Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 33

August 31, 2020

Episode Five: A Society of Virtue

Lycurgus was the founder of Sparta. The first thing he did was outlaw money. He wanted his people to pursue virtue instead.

The equivalent of a Spartan dime was a two-pound lump of iron, dipped in vinegar so it would be useless for any other purpose.

In today’s video, we’ll examine the warrior virtues that the ancients aspired to … and begin to ask how these ideals can be applied today (and should be applied) to other kinder, gentler pursuits.

The post Episode Five: A Society of Virtue first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

Episode 5: A Society of Virtue

Lycurgus was the founder of Sparta. The first thing he did was outlaw money. He wanted his people to pursue virtue instead.

The equivalent of a Spartan dime was a two-pound lump of iron, dipped in vinegar so it would be useless for any other purpose.

In today’s video, we’ll examine the warrior virtues that the ancients aspired to … and begin to ask how these ideals can be applied today (and should be applied) to other kinder, gentler pursuits.

The post Episode 5: A Society of Virtue first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

August 27, 2020

Episode Four: “Add a Step to It”

Spartan quips and Spartan swords were notoriously short.

The story goes that a young warrior remarked on this stubbiness the first time his mother handed him this weapon.

Her reply?

“Add a step to it.”

Meaning, Get that much closer to the enemy.

In today’s video, we explore the clipped, laconic speech of the ancient Spartans and tell the tale of their famous one-word response to a king who threatened to invade their country.

The post Episode Four: “Add a Step to It” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

August 26, 2020

Get to True Identity

We’ve talked in recent weeks about the story-defining concept of

Get to “I love you.”

For me, as I’m working on a new story, this way of thinking is tremendously helpful. It doesn’t work for every book or screenplay but it sure works for a lot of ‘em.

Start with two characters who are as far apart emotionally, materially, politically, and spiritually as possible. They don’t have to be actual lovers, nor does “I love you” have to imply anything physical or romantic. The pair can be an adult and a child (Paper Moon and True Grit), a human and a non-human, a mouse and a mutant. “I love you” can happen within a single character (Far from Heaven), who at story’s end comes to accept and embrace not a separate character but her own self.

Here’s another paradigm I find extremely helpful:

Get to true identity.

In the climax of Huckleberry Finn, when Huck tears up the letter he had forced himself to write turning in his friend Jim, he has reached his true identity.

When Bogey puts Ingrid on the plane to Lisbon, he has reached his true identity.

When Thelma and Louise go soaring into thin air in their ’66 T-bird, they have reached their true identity.

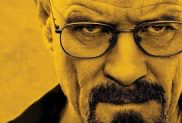

Walter White (Bryan Cranston) gets to his true identity as “Heisenberg” in Vince Gilligan’s BREAKING BAD

Walter White (Bryan Cranston) gets to his true identity as “Heisenberg” in Vince Gilligan’s BREAKING BADPick any one of a thousand books or movies (dramas, tragedies, comedies … the principle applies across the board) and you’ll see more often than not this paradigmatic progression:

Act One: Hero starts with a warped and deformed self-conception (Huck, Thelma, Bogey).

Act Two: Hero is compelled by events and her own decisions to embrace a new and initially terrifying (to her) view of herself.

Act Three: In climax, hero embraces this new identity-what we as viewers and readers can see clearly as her true identity-whole-heartedly and in a manner that permits of no going back.

Even mild-mannered Walter White (Bryan Cranston) in Breaking Bad, by the end of series when he has become the arch-villain “Heisenberg,” is true to this principle. That’s why for me the whole burn-down-the-world ending worked. Even within his unrepentant villainy, Walter/Heisenberg manages to sacrifice himself to save his friend Jesse (Aaron Paul).

P.S. On another subject, if you missed the announcement last week of our new video series, The Warrior Archetype, you can sign up (below) to subscribe.

The post Get to True Identity first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

August 24, 2020

Episode Three: Spartan Women, Part Two

Why did king Leonidas pick the specific 300 warriors that he did to fight the Persians (and to face certain death) at Thermopylae?

To this day, no one knows.

In Gates of Fire, I imagined an answer. Leonidas chose his Three Hundred—including himself, for he knew he too would die in the coming battle—not for their own courage but for the courage of their women.

In today’s video, we’ll investigate further the mindset of these wives and mothers, sisters and daughters of the ancient world’s premier warrior culture.

The post Episode Three: Spartan Women, Part Two first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

August 20, 2020

Episode Two: “With This Or On It”

It’s only fitting to begin our exploration of the Warrior Archetype with ancient Sparta. But let’s not start with the men. Let’s start with the women. Spartan women were famous as the most beautiful and the free-est in the ancient world. But they were also the toughest-minded and the fiercest enforcers of the warrior ethos to which their husbands, sons, and fathers aspired. Let’s begin this series with them.

The post Episode Two: "With This Or On It" first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

August 19, 2020

A COVID-spawned enterprise

When the coronavirus first hit, I thought to myself, “How can I help? People are facing tremendous new psychological and emotional challenges. What can I share? How can I contribute?”

I started doing a no-frills video series on Instagram … just two-minute pieces with me on-camera … in which I’d recommend books that I thought might fortify all of us in this new upside-down world. Inevitably a bunch of these titles came from the ancient world—Xenophon, Herodotus, Arrian, Thucydides, etc.

Short version:

I’ve decided to expand this series.

This intro video describes what I’m trying to do.

I’m calling the series The Warrior Archetype. The episodes will be five or six minutes instead of two. I’m planning on fifty episodes or more. Two a week. Monday and Thursday. All videos with transcripts.

I’m going to start with the ancient Spartans and Athenians and follow the thread up through the Macedonians under Alexander the Great, the Romans … and on into the Bhagavad-Gita and the inner war that you and I fight every day, not just against the forces of self-sabotage inside our own heads but against the individual and collective dark energy that seems to be inundating the nation and the planet more and more every day.

There’s a SUBSCRIBE box at the bottom of the page. Sign up and you’ll get the (free) episodes in your inbox, just like “Writing Wednesdays.” I would not presume to automatically switch any current “WW” subscriber over. If you don’t opt-in, you won’t get the new series.

P.S. Don’t worry, “Writing Wednesdays” is not going anywhere. “WW” will continue to be delivered every Wednesday. It ain’t going away!

August 17, 2020

Episode One: Introducing The Warrior Archetype

Today begins a new video series. I’ll be spending the next several months talking about what I call The Warrior Archetype. This series will look at the idea of what a warrior is in ancient times and modern times; the internal battle and the external battle; the warrior in each of us. Hope you’ll join me. Looking forward to comments and new conversations.

August 12, 2020

Mystery = Heart of Darkness

Remember the principle we were examining a few months ago?

The female carries the mystery.

Let’s explore this in the movie Apocalypse Now.

The central image/passage of the 1979 Francis Ford Coppola film is a journey upriver. Hard to think of a more “female” construct, particularly when the voyage is cast from the story’s inception as an odyssey into the dangerous and the unknown.

When we recall, in addition, that Apocalypse Now is derived from Joseph Conrad’s novel, Heart of Darkness, we are more certain than ever that the primal image and narrative architecture is female.

Martin Sheen as Capt. Willard in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now

Martin Sheen as Capt. Willard in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse NowOur male lead is army Captain Benjamin Willard (Martin Sheen), who is tasked by his superiors to venture upriver, locate a certain Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando) and “terminate his command,” i.e. kill him. Why? Because although Kurtz has been astonishingly successful in carrying out his mission in military terms, he has apparently “gone native.”

Wildly native.

Kurtz has gotten out of hand, say his downriver superiors. He is operating beyond all command and control. His methods, the army brass declare, are “unsound.”

“Terminate,” the officers instruct Willard, “with extreme prejudice.”

But for our young captain, as he commences his journey upriver and begins to study Kurtz’s service records and learn his history—top of his class at West Point, multiple awards for valor, rapid promotion after rapid promotion—the focus of the enterprise alters for him.

It becomes more about fathoming the Mystery.

Who is Kurtz?

Is he a madman or a genius?

What has he discovered, of life or of himself, deep in the jungle?

We, watching the movie, are of course asking the same questions.

What exactly is the mystery in the deepest sense—the “female” that the film is seeking to explore and to understand?

The mystery is Vietnam.

Specifically, the mystery is Vietnam as a theater of war in which we Americans—a self-described unbeatable military, cultural, and economic power—find ourselves up against a foe whom our methods can’t seem to defeat.

The mystery is the enemy.

Who are these little guys in black pajamas? What do they know that we don’t? And why are they kicking our ass?

The mystery is the jungle.

The mystery is the hidden, the occult, the unknown. It is that which eludes our helicopters and spy planes and satellites, that which cannot be bombed or Agent Oranged into submission.

The mystery is our own inner darkness.

Why are we in Vietnam in the first place? What is our objective? What are we trying to accomplish? For whom? And why?

When you and I as writers seek to apply a principle like “the female carries the mystery” in studying and evaluating a specific work like Apocalypse Now, what exactly are we trying to accomplish?

First, we’re testing the principle to see if it holds water. Does it apply? Is it a key or road map to the movie’s inner meaning? Can it help us gain insight? Most importantly, can we then use this principle in seeking to understand our own stories, particularly whatever tale we happen to be working on now?

Can we ask ourselves, of our current story, “Is there a ‘female?’ Who is it? What is it? Is it ‘carrying a mystery?’ Is there a ‘male’ character seeking to unravel or reveal this mystery? What, in our story, is the mystery?”

August 5, 2020

Get to “I Love You” with One Character

Far from Heaven (2002) is not an all-time great movie, but I confess I love it. Almost entirely for the ending, which to me is devastating.

Julianne Moore as Cathy Whitaker in Todd Haynes’ “Far from Heaven’

Julianne Moore as Cathy Whitaker in Todd Haynes’ “Far from Heaven’I won’t spoil it for you except to say that our heroine (Julianne Moore as Cathy Whitaker, a 1950s suburban housewife) rides off into a very dark sunset.

And yet …

And yet it’s a happy ending.

I’ve wondered for a long time why this seemingly despairing finish is actually so uplifting. The answer struck me just now, writing this short series of “Get to ‘I Love You’” posts.

The protagonist in Far from Heaven does not get to “I love you” with any other character in the story.

But she does get there with herself.

There’s no scene that plays this transformation, at least not overtly. Cathy doesn’t have a moment when she looks into the mirror and her eyes meet the eyes of her reflection, or a scene where she literally verbalizes something to this effect.

But the movie does execute a great non-on-the-nose version of this. (Again, I won’t spoil it for you.)

Get to “I love you” with one character is, in the deepest sense, what we’re all seeking in life, isn’t it?

Self-acceptance.

Self-affirmation.

Self-belief.

I had a letter just today from a young artist who was absolutely wallowing in self-loathing. Paralyzed to do her work. Hating herself. Seeing no way out.

Resistance is a mofo, ain’t it?

How much of our own self-disconnection, self-castigation, self-annihilation is straight-up Resistance?

Face who we are.

Accept it.

Act upon it.

Get to “I love you” with our own selves.

P.S. Far from Heaven has an interesting origin story. The film was written and directed by Todd Haynes (Carol, I’m Not There) who apparently has always been a fan of movies by the mid-century director Douglas Sirk (All that Heaven Allows, Imitation of Life), whose films were stylish, languorous, glamorous 1950s melodramas.

Todd Haynes got it into his head that he wanted to do a Douglas Sirk-like movie … today.

Far from Heaven was that.

What’s fascinating to me was that Mr. Haynes originally intended to stage scenes shot-for-shot, camera-move-for-camera-move the way Douglas Sirk did. In other words, to imitate Sirk’s style exactly. But he found, when he tried this, that audience attention spans (not to mention his own) had shortened so dramatically since the 50s that he absolutely couldn’t do it. He had to compress and speed up everything.

Anyway, that’s Far from Heaven. You may hate it, but I promise you’ll get the message in the climax.

The movie gets to “I love you” with one character.