Simon Johnson's Blog, page 25

July 25, 2013

Toxic Trait To Avoid #1

By James Kwak

I generally refuse to be drawn into the Yellen-Summers horse race because (a) everything that can be said, has been said, (b) I have no original information or insight, and (c) it’s all speculation anyway. But I’m going to comment on one parenthesis in Felix Salmon’s good summary post, since it has broader application:

Summers is, to put it mildly, not good at charming those he considers to be his inferiors, but he’s surprisingly excellent at cultivating people with real power.

In my personal experience, especially in the business world, this is absolutely the worst personality trait you can find in anyone you are thinking of hiring. You see it a lot, especially in senior executives. Unfortunately, at the time of hiring, you only see the ability to manage up—not the inability to treat subordinates decently. By the time you figure it out, you’ve already suffered serious organizational damage. (Thanks to my friend Marcus Ryu for identifying this problem so clearly.)

Powerful, self-confident people—like Barack Obama—are especially vulnerable, because they tend to make decisions based on intuitive judgments, and they form those judgments based on personal impressions—exactly the thing that two-faced psychopaths are good at making. (I’m not saying that Larry Summers is necessarily a psychopath, mind you—but apparently a lot of corporate CEOs are.)

This is just another reason that it makes sense to hire people based on their objective records, not the warm fuzzy feeling you get from the job interview. Thankfully, Summers has a record to go on. Hopefully Obama will keep it in mind.

July 24, 2013

Wealth Taxes? Don’t Hold Your Breath

By James Kwak

Tyler Cowen thinks that we are entering an age of debates over wealth taxes. If only.

It’s true, as Cowen notes, that national debt everywhere is a relatively small fraction of national wealth and that, therefore, “fiscal problems are best regarded as problems of dysfunctional governance.” One of our central arguments in White House Burning was that the United States obviously, easily has the ability to pay down the national debt, and how it will do so is basically a distributional issue.

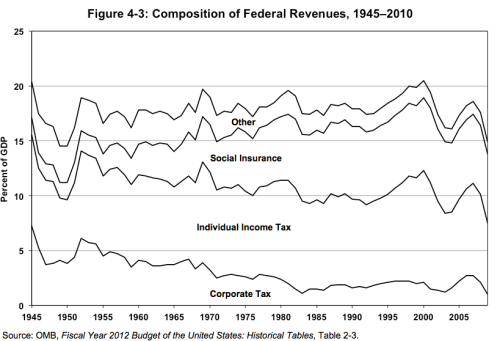

Even if wealth taxes make sense, that doesn’t mean they will happen. Cowen claims that “Like the bank robber Willie Sutton, revenue-hungry governments go ‘where the money is.’” But all that is cleverly phrased is not true. Consider this chart from White House Burning:

Since the beginning of the current round of perceived deficit problems in the late 1970s, tax revenues have shifted away from income taxes (especially the corporate income tax) and toward payroll taxes—at a time when real wages have been falling. This trend was accentuated by the 1997 (Clinton-Gingrich) and 2003 (Bush) tax cuts, which reduced capital gains taxes first to 20 percent and then to 15 percent. As capital gains have made up a larger and larger share of income, we have been taxing them less and less, with only a partial correction this year. Our one significant wealth tax—the estate tax—was slashed by Bush; even after the latest tax compromise, the exemption is set at $5 million and indexed for inflation, as compared to $1 million (unindexed) only twelve years ago.

The reasons are obvious. As much as conservatives like to portray the federal government as some kind of Leviathan out to maximize its own size at the expense of the people, the reality is that for decades people who want to cut taxes have either held the reins of power or been able to veto policies they oppose. Since they are backed by the wealthy, of course they have set about reducing taxes on wealth at every opportunity. How is that going to change—when conservatives have more than a 2-to-1 advantage in outside spending (7-to-1 for groups that don’t disclose their donors)?

July 22, 2013

Yes, We Should Worry About Public Pensions

By James Kwak

In the wake of the Detroit bankruptcy, Paul Krugman has a post pooh-poohing concerns about public pensions. His conclusion:

“Nationwide, governments are underfunding their pensions by around 3 percent of $850 billion, or around $25 billion a year.

A $25 billion shortfall in a $16 trillion economy. We’re doomed!”

(Yes, that’s sarcasm.)

I know why Krugman wants to argue that this isn’t a problem. If everyone believes that public pensions are a big problem, then the austerity crew will convert that belief into a push to cut public pensions—just like they have tried to use future shortfalls in the Social Security and Medicare trust funds to insist on privatizing or voucherizing those programs.

But for people who care about retirement security for middle-class Americans—and, more importantly, middle-class Americans who depend on public pensions—public pension shortfalls are a real problem. The public sector is the last major refuge of defined benefit pensions—the kind that provide a guaranteed annual income after retirement—and public employees paid for those pensions with lower wages while working. Shortfalls today mean a higher likelihood that those people will get stiffed when they retire, or at some point after they retire.

How big is the shortfall? Krugman focuses on the annual under-funding amount, which makes sense conceptually. In theory, if governments chipped in an extra $25 billion, then eventually the shortfalls would be made up. (All numbers are from the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.) But this rests on a huge assumption: that pension plan assets will generate investment returns of 8 percent per year.

Using an 8 percent discount rate is like taking out a second mortgage and investing the proceeds in the stock market. You may think you’re making money, but the higher expected return of the market is entirely due to the fact that you’re taking on more risk. Pension benefit payments, like mortgage payments, are essentially fixed, so they should be discounted at the risk-free rate, not the expected rate of return of pension plan investments. Simply reducing the discount rate of future pension liabilities from 8 percent to 5 percent (still well above the risk-free rate even for thirty years) reduces the funding ratio (current assets divided by the assets necessary to pay future benefits) from 73 percent to 50 percent, which makes the annual shortfall bigger.*

Not setting aside enough for pensions is a serious problem for the millions of people who are relying on those pensions. It’s not a huge problem in the grand scheme of things, but it’s not insignificant, either. Krugman understandably doesn’t want people fastening on pension shortfalls as an argument for cutting benefits or raiding other government programs (like schools). I agree. And balanced budget rules make it difficult or impossible for states to issue debt to meet their pension obligations. So there are no easy solutions. The best (leaving aside federal aid) is probably to increase state taxes—which are modestly progressive, at least in states with an income tax—to make up the gap. But it’s still a problem we need to face.

* The shortfall is based on an “annual required contribution” that includes both new liabilities and an amount required to amortize the current shortfall.

July 14, 2013

Remember Citigroup

By Simon Johnson

On Thursday of last week, four senators unveiled the 21st Century Glass-Steagall Act. The pushback from people representing the megabanks was immediate but also completely lame – the weakness of their arguments against the proposed legislation is a major reason to think that this reform idea will ultimately prevail.

The strangest argument against the Act is that it would not have prevented the financial crisis of 2007-08. This completely ignores the central role played by Citigroup.

It is always a mistake to suggest there is any panacea that would prevent crises – either in the past or in the future. And none of the senators – Maria Cantwell of Washington, Angus King of Maine, John McCain of Arizona, and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts – proposing the legislation have made such an argument. But banking crises can be more or less severe, depending on the nature of the firms that become most troubled, including their size relative to the financial system and relative to the economy, the extent to which they provide critical functions, and how far the damage would spread around the world if they were to fall.

Executives at the helm of Citigroup argued long and hard, over decades, for the ability to expand the scope of their business – breaking down the barriers between conventional commercial banking and all of forms of financial transactions, including the most risky. In effect, the decline of the restrictions established by the original Glass-Steagall – at first gradual but ultimately dramatic – allowed Citigroup to increase the scale and complexity of gambles that it could take backed by deposits and ultimately backed by the government.

At its peak in 2008, Citigroup’s assets were around $2.5 trillion (under US GAAP accounting, which gives a relatively low estimate for derivatives’ exposure) – we can call that over 15 percent of GDP. It was the largest bank in the US and arguably the largest bank in the world. A large part of its business was – and remains – outside the US but there is no doubt that policymakers, here and abroad, felt that the US government was responsible for the havoc that the failure of Citigroup could wreak.

Citigroup had been in trouble before, for example on the back of loans to emerging markets made during the 1970s and that went bad in 1982. But Citigroup was much smaller in the early 1980s – no more than a few percent of GDP – than it was in 2007. And the scope of its activities was much more limited. By the early 2000s, Citi had also become much more complex, with a presence throughout the financial system. And the opaqueness of derivatives meant that it was very hard for anyone – including the very smart people who run the Federal Reserve – to know how Citigroup’s losses could spread throughout the system.

Accounts of the financial crisis agree that the potential failure of Citigroup was viewed by policymakers as a major potential calamity to be avoided. As a result, a huge amount of official support was provided, directly and indirectly to keep Citigroup afloat. (For details, see Sheila Bair’s book, Bull by the Horns.)

Looking backwards, you could think of the 21st Century Glass-Steagall Act as a measure to unwind the structure that Citigroup would become.

But this would be to miss the point of the legislation – and why this is now an urgent public policy priority. As a result of the crisis and the bailout measures put in place by both the Bush and Obama administrations, we have five groups of firms (with a holding company at the core) that resemble Citi in the run-up to 2007: JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Citigroup itself. (And there are several other contenders for this status.)

All five of the firms contain some mix of boring traditional commercial banking, backed by insured deposits, and high risk activities – such as are inherent in investment banking and dealing in securities.

All of them are now undoubtedly too big to fail. And this creates exactly the kind of perverse incentives that prevailed at Citigroup – excessive and mismanaged risk-taking mean a few people get the upside when things go well, while the taxpayer and the broader economy gets a crazy amount of downside risk.

Even Sandy Weil, former CEO of Citigroup who led the charge against the remnants of Glass-Steagall in the 1990s, concedes that this was a regrettable mistake – and argues for all of the biggest banks to be broken up.

Meanwhile, JP Morgan Chase is bigger today than Citigroup was at its largest. And executives at the biggest banks repeatedly demonstrate their willingness to use all the economic and political means at their disposal to bulk up even further.

The point of the New Glass-Steagall Act is to complement other measures in place or under consideration, including much higher capital requirements (both in the Brown-Vitter proposed legislation and in the new regulatory cap on leverage now under consideration), the Volcker Rule, and efforts to bring greater transparency to derivatives.

These measures are not substitutes for each other – they are complements. Each would be more effective if the others are also implemented properly.

Nothing can completely remove the risk of future financial crisis. Anyone who promises this is offering up illusions and deception.

But, like it or not, public policy shapes incentives in the financial system. We can have a safer financial system that works better for the broader economy – as we had after the reforms of the 1930s. Or we can have a system in which a few relatively large firms are encouraged to follow the model of Citigroup and to become ever more careless and on a grander scale.

July 8, 2013

The Costs of “Good” Economics

By James Kwak

If there is a central argument to 13 Bankers, it is that politics matters. The financial crisis was the result of a long-term transformation of the financial sector and its place in the overall economy, and that transformation occurred because of—and contributed to—a shift in the political balance of power.

Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, authors of Why Nations Fail, take up this theme on a much broader scale in their recent article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, “Economics Versus Politics: Pitfalls of Policy Advice,” burnishing their reputations as two of the most subversive thinkers around. People have always known that economics and politics are related: that economic power produces political power and that political institutions constrain economic policy choices. Still, however, at least for the past several decades, the universal assumption has been that good economic policy is always good policy, full stop: for example, that it is always good to eliminate market failures.

This is what Acemoglu and Robinson contest. For example, assuming for the sake of argument that unions create economic distortions, unions also engage in politics on behalf of workers and, in some cases, lower-class people more generally. Policies that weaken unions not only reduce this economic distortion, but weaken the political power of the working class—which was already outgunned by capital to begin with. Given the role of unions in supporting participatory political institutions, this can be bad for democracy and for economic growth in the long run.

One specific consequence of weaker unions is that “income will typically be redistributed from workers to the managers and owners of firms.” This is often rationalized on the grounds that the “owners” of firms include, to some measure, workers themselves (primarily through their retirement account investments). But small investors have nowhere near the political organization and impact of unions (especially since their investments are largely funneled through mutual funds, whose executives do not share their political preferences).

Acemoglu and Robinson back up this conceptual insight with their usual impressive array of historical examples from around the globe. For example, the more economically efficient organization of mining contributed to autocracy in Sierra Leone, while the less efficient organization contributed to democracy in Australia. Privatization of state firms in Russia—which virtually every economist at the time supported—resulted in a concentration of wealth that was widely perceived as illegitimate and helped make possible the Putin regime. Financial deregulation in the United States is another of their examples. Some of the constraints on banks established in the 1930s and 1950s probably made little economic sense, such as restrictions on interstate banking. But the elimination of those constraints helped create larger, more politically powerful banks, which contributed to the deregulatory wave whose consequences we know all too well.

This all seems obvious. So why is it subversive? For some time now, progressives have been arguing that “free market” economic policies are bad because they ignore market failures, and therefore government policy should eliminate focus on eliminating market failures—it’s just good economics. That’s all well and good. But Acemoglu and Robinson make a significantly stronger case against pure economism. Even “good” economics can be bad for society, when the political dimension is taken into consideration.

One implication is that traditional cost-benefit analysis is incomplete: it’s not just economic costs and benefits that matter, but political ones as well. More broadly, it means that progressives—or anyone who opposes the tendency to reduce all public policy to economic factors—shouldn’t fight every battle on the terrain of economic efficiency. Of course, evaluating the impact of policy on the political landscape is both difficult and contentious. But that doesn’t make it any less relevant.

July 5, 2013

CEO Salary Justification Season Is Open

By James Kwak

Proxy season is over. Then comes the annual compilation of executive compensation data. Equilar and the Times, for example, reported that the compensation of the median CEO at a large public company was more than $15 million in 2012.

This means that now we are into the season of justifying these stratospheric numbers—and particularly the high rate of growth of those numbers. (2012 median compensation was 16 percent higher than in 2012.) For example, there was Steven Kaplan’s unconvincing attempt to justify high CEO pay by comparing it to . . . high pay among the top 0.1% (see Brad DeLong for a summary).

This ground has been trodden over a million times, and there’s little new that anyone can say about the issue. The common defense of high CEO pay is that it’s a justifiable investment given the market for talent. This is how Robert Shiller put it in Finance and the Good Society (p. 22):

“So it is plausible in turn that the board of Corporation B would offer a really attractive package to lure the CEO—a package that might, say, offer options on the company’s stock potentially worth $30–50 million if he is successful. That amount is not enormous relative to the earnings of a large company. A diligent board . . . might consider a highly qualified, proven CEO worth all of this.”

Let’s pause for a moment to note that “$30–50 million if he is successful” is actually a pretty miserly compensation package by today’s standards. The 2012 median compensation of $15 million reflects the current value of stock and option grants, not their value “if he is successful,” which is much higher. And $15 million is the median annual compensation, not the total for the CEO’s tenure.

Moreover, the standard argument that the market forces you to pay people what they are worth to your company is simply wrong. A very good developer can be worth millions of dollars a year to a software company. But she can’t command that much in salary because there are plenty of almost-just-as-good developers (and probably some just-as-good developers) who will work for, say, $150,000 per year. When you buy anything, you compare its value to that of the next best available alternative. Or, at least, that’s what you’re supposed to do.

How does this work for CEOs? Let’s assume for the moment that there is some potential CEO who, on an expected basis, can make the company worth $100 million more than it is worth under the current CEO. Should you be willing to pay her up to $99 million to work for you? No—because there are probably lots of other people out there who can also make the company worth $100 million more, or at least some large fraction thereof. It’s not the $100 million that matters—it’s $100 million minus the value of the next best available alternative.

Now, you might think that only one person in the whole world—let’s call him Ron Johnson—can increase the value of your company by $100 million, and no one else can come close. But unless Ron already has some deep connection to your company (e.g., Steve Jobs returning to Apple—and even in that case, his success was hard to foresee), you are almost certainly wrong. The marginal impact of a CEO is extremely hard to estimate in advance, and any expected value you come up with will be swamped by the standard deviation. The only honest answer is to say that there are a bunch of people who could probably help your company a lot, and that implies that you should hire the one who will do the job for the least money.

Instead, however, the directors manage to convince themselves that Ron is the only person who can save their company, and saving the company is worth $100 million, so he should get $99 million. They do this by making all sorts of basic errors of thinking, like converting their vague, irrational intuitions into certainties. Then they justify a specific transaction—overpaying Ron—by referring to a conceptual possibility.

Sure, CEOs are important, and some are highly valuable to their companies. But we’re not talking about LeBron James or Leo Messi here—there are a lot of people who can do the same job roughly as well as each other. There’s no reason the rules of ordinary labor markets should be suspended for them.

July 4, 2013

What Does 9.5% Mean?

By James Kwak

This week, the Federal Reserve approved its final rule setting capital requirements for banks. The rule effectively requires common equity Tier 1 capital of 7 percent of assets (including the “capital conservation buffer”), with a surcharge for systemically important financial institutions that can be as high as 2.5 percent, for a total of 9.5 percent. That sounds like a lot, right?

If it sounds like a lot to you, it’s probably because (a) it’s higher than capital requirements before the financial crisis and (b) the banking lobby has been saying it’s a lot to anyone who will listen. But apart from some people thinking that higher is better and others thinking that lower is better, you rarely get any basis for understanding what the numbers mean.

In school, you learn that a 9.5 percent capital ratio means that a bank can sustain a 9.5 percent fall in the value of its assets before it becomes insolvent. But that’s clearly not true, for multiple reasons. First, if a bank were to report that its capital fell from 9.5 percent of assets to 2 percent of assets, it would fail the next day as all of its short-term creditors pulled out their money in (justifiable) panic. In other words, it’s not clear how much of that capital buffer is really a buffer.

Second, that’s 9.5 percent of risk-weighted assets. We all know what risk-weighting means in theory, but few people have a firm grasp on what it means for the actual numbers. As of September 2012, for example, Goldman Sachs had $949 billion in balance sheet assets, but only about $436 billion in risk-weighted assets—although that would increase to $728 billion under new risk-weighting rules. As an illustration, if risk-weighted assets are only half of actual assets, then a 5 percent drop in asset values would be enough to wipe out a 9.5 percent capital buffer.

Third, and most important, there’s measurement error. As many have noted before, Lehman Brothers had something like 11 percent Tier 1 capital two weeks before it went bankrupt. What this means is that, as Steve Randy Waldman said and as I discussed in an earlier post, “Bank capital cannot be measured.”

Given systemically important financial institutions and imperfect regulations, capital requirements have an important role to play. But we should be setting them with the understanding that banks fail before they run out of capital, capital is difficult to measure, and the errors all come out the same way—in the banks’ favor. In practice, of course, it’s all politics: even if Daniel Tarullo wants higher capital requirements, there’s a limit to what he can get through the Board of Governors, and there’s a limit to what Ben Bernanke thinks he can get while remaining an independent agency. That’s the bottom line to remember—not that our new capital requirements are the outcome of some reasoned discussion about how much capital banks really need to protect the rest of us from their misadventures.

June 27, 2013

Save If Failure Impending

By James Kwak

Yesterday the House Financial Services Committee held a hearing on the too big to fail problem. Ordinarily a hearing includes a couple of witnesses chosen by the majority who say one thing and one or two witnesses chosen by the minority who say exactly the opposite thing. In this, however, it was hard to tell who was chosen by which side (although I can guess), given the extent of the agreement among former Fed bank president Thomas Hoenig, current Fed bank presidents Richard Fisher and Jeffrey Lacker, and former FDIC chair Sheila Bair.

All agreed that the too big to fail problem still exists, five years after the financial crisis, and that it continues to distort the market for financial services. For example, Lacker, who is perhaps the most sanguine about Dodd-Frank (he likes the living will provisions of Title I), said, “Given widespread expectations of support for financially distressed institutions in orderly liquidations, regulators will likely feel forced to provide support simply to avoid the turbulence of disappointing expectations. We appear to have replicated the two mutually reinforcing expectations that define ‘too big to fail.’”

There was disagreement over whether Dodd-Frank, and the Orderly Liquidation Authority regime that it created, would continue the practice of bailing out failing financial institutions, with Bair arguing that Dodd-Frank “abolished” bailouts. Of course, everyone is against bailouts, but at the same time everyone is in favor of protecting the financial system and the economy against disaster.

The issue comes down to what I think is a simple ambiguity about the meaning of “bailout.” In the short term, when a megabank is about to collapse, bailout can mean two different things. First, it can mean that creditors and counterparties are made whole to the extent necessary to protect the financial system from domino or contagion effects. Second, it can mean that executives keep their jobs and shareholders continue to hold an equity stake. (These could be divided into two different things, but it doesn’t matter here.) Everyone agrees that Dodd-Frank gives the FDIC, using money borrowed from Treasury if necessary, the power to do the first kind of bailout. The statute says that the FDIC can’t do the second, and that’s what Dodd and Frank pointed to when they said that their bill abolished bailouts.

When push comes to shove in the heat of the moment, it’s the creditors and counterparties that matter, though, and they will be made whole—at least to the extent necessary to protect the financial system. At a moment of great panic and uncertainty, that probably means one hundred cents on the dollar. And that is what really skews the incentives ex ante—not whether managers and shareholders will be bailed out.* As Fisher said, this is why SIFI (systemically important financial institution) really stands for “Save If Failure Impending.”

Bair realizes this, and one of her key recommendations is requiring large banks to have a thick layer of unsecured, long-term debt, so that the FDIC can impose losses on those long-term debt holders. These creditors couldn’t pull their cash out overnight in a crisis, which would give banks a more stable funding structure. I’m not confident this will work, though. As long as banks have any significant amount of short-term debt, creditors will behave as if that debt enjoys a government guarantee, and the FDIC would have to bail them out.

Lacker thinks that the system should have no government guarantees at all—which means that if a crisis erupts, the government commits to sitting by and letting the world end. He thinks we can get there via living wills, which will enable regulators to ensure that banks can be allowed to fail without causing damage to the financial system. We can get there, he argues, because regulators can reject a bank’s living will until they are confident it could be allowed to fail, ordering it to restrict its activities if necessary. But this brings us back to the question of whether regulators can and will make these complex, politically fraught decisions without being duped by bankers.

As before, I still think that simple, structural limits—making banks “too small to save,” again using Fisher’s term—are the best way to go. Hoenig recommended restricting banks to banking, securities underwriting, and asset management. Fisher recommended restricting the megabanks to “an appropriate size, complexity, and geographic footprint.” I’m tired of people like Lacker saying, “I am open to the notion that such restrictions may ultimately be necessary to achieve a more stable financial system.” They’ve had five years to try it their way, and everyone agrees TBTF is alive and well.

* As I mentioned in a previous post, Joshua Mitts has a paper arguing that this dynamic will lead managers to try to position their firms to be bailed out for precisely this reason.

June 21, 2013

Want To Reduce the National Debt? Find More Workers

By James Kwak

Why do some people oppose immigration reform? One conservative objection is that we should follow rules and punish lawbreakers (not to mention all the other arguments that have to do with protecting a white, Protestant, English-speaking nation). That fits nicely with the Strict Father worldview identified by George Lakoff. Another common conservative objection is that we can’t afford more immigration because it would increase deficits and the national debt; that also fits with the tough-minded, austerity-loving ethos of modern conservatism. The little problem is that more immigrants, and more legal immigrants, are unambiguously good for the economy and for the federal budget deficit.

This is the conclusion of two reports put out by the Congressional Budget Office this week: one a cost estimate of the bill currently in the Senate, the other an expanded estimate incorporating additional economic impacts of the bill. The bottom line is that the bill would make the economy 5.4 percent bigger in 2033 than it would be otherwise; per capita GNP would be 0.2 percent higher and wages would be 0.5 percent higher in 2033. Finally, immigration reform would reduce aggregate deficits by about $200 billion* over the first decade and about $1 trillion in the second decade.

A lot of this is simply obvious. More immigrants mean more workers mean more economic output. Legalizing undocumented immigrants means higher tax revenues from existing output. Some is slightly less obvious. Relaxing caps on immigration means more skilled workers, leading to technological innovation and higher productivity (hence higher average wages).

But what about the costs? Conservative Republicans have been painting the picture of people who come to the United States simply to live off of government programs without contributing tax revenues to fund those programs. In fact,the CBO went ahead and did a cost estimate for the second decade specifically because Republicans were arguing that the true costs wouldn’t show up until then, once immigrants qualified for benefits.

But that’s not how our current social insurance programs work. The two major programs, Social Security and Medicare, require ten years of qualifying work, with accompanying payroll tax contributions.** So for the most part, you can’t qualify for benefits without paying into the system for some period of time.

More importantly, most people immigrating to the United States are working age (or their children: they come here looking for jobs. (And if they are already retired, they won’t qualify for Social Security or Medicare.) From the standpoint of our social insurance programs, this is what we want. For example, I am paying into Social Security, but my father is benefiting from it; that’s how it works in a pay-as-you-go system. But new immigrants represent a one-time bonus: they pay in for decades before anyone in their family benefits. For the more than forty years that my immigrant father worked, he paid payroll taxes, while his parents were not collecting benefits.

Once the immigrants retire and start collecting benefits, their families become nor better and nor worse, from a fiscal standpoint, than all the families that were here already. But social insurance programs never have to pay back the net benefit they gain from that first immigrant generation. It’s free money.

More immigration is not just what our society and our economy need. It’s what the federal government’s balance sheet needs. If people want to oppose immigration reform because they don’t want to sanction past rule-breaking, that’s up to them. But they can’t oppose it on fiscal grounds.

* This amount could be reduced by $22 billion in discretionary spending required by the bill. However, under current law that discretionary spending would have to be offset someplace else because of the spending caps set by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (the debt ceiling compromise).

** The number is less for disability insurance,but in any case is not zero.

June 20, 2013

New Research in Financial Regulation

By James Kwak

Not surprisingly, there is a great deal of interesting research being done in the area of financial institutions, systemic risk, and regulatory reform. Last week I had the pleasure of attending a workshop for junior law professors held by the Insurance Law Center of the UConn Law School, where I am a professor. The workshop featured a long list of provocative and weighty papers at various stages of completion. Here I just want to point out a few that are fully drafted and available on SSRN.

Robert Weber presented what should be the canonical paper on stress testing as applied to financial institutions, which has been going on for a while but became front-page news in 2009, during the financial crisis. He traces the history of stress testing back to its engineering roots in Renaissance Italy with, perhaps unsurprisingly, Leonardo da Vinci. Weber is critical of box-checking stress testing, but argues that stress testing can be useful as a way of encouraging or inducing bank executives and risk managers to more closely investigate their assumptions and beliefs and ultimately create a “morality of quantitative skepticism.”

Gallons of ink have been spilled over the Orderly Resolution Authority established in Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act, generally over whether and how it would be used in a crisis. In 13 Bankers, Simon and I expressed skepticism that it would be used, for practical and political reasons. Joshua Mitts’s paper takes the novel approach of looking at how OLA affects managerial incentives in the pre-crisis period, arguing that it encourages bank executives to design their firms in such a way as to maximize the chance of a taxpayer bailout. This would lead them to increase their exposure to other large financial institutions and to increase the correlation of their asset portfolios with those of other large firms.

Mehrsa Baradaran takes a historical view in her paper, which is about the social contract between banks and society as expressed through banking regulation. She begins with the Hamilton-Jefferson debates over banks (which is also where we began 13 Bankers) and covers the history of banking regulation (or non-regulation) up to the 1930s, which represented the most thorough codification of the social contract: the government needs banks, but banks also need the government. The past few decades, however, have seen an erosion of this social contract, giving banks the benefits of government sponsorship and support without the obligations necessary to ensure that they serve societal ends. Baradaran argues that banking regulation should incorporate a robust public benefit test to ensure that banks are in fact helping households, the economy, and society at large.

There are other interesting papers that are sure to come out of this workshop. One small side benefit of the financial crisis has certainly been the increased attention to the financial sector and the risks it presents to the rest of us.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers