Simon Johnson's Blog, page 20

March 12, 2014

It Keeps Getting Better

By James Kwak

Remember when Steve Schwarzman said that taxing carried interest was “like when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939″? Or when Lloyd Blankfein said he was doing “God’s work”? Apparently, titans of finance can’t stop themselves from giving good copy. The latest is in Max Abelson’s Bloomberg article in Bloomberg on Wall Street’s search for a Republican presidential candidate who will wave their flag: low individual taxes and a rollback of financial regulation. John Taft, U.S. CEO of RBC Wealth Management, “likened his fear for the country to ‘hiding under my desk during air-raid drills because of the Cuban missile crisis,’ when ‘literally the future of humanity hung in the balance,’” before beginning a suggestion, “If I were God.”

More seriously, the financial sector expects to be able to choose the next Republican presidential nominee. In the words of one political strategist, with Chris Christie on the rocks, ”The establishment is now looking for another favorite. . . . And by the establishment, I mean Wall Street.” At the moment, the big money is desperate enough to be looking at fringe candidates like Rand Paul, Ted Cruz, and Marco Rubio (although what they most long for is the third coming of Bush). Basically, there are huge piles of cash looking for a friendly political home, and the level of hysteria is likely to surpass what we saw in 2012. We should at least get some entertaining quotes out of it.

March 11, 2014

The Free Market’s Weak Hand

By James Kwak

“Except where market discipline is undermined by moral hazard, owing, for example, to federal guarantees of private debt, private regulation generally is far better at constraining excessive risk-taking than is government regulation.”

That was Alan Greenspan back in 2003. This is little different from another of his famous maxims, that anti-fraud regulation was unnecessary because the market would not tolerate fraudsters. It is also a key premise of the blame-the-government crowd (Wallison, Pinto, and most of the current Republican Party), which claims that the financial crisis was caused by excessive government intervention in financial markets.

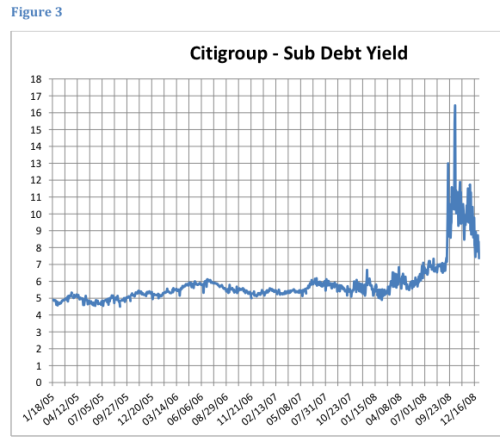

Market discipline clearly failed in the lead-up to the financial crisis. This picture, for example, shows the yield on Citigroup’s subordinate debt, which is supposed to be a channel for market discipline. (The theory is that subordinated debt investors, who suffer losses relatively early, will be especially anxious to monitor their investments.) Note that yields barely budged before 2008—despite the numerous red flags that were clearly visible in 2007 (and the other red flags that were visible in 2006, like the peaking of the housing market).

However, one thrust of post-crisis regulation has been to attempt to strengthen market discipline. This is consistent with the overall Geithner-Summers doctrine that markets generally work close to perfectly, and that regulation should mainly attempt to nudge markets in the right direction.

David Min (the lead rebutter of Wallison and Pinto’s theory of subprime mortgages, which relied on a made-up definition of “subprime”) has a new paper explaining why this is likely to fail. (The Citigroup chart is from the paper.) The remarkable thing is that market discipline not only failed to prevent banks from taking on ill-advised levels of risk, but also failed to even identify those risks until well after they were splashed all over the front page of the Wall Street Journal—like the credit rating agencies downgrading Enron mere weeks before it filed for bankruptcy.

Min identifies a couple of structural reasons for this failure—reasons that cannot be fixed simply by tweaking regulations here and there. One is that banks’ primary funding sources—whether traditional depositors or other financial institutions engaged in repo transactions—are relatively insensitive to the degree of risk in the instruments they hold. Another is that the key form of market discipline on large banks seems to be that exerted by shareholders—and shareholders like risk, especially when banks are highly leveraged (because they can shift downside risk onto creditors).

Ultimately, one of Min’s suggestions is that we simply cannot rely heavily on market discipline as a means of constraining risk-taking by financial institutions. This leaves us with relatively unfashionable tools like higher capital requirements and structural reforms (size and complexity limits). But that’s not nearly sophisticated enough for the Geithner-Summers-Bernanke crew.

March 10, 2014

Good Times for Capital

By James Kwak

Last week, the Wall Street Journal highlighted a Federal Reserve report on total household net worth. Surprise! Americans are richer than ever before, both in nominal and real terms.

At the same time, though, wealth inequality is increasing from its already Gilded Era levels. The main factor behind increasing household net worth over the past year was the rising stock market (followed far behind by rising housing prices). These obviously only help you if you own stocks—not if, say, you never had enough money to buy stocks, or you had to cash out your 401(k) in 2009 because you were laid off. Put another way, rising asset values help you if you are a supplier of capital more than a supplier of labor.

Is there anything we can do about this? The conventional wisdom from the political center all the way out to the right fringe is that we shouldn’t tinker too much with the wealth distribution—otherwise people won’t work as hard, which is bad for everyone. But perhaps it isn’t true.

In a new paper (Vox summary; hat tip Mark Thoma), three IMF economists look at the relationship between redistribution—measured by differences between the pre-tax-and-transfer income distribution and the post-tax-and-transfer income distribution—and overall economic growth over five-year periods, across countries and across time. They find (from the summary) “remarkably little evidence in the historical data used in our paper of adverse effects of fiscal redistribution on growth.” In general, that is, average levels of redistribution tend to be associated with higher levels of growth that are sustained for longer.

Why would this be? One reason is that inequality, in and of itself, seems to be associated with lower levels of growth. So if you redistribute income in order to reduce inequality, even if it is true that this hurts incentives to work hard, the reduced inequality has a countervailing (and, in most cases, stronger) effect.

Indeed, there’s a strong argument to be made that a capitalist society needs systematic redistribution to survive. Thomas Piketty’s new book—which I plan to read the next time I have time to read a 700-page economics book—free markets generally produce higher returns on capital than on labor, which means, to a first approximation, that people with capital will get richer faster than people with only labor. In a world where the political system is open to money, this means that the capitalists will also accumulate a disproportionate share of political power, leading to the type of extractive society described by Acemoglu and Robinson in Why Nations Fail. Which is not a world that most of us would want to live in.

March 7, 2014

The Fallacy of Financial Education

By James Kwak

In White House Burning, there is a section on the rise and political influence of the conservative media. At one point, I looked up the top ten talk radio shows by audience. Nine of them were unabashedly right-wing, politically oriented shows. The tenth was Dave Ramsey. Ramsey has plenty of conservative elements: religion, moralism, glorification of wealth. But his show isn’t about conservative politics. It’s about personal finance.

Ramsey is a huge success because—in addition to his charisma and marketing skills—he is peddling one of the huge but popular illusions of American culture: that people can become rich by making better financial decisions. He’s also one of the characters skewered by Helaine Olen in her recent book, Pound Foolish, which describes the fallacies, hypocrisies, and borderline-corrupt schemes of personal finance gurus like Ramsey and Suze Orman. It’s a fun read—a bit repetitive, but that’s largely because all personal finance “experts” are pushing a small handful of myths.*

The “sham” of the financial literacy movement—the idea that all of our financial problems would be solved if Americans were better educated about money—is the subject of Olen’s article in Pacific Standard. More than a dozen states require personal finance classes in high school, even though the evidence is that they have no impact. In short, people who consume financial education behave no differently from people who don’t.

There is a whole hierarchy of reasons for this. One is that people tend to forget what they learn in class—no matter what class you’re talking about. One is that at the moment of making the financial decision—say, to take out the subprime mortgage—anything they may remember from class is overwhelmed by the sales pitch of the mortgage broker sitting in front of them. One is that people make financial decisions on irrational grounds.

There are a couple of structural reasons, as well. Financial education content has to come from somewhere—and overwhelmingly it comes from the asset management industry itself, which has the incentive to teach people many of the wrong things. Financial education courses are often designed by financial institutions themselves; financial “education” available on the Internet is even more likely to be a type of marketing above all else.

Beyond that, it’s not even clear—to me, at least—that there is a scientific basis of agreement on how people should make financial decisions. Sure, there are some obvious things that any informed expert should know: buy index funds (for liquid, near-efficient markets) and minimize fees, for example. But when it comes to asset allocation, for example, there are reputable people like Ian Ayres who say that young people should invest more than 100% of their assets in the stock market, and reputable people like Zvi Bodie who say that the minimum amount of money you need for retirement should be invested in inflation-indexed Treasuries. Similarly, you could get a spectrum of reasonable opinions on the wisdom of taking out loans to go to college. (Up to a point, most of the opinion would be in favor because of the expected earnings boost you get from education, but it depends on a lot of factors like where you go to college, what you study, etc.).

Olen’s book shows in entertaining detail that the way most financial education is done is a joke. (Ramsey, for example, advises people to pay down their debt in increasing order by principal amount—not descending order by interest rate, which is obviously better from an, um, financial perspective.) But it’s not clear to me how much of it could even be done right. The bottom line is that it’s no panacea—not for poor financial decision-making, let alone for the income inequality and threadbare safety net that are the underlying cause of most serious personal financial problems.

* I’m about a third of the way through at this point. I only read it during Tuesday morning “family reading” with my daughter at school. She sits next to me and reads historical fiction.

March 6, 2014

Posturing from Weakness

By James Kwak

President Obama’s 2015 budget proposes a number of tax increases that will mainly affect the rich. They include:

Limiting the tax savings on deductions to 28 percent of the deduction amount (and applying this limit to exclusions as well, such as the one for employer-provided health benefits)

Requiring a minimum 30% income tax on income less charitable contributions, which is intended to limit the benefit of tax preferences on capital gains and qualified dividends

Reducing the estate tax exemption from $5.34 million to $3.5 million and raising the estate tax rate from 40% to 45%

Eliminating tax preferences for retirement accounts once someone’s account balance is enough to fund a $200,000 annuity in retirement (simplifying slightly)

These are all good things, given the size of the projected national debt and the urgent needs elsewhere in society. But, of course, they have no chance of actually happening.

If President Obama really wanted these outcomes, there was a way to get them. He could have let the Bush tax cuts expire for good a year ago, making high taxes on the rich a reality. Then, a year later, he could have proposed a middle-class tax cut and dared the Republicans to block it in an election year. (He could also have traded a reduction in the top marginal rate—from the 39.6% that would have resulted, not counting the 3.8% Medicare tax—for the reforms he is now proposing.)

But no. Instead, he locked in low marginal rates, including low rates on dividends, that cannot be budged so long as Republicans have 41 votes in the Senate. And today he’s left waving a “roadmap” that has no chance of becoming reality.

March 5, 2014

“Retirement Security in an Aging Society,” or the Lack Thereof

By James Kwak

James Poterba wrote up a very useful overview of the retirement security challenge in a new NBER white paper. (I think it’s not paywalled, but I’m not sure.) He provides overviews of much of the recent research and data on life expectancies, macroeconomic implications of a changing age structure, income and assets of people at or near retirement, and shifts in types of retirement assets.

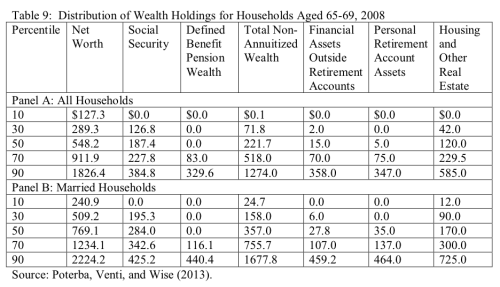

In the past, I’ve used the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances as my source for data about the inadequacy of many households’ retirement savings. Poterba has a new, perhaps even more stark snapshot:

You have to read down the columns, not across the rows. That is, the first row doesn’t give you the financial picture of the 10th-percentile household. Instead, it gives you the net worth of the 10th-percentile household by net worth, the present value of Social Security benefits for the 10th-percentile household by Social Security benefits, and so on.

Still, it’s eye-opening. It says that 50% of households have personal retirement accounts worth $5,000 or less; 50% of households have other financial assets of $15,000 or less; and 50% of households have no defined benefit pensions. 30% of households have total wealth, not counting annuitized pensions, of $72,000 or less. As of late last year, a 65-year-old woman buying a life annuity with a 3% annual escalation clause would get 3.7% of her up-front payment per year (Table 15), so $72,000 in wealth would generate just $2,664 per year—and that’s assuming she finds a way to liquidate her home equity (often the main source of wealth for people in the low-to-medium wealth tiers). And these data are from the 2008 Health and Retirement Survey, so they are only partway down from the housing market peak of late 2006.

These figures might not be so worrying if defined benefit and defined contribution plans turned out to be substitutes for each other—that is, if households without DC plans tended to have DB plans and vice versa. But that doesn’t seem to be the case. First, 26% of households headed by individuals aged 55–64 have no retirement plan at all, and 37% have only one plan (DC, DB, or IRA). Second, it turns out that the more retirement plans you have, the more you tend to have in each one; for example, people who have IRAs, DC plans, and DB plans have higher balances in their DB plans than people who have fewer plans (Table 13).

The overall picture is that the combination of income inequality and a retirement system that largely caters to high-income workers (for example, through tax preferences that disproportionately benefit people in high tax brackets who can afford large retirement contributions) has created vast inequality in retirement preparedness. Poterba does some back-of-the-envelope calculations indicating that people will most likely have to save a lot more than most people are saving today if they want to enjoy decent replacement rates in retirement.

This is true as an arithmetic point, but of course your ability to save depends more than anything else on your income. Absent some form of lifetime income risk sharing (like Social Security), it’s not clear there is a solution for people near the bottom of the income distribution.

March 4, 2014

Ukrainian Chess

By Peter Boone and Simon Johnson

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry arrived in Kiev on Tuesday. The Obama administration is feeling real pressure from across the political spectrum to “do something”, but the US has no military options and little by way of meaningful financial assistance it can offer to Ukraine. The $1 billion in loan guarantees offered today by Mr. Kerry means very little.

Millions of people have a great deal to lose if the situation gets out of control, and the Russian leadership is behaving in an unpredictable manner. The sharp drop in the Russian stock market index on Monday morning, alongside an emergency hike in interest rates by the Central Bank, demonstrates that Russia’s financial elite was also caught completely off guard.

Mr. Kerry can and has made threats, but it would be better to join the Europeans in helping to calm the situation. There is a completely reasonable and peaceful path to a solution available, but only if everyone wants to avoid a major conflict.

The alternative to peace will be ugly. Many Russians believe that the Maidan uprising will negatively the rights of ethnic Russians in Ukraine. The fact that the new authorities in Kiev quickly sought to repeal Russian as an official second language inflamed these fears (the interim president, Oleksandr Turchynov, vetoed the proposed law on Sunday). Russian President Vladimir Putin will not stand by quietly if ethnic Russians protest and such protests lead to violence. The borders of Ukraine may be redrawn, and the ensuing conflict would be painful for all involved.

Russia will pay a high cost for its unilateral intervention in Crimea. Many in western Ukraine have been further alienated, while some Russian-speaking Ukrainians and ethnic Russians in Eastern Ukraine will not like the bullying tactics. But the big Russian choice lies ahead: Putin can heed “calls” to bring his military further into Eastern Ukraine (a threat articulated in public by one of his aides in September), or he can work with the EU, the US, and all Ukrainians to seek out a more democratic outcome.

Which way this situation develops will depend on three factors.

First, Ukraine’s established politicians have spent the last two decades playing off the US and Russia, and extracting resources from both sides. Corruption among this group is pervasive; in no sense have they managed Ukraine for its people.

The genuine Ukrainian street revolution is against the political elite most closely aligned with Yanukovych. But do not get too starry eyed about new democrats already taking over – the people now holding the reins of power have been prominent before.

Second, the Russians have what they see as legitimate security concerns. They are Ukraine’s largest trading partner, they transport a lot of natural gas across Ukraine through soviet-built pipelines, and their Black Sea Fleet – based in Crimea – is seen as a major strategic asset. The Russians sell their gas cheaply to Ukraine. They have repeatedly forgiven large arrears on payments and ignored gas gone missing in transit. It is naïve to think Russian interests can now be ignored in a “winner take all” victory for the opposition.

Third, with the ouster of President Viktor Yanukovych, pro-Russian forces lost a big round. But the current pro-western forces are unlikely to remain strong and undivided. The pro-Western 2004 “Orange Revolution” rapidly collapsed with accusations of corruption and betrayal amongst partners – leading ultimately to Yanukovych’s election in 2010.

The appointment in recent days of three rich Ukrainian businessmen to the Ministry of the Interior and to key gubernatorial positions suggests the fight against corruption will be uphill.

Mr. Kerry should push for more representative government in Ukraine. There need to be elections, including for the presidency (currently scheduled for May) and for parliament. And there needs to be a negotiation – involving Europe, the U.S., and Russia, as well as Ukrainians – over how these elections will be managed so they are fair and can ensure all ethnic groups in Ukraine are represented in future government. This could involve constitutional reform, to be approved by a national referendum.

Some Europeans and Ukrainian officials are suggesting the EU association agreement (EUAA) should be signed immediately. Rapid accession prior to establishing a more representative political process would be a mistake. Implementing the EUAA demands years of legislative work that will bring Ukraine’s laws closer to Europe’s legal framework. Such long-term reforms can’t be managed or promised by a government lacking a broad mandate, and one that only recently toppled an elected President.

Mr. Kerry is not in a position to provide generous loans, and money will not be forthcoming from Europe, but large funds are not needed. The International Monetary Fund can lend the amounts needed to refinance its own debts and to build some foreign exchange reserves as a way to build confidence. Domestic bonds are largely held by domestic banks, and those can be rolled over and refinanced if the authorities work with the banks on a plan.

Most importantly, the Ukrainians should end their dependence on cheap Russian gas by agreeing to pay market prices going forward. They need to pass these prices on to local customers, effectively ending subsidies and reducing the budget deficit. Ukraine needs to stop running budget deficits that can’t be safely financed at home. For now, that means balancing the budget.

All this is not enough to create a more dynamic and prosperous Ukraine, but at least the benefits to corrupt Ukrainian politicians from playing off East and West will have been reduced, and a new representative, elected regime will be in place.

March 3, 2014

Politics: Another Way To Waste Shareholder Money

By James Kwak

I don’t often go to academic conferences. My general opinion is that at their best, sitting in a windowless room all day listening to people talk about their papers is mildly boring—even when the papers themselves are good. And it takes a lot to justify my spending a night away from my family.

Despite that, a little over a year ago I attended a conference at George Washington University on The Political Economy of Financial Regulation. I went partly because my school’s Insurance Law Center was one of the organizers, partly because there was a star-studded lineup (Staney Sporkin, Frank Partnoy, Michael Barr, Anat Admati, Robert Jenkins, Robert Frank, Joe Stiglitz (who ended up not showing), James Cox, and others, not to mention Simon), and partly because I have friends in family in DC whom I could see. It was one of the best conferences I’ve been to, both for the quality of the ideas and the relatively non-soporific nature of the proceedings.

Many of the papers and presentations from the conference are now available in an issue of the North Carolina Banking Institute Journal (not yet on their website), which should be of interest to financial regulation junkies. My own modest contribution was a paper on the issue of corporate political activity. (In a moment of unwarranted self-confidence, I told one of the organizers I could be on any of three different panels, and they put me on the panel on “political accountability, campaign finance, and regulatory reform.”)

In the wake of Citizens United (and, more to the point, SpeechNow.org), there is plenty of discussion of how campaign finance law might be changed to limit political participation by corporations. My paper takes another approach, asking whether existing corporate law already places limits on the ability of a corporation’s directors and managers to dedicate corporate resources (which, according to the commonly accepted doctrine, belong in some sense to shareholders) to political purposes. (This question was raised by John Coates, among others, who has studied whether corporations can claim to be getting economic benefits for their political contributions.) Courts so far have not placed many limits on the ability of corporations to contribute to super PACs, 501(c)(6) organizations like the Chamber of Commerce, 501(c)(4) “social welfare” organizations like Karl Rove’s Crossroads GPS or President Obama’s Priorities USA (both of which have affiliated super PACs), or 501(c)(3) charitable organizations like the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation.

I argue in my paper that courts could, at least theoretically, scrutinize political contributions as potential violations of insiders’ duty of loyalty (to the corporation and to shareholders). That is, if the CEO of a company makes a contribution in the expectation of some personal benefit (like lower individual income taxes), even if the contribution might also benefit the corporation, the courts should apply a higher standard of review.

The paper also winds its way into a discussion of corporate contributions to charities in general. Although such contributions are generally unquestioned, they rest (at least in some states) on a relatively thin and dodgy set of precedents. The line of cases begins with a Cold War case (A.P. Smith Manufacturing Co.) in which a corporate contribution to Princeton University was justified essentially as a way of protecting democracy from the communist threat. It culminates in Kahn v. Sullivan, in which the judge reluctantly signed off on a massive gift by Occidental Petroleum to build a monument to its CEO, Armand Hammer—in part because of the unusual posture of the case, in which one set of plaintiffs was contesting a settlement negotiated by a different plaintiff. The result is that today CEOs can give away (shareholder) money to “charities” (and take the attendant board seats and social status for themselves) without even having to claim that the contribution will provide a net benefit to the corporation.

At the end of the day, the importance of corporations in both realms—electoral politics and charitable giving—is probably overstated. Less than 5 percent of charitable contributions are made by contributions; all the blockbuster gifts you read about are by individuals or their private foundations. On the political side, it is a fact that super PACs were overwhelmingly financed by individuals; but because we don’t know who is contributing to (c)(4) and (c)(3) organizations, it’s possible that corporations are playing a significant role there. We just don’t know (which is one reason why we need greater disclosure of political spending, as argued by Lucian Bebchuk and others.) Regardless of the volume of corporate political spending relative to spending by Sheldon Adelson and his ilk, however, corporate insiders shouldn’t be allowed to waste shareholder money on their own pet political beliefs.

February 28, 2014

Software Is Great; Software Has Bugs

By James Kwak

I’m not qualified to comment on the internals of Bitcoin; I’m neither a programmer (OK, Alex, not much of a programmer) nor a computer scientist. But I do know that Bitcoin exists because of software that people wrote, and every means by which we use Bitcoin also operates because of software that people wrote. The problem here is the “people” part—people make mistakes under the best of circumstances, and especially when they have an economic incentive to rush out products. That’s why, while we love what software can do for us, we also like having a safety net—like, say, the human pilots who can take over a plane if its computers crash. This is the subject of my latest column over at The Atlantic. Enjoy.

February 26, 2014

The Costs of Bad 401(k) Plans

By James Kwak

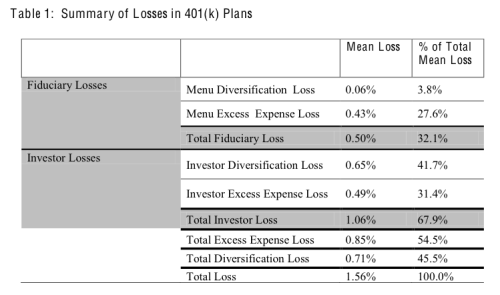

Mixed in with blogging about this, that, and the other thing, it’s nice to occasionally write on a topic I actually know something about. 401(k) plans and the law surrounding them were the subject of my first law review article (blog post). They have also been in the crosshairs of Ian Ayres (who simultaneously works on something like nineteen different topics) and Quinn Curtis, who have written two papers based on their empirical analysis of 401(k) plan investment choices. The first, which I discussed here, analyzed the losses that 401(k) plans—or, rather, their administrators and managers—impose on plan participants by inflicting high-cost mutual funds on them. The second, “Beyond Diversification: The Pervasive Problem of Excessive Fees and ‘Dominated Funds’ in 401(k) Plans,” discusses what we should do about this problem. To recap, the empirical results are eye-opening.  This table shows that 401(k) plan participants lose about 1.56 percentage points in risk-adjusted annual returns relative to the after-fee performance available from low-cost, well-diversified plans. The first line indicates that participants only lost 6 basis points because their employers failed to allow them to diversify their investments sufficiently. The big losses are in the other three categories:

This table shows that 401(k) plan participants lose about 1.56 percentage points in risk-adjusted annual returns relative to the after-fee performance available from low-cost, well-diversified plans. The first line indicates that participants only lost 6 basis points because their employers failed to allow them to diversify their investments sufficiently. The big losses are in the other three categories:

Employers forcing participants to invest in high-cost funds by not making low-cost alternatives available

Investors failing to diversify their investments, even when the plan makes it possible

Investors choosing high-cost funds when lower-cost alternatives are available

Now you could say that the latter two sources of losses are the fault of individual plan participants, but that is cutting the employers (and the plan administrators they hire) too much slack. In particular, administrators should know that, if you offer both an S&P 500 index fund and an actively managed fund that closet-indexes the S&P 500 for 120 basis points more, some people will put their money in the latter.

The conclusion that Ayres and Curtis draw, which I also drew based on a different line of argument, is that many 401(k) plan fiduciaries—roughly speaking, employers and other parties with a management role in a 401(k) plan—are not meeting their legal obligations to protect the interests of plan participants. The key legal problem is the existence of the section 404(c) safe harbor, which exempts employers from liability for losses that are due to participants’ investment decisions. As currently interpreted by most courts, the safe harbor protects employers from liability for negligently constructing menus of investment options, so long as the resulting menu meets certain criteria met by the Department of Labor—criteria that allow plans to be stuffed with high-fee, actively managed mutual funds.

Ayres and Curtis argue that, although these legal standards could be modified, relying on participant lawsuits is a haphazard and at best partial solution to the problem. Instead, they propose a new regulatory scheme in which participants are defaulted into low-cost funds and must overcome some kind of barrier in order to switch into more expensive investment choices. In addition, participants would be allowed to roll their money out of 401(k) plans that do not offer low-cost investment options. This would be a vast improvement over the current system, to the tune of billions or even tens of billions of dollars a year.

There is a host of known problems with 401(k) plans as retirement savings vehicles. Ultimately, several of those problems stem from a faulty statutory and regulatory scheme—one that is based on a statute, ERISA, which was originally designed for defined benefit rather than defined contribution plans. Unfortunately, the current system has its ardent defenders—most notably the asset management industry, which likes the ability to charge high fees to captive customers, and the protection they receive from current judicial interpretations of the statute. Ordinary workers, as always, don’t have much of a lobby.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers