Simon Johnson's Blog, page 21

February 25, 2014

Rich People Save; Poor People Don’t

By James Kwak

It seems obvious. Yet it’s often lost, both by the scolds who lecture Americans for not saving enough and by the self-appointed personal finance gurus who claim that anyone can become rich simply ye saving more (and following their dodgy investment advice). Saving is sometimes seen as some kind of moral virtue, but from another perspective it’s just the ultimate consumption good: saving now buys you a sense of security, insurance against misfortune, and free time in the future, which are all things that ordinary people don’t have enough of.

Real Time Economics (WSJ) links to a new survey being pushed by America Saves (which appears to be a marketing campaign run by the Consumer Federation of America, which seems not to be evil*). According to the survey, there are significant differences in savings rates and accumulated savings between lower-middle- and middle-income households. And that’s treating all households in the same income bracket as being alike, leaving aside differences in family structure, cost of living, etc.

I’m all for living within your means and saving for retirement and all that. But it’s a myth to say, as America Saves does on its home page, “Once you start saving, it gets easier and easier and before you know it, you’re on your way to making your dreams a reality.” The underlying problems are stagnant real incomes for most people, rising costs (in real terms) for education and health care, increasing financial risk due to the withdrawal of the safety net, and increased longevity (good in some ways, but bad if incomes aren’t rising and you want to retire at 65). That’s why households are showing up at age 64 with less in retirement savings than they had just last decade. And why, if you feel like you’re not saving enough, it’s probably not your fault.

* But America Saves itself is supported by a bunch of financial institutions and trade associations like the Investment Company Institute, which have a vested interest in getting people to entrust more money to them.

February 24, 2014

Résumé Put Hall of Fame

By James Kwak

Before 2006, people used to talk about the Greenspan put: the idea that, should the going get rough in the markets, Chairman Al would bail everybody out. But there’s something even better than having the Federal Reserve watching your back. It’s the résumé put.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Vikram Pandit, former CEO of Citigroup, is starting a new firm called TGG which will . . . well, it’s not entirely clear. In one email, they claim “a novel approach to address the challenges that large complex organizations face in compliance, fraud, corruption, and culture and reputation.” (That’s the standard marketing tactic of describing what benefits you will provide without mentioning what you actually do.) Now, Pandit certainly has experience in a large, complex organization with compliance, fraud, corruption, culture, and reputation problems. Citigroup checks pretty much every box. But is it experience you would want to pay for?

Pandit hardly covered himself in glory as CEO of Citigroup. Basically, he took over a bank that was already heading into an iceberg, rammed it head-on into the iceberg, and then called in the Coast Guard to rescue him. He doesn’t deserve all the blame for the fact that Citi was the shakiest of the big four commercial banks in 2008, but he certainly doesn’t deserve the credit for keeping it afloat: that goes to one Timothy Geithner.

Pandit got into Citi when the bank bought the hedge fund he co-founded, Old Lane, for $800 million. Old Lane earned 3 percent in 2007, lost money in 2008, and was shut down that very summer. Hardly a performance that would merit a CEO position, but there it is. Pandit did have a successful career at Morgan Stanley before starting Old Lane, but that just seems like more evidence for the theory that working at Morgan Stanley (or Goldman Sachs) makes you seem smarter than you actually are.

So why would anyone hire Pandit to do anything—let alone “use insights into human behavior, economics and so-called big data . . . to help large, complex companies analyze employee behavior, management decision-making, business models and strategy”? (Presumably, having made something like $160 million on the sale of Old Lane, he isn’t going to work for peanuts.) To be clear, no one has hired him yet. But in general, if you become CEO of a big company, you’re pretty much guaranteed lucrative employment for as long as you want it, regardless of your performance. This is the résumé put: you have downside protection because you can always go and get another job.

The other big question is why Steven Levitt and Daniel Kahneman would want to have anything to do with Pandit. It probably isn’t the money—Levitt must be worth a gazillion dollars with the Freakonomics franchise, and I doubt Kahneman is hurting. And if they really want to bring behavioral economics and instrumental variables to big corporations, they don’t need a mediocre washout as CEO of America’s laughingstock bank.

At the end of the day, it all probably comes down to our culture’s fascination with money. Make enough of it, and people will always assume you must have deserved it one way or another. And you will always get another shot (see Spears, Britney).

February 21, 2014

$100M for Eric Schmidt?

By James Kwak

Over on Twitter, Matt O’Brien wrote:

“Why are people mad at Wall Street, & not Silicon Valley, pay?” is a piece that doesn’t include the word “bailout” http://t.co/kqmWH276Gi

— Matt O’Brien (@ObsoleteDogma) February 19, 2014

That inspired me to take a look at the article O’Brien referred to: a column by Steven Davidoff asking why JPMorgan gets pilloried for giving CEO Jamie Dimon $20 million while Google can give Chairman Eric Schmidt $106 million without incurring the wrath of the public.

I went into it thinking I would agree with O’Brien—that there is something worse about lavish Wall Street pay packages than lavish Silicon Valley pay packages. Part of that was home team bias: I spent most of my business career working for companies based in Mountain View, Sunnyvale, Menlo Park, San Mateo, and Foster City (that’s two companies and five office moves). But I ended up mainly agreeing with Davidoff.

I think O’Brien is right on the narrow question of why people are mad: JPMorgan has done a lot of bad things in recent years, while Google’s role in the world is more ambiguous. But at the end of the day, voting the chairman of the board enough money to buy a Gulfstream 650 and an entourage of 550s is not a good use of shareholder money. And it’s shockingly tone-deaf in this age of rising inequality and cuts to food stamps. That’s the topic of my latest Atlantic column.

February 19, 2014

Random Variation

By James Kwak

As I previously wrote on this blog, one of my professors at Yale, Ian Ayres, asked his class on empirical law and economics if we could think of any issue on which we had changed our mind because of an empirical study. For most people, it’s hard. We like to think that we form our views based on evidence, but in fact we view the evidence selectively to confirm our preexisting views.

I used to believe that no one could beat the market: in other words, that anyone who did beat the market was solely the beneficiary of random variation (a winner in Burton Malkiel’s coin-tossing tournament). I no longer believe this. I’ve seen too many studies that indicate that the distribution of risk-adjusted returns cannot be explained by dumb luck alone; most of the unexplained outcomes are at the negative end of the distribution, but there are also too many at the positive end. Besides, it makes sense: the idea that markets perfectly incorporate all available information sounds too much like magic to be true.

But that doesn’t mean that everyone who beats the market is actually good at what he does, even if that person gets a $100 million annual bonus. That person would be Andy Hall, the commodities trader who stirred up controversy when he apparently earned a $100 million bonus at Citigroup—in 2008, of all years. (That was a year with huge volatility in the commodities markets.)

The latest news is that Occidental Petroleum, which bought Phibro, Hall’s trading operation, from Citigroup in 2009, is now considering jettisoning its proprietary trading activities. That isn’t to say it was a bad investment; Phibro was profitable for several years after the purchase by Occidental. At the same time, though, Hall’s hedge fund, Astenbeck Capital, has posted mediocre returns—an annualized return of 5 percent since January 2008 (about the same as the total return on the S&P 500), with a drop of 8 percent in 2013.

It’s quite possible that Andy Hall is the real deal: someone whose ex ante, risk-adjusted expected returns are better than those of the markets in which he deals. But that doesn’t mean that his performance spikes, like in 2008, aren’t largely the product of random variation. This is why it’s never a good idea to buy a free agent right after he had a huge year, whether he plays baseball or commodities.

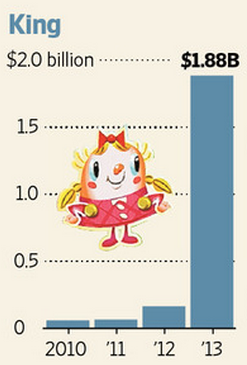

It’s also why it’s not a good idea to buy stock in a company whose revenues look like this—especially when that company has been around since 2002.

That’s not a startup that is enjoying meteoric growth: that’s a company that enjoyed some massive random variation last year. They may be better than the average mobile games company, but 2013 is not a base that they are reliably going to grow from in future years. Which means that coming up with a reasonable valuation is next to impossible.

February 18, 2014

“Telling a lie does not make you guilty of a federal crime”

By James Kwak

That’s what Jesse Litvak’s lawyer said at the start of his trial earlier today. And technically speaking, it’s true. If you’re trying to sell a bond to a client, and during the course of the conversation you say you can bench press 250 pounds when you can only bench 150, that’s not a federal crime. But if you lie about a material aspect of the bond and the client relies on your lie in buying the bond, that’s another story.

Litvak’s case is (barely) in the news because it has a financial crisis connection; some of the buy-side clients he is alleged to have defrauded were investment funds financed by the infamous Public-Private Investment Program (PPIP) set up in 2009 using TARP money, and hence one of the counts against Litvak is TARP-related fraud. But it bears on a much more widespread, and much more important feature of over-the-counter (OTC) securities markets.

Litvak was trading mortgage-backed securities for Jefferies when the alleged behavior occurred. The key feature of OTC markets is that there is no way to look up the prices at which securities are trading, as opposed to, say, on the New York Stock Exchange. If you are a buy-side investor and you want pricing information, you depend largely on the securities dealers themselves to tell you what the current prices are.

Litvak’s thing was that he lied to his clients about the prices of other transactions that he made up. For example, first Jefferies bought an MBS at $51.25. (SEC complaint, beginning on page 20.) Litvak then approached a potential buyer and claimed that a seller was offering him that bond at $55. The buyer offered $50.50. Litvak then lied three more times about the price that his phantom seller was offering: first $54, then $53.50, then finally $53, after which the buyer agreed to pay $53.25. Who would fall for this? Well, in this case it was Magnetar, the hedge fund renowned for destroying the U.S. economy (exaggeration). The complaint has dozens of similar examples, replete with ungrammatical emails detailing fictional negotiations.

The legal issues are whether Litvak violated Section 17(a) of the Securities Act or Securities Exchange Act Rule 10b-5, for which the lie has to be material and the buyer must have been harmed by it, among other things. Litvak’s defense is the usual one: his clients were sophisticated investors who could have read the documents themselves and analyzed the value of the securities independently. This might work with a jury, but it’s just wrong as an economic matter. If you’re an investor, you know that your analysis of a bond’s expected cash flows is just one opinion. What other people think the bond is worth is also valuable data—especially if you’re thinking you might want to unload the bond to another investor. If Litvak says that one investor expects to sell for $55 and only reluctantly parted with it at $53, that’s different from the fact that the investor sold it at $51.25—more than 3 percent different.

The broader issue is that this is the way OTC markets work. Dealers match buyers and sellers, or sometimes trade out of their own inventory, and everyone knows that they make money by taking a spread on each trade. But it’s impossible, or very difficult, to tell from the outside what the spread is. So even if the majority of bond dealers are upstanding model citizens, the system depends on them being upstanding model citizens—probably not what we want in a cutthroat, aggressive, money-driven culture. But the dealers want to preserve OTC markets precisely because it lets them charge large spreads, whether through deceit or not.

But why does the buy side put up with it? Partially because they don’t realize the extent to which they are being lied to. Litvak’s clients knew that he was buying low and selling high, but they had no idea how low he was buying because he lied about it. Had they known, they would have demanded lower prices or taken their business elsewhere.

But partially because everyone in this casino is playing with other people’s money, as described at length by Zero Hedge when the SEC first filed its complaint. Bond trading is a world of mutual back-scratching in which traders, who are paid a percentage of their profits, charge inflated spreads, and clients go along with it because they are paid a percentage of assets under management—and they get kickbacks in the form of gifts and entertainment from the traders. Everyone is better off except the investors at the end of the line. Which is the big reason why OTC markets are bad for ordinary people.

February 17, 2014

Not the Problem

By James Kwak

Nicholas Kristof’s ill-conceived diatribe against the supposed self-marginalization of academics has come in for a fair amount of criticism, notably from Corey Robin. The most obvious problem with Kristof’s argument assertion is that anywhere you look in the policy sphere, you can’t help stumbling over academics left and right. Macroeconomics is an obvious one, but there many others. Take education, for example, where anyone pushing for any conceivable policy change can wave a fistful of academic papers in your face.

It’s easy to multiply examples of academics doing policy work or even occupying policy positions. The bigger question, and the less obvious problem with Kristof’s opinion, is whether more of us would do any good for the world.

Consider climate change. Here, academics have hit the ball out of the park. We know the world is getting hotter, and we know why, because of hard, painstaking academic research. There are two main reasons why we’re not doing anything about it, and neither is a shortage of op-eds by professors.

The first is a well-funded campaign by fossil fuel companies and anti-government ideologues to spread misinformation. That’s just politics, given the state of American campaign finance law.

But the second is a media that refuses to call out people for simply lying about science, relying on the formula of “expert A says X and expert B says Y” instead. And a media that compounds the problem by giving prime real estate to the unqualified climate change-denying drivel of people like George Will. In other words, the journalists–Kristof’s profession–are a big part of the problem.

On most policy questions of any importance, there are enough academics doing work to generate far more policy ideas than can seriously considered by our political system. When it comes to systemic risk, we have all the ideas we need–size caps or higher capital requirements–and we have academics behind both of those. The rest is politics. What we really need is for the people with the big megaphones to be smarter about the ideas that they cover.

February 14, 2014

The Social Value of Finance

By James Kwak

It’s been more than five years since the peak of the financial crisis, and it seems clear (to me, at least) that not much has changed when it comes to the structure of the financial sector, the existence of too-big-to-fail banks, and the types of activities that they engage in. It’s also clear that the Dodd-Frank Act and its ensuing rulemakings have embodied a technocratic perspective according to which important decisions should be left to experts and made on the grounds of economic efficiency. Even the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Dodd-Frank achievement most beloved of reformers, is essentially dedicated to correcting market failures, which means attempting to achieve the outcomes that would be generated by a perfect market.

The big question is why we went down this route. The traditional explanation, and one that I’ve tended to assume in the past, is that it was a question of political power. Wall Street banks and their lawyers simply want less regulation of their industry, and they feel more comfortable granting actual rulemaking power to regulatory agencies that they feel confident they can dominate through the usual mix of congressional pressure, lobbying, and the revolving door. Given that the Obama administration also wanted to avoid structural reforms and preferred to rely on supposedly expert regulators, the outcome was foreordained.

In a recent (draft) paper, Sabeel Rahman puts forward a different, though not necessarily incompatible explanation. He draws a contrast between a managerial approach to financial regulation, which relies on supposedly depoliticized, expert regulators, and a structural approach, which imposes hard constraints on financial firms. Examples of the latter include the size caps that Simon and I argued for in 13 Bankers and the strict ban on proprietary trading that has been repeatedly watered down in what is now the Volcker Rule.

Rahman’s historical argument is that the managerial approach is actually a relatively recent creation. Among the Populists and Progressives (think of Louis Brandeis, for example), financial regulation was a political and even moral issue, and questions of the social utility of finance were paramount. In one sense, they finally won in the New Deal reforms of the 1930s. But the regulatory agencies created by those reforms became the new locus of technocratic expertise, and over time their objective became macroeconomic management rather than social progress. This trend only accelerated later in the twentieth century, bolstered by the general rise of economism and the fetishization of free markets, to the point where some (e.g., Greenspan) opposed any regulation and others defended regulation narrowly as a way of correcting for market failures.

What is missing, Rahman argues, is any actual consideration of the social value of finance in general and financial innovation in particular. In its absence, we are left with the judgment of the expert technocrats, which has predictably led us to where we are today. If we do open up the scope of financial regulation to take questions of social value into account, we might end up in a very different place.

February 13, 2014

Unequal Justice

By James Kwak

If I write about a legal matter on this blog, it usually involves battalions of attorneys on each side, months of motions, briefs, and hearings, and legal fees easily mounting into the millions of dollars. That’s how our legal system works if, say, you lie to your investors about a synthetic CDO and the SEC decides to go after you—even if it’s a civil, not a criminal matter.

But most legal matters in this country don’t operate that way, even if you face the threat of prison time (or juvenile detention), and all the collateral consequences that entails (ineligibility for public housing, student loans, and many public sector jobs, to name a few). Theoretically, the Constitution guarantees you the services of an attorney if you are accused of a felony (Gideon v. Wainwright), misdemeanor that creates the risk of jail time (Argersinger v. Hamlin), or a juvenile offense that could result in confinement (In re Gault). The problem is that this requires state and counties to pay for attorneys for poor defendants, which is just about the lowest priority for many state legislatures, especially those controlled by conservatives.

In Crisp County, Georgia, home of the Cordele Judicial Circuit, this just doesn’t happen. In 2012, for example, there were 681 juvenile delinquency and unruly behavior cases. The public defenders handled only 52 of those cases, and we know that most of the defendants couldn’t have afforded private attorneys. The result is hundreds of guilty pleas resulting in detention by children who have no idea what their rights are.

We know this because of a lawsuit (complaint; summary by Andrew Cohen) brought by the Southern Center for Human Rights. (I am a member of the SCHR’s board of directors.) This is not an isolated case. The SCHR alone has repeatedly sued the state of Georgia for underfunding its public defender system to the point where defendants lack any reasonable semblance of representation. This problem is not confined to less-serious cases (which are, of course, still extremely serious to the person facing time in prison). In Alabama, for example, state law limits the amount that can be spent on a court-appointed lawyer to $1,500—for death penalty appeals. (That’s $1,500 total, not $1,500 per hour, for those of you who work on Wall Street.)

At one end of our legal system, it’s too hard to hold anyone responsible for blowing up our financial system and costing 8 million Americans their jobs. At the other end, we are shuttling thousands of young people into detention and prison (and forcing them to pay fees for the “public defenders” who don’t show up at their hearings) because we can’t be bothered to pay decent lawyers. Something is wrong here?

February 12, 2014

Small Steps, but Not Nearly Enough

By James Kwak

Floyd Norris says some sensible things in his column from last week on the retirement savings problem: Defined benefit pensions are dying out, killed by tighter accounting rules and the stock market crashes of the 2000s. Many Americans have no retirement savings plan (other than Social Security). And the plans that they do have tend to be 401(k) plans that impose fees, market risk, and usually a whole host of other risks on participants.

But even his cautious optimism about some new policy proposals is too optimistic. One is the MyRA announced by President Obama a couple of weeks ago. This is basically a government-administered, no-fee Roth IRA that is invested in a basket of Treasury notes and bonds, effectively providing low returns at close to zero risk. The other is a proposal by Senator Tom Harkin to create privately-managed, multi-employer pension plans that employers could opt into. The multi-employer structure would reduce the risk that employees would lose their pension benefits if their employer went bankrupt.

These are steps in the right direction, but modest ones. The underlying problem with private sector defined benefit plans is that the employee takes on counterparty risk, where the employer is the counterparty. In this case, the pension plan is insulated from the risk that a company will fail, which is an improvement, but not from the risk that the plan itself will fail due to a market downturn (of the kind we have recently seen). There is language about allowing the plan to reduce benefits in such a scenario, but this of course undermines the benefit of a defined benefit pension in the first place.

The underlying problem with individual retirement savings vehicles (in addition to all the usual problems like fees, bad investment choices, leakage, etc.) is that many people just don’t make enough money to save for retirement. In this country we like to think of the ability to save as some kind of moral virtue, but in reality it’s primarily a function of your income. There is no comparison between saving 10 percent of a $250,000 annual income and 10 percent of a $15,000 annual income. What’s more, the MyRA caps out at $15,000, after which point you’re on your own in the Wild West of asset management predators firms.

MyRAs could get people in the retirement savings habit, which is useful if they start making upper-middle incomes, but not enough if they are stuck in the lower middle class. At the end of the day, the only way to ensure some degree of decent retirement income for low earners is to have a partially redistributive pension system (or a much higher minimum wage), and the only way to avoid the solvency risks of defined benefit plans is to have a federal government guarantee. (It should be no surprise that Social Security has both.) MyRAs and Harkin’s plan can help at the margins, but they won’t solve those fundamental problems.

February 11, 2014

If the Alabama Medicaid Eligibility Ceiling is $2,832 for a Family of Two . . .

By James Kwak

. . . (source), and Medicaid is more than one-third of Alabama’s budget (same source), what is Alabama doing with all the Medicaid money it gets from the federal government?

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers