Simon Johnson's Blog, page 31

November 7, 2012

And a Few Thoughts About the Election

By James Kwak

Just about everything has been said already, but:

There was a lot of talk, and rightly so, about Barack Obama’s overwhelming victory among Latinos. There was little talk about Obama’s even more overwhelming victory among Asian-Americans, who are the fastest-growing demographic group in the country. For decades people have said that Asian-Americans are a natural Republican constituency. But they said that about Latinos, too.

In the broad sweep of history, it will be hard to see 2012 as a turning point, given its endorsement of the status quo. With one exception: it was the night that gay rights broke through. Besides Tammy Baldwin, besides victory in all four states (Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Washington), there was the roar of applause when Barack Obama said “gay or straight,” and even the Republican commentators talking about how their party had to get on the right side of the issue.

Last night, when the outcome was clear, David Brooks said that if Obama reached across the aisle, he could gain the support of 15 to 20 Republican senators—proving that he can smoothly transition from being unable to interpret polls to being unable to interpret election results.

Amid all the gratifying things about election night (with Elizabeth Warren at the top of the list), here are few more: “Joe” the “Plumber” losing, the replacement of Joe Lieberman, Karl Rove and Donald Trump displaying their craziness.

And, of course, the final word must go to xkcd. Go math!

A Few Thoughts on Nate Silver

By James Kwak

Many people have spilled far more words on this topic than I can read, but I wanted to point out a few things that seem clear to me:

As Daniel Engber pointed out, the fact that Obama won (and that Silver called all fifty states correctly) doesn’t prove that Silver is a genius any more than Obama’s losing would have proven that he was a fraud.

In fact, Silver appears to have gotten a couple of Senate races wrong, but that still doesn’t prove anything, since his model spits out probabilities, not certainties.

To my mind, the crux of the debate was between: (a) people who believe that it is meaningful to make probabilistic statements about the future based on existing data (both current polls and parameters estimated from historical data); and (b) people who believe that there is something ineffable about politics that escapes analysis and that therefore there is something fundamentally wrong, or misleading, or fraudulent about the statistical approach. Silver, through no fault of his own, because associated with (a). To my mind, (a) is right and (b) is wrong because of logic and math, so the idea that one election could have settled the question was crazy to begin with.

Within camp (b), there are certainly valid methodological debates, and it’s by no means clear that Silver is the state of the art. Whether, in the last days of an election, he is any better than simple averages is an open question. The value Silver adds or doesn’t add can’t be judged by the final forecast, because one point of his model is to incorporate factors that are not incorporated in current polls (e.g., economic conditions). (Another aspect of the model is to not overreact to short-term trends—but that aspect also largely vanishes by the night before.) So the superiority of the model, if it is superior, would appear months before the election, not the night before. But that is even harder to verify by ultimate results. Ideally you would have many elections and for each one you would have a Silver forecast six months before and a simple poll average six months before and you would see which had a higher batting average. I would bet on Silver, but we’ll never have enough data to resolve that question.

If the outcome makes people take statistics more seriously and pundits less seriously, that’s a good thing, but it’s not why you should take statistics more seriously.

November 4, 2012

New Threat to the Financial System: Gravity

By James Kwak

Last week reminded everyone that the heart of our financial system remains in Lower Manhattan, just a few feet above sea level. Amid all the tragedy and hardship, Knight Capital—the firm that earlier almost collapsed because of a software glitch—had to shut down its trading operations on Wednesday when its backup generators ran out of fuel.

Why? The answer is so ridiculous you wouldn’t believe me if I summarized it, so here is the story, according to the Wall Street Journal:

The company calculated that its three fuel tanks held a total of 1,200 gallons, or enough to power the generators “past 2 p.m.” [CEO Thomas Joyce] wrote. But the generators unexpectedly shut down at about 11:45 a.m. The problem: Fuel still in the tanks was useless. “Turns out the intake pipes, which [get] the fuel from tanks to generators, are higher than the bottom of the fuel tanks,” Mr. Joyce wrote. “In short, we had fuel but the construction of the fuel tanks prevented it from getting to the generators.”

So somewhere in the operational chain of command, somebody overlooked the fact that the effective capacity of their fuel tank was less than its actual capacity, because fuel doesn’t levitate. It sounds crazy to me, too, but the alternative is that the truth is even more embarrassing, and this is the story they concocted to cover it up.

Let’s hope that Citigroup knows how to measure the capacity of its backup generators. Some Masters of the Universe.

November 3, 2012

Too Big To Fail Remains Very Real

By Simon Johnson

Prominent voices within the financial sector are increasingly insisting on one point: We have ended “too big to fail.” The idea is simple: through a combination of legislation (the Dodd-Frank legislation of 2010) and supportive regulation (particularly regarding how big banks would be handled in the event of “liquidation”), very large financial institutions are no longer perceived by investors to be too big to fail.

Unfortunately, while tempting, this idea is completely at odds with the facts. The market perception that some financial institutions are “too big to fail” is alive and well. If you want to remove that perception, you need to break up our biggest banks.

In a high-profile paper prepared recently at the behest of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (Sifma), the lobbying group for the securities industry, Federal Financial Analytics Inc. argues that “too big to fail” has effectively been ended.

“U.S. bank holding companies and other financial services firms, regardless of size or the nature of their operations, can no longer be rescued at long-term cost to the federal government or otherwise supported in ways that undermine meaningful market discipline.” (From the first paragraph of the executive summary.)

The implication of this report is that there is no need to push for further reforms on this dimension. But when I discussed the specifics of this issue on a panel at George Washington University last Friday with Karen Shaw Petrou, an author of that report, she conceded that creditors still believe that the government stands behind very large bank holding companies and other big financial companies. (C-Span coverage of the panel discussion is here)

Ms. Petrou’s report deals with what the law and regulations could mean – under her interpretation, which seems close to the Sifma line (although Ms. Petrou speaks only for herself). But we should be more concerned with how the rules are actually understood by investors in financial markets.

You can theorize that “too big to fail” should have been removed by the recent reforms or will be eliminated by the passage of time. But as a practical matter – looking at what investors really believe – “too big to fail” is still with us. This implicit government guarantee lowers the funding costs for very large financial institutions because investors are convinced that debt issued by these firms is less risky than, for example, debt issued by small and medium-sized banks. Ms. Petrou agreed with me on Friday that this is the current situation, although she also argues that there are additional reasons why big banks have a funding advantage (such as more liquidity in the market for their debt).

Overall, I side with Richard Fisher and Harvey Rosenblum of the Dallas Fed, who argue that “too big to fail” is very much here to stay under the current arrangements (see this recent piece I wrote about their work).

In effect, the government is providing a form of insurance that encourages financial institutions to become even bigger – and thus even more likely to be protected by some combination of the Federal Reserve, the Treasury, and other agencies. This is an unfair, nontransparent government subsidy that encourages excessive risk taking and creates a very large potential downside for the nonfinancial side of our economy.

Ms. Petrou points out that there are new legal barriers to some forms of bailout. That’s correct, but the general machinery of potential support – for example, from the Federal Reserve – remains absolutely intact. Sometimes this is discussed in terms of “liquidity” support only, but the line can become blurred between liquidity support and helping a nearly insolvent financial institution. When the Federal Reserve also has the ability to inflate asset prices, for example through conventional or unconventional monetary policy (including buying assets directly), this distinction may sometimes become meaningless.

My conversations with senior officials, recently retired and currently in place, confirms that they are of one mind on the key issue. When the choice is between global calamity on the one hand and unpalatable, unpopular, and perhaps even illegal support for big banks on the other hand, these officials expect to go with the bailout.

Market participants are smart to understand this.

The question is how to take this choice off the table – or at least to make it significantly less probable that we ever reach such a decision point.

In an e-mail exchange on these issues, Ms. Petrou sent this statement:

“Just because markets think they’ll get bailed out doesn’t make it so. This is one more case of markets getting it wrong and doing so with systemic consequence. Regulators should finalize the U.S. resolution regime and, as they do, make it very, very clear what the law says and how much it hurts so that markets prepare to take risk, not continue to expect bail-outs that not only shouldn’t come, but also won’t, at least not here.”

In a recent speech, “On Being the Right Size,” Andrew Haldane from the Bank of England suggests a different emphasis for how we move forward.

It is not the case that the Dodd-Frank reforms were “the biggest kiss” to Wall Street (as Mitt Romney suggested in the presidential debates). Prominent figures on Wall Street fought fiercely against the broad contours of financial reform legislation in 2009-10 and fight now on every line of every detailed regulation; their estimated 3,000 to 5,000 lawyers and lobbyists work very hard and earn a great deal of money for a reason. This is not any kind of kiss that they want.

In the Haldane view – with which I fully concur – the Dodd-Frank changes were steps in the right direction, including the Volcker Rule (limiting what banks can do) and the new resolution authority. The latter empowers the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to create rules governing how any financial institution can fail – with a view to imposing losses on creditors and avoiding broader disruption to financial markets.

The F.D.I.C. has worked hard on resolution issues – and it is no criticism to point out that these rules are as yet unproven and not fully believed by the markets. In the absence of a cross-border resolution framework, these rules also do not adequately cover what would happen if a global megabank went down. (I’m a member of the F.D.I.C.’s Systemic Resolution Advisory Committee; this is unpaid work and our meetings are televised.)

The point is to have multiple fail-safes in the system – do not rely on any one reform too much. You really do not know what will prove effective, particularly as the financial system continues to evolve and the nature of risks changes.

As Mr. Haldane emphasizes, it is therefore entirely complementary to propose a cap on the size of the largest financial institutions.

We need to have a credible commitment to let any financial institution fail – in the sense that it will go out of business, wiping out shareholders and imposing losses on creditors.

But any promise for global megabanks that we would “just let them fail” is completely hollow. Standard or even modified bankruptcy procedures are not a credible threat because of the damage this would cause to other financial institutions and to confidence around the world.

Make banks and other financial institutions small enough and simple enough to fail – this is the point stressed by Messrs. Fisher and Rosenblum.

As Mr. Haldane documents, when measured properly, there are no economies of scale for banks over $100 billion in total assets. As a society, we are not losing anything by imposing a size cap on our largest banks, which currently have assets in excess of $2 trillion. Of course, there are private benefits that are being lost – meaning lower subsidies for the powerful people who run large financial firms.

But we should welcome, not mourn, the elimination of such subsidies.

An edited version of this post previously appeared on the NYT.com’s Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire post, please contact the New York Times.

November 2, 2012

The Economist on Romney’s Fiscal Policy

By James Kwak

It should be no surprise that I am voting for Barack Obama on Tuesday, despite all his flaws and failures of the past four years. There are just too many dimensions on which he is clearly preferable to Mitt Romney. One of the more important ones, on which I spent most of last year (writing White House Burning), is fiscal policy. And here, since anything I write will be dismissed by many readers as liberal propaganda, is The Economist on the topic:

“Yet far from being the voice of fiscal prudence, Mr Romney wants to start with huge tax cuts (which will disproportionately favour the wealthy), while dramatically increasing defence spending. Together those measures would add $7 trillion to the ten-year deficit. He would balance the books through eliminating loopholes (a good idea, but he will not specify which ones) and through savage cuts to programmes that help America’s poor (a bad idea, which will increase inequality still further). At least Mr Obama, although he distanced himself from Bowles-Simpson, has made it clear that any long-term solution has to involve both entitlement reform and tax rises. Mr Romney is still in the cloud-cuckoo-land of thinking you can do it entirely through spending cuts: the Republican even rejected a ratio of ten parts spending cuts to one part tax rises.”

That’s just about the same summary I would have written.

Why Do People Think the Race Is a Tossup?

By James Kwak

There’s been a minor controversy in the blogosphere not about whether Obama or Romney should be president, and not about whether Obama or Romney is ahead in the polls, but about the esoteric question of whether one should interpret the polls to mean that Obama is the favorite or that the race is a “tossup.” This debate has largely swirled around Nate Silver, who aggregates polling data, recalculates confidence intervals, and incorporates other factors (drawn from analysis of previous elections), and for the past few weeks has rated Obama as having about a 60–80% chance of winning the election. In response, various members of the pundit class have argued that the national polls show a tied race, polls can’t predict the future, or even that since both sides (supposedly) think each has a 50.1 percent chance of winning, their chances must be equal. (See Felix Salmon for a summary.)

Silver has responded to all of the coherent objections that might be made to his forecast, in detail. But what’s at work here isn’t a reasoned debate about how to interpret polls. It’s sheer innumeracy, pure and simple. The statement that Obama has about a 75–80 percent chance of winning is roughly equivalent to the statement—which no one contests—that his average lead in Ohio is about 2–3 points, once you take the confidence interval into account. As Silver has said, it’s analogous to the statement that a team that’s ahead by a field goal deep in the fourth quarter has a better chance of winning than the team that’s behind; no one would call that game a “tossup,” even though either team could win. Even if you can’t predict the next turnover or breakaway running play, that wouldn’t lead you to believe the three-point lead is irrelevant.

It’s the same thing we saw in Moneyball—people who can’t understand numbers claiming that numbers have no practical value. Unfortunately, in political journalism the sample size is so small and the monetary stakes are so low that the incoherent innumerates will never be drummed out of the marketplace.

October 29, 2012

What the Federal Government Does

By James Kwak

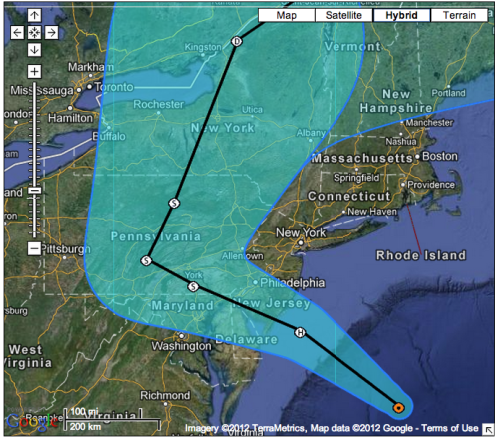

Now is as good a time as any to remind people of who provides all those detailed projections of where Hurricane Sandy is going to hit and how strong it’s going to be: the federal government. No matter how you get your weather news—local TV or radio, The Weather Channel, AccuWeather, whatever—hurricane forecast information originally comes from the National Hurricane Center, which is part of the National Weather Service. The raw data come in part from the Hurricane Hunters, the pilots who fly planes into hurricanes, who are part of the Air Force Reserve and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The computer models that predict where hurricanes are going to strike are developed by the NHC.

In August 2011, Simon and I were on vacation with our families in Southern Florida as Hurricane Irene was approaching the East Coast. Simon had the idea of using government weather services as the example to lead off chapter 4 of White House Burning, “What Does the Federal Government Do?” I like this example because almost everyone agrees that the federal government should be engaged in disaster prevention, disaster relief, and even weather forecasting. In 2005, Rick Santorum proposed a bill that would have prevented the National Weather Service from providing weather forecasts to the public—but he insisted that the NWS should gather weather data and provide it to private companies so that they could make money off of it. (AccuWeather is based in Pennsylvania, Satorum’s state, by the way.)

In August 2011, Simon and I were on vacation with our families in Southern Florida as Hurricane Irene was approaching the East Coast. Simon had the idea of using government weather services as the example to lead off chapter 4 of White House Burning, “What Does the Federal Government Do?” I like this example because almost everyone agrees that the federal government should be engaged in disaster prevention, disaster relief, and even weather forecasting. In 2005, Rick Santorum proposed a bill that would have prevented the National Weather Service from providing weather forecasts to the public—but he insisted that the NWS should gather weather data and provide it to private companies so that they could make money off of it. (AccuWeather is based in Pennsylvania, Satorum’s state, by the way.)

There’s a strong case to be made that hurricane research is one area where a small amount of taxpayer spending has had huge public benefits. That argument is made by Jeff Masters of Weather Underground. I was going to put it into White House Burning, but I didn’t think one of his sources said what he wanted it to say. Still, as I discussed in a previous post, it is highly likely that more accurate forecasts have saved tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in unnecessary evacuations for each large hurricane.

What do Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan think about taxpayer-funded hurricane research? We don’t know what Mitt Romney thinks because we don’t know what he thinks about anything (wait . . . this month he’s a moderate, so he’s probably for it . . . but isn’t he in favor of private sector innovation, so maybe he’s against it . . . how does his head not explode?). But we know what Paul Ryan thinks about it because the House tried to cut Hurricane Hunter funding by 40 percent in 2011. Let’s see what he has to say about that on the campaign trail.

The bigger issue is that Romney-Ryan calls to cut government spending run into the problem that most government spending is on things that most people like, such as disaster forecasting and prevention. This is why they can’t say in particular what programs they would cut, just like they can’t say what tax deductions they would eliminate, because that would be obviously stupid or unpopular. Instead, when they open their mouths to talk about government spending, they want more of it, like Mitt Romney saying we need an even bigger navy. (By contrast, Robert Gates, a Republican defense secretary, thought that eleven aircraft carrier groups were more than enough in a world where no other country had more than one—and that’s already stretching the definition of aircraft carrier group.)

Romney-Ryan is all about lower tax rates, more spending on things they like, and nothing (tax increases or spending cuts) that would actually make anyone worse off. What’s wrong with this picture?

October 26, 2012

The Effects of Golden Parachutes

By James Kwak

The indefatigable Lucian Bebchuk has written another empirical paper (Dealbook summary), this time with Alma Cohen and Charles Wang, on the impact of golden parachutes (agreements that pay off CEOs generously in case of acquisition by another company) on shareholder value.

Looking just at the question of whether a company is acquired and for how much, they find out that golden parachutes work about how you would expect. Companies whose CEOs have golden parachutes are more likely to get acquisition offers and are more likely to be acquired, presumably because their CEOs are les likely to contest takeovers. On the other hand, these companies tend to sell for lower acquisition premiums, again because their CEOs are more likely to be happy to be bought out.

“So far, so good,” Bebchuk writes. But the problem is that when you take a longer view, golden parachutes appear to be bad for shareholder value. Companies that adopt golden parachutes have lower risk-adjusted stock returns than their peers—despite the fact that they are more likely to be acquired. Some other factor is outweighing the positive effect (for the stock price) of more frequent takeovers.

Bebchuk proposes one explanation: Golden parachutes make being acquired relatively painless to CEOs. Therefore, they are less afraid of being acquired; and, therefore, they are less concerned about maximizing shareholder value in the first place.

Here’s another possibility: Companies are more likely to grant golden parachutes to their CEOs if they have: (a) CEOs who care more about maximizing their personal wealth than about their companies; (b) boards who are more concerned about doing favors for the CEO than about doing what’s right for the company; or (c) both. Those are not the kinds of companies you want to be investing in, since they’re likely to screw up all sorts of other things in addition to their executive compensation policies.

October 25, 2012

Bipartisan Trouble Ahead

By Simon Johnson

In Washington today, “bipartisan” is a loaded term. The traditional usage of bipartisan is an agreement across the usual political divide – sometimes a good idea and in many cases the only way to get things done. But a darker meaning applies all too frequently – a group in which the members, irrespective of party affiliation, are very close to special interests and work to advance an agenda that helps a few powerful people while hurting the rest of us.

Financial deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s was pushed by both Democrats and Republicans. It reached its apogee when Alan Greenspan, a Republican, was chairman of the Federal Reserve and Robert Rubin, a Democrat, was Treasury secretary. Bill Clinton was president; Newt Gingrich was speaker of the House.

This is probably why President Obama and Mitt Romney shied away this fall from the issue of who was responsible for the financial crisis that brought us the deep recession and slow recovery of the last five years. Both political parties share culpability for allowing parts of the financial sector to take excessive risk while financing themselves with a great deal of debt and relatively little equity.

In this context, the new Financial Regulatory Reform Initiative of the Bipartisan Policy Center seems eerily familiar.

The introductory white paper published last week reads like a sophisticated manifesto preparing us for another round of deregulation. We have come a long way since the 1990s – and most of it has been downhill. No reasonable person can now espouse the kind of views that Mr. Greenspan repeatedly laid out during his libertarian push to allow banks to become as big and as dangerous as they wished. (In our book, “13 Bankers,” James Kwak and I go through the historical record of deregulation – and Mr. Greenspan emerges as a central character.) Mr. Greenspan’s bipartisan notion – that any financial-sector mess can be cleaned up easily and cheaply – is now completely exploded.

Still, the new initiative, underwritten by the Heising-Simons Foundation, seems likely for three reasons to push strongly for the rollback of important parts of the Dodd-Frank legislation.

First, the white paper frames the entire issue in a way that is incorrect – but highly informative about the attitudes at work: “Evaluating financial regulatory reform requires consideration of the inevitable trade-off between market stability and the combination of innovation, risk-taking and growth” (see Page 6).

There is no such trade-off. Financial crises destroy growth – and for a long period of time. If you want to undermine American productivity, as well as the power and prestige of the United States, step back and allow the financial sector to go crazy again. In the last decade, the United States lost its stability and its growth. It’s too bad the presidential candidates were not pressed on this point during the recent debates, and particularly on the cost of the crisis, estimated by Better Markets to be more than $12.8 trillion.

Second, of the task force’s 14 members, an overwhelming majority are very close to the industry’s way of thinking. Six are lawyers whose practices – according to their biographies on the Financial Regulatory Reform Initiative’s Web site — involve working with major financial-sector players. Two of them, Annette L. Nazareth and H. Rodgin Cohen, are among the most well-known advocates for Big Finance (see this profile of Ms. Nazareth from Bloomberg Businessweek). Another of these lawyers is John C. Dugan, comptroller of the currency from 2005 to 2010, head of an agency famous for being very friendly to the banks under its supervision. Mr. Dugan also features in “13 Bankers” – not as influential as Mr. Greenspan but still a person very much identified with deregulation and nonregulation.

Another two task-force members are senior figures at companies – Oliver Wyman and PricewaterhouseCoopers – for which Wall Street firms are important clients. Robert K. Steel is also on board; he is currently a deputy mayor in New York City and was previously chief executive of Wachovia and worked at Goldman Sachs for more than 30 years. Mark Olson, currently with Treliant Risk Advisors, is a past president of the American Bankers Association.

Powerful people in the industry were, naturally, happy to have regulators back off and supervision to become super-light in the past. In fact, they lobbied long and hard to make this happen – including, for example, the right to use their own risk models in calculating how much equity capital they needed to have. I hear the same arguments today.

With 10 of the 14 initiative members so close to big players in the financial sector, can this initiative in fact be “independent, objective and fact-based”? Their clients do not want to be regulated effectively.

Not everyone in this group should be considered close to big banks or Wall Street more generally. Three distinguished academicians are involved – John C. Coffee Jr., James D. Cox and Thomas H. Jackson. We shall see to what extent they can provide a counterweight to the financial sector. There is also one independent member from outside the academic world, Eric Rodriguez, vice president at the National Council of La Raza, which the Bipartisan Policy Center describes as “the largest national Hispanic civil rights and advocacy organization in the United States.”

If the organizers of the initiative were seeking experienced industry professionals, they should have invited the former insiders who form Occupy the S.E.C. — and who recently submitted another impressive letter on the Volcker Rule in response to a request from Representative Spencer Bachus, Republican of Alabama and chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, for “alternatives” to it.

Third, while the internal governance structure of the initiative is somewhat unclear, there is no reason to be optimistic about the decision-making process and the work product. The directors, Martin Neil Baily and Phillip Swagel, are former senior government officials who now work at think tanks (Mr. Baily is at Brookings and Mr. Swagel at the American Enterprise Institute and the Milken Institute) and a university (Mr. Swagel’s primary appointment is on the faculty of the University of Maryland).

Both are thoughtful people who are open to discussion. Mr. Swagel recently invited me to a forum at the Milken Institute where we debated – along with Harvey Rosenblum of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and Peter Wallison of the American Enterprise Institute – whether big banks should be forced to become smaller (and, in my view and Mr. Rosenblum’s view, less dangerous). Mr. Swagel and Mr. Wallison strenuously opposed the proposition (you can watch this discussion on the C-Span archive).

Two senior advisers, whose role is not made clear on the Web site, seem very similar to most task-force members in terms of their background and current work. Gregory P. Wilson worked in the past with the Financial Services Roundtable (a lobbying group for large banks) and is still an external adviser to the group. James C. Sivon, a top banking lawyer, is a former senior executive at the Association for Bank Holding Companies.

The director of the initiative is Aaron Klein, a former senior Treasury official (under President Obama) who previously worked for Senator Chris Dodd, Democrat of Connecticut. Mr. Klein wrote the white paper, along with Mr. Baily and Mr. Swagel. It is striking – and disappointing – to see such figures endorse the idea of a “stability-growth trade-off” (see Page 7) for modern financial regulation in the United States.

This is the same attempted frame for the issues that I hear regularly from industry lobbyists and their lawyers (for example, at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission hearing on the Volcker Rule in May).

This is entirely the wrong way to look at our financial sector, including the global megabanks that have come to predominate. This particular special interest has become too powerful – and is working hard to repeal the restrictions that can limit its ability to damage the economy again.

Subsidizing, with implicit guarantees, the too-big-to-fail financial institutions is unfair and dangerous. Such subsidies distort and destroy markets. They undermine stability and make it harder to sustain growth. Fewer people will benefit from the growth that we do have.

Let’s be honest: Everyone would like an arrangement in which they personally get the upside and the taxpayer gets the downside. Imagine how much fun it would be to visit Las Vegas on that basis – and the size of the bets you would make.

Asked to comment, Mr. Swagel said, “It is easy and wrong to say that efforts to change Dodd-Frank are to weaken it.” He suggested that this bipartisan initiative could improve financial regulation and that such changes would be good for the economy and for all Americans.

My view is that, unfortunately, the Financial Regulatory Reform Initiative of the Bipartisan Policy Center seems likely to side with industry lobby groups on all substantive questions.

I hope I’m wrong, but their initial paper and the task-force membership suggests that they will just be another cog in the vast Wall Street influence machinery that has come to dominate Washington.

An edited version of this post previously appeared on the NYT.com Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

October 24, 2012

Incentive Effects of Higher Wages

By James Kwak

My Atlantic column this week is on a familiar theme: why don’t Barack Obama and Democrats provide an clear alternative vision to the Romney-Ryan state of nature, instead of slowly stumbling along in the Republicans’ wake? But it also brings up a question that I haven’t seen before.

The theoretical argument against higher tax rates is that it reduces the incentive to work because it changes the terms of the tradeoff between labor and leisure. That is, higher taxes reduce your effective returns from labor, while your returns from leisure remain constant, so you will substitute leisure for labor.

In the long term, however, real wages tend to go up; even in the past three decades, which have generally been bad for labor (and good for capital), they’ve gone up by about 11 percent. If tax rates remain constant, that should increase the effective returns to labor, causing people to substitute labor for leisure (i.e., work more). Put another way, you could increase tax rates and keep the tradeoff between labor and leisure constant.

I generally don’t buy these pure theoretical arguments, but my point is that if you believe that higher taxes reduce labor supply through the substitution effect, then you should acknowledge that the effect of higher taxes could be swamped by growth in real wages.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers