Simon Johnson's Blog, page 19

March 28, 2014

Stress Tests, Lending, and Capital Requirements

By James Kwak

Despite the much-publicized black eye to Citigroup’s management, the bottom line of the Federal Reserve’s stress tests is that every other large U.S. bank will be allowed to pay out more cash to its shareholders, either as increased dividends or stock buybacks. And pay out more cash they will: at least $22 billion in increased dividends (that includes all the banks subject to stress tests), plus increased buyback plans.

Those cash payouts come straight out of the banks’ capital, since they reduce assets without reducing liabilities. Alternatively, the banks could have chosen to keep the cash and increase their balance sheets—that is, by lending more to companies and households. The fact that they choose to distribute the cash to shareholders indicates that they cannot find additional, profitable lending opportunities.

This puts the lie to the banks’ mantra that capital requirements will constrain lending and therefore reduce growth (made most famously in the Institute of International Finance’s amateurish report claiming that increased regulation would make the world’s advanced economies 3 percent smaller). Capital isn’t the constraint on bank lending: it’s their willingness to lend.

Let’s look at this a little more closely. Let’s say that, instead of letting the banks increase their dividends and buybacks, the Federal Reserve increased capital requirements and said that banks had to hold onto their cash to meet those higher requirements. What would happen to bank lending? Nothing. Banks wouldn’t have to reduce their balance sheets because they already have the cash; they would just be not paying it out to shareholders.

The counterargument is this: banks only want to lend if their expected rate of return exceeds their cost of capital; but higher capital requirements increase the cost of capital (because equity capital is more expensive than debt capital); therefore the set of attractive lending opportunities will shrink.

But this is a fallacy, as spelled out by Admati and Hellwig in The Banker’s New Clothes. According to Modigliani-Miller, capital structure doesn’t affect the overall cost of capital, so retaining cash shouldn’t reduce the set of attractive lending opportunities. We all know Modigliani-Miller doesn’t hold in the real world, but the main reason it doesn’t hold is the tax subsidy for debt. (The second-biggest reason it doesn’t hold is agency costs, which dictate that more debt is bad.) In other words, to the extent that more debt lowers the cost of capital, it’s due to a distorting government intervention. The lower cost of capital due to increased leverage is a social bad, not a social good.

Bank CEOs can’t have it both ways. If the best use of their cash really is returning it to shareholders, then they might as well be keeping it in their accounts at the Federal Reserve. And that way we would have safer banks, and a safer financial system.

March 26, 2014

A Book That Needed To Be Written

By James Kwak

I have previously written about (here, for example) what I call economism, or excessive belief in the little bit that you remember from Economics 101. The problem is twofold. First, Economics 101 usually paints a highly stylized, unrealistic view of the world in which free markets always produce optimal outcomes. Second, most people in the world who have taken any economics have only taken first-year economics, and so they never learned that, from a practical perspective, just about everything in Economics 101 is wrong. (Complete information? Rational actors? Perfectly competitive markets?) This produces a nation of people like Paul Ryan, who repeats reflexively that free market solutions are always good, journalists who repeat what Paul Ryan says, and ordinary people who nod their heads in agreement.

The problem is not the economics profession per se. These days, to make your mark as an economist, it helps to be arguing (or, better yet, proving) that the free market caricature of Economics 101 is wrong. The problem is the way it is taught to first-year students, which pretty much assumes that Joseph Stiglitz, Daniel Kahnemann, Elinor Ostrom, and many others had never existed.

What we need, I have often thought, is a companion book for students in Economics 101, one that points out the problems with the standard material that is covered in the textbook. For a while I was thinking of writing such a book, but I decided against it for a number of reasons, one of them being that I am not actually an economist. Fortunately, John Komlos, who really is an economist, has written a book along these lines, titled What Every Economics Student Needs to Know and Doesn’t Get in the Usual Principles Text.

Komlos’s book takes aim at what he calls “market fundamentalism,” the ideology that markets are always good. Like all successful ideologies, market fundamentalism pretends not to be an ideology, which is why it likes to dress up in mathematical equations. But as most people in most other social sciences would agree, ideology is inescapable. Komlos is explicit about his: the goal of economics should be to improve people’s quality of life, which includes the ability of people to live meaningful lives. He also seems to agree that there is nothing wrong with the field of economics in itself: the problem is that many of the most important developments in economics have been left out of introductory courses and textbooks. The result is that “most students of Econ 101 . . . are never even exposed to the more nuanced version of the discipline and are therefore indoctrinated for the rest of their lives” (pp. 10–11).

Most of the book after the first couple of chapters presents specific criticisms of the basic models presented in Economics 101. Chapter 3, for example, discusses the problems with assuming that consumer demands are exogenously determined and that indifference curves are smooth and reversible (that is, ignoring the fact that we experience loss aversion in considering changes in consumption levels). Chapter 4 summarizes the evidence against the assumption of the rational decision maker and discusses what that means for the principle of utility maximization. And so on.

The book covers a lot of topics, many of which could warrant much further discussion. But it should do an excellent job at its primary mission: showing first-year students that most of what they learn cannot be applied in the real world, at least not without significant modification. The world is a complex, messy place, and markets are complex, messy institutions like any others. The more people learn that lesson, the better.

March 25, 2014

More on Wasting Shareholders’ Money

By James Kwak

A few weeks ago I wrote a post about my most recent “academic” paper, on the issue of whether corporate political contributions might constitute a breach of insiders’ fiduciary duty toward shareholders. The thrust of that paper was that some political contributions could be contested as breaches of the duty of loyalty—for example, if a CEO causes the corporation to give money to a candidate who promises to lower the CEO’s individual income taxes—which would result in the courts applying a higher standard of review.

Joseph Leahy, another law professor, recently directed me to a paper that he wrote last year (but is still being edited for publication in the Missouri Law Review) on basically the same topic. He argues first that corporate political contributions do not qualify as “waste” (which has a precise legal definition), barring the kind of extreme facts that you only see in law school hypotheticals. I agree with that, although my only discussion of the point was in a footnote (79).

Second, Leahy argues that a corporate political contribution might qualify as self-dealing, citing in particular the example where a CEO directs a corporate donation to the candidate who is best for his personal taxes. As Leahy says, “it is certainly plausible that a jury would conclude that a corporate political donation constitutes self-dealing by the corporation’s rich directors or offices, even if the contribution also plausibly benefits the corporation” (p. 88).

Leahy does strike a slightly different tone than I do. On balance, although he finds this line of attack plausible, he thinks it is likely to fail in most circumstances. The problem, he writes, is that “any financial benefit to the director or her proxies will be indirect and highly uncertain, so plaintiffs will have to show that the financial benefit was sufficiently important in order to be material to the donor” (p. 96). One problem with establishing materiality is that, in general, an individual donation is unlikely to affect the outcome of an election. (But if we’re going to say that contributions are immaterial on that ground, then we’re halfway down the rabbit hole, since the same could be said of all political contributions, which brings us back to where we started: why do corporations do this with shareholders’ money?)

I do agree with Leahy that this type of challenge is likely to fail in most circumstances, given the current attitudes of our courts. But I also think that there is enough precedent in the cases for the Delaware Chancery Court to uphold such a challenge, if one of the chancellors wants to.

March 24, 2014

Stopping Russia

By Simon Johnson

The rhetoric of confrontation with Russia seems to be escalating, including with the remarkable suggestion – from Mike Rogers, the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee – that the US provide “small arms and radio equipment” to Ukraine.

Encouragement for a military confrontation is not what Ukraine needs. As Peter Boone and I have argued in a pair of recent columns for the NYT.com’s Economix blog, Ukraine needs economic reform (with a massive reduction in corruption as the top priority). This reform requires, above all, a massive and immediate reduction in – or elimination of – corruption.

Throwing a lot of external financial assistance at Ukraine’s government, for example with a very large loan from the International Monetary Fund, is unlikely to prove helpful. Based on recent prior experience, such lending may even prove counterproductive.

And this seems to be exactly the path that our foreign policy elite has placed us on.

March 21, 2014

Skew

By James Kwak

There is a common phenomenon in legal disputes over the value of something, be it a company, a piece of land, or a person’s expected lifetime earnings. Each side hires an “expert” who produces an estimate based on some kind of model. And miraculously, every single time, the expert for the party that wants a higher number comes up with a high number, while the expert for the party that wants a lower number comes up with a low number. No one is surprised by this.

Yesterday, the Federal Reserve posted the results of the latest periodic bank stress tests mandated by the Dodd-Frank Act. For these tests, the Fed comes up with various scenarios of how things could go badly in the economy, and the goal is to see how banks’ income statements and balance sheets would respond. The key metrics are the banks’ capital ratios; the goal is to identify if, in bad states of the world, the banks would still remain solvent. If not, the banks won’t be allowed to do things that reduce their capital ratios today, like paying dividends or buying back stock.

For the most part, the results look pretty good: capital levels even under the severely adverse scenario should remain above the levels reached during the 2008–2009 crisis. (Of course, there are several huge caveats here. You have to believe: first, that the scenarios are sufficiently pessimistic; second, that the banks’ current financials are accurately represented; third, that the model is sensible; and fourth, that the capital levels set by current law are high enough.)

But there’s something else going on here. As part of the stress testing routine, each bank is supposed to do its own simulation of how it would respond to the scenarios specified by the Fed, using its own internal model. And—surprise, surprise!—the banks virtually uniformly predict that they will do better than the Fed.

At the high end, Goldman Sachs and Citigroup predict that they would have capital levels 3.9 and 3.0 percentage points, respectively, higher than expected by the Federal Reserve. Since the Fed predicted minimum Tier 1 capital levels for these two banks of 6.8 and 7.0 percent, those are huge differences: 57 percent higher for Goldman and 41% higher for Citi. The other four big banks also claimed their capital levels would be 0.2 to 2.6 percentage points higher than in the Fed’s model.

Now if everyone were being above board here, the expected difference between the banks’ estimates and the Fed’s estimates should be zero. But of course that’s not the case. Banks do things to make money, and in this exercise their goal is to make the case that they can get by with less rather than more capital. There are honest differences of opinion on how to model things, but you can systematically make plausible choices that produce higher rather than lower numbers. And that’s almost certainly what’s going on. Which means that the banks’ estimates aren’t worth the electrons who died (OK, not literally) sending them to you across the Internet.

But, you may be thinking, isn’t the Federal Reserve systematically trying to produce low numbers? Not necessarily. The Fed’s incentive in the first instance isn’t to force banks to maintain more capital; it’s to make sure that banks are holding the right amount of capital. The Fed is supposed to protect the financial system and ensure economic growth, so if you believe in the capital-growth tradeoff, the Fed doesn’t have an incentive to force banks to hold lots of capital. (And if you don’t believe in it, then you should already agree with Admati and Hellwig that every bank should have lots more capital.) In other words, Fed economists don’t make any more money by arguing that banks need more capital.

Although there’s no a priori reason why the Fed as an institution would want banks to hold more capital, it’s also possible that the specific people at the Fed do think that banks should be holding more capital, and they are using the stress tests as a backdoor way to push that agenda. But if that’s the case, there’s another, more powerful tool they should be using: they should be boosting the leverage ratio (which, counterintuitively, is measured as equity over assets, not debt over equity).

Finally, this whole thing proves a point that I argued a long time ago: capital doesn’t exist as an object in the world. It’s inherently probabilistic, since it is based off of the values of things whose value depends on unknown probability distributions. That’s why it’s possible for Goldman to argue with a straight face that its capital will be 57 percent higher in some state of the world than the Federal Reserve thinks it will be. And that’s why, if you’re counting on capital requirements to protect the financial system from disaster, you had better err far on the side of safety.

March 20, 2014

Whiskey Costs Money

By James Kwak

A few days ago I wrote a post that began with New York Fed President William Dudley talking tough about banks: “There is evidence of deep-seated cultural and ethical failures at many large financial institutions.” The thrust of that post was that I’m not very encouraged when regulators talk about culture and the “trust issue” but don’t indicate how they are going to actually affect industry behavior.

As they say, talk is cheap, whiskey costs money. What’s more important than what regulators say is what they do—and don’t talk about. Peter Eavis (who wrote the earlier story about bank regulators that my previous post was responding to) wrote a new article detailing how that same William Dudley has delayed the finalization of the supplementary leverage ratio: the backup capital standard that requires banks to maintain capital based on their total assets, not using risk weighting.

Dudley has said, “I do not feel that I in any way hold any allegiance or loyalty to the financial industry whatsoever.” That may be true; he certainly made enough at Goldman that he has no real financial incentive to continue to make nice with Wall Street.* Yet at the same time he appears to be parroting concerns raised by some of the big banks, raising a concern about the leverage rule that Felix Salmon calls “very silly” and that, according to Eavis, the Federal Reserve mother ship in Washington didn’t consider significant.

In the grand scheme of banks and their allies weakening and slowing down new regulation, this is probably not a particularly momentous battle. But it does put things in perspective.

* Of course, we know that among some people (many of whom live in New York and work in finance), no amount of money is ever enough.

March 18, 2014

There’s No Substitute for the Government

By James Kwak

Mike Konczal wrote an excellent article for Democracy about the problems with a voluntary safety net and the superiority of government social insurance. The article draws on serious historical research (by other people) to prove two main points: first, there never was a Golden Age of purely voluntary charity; second, and more important, what charitable support mechanisms existed were not up to the challenges of the Second Industrial Revolution of the late nineteenth century and completely collapsed with the onset of the Great Depression.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise. There are basic economic reasons why public social insurance is superior to voluntary charity. The goal here is to protect people against risk: of unemployment, of health emergency, of outliving one’s savings, and so on. For a risk-mitigation scheme to work, there are a few things that are necessary. One is that people actually be covered. This is something you can never have with a private system (unless it’s regulated to the point of being essentially public), since charities get to pick and choose whom they want to help. As Konczal says of private agencies before the Depression,

“They were also concerned they’d lose their ability to stigmatize—or to protect—various populations; by playing a role in determining who wasn’t deserving of assistance, they could shield those they felt worthy of their support.”

Another thing you want is the assurance that the system has the financial capacity to actually protect you in the event of a crisis. That’s why you don’t depend on your neighbors to rebuild your house if it burns down. Besides the fact that they may not like you, they probably don’t have enough money—especially if you lose your house in a fire that burns down the entire neighborhood. As I’ve said many times before, there is no other entity in the country—and not really one in the world—with the financial capacity of the federal government. Even state governments scramble to cut benefits when push comes to shove, which is one reason why some states provide Medicaid coverage to almost no one.

We like to think that we are a nation of generous people who will help each other out, but that isn’t really true. We do have a much larger charitable sector than other advanced economies, where the state shoulders more of the burden. But more than half of our total donations go to religious organizations, private schools, and medical organizations, with only 12 percent going to human services organizations. Some money does filter from other organizations to the poor, but at most you can get to one-third of the total. (The vast majority of my donations have gone to services for the poor, primarily legal services.) I’ve argued elsewhere that we should place limits on the tax deductibility of charitable contributions, which are effectively a way that rich people can force other taxpayers to contribute to their pet charities. But as long as we have this idealized picture of our charitable sector, it isn’t going to happen.

March 17, 2014

You Don’t Say

By James Kwak

Last week Peter Eavis of DealBook highlighted a statement made last year by New York Fed President William Dudley (formerly of Goldman Sachs, then a top lieutenant to Tim Geithner): “There is evidence of deep-seated cultural and ethical failures at many large financial institutions.” There was a point, say in 2008, when many people probably thought that our largest banks were just guilty of shoddy risk management, dubious sales practices, and excessive risk-taking. Since then, we’ve had to add price fixing, money laundering, bribery, and systematic fraud on the judicial system, among other things.

Eavis also tried to make something positive out of a couple of other recent comments. Dudley said, “I think that trust issue is of their own doing—they have done it to themselves,” while OCC head Thomas Curry said, “It is not going to work if we approach it from a lawyerly standpoint. It is more like a priest-penitent relationship.”

I don’t see much reason for optimism. First, framing the problem as a “trust issue”—customers no longer see banks as trustworthy institutions—is beside the point. Wall Street’s main defense is that its clients already realize that investment banks do not have their buy-side clients’ best interests at heart, and clients who don’t realize that are chumps. And in the wake of the financial crisis, I suspect there are few individuals out there who believe that their banks are there to help them. The banking industry has discovered that it can thrive without trust, which is not surprising; retail depositors trust the FDIC, and bond investors know that trust isn’t part of the equation.

Second, when an entire industry shows a deep proclivity to flaunt the law, it’s distressing that one of its top regulators sees himself more as a priest than as a lawyer. With a priest, the presumption is that the congregant actually wants to be saved, and therefore will listen to the priest. Wall Street banks just care about profits, which is only natural. Once they’ve learned that they can be profitable without being ethical, there’s no turning back. The only way to change the equation is to make lawbreaking unprofitable, which means serious penalties, both civil and criminal.

In that vein, the SEC is especially proud of a judge’s decision last week to impose an $825,000 fine on Fabrice Tourre, the Goldman employee implicated in the ABACUS deal. The SEC’s enforcement director claimed that the penalty reflected “the S.E.C.’s intent of pursuing meaningful sanctions to punish individuals responsible for misconduct and deter others from violating the federal securities laws.” If only.

That is a meaningful sanction, particularly because the judge prohibited Goldman from covering Tourre’s penalty of $650,000. I doubt, however, that she could stop Goldman employees from individually gifting cash to Tourre. And, if they have any kind of sense of fairness, they should start passing the hat—because Tourre was the only one out of probably thousands of people engaged in similar behavior who got busted. Which means that, if you want to structure deals so they are likely to collapse and lie about it to your buy-side clients, the odds are spectacularly in your favor. More important, if you are a senior executive and you want to pressure your employees (including by promising them huge bonuses) to structure deals that are likely to collapse and lie about it to your buy-side clients, the odds in your favor approach certainty.

Talk is cheap. But ultimately, it’s hard to see how anyone’s behavior is going to change with the regulators we’ve got.

Insurance Companies and Systemic Risk

By James Kwak

The systemic risk posed by insurance companies is something that I’ve never been entirely clear about. I know it’s an enormous issue for large insurers who want to avoid additional oversight by the Federal Reserve. I’m well aware of the usual defense, which is that insurers are not subject to bank runs because their obligations are, in large measure, pre-funded by policyholder premiums, and policyholders must pay a price in order to stop paying premiums. But this has never seemed entirely convincing to me, because some insurers are enormous players in the financial markets, and the nature of systemic risk seems to be that it can arise in unusual places.

So I find very helpful Dan and Steven Schwarcz’s new paper discussing the ins and outs of systemic risk and insurance. Because it’s written for a law review audience, it covers all the basics, so you can follow it even if you know little about insurance. They cover the usual arguments for why insurers do not pose a threat to the financial system, but then posit a number of reasons for why they could pose such a threat.

A big reason is that insurers make up a large proportion of the buy side, especially for particular markets—owning, for example, one-third of all investment-grade bonds. Furthermore, insurers tend to concentrate their purchases within certain types of securities that provide them with regulatory benefits (sound familiar?)—such as the structured products that promised higher yield while providing the investment-grade ratings that insurers needed. The big fear is that large numbers of insurers could be forced to dump similar securities at the same time, causing prices to fall and harming other types of financial institutions. This may seem unlikely, since insurers only have to make cash payouts when insurable events occur (houses burn down, people die). But insurers have to meet capital requirements just like banks, so falling asset values will require them to adjust their balance sheets.

Another major problem is that it’s not clear that insurers are prepared for those insurable events. For example, insurers are not prepared for a global pandemic, just like they weren’t prepared for large-scale terrorist attacks prior to September 11, 2001.

Finally (and I’m skipping several factors), it’s possible that entire segments of the insurance industry are under-reserving for certain types of risks. This stems from the usual cause: companies compete for market share, and the way to win share is to charge lower prices, and the way to charge lower prices is to underestimate risk. This is all good in the short term, resulting in larger bonuses, and bad in the long term, when the risk actually materializes. Yet it seems that insurance regulators are shifting to “a process of principles-based reserving (‘PBR’), which would grant insurers substantial discretion to set their own reserves based on internal models of their future exposures.” For even a casual observer of the last financial crisis, this sounds like the system is taking on a large amount of model risk and regulatory competency risk, and we know how that story ended last time.

Schwarcz and Schwarcz conclude that the federal government should play a larger role in monitoring systemic risk in the insurance industry, which will make them just about the least popular people in most insurance circles. Given the downside risks, though, it seems like pretending that there’s no reason to worry about insurers is not a good long-term strategy.

March 14, 2014

The Cost of Comp Plans

By James Kwak

Enterprise software is the industry that I know best. Both of the real companies I worked for (sorry, McKinsey is a fine institution in many ways, but it isn’t a real company) were in enterprise software: big, complicated, expensive software systems for midsize and large companies that can take years to sell.

Although the development of enterprise software is (often) highly sophisticated, sales is typically governed more by tribal custom. One trait we probably shared with other big ticket, business-focused industries is the “comp plan”: the system for calculating salespeople’s commissions on sales. The comp plan is just about the most important thing to any red-blooded salesperson. (Its only competition would be the territory assignment, which determines what companies he is allowed to sell to—or, more specifically, for sales to what companies he will earn a commission.) It is the source of months of lobbying, the subject of intense executive- and even board-level scrutiny, and the target of almost every complaint.

The typical comp plan—and most software companies conform pretty closely to the same model—is a weird animal, probably not what you would come up with were you designing it from scratch. Salespeople get a percentage of each sale, but that percentage rises with their cumulative sales: some relatively low percentage until they reach some predetermined “quota” (within the comp plan, the biggest source of resentment), then a higher percentage, and then much higher percentages as their sales increase beyond quota. Quota may be set for a quarter or for the year. The system is often engineered so that a salesperson who exactly reaches quota will be paid some predetermined “target total compensation” in the upper-middle class range; this means that the salesperson who doubles or triples his quota will make far, far more. (Top salespeople make more money than just about anyone else, except the CEO and maybe a few other executives.)

For whatever reason, the conventional wisdom is that salespeople are motivated entirely by their personal compensation—as opposed to most people in most other jobs, like the engineer who will work nights and weekends knowing that, at most, it will earn him a few extra percentage points in his next annual raise. This doesn’t have to be true, and I have certainly known many salespeople who cared deeply about the companies they worked for. But that assumption is what shapes the comp plan, which then tends to attract people who care only about their personal compensation.

The economist looking at this plan would immediately realize that this creates the incentive to time the closing of deals so that they fall in the period where they will result in the highest commission. All things being equal, it’s better to land four deals in one quarter than one each in four quarters. The salesperson looking at this plan realizes the same thing.

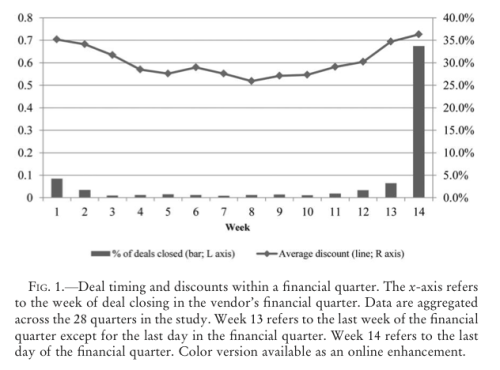

In a new paper, Ian Larkin (JSTOR; SSRN) analyzes the effects of this type of comp plan by looking at a proprietary dataset of close to 8,000 deals closed by a single software company. (About 1,100 per year, 412 total salespeople over a seven-year period, average deal size around $350,000, average discount over 30%—any guesses?) The effect on deal timing is striking:

So is the effect on revenue. For each deal, Larkin calculates how much more or less the salesperson would have earned had it closed either one quarter before or one quarter later. He also estimates the increased discount that the salesperson gave in order to get the deal to close in the quarter that was best for him. (Note that discounts are highest at the beginning and end of the quarter; I don’t think I’m giving away an insider’s secret here.) The bottom line is that this software company lost about 6–8% of its revenue because of the timing incentives created by the comp plan.

Why do we do this? One possibility is that it may still be the rational thing to do. It’s possible that the comp plan causes salespeople to work harder, and that more than compensates for the timing problem. Another possibility that Larkin raises is that this type of plan is particularly attractive to overconfident salespeople and causes them to work harder than they rationally should (because they base their effort on the expectation of getting accelerators, even though the chances of them doing so are relatively low).

Still, it seems like you should be able to design something more rational. My guess is that the real problem would be selling a different plan to any kind of experienced salesforce, which would generally assume that you were trying to lower their pay. That is, the suspicion and discord (and attrition) it would generate would not be worth the higher level of efficiency. So it wouldn’t surprise me too much if, fifty years from now, the technology of the future is still sold the way IBM sold mainframes half a century ago.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers