Simon Johnson's Blog, page 17

May 13, 2014

What Is Social Insurance? Take Two

By James Kwak

More than a year ago I wrote a post titled “What Is Social Insurance?” about a passage in President Obama’s second inaugural address defending “the commitments we make to each other – through Medicare, and Medicaid, and Social Security.” In that post, I more or less took the mainstream progressive view: programs like Social Security are risk-spreading programs that provide insurance against common risks like disability, living too long, poor health in old age, and so on.

Since then, I undertook to write a chapter on social insurance for a forthcoming Research Handbook in the Law and Economics of Insurance, edited by Dan Schwarcz and Peter Siegelman. In writing the chapter, I decided that things were somewhat more complicated.

In brief, I still think that social insurance programs—or, rather, the programs that are generally thought of as social insurance, since there is no good definition of them out there—provide risk-spreading insurance when viewed over a long time horizon. So from a lifetime perspective, the insurance function means that most people are made better off, even though a program as a whole may be a zero-sum game in dollar terms. But in the short term, it’s pretty clear that Social Security and programs like it are largely redistributive rather than risk-spreading, because in the short term I have no chance of collecting retirement benefits and little chance of collecting disability benefits. (Given the nature of my work, there aren’t that many disabilities that would prevent me from earning more than I would make in disability benefits.)

In other words, I think a crucial feature of social insurance is that it is redistributive in the short term (in an ex ante sense, not the trivial ex post sense that is true of all insurance) but risk-spreading in the long term. I happen to think that the world would be a better place if we considered the long term and, therefore, decided to maintain these programs. But I don’t think it’s obviously true that a lifetime perspective is correct and a one-year perspective is incorrect.

In particular, if you think that Social Security won’t be around when you retire, then you would logically take a short-term perspective in which you pay taxes but never receive benefits (unless you go on disability, or you die while Social Security still exists). Then you should rationally want to eliminate Social Security as soon as possible. Conversely, if you believe that Social Security will be around when you retire, then you will evaluate the whole thing, including its insurance value, which will make you more likely to vote for it. So it’s not surprising that a major component of the anti-Social Security campaign consists of trying to convince young people (who ordinarily gain the most from insurance, since they face the most uncertainty) that Social Security cannot exist when they retire.

If you want to read more, the draft chapter is up on SSRN. Enjoy.

May 9, 2014

Finance and Democracy

By James Kwak

Roger Myerson, he of the 2007 Nobel Prize, wrote a glowing review of The Banker’s New Clothes, by Admati and Hellwig, for the Journal of Economic Perspectives a while back. Considering the reviewer, the journal, and the content of the review (which describes the book as “worthy of such global attention as Keynes’s General Theory received in 1936″), it’s about the highest endorsement you can imagine.

Myerson succinctly summarizes Admati and Hellwig’s key arguments, so if you haven’t read the book it’s a decent place to start. To recap, the central argument is that under Modigliani-Miller, the debt-to-equity ratio doesn’t affect the cost of capital and therefore doesn’t affect banks’ willingness to extend credit; the real-world factors that make Modigliani-Miller untrue (deposit insurance, taxes, etc.) rely on a transfer of value from another party that makes society no better off.

Myerson’s main point, accepting Admati and Hellwig’s position, has to do with the politics of bank regulation. Financial crises can have huge costs for society, as we know, and fundamentally they are about a failure of trust—trust that the banks are solvent, or that the bankers know what they are doing. As capital regulation has become more technical and complex, we have been increasingly asked to simply rely on the expertise of the regulators, since we cannot rely directly on the disclosures provided by the banks.

In 2008, we learned that relying on the regulators was a catastrophic error. Six years later, however, we have no better solution. Politicians, regulators, and bankers have engaged in a great deal of ritual display to try to make us believe we should trust them (resolution authority! living wills! clearinghouses! Volcker Rule! contingent convertible bonds!). But the basic nature of Dodd-Frank was more complexity, more rulemakings, more back-alley rulemaking, and less transparency. Dodd-Frank has probably helped in several ways, but it hasn’t given us any reason in general to have more confidence either in banks or in regulators. Instead, I think most people throw up their hands and move on because they have no other option.

As Myerson writes:

“With so much money in the banking system, our hope that regulators and officials will not be induced to falsely certify unsafe banks must depend on confidence that a failure of appropriate regulation could be discovered, reported in the press, and understood by voters well enough to cause a ruinous scandal for the responsible officials. . . .

“If there are abstruse financial transactions that generate risks which cannot be adequately represented in standard public accounting statements, then perhaps such transactions should be off limits for banks that are in the business of issuing reliably safe deposits.”

In other words, it’s not just that complexity can cause banks to blow up. It’s also that complexity makes it impossible for regulators to monitor banks, which is a critical ingredient in the financial crises that we all supposedly want to avoid.

Besides the primary reason for higher capital requirements—safer banks—this is the political reason for higher capital requirements (and other simple, structural fixes like smaller banks). More equity, based on standards that cannot be gamed by banks, is crucial to ensuring that the safety of the financial system does not depend on a secretive cadre of technocrats whose personal interests (whether or not they act on those interests) are decidedly aligned with those of the banks they regulate. Otherwise, as Myerson warns, “if nobody outside of the elite circles of finance can recognize a failure of appropriate regulation, then such failures should be considered inevitable.”

May 7, 2014

Tax Policy Revisionism

By James Kwak

In an otherwise unobjectionable article about The Piketty, the generally excellent David Leonhardt wrote this sentence: “In the 1950s, the top rate exceeded 90 percent. Today, it is 39.6 percent, and only because President Obama finally won a yearslong battle with Republicans in early 2013 to increase it from 35 percent.”

Is “yearslong” really a word?

But that’s not what I mean to quibble with. It’s that “yearslong battle with Republicans.”

Let’s review the facts. The 39.6 percent tax rate dates from the first Clinton budget act in 1993. It was lowered to 35 percent by the 2001 Bush tax cut, which had a sunset provision at the end of 2010 because Bush couldn’t get 60 votes to pass it, so he had to use reconciliation, which under the Byrd Rule couldn’t be used to increase the deficit more than 10 years in the future. The 35 percent rate was then extended for two years by the December 2010 tax cut, which was supported by President Obama and passed with overwhelming bipartisan support. It finally expired on January 1, 2013, at which point the 39.6 percent rate reappeared in its original form. A few hours later, Congress passed a new tax cut for just about everyone, except households with income over $450,000, who were left with the 39.6 percent rate.

In other words, President Obama didn’t fight a battle with Republicans. He fought a battle with himself. In 2010 and 2012 he could have restored the top tax rate to 39.6 percent simply by doing nothing and letting the Bush tax cuts expire. The January 2013 tax bill also locked in big tax preferences for capital gains and dividends, though not quite as big as envisioned by President Bush.

President Obama talks a good game when it comes to inequality, but he hasn’t backed it up with actions. There may have been extenuating circumstances, sure. But when it comes to tax policy, his main impact has been to make permanent most of the inequality-increasing tax cuts that his predecessor’s most treasured legacy.

May 2, 2014

The “Chicken(expletive) Club”

By James Kwak

Update: See notes in bold below.

The only “Wall Street” “executive” to go to jail for the financial crisis was Kareem Serageldin, the head of a trading desk at Credit Suisse, according to Jesse Eisinger in a recent article. Serageldin pleaded guilty to—get this—holding mortgage-backed securities at artificially high marks in order to minimize reported losses on his trading portfolio.

Now if that’s a crime, there are a lot of other people who are guilty of it. In fact, a major premise of the federal government’s crisis response strategy was exactly that: allowing banks to keep assets at inflated marks in order to pretend they were solvent when they weren’t. FASB changed its rules in April 2009 in order to make it easier for banks to inflate their marks. And the Obama administration’s “homeowner relief program” was designed to allow banks to delay realizing losses on their mortgage loans by dragging out—but generally not preventing—foreclosures. (Remember “foam the runway”?)

Combine Serageldin’s story with the story of the vigorous prosecution of Abacus Federal Savings Bank—a little Chinatown bank that, if anything, was probably allowing its borrowers to underreport their income on loan applications—which Matt Taibbi tells in the first chapter of his latest book, and the picture you get isn’t pretty. It’s a picture of the immense resources of the American criminal justice system being deployed against bit players, with no consequences for the people responsible for the financial crisis. The judge in Serageldin’s case even called his conduct “a small piece of an overall evil climate within the bank and with many other banks.”

Eisinger’s article attempts to explain why the Justice Department hasn’t even tried to convict anyone at a bank with any significant responsibility. And it’s not like they haven’t been given the opportunity. What about Standard Chartered, where manually overtyping data fields to circumvent money laundering controls was a written procedure? According to Eisinger, it’s a combination of blowback from the Arthur Andersen conviction, lack of resources, lack of practice in prosecutions, and court cases disallowing some of the DOJ’s more aggressive tactics.

There are also the usual suspects. There is the Federal Reserve protecting the banks, warning the DOJ not to go after PNC Bank because of financial stability concerns. There is the revolving door: “According to numerous former criminal-division employees, [Lanny] Breuer almost immediately signaled his interest in bigger things.”

There is the thrill of the easy victory. Exhibit A: Preet Bharara’s 80–0 record in insider trading cases. As a former Southern District prosecutor said: “They made our careers, but they don’t change the world.” [I originally wrote that Bharara himself said this, but I misinterpreted the subject of the sentence in Eisinger's article.] By contrast, Eisinger quotes James Comey, a deputy attorney general in the second Bush administration: “We have a name for prosecutors who have never lost — the ‘Chicken(expletive) Club.’”

What’s missing is any reason to think things will change. Basically, everyone is well served by the current arrangement. Prosecutors rack up impressive winning records, the revolving door spins, and the banks continue doing what they do. Even as we amass more evidence of their basic incompetence and out-of-controlness, in the form of Lehman CFO Ian Lowitt saying the bank had $42 billion of liquidity—five days before it went bankrupt. “When Lowitt came to talk to Jenner & Block,” Eisinger continues, “he explained that he had not fully understood the issues when he assured investors of its liquid assets.” Not very reassuring.

April 30, 2014

The Conspiracy Behind the B of A “Mistake”

By James Kwak

Some very clever people deep in the bowels of Bank of America’s accounting and regulatory compliance departments came up with a clever strategy to show, once and for all, that their bank is too big to manage. On Monday, the bank admitted that it had misplaced $4 billion in regulatory capital because of an error in accounting for changes in the value of its own debts. Coming less than two months after Citigroup $400 million in cold, hard cash in its Mexican subsidiary, this latest mixup is clearly part of a concerted campaign by employees of the big banks to definitively prove that their top executives have no idea what is going on.

This shadow lobbying campaign can be traced back to its origins in the LIBOR scandal (“Let’s rig the world’s largest market and see if Vikram Pandit notices.”) and the London Whale trade (“Let’s make a colossal bet on the relative values of different corporate bond indexes and see if Jamie Dimon notices.”). The only possible explanation for this seemingly never-ending stream of embarrassing disclosures is the existence of a conspiracy, orchestrated by some of the smartest bankers in the world, designed to broadcast to the world the message that regulators and politicians somehow failed to take from the financial crisis: the Masters of the Universe can’t even figure out what’s going on four floors down in their own buildings. The Bank of America accomplices even managed to miscalculate the bank’s regulatory capital for five full years before tipping off their bosses, showing the premeditation behind their scheme.

Or, the other possibility is that the banks are both incompetent and unmanageable. But that can’t be true, can it?

April 28, 2014

Retirement Accounts for Everyone

By James Kwak

The Connecticut legislature is considering a bill that create a publicly administered retirement plan that would be open to anyone who works at a company with more than five employees. Employees would, by default, be enrolled in the plan (at a contribution rate to be determined), but could choose to opt out. The money would be pooled in a trust, but each participant would have an individual account in that trust, and the rate of return on that account would be specified each December for the following year. Upon retirement, the account balance would by default be converted into an inflation-indexed annuity, although participants could request a lump-sum deferral.

The legislative session ends in less than two weeks, and while the bill has passed through committees, I believe it’s not certain whether it will be put to a floor vote. On Friday I wrote on op-ed for The Connecticut Mirror about the bill.

The requirements for businesses are relatively modest. The main one is that they have to allow employees to make contributions by payroll deduction. If they don’t outsource their payroll (which most companies do), that will involve a little more administrative hassle, but nothing terribly complicated. (Employers already have to deal with federal and state income tax withholding, payroll taxes, workers’ compensation insurance, and unemployment insurance contributions, to name a few.) And compared to a 401(k), this plan has the huge benefit that the employer isn’t a fiduciary. Retirement benefits are paid solely out of participants’ contributions and investment returns, so there’s no fiscal impact.

I think one controversial aspect of the bill, at least for some people, is the annually pre-specified rate of return. This is nothing new, by the way. TIAA-CREF, for example, has an account in its retirement plans that pays a pre-set rate of interest on a quarterly basis. But the downside is that if the interest rate is going to be guaranteed, it can’t be that high. In this respect the accounts will be similar to the myRA, which will pay an interest rate based on Treasury yields.

But if you want a guaranteed return, this is the way it has to be. One of the central rules of finance is that if you want a higher expected return, you have to be willing to take on more risk. So the underlying question is how much risk people without a lot of income should be taking in their retirement accounts. (For the most part, if you have a lot of income, you already have an employer-sponsored retirement account or a SEP-IRA if you’re self-employed.)

This is a question on which smart people differ. The argument for stocks is that they have a higher expected return, but that means they also have higher potential losses. While stocks tend to do better than other asset classes over thirty-year periods, there’s no fundamental reason why they have to (and there have been twenty-year periods during which they haven’t been the top asset class). My general thinking is adopted from Zvi Bodie: In finance, you should match your assets to your liabilities, and to the extent that your liabilities are fixed (i.e., the minimum you need to live in retirement), your assets should be as safe as possible. In addition, while stocks can be a better investment, they introduce countless possibilities for making bad investment choices, and human beings have tried out all of them.

In any case, I think SB 249 is a modest step forward. The underlying problem, unfortunately, is that many people just don’t make enough to save enough money for retirement. But that’s a much harder problem to solve.

April 24, 2014

I’m Shocked, Shocked!

By James Kwak

Technology-land is abuzz these days about net neutrality: the idea, supported by President Obama, (until recently) the Federal Communications Commission, and most of the technology industry, that all traffic should be able to travel across the Internet and into people’s homes on equal terms. In other words, broadband providers like Comcast shouldn’t be able to block (or charge a toll to, or degrade the quality of), say, Netflix, even if Netflix competes with Comcast’s own video-on-demand services.*

Yesterday, the Wall Street Journal reported that the FCC is about to release proposed regulations that would allow broadband providers to charge additional fees to content providers (like Netflix) in exchange for access to a faster tier of service, so long as those fees are “commercially reasonable.” To continue our example, since Comcast is certainly going to give its own video services the highest speed possible, Netflix would have to pay up to ensure equivalent video quality.

Jon Brodkin of Ars Technica has a fairly detailed yet readable explanation of why this is bad for the Internet—meaning bad for the choices available to ordinary consumers and bad for the pace of innovation in new types of content and services. Basically it’s a license to the cable providers to exploit a new revenue source, with no commitment to use those revenues to actually upgrade service. (With an effective monopoly in many metropolitan areas and speeds already faster than satellite, the local cable provider has no market pressure to upgrade service, at least not until fiber becomes more widespread.) The need to pay access fees will make it harder for new entrants on the content and services side; in the long run, these fees could actually be good for Netflix, since it won’t have to worry as much about competition. The ultimate result will be to lock in the current set of incumbents that control the Internet, ushering in the era of big, fat, incompetent monopolies.

Not only is this bad for consumers and for innovation, but it’s a reversal (or at least a severe watering-down) of the FCC’s earlier position on net neutrality, established in 2010 under a different FCC chair. Why did this happen? Well, look at this:

That’s from another article that Brodkin published yesterday, on the revolving door at the FCC. To summarize: Tom Wheeler, the current chair of the FCC, has previously been the CEO of the industry organizations for both the cellular industry (CTIA) and the cable industry (NCTA). The NCTA is currently headed by Michael Powell, a former chair of the FCC. The CTIA announced that its next CEO will be Meredith Attwell Baker. Her résumé goes like this: lobbyist for the CTIA; lobbying firms; National Telecommunications and Information Administration (part of the Department of Commerce), where she sided with Comcast against the FCC; FCC commissioner who voted for the Comcast-NBC merger (that’s Kabletown, for 30 Rock fans); head lobbyist for the NBC division of Comcast; and now CEO of the CTIA.

To put things in more familiar terms, this is roughly like Tim Pawlenty leaving the Financial Services Roundtable to become chair of the Federal Reserve and Ben Bernanke leaving the Fed to become head of the American Bankers Association, or Phil Gramm becoming a senior bank executive after shepherding the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act and the Commodity Futures Modernization Act. (Wait, one of those things actually happened.)

Many business groups like to say that they are against regulation because of free market, big government, economic efficiency, consumer choice, blah blah blah. But in fact, the history of regulation is one of large incumbents (or well-funded, well-connected newcomers) buying politicians and using them to extract rents, raise barriers to entry, erect tariff barriers, and do other things to pad the bottom line. Very occasionally, like in 2009–2010, people sit up and take notice. But most of the time, the casino is open and everyone looks the other way.

* There’s a separate issue about peering deals between different parts of the Internet backbone, which conceptually is a net neutrality issue, but is not addressed by the FCC’s net neutrality rules.

April 22, 2014

Where Do You Want to Be Born?

By James Kwak

That seems like a nonsensical question. Of course, each of us born where he or she was born, and we didn’t have much choice in the matter. But, philosopher John Rawls asked, if you lived behind a veil of ignorance, not knowing what position you would occupy in the socio-economic hierarchy, what rules would you choose to govern society?

Rawls was reasoning from a situation in which people could decide on any set of rules.* In the real world, the set of existing countries gives us a limited set of options to choose from; among those, if you didn’t know if you were going to be rich or poor, where would you choose to be born? On Friday, I was discussing this question with a scholar who is in the United States for a year, and one thing we noted was the instinctive tendency of many Americans to assume that we must be the best at everything and have the best of everything in the world (best health care, best Constitution, best hockey team, etc.).

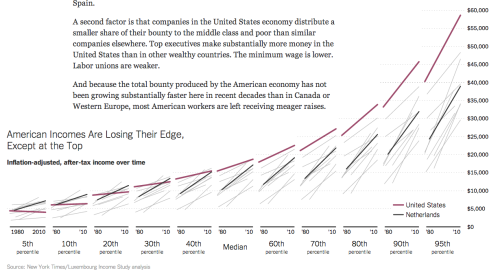

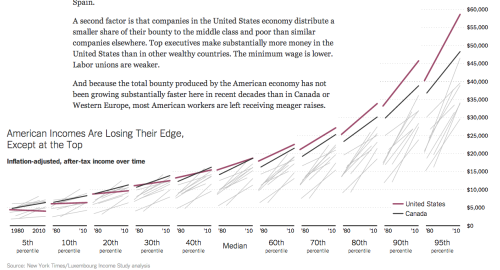

The data-driven answer is probably the Netherlands or Canada. Here are the changes in median after-tax per capita income in the Netherlands (black) and the United States (red) over the past three decades, courtesy of The New York Times (you can ignore the text that I included in the screenshot).

In words, poor people do a lot better in the Netherlands, middle income people do almost as well, and rich people do less well. Since the thing you want to hedge against is being born poor (and let’s not get into the question of social mobility, which makes the United States even worse), you should be willing to trade off extra income in the 95th percentile for extra income in the 5th percentile.

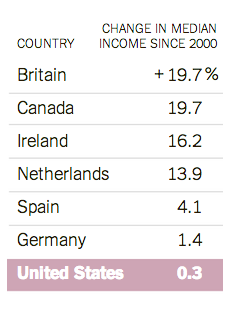

Canada also looks pretty good, and probably has a higher median income than we do today. (Norway looks even better, but that data series doesn’t go as far as the other ones.)

Canada also looks pretty good, and probably has a higher median income than we do today. (Norway looks even better, but that data series doesn’t go as far as the other ones.)

When you look at the red lines, this is just another way of looking at rising inequality. Note in particular the negative slopes for people in the 5th and 10th percentiles. But in comparative terms, it’s increasingly clear that while we like to think of ourselves as the richest country in the world (leaving aside a few anomalies like oil states and tax havens), that’s only true for practical purposes if you’re in the top half of the income distribution. Remember that rising tide floating all boats thing? Not so much.

Current trends are not in our favor, either:

There are lots of reasons for these outcomes, but one is a tax system that, by comparison with other advanced economies, takes less from the rich and redistributes less to the poor. And, of course, the current trend in tax policy is getting worse, not better, with the extension of most of the Bush tax cuts and the freezing of taxes on investment income at 20 percent.

How is any of this making ours a better country?

* This is the subject of a very brief and undoubtedly simplistic discussion in White House Burning, in the context of social insurance programs.

April 16, 2014

Rumsfeldian Journalism

By James Kwak

I still have Nate Silver in my Twitter feed, and I used to be a pretty avid basketball fan, so when I saw this I had to click through:

Just how bad were the @DetroitPistons‘ Bad Boys? http://t.co/q7A05JunDn#Detroitpic.twitter.com/SOOkfzCqq4

— FiveThirtyEight (@FiveThirtyEight) April 15, 2014

In the article, Benjamin Morris tries to analyze how “bad”* the Detroit Pistons of the late 1980s and early 1990s (Bill Laimbeer, Rick Mahorn, Dennis Rodman, etc.) were, with full 538 gusto: “That seems like just the kind of thing a data-driven operation might want to quantify.” But the attempt falls short in some telling ways.

First, Morris has to find a quantitative proxy for “badness.” He selects technical fouls. Huh?

Morris’s own sources define “badness” this way:

“physical, defense-oriented style of play” (Wikipedia)

“on-court mayhem” (Sports Illustrated, although in the original that’s in the same sentence as “class” and “smothering defense”)

“gritty, hard-nosed players who didn’t back down from anyone . . . the willingness to do seemingly anything to win (ESPN)

Morris runs with that last phrase and questionably defines it as unsportsmanlike conduct (even though most people associate the will to win with, say, Michael Jordan). From there, he uses technical fouls as a measure of unsportsmanlike conduct, concluding, “this stat is the closest we have to an official determination of ‘bad’ behavior.” (Foreshadowing: sometimes close isn’t good enough.)

That’s really weak. Any basketball fan old enough will tell you that the Pistons were known for physical play, for pushing and shoving under the basket and fouling rather than giving up layups, but none of this has anything to do with technical fouls. At the end of the day, Morris uses technical fouls because he doesn’t have anything else to use. This is called looking for your keys under the lamppost, and it’s generally considered a bad empirical method.

Morris then makes his argument even more tortured by saying that unsportsmanlike conduct alone does not constitute “badness”—it has to be unsportsmanlike conduct in the pursuit of winning: “For a team to earn a nickname prominently declaring how ‘bad’ it is, the players should be using their badness to make them better.” Now, it is true that the Pistons combined a high technical foul rate with a high winning percentage. But I’m mystified at what the point is here. We already knew that the Pistons were a very, very good team—we wouldn’t be talking about them otherwise. So I’m not sure how it adds anything to the analysis at this point.

Anyway, let’s stipulate for the point of argument that unsportsmanlike conduct constitutes “badness.” Morris makes the rather dodgy assumption that technical fouls accurately measure unsportsmanlike conduct. But there are other reasons why the Pistons might have gotten a lot of technical fouls. For one, once they acquired a reputation for being “bad,” referees almost certainly looked at them differently. Players’ reputations affect the calls that referees make against them; Larry Bird could complain about a call without getting a technical, while Dennis Rodman would get one for far less. In other words, technical fouls are partially measuring perceptions of badness. This means they are pretty unreliable as a vehicle for measuring the actual badness of a team that had a reputation for it.

This is pretty basic stuff when it comes to statistics. You have to think about whether a variable is an accurate measure of some underlying characteristic. But when technical fouls are all you have to deal with, you end up ignoring this kind of issue.

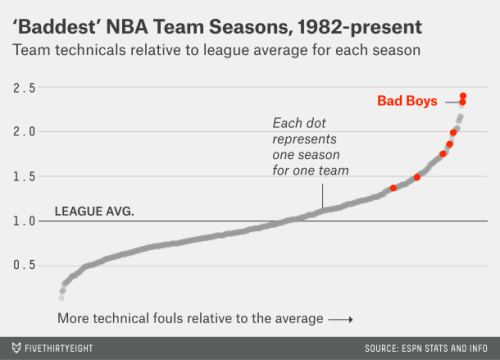

Finally, there is if not the worst chart of all time, certainly the worst chart produced by an outfit that claims to specialize in analyzing and presenting data:

The observations are individual team-years. The Y axis is the team’s technical fouls divided by the league average for that year. What’s the X axis? It says “More technical fouls relative to the average,” but that could just as well be the label for the Y axis.

I’m pretty sure that all the team-years are just arranged sequentially from left to right, from fewest relative technicals to most relative technicals. Which is a pretty unhelpful way to display this information. If you only have one dimension (number of technicals), you don’t need a chart: just say the Pistons had 7 out of the top X seasons, including the top 2, and save the ink. If you want to show the extent to which the Pistons were outliers, use a frequency distribution so we can see the mode around 1 and the Pistons out in the tail. Don’t use two dimensions to tell a one-dimensional story.

Donald Rumsfeld famously said, “You go to war with the army you have.” Well, this is what happens when you try to answer a vague and complicated question but you only have one data series—and not a particularly appropriate one.

Morris triumphantly concludes, “For once, a harder look at the data seemingly confirms rather than undermines a popular sports narrative.” I think XKCD (see the previous link) still has the last word.

* “Not bad meaning bad but bad meaning good,” that is.

April 15, 2014

Defending Kickbacks

By James Kwak

The Wall Street Journal reports that the SEC will soon decide (well, sometime this year) whether brokers should be subject to a fiduciary standard in their dealings with clients, as registered financial advisers are today. At present, brokers only need to show that investments they recognize are “suitable” for their clients—roughly speaking, that they are in an appropriate asset class.

Not surprisingly, the brokerage industry is up in arms. They want to be able to push clients into the products for which they receive the highest commissions—a practice that (they say) could be more difficult under a fiduciary standard. According to one lobbyist,

“a universal fiduciary standard could end up hurting many investors. Lower- and middle-income investors often turn to brokers who are compensated through product commissions, he says, because such clients are less attractive to financial advisers who are compensated based on a percentage of assets under management. Higher costs could prompt some brokers to drop commission-based accounts in favor of more-lucrative accounts that charge a percentage of assets under management, leaving many lower- and middle-income investors without anyone to turn to for investment advice.”

(That’s a paraphrase by the Journal writer, not a direct quotation.)

First of all, note the underlying chutzpah here. The SEC is thinking of requiring brokers to act in the interests of their clients. The defense is, “We’ll have to change the way we do business.” How is that not an admission that they aren’t currently acting in the interests of their clients?

Second, let’s dig into the supposed benefits of commissions. Another word for “commissions” is “kickbacks.” Basically what’s going on is that some mutual fund company is charging a, say, 5 percent load, and then it’s paying some of that back to the broker who steered you into the fund. In other words, the only reason the fund company is paying a kickback to the broker is that it is making an even higher profit from the customer.

With the sales load, it’s obvious. But it’s also the case for a “no-load fund” with a high expense ratio. Brokerage commissions are not supposed to be included in fund expense ratios. But expense ratios do include 12b-1 fees, which are used to pay kickbacks to brokers.* Again, the kickback is just a way for the fund company to share with the broker the excess profits it earns from the customer who buys that fund—as opposed to, say, the index fund with an expense ratio of 10 basis points or less.

Now, sales commissions can make sense in some markets. For example, say there are two products in the market. A is worth $100 and costs $100 to make; B is worth $110 and costs $100 to make. But only professionals know which is worth more. In that case, if B is priced at $108 and $4 of the profits go to the broker as a commission, then your broker is more likely to steer you into B, and everyone is better off. (Of course, on these facts, the broker would still steer you into B even with the fiduciary duty, so a fiduciary duty rule would do no harm.) Or there can be a market in which ordinary customers have to go through brokers—that is, every product has a sales charge, one way or another.

But that’s not the case with mutual funds in liquid asset classes, which you can buy directly from Vanguard, Fidelity, and many others. There’s no reason to believe that, on an expected basis, a higher-priced product (in expense ratio terms) will have higher returns than a lower-priced product. Higher-fee funds are a combination of higher expenses on pointless things (“research,” trading costs) and higher profits for the fund company, which they are willing to share with brokers as a cost of doing business.

In other words, the sole reason the broker gets a commission is that he is selling you a worse product than the low-fee index fund. The excess profits and the kickback go together; you can’t have one without the other. If brokers choose to drop lower-income clients, then said clients are better off for not getting bad advice. If they need advice, then they should consult a fee-only adviser; the amount they spend in fees will be more than made up in avoiding poor investments recommended by brokers with hidden agendas.

* The Investment Company Institute, apparently in all seriousness, says, “Rule 12b-1 plans have provided an important addition to the choices investors have in how to pay for their fund shares.” Like, you could pay less, but now you can choose to pay more!

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers