Simon Johnson's Blog, page 34

September 14, 2012

Simple or Complex?

By James Kwak

Ever since the financial crisis, there has been an on-again, off-again debate over the right model for financial regulation. On the one hand are those who favor simpler rules—such as a simple leverage limit based on total unweighted assets—on the grounds that they are easier to monitor and tougher to game. On the other hand are those who favor complex rules—such as the Dodd-Frank Act, which has so far generated over 8,000 pages of rules—on the grounds that the world is complicated so we need complicated rules. For the most part, this has been a shouting match over broad principles.

A friend sent me Andrew Haldane’s paper from Jackson Hole a couple of weeks ago, “The Dog and the Frisbee.” (The title refers to the ability of a dog—or a child—to catch a frisbee by following a single visual heuristic, ignoring factors such as the rotational speed of the frisbee or wind currents.) Now we have evidence.

Financial regulations have become fabulously complex in recent decades. For example, Haldane points out that since Basel II allowed banks to use internal risk management models for calculating their risk-weighted assets and capital, capital regulation is now performed by models that potentially include millions of parameters that must be estimated (p. 9). But these parameters must be estimated using relatively short historical samples—drawn from a historical period that may or may not be representative of the future.

Here we collide with another fact of statistics: when you have a limited amount of sample data, simple models have greater predictive accuracy than complex models. Haldane cites examples from a number of fields. For example, to predict the winner of a tennis or soccer match, you are better off going by the name recognition of the player or team rather than by the quantitative rankings put out by ATP or FIFA (p. 5). And when determining your asset allocation, you are better off dividing your assets evenly among all asset classes than by doing mean-variance optimization using historical data (p. 6).*

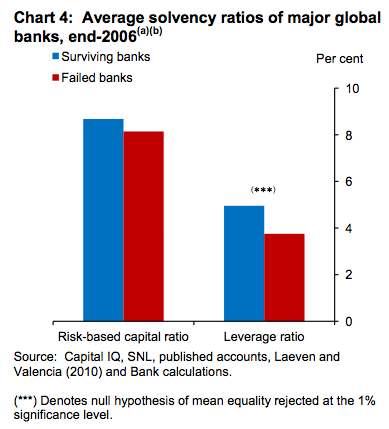

So what happens with financial regulation? Haldane analyzes various data on banks from before the financial crisis and on which banks failed (or would have failed absent government intervention) during the crisis. The conclusions? Looking at banks with over $100 billion in assets at the end of 2006, risk-based capital ratios fail to predict which would fail when the crisis hit; simple leverage ratios without weighting assets were statistically significant at the 1% level. (See Tables 3–5 for more specifications.)

The same does not hold for smaller banks, as shown by a sample of FDIC-insured banks. But that’s because of the large sample size. Haldane simulates what would happen if you estimated your models using a partial sample and then tried to predict what would happen to the rest of the sample. In that case, again, simple metrics perform better than complex models.

So what can we conclude from this? One possibility is that banks are just good at gaming the system, and the more complicated the system, the more opportunities for gaming there are. So should we vastly increase the number of regulators to keep pace with the banks and their law firms? That’s unlikely to happen in today’s environment of (self-imposed) budget constraints. More importantly, however, the real problem isn’t that risk management models can be gamed; it’s that they don’t work when the complexity of the model dwarfs the available data from which the model is estimated.

One possibility is increasing supervisory discretion. The risk there is that it would only increase the risk of (and returns to) regulatory capture. At the end, Haldane comes back to the root of the problem. The problem is complexity, and so we need to reduce complexity. One way is to tax it. Another is to insist on structural reforms to complex financial institutions. Until then, all the models in the world will do little more than give regulators the false impression that they are in control.

* Of course, if you’re predicting past performance using past data, there are superior strategies. But that’s not the point of investing, or of financial regulation.

September 13, 2012

Introducing The Latin Euro

By Peter Boone and Simon Johnson

The verdict is now in: traditional German values lost and the Latin perspective won. Germany fought hard over many years to include “no bailout” clauses in the Maastricht Treaty (the founding document of the euro currency area), and to limit the rights of the European Central Bank (ECB) to lend directly to national governments. Last week, the ECB governing council – over German objections – authorized purchasing unlimited quantities of short-term national debts and effectively erased any traditional Germanic restrictions on its operations. (The finding this week by the German Constitutional Court — that intra-European financial rescue funds are consistent with German law — is just icing on this cake, as far as those who support bailouts are concerned.)

With this critical defeat at the ECB, Germany is forced to concede two points. First, without the possibility of large-scale central bank purchases of government debt for countries such as Spain and Italy, the euro area was set to collapse. And second, that “one nation, one vote” really does rule at the ECB; Germany has around ¼ of the population of the euro area (81 million out of a total around 333 million), but only one vote out of 17 on the ECB governing council – and apparently no veto. The balance of power and decision-making has shifted towards the troubled periphery of Europe. The “soft money” wing of the euro area is in the ascendancy.

This is not the end of the crisis but rather just the next stage. The fact that the ECB is willing to purchase unlimited debt from highly indebted nations should not make anyone jump for joy. The previous rule forbidding this was in place for good reason – the German government did not want investors to feel they could lend freely to any euro area nation, and then be bailed out by Germany. Now investors know they can be bailed out by Germans, both directly through fiscal transfers and through credit provided by the European Central Bank. How does that affect the incentives of borrowers to be careful?

Spain’s Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy has now launched the next front in the intra-European credit struggle. Despite the announcement of ECB support, Mr. Rajoy remains elusive regarding whether he would seek the money. His main concern is that the ECB is insisting that the International Monetary Fund, along with the European Union commission and perhaps the ECB itself, negotiate an austerity program with any nation that needs funds. Such an austerity program is the “conditionality” which the ECB had to claim will exist in order to justify the large bailouts they are promising.

So the new battleground moves from whether the ECB can bailout nations to whether austerity programs should be required for bailouts. The periphery will fight this issue tooth and nail, and they will win. Unemployment in Spain is now around 25 percent and in Greece it is at 24.4% (with unemployment for young people aged 14 to 24 now at 55 percent). Both Portugal and Ireland have made progress implementing their austerity programs, but they are not growing and their debts remain very large (gross general government debt is projected by the IMF’s Fiscal Monitor to be 115 percent of GDP next year in Portugal and 118 percent of GDP in Ireland). The current Italian government is well regarded, but there are large political battles ahead and it is also burdened with big debts (to reach 124 percent of GDP in 2013).

At the same time, European countries that are outside the euro – such as the UK, Sweden, Poland and Norway – are all seen as faring much better.

The Germans will be increasingly drawn towards one plausible conclusion: Perhaps the euro area is simply the wrong system. If tough austerity programs do not wrest nations free from high unemployment and over-indebtedness, then how are they to get back on the path to growth? If a one-time devaluation could help release nations from their troubles rather more quickly, perhaps Germany should instead admit – or insist – that the single currency is a failed exchange rate regime?

The ECB is now fighting for its survival as an organization. ECB President Mario Draghi and his colleagues have stretched the rule book in order to open the money spigots to purchase troubled nations’ debts. The leaders of troubled nations will fight hard to get all they can with as few promises in return as possible. Elected officials must do this, or they will lose elections.

Europe has strong institutions – good property rights and vibrant democracy. An independent central bank was long seen as an important manifestation of such institutions. But powerful interests have shifted towards wanting easy credit above all else. And the more the ECB provides such credit, the more powerful those voices on the periphery will become.

We’ve seen such a dynamic operate time and again around the world. When strong regional governments are fighting for resources against national governments, there is a tendency for regions to accumulate large debts, and then demand new bailouts at the national level. Often these battles end in runaway inflations or messy defaults, or both (think Argentina many times or Russia in the 1990s).

The ECB has handed the euro zone’s peripheral governments a great victory at the expense of those who hoped to keep the euro area solvent and a “hard currency” zone through disciplined public finance.

It may be difficult to imagine that wealthy European nations could follow the tragic path to inflation and defaults seen for so long in Latin America, yet with each “step forward” in this euro crisis, Europe moves further along that same route.

An edited version of this post appeared this morning on the NYT.com’s Economix blog; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

September 11, 2012

No There There

By James Kwak

On the one hand, over in Romney headquarters, they can take heart from the fact that the economy continues to sputter, as evidenced by the latest jobs report. On the other hand, as the election draws near, people will only ask more questions about what President Romney would actually do. For months now, the campaign has whispered one thing to the base (e.g., “severely conservative”) while being purposefully vague to everyone else, hoping that independents will assume he is still the moderate who introduced universal health care to Massachusetts. Now that strategy is breaking down.

Exhibit A is yesterday’s comical back-and-forth-and-forth-and-back on the Affordable Care Act. But the more important Exhibit B is the Romney “tax plan”—you know, the one that cuts rates for everyone by 20 percent, yet does not reduce revenues, does not increase taxes on the middle class, and achieves this miracle by eliminating tax expenditures, but without touching the preferences for investment income or the mortgage interest tax deduction.

Back in February I wrote that this is a mathematical impossibility. The Times recently reported that it is still impossible, citing both Tax Wonk in Chief William Gale of Brookings and an Alan Viard of AEI(!).

Romney’s campaign continues to refuse to fill in the details, which isn’t surprising, since they can’t. But they can’t avoid the subject, either, since they want to make this an election about the economy—and their plan to improve the economy is, to a first approximation, their plan to cut tax rates.

Coupled with Romney’s refusal to release more details of his own taxes, including the magical IRA, the impression one gets is that he doesn’t want to talk about details; he’s just hoping that people dislike President Obama enough and trust him enough to get him through the election. The problem with that is Mitt Romney is no Ronald Reagan. He has no charisma, and the basis of his pitch is that he’s a skilled businessman. It’s also doesn’t make sense to play a prevent defense when you’re behind. But there’s no getting around the laws of arithmetic.

September 10, 2012

The Problem with Bankers’ Pay

By James Kwak

From today’s WSJ:

“At J.P. Morgan, the biggest U.S. bank by assets, directors are considering lower 2012 bonuses for Chief Executive James Dimon and other top executives in the wake of a multibillion-dollar trading disaster, said people close to the discussions. But they also are grappling with the question of how to do that without drastically reducing the executives’ take-home pay.”

Huh? Isn’t reducing their take-home pay the point?

Who Built That?

By Simon Johnson

Perhaps the biggest issue of this presidential election is the relationship between government and private business. President Obama recently offended some people by appearing to imply that private entrepreneurs did not build their companies without the help of others (although there is some debate about what he was really saying).

Mitt Romney’s choice of Paul D. Ryan as vice presidential running mate is widely interpreted as signaling the further rise of the Tea Party movement within the Republican Party – with the implication that the private sector may soon be pushing back even more against the role of government.

For most of the last 200 years, national economic prosperity has been about creating and sustaining a symbiotic relationship between government and private business, including entrepreneurs who build businesses from scratch. This symbiosis was long a great strength of the United States, something it got right while other nations failed to do so, in various ways.

Is the partnership between government and business now really on the rocks? What would be the implications for longer-run economic growth of any such traumatic divorce?

To think about these issues, I suggest starting with “Why Nations Fail” by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, a sweeping treatise on political power and economic history. (I have worked with the authors on related issues, but I wasn’t involved in writing the book. I am using their material as a reference point throughout my new course this fall at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, “Global Controversies.”)

Income per capita in 1750 was relatively similar around the world. There were some pockets of prosperity – imperial capitals and trading cities – but most people lived at roughly the same level of income (and lived about the same length of time). That changed dramatically in the hundred years after 1800; some countries charged ahead in terms of industrialization and broader economic development, while others lagged. (Lant Pritchett memorably labeled this phenomenon “Divergence, Big Time.”) Since 1900, while average income levels have risen almost everywhere, there has been surprisingly little convergence in income per capita. Countries that were relatively rich in 1900 are, for the most part, relatively rich today. Most countries that were poor in 1900 have failed to catch up with the highest income levels today – with some notable exceptions in East Asia and for some countries with a great deal of oil.

In the Acemoglu-Robinson view, it was all about having a favorable head start – based on strong and fair rules of the game:

“Countries such as Great Britain and the United States became rich because their citizens overthrew the elites who controlled power and created a society where political rights were much more broadly distributed, where the government was accountable and responsive to citizens, and where the great mass of people could take advantage of economic opportunities.”

These were excellent conditions for innovation and private-sector investment. People who were not born wealthy were able to educate themselves and create their own enterprises. But the government also played a very helpful role, with investments in clean water and public health, developing public education and supporting the creation of transportation and communication networks.

Equality before the law also became an essential component of successful societies – for example, much more present in the United States than in Mexico.

At least in the 19th century, government cooperated closely with private business in the United States. In much of the world, this relationship has never worked well – and conditions for growth are consequently undermined. “Why Nations Fail” explores in great detail exactly when and why politicians choke business, how economic oligarchs capture and abuse political power and what happens when militaries become too powerful. It is sobering reading.

“Why Nations Fail” has been very successful, in part because the history appeals to people on both the right and the left of the political spectrum. To those on the right, economic development requires strong property rights. To those on the left, constraints on the power of elites are essential. Both views garner a great deal of support from the Acemoglu-Robinson view of how the United States, Western Europe and a few other places did so well.

The United States avoided the problems on which the book focuses, but nevertheless it now faces a major struggle regarding the nature of its society — and its future.

The 20th century brought a new and expanded role for government, putting into effect regulations that constrained what private business could do (starting with antitrust laws and food purity rules), providing various forms of social insurance (including old-age pensions) and increasing marginal tax rates (particularly on income). The modern federal government also operates a global military presence on a scale unimaginable to any American before 1941.

Unlike the populations of some countries, the American people have never reached a consensus over what was achieved and what was given up in the 1930s. In the United States, the rising role of the state produced a long-term backlash, culminating most recently in the form of a tax revolt (from the 1960s), a move to the right in the Republican Party (beginning with Ronald Reagan and running through Newt Gingrich directly to Mr. Ryan) and a deep-seated conviction that tax rates and government spending must be reduced (“starve the beast”).

The discussion of Mr. Ryan and his budget ideas is likely to become central to the election over the next two months – and this is entirely appropriate.

A powerful coalition has risen against the state. It sees modern government as abusive and as standing in the way of economic recovery and growth. There is a strong urge to undo the reforms of the 1930s and roll back government at all levels. The economist Arthur Laffer spoke for many others when he said, “Government spending doesn’t create jobs, it destroys jobs.”

In truth, we all built the modern American economy. This certainly includes individuals taking responsibility for themselves, becoming more educated and working hard to develop their own companies. But the government also played a constructive role.

Can our political system reach a reasonable agreement on how to divide the benefits and share the costs? In “White House Burning,” James Kwak and I proposed one way to do this – phasing in a fiscal adjustment based on the principle that revenue should return to where it was before the Bush tax cuts. Mr. Ryan is proposing a very different vision: phasing out the nonmilitary part of federal government.

In my assessment last month, I found that anything close to Mr. Ryan’s version would be too extreme.

Mr. Ryan wants to strengthen the private sector and get government out of the way. In my reading of Professors Acemoglu and Robinson, Mr. Ryan’s fiscal intentions would destroy the positive role of government in modern America — throwing the baby out with the bath water. This would not be good for continued private-sector development, on which we all depend.

This blog post appeared last week on the NYT.com’s Economix site; it is used here with permission. If you would like to reproduce the entire column, please contact the New York Times.

September 7, 2012

Dominos

By James Kwak

So, as everyone knows, the ECB came out yesterday with its latest plan to stem the creeping European sovereign debt crisis. This one involves potentially unlimited ECB purchases of sovereign debt, so long as its maturity is less than three years (presumably so that the ECB can pull the plug within three years on non-complying governments) and the country in question agrees to comply with fiscal policy reforms (i.e., austerity).

I don’t have any particular ability to forecast whether this will succeed or fail. My inclination is that it will succeed for a while and then turn out to be insufficient, for the reasons that others have identified. Central bank bond-buying will enable governments to borrow money at manageable yields, so their national debt will not spiral out of control solely because of climbing interest rates. But to bring debt levels down will require actual economic growth, and more austerity—even if it isn’t quite as austere as that imposed on Greece in the past—will not generate growth. In addition, the ECB’s promise to “sterilize” its bond purchases—I believe by selling other assets to raise the cash for bond purchases, so the net effect will not be to create money—means that this is not a particularly expansionary form of monetary policy.

This is as good an occasion as any, however, to ask a question I’ve been wondering about for, oh, years now. Every discussion of the European crisis includes the following domino theory (although no one calls it that anymore, for reasons I’ll get back to): If Greece leaves the Eurozone, that proves that it is possible to leave the Eurozone—or, put another way, that the powers that be cannot keep the Eurozone intact. If people realize that it is possible, then bond markets will bet even more heavily against Spain and Italy, which will force them to leave the Eurozone, which would be terrible. Hence Greece cannot leave the Eurozone.

The reason no one calls this a domino theory anymore is that the original domino theory was thoroughly discredited. Remember the fall of Vietnam? Do you remember the ensuing communist takeover of the free world? No, because it didn’t happen.

It seems to me that the current version of the domino theory, where Greece plays the role of Vietnam, rests on a logical flaw. The premise is that (a) if Greece leaves the Eurozone, that implies that the powers that be (Germany, the ECB, the IMF, etc.) are incapable of preventing any individual country from leaving the Eurozone. This ignores two other obvious logical possibilities. One is that (b) the powers that be might have the ability to protect any country they choose to protect, but might decide that Greece is not worth the trouble. The other is that (c) the powers that be might have the ability to protect some countries that are not in such bad shape as Greece (Spain and Italy come to mind).

For whatever reason, the powers that be have chosen to embrace the domino theory, calling the euro “irrreversible,” among other things. In practice, this means that they have staked their credibility on keeping Greece in the Eurozone. And having committed themselves to this position, they have ensured that should Greece leave the Eurozone, it will be interpreted to mean (a) rather than (b) or (c). In other words, by embracing the domino theory, they have made the domino theory more likely to actually be true. Which means that despite yesterday’s announcement, the future of the euro still depends on the ability of Greece’s incompetent, unloved political class to continue imposing austerity on its people.

August 25, 2012

One Man Against The Wall Street Lobby

By Simon Johnson

Two diametrically opposed views of Wall Street and the dangers posed by global megabanks came more clearly into focus last week. On the one hand, William B. Harrison, Jr. – former chairman of JP Morgan Chase – argued in the New York Times that today’s massive banks are an essential part of a well-functioning market economy, and not at all helped by implicit government subsidies.

On the other hand, there is a new powerful voice who knows how big banks really work and who is willing to tell the truth in great and convincing detail. Jeff Connaughton – a former senior political adviser who has worked both for and against powerful Wall Street interests over the years – has just published a page-turning memoir that is also a damning critique of how Wall Street operates, the political capture of Washington, and our collective failure to reform finance in the past four years. “The Payoff: Why Wall Street Always Wins,” is the perfect antidote to disinformation put about by global megabanks and their friends.

Specifically, Mr. Harrison makes six related arguments regarding why we should not break up our largest banks. Each of these is clearly and directly refuted by Mr. Connaughton’s experience and the evidence he presents.

First, Mr. Harrison claims that megabanks are the natural outgrowth of requests from customers, rather than the result of extraordinary resources spent on lobbying over the past 30 years. Mr. Connaughton’s book contains all you need to know – and more than you can stomach – about the realities of how the influence industry has worked diligently to build and defend megabanks. The people who really wanted the banks to become bigger were the executives in charge of those organizations – like Mr. Harrison. They spent a lot of money to make this happen.

Second, Mr. Harrison takes the view that global megabanks at their current scale provide some special services that cannot be otherwise provided by smaller financial institutions.

As Mr. Connaughton points out – including in a new blog post – there are no economies of scale or scope in banks with over $100 billion of total assets. Our largest banks, properly measured, now have balance sheets between $2 trillion and $4 trillion. Plenty of people have attempted to show megabanks produce some magic for broader economy-wide productivity or multinational nonfinancial firms, but there is simply no evidence. Again, read Mr. Connaughton’s book for more detail – or look at my book with James Kwak on this topic, “13 Bankers”.

Third, Mr. Harrison claims “large global institutions have often proved more resilient than others because their diversified business model ensures that losses in one part of the enterprise can be cushioned by revenues in other parts.”

Mr. Connaughton’s book reminds us, with some eloquence, that Citigroup and Bank of America – the largest U.S. financial institutions in 2008 – would have failed if it were not for the government bailouts that they received. As a matter of simple historical fact, the “more resilient” in Mr. Harrison’s version of history is exactly the same as observing that those banks were seen by officials as “too big to fail.” Their resilience came solely from support provided by the government and the Federal Reserve.

Fourth, Mr. Harrison denies that very large banks receive any implicit government subsidies. To support this view, Mr. Harrison suggests we should compare borrowing costs across financial and nonfinancial firms that share a similar bond rating (e.g., AA); he points out that the interest rate paid by financial firms in this comparison is higher. But the interest rate at which a company borrows depends not just on the risk of default, but also on the “recovery value” in the case of default (i.e., how much do creditors end up with after the company has been wound down). If you think you will recover less when I default, you should charge me a higher risk premium – and thus a higher interest rate.

Mr. Harrison compares apples (finance) with oranges (nonfinance) – and fails to mention that the recovery rate in the latter case is much higher. How much will investors recover in the case of Lehman, for example – perhaps 25 cents after more than four years? For most nonfinancial companies, default does not by itself result in a big reduction in value (the deadweight costs for bankruptcy of such firms in the US are quite small); large financial firms are quite different (the deadweight bankruptcy costs are typically huge). Mr. Harrison’s proposed comparison is simply uninformative – you need to look at comparisons within the financial sector.

The right comparison is the funding cost of financial firms with and without implicit government support. The funding advantage for those perceived as Too Big To Fail is estimated to be between 25 and 75 basis points; most people close to the issue think it is at least 50 basis points. The idea that megabanks do not get huge, implicit subsides is simply priceless – again, read Mr. Connaughton’s account to see the lengths to which the banks will go to ensure these subsidies are kept in place.

Fifth, Mr. Harrison says that “complexity can be an antidote to risk, rather than a cause of it”. On the contrary, the evidence suggests that management has consistently lost control over financial institutions with hundreds of thousands of employees in 50-100 countries. Think about the scandals of this summer: Barclays and Libor; HSBC or Standard Chartered and money laundering; and the severe breakdown of risk management at JP Morgan Chase. In each case, executives claim they did not know what was going on. The very largest banks have become too big to manage.

Sixth, Mr. Harrison claims regulators are not cowed by banks. “The Payoff” is all about how lobbying really works – and how legislators and regulators are brought to heel. Money brings influence and influence is used to make more money. It is not about “cowing” anyone; it is about persuading them that you are right and should be allowed to do exactly what you want to do, even though your arguments are completely specious. Mr. Harrison’s op ed is a nice example of the genre.

Some regulators have started to stand up to big banks on some issues, and this should be encouraged. But overall, Wall Street prevails on all the major issues, and most top officials at Treasury and the Federal Reserve are only too happy to cooperate.

Mr. Harrison makes strong claims. All of his arguments are demonstrably false. If you think Mr. Harrison and the other defenders of megabanks have even the slightest veneer of plausibility, you must read Jeff Connaughton’s book.

August 23, 2012

Why Does Wall Street Always Win?

By Simon Johnson

After a long summer of high-profile scandals – JPMorgan Chase trading, Barclays rate-fixing, HSBC money-laundering and more – the debate about the financial sector is becoming livelier.

Why has it has become so excessively dominated by relatively few very large companies? What damage can it do to the rest of us? What reasonable policy changes could bring global megabanks more nearly under control? And why is this unlikely to happen?

If any of these questions interest you – or keep you awake at night – you should take another look at the last time we had this debate at the national level, and reflect on the work of Ted Kaufman, the former Democratic senator from Delaware, who was far ahead of almost everyone in recognizing the problem and thinking about what to do.

Senator Kaufman represented Delaware in 2009 and 2010, and Jeff Connaughton – his chief of staff – has a new book that puts you in the room. In “The Payoff: Why Wall Street Always Wins,” we see Senator Kaufman as chairman of oversight hearings on the Justice Department and the F.B.I.’s pursuit of financial fraud, pushing the Securities and Exchange Commission on the dangerous rise of computerized trading and working with Senator Sherrod Brown, Democratic of Ohio, on the legislative fight to impose a hard cap on the size and debts of our largest banks. (I wrote many pieces supporting the work of Senator Kaufman at the time, including in this space, but I never worked for him.)

Mr. Kaufman was unique in ways that should give us pause. He was appointed to his seat (after Joe Biden became vice president) and immediately said he wouldn’t run in the next election. So he never had to raise any money to reach the Senate or stay there longer. His experience gives us a glimpse of what we would get if we could really remove the money from politics.

Mr. Connaughton is a fascinating witness and raconteur because he’s been through the revolving door several times: in between work in the Senate and the Clinton White House, he spent 12 years in one of Washington’s top lobbying firms. This author has really lived in and understood the Wall Street-Washington corridor. The book is partly about his education – and ultimate disappointment, most of all with the Obama administration but definitely with both parties.

The system is rotten, to be sure, but this president came to office promising change – and that is exactly what we did not get on most crucial dimensions related to the financial sector. The failure depicted on this front is political and ultimately about money – and all the power that Wall Street can buy, one way or another.

The book is also about the details – the legislative and bureaucratic regulatory process through which your future prosperity is sold down the river. If you don’t follow the details, you’ll never really understand what happened to this country. Mr. Connaughton has done us a great service in laying all bare.

But be warned; while fascinating, much of what is in this book will turn your stomach. Mr. Connaughton is now out of politics, and I very much doubt that he will ever return. Hence the complete honesty missing in most political memoirs; no bridge is left unburned.

The Justice Department declines to prosecute financial fraud, the S.E.C. fails to protect average investors, and the Senate refuses to stand up to the Treasury and Federal Reserve technocrats aiming to keep too-big-to-fail in place.

Wall Street is manifestly too powerful and showers too much money on former and future public servants in Washington. Our political system could not respond meaningfully even to a devastating financial crisis that brought the country to its knees. While this book is about the past, the implications for the future are clear.

The apathy on the part of public officials during this administration is pervasive and frequently appalling. As Mr. Connaughton puts it,

“For me, what is deplorable is not the Justice Department’s failure to bring charges, but its failure to be adequately dedicated and organized either to make the cases or reach a fully informed judgment that no case could be made.”

The administration apparently thought that any kind of legal action against major players in the financial sector would slow the recovery; this point of view seems to have come from the very top, in the White House and at the Treasury. As a result, then and now, Mr. Connaughton writes, “Too-big-to-fail banks continue to act lawlessly, teeter on the brink and destabilize the global economy.”

On the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislative debate in early 2010, “the Treasury Department was taking a tougher line in negotiations than the Republican senators whose votes were in play,” the author tells us, meaning that Treasury was more on the side of big banks.

And, in case you previously did not get the memo about how all this really works,

“The Blob (it’s really called that) refers to the government entities that regulate the finance industry – like the banking committee, Treasury Department and S.E.C. – and the army of Wall Street representatives and lobbyists that continuously surrounds and permeates them. The Blob moves together. Its members are in constant contact by e-mail and phone. They dine, drink and take vacations together. Not surprisingly, they frequently intermarry.”

Could we change all of this in the world’s greatest democracy? Mr. Connaughton exhorts us: “Every voter who wants to break Wall Street’s hold on Washington should put congressional and presidential candidates to the test,” demanding that they shun lobbyists’ contributions and asking, “Will you agree not to take campaign contributions from too-big-to-fail banks and non-banks?”

Will it happen? This seems unlikely within our existing party system. It would take a broader citizens’ movement, a groundswell of educated opinion focused on breaking the political power of Wall Street and ending the enormous, nontransparent and dangerous subsidies currently received by very large financial institutions.

Intellectually, the right and the left can unite on this issue. But where are the political leadership and organization needed? We had a huge crisis and elected a president who promised change – and that didn’t make much difference. The biggest Wall Street firms are larger and probably now more powerful than they were in the run-up to 2008.

Read Mr. Connaughton’s account and think about what real change would involve.

An edited version of this post previously appeared on the NYT.com’s Economix blog; it is used here with permission.

August 22, 2012

The Future According to Facebook

By James Kwak

From the Times:

“Doug Purdy, the director of developer products, painted Facebook’s future with great enthusiasm . . . One day soon, he said, the Facebook newsfeed on your mobile phone would deliver to you everything you want to know: what news to digest, what movies to watch, where to eat and honeymoon, what kind of crib to buy for your first born. It would all be based on what you and your Facebook friends liked.”

Does that sound to you like a good thing? Even assuming for the sake of argument that Facebook does not let commercial considerations interfere with that “newsfeed” (and we know it already has, with Sponsored Stories), or otherwise tweak its algorithms to influence what you see:

First, do you really want your view of the world shaped by your friends? I mean, I like my friends, but I don’t count on them to, for example, tell me which NBER working papers are worth reading, let alone what crib to buy. (In Facebook’s theory, my friends are the people with similar tastes to mine, but that’s not how it works in the real world. For example, I liked Laguna Beach, and most of my friends thought were horrified to find out. In reality, you have plenty of friends with different tastes from yours, and that’s a good thing. This is why Netflix ratings work better than Facebook friends.)

Second, doesn’t that seem like a terrifying vision of the future? It’s kind of like 1984, except kindler and gentler, because Big Brother has been replaced by the most effective form of peer pressure ever invented. At the same time, humanity has splintered into millions of tiny (though overlapping) tribes, each with its own version of the Internet and hence its own set of facts.

Mitt Romney And Extreme Fiscal Policy

By Simon Johnson

As the presumptive Republican vice presidential candidate, Representative Paul D. Ryan of Wisconsin and his plans for the federal budget are drawing increasing interest. Mr. Ryan has been chairman of the House Budget Committee since the Republicans took control of the House of Representatives in the 2010 midterm elections and has articulated a vision for federal public finances that is quite different from what other prominent Republicans have been advocating – including Mitt Romney.

The contrast between Mr. Romney and Mr. Ryan tells us a great deal about the competition among fiscal ideas within the Republican Party. It also highlights the challenge Mr. Romney will face in November, if he is shifting rightward toward Mr. Ryan’s approach to budget policy, away from independents in the center of the political spectrum.

The budget ideas of Mr. Romney and the other Republican presidential candidates in the primaries mostly focused on proposals to cut taxes. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget assessed Mr. Romney’s specific ideas as likely to increase national debt to close to 100 percent of gross domestic product by 2021, using net federal debt held by the private sector, which is currently around 75 percent of G.D.P. (I use the high debt scenario when thinking about any political candidates’ proposals; in my experience, something almost always goes wrong with more rosy forecasts.) Mr. Romney has mentioned cutting tax expenditures – i.e., ways in which the government spends through giving various kinds of tax breaks – but so far he has been very vague on the details. To date, Mr. Romney has stood for cutting taxes and therefore increasing the deficit and debt relative to what it would otherwise be. (He embraces the widely optimistic notion that such cuts would stimulate investment and lead to job creation, which in turn would increase tax revenues; previous tax cuts have not accomplished this.)

Mr. Ryan is different. Rather than just wanting to cut taxes, he definitely and very specifically wants to reduce government spending. Mr. Ryan’s proposals are phased in – and in some versions debt would increase a great deal before it stabilizes. The difference between his approach and Mr. Romney’s is fundamental and clear: Mr. Ryan tells you what he would cut.

His Medicare proposals have received the most attention. Two Ryan variants have been placed on the table. In the first, he would phase out Medicare and replace it with a voucher program. The Congressional Budget Office does not generally score budget resolutions, as these are not detailed enough to be amenable to their calculations; the resolutions are more of a framework than legislation. But this Medicare proposal, part of Mr. Ryan’s 2011 budget, was scored by the C.B.O. at Mr. Ryan’s request. (I’m on the C.B.O.’s Panel of Economic Advisers, though I’m not involved in any of its budget work.)

Mr. Ryan must have been surprised and disappointed when the C.B.O. determined that changing Medicare in this fashion would actually increase total health-care costs (as a percentage of the economy).

The reasoning is straightforward. At present the federal government buys health care for about 100 million Americans. Buying at scale and pooling risks, the government can get lower prices than you would get on your own.

Medicare is also highly efficient in terms of its administrative costs, which are about one-fifth of what it costs to run leading private insurance companies.

Mr. Ryan’s second and more recent proposal involves offering a voucher program but also continuing traditional Medicare – a kind of “public option” that was derided by many on the right during the health-care debate of 2009-10. This plan has not been scored by the Congressional Budget Office – it would be too much of a stretch using the standard budget methodology. But it’s clear that under the voucher plan, the risk of higher health-care costs, now covered by the government, would be transferred to the individuals.

If you believe in the magic of the market under all circumstances, then Mr. Ryan’s plan has appeal. But we have had a great deal of market competition for decades in health care – look at the insurance plans and hospitals around you – and health-care costs have not been brought under control.

It is hard to see how any version of his proposals would reduce health-care costs, although he could certainly cap what the government pays for health care. Would that really lower costs or just shift more risks onto retired people?

The more dramatic part of Mr. Ryan’s budget is for government spending other than on Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP (a health program for children), Social Security and net interest payments (this is close to what is known as discretionary spending). My colleague James Kwak calculates that Mr. Ryan would bring this spending down from its likely medium-term projection of 8 percent of G.D.P. toward 4 percent of G.D.P. (or even lower).

Given Mr. Ryan’s other pronouncements, it is reasonable to assume that he would not want military spending below its post-World War II low point, which was 3 percent of G.D.P. If you factor that into the projections – see the second chart by James Kwak on the previous link – non-defense discretionary spending would fall below 1 percent of G.D.P. (from its average since the 1960s of 6 to 7 percent of G.D.P.).

Mr. Ryan stands for substantially phasing out not just Medicare but also the federal government. This may help boost turnout among the conservative base, but will this extreme vision really help Mr. Romney win over independent voters or disaffected Democrats?

A version of this post previously appeared on the NYT.com’s Economix blog. It is used here with permission.

Simon Johnson's Blog

- Simon Johnson's profile

- 78 followers