Simon Johnson's Blog, page 30

November 26, 2012

Rewriting History

By James Kwak

This morning Matt Yglesias wrote a post arguing that the December 2010 tax cut was an Obama victory. By the time this evening that I finally found time to figure out what annoyed me about it, I had to go to the second page of his blog to find it, since he had posted so much in the interim. That man sure can write.

I’m not so sure about his memory, though. Yglesias says Obama won because he got the (Bush) middle-class tax cuts extended along with some other goodies like a payroll tax cut and extended unemployment benefits, and all he had to give up was an extension of the (Bush) upper-income tax cuts. The reason people think it was not a good deal, he says, was that “to get a favorable deal Obama had to downplay the extent to which he hadn’t given anything up.”

That certainly wasn’t the line the administration was taking at the time. Remember Austan Goolsbee’s YouTube video? Or the “we got more than they did” slide that the White House was passing out to anyone who would listen? The administration was busily arguing that, in the race to see who got more of “their” tax cuts, the Democrats had won.

But this cleverly ignores the fact that Republicans like all tax cuts. Sure, they like to cut capital gains taxes for the rich more than the like child tax credits for the poor—but still, it was George W. Bush who expanded those child tax credits! As I said at the time:

“If you’re Grover Norquist and what you want more than anything else is lower tax revenue, you should be celebrating like it’s Christmas and your birthday at the same time. We had an argument where one side wanted tax cuts A, the other side wanted tax cuts B, and they compromised by adding tax cuts C?”

And sure, Republicans want some tax cuts (lower income tax rates) to be permanent, and they don’t want other tax cuts (lower payroll tax rates) to be permanent. But that doesn’t mean they’ll say no to two years of lower payroll taxes, since when you’re trying to starve the beast, every morsel you can snatch out of its hungry jaws helps. For Norquist, that’s not a concession—it’s an extra dessert sent out by the chef, on the house.

Does any of this mean anything for today? Whether Obama is a good or a bad negotiator is of secondary importance. What really matters is what he wants. What Obama showed two years ago, and what he has maintained ever since, is that his top priority is extending the Bush tax cuts for the “middle class.” (“Middle class” should always be in quotation marks because (a) Obama’s plan would maintain tax cuts up to about $300,000 in gross income* per household and (b) people who make more will still benefit from the tax cuts on the first $300,000 of their income.)

That is more important to him than protecting social insurance programs. We know that since he’s been willing to offer major concessions on that front (e.g., changing the COLA formula for Social Security) in the past. We also know that since the Bush tax cuts—most of which Obama wants to keep—are precisely what is creating the revenue shortfall that puts Medicare at risk. That worries me more than whether or not he is a good negotiator.

* The commonly advertised number is $250,000, but that is before indexing and after deductions and exemptions.

Grover Still Matters

By James Kwak

Last week I wrote a post arguing that Grover Norquist’s Taxpayer Protection Pledge is alive and well and still a binding constraint on Republican lawmakers. The media continue to push the story of Republicans renouncing the pledge, however, and who knows, I could turn out to be wrong. Maybe some Republicans will vote to reduce deductions without a compensating reduction in marginal rates.

Even in that world, however, the pledge will still have a major impact. All this focus on the pledge makes it seem as if the few apostates—Peter King, Lindsey Graham, etc.—are making some enormous, admirable stand on principle. In fact, all they are saying is that they might be willing to close a few loopholes and keep tax rates where George W. Bush left them; they are still adamantly opposed to increases in tax rates (even though those increases, set to take effect on January 1, are the result of Bush’s choosing to use reconciliation to pass his tax cuts).

The specter of the pledge has allowed them to dress up a tiny concession—conservatives should want to get rid of distortions anyway, since they distort economic choices—as a major move to the center. In return for breaking the pledge, they can demand that Democrats agree to major changes to entitlement programs.

The tactical beauty of the pledge is that it credibly committed the Republican Party to never increase taxes, thereby forcing Democrats to meet them not in the middle, but all the way over on their side. (See the tax compromise of December 2010 and the debt ceiling compromise of August 2011, for example.) Even if a few signatories break free, it will still have much the same effect.

November 22, 2012

Mary Miller vs. Neil Barofsky For The S.E.C

By Simon Johnson

The Obama administration is floating the idea that Mary J. Miller, under secretary for domestic finance at the Treasury Department, could become its nominee to lead the Securities and Exchange Commission. Ms. Miller, a longtime executive in the mutual funds industry, has served in the Treasury under Timothy Geithner since February 2010.

Ms. Miller represents the financial sector’s preferred approach to financial reform – some rhetoric but very little by way of serious effort. She has no time for people who are serious about making the financial system safer. And there is no willingness to really face down powerful people on Wall Street.

Her potential candidacy faces three major obstacles: Neil Barofsky, money market funds and the new momentum for reform.

Mr. Barofsky is the most important obstacle because, as soon as you think about him, you see an instantly plausible chairman for the S.E.C. The former special inspector general for the troubled assets relief program, or TARP, he is an experienced prosecutor who understands complex financial fraud. For example, he brought Refco Inc. executives and their legal advisers to justice in the mid-2000s (this was a commodities giant where top people engaged in accounting fraud). And he’s tough – taking on Colombian drug traffickers early in his career. Most recently, he confronted Mr. Geithner over the implementation of TARP – pushing for answers on why bailout terms were so favorable for big banks and so unfavorable for everyone else. He also pursued a number of securities fraud cases, including one involving Colonial Bank, which illegally obtained more than half a billion dollars from TARP — before Mr. Barofsky’s office stopped that fraud in its tracks and eventually obtained one of the few high-level convictions resulting from the financial crisis.

Mr. Barofsky’s account is published in his highly readable book, “Bailout: An Inside Account of How Washington Abandoned Main Street While Rescuing Wall Street.” Mr. Barofsky understands as much about finance as anyone in the industry, and no one would ever think he was captured by the world view of big banks.

Mr. Barofsky is a lifelong Democrat who has enjoyed bipartisan support in Congress. Since I suggested Mr. Barofsky’s name in a post last week, there has been an outpouring of support. A petition that Credo Action has put online urging President Obama to appoint an S.E.C. chairman who will hold Wall Street accountable, and naming Mr. Barofsky as a worthy choice, had more than 35,000 signatures by Wednesday morning.

The petition also recommends former Senator Ted Kaufman of Delaware and Dennis Kelleher of Better Markets – both of whom I endorsed here last week – and it expresses support for Sheila Bair, who would be terrific for the job (in a separate column last week, I said she was one of five people who deserve serious consideration to be Treasury secretary).

The White House does not like to take public suggestions of names for prominent positions; the Washington way is to do everything behind closed doors. And Mr. Barofsky is not popular with Mr. Geithner, precisely because he has stood up to authority for all the right reasons.

Still, considering Mr. Barofsky as a potential nominee makes the case for Ms. Miller look very weak.

She has no experience as a regulator or as an enforcer of the law. She has never worked on securities fraud. And she has no track record of standing up to powerful vested interests; in fact, she helped push the recent JOBS Act, which greatly undermine the protections available to investors. In addition, her work experience is entirely within the mutual fund industry – 26 years at T. Rowe Price. And a major agenda item now for the S.E.C. is mutual funds and how to make them less vulnerable to the kind of runs that occurred in September 2008. (For a primer, please see my recent column for Yahoo Finance.)

The mutual-fund industry does not want reform, and it worked long and hard to keep Mary Schapiro, the departing S.E.C. chairwoman, from pushing forward some sensible ideas. After outside pressure was brought to bear, including by Ms. Bair’s systemic risk council (of which I am a member), there are signs that the S.E.C. will finally at least issue some proposed changes for public comment.

I do not know where Ms. Miller stands on money-market reform; indeed, from her public remarks it is very hard to know precisely where she is on any reform issue. It would be most unfortunate to put her in at the S.E.C. precisely when the mutual-fund industry is about to come in for some serious scrutiny. The optics, as they say in Washington, would not be good.

More broadly, there is a new push for financial reform – even from people who are close to Wall Street. In a wave of speeches and other statements (some you have seen and some you will see soon), voices are being raised against the too-big-to-fail approach and related causes of financial fragility. In particular, a speech last month by Daniel Tarullo, a governor of the Federal Reserve, seems to have released a great deal of pent-up creative thinking within the official sector.

Size caps for big banks are definitely on the drawing board, at least along the lines that Mr. Tarullo identified, which would limit nondeposit liabilities at any one institution relative to the size of our economy.

Given this momentum for responsible reform, does President Obama really want to appoint a financial-services executive – with a nonexistent or weak track record on reform – to a prominent public policy and enforcement position?

As Steven Ramirez has pointed out, Big Finance went all in for Mitt Romney and against Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio and Elizabeth Warren, elected to the Senate in Massachusetts. This was a comprehensive electoral defeat for Wall Street; whenever its behavior was at stake, people voted for change. And their campaign contributions did not seem to produce the outcomes they wanted.

There is a view in Washington that politicians need Wall Street and its money – to start campaigns, to provide a wall of funding at critical moments and to help create a generous endowment for their post-presidential activities. Without a doubt, this has been the pattern in the past.

But in this big country are many diverse business sectors – and lots of people willing to give money without asking for special-interest favors.

Choosing a new chairman of the S.E.C. is the perfect time for President Obama to decide whether, despite everything, to go for the status quo – which brought us to our current economic predicament – and nominate Ms. Miller for the S.E.C. Or does he really want effective change? In that case, he should nominate Mr. Barofsky or someone who can match his stellar qualifications.

An edited version of this post previously appeared on the NYT.com Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

November 21, 2012

Maybe Nate Silver Was Wrong

By James Kwak

I think Nate Silver does a good job aggregating polls to make meaningful quantitative predictions about upcoming elections. But as he said himself shortly before the election, if the polls he relies on are systematically biased, then his forecasts are going to be off.* Many people have noted that Silver (and other quantitative poll aggregators like Sam Wang) correctly predicted an Obama victory and the outcomes in most if not all states.

But the fact remains that Obama did modestly better than the polls, and hence the poll aggregators, expected (not to mention than the Romney campaign expected). We shouldn’t read too much into this, as even where Obama significantly overperformed—like in Iowa, where Silver forecast a 3.2 percentage point victory and the actual came in at 5.7 points—the results were within the confidence intervals. But it’s also possible that the polls really were systematically biased, only they were biased against Obama—not against Romney, as conservative pundits were claiming in the last days.

Why would that be? One possibility is turnout. Many polls incorporate a likely voter model, which weights the sample to try to approximate the expected composition of the electorate. Gallup’s problem, I believe I read somewhere, was that they expected the electorate to be whiter than it turned out to be. In retrospect, we have anecdotal evidence that the electorate was younger and less white than many people (such as Paul Ryan) expected. And one common explanation is that this was due to the strength of the Obama campaign’s get-out-the-vote operation.

One piece of evidence for this theory is that Obama’s performance relative to expectations was especially good in the swing states, where you would expect him to have devoted most of his GOTV efforts.** Of the nine major swing states (in order of competitiveness, according to Silver, Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, Colorado, Iowa, New Hampshire, Ohio, Nevada, and Wisconsin), Obama beat Silver’s poll-based forecast in seven; on average, including the two states where he underperformed, he beat the polls by 1.1 percentage points. Of the other forty-one states and the District of Columbia, by contrast, Obama overperformed in only twenty-three, or just over half, and on average he beat the polls by only 0.4 percentage points.

Now, this is not something that Nate Silver was supposed to predict. Just before the election, his forecast is based almost entirely on the polls. And he freezes his model several months before the election, precisely because he doesn’t want it to be influenced by subjective judgments.

But this is exactly the kind of thing that journalists (and their subspecies known as pundits) are supposed to predict. That Obama would have the best turnout operation ever is not something that Nate Silver could predict in January. But all those people who don’t believe in polls, who think that old-fashioned beat reporting and gut instinct are the way to predict elections, could have done the work to figure out that Obama had the best turnout operation ever. Based on that research, the pundits and the political experts could then have said, “I expect Obama will do better than the polls, because the current generation of likely voter models does not take into account the strength of Obama’s turnout operation.” And that would have added value to what Silver was doing.

In other words, this was an election where old-fashioned reporting and punditry could have provided some insight into the outcome. But they didn’t, because the pundits were too busy spinning false stories about momentum (which were provably false, since momentum does show up in polls) instead of looking for relevant facts.

In theory, poll aggregation should not be the last word in election forecasting; there should be a place for political expertise. But with the “experts” we’ve got now, it is the last word.

* Does anyone know why all posts from the first six days of November have vanished from Silver’s blog?

** You would also expect him to have devoted most of his other efforts in those states, but those activities, such as TV advertising, should have shown up in the polls before Election Day.

November 17, 2012

Neil Barofsky For The S.E.C.

By Simon Johnson

There are two fundamentally different views regarding modern Wall Street. The first is that the financial sector has been terribly and unjustly put upon in recent years – regulated into the ground and treated with repeated disrespect, including by the White House.

There was, for example, an impressive amount of whining this week when no one from a big bank was invited to a high-profile meeting with the president on fiscal issues. As the people holding strongly to this view run large financial institutions and have effective public relations teams, this has become an important part of the conventional or establishment wisdom, repeated without question in some parts of the media.

The second view is that the powerful people who run global megabanks have lost all sense of perspective – including failing to realize that they have more access to people at the top of our political power structures than any other sector has ever had. Anyone who doubts this view – or wonders exactly how the revolving door among politics, lobbying and banking works – should read Jeff Connaughton’s account, “The Payoff: Why Wall Street Always Wins” (which I have written about in more detail before). Mr. Connaughton is most gripping when he describes the failure of law enforcement around securities issues, including issues with both the Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Which of these views is correct? We will soon know, because there is a simple and direct test that is fast approaching: Whom will President Obama nominate as the new chair of the S.E.C.? (Mary Schapiro, the current chairwoman, is widely reported to be stepping down soon.)

There are only two possible outcomes. The president could pick someone who is very close to the securities industry, for example a senior financial services executive or one of their favorite lawyers or someone who already works in their “self-regulatory” apparatus. Any former politician who has taken large donations from Wall Street or an academic who sits on the board of a large financial company would also fit into this category. There is no shortage of candidates from this side of the contest.

Alternatively, the president could choose someone who is not only willing to enforce the law and regulation but who would actively seek to change the conventional wisdom around finance. For example, all too often we hear – including from some top officials – that if we relax the capital requirements, the economy will grow faster in a sustainable manner.

This is a very dangerous idea that completely ignores the fact that Europe went much farther than we did in reducing bank capital in the run-up to 2008 (i.e., allowing banks to finance themselves with more debt and less equity) and that this directly contributed to the complete disaster they now face. Thank goodness that Sheila Bair, then head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and a few others successfully resisted attempts to lower bank capital in a parallel manner in the United States. (If you want more detail on these points, look at Ms. Bair’s book, Bull by the Horns, or the forthcoming book by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig, “The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong With Banking and What to Do About It.”)

Without doubt, part of the problem that led to the crisis of 2008 was weak regulation. But can any regulation be effective at any moment the conventional wisdom is that we have some form of “new economy” in which asset prices can only go up – and therefore financial institutions should be allowed to borrow a great deal more relative to their shareholder equity?

To make Wall Street safer – and more helpful to the rest of the economy – implementing new rules is not enough. We need completely new thinking about securities markets, including all dimensions of how investors are treated and where financial-system risks lurk. We must be able to trust the financial system again – and we are currently a long way from this point.

There are three potential S.E.C. chairmen who could have this kind of impact. If you have other names, see if they match these three in terms of integrity, willingness to go against the consensus and ability to get things done.

First, former Senator Ted Kaufman of Delaware has been a consistent advocate for financial-sector reform and was one of the clearest voices during the 2010 legislative process that led to Dodd-Frank. His advice was ignored then; in fact he was opposed directly by Treasury and the White House (see Mr. Connaughton’s book for details). It is not too late for the president to change his mind. (See this longer piece I did a few days ago on Senator Kaufman for this Boston Globe feature.)

Second, Neil Barofsky is the former special inspector general in charge of oversight for the Troubled Asset Relief Program. A career prosecutor, Mr. Barofsky tangled with the Treasury officials in charge of handing out support for big banks while also failing to hold the same banks accountable, for example in how they treated homeowners. He confronted these powerful interests and their political allies repeatedly and on all the relevant details – both behind closed doors and in his compelling account, published this summer: “Bailout: An Inside Account of How Washington Abandoned Main Street While Rescuing Wall Street.”

His book describes in detail a frustration with the timidity and lack of sophistication in law enforcement’s approach to complex frauds. He could instantly remedy that if appointed — Mr. Barofsky is more than capable of standing up to Wall Street in an appropriate manner. He has enjoyed strong bipartisan support in the past and could be confirmed by the Senate (just as he was previously confirmed to his TARP position).

Third, Dennis Kelleher is a former senior Senate leadership aide with a great deal of political experience, including during the financial crisis and in the negotiations that led to Dodd-Frank, and now runs the pro-reform group Better Markets. Previously, Mr. Kelleher was a partner at the international law firm of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, where he specialized in the S.E.C., securities, financial markets and corporate conduct in the US and Europe. No one has been a more effective advocate of implementing substantive reforms. Mr. Kelleher and his team are in the trenches every day, arguing on behalf of taxpayers and ordinary citizens at every opportunity before the entire range of regulators, in court cases and with Congress and the administration. They are also amazingly effective – particularly considering the huge resources of the firms that they go up against (for some examples, see this New York Times profile of Mr. Kelleher). His private and public sector experience and expertise are very highly regarded throughout the financial regulatory agencies and in the legislative and executive branches more broadly. He also has strong relationships on both sides of the aisle and could likely be confirmed.

At the start of this second presidential term, many people are optimistic that President Obama will finally push hard for meaningful change around Wall Street – including at the S.E.C.

Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup were all big donors to the Obama campaign in 2008 (see this recent column by William D. Cohan), but they did not make the top 10 list this year. Now would be a perfect time for the president to clean up Wall Street with a strong S.E.C. that is focused on enforcing the law and overturning dangerous parts of the conventional wisdom.

An edited version of this post appeared on the NYT.com’s Economix blog on Thursday; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire post, please contact the New York Times.

November 14, 2012

I’m Betting on Grover

In the wake of their overwhelming defeat last week (at least relative to expectations a few months ago), Republicans are wondering how to improve their position in the next election. John Boehner has apparently told his caucus to “get in line” and support negotiations with the president over the “fiscal cliff” and the national debt. More shockingly, The Hill reported rumblings that Grover Norquist’s stranglehold over tax policy may be weakening, with one Democratic aide even saying, “As far as [Norquist’s] ability to sway votes, it’s gone.” Norquist’s Taxpayer Protection Pledge forbids lawmakers from voting for legislation that would either raise tax rates or increase tax revenues; if Republicans are questioning the pledge, that might pave the way for a bipartisan compromise to increase taxes.

Norquist’s response: “Nobody’s actually broken the pledge. That doesn’t keep me up at night.” He’s right not to worry. He has history on his side.

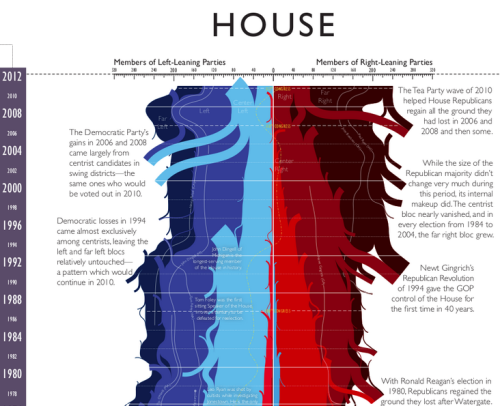

Let’s take a brief look at American political history since the 1970s, courtesy of the incomparable xkcd:

That picture shows the composition of the House of Representatives from the late 1970s to the 2010 election. (The full picture goes all the way back to 1789.) The colors indicate ideological positions as measured by DW-NOMINATE scores. Bright red is center-right, medium red is right, and dark red is far right. The major pipes feeding in from the right are net increases resulting from elections: note for example the wave elections of 1994 and 2010.

The modern conservative movement was founded on a marriage of principle and pragmatism. Back in the 1980s, Newt Gingrich realized that ideological purity could be a winning political strategy: by holding out for small government and low taxes, he attracted far-right groups that had been ignored by both parties for decades as well as rich donors who were looking for a new place to invest their money. His fundraising prowess, organizational discipline, cultivation of talk radio, and networking with grass-roots conservative groups made possible the Republican sweep of 1994. Over the next decade, the increasing influence of key conservative power brokers continued the purge of moderate Republicans and their replacement by extremists (note the disappearance of the bright red). (For the full story, see chapter 3 of White House Burning.)

But the key thing to note is what happened when the conservatives lost, notably in 2006 and 2008. One possible response would have been to realize that the party had become too extreme and tack back toward the center. We know that didn’t happen, as illustrated by the dark red influx of 2010. Between principle and pragmatism, Republicans chose principle.

Why do Republicans behave this way? There are many reasons. The funding that they need to win elections comes largely from a small number of extremely conservative power brokers such as the Koch brothers. Widespread gerrymandering means that elections are settled at the primary stage, where the power of far-right groups (Club for Growth, Americans for Prosperity, FreedomWorks, etc.) places a premium on ideological purity. (For whatever reason, the trend toward the extreme has been much weaker among Democrats.)

The anti-tax platform also possesses a self-reinforcing simplicity. The vision of small government and lower taxes is clear and compelling in the abstract (even if it could be devastating in practice). The “no new taxes” pledge is trivially easy to monitor and, once broken, provides a convenient bludgeon for a primary opponent to use. It’s not a position that easily accommodates compromise.

Finally, if you take the long view, there’s no reason for conservatives to back away from their absolutist anti-tax stance. So they lose an election or two. What happens? When it comes to taxes, Democratic majorities at best hold the line against further tax cuts. After their sweep in 2008, President Obama and his congressional allies passed a couple of modest tax increases to pay for Obamacare (and one of those, the excise tax on Cadillac plans, is one that conservative economists profess to like), but also extended the Bush tax cuts and added a few more tax cuts of their own; now Obama wants to make more than 80 percent of the Bush tax cuts permanent, and last summer he offered up his own proposals for entitlement cuts. When the Republicans return to power, as they inevitably will, they can just pick up where they left off.

Sure, some Republicans will say that they don’t take orders from Grover Norquist. But for the last eighteen years, the hardline anti-tax position has been a huge winner for Republicans. Given that Democrats have shown exactly zero ability to punish them for it, I can’t see any reason why they should change their ways now.

If there is some sort of compromise in the next couple of months, it’s going to be one that Republicans can frame as a tax cut, not an out-and-out violation of the Grover pledge; one scenario is that the year ends with no deal, tax rates go up, and then Obama and the Republicans agree to cut them. Because at the end of the day, Peter Steiner is still right.

November 13, 2012

If Entitlement Programs Are Your Top Priority, the Fiscal Cliff Is Your Friend

By James Kwak

There is a lot of low-grade confusion in reporting on the fiscal cliff, primarily because most articles discuss two distinct problems: (a) the contractionary impact of automatic tax increases and spending cuts that go into effect on January 1 and (b) the large and growing national debt—often without clearly distinguishing between them. In fact, (a) and (b) go in opposite directions. Any deal that solves (a) will only make (b) worse; if you really only care about (b), you should be happy about (a). (Instead, Republicans who claim to care only about (b) are squawking about (a) because they want to preserve the Bush tax cuts.) Most reporters understand this and don’t make the obvious mistake of equating the fiscal cliff to the debt problem, but the two are juxtaposed so often they risk blurring into each other.

So, for example, the Washington Post published an article titled “Liberal groups mobilize for ‘fiscal cliff’ fight over Social Security, Medicare.” (As an aside, when did capitalization in titles become optional?) The facts in the article are fine, but you still could get the impression that the fiscal cliff poses a threat to Social Security and Medicare.

Just the opposite is true. If your top priority is the preservation of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid for the long term, then the fiscal cliff is the best thing that ever happened.

First, the expiration of the Bush-Obama tax cuts will, on its own, eliminate roughly half of the long-term gap between federal government revenues and expenses.* Higher tax revenues (raised through the individual income tax, which is the most progressive part of the tax code) will reduce the pressure to do something about entitlement spending—at least the pressure that is due to budgetary constraints, not the pressure that is due to ideological opposition to those programs.

Second, the automatic sequesters mandated by the Budget Control Act of 2011 barely touch the major entitlement programs. Social Security and Medicaid are specifically exempted; most Medicare spending cuts are limited to 2 percent. That means that the rest of the government gets smaller, again reducing budgetary pressure on these crucial programs.

Now, if you are the kind of person who cares about social insurance programs, you probably also care about unemployment, and you may legitimately worry that tax increases and spending cuts will hurt the economy and reduce jobs. You may be torn between two objectives: preserving social insurance programs for the long term and reducing unemployment in the short term. But you have to recognize that the fiscal cliff is unambiguously good for those social insurance programs. Otherwise you’re not making sense.

* For the estimates, see White House Burning, pp. 182–83.

November 12, 2012

Be Happy, Eat Fruits and Vegetables

By James Kwak

From the treasure trove that is the NBER working paper series, a friend forwarded me “Is Psychological Well-Being Linked to the Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables?” by David Blanchflower, Andrew Oswald, and Sarah Stewart-Brown (NBER subscription required). It got some media attention last month when the paper first came out, but I wanted to read it because, well, I eat a lot of fruits and vegetables: I generally aim for seven servings a day, although when life is busy it can be as low as three or four. (Right now I’m munching on dried mango slices.)

The core of the paper is a bunch of regressions that show that better psychological well-being (which is all the rage these days) is correlated with eating more fruits and vegetables, with benefits up to at least five servings and in some cases up to eight servings. This isn’t particularly surprising on its face, since eating fruits and vegetables is probably correlated with having a high income, exercising, being fit, cooking, and any number of other things that are conducive to happiness.

But the relationship persists even when you control not for the usual things—age, gender, race, marital status, income—but even when you control for things like education, religion, health status, body mass index, smoking, sexual activity, exercise, marital status, number of children, disability status, and employment status. (See Table 1, column 3.) This is surprising, at least to me, since it says that fruits and vegetables make you happy in some way other than making you healthier and more fit.

It’s still quite possible that the mechanism at work isn’t the fruits and vegetables themselves but something else that correlates with consumption of fruits and vegetables. I suspect that people who eat fruits and vegetables tend to be those with more time on their hands (even within the group of employed people) and who put more effort into taking care of themselves. But just in case it is the fruits and vegetables themselves, go eat an extra apple or banana. We already know that eating less meat is good for the environment, anyway.

Some Things Don’t Change

By James Kwak

Which of these things doesn’t belong? John Boehner: “The year 2013 should be the year we begin to solve our country’s debt problem through entitlement reform and a new tax code with fewer loopholes and lower rates.”

Can you imagine Bill Belichick (or any other football coach) saying, “This should be the year we win more games by giving up fewer yards on defense and improving our offense by reducing turnovers and gaining fewer yards per play”?

As long as Republicans persist in claiming to believe that lower tax rates will reduce deficits, nothing in Washington will change. Given their ability to deny both climate change and evolution, denying simple budgetary arithmetic is trivially easy.

November 8, 2012

The Importance Of Elizabeth Warren

By Simon Johnson

One of the most important results on Tuesday was the election of Elizabeth Warren as United States senator for Massachusetts. Her victory matters not only because it helps the Democrats keep control of the Senate but because Ms. Warren has a proven track record of speaking truth to authority on financial issues – both to officials in Washington and to powerful people on Wall Street.

During the campaign, Ms. Warren’s opponent and his allies made repeated attempts to portray her as antibusiness. In the most bizarre episode, Karl Rove’s Crossroads GPS ran an ad that contended that she favored bailing out large Wall Street banks. All of this was misdirection and disinformation.

Ms. Warren has long stood for transparency and accountability. She has insisted that consumers need protection relative to financial products – when the customer cannot understand what is really on offer, this encourages bad behavior by some companies. If this behavior spreads sufficiently, the entire market can become contaminated – damaging the entire macroeconomy, exactly as we have seen in the last decade.

Honest bankers should welcome transparency in all its forms. And the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which Ms. Warren helped to establish, has made major steps in this direction. Ms. Warren has strong support from the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, and her pushback against sharp practices by big banks resonates across the political spectrum. (Disclosure: James Kwak and I wrote positively about Ms. Warren and her approach in “13 Bankers.”)

She has also established an impressive track record for effective oversight in Washington. As the chairwoman of the Congressional Oversight Panel for the Troubled Asset Relief Program, she drew bipartisan praise (until, of course, she decided to run for public office).

How much can a new senator accomplish? Within hours of her victory, some commentators from the financial sector suggested that no freshman senator can achieve much.

This is wishful thinking on their part. A newly elected senator can have a great deal of impact if she is well informed on relevant details, plugged into the policy community and focused on a few key issues. It also helps if such a senator can bring effective outside pressure to bear – and Ms. Warren is a most effective communicator, including on television. She has an unusual ability to cut through technical details and to explain the issues in a way that everyone can relate to.

Ms. Warren is a natural ally for Senators Sherrod Brown of Ohio, Jeff Merkley of Oregon, Carl Levin of Michigan, Jack Reed of Rhode Island and other sensible voices on financial-sector issues (including some on the Republican side who have begun to speak out). My expectation is that Ms. Warren will work effectively across the aisle on financial-sector issues without compromising her principles – and this could really be productive in the Senate context.

Hopefully, Ms. Warren will get a seat on the Senate Banking Committee, where at least one Democratic slot is open.

President Obama should now listen to her advice. Senator Warren should have been appointed head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2010 – but was opposed by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner. Unfortunately, the president was unwilling to override Treasury.

If President Obama wants to have impact with his second term, he needs to stand up to the too-big-to-fail banks on Wall Street.

The consensus among policymakers has shifted since 2010, becoming much more concerned about the dangers posed by global megabanks; that has been clear in recent speeches by the Federal Reserve governor Daniel Tarullo; Richard Fisher, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, and Andrew Haldane of the Bank of England (all of which I have covered in this space – including last week).

At the same time, we should expect a renewed pushback against all recent attempts at financial-sector reform – a point made by American Banker, a trade publication, immediately after the reelection of President Obama.

Scandals of various kinds will be thrown into this mix. The full extent of money-laundering at HSBC is only now becoming apparent. Complicity of various institutions in rigging the Libor should also become clearer in coming months. No doubt there will be big unexpected trading losses somewhere in the global banking community. The European macroeconomic and financial situation continues to spiral out of control.

Senator Warren is well placed, not just to play a role in strengthening congressional oversight but in terms of helping her colleagues think through what we really need to make our financial system more stable.

We need a new approach to regulation more generally – and not just for banking. We should aim to simplify and to make matters more transparent, exactly along Senator Warren’s general lines.

We should confront excessive market power, irrespective of the form that it takes. We need a new trust-busting moment. And this requires elected officials willing and able to stand up to concentrated and powerful corporate interests. Empower the consumer – and figure out how this can get you elected.

Agree with the people of Massachusetts, and give Elizabeth Warren every opportunity.

An edited version of this post appeared this morning on the NYT.com’s Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers