Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 38

October 23, 2019

A Prayer to the Muse

The first thing I do when I enter my office each morning is to say a prayer to the Muse.

I say it out loud in dead earnest.

The prayer I say (this is in The War of Art, page 119) is the invocation of the Muse from Homer’s Odyssey, translation by T.E. Lawrence, the Oxford-educated classical scholar also known as Lawrence of Arabia.

When he wasn’t leading the Arab Revolt of WWI, T.E. Lawrence found time to do a little translating

We were speaking last week about conceiving of our office/studio as a sacred space.

For me, this prayer is part of that process.

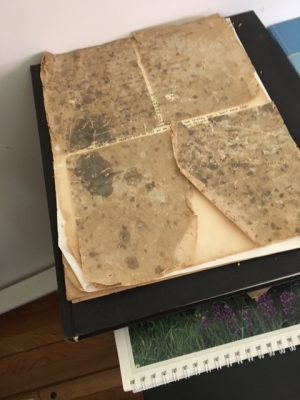

The prayer was given to me by one of my first writing mentors, Paul Rink. He typed it out and gave it to me. I still have it. The paper is slowly crumbling. It looks like an artifact from Lara Croft, Tomb Raider.

But the prayer itself is indelible, and it’s for real.

I say it each morning before I sit down to work because I know, as every artist who will tell the truth knows, that “I” am not the source of any of the work I produce.

The work comes through me from another plane.

I’m the conduit.

I’m the human voice.

But the source lies elsewhere.

I can’t compel the work to appear.

I can’t make the goddess deliver.

I can’t bribe her, or coerce her, or grovel before her, or make her any pledges or promises that will induce her to do what I wish.

I can only invoke her.

That’s what Homer was doing when he began the Odyssey with these verses:

The original typed version of the Prayer to the Muse, given to me by Paul Rink. (It was new once.)

O, Divine Poesy,

Goddess, daughter of Zeus,

sustain for me this song …

He did the same in the Iliad, with

Sing, goddess,

of the wrath of Achilles, Peleus’ son …

If someone were following me around on a working day, she might think I was a little nutty. Certainly if she looked inside my head and saw the way I was conceiving the activities of each morning—from getting up and brushing my teeth to going to the gym to crossing the threshold of my office—she’d be forgiven if she thought, This dude is off in airy-fairy land.

But I’m not.

I’m living in the absolute real world—the world of the mystery of creation, which no one understands and no one ever will.

I’m doing my work the same way the crypt carvers of Petra did theirs, or the musicians in the court of Louis the XIVth, or Hemingway and Gertrude Stein in Paris in 1921.

I’m doing it the same way Homer did, and by the same rules.

October 16, 2019

A Sacred Space

When I was eight years old, my family spent part of a summer vacation visiting friends in New England. One of the grownups we spent time with was a painter. He had a big sunny studio out behind his house, just past trellises groaning under the weight of roses and through a little wattle-type gate.

I remember the artist’s wife telling me and my brother, “Don’t ever go in there without Peter’s permission.”

The studio is a sacred space.

Of course Peter gave his permission all the time. He was happy to have kids around. Sometimes we would even take naps in the studio.

One thing we were always careful of, though, was not to make noise.

And not to distract Peter when he was working.

His studio was a sacred space.

Later, when I studied martial arts, the sensei insisted that his students stop and bow as they crossed the threshold of the dojo—to him as our teacher and to the space itself.

It too was sacred.

My own office is just a converted bedroom in my house. It’s got nothing particularly esoteric in it, except maybe my lucky toy cannon that fires inspiration into me, or perhaps my lucky horseshoe from Keeneland Race Course in Lexington, Kentucky.

But it’s a sacred space too.

I’ve made it sacred by the work I’ve done there and by the attitude of respect and devotion that I bring with me when I enter. Kids can come in. Animals can hang out. But they have to be respectful too, as I and my brother were when we crossed the doorstep of Peter the painter’s studio.

My friend and mentor David Leddick tells of when he was a young ballet dancer in New York and how his teacher instructed her students, before entering the studio where they were about to work,

“Leave your problems outside.”

She meant, “Leave your ego, leave your greed, leave your competitiveness with your rivals, leave your fear and your self-doubt and your lack of belief in yourself.”

Leave everything profane outside.

My cannon

In here, in this space where we work, there is no room for such stuff.

Here, the goddess dwells.

(Or at least we hope she’ll stop briefly by.)

We must enter this space without dirt on our feet or mundane aspirations in our hearts.

My friend Ed Hinman feels that way about the gym. Ed is a gonzo weight guy (he’s writing a book called Drawn to Iron) who sees resistance training the way yogis see yoga or renunciants see a week-long sesshin.

The word Ed uses is “portal.”

I like that a lot.

Through this space, Ed believes, we pass by dint of effort and dedication and commitment onto and into a nobler plane of reality.

This is my world too—and my attitude—when I enter the converted bedroom that is my office and turn my little toy cannon so its muzzle faces me, ready to fire.

October 9, 2019

“Get Up! Begin Your Day!”

I’m a gym person.

I have been for thirty years.

I go early.

Ridiculously early.

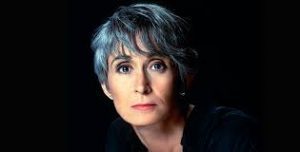

Twyla Tharp does too. Here she is from The Creative Habit:

Choreographer Twyla Tharp begins her day at the gym

I begin each day of my life with a ritual. I wake up at 5:30 A.M., put on my workout clothes, my leg warmers, my sweatshirts, and my hat. I walk outside my Manhattan home, hail a taxi, and tell the driver to take me to the Pumping Iron gym at 91st Street and First Avenue, where I work out for two hours. The ritual is not the stretching and the weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go I have completed the ritual.

What we’re talking about here is Resistance.

Not Resistance to physical exercise.

Resistance to our artistic calling.

Twyla Tharp does her lunges and stretches for their own sake, yes. But they are also (and more importantly), as she says, a ritual.

They are preparation for the moment when she arrives at her dance studio and faces the choreographer’s equivalent of the blank page.

Her time at the gym is rehearsal for that moment.

It’s practice.

It’s preparation.

If you saw me in the squat rack at Gold’s Gym in Venice at five-thirty in the morning you might think, “Why is that guy busting his butt? He’s not gonna be running the marathon. What could he possibly be thinking? He ain’t gonna be starting next season for the Winnipeg Blue Bombers.”

Like Twyla, I am enacting a ritual.

I am rehearsing doing something I don’t want to do.

I’m rehearsing doing something I’m afraid of.

I’m rehearsing doing something that hurts.

When I hit the showers after my workout, I feel good. I’m proud of myself. I have faced another dawn when I could have lain in bed or blown off my journey or given in to some vice or distraction.

But I didn’t.

I have performed my ritual.

I have gotten my day started.

I have momentum now.

I can meet my buddies for breakfast, shoot the breeze for a while, then go home and get to work.

October 2, 2019

Resistance Wakes Up With Me

People ask me sometimes, “When in your day do you first feel Resistance?”

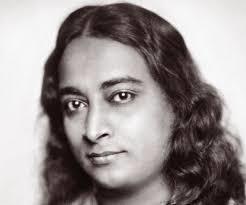

Paramahansa Yogananda did not lie in bed in the morning

My answer:

“The instant I open my eyes.”

In fact maybe sooner.

Maybe before I even know I’m awake.

I feel it.

It’s like Resistance is this huge, rapacious bear that sleeps in bed at my shoulder. By the time my feet hit the floor, it’s already lacing up its shoelaces.

Resistance is waiting for me.

He’s wide awake.

He’s ready to rumble.

He does not give me .0001 second of slack.

What’s the answer?

What’s my answer?

The only way I’ve found to beat this bear is to tackle him head-on from Microsecond One.

I get up.

I stagger to the bathroom.

I’m grumbling, I’m muttering to myself, I’m waiting (miserably) for the first positive thought.

But in my mind I have set myself to face that bear and beat him.

I was listening to a tape once of Paramahansa Yogananda. He was talking about what he does first thing in the morning.

Get up! Do not lie there ‘thinking.’ Nothing good every came from that. Get up! Begin your day!

When Yogananda says “thinking,” I know exactly what he means. He means the voice of the Resistance.

We think we’re “thinking.” We imagine that the stream of consciousness in our heads is cognitive ratiocination.

It ain’t.

It’s Resistance.

Every one of those “thoughts” is trying to get us to put off our work, to blow off our calling, to give up on ourselves and our destiny … just for the next few minutes, just till the clock hits seven, just for this one day.

Resistance wakes up with us.

It is relentless, merciless, pitiless, insidious. It cannot be reasoned with or appealed to. It takes no vacations and no holidays. It’s there on Christmas and it’s there on Kwanzaa.

We must accept this.

This is our calling.

It’s the life we’ve chosen.

Get up! Do not lie there “thinking.” Nothing good ever came from that. Get up! Begin your day!

September 25, 2019

The Villain Has No Empathy

“Empathy” is a term much in the news these days. It means of course that capacity of imagination that allows one person to feel another’s pain and to identify with, or even act in sympathy with, that other person.

If you and I as writers want to create a memorable villain, we will banish that capacity from our Bad Guy’s character.

Jeremy Irons as Wall Street CEO John Tuld in “Margin Call”

The Alien feels no empathy.

The Predator feels no empathy.

The pods in Invasion of the Body Snatchers feel no empathy.

Each acts only in its own self-interest.

Margin Call is one of my favorite movies of the past few years. Its villain, Wall Street CEO John Tuld (Jeremy Irons) is about as perfectly realized a villain as it is possible to create. (Kudos to Mr. Irons and to writer and director J.C. Chandor).

Here is Tuld in a scene with Sales Manager Sam Rogers (Kevin Spacey) justifying ruining thousands of his firm’s clients, not to mention tanking the entire global economy, by unloading under false pretenses a few zillion dollars in worthless securities.

SAM ROGERS

The real question is: Who are we selling this to?

JOHN TULD

The same people we’ve been selling it to for the last two years, and whoever else would buy it.

SAM ROGERS

But, John, if you do this, you will kill the market for years. It’s over. And you’re selling something that you know has no value.

TULD

We are selling to willing buyers at the current fair market price. So that WE MAY SURVIVE!

The villain operates by a Hobbesian, zero-sum code. This code’s highest value is survival. If others must die so that the villain will live, so be it.

The villain looks out for Number One.

Burt Lancaster as Gen. James Mattoon Scott in “Seven Days in May”

A political villain like the Dick Cheney character (Christian Bale) in Vice or Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. James Mattoon Scott (Burt Lancaster) in Seven Days in May may be acting for the survival of his country but only in the sense that he identifies so totally with his country that he might as well be the nation himself.

Beyond the imperative of self-preservation however lies the moral justification that the villain cites to legitimize his lack of empathy for others.

They are less than human.

They are a liability to the greater community.

They are a threat to him personally.

In Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory, WWI French general Mireau (George Macready) congratulates his superior General Broulard (Adolphe Menjou) on the “success” of the execution by firing squad of three innocent soldiers to cover up his own cowardice.

GEN. MIREAU

I’m awfully glad you could be there, George. This sort of thing is always rather grim.

GEN. BROULARD

But this had splendor, don’t you think?

GEN. MIREAU

I have never seen an affair of this sort handled any better. The men died wonderfully. There’s always that chance that one will do something that will leave everyone with a bad taste.

Like the Night King in Game of Thrones or the shark in Jaws, the Villain has one priority only—his own survival and his victory over his enemies. Everything and everyone else is strictly collateral damage.

September 18, 2019

The Villain Never Says He’s Sorry

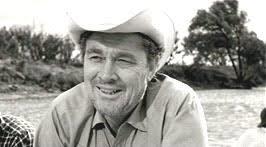

In the classic Western Shane there’s a character named Chris Calloway (played by Ben Johnson, who later won an Oscar for his role as “Sam the Lion” in The Last Picture Show.)

Chris Calloway (Ben Johnson) picking a fight with Shane (Alan Ladd) in “Shane”

Chris Calloway is the original bully in Shane. He’s the first of the Bad Cattlemen to humiliate Shane (Alan Ladd) in the bar room at Grafton’s, calling him “Sody Pop” and slinging a shot of whisky into his face. Chris brawls with Shane and in general shows himself to be a world-class sonofabitch.

But later in the film when Chris learns that his boss, Rufe Ryker, plans to dry-gulch Shane’s friend Joe Starrett and kill him, he has a change of heart. He appears at midnight outside Shane’s door. Shane draws his gun, suspecting treachery. But Chris has come to make amends. “Hold on, Shane. I got something to tell you.”

CHRIS CALLOWAY

Starrett’s up against a stacked deck.

SHANE

Why are you telling me?

CHRIS CALLOWAY

I reckon something’s come over me.

SHANE

I don’t figure.

CHRIS CALLOWAY

I’m quitting Ryker.

Shane realizes that Chris has truly had a change of heart. He lowers his gun. He thanks Chris. The former enemies not only shake hands but seem to actually form a bond of goodwill that might carry forward into the future.

CHRIS CALLOWAY

Be seeing you.

And, with a nod of farewell, Chris rides off into the night.

Ben Johnson in his Oscar-winning role in “The Last Picture Show”

You will never see a villain play a scene like this—that is, one in which he, the villain, faces up to the error of his ways and actually changes.

The villain doesn’t change.

The villain never says he’s sorry.

If he does, like Chris Calloway above, he ceases to be a villain. He becomes the hero of a subplot of the story, in this case the Shane-Calloway Subplot.

Why won’t the villain ever apologize?

Because is his view, he is 100% right. His beliefs are sound. His actions are honorable. To apologize would be to betray his most deeply held convictions.

Remember, the villain does not believe he’s the villain. In his eyes, he’s the Good Guy.

The filmmakers of Vice (writer and director Adam McKay) put the following speech into the mouth of VP Dick Cheney (Christian Bale), who, in the movie’s eyes, is most decidedly the villain.

Christian Bale as VP Dick Cheney in “Vice”

DICK CHENEY

There are monsters in this world. We saw three thousand innocent people burned to death by those monsters. And yet you object when I refuse to kiss those monsters on the cheek and say “Pretty please.” You answer me this: what terrorist attack would you have let go forward so you wouldn’t seem like a mean and nasty fella? I will not apologize for keeping your family safe and I will not apologize for doing what needed to be done so that your loved ones can sleep peaceably at night. It has been my honor to be your servant. You chose me. I did what you asked.

The villain is unrepentant to the end because, in his eyes, he has nothing to repent for.

September 11, 2019

The Mystery Makes the Hero Choose

Let’s stay with Blade Runner in this post, but let’s go back to the 1982 original starring Harrison Ford and Sean Young and directed by Ridley Scott (screenplay by Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples.)

Sean Young as Rachael in the 1982 “Blade Runner”

If indeed, as we’ve been positing in previous posts,

The female carries the mystery

and

The male’s role is to uncover the mystery,

then what happens when he (remember, the “male” can be a female too, as long as she acts in the archetypal rational/assertive/aggressive style of a male) does uncover the mystery?

Answer: he is thrust into a moral crisis.

He is forced to choose.

In the 1982 Blade Runner, the mystery is carried by the character of Rachael (Sean Young.)

The male hero is Blade Runner Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford). His profession is to hunt down and “retire,” i.e. kill, the artificial humans called replicants. In one of the movie’s opening scenes Deckard is sent to the Tyrell Corporation, manufacturer of the new Nexus 6 series of replicants, to test one of these new models on a “Voight Kampf machine.” The machine can tell if a subject is a real human or a replicant.

The founder of the corporation, Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel), has other ideas however. He wants Deckard to use the machine on a real human first.

TYRELL

I want to see a negative before I provide you with a positive.

He summons Rachael (Sean Young), introducing her as his assistant. Deckard runs the test. Sure enough, the machine says Rachael is a replicant.

Though Deckard ends the test without comment, Rachael reads this in his eyes.

Up to that moment, Rachael had no clue that she was artificial. She thought she was a human.

See how she’s “carrying the mystery?”

The movie’s “A” story is already rolling. Deckard has been ordered to track down a team of rebel replicants including Roy (Rutger Hauer) and Pris (Daryl Hannah) who have highjacked an Off-World shuttle and come to Earth with designs of mayhem.

Deckard plunges in to tracking them down.

There’s only one problem.

He has fallen in love with Rachael.

At the same time, Rachael is reeling emotionally from the discovery of her true identity. If she is artificial, what is she? Does she have a soul? Is she human? She has completely convincing memories from childhood. Where did they come from? Implanted by the Tyrell Corporation? Then who or what is she?

Remember too that Deckard’s job is to kill replicants.

Harrison Ford as Rick Deckard in the 1982 “Blade Runner”

Does that mean he must kill Rachael? Yes, says his cop boss Bryant (M. Emmet Walsh).

To make the moral choice even harder for Deckard, in one shoot-out on the street, Rachael saves his life by killing a replicant who’s about to murder Deckard. Now he owes her.

Then there’s the ultimate kicker:

RACHAEL

(to Deckard)

That Voight-Kampf test of yours. Did you ever take it yourself?

By this point in the story, Deckard’s entire world has been turned on its head. He has become 100% emotionally involved in Rachael’s dilemma. He loves her. Her pain has become his pain. But if he doesn’t do what his role as a blade runner commands him to, the consequences for him are as fatal as they are for Rachael.

What is he going to do about this?

In other words,

when the “male” uncovers the mystery carried by the “female,” he is forced to make a moral choice.

A choice that constitutes the theme and soul of the story.

In Casablanca, Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart), encountering the mystery embodied by Ilsa Lund (Ingrid Bergman), must make a choice.

In Chinatown, Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson), coming face to face with the mystery embodied by Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway), must make a choice.

In Blade Runner 2049, K (Ryan Gosling) confronting the mystery carried by Dr. Ana Stelline (Carla Juri), must make a choice.

If you haven’t seen the 1982 Blade Runner, I won’t spoil the ending for you. Suffice it to say, Deckard does what a hero is supposed to do.

Confronting the mystery, he makes a choice.

September 4, 2019

Male and Female in “Blade Runner 2049”

I’m going to generalize wildly in this post so please bear with me. Many exceptions could be cited legitimately to the principle I’m about to put forward (and maybe the principle itself is completely wrong). But it’s thought-provoking and its exploration, I hope, will give us all something to chew on.

Ryan Gosling as “K” in Blade Runner 2049

If, as we have proposed in earlier posts in this series,

The female carries the mystery,

then what is the male’s role?

(Bear in mind that the “male” in our story could be a female, e.g. Diana in Wonder Woman or Sara Paretsky’s tough private eye V.I. Warshawski or any of the powerful female leads in Game of Thrones, etc.)

The male’s role is to uncover the mystery.

The inciting incident of any story (remember, I’m generalizing shamelessly) is the introduction of the mystery.

We, the reader/audience, get hooked by this. As does the “male” lead.

Act Two becomes the male lead’s quest to get to the bottom of the mystery.

In Act Three, he succeeds. But, if the story is a good one, this revelation only leads to a deeper mystery—a mystery that sheds light on some profound aspect of life or love or the human condition.

In Blade Runner 2049, the male principle is embodied by “K” (Ryan Gosling). K is a blade runner—a professional operative whose job is to hunt down and kill the manufactured humans called replicants. K is a replicant himself, and he knows it. He accepts his role and has no aspiration to defy or overthrow it.

The mystery is introduced, i.e. the story’s inciting incident, when K (and his human superior, Lt. Joshi [Robin Wright]) learn that somehow, against all logic and design, a replicant (we don’t know who) has conceived and given birth to a child. That’s an earth-shaking event in the futuristic world of the story because it means that manufactured entities have the potential for becoming human, for actually possessing souls.

That’s also a pretty cool mystery.

K is assigned by Joshi to find and, in the name of world order and stability, to kill this child.

Act Two consists of K’s odyssey attempting to fulfill this assignment.

If our principle holds true, the story’s mystery will be carried by a female.

Sure enough, it is.

After many a twist and turn (during which K comes to believe that he himself is that mysterious child), he encounters Dr. Ana Stelline (Carla Juri), a “memory designer,” who herself, we believe, is a replicant and whose job is to create the artificial memories that will be implanted in other newly-manufactured replicants.

Carla Juri as memory-maker Dr. Ana Stelline in “Blade Runner 2049”

Dr. Stelline is by far the most empathetic (and human) character that K has encountered. She cares. She is kind. K gets a feeling about her.

By Act Three, K has tracked down the fugitive blade runner Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) from the original 1982 movie. Deckard himself is a replicant. From Deckard K learns that Dr. Stelline is indeed the miraculous child he had been hunting.

In other words, K has uncovered the mystery … and this mystery is embodied in a female.

When a story works, as I would say this one does, the superficial mystery—Who is the replicant child?—is reinforced and made profound by the deeper levels of meaning that this mystery implies.

What is “soul?” Where does it come from? Is it “divine?” What does “divine” mean? Does soul possess a life-imperative of its own, that is, will it find its way into any and every life-form?

How should we feel about despised and outcasted groups in society? Dare we dismiss them, as the culture in Blade Runner dismisses replicants, as “soul-less” or subhuman? What if we ourselves are members of such a group?

In Blade Runner 2049, the male has found and identified the female-borne mystery. But this discovery only leads to deeper and more profound levels of mystery.

August 28, 2019

Male and Female in “Lawrence of Arabia”

The movie Lawrence of Arabia, like The Wild Bunch or Seven Samurai or Moby Dick, is a story without any primary female characters. How, then, can it follow the principle we’ve been exploring in the past three posts:

The female carries the mystery.

The answer, I think, is that Lawrence himself (Peter O’Toole) is the female element.

Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif in “Lawrence of Arabia”

Lawrence is the female element and the male element.

The primary issue posed by David Lean’s film Lawrence of Arabia (or at least one of several primary issues) is, to my mind,

How can an individual reconcile his own authentic greatness with the fact that he still remains human, fallible, and mortal?

To me, Lawrence was two people. The male element lay in Lawrence’s insuperable will to pre-eminence. The film emphasizes this young British officer’s superhuman ability to overcome adversity, his capacity to outlast, out-endure, out-survive on their own turf even the most brilliant and redoubtable Arab leaders.

And Lawrence achieved this pre-eminence in the archetypal “male” way—through assertive and aggressive action and initiative. He was the thunder from heaven; he was the rain that made fertile the plain. But Lawrence’s power came from the union of this male aggression with the female element—his genius and his charisma.

This was the mystery. It was the unexplainable, unknowable element that Lawrence brought that no one else—not the greatest and most illustrious commanders and politicians of the British or the Arab camps—could duplicate or explain.

It was Lawrence’s vision and creativity (in other words, the mystery carried by his female half) as much as any “leadership skills” that changed history—Lawrence’s idea to cross the uncrossable Nefud desert, to attack the Turkish stronghold at Aqaba from the landward side, and much, much more.

SHERIF ALI (OMAR SHARIF)

Truly for some men nothing is written unless they write it themselves.

The turning point in Lawrence of Arabia comes when Lawrence is captured by the Turks and tortured. Before this, his self-conception had been entirely “male,” that is cerebral, mental, “of reason.” But in that long night of beatings, Lawrence’s flesh gave way and his mind followed.

How can an individual reconcile his own authentic greatness with the fact that he still remains human, fallible, and mortal?

Another way of phrasing this might be

What becomes of the female half of us, which carries the mystery/power/creativity, when the male principle has lost faith in its own capacity?

T.E. Lawrence was as much a mystery to himself as he was to others. His saga, on the deepest level, was about his attempt to understand himself, that is, to reconcile the fact of his greatness with the simultaneous reality of his human frailty and mortality.

In a detective story like Chinatown or The Maltese Falcon, the male-female dynamic plays out between the Private Eye and the Femme Fatale. The male is attempting to solve the mystery presented by and carried by the female.

This was Lawrence’s internal story too. His quest was to find, to know, and to understand the unfathomable source of his own genius. He was simultaneously the detective and the woman of mystery.

The second half of Lawrence of Arabia is about Lawrence reconstituting that force and that charisma—but now out of despair instead of hope … and out of the foreknowledge of ultimate defeat even in the actuality of victory.

To me that is what made the historical Lawrence truly great. And also what made his story a tragedy.

The movie of Lawrence of Arabia begins, in a flash-forward, with Lawrence’s essential suicide in a motorcycle crash. This is really the movie’s end.

The movie answers its own question,

How can an individual reconcile his own authentic greatness with the fact that he remains ultimately human, fallible, and mortal?

And the answer is, “You can’t.” Or at least Lawrence, the historical Lawrence, couldn’t.

What insight do I take from this? One, at least, is the realization that we as storytellers don’t need a literally female character to remain true to the principle that

the female carries the mystery.

The male can carry this too.

We all, as has been said many times, contain both principles—male and female. Part of our internal saga must thus be the attempt to identify, to understand, and to learn to work with these opposing poles that constitute the source of our genius and our capacity for creativity.

August 21, 2019

What is “Female?”

In the past two posts we’ve been exploring the story idea that “the female carries the mystery.”

But what exactly does “female” mean?

Kathleen Turner and William Hurt clash in Lawrence Kasdan’s “Body Heat”

Our reader Amber in an August 7 comment said

Then I understood that it wasn’t female as a gender, but female as the concept. The feminine pull vs the masculine push. In this instance, the female “hide” vs the masculine “seek”.

Andrea Reiman added something equally interesting.

The feminine is chaos, the masculine is order. Mountains are masculine, water is feminine, etc. But [“the] female carries the mystery” is a more nuanced understanding of chaos. Well, she does conceive, carry, and give birth, but it is a complete mystery how the conception took place, what is developing in utero, and what specific impact that offspring will have, right?

I confess I’m treading tentatively into this concept myself. Here’s another take from The Kybalion (1912, the Yogi Publication Society) expounding on one of the seven principles of Hermetic philosophy—the Principle of Gender:

The office is Gender is solely that of creating, producing, generating, etc. and its manifestations are visible on every plane of phenomena … the part of the Masculine Principle seems to be that of directing a certain inherent energy toward the Feminine Principle, and thus starting into activity the creative processes. But the Feminine principle is the one always doing the active creative work—and this is so on all planes. And yet each principle is incapable of operative energy without the assistance of the other.

In story terms, whatever element or character we might call “female” is the one that contains the “answer” to the question posed by the story itself—and that answer, at its most profound, is always a mystery.

I wrote, two posts ago, that I thought the feminine in Moby Dick (a book without literally female characters) was the ocean itself, the unfathomable depths of the sea. And that the female in Seven Samurai (a movie without a primary feminine character) was the flooded rice fields that the villagers were planting in the final scene.

Both these “female” elements are primal, elemental, ultimately unknowable—and of course cosmically “creative.” Both are the sources of life. And in both cases, how the feminine produces that life (as Andrea Reiman says above) is an absolute mystery.

The male element and the female element (with Gregory Peck as Captain Ahab) in “Moby Dick.”

Neither story universe could exist without these female elements. They are the ground and foundation of the worlds of both sagas. All the “male” action in each drama—that taken by the whalers in Moby Dick and the bandits, the villagers, and the samurai in Seven Samurai—is about attempts to penetrate, conquer, understand, and achieve dominion over the “female” element, which is ultimately unconquerable and unknowable.

In both stories, the male stands in awe of the female (though he may never overtly articulate this), while striving simultaneously to overpower it and surrender to it. This struggle/attempt at union is what produces the drama. It’s what makes the story.

The seminal male-female union/clash in contemporary books and films seems to be the Detective (or the male lover) and the Femme Fatale (or damsel in distress.) Think Chinatown or Body Heat or Farewell, My Lovely. In such stories, as with Moby Dick or Seven Samurai, the male principle becomes bewitched by or drawn by powerful passions into a literal mystery (a crime, a backstory, a traumatic past) whose unknown element is held by, defended by, and often manipulated by the female.

The story itself is the record of the attempt(s) by the male principle to “get to the bottom” of that mystery held and protected by the female.

Deep stuff, ain’t it? We’ll keep exploring next week.