Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 34

July 29, 2020

The Villain is the Hero’s Nemesis

The obstacles that the hero confronts In Act Two can’t arise willy-nilly from everywhere and nowhere. They must originate from a single source—the villain.

Fernando Rey as Alain Charnier in William Friedkin’s “The French Connection”

Fernando Rey as Alain Charnier in William Friedkin’s “The French Connection”One of the great antagonists/nemeses in movie history is Alain Charnier (Fernando Rey) in William Friedkin’s 1971 classic, The French Connection.

Throughout Act Two, this urbane Frenchman and big-time drug smuggler torments the movie’s hero, NYPD detective Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman) relentlessly and exquisitely, always keeping one jump ahead and always making Popeye look like a chump.

Like the zombies in The Dead Don’t Die or the Tripods in War of the Worlds, the villain is the source of all the hero’s troubles.

Even when the hero is dueling internal demons of his or her own (like Popeye’s rage and burning passion to make this bust), or struggling with hostile allies (the Feds attached to his case) or other “friendly fire” antagonists (his boss at the precinct [played, by the way, by the real “Popeye Doyle,” Detective Eddie Egan], the actions of the villain are what trigger and reinforce these supplementary nemeses.

In a way, this idea is a corollary to, or restatement of, Steven Cannell’s famous axiom:

Act Two belongs to the Villain

In Act One, we in the audience may be introduced to the villain (think of Charnier in France preparing his heroin-smuggling operation or the Tripods being activated in their subterranean lairs by the super storm from space). We may experience anticipatory chills at the Evil One’s apparition. But it’s not till Act Two that the hero truly becomes engaged with the Bad Guy.

That’s when you and I as writers have to pour oil on the fire.

I know, when I’m stuck in my Second Act, I remind myself, “Go back to the villain. Make him or her smarter, make him/her more formidable, more ruthless, more dangerous.”

July 22, 2020

The King Archetype

The following is a true story, paraphrased from Plutarch’s Life of Alexander.

Colin Farrell in the title role of Oliver Stone’s “Alexander”

Colin Farrell in the title role of Oliver Stone’s “Alexander”Once Alexander the Great was leading his army across a waterless desert. The column was strung out for miles, with men and horses suffering terribly from thirst.

Suddenly a detachment of scouts came galloping back to the king. They had found a small spring and had managed to fill a helmet with water. They rushed to Alexander and presented this to him. The army held in place, watching. Every man’s eye was fixed upon the king.

Alexander thanked his scouts for bringing him this gift. Then, without touching a drop, he lifted the helmet and poured the precious liquid into the sand.

At once a great cheer ascended from the army, rolling from one end of the column to the other. A soldier was heard to say, “With a king like this to lead us, no force on earth can stand against us.”

I’ve been re-reading one of my favorite books, King Warrior Magician Lover, by the Jungian psychologists Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette. The title refers to (some of) the archetypes of the Collective Unconscious.

When you and I struggle to control our work habits, i.e. to confront and overcome our Resistance, sometimes the trouble lies in which archetype we’ve allowed ourselves to settle into.

For years I lived in the Lost Boy archetype. Needless to say, I didn’t get a damn thing done.

The archetype we’re aiming for, I think (at least short of the Sage or the Magician) is the King.

When the king is strong, the kingdom prospers. When the king rules with wisdom and justice, the land flourishes and the people are happy.

Can you and I lead like Alexander in the story above?

Can we embrace adversity and be willing to make the sacrifices necessary for our project to reach fruition?

Can we be the king (or queen) of our own aspirations?

July 15, 2020

Get to “I Love You,” Cosmic Version

We’ve been saying over the past couple of weeks that the dramatic arcs of many, many novels and movies can be seen as simply

Get to “I love you.”

Start with two characters who are as far apart as they can be (or are indifferent or utterly resistant to one another), then bring them together somehow over the course of the story so that by the final moment they connect truly on the deepest, most intimate level.

The next question is, “Why does this work?”

Why does it always work?

Here’s my answer on the cosmic level:

I think “Get to ‘I love you’” is the prime spiritual imperative of human life itself.

One of the great “Get to ‘I love you’s’” in recent films is the final moment in Logan. Do you know the movie? It’s the concluding episode in the X-Men Wolverine saga, starring Hugh Jackman as the steel-clawed mutant who is too isolated, too traumatized, too dark to care or to love.

Dafne Keen and Hugh Jackman as “Laura” and “Logan”

Dafne Keen and Hugh Jackman as “Laura” and “Logan”Now in this final instalment, in his most-human-like form as “Logan,” he shares a geographic and emotional odyssey with a young mutant girl named Laura (Dafne Keen), who also possesses the Wolverine claws and the Wolverine fury, having been laboratory-conceived and laboratory-bred from Logan’s own DNA.

But Laura loves him. He’s a father figure to her. She needs him. She wants to help him. She becomes attached to him.

Logan/Wolverine resists young Laura throughout the story until finally finally finally, after saving her from the Bad Guys … and having allowed her at last into his cold, bitter heart, with his terminal breath he declares

LOGAN

So this is what it feels like.

And he dies.

He dies happy, or at least at peace.

I think that’s the journey of every human. It’s Odysseus’ journey, it’s Hamlet’s, it’s Henry Miller’s. It’s yours and mine.

If you follow this blog, you know that I believe life happens on two levels—the material plane and the plane of the soul.

On the material level, we show up in physical form as isolated individuals. I can hurt you and it won’t hurt me. I can ignore you and it won’t hurt me. I can kill you and it won’t hurt me.

But on the cosmic plane, the laws are different.

We’re all one on that plane.

All souls are interconnected and interdependent.

If I hurt you, it hurts me, etc.

I don’t know why all of us or any of us were put here or appeared here on this dark and brutal plane, unless it was … maybe … to learn that lesson. To make that breakthrough to love.

To live by the laws of the higher plane here on the lower.

That’s what stories are about, if you ask me. That’s their purpose. That’s why we need them. They’re here to show us, to inspire us to get to “I love you.”

Interesting too, isn’t it, how many of the most moving stories end with the principal character, the hero, sacrificing his or her life … all she has, all she will ever have … for love, for another human being. And that that sacrifice is, in the story, the ultimate act of self-realization and fulfilment.

LOGAN

So this is what it feels like.

He got to “I love you.”

July 8, 2020

Get to “I Love You,” Continued

True, there are wonderful stories that end with one character declaring (on the nose, as they say in Hollywood), “I love you.”

But it seems to work much better when the declaration is either silent, or expressed by an image or a gesture, or articulated in a phrase that’s as far away from “I love you” as possible.

Ben Johnson, Warren Oates, William Holden and Ernest Borgnine after saying “I love you” in Sam Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch”

Ben Johnson, Warren Oates, William Holden and Ernest Borgnine after saying “I love you” in Sam Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch”Why?

It’s more fun.

The reader or audience gets it. They know Character A is declaring his love for Character B. So …

“Shut up and deal”

or

“Best job I ever had”

or

“Ah, f*@k it, Dude. Let’s go bowling”

deliver the goods and let the audience or reader fill in the emotional blank themselves.

In other words, the farther away we can make our overt final line from “I love you” (while still clearly meaning exactly that), the better.

“Text” is the line as written or spoken.

“Subtext” is the true meaning underlying the spoken or written line.

Subtext is always better than text because it lets the reader/audience participate.

The scene leading to the climax of The Wild Bunch is one of the great examples of subtext-beats-the-hell-out-of-text when saying “I love you.”

The Wild Bunch is the outlaw band based very loosely on the true historical gang of the same name, also known as the Hole in the Wall Gang or Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. In Sam Peckinpah’s 1969 film of that name, the Wild Bunch in this final scene consists of Pike (William Holden), Dutch (Ernest Borgnine), Lyle and Tector Gortch (Warren Oates and Ben Johnson) and Angel (Jaime Sanchez.)

Setting; Mexico in the Pancho Villa era. The evil generalissimo Mapache has captured and tortured Angel, while the Bunch has been unable to take action because of the overwhelming number of Mapache’s troops. In the prelude to the final bloodbath, the Bunch wakes up after an all-night, self-loathing debauch in the dusty Mexican village where Mapache’s troops hold the captive Angel.

Pike is the leader of the Bunch. He stands and pays (very generously) the woman he has spent the night with.

He straps on his gunbelt.

Without a word Pike appears in the doorway of the room across the hall, where the Gortch brothers are wrapping up their own sordid night.

Pike’s eyes meet Lyle’s.

Lyle squints back.

LYLE GORTCH (WARREN OATES)

Why not?

Lyle and Tector stand and strap on their guns. They step outside. Dutch sits in the blistering sun with his back against the adobe wall of the house. He is whittling a stick.

Dutch looks up.

His eyes meet the eyes of his compadres.

With a laugh, Dutch plunges the sharpened stick into the dust. He stands.

That’s “I love you,” as leanly and as eloquently as it can possibly be said.

July 1, 2020

Get to “I Love You”

“Shut up and deal.”

“Would it kill you one time to put on a dress?”

“Walter, you’re all washed up.”

I’m sure we can all think of a million more, but these are famous last lines, delivered respectively by Shirley MacLaine, Art Carney, and Edward G. Robinson from, in order, The Apartment, The Late Show, and Double Indemnity.

What do they have in common?

They all mean, “I love you.”

Shirley MacLaine declares her love for Jack Lemmon in Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment”

Shirley MacLaine declares her love for Jack Lemmon in Billy Wilder’s “The Apartment”[P.S. for writers’ credits, let’s give it up for Billy Wilder & I.A.L. Diamond, Robert Benton, and Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler.]

It doesn’t work for all novels and movies but here’s an axiom I’ve found tremendously helpful as I work on a new story:

Get to “I love you.”

Moby Dick can be viewed as a love story between Ishmael and Queequeg. When the Pequod goes to the bottom with all hands and Ishmael is saved—by Queequeg’s watertight (empty) coffin bobbing to the surface—that’s “I love you.”

When Walter White (Bryan Cranston) bites the dust in the final episode of Breaking Bad, thus saving Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul), that’s “I love you.”

Story after wonderful story starts with two characters who are miles apart in every way … and ends with the twain coming together as if it were the most natural and inevitable thing in the world.

Can you identify the sources of these “I love yous”?

“I told you I don’t want you riding with me no more.”

“Want something? Pie?”

“Why not?”

Hint: these lines are delivered by, in order, Ryan O’Neal, Robert Duvall, and Warren Oates.

(I would say “Answers next week,” but for sure the Comments section will answer them all within ten minutes of this post going up. I’m talking about YOU, Joe Jansen.)

June 24, 2020

Does Nonfiction Need an Inciting Incident?

Have you seen Elizabeth Gilbert’s 19-million-view TED talk, “Your Elusive Creative Genius?”

Elizabeth Gilbert, from her 2009 TED talk

Elizabeth Gilbert, from her 2009 TED talkI am a writer. Writing books is my profession but it’s more than that, of course. It is also my great lifelong love and fascination. And I don’t expect that that’s ever going to change. But, that said, something kind of peculiar has happened recently in my life and in my career, which has caused me to have to recalibrate my whole relationship with this work. And the peculiar thing is that I recently wrote this book, this memoir called “Eat, Pray, Love” which, decidedly unlike any of my previous books, went out in the world for some reason, and became this big, mega-sensation, international bestseller thing. The result of which is that everywhere I go now, people treat me like I’m doomed. Seriously — doomed, doomed! Like, they come up to me now, all worried, and they say, “Aren’t you afraid you’re never going to be able to top that? Aren’t you afraid you’re going to keep writing for your whole life and you’re never again going to create a book that anybody in the world cares about at all, ever again?”

See the inciting incident? It’s the moment when “people” (and by extension Elizabeth herself) start to fear for the writer’s future, as she endeavors to follow up her huge bestselling hit.

In this moment Ms. Gilbert, like a protagonist in a novel, acquires her intention—to find some mindset that either obviates or overcomes this terror. (Full disclosure: she does.)

You and I as writers of nonfiction need an inciting incident just as much as fiction writers do.

June 17, 2020

A Body of Work

I believe that Bruce Springsteen’s musical creations existed before he ever picked up a guitar or sat down at a piano.

As did Bob Dylan’s and Joni Mitchell’s and George Gershwin’s.

George Gershwin in the year of “Rhapsody in Blue”

George Gershwin in the year of “Rhapsody in Blue”They existed, I believe, on another plane of reality. Maybe not note for note, maybe not line for line. But in some form that was recognizably Dylanesque or Mitchell-like or Gershwin-close.

The individual artist, opening him- or herself to the dimension of potentiality, called these works down.

Bruce and Joni and George tuned themselves to the Cosmic Radio Station and heard (as no one but each of them could hear) the music that was for them alone to bring forth.

Do you believe me? Then believe this:

You

too have a body of work.

It exists inside you … and has existed from the moment you were born, and possibly even before that.

Your body of work, like Springsteen’s or Joni Mitchell’s or George Gershwin’s, is unique to you. No other indiviudal, living or dead, can produce or could have produced it.

It is yours alone, and it is real.

June 10, 2020

Which “I” am I?

When we call ourselves “I,” which “I” do

we mean?

There’s the first”I”—our ego, our conscious self, our reasoning intellect. That’s the “I” that writes a grocery list, identifies itself to the census, raises a family, subscribes to the daily paper.

Nicolas Cage as Charlie Kaufman in “Adaptation” confronting the Fifth “I”

Nicolas Cage as Charlie Kaufman in “Adaptation” confronting the Fifth “I”But if we go to yoga class or sit down to meditate, we come immediately upon a second “I.” This “I” watches us as we enter Downward Dog or endeavor to calm the mindless chatter inside our skulls. This “I” is a witness. It’s somewhere “behind” or “above” the first “I.”

There’s a third “I” that can witness us witnesses ourselves.

Not to mention a fourth “I” that stands in for us in our dreams.

Which one are we?

There’s a fifth “I” as well. That’s the one that writes our books, paints our paintings, starts our start-ups.

The fifth “I” operates independently of the first four.

That’s the “I” I’m interested in.

People ask me sometimes, “Don’t you get lonely, just being in a room by yourself all day?”

No.

I’m not lonely because I’m with this other “me,” who is me and not-me at the same time and whom I have spent my entire life trying to find, to prove myself worthy of, and to labor in collaboration with.

June 3, 2020

“DVEKUT BA MESIMA”

The following passage is from Lieutenant Giora Romm, the first fighter-pilot ace [shooting down five enemy planes] of the Israel Air Force:

When I was fifteen [in 1960], I applied for and was accepted into a new military boarding school associated with the Reali School in Haifa. I don’t believe there is an institution in Israel today that can measure up to the standards of that school. Why did I want to go there? I wanted to test myself.

At that time in Israel the ideal to which an individual aspired was inclusion as part of a “serving elite.” The best of the best were not motivated by money or fame. Their aim was to serve the nation, to sacrifice their lives if necessary. At the military boarding school, it was assumed that every graduate would volunteer for a fighting unit, the more elite the better. We studied, we played sports, we trekked. We hiked all over Israel. We were unbelievably strong physically. But what was even more powerful were the precepts the school hammered into our skulls.

First: complete the mission.

The phrase in Hebrew is Dvekut baMesima.

Mesima is “mission,” dvekut means “glued to.” The mission is everything. At all costs, it must be carried through to completion.

I remember running up the Snake Trail at Masada one summer at 110 degrees Fahrenheit with two of my classmates. Each of us would sooner have died than be first to call, “Hey, slow down!”

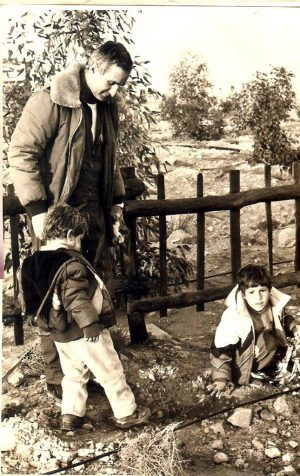

Giora Romm in 1973 with his sons

Giora Romm in 1973 with his sonsThe Lion’s Gate, pp. 14-15

Readers sometimes take me to task for making so many

analogies to battles and actions of war.

But

you and I are warriors.

We

are on a mission, no less than fighter pilots and tank commanders, and the

stakes for us, as for them, are life and death.

“The mission is everything. At all costs it must be carried through to completion.”

May 27, 2020

Keep Working

The great thing about working as a writer (as opposed to being, say, an actor) is you only need a pencil and a piece of paper to work.

Nobody can stop you from writing a novel.

It doesn’t matter where you’re working. You’re a writer.

No one can stop you from banging out a screenplay.

Maybe you’re not being paid, maybe nobody knows who you are, maybe no one will ever read, let alone publish or produce your book or movie.

But you can KEEP WORKING entirely on your own.

I have a closet in my office. In it are thirty-seven screenplays. Seven of them actually brought in money, at least in the form of an option if not an actual sale. That means thirty (six months of work apiece) were technically for naught.

But those scripts let me KEEP WORKING.

With each one, I learned something. On some, I learned a lot.

If you have to take a gig driving for Uber or waiting tables at Hooters, it’s okay.

Keep writing.

Nobody can stop you from getting up at five in the morning and putting in three hours pounding the keys.

Or two hours.

Or one.

When someone asks you what you do for a living, answer, “I’m a writer.”

You are.

Keep writing.