Simon Johnson's Blog, page 32

October 23, 2012

Financial Lobby: Stupid or Disingenuous? You Decide

By James Kwak

Courtesy of Matt Yglesias, from the Financial Services Forum:

“We write today to urge you to work together to reach a bipartisan agreement to avoid the approaching ‘fiscal cliff,’ and take concrete steps to restore the United States’ long-term fiscal footing.”

And later:

“But merely avoiding the fiscal cliff is not enough. We further urge you and your colleagues to enact legislation that truly restores the nation’s long-term fiscal soundness.”

It’s too obvious to waste more than a sentence spelling out what’s wrong here, so here it is: “Going over” the “fiscal cliff” is the single best thing we could do to “restore the United States’ long-term fiscal footing.” The CEOs of every big bank (who signed the letter) must know that. Right?

There are valid arguments against going over the fiscal cliff, but the national debt is not one of them. Going over the cliff would do more to address the long-term debt than anything any politician has proposed. And, as Yglesias points out, “If you care about inequality, jumping off the cliff offers by far the best chance for addressing it,” since it is the only plausible way to significantly increase taxes on the wealthy.

Why Reading the Front Page of the Newspaper Makes You Stupider

By James Kwak

At least when it comes to statistical issues:

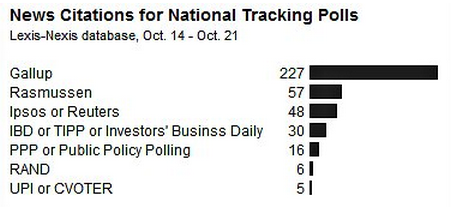

(Courtesy of Nate Silver.) Gallup is the huge outlier among the tracking polls, which shows Romney leading by 6–7 points. (On average, the national polls show an exactly tied race.)

This news is a few days old, but the general principle it illustrates is timeless. Reporting tends toward the dramatic and the surprising. In some cases, that’s probably fine—like if you read the paper for entertainment. When it comes to statistics that suffer from measurement error, it’s journalistic malpractice.

October 22, 2012

Revolving Doors Matter

By James Kwak

It is common fare for people like me to point disapprovingly to the revolving door between business and government, which ensures that every Treasury Department is well stocked with representatives of Goldman Sachs. In 13 Bankers, the revolving door was one of the three major channels through which the financial sector influenced government policy, alongside campaign contributions and the ideology of finance. The counterargument comes in various forms: people like Robert Rubin and Henry Paulson are dedicated civil servants who wouldn’t favor their firms or their industries, the government needs people with appropriate industry experience, etc.

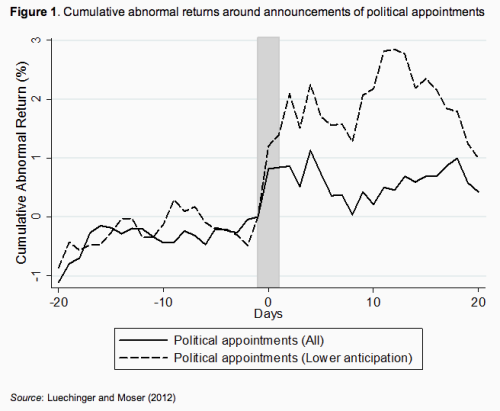

It is certainly possible that industry experts provide valuable skills and experience to the government. But that value comes with a cost; put another way, it’s not just the public good that benefits. Using data on Defense Department appointments, Simon Luechinger and Christoph Moser (paper; Vox summary) measured the impact of political appointments on the stock market valuation of appointees’ former firms; they also measured the impact on firms’ stock market valuations of hiring a former government official. In both cases, the stock market reacted positively to new turns of the revolving door. Here’s the chart for political appointments:

Luechinger and Moser survey the existing literature on the value of political connections in the first part of their paper. To summarize, this is the kind of thing that you expect to find in developing countries and countries with weak institutions—not in the United States, the paragon of democracy and the greatness we never weren’t.

This research touches on one of the most important questions of our time: whether, in our age of extreme and increasing inequality, public policy has become the private preserve of the rich and the well-connected. In Why Nations Fail, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson described the importance of inclusive political institutions for economic development. Although the United States became rich and powerful in large part because of our inclusive institutions, it is possible for an elite to shut down those institutions in order to further their economic interests, as occurred in late-medieval Venice. (For a summary, see my review of the book in Democracy.)

The disproportionate influence of economic elites on political decision-making is a hallmark of emerging market crises; its importance in the United States during the financial crisis was a central theme of “The Quiet Coup” and 13 Bankers. Luechinger and Moser provide a little more evidence that we are a bit more like Indonesia of Suharto than we might care to admit.

October 17, 2012

Bobbing and Weaving

By James Kwak

Mitt Romney’s latest attempt to make his tax plan seem plausible (that is to say, not a pack of blatant lies) is the idea of capping deductions at some level, like $17,000 or $25,000. Of course, as we all know, it doesn’t add up; Dylan Matthews provides a quick summary. If you cap deductions and you cut rates by 20 percent, everyone’s taxes go down, and the very rich (but not the super-super-rich) benefit the most.

This shouldn’t be news to anyone, because this problem has already been solved in its general form: there’s no way his numbers add up, because you could eliminate all the tax breaks for the rich and still not pay for a 20 percent rate cut. I confess I have some attachment to this issue because I think I was one of the first people to point out the mathematical impossibility of the Romney tax plan (the day after he announced the 20 percent rate cut).

Unfortunately, of course, this is all about politics, and arithmetic coherence is not the bar Romney needs to clear. He just needs to get enough undecided voters (stop and think for a second about what it means to be undecided right now) to think that his tax plan isn’t a complete fraud and to think that all of us self-appointed defenders-of-math are just Obama hacks. And this latest cap on deductions is probably enough to clear that much lower bar.

October 16, 2012

Luck, Wealth, and Richard Posner

By James Kwak

I disagree with Richard Posner—the old Richard Posner behind the law and economics movement—on so many things that I always worry when he seems to agree with me. Did I do write something stupid? I wonder.

A friend forwarded me Posner’s latest blog post, “Luck, Wealth, and Implications for Policy,” parts of which sound vaguely like a post I wrote three years ago, “Do Smart, Hard-Working People Deserve To Make More Money?“* In that post, I argued that even if differences in incomes are due to things that people ordinarily think of as “merit,” like intelligence and hard work, that doesn’t mean that rich people have a moral entitlement to their wealth, because they didn’t do anything to deserve their intelligence or their propensity to work hard. In summary, “I have little patience for the idea that rich people deserve what they have because they worked for it. It’s just a question of how far back you are willing to acknowledge that chance enters the equation.”

Posner now goes even further than I did: “I think that ultimately everything is attributable to luck, good or bad,” he writes, including the propensity for working hard, a low discount rate, and so on. “In short, I do not believe in free will. I think that everything that a person does is caused by something. . . . If this is right, a brilliant wealthy person like Bill Gates is not ‘entitled’ to his wealth in some moral, Ayn Randian sense.”

He goes on—he is still Richard Posner, after all—to argue that tax policy should be concerned solely with incentive effects. High taxes on the wealthy are not unfair in any meaningful sense, and it is meaningless to say that rich people pay a disproportionate share of their income in taxes, absent some incentive-based argument. It does make sense to tax inherited wealth more than earned income, because of the incentives it creates. The same goes for investment profits, either because they are the product of luck (in the ordinary sense) or because people with lots of money are going to invest it anyway rather than consuming it all in the current period.

But I don’t think it’s quite right to say that tax policy should be entirely utilitarian. Right now, our country faces large federal government deficits, the prospect of growing spending on social insurance programs, and sorely inadequate expenditures on infrastructure and the safety net. To fix those problems, money has to come from somewhere. If rich people don’t have any particular moral entitlement to their wealth because that wealth is the product of luck in one form or another, isn’t it obvious that they should pay more in taxes than poor and middle-class people? Imagine three people stranded on a desert island and a genie that gives one person ten coconuts, the second person two coconuts, and the third zero coconuts. Who should share with the third person: the first or the second? You can get the same result by looking at the marginal utility of wealth, à la Diamond and Saez.

Now redistribution can go too far because of the incentive effects, but that doesn’t mean that redistribution is not an appropriate objective of the tax system. It just means that it has to be balanced against incentive considerations. There is a moral dimension to tax policy (although Diamond and Saez would call it part of utility maximization). It’s just the opposite of what Paul Ryan thinks it is.

* Of course, I’m not saying that Posner is copying my ideas, since (a) there’s virtually no chance that he knows who I am and (b) the ideas in that post, like most of my ideas, are pretty obvious.

