Simon Johnson's Blog, page 27

April 19, 2013

Fatal Sensitivity

By James Kwak

One more post on Reinhart-Rogoff , following one on Excel and one on interpretation of results.

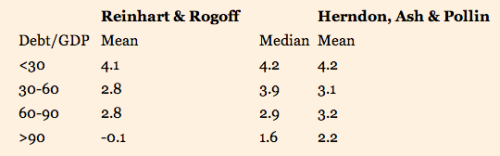

While the spreadsheet problems in Reinhart and Rogoff’s analysis are the most most obvious mistake, they are not as economically significant as the two other issues identified by Herndon, Ash, and Pollin: country weighting (weighting average GDP for each country equally, rather than weighting country-year observations equally) and data exclusion (the exclusion of certain years of data for Australia, Canada, and New Zealand). According to Table 3 in Herndon et al., those two factors alone reduced average GDP in the high-debt category from 2.2% (as Herndon et al. measure it) to 0.3%.*

In their response, Reinhart and Rogoff say that some data was “excluded” because it wasn’t in their data set at the time they wrote the 2010 paper, and I see no reason not to believe them. But this just points out the fragility of their methodology. If digging four or five years further back in time for just three countries can have a major impact on their results, then how robust were their results to begin with? If the point is to find the true, underlying relationship between national debt and GDP growth, and a little more data can cause the numbers to jump around (mainly by switching New Zealand from a huge outlier to an ordinary country), then the point I take away is that we’re not even close to that true relationship.

In their response, Reinhart and Rogoff also argue that it is correct to weight by country rather than by country-year. Their argument is basically that weighting by country-year would overweight Greece and Japan, which had many years with debt above 90% of GDP. Herndon et al. recognize this point:

“RR does not indicate or discuss the decision to weight equally by country rather than by country-year. In fact, possible within-country serially correlated relationships could support an argument that not every additional country-year contributes proportionally additional information. . . . But equal weighting by country gives a one-year episode as much weight as nearly two decades in the above 90 percent public debt/GDP range.”

Both weighting methods are flawed. (Country-year weighting is only flawed if there is serial correlation, which there probably is; if the U.K.’s nineteen years with debt greater than 90% of GDP were independent draws, then it should be weighted 19 times as much as a country with only one such year.) But this brings me to the same point as above: if your results depend heavily on the choice of one defensible variable definition rather than another, at least equally defensible definition, then they aren’t worth very much to begin with.

Here’s another way to put it. Let’s concede the weighting point for the sake of argument. If Reinhart and Rogoff had not made any spreadsheet errors in their original paper—that is, if the only factors at issue were country weighting and data exclusion—they would have calculated average GDP growth in the high-debt category of 0.3%. If they then added the additional country-years as they expanded their data set, while sticking with their preferred weighting methodology, that figure would have jumped to 1.9%—and the 90% “cliff” would have completely vanished. (See Herndon et al., Table 3.) What happened is that Reinhart and Rogoff’s choice to weight by country rather than country-year makes their method extremely sensitive to the addition of new data.

The question to ask is this: If a method produces results that can drastically change by the addition of a few more data points, are those results worth anything? The answer is no.

April 18, 2013

Are Reinhart and Rogoff Right Anyway?

By James Kwak

One more thought: In their response, Reinhart and Rogoff make much of the fact that Herndon et al. end up with apparently similar results, at least to the medians reported in the original paper:

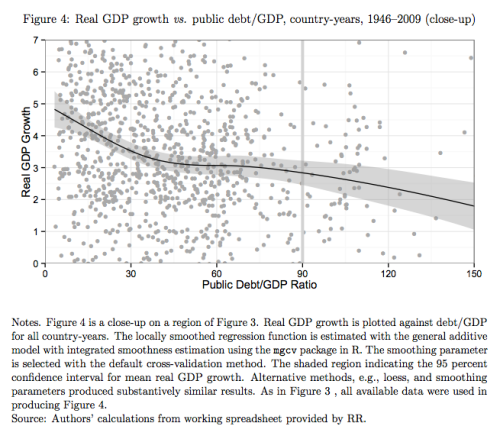

So the relationship between debt and GDP growth seems to be somewhat downward-sloping. But look at this, from Herndon et al.:

Yes, we still have that downward slope. But two things:

1. There’s no cliff at 90 percent, which was the central finding of the original paper. This is the second sentence of that paper:

“Our main result is that whereas the link between growth and debt seems relatively weak at ‘normal’ debt levels, median growth rates for countries with public debt over roughly 90 percent of GDP are about one percent lower than otherwise; average (mean) growth rates are several percent lower.”

2. Aren’t we only supposed to be interested in empirical results that are significant? What the figure from Herndon et al. says, in their words, is this:

“Between public debt/GDP ratios of 38 percent and 117 percent, we cannot reject a null hypothesis that average real GDP growth is 3 percent.”

I find it hard to agree with Reinhart and Rogoff when they say, “We do not, however, believe this regrettable slip affects in any significant way the central message of the paper.”

More Bad Excel

By James Kwak

In 1975, Isaac Ehrlich published an empirical study purporting to show that the death penalty saved lives, since each execution deterred eight murders. The next year, Solicitor General Robert Bork cited this study to the Supreme Court, which upheld the new versions of the death penalty that several states had written following the Court’s 1973 decision nullifying all existing death penalty statutes. Ehrlich’s results, it turned out, depended entirely on a seven-year period in the 1960s. More recently, a number of studies have attempted to show that the death penalty deters murder, leading such notables as Cass Sunstein and Richard Posner to argue for the maintenance of the death penalty.

In 2006, John Donohue and Justin Wolfers wrote a paper essentially demolishing the empirical studies that claimed to justify the death penalty on deterrence grounds. Donohue and Wolfers attempted to replicate the results of those studies and found that they were all fatally infected by some combination of incorrect controls, poorly specified variables, fragile specifications (i.e., if you change the model in minor ways that should make little difference, the results disappear), and dubious instrumental variables. In the end, they found little evidence either that the death penalty reduces or increases murders.

Now the macroeconomic world has its version of the death penalty debate, in the famous paper by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, “Growth in a Time of Debt.” Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash, and Robert Pollin released a paper earlier this week in which they tried to replicate Reinhart and Rogoff. They found two spreadsheet errors, a questionable choice about excluding data, and a dubious weighting methodology, which together undermine Reinhart and Rogoff’s most widely-cited claim: that national debt levels above 90 percent of GDP tend to reduce economic growth.

I’ve never been a big fan of Reinhart-Rogoff. In White House Burning, we cited their main result but added (p. 151),

“It is hard to know what it means for the United States because even their findings for advanced economies are the averages over sixty years of twenty different countries—nineteen of which did not enjoy the particular benefits of issuing the world’s reserve currency.”

Now it turns out that the averages were wrong. To see how, you can read Herndon et al. (it’s very short and readable) or the excellent post by Mike Konczal. If you don’t want to do that, there are four basic issues:

The 2010 Reinhart and Rogoff paper excluded data for certain countries and years that, when included, increase mean growth for debt levels greater than 90 percent. (In their response, Reinhart and Rogoff say that those country-years were not available when they did the original paper.)

The results were averaged by country and then the country averages were themselves averaged. The problem here is that, for example, New Zealand only had debt above 90 percent in one year, and in that year its growth was –7.6 percent—but since only ten countries ever had debt over 90 percent, that outlier constituted one-tenth of the average.

Their spreadsheet formula accidentally omitted several countries; including those countries increases the average growth level for debt levels over 90 percent.

One figure—New Zealand’s—was mistranscribed from one spreadsheet to another; correcting that mistake slightly raises the average growth level.

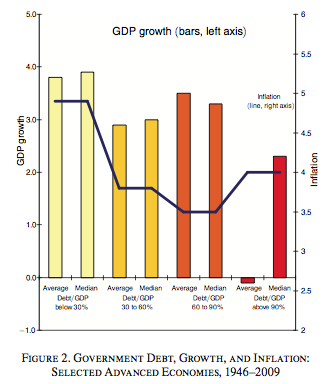

Leaving aside the Excel problem for now, I think this points to a weakness of the original methodology. The paper was, technically speaking, extremely simple: take all the country-years, divide them into four groups by debt level, and average within each group. I thought at the time that if an economics graduate student tried to submit this as part of a dissertation, it would never be accepted. I remember looking at this chart and thinking: So what? Does that prove anything? How do I know that this is significant—especially since the mean and the median are so different? (Usually if the mean is very different from the median, it is being dragged up or down by some huge outlier.)

Like most people, I think, I thought they were averaging by country-year, not country. Averaging by country obviously makes the results even more sensitive to outliers. Reinhart and Rogoff claim in their response that this is a standard approach; maybe it is. But this is what the paper says (emphasis added):

“The annual observations are grouped into four categories, according to the ratio of debt to GDP during that particular year as follows: years when debt to GDP levels were below 30 percent (low debt); years where debt/GDP was 30 to 60 percent (medium debt); 60 to 90 percent (high); and above 90 percent (very high). The bars in Figure 2 show average and median GDP growth for each of the four debt categories. Note that of the 1,186 annual observations, there are a significant number in each category, including 96 above 90 percent.”

I think the most natural reading of this passage is that they were averaging individual country-year observations, not countries.

The other surprising thing, of course, is that they were using Excel (or some other spreadsheet program)—something that I wrote about recently. The attraction of Excel is that it’s visually intuitive, it’s powerful, and it’s fast. The problem is that it’s very easy to make mistakes, it doesn’t have any usable kind of versioning, and there’s no good way to proofread or test it. As Herndon et al. write with considerable understatement, “For econometricians a lesson from the problems in RR is the advantages of reproducible code relative to working spreadsheets.” And if you’re going to use Excel for anything important (like counseling economic policymakers), you’d better be damn good at it. For example, you shouldn’t be manually copying numbers from one tab to another (an error shared by Reinhart and Rogoff with the risk management department of JPMorgan’s Chief Investment Office).

This raises another issue. Programming is getting easier and easier, but it’s hard to do well. Economics these days depends heavily on programming. It seems to problematic to me that we rely on economists to also be programmers; surely there are people who are good economists but mediocre programmers (especially since the best programmers don’t become economists). If you crawl through a random sample of econometric papers and try to reproduce their results, I’m sure you will find bucketloads of errors, whether the analysis was done in R, Stata, SAS, or Excel. But people only find them when the stakes are high, as with the Reinhart and Rogoff paper, which has been cited all around the globe (not necessarily with their approval) as an argument for austerity.

April 15, 2013

“Gut Instinct Doesn’t Matter”

By James Kwak

I’m no fan of the genre of CEO interviews published in the Sunday Times. But this past Sunday’s CEO-of-the-week column featured Marcus Ryu, a good friend and someone I’ve worked with at three different companies.

Marcus is not only very smart and someone who really knows what it’s like to build a company from the ground up, but he’s also someone who has thought very hard about what it takes to succeed as a company and what a company needs in its CEO. Unlike many CEOs, he doesn’t believe in gut instinct or the magical ability to judge character. He believes that success in business is hard and, as I’ve heard him say many times, there never is a day when suddenly everything becomes easy. If you are or want to be a CEO someday, I recommend it.

April 2, 2013

Memo to Employers: Stop Wasting Your Employees’ Money

By James Kwak

Now that I’m a law professor, people expect me to write law review articles. There are some problems with the genre—not least its absurd citation formatting system and all the fetishism surrounding it—but it’s not a bad way to make arguments about how and why the law should change in ways that might actually help people.

That was my goal in my first law review article, “Improving Retirement Options for Employees, which recently came out in the University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law. The general problem is one I’ve touched on several times: many Americans are woefully underprepared for retirement, in part because of a deeply flawed “system” of employment-based retirement plans that shifts risk onto individuals and brings out the worse of everyone’s behavioral irrationalities. The specific problem I address in the article is the fact that most defined-contribution retirement plans (of which the 401(k) is the most prominent example) are stocked with expensive, actively managed mutual funds that, depending on your viewpoint, either (a) logically cannot beat the market on an expected, risk-adjusted basis or (b) overwhelmingly fail to beat the market on a risk-adjusted basis.

People in all fields often say that some outcome is bad—here, plan participants pay a weighted average of 74 basis points in expenses for their domestic stock funds, not counting the extra transaction costs incurred by actively managed funds—and say that someone should change the law. While law professors sometimes say that the solution is for Congress to pass a new statute, there are other ways of accomplishing an objective. In the paper I use a common device in the profession: I argue that including actively managed funds, in asset classes where everyone knows that index funds are cheaper and likely to do better than most active funds, may already be against the law (depending on how carefully those funds are selected). In particular, it violates the existing fiduciary duty of employers and plan trustees to invest participants’ money prudently.

The argument is moderately involved, and involves statutory and regulatory detours into such things as section 404(c) of ERISA and the corresponding safe harbor implemented by Department of Labor regulations. But the ultimate point is that plan participants should be able to sue their plan fiduciaries for breaching their duties, and courts could already rule in their favor. Since the law is admittedly not entirely clear-cut, I recommend that the Department of Labor should clarify its guidelines under ERISA (which could be done without Congressional action) to make it clear that actively managed funds create potential liability for plan fiduciaries. The likely result is that most plans would shift to index funds in order to avoid liability, investor costs would fall by about 80 percent, and, in aggregate, investors would do slightly better than before even on a gross (before fees) basis.

This change would also solve the problem of plan trustees who also happen to be mutual fund companies stuffing retirement plan investment menus with their own funds—particularly their most poor-performing funds—which is the problem I wrote about in my Atlantic column last week.

I should add that I do understand that there probably are some fund managers who can beat the market on an expected, risk-adjusted basis. I’ve seen the papers, and I’m convinced that there are more people who beat the market than can be explained by dumb luck.* (There are also far more people who trail the market than can be explained by dumb luck.) But the fact is that, in aggregate, the pursuit of “alpha” is value-destroying, whether the search is conducted by individual investors or by trustees of employer-sponsored retirement plans. The government should not be subsidizing a vast operation that wastes ordinary people’s money. Index funds would give Americans retirees more money and asset management companies less money. From a public policy perspective, that’s a good thing.

* I took empirical law and economics with Ian Ayres and John Donohue. In one class, Ian asked if any of us could think of a policy issue on which we had changed our position because of an empirical paper. Most people had trouble thinking of one. That is, if you think that the minimum wage increases unemployment, you will not be convinced otherwise by any number of papers, and vice versa. Whether there are people who can beat the market is one big issue on which I have changed my mind. I used to believe that no one could beat the market, essentially for the reasons outlined by Burton Malkiel in A Random Walk Down Wall Street. Now I think there are people who can beat the market, but they are hard to find and for most people it’s not worth trying.

March 31, 2013

Go For Gold

By Simon Johnson, April 1, 2013

In both 13 Bankers (2010) and White House Burning (published 2012, paperback just came out) James Kwak and I weighed the merits of going back on a global gold standard. In those books, we ended up siding with the prevailing fiat currency system – in which money is backed by nothing more than your confidence in central banks.

In the light of recent events – in the US and in Europe – I feel we should reconsider the arguments. On balance, I am now in favor of going back on gold for ten main reasons.

First, gold worked well for Winston Churchill in 1925.

Second, we have all had about as much as we can take with regard to us – i.e., the taxpayer – bailing out banks. Let’s go back on gold and turn the tables, as Grover Cleveland did in 1895, when JP Morgan (the man) was forced to bailout the US government with the famous “gold loan”.

Of course, the bankers could let us just go bust. But that would hardly be in their best interests. And the beauty of the gold standard is that it ties the hands of the government – forcing big banks to either lend at generous terms or watch their franchise value collapse (with the economy).

Third, eurozone officials have created serious confusion on the order of priority for claims when a European bank gets into trouble. With the gold standard it’s easy in a way that everyone can understand – no one gets anything when a bank collapses (and even less when world trade disintegrates).

Of course, in order to be truly effective as a way to stabilize the world’s economy, the return to gold would have to be combined with making deposit insurance illegal everywhere other than in Germany. The good news is that on the latter point, Jeroen Dijsselbloem and the Eurogroup of finance ministers are already far down the garden path.

Fourth, let’s face it – almost all the growth the world has experienced since 1945 has proved ephemeral. And inflation has increased almost without limit since President Nixon brought the final bonds between dollar and gold in 1971. We have experienced undeniably the worst 60 years in human economy history – all since we turned our backs on gold. The sirens of gold are just as right now as they have always been.

Fifth, of course the nay-sayers always bring up the Great Depression, and argue that the gold standard played an integral role in both the banking collapses and the breakdown of international payments and trade. But seriously – how many of today’s supposedly astute observers were really there, and therefore know anything at all about what happened?

We should all apply the principles recently established by JP Morgan (the company) with regard to studies of “too big to fail” subsidies – if there is any margin of error in the estimates of any kind, we should disregard the evidence fully. This will greatly simplify many things, including science, the pages of our leading newspapers, and refereeing for academic journals.

In any case, reports of the severity of the economic slowdown in the 1930s have been greatly exaggerated. Among other things, that decade provided ample time to rest up before the hard working 1940s.

Sixth, with regard to the conventional concern that “there is not enough gold to accommodate world growth without a falling price level”, we should simply apply some of the more compelling modern financial innovations. We can create synthetic gold – for example using iron pyrite – and have governments trade that, building on the “success” of existing gold exchange-traded products that do not in fact involve any gold.

Seventh, the fact that high profile people such as Glen Beck endorse gold should encourage us in the same direction. After all, Mr. Beck is a busy person with many well remunerated activities. If he chooses to spend time with gold, the market is telling us something.

Eighth, you should read this book by Gillian Tett. The title tells you everything you need to know about many things.

Ninth, while the Financial Services Roundtable has not weighed in yet on this issue, once they figure out the subsidies angle, they will be all over it (hint: those gold loans to the government are highly profitable and debtors more generally get crushed as a matter of routine). Anyone opposing the lobby will be ridiculed, rolled over, or bought out, so why not get on board now?

Tenth, currency convertibility should be suspended every April 1st at least momentarily. That might help remind us of the crazy things we have done in pursuit of a supposedly more stable currency and more prosperous financial system.

March 26, 2013

Gee Whiz, Incentives Matter

By James Kwak

Back in the heady days of the financial crisis, I used to recommend Planet Money as a good way for non-specialists to learn about some of the basic economic and financial issues involved. Over the years, I’ve become less thrilled with the show, for reasons that will become obvious below. In particular, whenever Ira Glass dedicates a full This American Life episode to a Planet Money story, I cringe nervously, but I listen to it anyway, since, well, I’ve listened to just about every TAL episode ever, and I’m not about to stop now.

But I can’t let this weekend’s episode, on Social Security disability benefits, pass without comment. In it, Chana Joffe-Walt “investigates” the Social Security disability program, first by visiting Hale County in Alabama, where 25% of all working age adults are receiving disability benefits, and then by talking to different types of people (lawyers and public sector contractors) who help people apply for benefits.

The worst part of the episode comes at the end, where Joffe-Walt claims that the Supplemental Security Income program, by paying benefits to poor families with disabled children, discourages children from doing well in school and from seeking work as adults, because either would cause them to lose their benefits. (“One mother told me her teenage son wanted to work, but she didn’t want him to get a job because if he did, the family would lose its disability check.”) On that topic, I’ll just outsource the rebuttal to Media Matters, citing the National Academy for Social Insurance and the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, among others.

But the story as a whole suffers from the same kind of facile extrapolation from the individual story to national policy. The first half (on Hale County) winds up to the following punch line: There are lots and lots of people receiving disability benefits, and they receive lots and lots of money in aggregate, because there aren’t enough jobs where you can sit down. Or, rather, that’s Joffe-Walt’s conclusion from talking to people in Alabama: the reason they can’t even imagine working with back pain, and she can, is that they don’t see any jobs around where you can sit down.

Only then, as she pulls back the camera, the problem becomes the decline of American manufacturing, lost jobs, and newly unemployed factory workers without the skills they need to find new jobs. But which one is it? Is it too many jobs where people stand up (the problem in Hale County) or not enough (the decline of manufacturing)? Probably the latter: the story makes more sense as one where one set of jobs goes away, leaving people unable to get the jobs that are now available, and they turn to disability insurance instead. But that doesn’t explain Hale County, where there are no sit-down jobs.

Then there’s the weird way the whole episode treats welfare reform. “Ending welfare as we know it” comes up in a couple of places: first as a positive example of what we should be doing (moving people from passively receiving benefits to working), and later as a cause of the rise in disability claimants. On the latter point, Joffe-Walt cites the fact that federal welfare funding declined, shifting the burden to the states, which gave the states the incentive to push people off welfare and onto disability. True enough. But she overlooks the big story. Federal welfare reform set lifetime benefit limits, meaning that, after a few years, you get completely cut off. After some welfare recipients got jobs, this was the factor that ensured that welfare rolls would go down. Many people who couldn’t work and got welfare now can’t work and get disability. That’s a good thing—especially if the alternative is pushing them onto the streets.

Leaving all that aside, though, the story boils down to the idea that disability benefits are valuable, so people are trying to get them, framed as some sort of epiphany. “Holy cow, Batman, incentives matter!” But this is just social insurance 101. When designing programs that help poor and disadvantaged people, we already try not to reduce their incentives to work too much. That’s why programs phase out over income ranges, that’s why we have the Earned Income Tax Credit, that’s why we have a debate every time long-term unemployment benefits have to be reauthorized, and so on. Is this some sort of national scandal? No. There are people who are disabled and can’t work, they are entitled to a decent existence, the rest of us who can work should pay for it, and there is going to be a gray area where some people will be motivated to try to get into the program. That’s life.

And is the existence of disabled people some sort of huge new insight into the evolution of the American economy? Again, no. Joffe-Walt claims that the 14 million people receiving benefits outnumber the people who are unemployed and are completely invisible to economists. It’s true the newspapers don’t publish monthly disability figures like they do unemployment statistics. But look at this:

That’s the employment-to-population ratio, from the incredibly useful Calculated Risk. Since the denominator is all working-age people, this chart reflects any growth of disability recipients. And do you see some huge invisible force that is pushing down the employment ratio? I don’t think so. This chart tells the usual story we all know. The economy was very strong in the late 1990s, probably unsustainably so (with unemployment below the long-term sustainable rate, according to the macro guys). We had a recession, and then employment recovered to roughly the sustainable rate. Then we had the financial crisis and a huge fall in employment. Sure, a rise in disability rates could mean the employment-to-population ratio is lower than it otherwise would have been. But it’s not a new way of thinking about the economy. And if we’re getting better at diagnosing mental illness and providing benefits to people with mental illness, that’s a good thing.

I was going to end by trying to explain why I love This American Life and used to like Planet Money (see, for example, the episode where they talked to a chemist about why gold ends up becoming the basis for money in many developing societies) but don’t like episodes like this one. But Ira Glass is one of the savviest people in radio or any medium, so he can figure out what’s going on with the show he co-owns.

March 22, 2013

The Value of “Top Talent”

By James Kwak

From a Wall Street Journal article about The Children’s Investment Fund:

“[The fund] lost 43% in 2008, among the worst losses by a hedge-fund that year.”

“Both investors and employees defected during the crisis, with top talent leaving to start hedge funds of their own.”

“But with a 30% return in 2012 and a 14% gain this year, TCI has crossed its high-water mark.”

Makes you think.

March 21, 2013

Sir John Peace Should Resign As Chairman of Standard Chartered Bank

By Simon Johnson

On Thursday, March 21, Sir John Peace conceded that he lied to investors on March 5, 2013 when he said of Standard Chartered Bank,

“We had no willful act to avoid sanctions; you know, mistakes are made – clerical errors – and we talked about last year a number of transactions which clearly were clerical errors or mistakes that were made…”

Specifically, he now says that these remarks were “both legally and factually incorrect” because Standard Chartered had previously conceded that it deliberately laundered money.

In plain English, what Sir John said is called lying. Or, if you prefer the language of securities lawyers, he engaged in deliberate misrepresentation. He also violated Standard Chartered’s deferred prosecution agreement with US authorities.

Here is the full statement today.

Sir John should resign immediately as chairman of Standard Chartered.

Look carefully at the dates. He lied to investors on March 5 but did not issue this correction until March 21 – apparently after US regulators threatened the bank with renewed prosecution.

If the March 5 remarks were a genuine mistake, Sir John could have retracted them the same day. March 6, 7, and 8 were also pretty much wide open for retractions.

Standard Chartered – in the person of Sir John – has deceived prosecutors, regulators, and the investing public. This is outrageous executive behavior and it cannot be tolerated in a company that holds a US banking license.

If Sir John does not resign, he should be removed by the board of Standard Chartered.

If the bank’s board refuses to act, this will signal that it is not competent to oversee the operations of a global bank.

Senator Elizabeth Warren asked recently: before you lose your banking license,

“How many billions of dollars do you have to launder for drug lords?”

Fed Governor Jerome Powell replied (with the wording from the same Politico article),

“I’ll tell you exactly when it’s appropriate” to consider pulling a bank’s license, he said. “It’s appropriate when there’s a criminal conviction.”

Standard Chartered Bank signed a deferred prosecution agreement which, among other things, requires it to take responsibility for its previously illegal sanction-busting actions.

If the chairman publicly and deliberately denies responsibility – in explicit violation of this agreement – he should step down or be forced out. How can the authorities now have any reasonable confidence that Standard Chartered will comply with the rest of its agreement, including,

“Under the cease and desist order, Standard Chartered must improve its program for compliance with U.S. economic sanctions, Bank Secrecy Act, and anti-money-laundering requirements.”

If Sir John does not go, Mr. Powell and his colleagues should pull the bank’s license.

If under such circumstances the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve finds it cannot take action, then we must consider amending the Federal Reserve Act.

March 13, 2013

Moving the Goalposts

By James Kwak

Ezra Klein yesterday highlighted one of the underlying problems with even apparently informed discussions of deficits and the national debt: the CBO’s “alternative fiscal scenario.” As opposed to the (extended) baseline scenario, which simply projects the future based on existing law, the alternative scenario is supposed to be more realistic. And it is more realistic in some ways: for example, it assumes that spending on Afghanistan will follow current drawdown plans, not a simple extrapolation of the current year’s spending. But the problem is that it has become excessively conservative in recent years—to the point where, as Klein says, “Policy makers, pundits and others almost exclusively use this model to stoke Washington’s deficit anxieties.”

The basic problem is that the alternative fiscal scenario simply assumes, without further support, that laws will mysteriously change in ways that reduce tax revenue and increase spending (relative to current law). As I put it a while ago,

“ The definitive report on our long-term budget gap implicitly assumes that we do nothing about that budget gap — that we keep cutting taxes and blocking spending cuts at every opportunity.”

Or, in other words, it assumes that Republicans win every fight over taxes and Democrats win every fight over spending.

Things weren’t always this way. For example, the immaculate assumption that tax revenues will remain constant as a share of the economy—despite, for example, real bracket creep, which moves people into higher tax brackets as their inflation-adjusted incomes rise—was only introduced in the past few years: as recently as 2009, the alternative scenario did not assume these mysterious tax cuts. (See this earlier blog post for an explanation.)

I didn’t realize until reading Klein’s blog post that the CBO changed its spending assumption just last year. In 2011, this is how it projected spending other than on Social Security and health care: “Beyond 2021, other spending stays at the same share of GDP projected for 2021 . . .” And this is how it changed in 2012: “For projections beyond 2022, CBO assumed that such spending would, during a five-year transition period, gradually return to its average share of GDP during the past 20 years.” The net difference from this one assumption is about 2 percent of GDP. This is a huge amount—equivalent, for example, to all of the growth in Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and health insurance subsidies over the next twenty-five years.

It’s almost as if, as Congress does things that reduce the long-term national debt (like the Budget Control Act of 2011, which may be a stupid bill, but did reduce the debt under current law), the CBO moves the goalposts further away so the problem remains the same size. This is why, in White House Burning, we adjusted the CBO’s projections, and we showed scenarios with and without the Bush tax cuts (rather than simply assuming, as most people did, that the Bush tax cuts would be made permanent for everyone).

As Klein says,

“Because everyone was used to a fake baseline that assumed their full extension, a supposedly deficit-obsessed Congress managed to resolve the so-called ‘fiscal cliff’ in January by passing a huge tax cut that added trillions to deficits while calling it, amazingly, a fiscally responsible tax increase.”

If only more people had pointed that out beforehand, maybe Congress wouldn’t have been able to get away with that one.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers