelings. Everything is indirect or conveyed in response (or non-response) to something expressed by another.

It works here in a Western. More importantly, it works in this Western as love story, which is, in the end, the most emotional type of drama we can write.

Character “B” speaks for Character “A.”

May 22, 2019

The Villain Wants the McGuffin

“McGuffin” is a term primarily associated with movies (Alfred Hitchcock is usually credited with inventing—or naming—it), but the concept applies with equal effectiveness to prose fiction and even nonfiction.

Edward G. Robinson tells Bogey what he wants in “Key Largo”

The McGuffin is what the villain wants.

The granddaddy of McGuffins is the Holy Grail in Arthurian legend. Closer to home it’s the letters of transit in Casablanca, the suitcase in Pulp Fiction, the Maltese Falcon, the Ark of the Covenant. R2D2 is the McGuffin in Star Wars, according to George Lucas.

Here’s the McGuffin’s origin story from a 1966 interview with Hitchcock by Francois Truffaut (also explained by Hitch in a 1939 lecture at Columbia University):

“It might be a Scottish name, taken from a story about two men in a train. One man says, ‘What’s that package up there in the baggage rack?’ And the other answers, ‘Oh that’s a McGuffin.’ The first one asks ‘What’s a McGuffin?’ ‘Well’ the other man says, ‘It’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands.’ The first man says, ‘But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands,’ and the other one answers ‘Well, then that’s no McGuffin!’ So you see, a McGuffin is nothing at all.”

Let’s dig a little deeper into this device and see what light it can shed on the nature of villainy in any story.

We said in several earlier posts that

The villain never changes.

Only the hero changes. We quoted a wise old Hollywood producer:

“If the villain could change, he’d be the hero.”

This idea takes us straight back to the nature of the McGuffin. Remember Hitchcock’s final thought in his definition:

“So you see, a McGuffin is nothing at all.”

Put another way,

It doesn’t matter what the McGuffin is. All that matters is that the villain wants it.

Or another, possibly deeper way:

The ideal McGuffin is one that is deliberately meaningless or even silly. Because this makes the point that the villain’s greed and covetousness is everything.

Did you ever see Key Largo, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall (directed by John Huston and written by Huston and Richard Brooks) with a great Edward G. Robinson as the gangster “Johnnie Rocco?” Rocco is on the run with his gang of cutthroats, hiding out while he waits for a contact from Miami and a boat to Cuba. An approaching hurricane maroons the bad guys in the Hotel Largo (an ideal confined space for a drama), where they live out a long, fraught night with several denizens of the establishment including Ms. Bacall and Bogey as Frank McCloud, a recently discharged WWII major who chances to be in Key Largo visiting the family of a comrade killed in the war.

In the movie’s most memorable scene, one of the captives, in distress at the seeming senselessness of Rocco’s greed and villainy, demands of the gangster, “What is it you want?”

For a moment Rocco is non-plussed. He can’t come up with an answer.

Bogey as Maj. McCloud offers to supply it.

MCCLOUD

I’ll tell you what he wants.

ROCCO

Go ahead, soldier. Tell him.

MCCLOUD

He wants “more.”

For a moment the gangster seems almost insulted by this. Then he slaps his thigh and laughs.

ROCCO

That’s it, soldier! More! I want more!

The villain, in other words, barely even knows what he wants.

“What” means nothing.

“Wants” is everything.

The Alien wants to feed and kill. So does the shark in Jaws or the Thing in The Thing. Or the pods from space in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Zombies want to eat your brain. Viruses want to contaminate you. The creature in the Species series wants to mate with you and mutate.

The point of Hitchcock’s McGuffin—that its content is essentially meaningless, that all that matters is that it be an object of desire—is to illustrate the nature of villainy and evil itself.

Villainy’s object is molecular, cellular, visceral. It seeks only to dominate and to self-perpetuate. Nothing grander. Nothing more meaningful.

The villain wants the McGuffin.

May 15, 2019

Write the Book You Can’t Write

I know (from letters and e-mails sent in) that many readers of this blog are published writers, even multiply-published writers, as well as successful artists and entrepreneurs of all kinds.

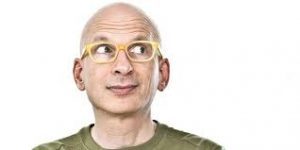

Seth Godin, post-Yoyodyne

If you’re one of them (and even if you aren’t), for sure you can look back on certain successes you’ve had and say to yourself,

“How did I ever do that?”

How did I write Braveheart? Where did I find the guts to launch Yoyodyne?

Two answers come to mind.

“I was so desperate I had no other choice”

Or

“I was too dumb to know I couldn’t do it.”

Either one of those is a fabulous place for an artist to be. (It might not feel like it at the time, but it is.)

Consider what it means when we stand on the threshold of a new project and think to ourselves, “This is way too big for me. I can never pull this off. It’s so far out of my league it’s ridiculous.”

Whose voice is that?

It’s not our voice.

It’s the voice of Resistance.

Recall one of the Cardinal Truths of Resistance:

The greater a new project’s importance to the positive evolution of our soul, the more Resistance we will experience to attempting it.

In other words, when the voice in our heads tells us we can never achieve such a bold aspirational venture, what it really means is:

Yes, we can.

If the dream were not possible for us, Resistance would never feel the need to bomb us with megatons of negativity.

Resistance, remember, understands our capacities far better than we do.

It knows we can fly the Atlantic solo. It knows we can reach the South Pole by dog sled. It knows we can make it to the moon and back.

That’s why it feels the need to marshal all its resources to convince us we can’t.

I wrote in The War of Art,

The counterfeit artist is wildly self-confident. The real one is scared to death.

Take Resistance’s word for it.

When it tells us we can’t, it means we can.

Write the book you can’t write.

May 8, 2019

Write What You Don’t Know, Part Two

One of my earliest mentors was a writer named Paul Rink. (He’s on pages 111 and 112 in The War of Art.)

Emilia Clarke as Daenerys Targaryen

Before I knew him, Paul lived in Big Sur. This was during the time when Henry Miller was a major personality there. Their families lived on Partington Ridge. Every morning Paul used to shepherd the children of the neighborhood down to the school bus stop on Highway One. He stayed with them till the bus came.

To pass the time, Paul had a game he played with the kids (You can read about this in Henry Miller’s Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch.) Paul would tell them a story that carried on from day to day. He made up the plot on the spot. Paul would get his hero into unbearable, cliff-hanging fixes. The deal with the kids was that if at any time they couldn’t stand the suspense, they could call out the magic word—“Inchconnecticut!”—and that would save the hero.

Paul would surreptitiously glance up the highway till he saw the school bus approaching. Then he would crank up the suspense so that the kids were just about to cry out, “Inchconnecticut!” (They didn’t want to, of course, because that would end the story for the day.) Then at the last excruciating moment, Paul would say, “Ah, here’s the bus. We’ll pick up the tale tomorrow.”

The kids would all groan. But they couldn’t wait for the next day to get back to the saga.

(In Big Sur, Henry Miller has “Inchconnecticut” as two words. Not so! Paul declares it was always one.)

All this is long way of saying again

Write what you don’t know.

Paul didn’t know what was coming next in his story. He didn’t lie awake the night before plotting out the tale for the next day.

He winged it.

Paul entered that magical realm wherein dwell improv comedians, off-the-cuff banquet speakers … and you and me.

Writers of fiction.

One other entity abides in this favored province.

The goddess.

The Muse.

I asked Paul if he every ran out of hair-raising predicaments to get his bus stop characters into.

“Never,” he said. “Some twist would always occur to me.”

When George R.R. Martin started with Daenerys Targaryen, he had no idea who she would turn out to be or what adventures she would have. How could he? There was no Daenerys Targaryen.

What did he do?

He made it up.

He wrote what he didn’t know.

And, sure enough, from some mysterious quadrant of the imagination, from some dimension of reality that has nothing to do with reason or logic or rationality, a brilliant, charming, scary, funny, heart-stopping saga unfolded.

If George R.R. can do it, so can you and I. (As George R.R. would be the first to testify.)

The field is identical for us as it is for him.

The goddess will fill our outstretched palms just as she filled his.

All we have to do is show up and

Write what we don’t know.

May 1, 2019

Write What You Don’t Know

The classic axiom cited to young writers starting out is

Write what you know.

George R.R. Martin wrote what he didn’t know

Makes sense, right? If you’ve just returned from sailing alone around the world, write that story. If you’re a surgeon, a single mom, an opioid survivor … write about that.

Write what you know.

My theory is a little different. Like the other principles in this series, it’s counter-intuitive. It doesn’t seem to make sense.

But, as we’ve seen, sometimes sense is nonsense.

Logic and rationality rarely jibe with the unknowable intangibles of creativity.

My mantra for myself is

Write what you don’t know.

When I started Gates of Fire, I knew absolutely nothing about the ancient Spartans. (Okay, maybe a little.) Same with Last of the Amazons. Same with Killing Rommel.

Even The War of Art was a flyer for me.

Here’s what happens when you write what you don’t know.

The Muse enters the picture.

Consider Game of Thrones, or its literary progenitor from George R.R. Martin, A Song of Ice and Fire.

Imagine we’re George R.R. rolling the first blank sheet into the typewriter.

We peck out one word: Westeros.

Add a family name: the Lannisters.

Another, the Targaryens.

George R.R. may have been versed in pre-medieval English history and literature (and that certainly would have helped) but, my goodness, didn’t the Muse plunge in for him and light up the board?

There was no way George R.R. could “know” Cersei Lannister or Jon Snow or Tyrion Lannister. The novelist and the filmmakers had to kiss caution goodbye and let their imaginations take flight.

The result has held millions spellbound for almost a decade.

When we write what we don’t know, we have no choice but to surrender control.

Good things happen when we do that.

When we write what we don’t know, we station ourselves at the interface between the known and the unknown.

That is a place of wizardry.

A place of power.

Forces far beyond our ken are summoned to this power point by our need and our will and our aspiration and our intention. Inspiration appears. The unborn and the unexpected step forth. Speeches pop from our characters’ mouths that we could not have written if we’d toiled all night or all winter. Our princesses acquire a wardrobe, an arsenal, even a language never before seen.

How does this happen?

Who’s in charge here?

It’s not us, that’s for sure. Or if it is us, we’re helping only a little.

There’s a word for this process.

It’s called fiction.

It’s called fun.

It happens, always, when we write what we don’t know.

April 24, 2019

A “Save the Cat” Moment

If you’ve read many of these posts, you know that I’m a big fan of screenwriting guru Blake Snyder and his book on the film writer’s craft, Save the Cat. Here is Blake defining this principle:

Save the Cat is the screenwriting rule that says: “The hero has to do something when we meet him so that we like him and want him to win.” Does this mean that every movie we see has to have some scene in it where the hero gives a buck to a blind man in order to get us onboard? Well no, because that’s only part of the definition.

Alan Ladd as Shane establishes tension in a “Save the Cat” moment with Brandon deWilde as Joey

So on behalf of my hypercritical critics, allow me a mid-course addition [Snyder goes on to cite Quentin Tarantino’s intro scenes in Pulp Fiction, in which the killers Vincent and Jules (John Travolta and Samuel Jackson) are without redeeming moral virtues but at least are funny and charming]: The adjunct to Save the Cat says: “A screenwriter must be mindful of getting the audience ‘in sync’ with the plight of the hero from the very start.”

Let’s examine this concept (which applies equally well, I believe, to the writing of novels and all other forms of storytelling).

Consider the opening of the classic 1953 Western, Shane.

The hero Shane (Alan Ladd) enters a Wyoming valley on horseback. He’s alone, riding at an easy, unhurried pace. He approaches a homestead. Six-year-old Joey (Brandon deWilde), the child of this ranch, keenly observes Shane’s approach.

From the rider’s buckskin-fringed jacket and the .44 on his hip, we—and Joey—realize at once that the stranger makes his living with a gun.

The filmmakers now have a problem. How can they get us in the audience on the side of a professional killer?

One item in their favor: they have cast Alan Ladd as Shane. He’s handsome, likeable. But he’s still packing that Big Iron on his hip. What if we in the audience perceive him as a Bad Guy? If we lose sympathy with him here at the very beginning, it could be fatal for the success of the story.

Here’s how director George Stevens and writers A.B. Guthrie, Jr. and Jack Schaeffer handled this issue.

Shane rides up slowly to where Joey is watching him. The boy is sitting on the top rail of a corral fence. Shane pulls his horse up alongside Joey and reins-in. A few words of greeting are exchanged between the man and the boy’s father Joe Starrett (Van Heflin), but nothing (yet) that gives us or Joey a clue as to whether this stranger is a good guy or a bad guy.

Then Shane turns to little Joey.

SHANE

Hello, boy.

Joey drops his eyes. He’s shy … and more than a bit spooked by the stranger.

SHANE

You were watchin’ me down the trail for quite a spell, weren’t you?

Joey withdraws even further. He’s frightened. Is the stranger going to take offense at the boy’s intrusiveness? Will he rebuke him or treat him with dismissively or with condescension?

JOEY

Yes, I was.

Shane’s expression softens. He leans forward in the saddle, toward Joey.

SHANE

You know, I … I like a man who watches things going on around. It means he’ll make his mark someday.

In that instant, Joey surrenders completely to this stranger. In the audience so do we.

We don’t know what Shane’s issues will turn out to be, or what struggles he will be facing in the story, but already we are rooting for him and hoping he will prevail.

But the key element, to me, of a Save the Cat moment is that it must cut against the grain. The character who delivers it must be someone who, on initial impression at least, is an individual possessed of elements of darkness.

When hard-boiled Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) in Casablanca acts with kindness toward a young couple fleeing the Nazis, or when cynical private eye Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson) in Chinatown lets a hard-pressed client off on a bill, the act does something more than say, “He’s a nice guy.”

It creates a personality.

It sets up two poles of character that are in dynamic conflict with one another.

It hooks us because we want to learn which side will win.

More on this next week.

April 17, 2019

Pick the Idea That’s Craziest

Sometimes you and I as writers will see a whole menu of ideas before us.

One will seem surefire commercial. Another will seem risky but fun. A third might seem totally off the wall.

Dick Rowe, “the Man Who Turned Down the Beatles”

Which one should we pick?

Before I give you my own idiosyncratic answer (which you’ve probably guessed already), let me cite two instances from my own career.

The idea for The Legend of Bagger Vance came to me just as my screenwriting career, which I had dedicated ten years of my life to, was about to catch fire. The idea came as a book, not a movie. My agent fired me over it. He thought I was crazy to do it.

It turned out to be the first genuine success of my career.

The idea for Gates of Fire seemed (to me, as I considered plunging in to write it) even less commercial. It seemed absolutely loony. An epic about warriors from 2500 years ago, from a country nobody has heard of, fighting in a battle no one can remember, in a place no one can spell, let alone pronounce.

Gates has sold over a million copies and is still going strong.

For me, the craziest, least likely ideas have always worked out the best.

Why?

Here’s my theory:

Because these ideas weren’t crazy at all.

They only seemed crazy to me, at their inception, because I was thinking with my head.

The sphere of creativity does not operate by the same laws as that of normal, conventional enterprises.

I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again:

You and I as artists have no idea what we’re doing.

We may think we do. We may imagine that we understand what the zeitgeist is calling for. We may believe that we are manipulating our material with clear-eyed, conscious control.

We’re not.

What is really happening is this:

You and I as artists inhabit one dimension of reality—the material dimension.

Meanwhile:

All creativity has its origin in a different sphere—the plane of potentiality.

Our job is to tune in to that sphere. And to trust it.

What seems “crazy” to us on our level is not crazy at all on the higher level. In fact it’s the opposite of crazy. It’s exactly what needs to be expressed and what needs to be heard.

Cubism.

Quantum mechanics.

E = MC2..

Do we want to be the guy who turned down the Beatles? (When we ourselves are the Beatles?)

Sometimes it’s crazier to pick the conventional idea than it is to go with the craziest.

P.S. In Dick Rowe’s defense (he was Head of A&R at Decca Records in the 50s, 60s, and 70s), he did sign The Rolling Stones, the Moody Blues, the Zombies, and many, many more.

April 10, 2019

Start Before You’re Ready

We feel a book inside us. It’s there. We see the characters, we feel the structure, we sense the contours. We just need another week/month/semester to get our heads in the right place to begin …

William Hutchison Murray, author of “The Scottish Himalayan Expedition”

Start before you’re ready.

Forget that week.

Strike that month.

Start now.

Don’t wait till your ducks are in a row. Dive in now.

Why does this seemingly irrational principle work?

Because the sphere of invention operates by different (and higher) laws than that of normal, conventional enterprises.

The Muse works by her timetable, not ours.

When the train leaves the station, you and I had better be on it.

Or consider this corollary:

Go to the station. The train will appear.

Many of the principles that work for us as artists are counter-intuitive. They make no sense in the world of logic and rationality, but they are spot-on in the quantum sphere of creativity. Here is William Hutchison Murray from The Scottish Himalayan Expedition.

Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative and creation, there is one elementary truth the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves too.

I quoted this passage in The War of Art seventeen years ago. Its brilliance (and its truth) remains undiminished.

All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision [to begin], raising in one’s favour all manner of unforeseen incidents, meetings and material assistance which no man could have dreamed would have come his way.

I have learned a deep respect for one of Goethe’s couplets:

“Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it.

Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it. Begin it now!”

That book/screenplay/business venture that we feel inside us? We may think we’re not ready. We’re wrong.

The goddess is at work within us.

Trust her.

Start before you’re ready.

April 3, 2019

The First Page

There’s a terrific book that I often recommend to young writers—The First Five Pages by Noah Lukeman. Mr. Lukeman is a long-time agent, editor, and publisher. The thrust of his counsel is this:

You gotta come outa the blocks FAST

Most agents and editors make up their minds about submissions within the first five pages. If they spot a single amateur mistake (excess adjectives, “your” instead of “you’re,” “it’s” instead of “its”), your manuscript goes straight into the trash.

Grind on those first five pages, says Mr. Lukeman. Make certain they are flawless.

I would go further. The make-or-break page, to my mind, is Page One. Even more critical: Paragraph One.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness …

The first paragraph, the first sentence is do-or-die. It has to be more than just free of error. It has to kick ass.

All happy families resemble one another; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

Those two opening sentences are from A Tale of Two Cities and Anna Karenina. I’ve abbreviated them to show that they still work, even when they’re cut off. A great opening can hook a reader in as few as three words.

Call me Ishmael.

Nor does a riveting opening have to be particularly literary, or display masterful erudition, or inform the reader that the hero of the tale has just woken up to discover that he has been turned overnight into a cockroach.

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all that before they had me, and all the David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

I think of Page One as a battlefield or a stage for seduction. The contest is between the writer and the reader.

We have to win that battle, you and I, and we have to win it fast. We have to complete this seduction by Paragraph One, and certainly no later that Paragraph Two.

Here’s one trick. Start at the very beginning of your book and read down till you get to a sentence, or a run of sentences, that possess genuine magic. Then look back at the sentences that precede them. Can these sentences be cut? Cut them!

The legend is that Maxwell Perkins convinced Ernest Hemingway to get rid of the first two chapters of The Sun Also Rises. Not sentences or paragraphs. Chapters. He cut them till he got to this, at the start of what was originally Chapter Three.

Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton. Do not think that I am very much impressed with that as a boxing title, but it meant a lot to Cohn. He cared nothing for boxing; in fact he disliked it. But he learned it painfully and thoroughly to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he had felt on being treated as a Jew at Princeton. There was a certain inner comfort in knowing that he could knock down anyone who was snooty to him, although, being very shy and a thoroughly nice boy, he never fought except in the gym.

Never take the reader’s attention for granted. We have to earn it, you and I, and that ain’t easy. What we want is for the reader to stop resisting. She must trust us. She must believe us. She must surrender to us.

If you can do that in the first paragraph or the first page, there’s a good chance she’ll hang on for the whole E-ticket ride.