October 12, 2012

Why Taxes Should Pay for Health Care

By James Kwak

William Baumol and some co-authors recently published a new book on what is widely known as “Baumol’s cost disease.” This is something that Simon wanted to include in White House Burning, but I couldn’t find a good way to fit it in (and it would have gone in one of the chapter’s I was writing), so I it isn’t in there. (Baumol is cited for something else.) But in retrospect, I should have put it in.

Baumol’s argument, somewhat simplified, goes like this: Over time, average productivity in the economy rises. In some industries, automation and technology make productivity rise rapidly, producing higher real wages (because a single person can make a lot more stuff). But by definition, there most be some industries where productivity rises more slowly than the average. The classic example has been live classical music: it takes exactly as many person-hours to play a Mozart quartet today as it did two hundred years ago. You might be able to make a counterargument about the impact of recorded music, but the general point still holds. One widely cited example is education, where class sizes have stayed roughly constant for decades (and many educators think they should be smaller, not larger). Another is health care, where technology has vastly increased the number of possible treatments, but there is no getting around the need for in-person doctors and nurses.

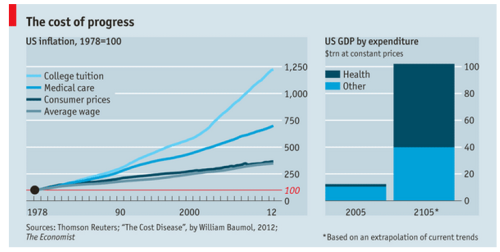

The problem is that in those industries with slow productivity growth, real wages also have to rise; otherwise you couldn’t attract people to become classical musicians, teachers, or nurses. Since costs are rising faster than productivity, prices have to rise in real terms. Note that university tuition and health care costs are both going up much faster than overall inflation. As a consequence, since GDP is measured in terms of prices paid, these sectors take up a growing share of GDP, just as health care is doing throughout the developed world.

But in Baumol’s formulation, that’s just fine. To see why, consider this figure from the Economist’s review of the book:

Look at the right-hand panel. The point is that if you extrapolate from current trends, health care will be a ridiculous proportion of the economy a century from now, even if we do nothing to slow its rate of growth; but because of productivity increases, the non-health care sector will still be much bigger than it is today, so we will still be much better off than today in aggregate.*

Look at the right-hand panel. The point is that if you extrapolate from current trends, health care will be a ridiculous proportion of the economy a century from now, even if we do nothing to slow its rate of growth; but because of productivity increases, the non-health care sector will still be much bigger than it is today, so we will still be much better off than today in aggregate.*

But that doesn’t mean that everything is fine and dandy. Unlike a lot of things in the light blue portion of that chart, health care is a necessity. If 60 percent of the economy is health care, health care will be a much larger share of the average family’s budget than it is today; and if it’s a huge share of the average family’s budget, then many families with below-average incomes won’t be able to afford it.

This is the basic problem with market-based approaches to our health care problem: in a free market, poor people won’t get any, and middle-class people won’t get very much. Baumol is right that in the aggregate our society will be able to pay for all the health care we need, and plenty of other stuff besides; but with our current level of inequality, many actual families won’t be able to get the care they need.

Now, Baumol himself realizes this. One corollary of Baumol’s cost disease is that as low-productivity sectors get relatively more expensive, it gets harder and harder to make a profit, so they tend to get taken over by the government. Again, consider health care and education. (Classical music, which cannot make a profit but is not a necessity—much as I love it—has instead been taken over by private charity.) And this is just the way it should be: Everyone needs health care, but the law of productivity increases dictates that it gets more and more expensive, so the only sane solution is to keep prices at an affordable level and let the government bear the losses. And by “bear the losses,” I mean distribute them to taxpayers (since there is no entity called “the government” that exists in isolation from the people) through a progressive tax system.

Guess what? That’s what Medicare does today. (The Medicare payroll tax isn’t progressive, but most of Parts B and D are funded through general revenues, which mainly come from the individual income tax.) By contrast, Romney-Ryan Vouchercare, by capping the growth rate of benefits at an artificially low level, shifts the growing stack of health care costs (dark blue in the chart) directly onto families, many of whom won’t be able to afford it. Vouchercare is an attempt to rein in health care costs through sheer force of will. It won’t work. It can’t work.

This was, in essence, one of the key arguments of White House Burning: health care costs are going to be what they are going to be, and we can pay for them. Yes we can. We can pay for them because we have plenty of room to raise taxes in all sorts of non-distorting or distortion-reducing ways. We can pay for them because productivity increases mean that, in aggregate, our after-tax real income is still going up. This means that tax revenues will grow as a share of the economy, but as Baumol’s cost disease implies, they should rise as a share of the economy. Comparing tax revenues today to tax revenues in a distant past when health care costs were much lower is just not relevant.

* That chart isn’t per capita, but eyeballing it it looks like a fourfold increase in non-health care GDP; with U.S. population growing at a little less than 1 percent, that’s still a big increase in per capita non-health care GDP.

October 11, 2012

Read This Book, Win The Election

By Simon Johnson

With the presidential election looming and both sides looking for a knockout blow in the vice-presidential debate on Thursday evening, now is a good time for both Democrats and Republicans to look for one more defining issue. The new book by Sheila Bair, “Bull by the Horns: Fighting to Save Main Street From Wall Street and Wall Street From Itself,” offers exactly that – to whichever party is smart enough and fast enough to take up the opportunity.

Ms. Bair lays out a compelling vision for both financial-sector reform and for dealing with the continuing mess around mortgages. Neither presidential campaign is likely to endorse her ideas in all their specifics. But if a candidate signaled that he had read and understood the main messages in this book, this would have great appeal both with undecided centrist votes and – importantly – with their respective bases.

Ms. Bair was chairwoman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation from June 2006 until July 2011. In that position, she had a seat at the table for all the big decisions during the financial crisis of 2007-9, and she was also an important player during the financial reform negotiations of 2009-10, leading up to the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010.

(Disclosure: I’m a member of the nongovernmental Systemic Risk Council that Ms. Bair created and leads; I was also appointed to the F.D.I.C.’s Systemic Resolution Advisory Committee while Ms. Bair was still chairwoman.)

Ms. Bair, a Republican from Kansas, worked with Bob Dole and was appointed to the F.D.I.C. by President George W. Bush. Her defining positions were against the interests of the very largest financial institutions.

And her biggest confrontations were with Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, the former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and – according to Ms. Bair – someone who continually favored the largest banks and their profitability in the mistaken view that this would serve the broader social interest in financial stability and sustained economic prosperity.

During the height of the financial crisis, Mr. Geithner wanted at various times to commit more taxpayer resources with fewer conditions to support very large banks, including allowing them to pay very large bonuses to executives. Ms. Bair was consistently on the side of wanting more strings attached – the point being that these financial institutions had managed themselves into great trouble. As she notes on Page 363:

“An institution that is profitable is not necessarily one that is safe and sound or one that is serving the public interest. All of the large financial institutions were profitable in the years leading up to the crisis, but they were making big profits by taking big risks that ultimately exploded in their – and our – faces.”

Ms. Bair’s point was not about any kind of retribution but rather that the long experience of the F.D.I.C. indicates that the best time to clean up any financial sector mess is at the moment and point of intervention. Because it has insured small depositors – the public – since the 1930s, the F.D.I.C. has developed a well-informed approach to failing banks. It works long and hard to ensure that depositor protection works – and it does – without imposing costs on the taxpayer.

When I worked at the International Monetary Fund during 2004-6 and 2007-8, we regarded the F.D.I.C. as carrying out best practice in the world with regard to how to handle failing banks.

In Ms. Bair’s persuasive account, both the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations were primarily focused on protecting the large banks. Both administrations consistently ignored the relationship between the need to fix our bloated, free-wheeling financial sector and sustaining our broader economic prosperity. And both administrations paid insufficient attention to the persistent problem of mortgages.

In most financial crises, there is some form of “debt overhang” problem – meaning that the economy cannot fully get back on its feet until loans are written down, typically through some form of bankruptcy or negotiated restructuring process. Some of the most fascinating details in “Bull by the Horns” concern instances when Ms. Bair and her F.D.I.C. colleagues proposed various ways to deal with mortgages, only to be shot down or undermined by Mr. Geithner and his colleagues at Treasury (see, for example, Chapter 21).

Judging from the most recent presidential debate, the candidates are still not drawing the link from stable finance to economic prosperity, and they are offering no ideas on how to restructure mortgages.

As new cases are brought against big banks for their mortgage-lending practices – including JPMorgan Chase (for activities of Bear Stearns, which it acquired in 2008) and, this week, Wells Fargo – policy thinking increasingly must grapple with how to structure a potential “global settlement” on mortgages.

Hopefully, Ms. Bair will have a seat at that table; most of the workable ideas are already articulated in her book. More broadly, her policy suggestions are simple and obvious, such as: putting tougher limits on the ability of large financial institutions to take risks with borrowed money; requiring those who securitize mortgages to retain risk if the mortgages later default; and breaking up institutions which are so large and interconnected that they cannot be resolved in bankruptcy without causing wider damage to our economy.

Ms. Bair’s messages and common sense have appeal across the American political spectrum. The right wants an end to implicit government subsidies for large financial institutions. The left wants to curtail the power of global megabanks. Independents want Wall Street to have less political sway in Washington. These are all reasonable and responsible requests.

Either Mr. Romney or Mr. Obama could seize upon the themes in Ms. Bair’s book, craft these into political language and hammer home the substance in the concluding weeks of the campaign.

Or they could just quote the final paragraph of the book:

“Life goes on, as Robert Frost observed. But financial abuse and misconduct don’t have to. Tell the powers in Washington that you want these problems fixed, you want them fixed now and that you will hold all incumbents accountable until the job is done.”

An edited version of this post appeared on the NYT.com’s Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

October 9, 2012

43.4 = 30.9?

By James Kwak

Adam Davidson wrote his latest New York Times Magazine column about how Barack Obama and Mitt Romney largely agree on economic questions. This is a classic example of how to mislead through deceptively selective citation.

Here’s the core assertion:

For someone who lived in the first 150 years or so of this country, it might be hard to see what’s so different about the economic policies of Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. Romney seeks a 25 percent top corporate tax rate, and Obama is proposing 28 percent. Romney wants to eliminate capital-gains taxes for the typical investor and leave the rate at 15 percent for higher earners. Obama wants to increase it to 20 percent. They differ on how to tax the highest incomes. But for most Americans, the distinctions might be mistaken for a rounding error. Both men strongly support expanding free trade and maintaining close to the same level of Social Security and welfare benefits.

As anyone who follows fiscal policy knows, the corporate tax rate is a sideshow. It’s the individual income tax and payroll taxes that bring in the big dollars, and it’s the individual income tax that has the real impact (or not) on inequality.

Mitt Romney wants to lower the top individual tax rate to 28 percent; Obama wants to let it increase to 39.6 percent. When you add in the Medicare payroll tax, Romney’s rate increases to 30.9 percent, while Obama’s increases to 43.4 percent. (Romney wants to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which would mean repealing the 0.9 percent Medicare surcharge on high-income households.) That means Obama’s tax rate would be 40 percent higher than Romney’s. That’s a rounding error?

What about capital gains taxes? Davidson says the difference is between 15 percent and 20 percent. But the Affordable Care Act imposes a Medicare tax on investment income of 3.8 percent for high earners (which, again, Romney would repeal), so the real difference is between 15 percent at 23.8 percent; Obama’s proposed tax rate is 59 percent higher than Romney’s. That’s not a significant difference?

Davidson cites agreement on Social Security and welfare. Social Security, yes, at least for now, since Romney doesn’t want to touch that rail. (His running mate, by contrast, has supported privatization in the past.) I’m not sure what he means by “welfare,” but he certainly can’t mean Medicaid, the largest anti-poverty program. Romney wants to convert Medicaid into a block grant, which in itself would have major impacts on poor people in states that, well, don’t want to help poor people. More importantly, Romney would limit growth in the size of Medicaid grants to inflation plus one percentage point, which is far less than actual health care inflation. So relative to current policy, Medicaid spending would be much lower under Romney—$1.3 trillion over nine years, according to Bloomberg. And, again, Romney wants to repeal the ACA, which includes an expansion Medicaid spending in order to increase coverage. Those all seem like big differences to me.

Finally, Davidson conveniently neglects to mention Medicare, where the differences between the candidates are greatest. Obama wants to maintain the basic structure of Medicare, where benefits are a percentage of real health care costs. Romney wants to change Medicare to a voucher program, where the growth rate of benefits is capped regardless of the growth of actual health care costs. (Obama also wants to reduce the growth rate of benefits, but that’s a target, not a cap; he isn’t proposing a change to the benefit structure.) First of all, these proposals vastly differ in the role of the private sector and how they expect to control health care costs. Even leaving that aside, however, they fundamentally differ in who bears the risk of health care inflation. Obama leaves it with Medicare, hence the federal government; Romney shifts it to individuals.

In short, there isn’t a baldly incorrect fact in the passage from Davidson’s column above, but it’s hard to see how it could be more misleading. There are huge differences between Obama and Romney when it comes to taxes and social insurance programs, and they are sitting out there for anyone to see.

I used to like Planet Money, and many of its reporting-based episodes are still excellent. But ever since the health care debates, I’ve become more and more tired of its tone of cute, isn’t-this-fascinating contrarianism. I generally avoid criticizing them because I like the people there whom I met and because they are affiliated with This American Life, my favorite show in any medium, so I give them the benefit of the doubt. But this column epitomizes everything that is wrong with the journalistic, “tell me a story” approach to economics and public policy: looking for an original angle to take through well-trodden terrain, thumbing your nose at the conventional wisdom, and backing it up with correct but incomplete facts. Sometimes the conventional wisdom is right.

File Under Fascinating

By James Kwak

A reader pointed me to “Instability and Concentration in the Distribution of Wealth,” a paper by Ricardo and Robert Fernholz (Vox summary here). It’s a pretty mathematical paper (and I’m not just talking about the usual multivariate regression here), and I didn’t make it through all the equations. But the basic idea is to come up with a model that might explain the high degree of income and wealth inequality we see in advanced economies and particularly in the United States, where 1 percent of the population holds 33 percent of all wealth.

What’s fascinating is that the model assumes that all households are identical with respect to patience (consumption decisions) and skill (earnings ability). Household outcomes differ solely because they have idiosyncratic investment opportunities—that is, they can’t invest in the market, only in things like privately-held businesses or unique pieces of real estate. Yet when you simulate the model, you see an increasing share of wealth finding its way into fewer and fewer hands:

As the authors emphasize, “it is luck alone – in the form of high realised random investment returns – that generates this extreme divergence.” In the absence of redistribution, either explicit or implicit, this is the kind of society you end up with.

Obviously this isn’t a complete explanation of the high and increasing degree of inequality in American society today. People are not equal in their earning ability, for one. But you could view the variance in career outcomes—that is, from equivalent starting points, some people will just be luckier and earn more than others—as a type of the idiosyncratic risk that Fernholz and Fernholz focus on.

I think this is a useful antidote to the widespread belief that outcomes are solely due to skill, hard work, or some other “virtuous” attribute. Even if everyone starts off equal, you’re going to have a few big, big winners and a lot of losers. Because we want to find order and meaning in the universe, we like to think that success is deserved, but it almost always comes with a healthy serving of luck. Bear that in mind the next time you hear some gazillionaire hedge fund manager or corporate CEO insisting that he knows how the country ought to be run.

October 8, 2012

The Problems with Software Patents

By James Kwak

Charles Duhigg and Steve Lohr have a long article in the Times about the problems with the software patent “system.” There isn’t much that’s new, which isn’t really a fault of the article. Everyone in the industry knows about the problems—companies getting ridiculously broad patents and then using them to extort settlements or put small companies out of business—so all you have to do is talk to any random group of software engineers. And it’s not as much fun as the This American Life story on software patents, “When Patents Attack!” But it’s still good that they highlight the issues for a larger audience.

The article does have a nice example of examiner shopping: Apple filed essentially the same patent ten times until it was approved on the tenth try. So now Apple has a patent on a universal search box that searches across multiple sources. That’s something that Google and other companies have been doing for years, although perhaps not before 2004, when Apple first applied. There’s another kind of examiner shopping, where you file multiple, similar patents on the same day and hope that they go to different examiners, one of whom is likely to grant the patent.

According to law professor Jay Kesan, things are fine as they are: “If someone gets a bad patent, so what? You can request a re-examination. You can go to court to invalidate the patent.” But Kesan must know the costs of patent litigation—potentially tens of millions of dollars for a trial that goes on for years, which can easily swamp a startup’s budget. And in the meantime, corporate customers will be uneasy about buying a product that could be enjoined because of twelve random people in Delaware. Duhigg and Lohr profile Vlingo, a voice-recognition company that won against a patent infringement suit brought by Nuance, its larger competitor—but sold out to Nuance rather than have to pay for four more similar suits.

Vlingo’s founder since decided to quit the voice recognition field—his area of scientific expertise—because of the legal landscape. I would have serious second thoughts about starting another software company today, given what I know about software patents. How is that good?

The bad news, if you need any more, is that we only have one patent system. And much as software people hate it, pharmaceutical people like it—or, rather, they want to make it even easier to get and use patents. Since pharma outweighs software in Washington, change is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers