P.J. Fox's Blog, page 9

October 23, 2015

Where’s the Meat?

Little old ladies (at least according to Wendy’s commercials) aren’t this gullible; why are authors so gullible? Why do they–we–tend to accept the claims of whomever we’re speaking to at face value? If they say they’re a publisher then great! They are. If they say that, as a publisher, they have certain credentials, experience, etc then great! That must all be true. Because no one ever lied to anyone, in the hopes of taking their money. Right?

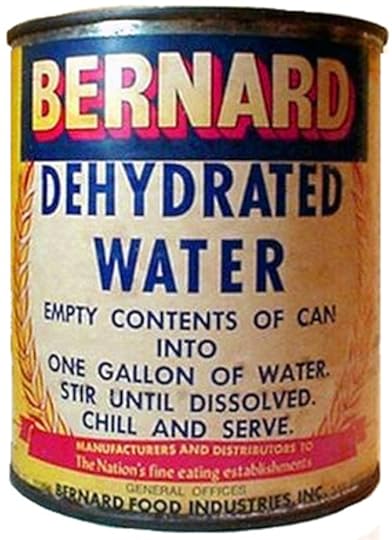

Take two and call me in the morning.

The internet is awash, particularly lately, with the kind of snake oil salesman-style “publisher” I’ve written about before. They can’t do anything for you that you can’t do for yourself, except sell you a delusion. A very expensive delusion. They’re “publishing houses” the way anyone who creates their own imprint is a publishing house: they might have the dubious cachet of a website and maybe even a business card (both pretty easily creatable), but they don’t have the one thing that you, as an author, really need. The only, to my mind, truly valid argument remaining for mainstream publishing. Distribution.

Random House can get your books places. If it wants to. Which it probably doesn’t. As Hugh Howey observed, the choice is between published and not published; not between a pile of paper sitting on your desk and an end-cap at Barnes & Noble. But while it might be foolish to pin all your hopes on Random House, or whomever, making your dreams come true, it’s even more foolish to pin those same hopes on your random neighbor. Who may or may not have ever left his basement. Let alone done any of the things he’s claimed.

When someone tells me, with the aim of parting me from my money, that they’ve attended X field or worked in Y industry, I want to see their CV. Maybe this is a lifetime of reading fairy tales speaking, but I actually question new lamps for old and similar schemes. What’s in it for the other guy? If he’s really so successful, then why is he soliciting me?

It’d be nice to think of myself as just that awesome. That’s what a certain segment of the population wants me to think. To be sure. But, although my self esteem could certainly use some boosting, I stick to taking my compliments from people who aren’t trying to sell me something. And if a “publishing house” is posting to your page, or in your writing group then yes, they are.

These outfits aren’t agents of altruism. They didn’t wake up this morning dreaming of your success; they woke up dreaming of their own. Just like, yes, traditional publishers. But like I said, at least with the Big Five there’s some claim that can be made that they’re offering you something. Whereas all the average “publisher” you’ll meet online can offer is exactly what you can offer yourself: print on demand, and limited distribution through Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Would “publishing” scams be so popular–or possible at all–if authors didn’t, as a group, engage in such magical thinking with regards to what publishing actually means? For their wallets and for their legitimacy, as authors? This insistence on traditional publishing’s gatekeepers as being, rather more, the gatekeepers to some kind of Willie Wonka-esque golden ticket creates a lot of problems. Not the least of which is the kind of desperation that leaves people wide open to fraud.

The fact is that while the authors involved might delude themselves that, say, Ragnarok Publications is just as legitimate as any imprint of Random House, readers are a bit more savvy. They know that anyone, publishing a book by any means, can choose any imprint to go with it. And, yes, they’re familiar with their imprints. They know you’re indie; they’re not mistaking your guy for the people at Tor. And of course, no one likes hearing this: because it seems hurtful. And mean-spirited. And upsetting. Because most authors think with their hearts, not their heads.

“I want” is not a business plan. We all want. But before we sign on any dotted line, for anything, we need to take responsibility for our own success by asking some questions. Like, for example, what am I actually getting in exchange. We need to overcome the scarcity mentality that seems to grip so many in this industry and actually ask other authors for help. To seek mentoring from others who’ve gone where we wish to go and, in turn, have the courage to heed their wisdom. And warnings. To move forward with a clear understanding of what the heck it is we’re trying to accomplish–and how, and why.

In the meantime, when it comes to evaluating a potential “publisher,” I’ve developed a one question test. This is for those of you who don’t want to read my lengthier articles (and chapters, in books) on the subject. Or, conversely, for those of you who find yourselves prone to fits of emotion–like me–and need something quick and dirty to pull you back from the edge.

Do they distribute in lots?

That’s the question. As in, do they pay for offset printing. Are books produced, and then shipped, in lots. To warehouses. To stores. Are there, thus, remaindering issues. If not, then you’re dealing with–under whatever guise and through however many layers–a print on demand service. Just like every other indie writer uses. And, while you might want to, you do not need to pay extra for vanity. Because vanity, at that point, is all it is.

October 21, 2015

The Prince’s Slave: What It’s Really About

What follows is the afterword from the last volume of my series (and omnibus edition novel), The Prince’s Slave. For those who haven’t read the series yet, be warned: there are spoilers! As I do discuss the series as a whole, framed in terms of its ending. However, as there has been so much discussion of this series, and what it is and isn’t, elsewhere on the web–is this glorifying sex trafficking, is it romanticizing Stockholm Syndrome–I thought it might be interesting, at least for some, to hear from the author herself.

AFTERWORD

When I told my husband I had writer’s block, about halfway through writing the rough draft of this manuscript, he asked me, “what? Did you run out of orifices?”

Writer’s block—a phenomenon in which I don’t even believe, by the way—is a whole different problem when you’re writing romance. Particularly erotic romance. The challenge is to balance sex and plot in such a way that neither is distracting. Too much plot and it’s not erotic, too much sex and it’s boring. The right balance is what, more than anything else, moves the plot forward.

Not to mention, makes you care what happens to the characters!

Which is its own separate challenge: how do you create characters that, while keeping the fairytale element so crucial to all successful romances, feel real? That both belong in the realm of pretend and yet also transcend it? No one wants to fantasize about the same poorly dressed, slightly smelly man who flirts with us every morning at Starbucks. But, at the same time, the ideal hero is someone who could walk into Starbucks.

There’s a lot of judgment in the world, unfortunately, about what women “should” find attractive, mostly couched in vaguely sociological-sounding theories explaining why they’re somehow misguided. And, all too often, the men in these kinds of stories are presented as abusers—or easily seen that way. Or, even when the character truly doesn’t fit the mold, he’s still squeezed into it in the interests of serving some argument about how porn is wrong or erotica is wrong.

Or, indeed, that women exploring their own sexuality is wrong.

Personally, I don’t think a woman’s sexuality is so frail that her commitment to herself should be judged according to whether others approve of her desires. Liking, for example, bondage doesn’t make a woman “battered,” or even “confused.” It makes her a woman who likes bondage. Women who spend their days as housewives like bondage, and so do women who spend their days in boardrooms.

What a woman likes, in terms of sex, says nothing about her view on feminism and everything about what gets her off.

A truth which lies, I think, at the heart of what makes Beauty and the Beast so enduringly popular.

Belle is named for the Disney character, with whom she shares many commonalities, but the story itself is in fact far older. Originally a medieval tale, it was first put down in writing by a female author, the well-regarded novelist Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, and published in 1756. The same year when the Treaty of Westminster was signed, the first candy factory in the world opened in Germany, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s father published his now-famous textbook on learning to play the violin.

Ironically, most modern versions of Beauty and the Beast focus on something that the original story did not: this notion of a superficially ugly guy being not so bad after all. And what makes him ugly is always superficial. Oh, he has a scar. Or oh, he’s not a billionaire with a gigantic, pulsing…wallet. Which…okay, just how shallow are we saying women are, here?

Moreover, what actually makes a person ugly: what’s on the outside, or what’s on the inside? As far as literary devices go, the disposable “problem,” i.e. the hypothetical scar, is a pretty cheap trick. Easily gotten over, by the heroine and everything else. Because, after all, who really cares? Beauty fades, but bitch is forever. A point that Charlotte makes well, in her last visit to Ash’s castle.

The question of what actually makes someone ugly is usually sidestepped, because the things that make us ugly are almost always a little more challenging to get past. When I was first conceiving of this story I wondered, what would make someone a beast today? What’s the modern equivalent of the wolf outside the door, that so terrified people in the middle ages? Or indeed, the man who’d be regarded as a “beast” during the reign of King George II?

In a time when disfiguring injuries were common, would physical deformity really be seen as terrible? Richard III had severe scoliosis. The whole Hapsburg line was famous for its deformities. Lesser problems like smallpox scars were also common and, indeed, not seen as terribly problematic. Lost teeth, even lost limbs were a fact of life. What were a few scars?

It’s worth noting that the original curse, laid by the mysterious visitor to the prince’s castle, was that his outside match his inside.

In other words, he was already ugly.

As our Belle observes, Beauty and the Beast was written, originally, partly as a bit of propaganda for arranged marriages. It was absolutely as relevant to women of the time, in terms of the issues it addressed, as any number of modern novels are to women today. The ultimate point of the story is that sometimes, what at first appears to be—or in fact is—the husband from Hell can actually turn out to be the perfect match.

Or become one, with a little squinting.

This isn’t an issue of “love him better,” though. Which is what modern audiences tend to miss. Beauty and the Beast was, within the framework of its time, a tale of hope: for the thousands, the hundreds of thousands of women who had no control over their destinies. Who were forced to marry whoever was expedient. The hope, you see, lay in the notion that happily ever after—their own happily ever after, not someone else’s—might still be salvaged from this situation. That a man might be revealed to be better than he first appeared or, indeed, might of his own volition change. Because the Beast, in the end, does change of his own volition. Inspired by his love for a woman.

The principle problem with most modern retellings is they keep the bones of the story but lose the part where it’s a modern story, meant to be relatable to modern women. Jokes about “Stockholm Syndrome relationships” arise from the fact that, to modern women, the story in its most-used form makes no sense. They don’t relate to Belle; she isn’t a modern woman, in any sense, and even if she’s suddenly plunked down in modern day, in some sort of vague lip service to the idea the whole “tale as old as time” bit, her problems are still nonsensical. Modern women don’t, you know, get traded by their fathers over roses.

Of course, they didn’t in the middle ages—or in the 1750’s—either. The rose is a metaphor. For any number of reasons that women were sold into what essentially amounted to indentured servitude. The rose represents something that’s perceived as perfect. To the point of lunacy, even, desired far beyond its actual worth. It doesn’t matter what the object of lust is, really; whether a rose or a chest of jewels. A thing’s value, ultimately, lies in the perception of its value.

Just as in Beauty and the Beast, the rose has greater value than Belle.

As women, today, are still undervalued in comparison with material goods—or, indeed, bought and traded like them.

The rose might be described as the One Ring of its time: the ultimate representation of commercialism, and of its overwhelming pull on even the most seemingly strong-minded. The lust for success is a different kind of lust, to be sure, but an equally powerful one. It’s Belle’s father’s lust that, in the original tale, lands her the clutches of the Beast.

Might she not have found a man who exhibited so much strength of persuasion attractive?

A man—or Beast—who, indeed, exhibited none of her father’s weaknesses?

It’s unfortunate that Belle’s tale is usually told in the context of roses and—seemingly—nonsensical bargains, when her plight continues to be so relevant today. Look anywhere on the globe, and you’ll see no shortage of injustice against women. Why do we rely on flimsy tropes when we can retell this tale in real, immediate terms?

Terms to which everyone can, on some level, relate?

Little imagination is required to envision the ways in which women continue to be used, in service to commercialism: forced marriage and forced companionship, in the form of concubinage, still exists in many countries. As does child marriage. The sex trade exists in every country and many of those who participate do so against their will.

They’re outright forced, or sometimes lured or coerced, into situations from which there is often no escape. As Belle almost is, at the start of this story. This modern Belle, like her original predecessor, finds herself the victim of a system that doesn’t value her. That doesn’t value women, at all. In this sense, she’s the same sort of everywoman that de Beaumont first described: a woman, remarkable not because she’s special but because she’s not. To whom other women, even if their lives are slightly different, can relate in their own powerlessness—and in their being compelled to complete what can feel like a futile struggle.

To not, as our Belle might say, let their situation get them down.

At heart, Beauty and the Beast isn’t about loving someone better but about forging your own “happily ever after” from an otherwise horrendous situation. About the murky gray area between changing your circumstances in order to be happy, and accepting them in order to be happy. About what it means to be an empowered woman when, as so many women do, for various reasons, you find yourself in a situation where you have no choices.

Hearing that this version of Beauty and the Beast takes place in the context of the sex trade was—no pun intended—a turn-off for some potential readers. I’ve already gotten the complaint that retelling the story in this setting ruins the romanticism of the fable. Which neatly sidesteps the point that in no version of this story was becoming the Beast’s captive romantic for Belle. For any of the Belles, in any of the versions. In order for the Beast’s transformation—or hers—to mean anything, one has to, I think, tap into that fear. That loathing. That sense of crushing, overwhelming injustice. Otherwise, there’s really no meaning to the story. The Beast is okay because he isn’t “really” bad and her being held captive against her will is okay because she isn’t “really” being held captive.

Which, if that’s the case–then who cares whether she goes or stays?

For those of you who’ve read my other work, you know that I’m not a fan of pat explanations.

I still think that this story is, at heart, a romance. It’s a story about rescue, redemption, and what it means to start again. About the transformative power of forgiveness, to both the forgiver and the person being forgiven. But Belle’s romance isn’t with her fantasy of a perfect life, or with the myriad freedoms that a cash-filled wallet supposedly brings, but with a man. A real man, with real flaws. A man whose “beast” is more than skin deep. As the original Beast’s was.

Back in the middle ages, fairy tales served a definite purpose. Stories about “the troll under the bridge” served the same purpose as warnings about strangers offering to show you the puppy in the back of the unmarked panel truck serve today. Calling an erotic romance a retelling of Beauty and the Beast isn’t stunt casting; it’s my attempt to infuse the story with the same obvious relevance, the same visceral urgency that it had in its infancy. To take “my father made me marry this man, so he could pay off his debts” and transform that idea into its modern equivalent. An equivalent that needs no translation, that’s immediately understandable, because this is a story that reflects, and has always reflected, the injustices that all women to some extent face.

Belle wasn’t a meek, “love him better” type but a crusader for justice within her own world and in her own time—and I wanted people to see that, when I gave her a modern voice.

Coming Soon: The New Guide

Self Publishing Is For Losers is getting both a rerelease and a new branding: as Indie Success. The old title, we felt, left something to be desired in terms of conveying the seriousness of the advice inside. It was tongue in cheek to us but, ultimately, insulting in its insinuations to some others. Indie Success: From Dreamer To Established Author In One Year is much more descriptive. There are some updates to the information inside, as well.

What I’d really like to know is, going forward, what information isn’t covered in this book and in its companion volume, I Look Like This Because I’m A Writer, that you, my readership, would like to see covered? I ask because I’m considering the possibility of a third volume in this series (which may or may not, if anyone’s interested, cover such topics as rebranding). Let me know–your suggestions, and what you think in general–in the comments!

October 20, 2015

The Myth of the “Publishing House”

What follows is an excerpt from Self Publishing Is For Losers, a guide I wrote last year to the world of indie. I’ve participated in a number of discussions, lately, with people who were signing their rights over to “publishers” in exchange for a feeling of legitimacy. And that saddens me because, the fact is, unless you’re signing with the Big Five–and we all know, by now, that I chose not to–you’re getting a raw deal. And even then, there’s an argument to be made that you’re getting a raw deal. You don’t need a publisher, of any kind, to have the exact same online visibility as your traditionally published counterpart and unless you’re under the Random House (or Hachette, etc) umbrella you’re not doing yourself any favors on the print distribution side either. All you’re doing is giving away your rights, and hard-earned cash, in the name of vanity.

When You Self Publish, Who Is Your Publisher—Really?

There’s some confusion about this issue.

In general, there are a lot of misconceptions about what self publishing is and isn’t. For example, many aspiring authors erroneously believe that self publishing means no actual, print book. Others believe, mainly because they’ve been told so by unscrupulous so-called “publishers,” that they still need to sign with a publisher of some kind in order to see their books in outlets like Scribd, Kobo, and Barnes & Noble. Still others believe that professional cover art, or professional marketing and publicity services, also require a publisher.

None of this is true.

In this section, we’re going to look at the nuts and bolts of the publishing process. What it is, and what it isn’t. What you definitely need to pay for, what you never need to pay for, and what you should probably consider paying for anyway. From finished manuscript to paperback, there are a lot of steps—and a shroud of mystery surrounding those steps, both encouraging and reinforcing the idea that the publishing process is somehow magical.

It isn’t.

The first issue we’re going to tackle is a seemingly simple one, but one that’s nonetheless caused a lot of heartache for a lot of writers because it’s so misunderstood. When you self publish, who is your publisher—really? You might publish under your own name, or you might publish under an imprint that you’ve designed, but you’re not the one actually writing the code that allows your book to appear on Amazon, or packaging and shipping that book (or delivering it electronically) all over the world.

The short answer is that if your e-book appears on Amazon, then your publisher is Amazon.

And if your e-book appears on Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Scribd, Oyster, or in Apple’s iBooks store, then your publisher is Smashwords. Because once you upload your e-book to Smashwords and it’s approved for their premium catalogue, you can choose to have your book made available through all these venues. And if your actual, hold it in your hand paperback is for sale through Amazon, or Barnes & Noble (either online or in stores), then you’ve published that edition through a print on demand service like CreateSpace.

All of these platforms are free to join, with no upfront costs. Rather, they get paid when you do. Out of every book sale, they take a specified cut that you agree to upfront, with each individual platform, when you choose to publish with that platform. Your agreeing to that cut is your signing a contract with that platform; the platform is your publisher.

For example, I sell all of my books on Amazon for between 2.99 and 4.99. Unless of course they’re free; sometimes, for various reasons, I run promotions wherein they’re free. When I’ve written a new book and it’s ready for publication, I upload it to Amazon and enter in my price point. I then choose that I want the 70% royalty option. What this means is that for every book sold in every market where the 70% royalty option is available, I’ll earn 70% of the 2.99 I’m charging. Which means that Amazon, in exchange for doing the hard work of exposing my book to a wider audience, gets a cut of 30%. That’s their cut of the profits. I’ll talk more about royalties, profits, and how the pie slices later on, but for right now the main take-away should be that the deal you’re brokering with Amazon mimics the deal you’d be brokering with one of the Big Five.

Only on much more advantageous terms to you.

The term “contract” confuses some people, especially if their only familiarity with the term comes from John Grisham thrillers. They picture contracts as being sheets of paper, or even reams of paper, with the word contract printed in bold letters at the top, and the signing of a contract only something you do in lawyers’ offices or perhaps the occasional car dealership. But the truth is, we enter into contracts every day. When you make a pit stop at McDonald’s, you’re agreeing to pay a set fee and in return receive the food of your choice. That’s a contract. When you agree to the terms of service on a new software bundle, you’re entering into a contract.

This isn’t legal advice and if you need legal advice, then you should consult with an attorney. Each situation is different and laws vary by jurisdiction. But at the same time, it’s important to know what a contract is. In philosophical terms, if nothing else. A contract, in its simplest form, is a meeting of the minds. An agreement, wherein the parties involved understand what’s happening and are agreeing to the same thing. There doesn’t need to be fancy paper or, depending on the situation, even your signature; your consent, even sometimes your implied consent, is enough.

Knowing this, you can better understand your relationship with Amazon. And better evaluate whether, in addition to Amazon, you also need a so-called “publisher.” Although the more honest term for such outfits, and the term I prefer, is “publishing facilitator.” If you’re publishing on Amazon, then you don’t need a separate publisher; anyone with a book and a dream can upload their book this morning and be selling copies by this afternoon.

You might need the help of a professional to format your book, or to design you a cover, but these are services that you can purchase a la carte from all over the internet. You don’t need a separate publisher to help you with that; all you need is a valid credit card and the ability to clearly and effectively communicate your desires. The same is true with everything from editing to advertising to publicity—you can pay for it, or not, as you choose.

And yes, I’ll talk more about that later. But for right now it’s important to understand that while all of these services are valuable, or can be valuable, depending on your personal goals and, of course, your budget, none of them are publishing. When Random House purchases the services of an illustrator, for example, they’re sending an individual person, an employee of Random House, to do business with that illustrator. You can do the exact same thing. You do not need a separate publisher, or someone calling themselves a publisher, to access any of the services that are provided to their authors by the Big Five.

Unfortunately, people don’t know this, and that’s where unscrupulous outfits come in.

I can’t tell you how many writers I’ve talked to, who told me that they’d signed with “publishers” to get their books on Amazon; or that they needed a “publisher,” in order to sell at Barnes & Noble or Kobo. Some of these authors were paying hefty fees, too: 50% or more of their royalties. And they defended that to me, explaining that royalties were simply part of the game. They were right, of course, on one point: that royalties are a fact of life for all authors. But they were wrong about the most important point of all, which was that they were getting something for their money—something above and beyond what Amazon, or Smashwords, was giving them in return for their cut.

Traditionally published authors receive royalties from their publishers, yes; which doesn’t mean that, therefore, self-published authors should also be paying a cut of their profits to their “publishers.” What is, in essence, paying twice for the same service. A traditionally published author through, say, Hachette is going to let Hachette keep a cut of every book sold; because he isn’t also paying Amazon. Hachette is his publisher; not Amazon. But if you’re uploading a book to Amazon, and it’s being made available for sale through Amazon, then Amazon is your publisher. There’s no reason to pay someone else half of your earnings for the privilege of having them use a web page on your behalf.

So what’s the appeal of these outfits, then?

I think it lies in the fact that, in many minds, there’s still a stigma surrounding the idea of self publishing. The publishing world is changing rapidly and it’s going to take everyone awhile to catch up. So while self publishing is objectively the best route for most writers, with reams of ever-improving statistics to show as much, there’s still this lingering belief that self publishing equals failure. That no one can, or should, take you seriously as an author if you self publish because self publishing is the last resort of the truly talentless—and desperate.

So-called “indie” and “niche” seem to represent the best of both worlds: an accessibility not found with the Big Five, but the legitimacy of having someone else’s name on your spine. You’re not just Joe Q. Public, entering the market all on your own. You have a team behind you, which makes you a real author.

At least, that’s the theory.

And there are smaller publishing houses that legitimately do their job. More common are outfits like Evil Toad Press, which provide a la carte services for self-published authors and thus allow them to compete with the “big boys” in terms of cover design and so forth. But legitimate outfits are few and far between and, for the most part, they’re charging you to do something that you could easily do for yourself. And the fact that they’re not telling you that you could do it yourself should be the biggest red flag of all.

But specifically, when it comes to evaluating the host of publishing facilitators out there, watch for the following.

First, someone who tells you that you need a publisher, separate from Amazon, to have an imprint. This is not true. When you publish with Amazon, you have the choice to include your own imprint. Which can be anything you decide, so long as it’s not misleading (i.e. no calling your one man indie outfit Random House). We came up with Evil Toad Press and the corresponding toad logo during a group pizza eating session.

When I upload a new file to Amazon, I tell them (truthfully) that the publisher is Evil Toad Press. How? By typing “Evil Toad Press” in the box on the form that asks for my publisher.

If you want fancy graphics, then you can design them (we designed our own). Or pay someone else to design them for you. But you don’t need fancy graphics, or to spend a single nickel, to create your own imprint. All you need is your imagination.

Second, someone who promises to “distribute” your work to Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, and so forth. When you publish with Amazon, Amazon is also your distributor. That’s just part of the package. Amazon does the hard work of “shelving” your book within its online store according to your specifications, of making it available for sale, and of either making your e-book downloadable when purchased or shipping your actual physical book to its new owner’s address. Likewise, when you publish with Smashwords, Smashwords is your distributor: to Barnes & Noble, and all the other outlets with which Smashwords has preexisting agreements.

My printed books are for sale via Barnes & Noble, on their website and in a few stores. My e-books aren’t, because my e-books are all enrolled in Amazon’s Kindle Select program. This is because I publish my printed books through the print on demand service, CreateSpace. CreateSpace, which is an Amazon company, acts as my distributor by creating this link with Barnes & Noble. Barnes & Noble, and special magic powers, have nothing to do with it. CreateSpace has a preexisting agreement with Barnes & Noble to distribute its premium catalogue through Barnes & Noble’s website.

As far as actual brick and mortar stores, unless you’re Stephen King the determination of whether to carry your book is made for the most part on an individual store-by-store basis.

Moreover, it’s important to remember that readers can special order any book with an ISBN through any bookstore.

Third, someone who charges you more than a 15% cut. Unless your publisher is absolutely, provably doing something for you that you could not do on your own, your publisher is essentially acting as an agent. Agents take a 15% cut. Anything more than 15% is usury. And, to be honest, I’m not a fan of royalties in this situation at all. I feel that purchasing a la carte services, up front and for an established fee, is the far more fair and honest method of doing business. I’d always rather know exactly what I’m getting, in exchange for cold hard cash, than possibly sign away too much in exchange for vague promises. Promises that may or may not be kept.

Fourth, someone who claims to offer “direct” as opposed to “third party” distribution through outlets like Amazon. Or Barnes & Noble, or any of the other outlets accessible through the Smashwords platform. Such language is disingenuous at best. The so-called “publisher,” in this case, is the middleman. “Direct” would be if you, the author, were interacting with Amazon without his services. He’s insinuating himself into a situation that doesn’t need him, by telling you that you need him, in the hopes of skimming your profits.

Fifth, someone who tells you that you need a publisher in order to create a print book. You don’t. There are a couple of popular print on demand platforms; in this guide, I focus on CreateSpace, which is an Amazon-owned company and probably the most popular. Their work is top notch, too. And they offer their own design services, if you’re not interested in purchasing those design services elsewhere but instead want one stop shopping.

Sixth, someone who charges a percentage of your royalties, but who also expects you to pay out of pocket for other expenses—for example, for cover art or marketing. The entire point of charging a cut in the first place is that you’re not charging other fees. When you’re traditionally published, your publisher’s cut is what’s supposed to cover the expenses that the publishing house incurs on your behalf: for example, editing. Cover design. Whatever. Anyone who keeps asking you for money, without very clearly explaining—and being able to prove—where that money is going is scamming you.

So, in closing, there’s only one thing to do if you encounter anyone like this: run.

They might need you, but you most certainly do not need them.

Now, what might seem like a tedious explanation of who’s who is actually extremely important, because the more you know about your role in the publishing process—and what the publishing process actually is—the better equipped you are to act in your own best interests.

It’s a daunting prospect, to be sure, but you have to. Particularly as an artist. Because the sad fact is that nobody else will. You have to learn to be your own best advocate, which first and foremost means getting informed. And not by the same people who have a financial interest in convincing you that you need them. Other people, personally and professionally, are only ever going to treat you as well as you treat yourself. Which means that you can’t evaluate how other people are treating you, at least not meaningfully, unless and until you get a handle on what treatment you actually deserve.

Authors: You Are Not Amway Salespeople

I’m too young to remember this commercial, but it sums up the theory behind multi-level marketing perfectly: you’ll tell two friends, and they’ll each tell two friends, and so on and so on until the whole entire world has had their hair transformed by this magical (now defunct) shampoo. What could be simpler or more incredible? Buy yours today, and by “buy yours” I mean join the sales movement of the future! Now, why MLM’s are doomed to fail is another topic for another day because today, we’re focusing on the micro rather than the macro: specifically, how treating your book like it’s the latest miracle fat loss wrap, shake, etc is going to torpedo your writing career and lose you all of your friends.

All MLM’s, whatever products they’re supposedly about, are really all about one thing: a dream. And you make your dream come true, according to the various seminars, coaching sessions, pamphlets, etc, that they all seem to have, on the backs of your friends. By taking advantage of their friendship. See, it all starts with them forking over their hard-earned money to buy your new car product. Then, they love helping to pay your bills your product so much that they join your team. And then they repeat the whole sorry process over again, with new people. It’s called the “downline.” And it’s a strategy that makes sense, in theory, at least to some people.

Unfortunately it fails to consider the first maxim of business, which is what’s in it for the other guy? Why would someone want to first buy your product and then, secondly and more importantly, how is buying a product supposed to transform into having any desire to then turn around and sell it? I go out for coffee almost every morning; I’ve never felt the urge to become a barista and Starbucks offers great benefits. For most of us, buying our friends’ wraps, bags, etc is an act of guilt. Whose favorite brand is at a house party, and not at Nordstrom?

I’m going to point out here that I’m much more likely to buy something from someone if I know they’re just looking to make a little extra cash–by only selling the product. One of my best friends sells a few of these things, but she’s not looking to sell me “the dream.” Which, contrary to what everyone else plaguing the internet with “opportunities” seems to think, makes her actual opportunity (to own a purse) a whole lot more appealing.

Conversely, it seems like half the (other) people in my newsfeed (on Facebook, on Instagram) are bent on convincing me to halt my life and sell something. Which is sad for two reasons–and this is where, incidentally, we begin to get into comparing this to writing. First, it’s not the greatest thing in the world to feel like your “friend” sees you as a commercial opportunity. Because, let’s get real here: you are the “opportunity” these MLM’s are touting to their adherents. The entire business model is built around preying on ties of friendship in one manner or another. And this…might sell a few products now and then but, when done according to program, it also ruins friendships. If you stick to the kiddie pool, like my friend, you’ll retain all your friendships (she’s stuck with me until one I die and then I’ll come back to haunt her) but you won’t be driving the pink Cadillac.

Second, it’s all for nothing. Even if people are willing to use their friends like tools, no one has enough friends. To illustrate, I’m going to put this into book terms. Using myself as an example, because airing someone else’s dirty laundry would be rude. I make a fairly decent living as a writer. Currently. But, I mean, I’m hesitant to say that because royalties–regardless of what various MLM promotional videos and, indeed, Drake videos would have us believe–are a craps shoot. In order to make this fairly decent living, though, I have to sell at least fifty books per day. Every day. That’s 18,250 books per year. Which means that even if some people buy my complete catalogue (which they won’t, because someone who buys, say, the omnibus edition of The Prince’s Slave probably isn’t going to also buy each of the three original volumes in the series), most purchases are discrete purchases.

Most customers are unique customers.

Even if everyone I knew bought a book, even if everyone I knew bought all of my books, that would still account for, at most, a week’s worth of sales. And then what? According to the MLM-style method of “use your friends to make a quick buck,” I’d then have to start hounding them all to “each tell a friend,” and get them to buy my books. As many of them as possible. And pretty soon their enjoyment of my books–and of me as a friend–would be gone.

It’s impossible to generate the kind of sales volume you need, to survive–at anything–using this method. Which is why, grandiose promises of “opportunity” aside, you’ve never actually seen anyone pull up to one of these recruiting events in a Ferrari. So the question becomes, why do authors do this? The same authors who wouldn’t be caught dead hawking Mary Kay?

Because, I think, greed puts blinders on us all. The question we should all be asking ourselves, before we find ourselves obsessing over a new sales strategy, is this: who do I know, or know of, in my real life, who utilizes this strategy successfully? Who is my real life role model?

It’s easy to evaluate something on the strength of promises. It’s supposed to be easy; that’s the idea. It’s a lot harder to evaluate that same something on the basis of facts. Because facts, quite naturally, don’t paint as rosy a picture. Sitting down and actually figuring out, “this is how many people I’d have to have working for me, and this is what targets they’d have to hit” will never be as alluring as fantasizing about in ground pools. And people know this. Other people. The people taking your money. As a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed MLM distributor–or as an author. You know, all the people out there promising to promote and, in some cases, “publish” your book. They’re not offering their advice, or services, out of the goodness of their hearts. If they were, they’d be doing so for free.

So the real question becomes, not, does what this person is promising sound good but, has anyone else actually built a successful career, as an author, by following this program?

Too many authors treat their friends like potential downline recruits. They post constantly, on Facebook and Twitter and everywhere else, about “buy my book.” They make a big deal, constantly, about how they’re an author and blah blah blah. It’s not making them rich and so, instead of reevaluating their strategy, they push harder and harder. Just like my friends who sell [insert stupid product here] do. Until their friends feel like they’re being squeezed for every less drop.

You have to realize that, as an author, the vast majority of your sales will be to strangers. And plan accordingly. There are other means, and much more effective means, of getting your book out there that leave your friends, family, and everyone else you know in “real” life completely out of the picture. Facebook pages (public, not personal), blogs. Pitching the idea of carrying your books to your local Barnes & Noble. The list is long, and varied. And mostly consists of things that cost only hard work. Which, in the final analysis, is really the sum total of the “secret.” To success in this field, or any.

Thoughts?

October 17, 2015

Don’t Read This Book

Because dismal, torpid examinations of colonial era politics aren’t everyone’s cup of tea, don’t read by far the least popular thing I’ve ever written. Don’t bother to discover, on your own, why everyone else hates it. Just take for granted that they do, and with good reason. This is, without a doubt, the most wearying book you’d ever read. The tears of lemurs are as lemon drops in comparison. Bright moments of joy. Wherein there is no joy in this series. Only war. And angst. People who don’t like each other. Women whom critics have called, “unlikeable, preachy, and judgmental.” Because they stand up for themselves too much. And sex. There’s sex, too. Challenging, difficult to read about sex, often involving multiple people. But don’t get sidetracked: underneath the sci-fi surface layer drivel, mainly this is a book about the angst, material and existential, that was life under the British Raj. Spoiler alert: it was terrible.

October 10, 2015

The Audiobook is OUT!

Have you listened to The Demon of Darkling Reach on audiobook yet? You can find it on Amazon, Audible, and iTunes. I love how our narrator, the talented actress Shiromi Arserio, brings the story–and the characters–to life. And, if it looks like the audiobook is popular, and this is something you, the reading public, enjoy, my publishing powers that be will consider footing the bill to audio-ize the rest of the series (and potentially other books, from other series, as well).

Let me know what you think in the comments!

October 9, 2015

The Prince’s Slave: FREE for the Last Time in 2015

Because you know you want to.

Read an excerpt here.

Read the first five chapters here.

And download your copy, for free, today (Friday, October 9) and tomorrow (Saturday, October 10), to your Kindle or to any electronic device, using Amazon’s free Kindle app. Never be without what may be the first erotica-horror hybrid in your library. Or, indeed, without any of the other millions of books available for immediate download, right now, from all your favorite authors. Some are free, some cost less than a Pumpkin Spice Latte. All have fewer calories.

October 7, 2015

The Black Prince Update 6

This morning, I’m finishing chapter twenty-seven of The Black Prince: Part II.

Part I is complete. Part II, as of this morning, is almost half complete. Both are full length novels, or will be, when complete, well over 100,000 words. I cannot tell a lie, the notion of completing this manuscript on time is a little daunting. Especially considering everything else that’s going on. I don’t have a kitchen right now, as ours is under construction. Struggling downstairs in the morning, only to realize that of course there’s no coffee maker in your kitchen right now because there is no kitchen, isn’t a treat. But really, that’s also the least of things. First world problems, however vexing, are still first world problems. We are also experiencing some other issues, as well. Mostly with extended family. And yet, one goes to work every day. That’s the program.

All that being said, I really am quite pleased with how the manuscript is coming out. This has been an exciting story to tell and one that, at times, has had a great deal of me in it; but I’m also excited to finish it, and move on. But tell me, fearless readers, what’s your favorite thing about the series? What are you most anxious to find out? Who’s your favorite character?

October 1, 2015

“Do Better Research Next Time”

A reviewer writes:

“The story was ok, the characters felt kind of sterile to the end. but the worst thing the quasi non-existent research on the places where the story takes place, instead you get served American presumptions about Eastern Germany and Europe. Dear PJ Fox, even before 1990 cars were a common thing in Prague, even more so later. and There Is No Such Thing as a so called “Modern Cinema Building” from the “communist” past in Dresden. First, no communism; Second, the cinema in question is probably the so called “round cinema” (round cinema) in the city center. It Should not be so hard finding this out over the internet, Should it? There are even people living in/coming from Those above Mentioned cities, WHO You Could ask.”

To which I reply: first, it’s called an unreliable narrator.

And, second, please open a book.

You first learn about Dresden, and Prague, from the perspective of a teenaged American with a limited education. She describes things as she sees them; and no, she doesn’t have much of an appreciation for communist-era architecture. And yes, cars do occupy a different role in German life (which is what she’s remarking on). Also, you can see a picture of the nonexistent cinema building online, just google it. But just like the average Amazon reviewer apparently doesn’t know that America–all of America, but especially rural America–really is different from Germany, Belle is a little mystified by her new surroundings.

Just like I’m a little mystified by how anyone could refer to Dresden and “no communism” in the same sentence. Dresden has recovered somewhat since the bombings of 1944, but East Germany, of which it ultimately became part, was certainly communist. Belle might not have an encyclopedic knowledge of Germany, past and present–that would be poor writing, if I used a girl from the sticks to teach the reader about a culture that was supposedly completely new to her–but she did pass junior high social studies.

Dresden’s past is discussed, very briefly, in terms of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Perhaps this reader feels I should attend the University of Google for that “myth” as well. Or maybe she feels that my lack of knowledge is revealed most clearly in my lack of random capitalization and nonsensical punctuation. For surely those things invoke, like nothing else, respect for one’s fine classical education.

Pictured: a figment of my imagination.

Moreover, a thing can exist, or it cannot. According to Nagarjuna, “things derive their being and nature by mutual dependence and are nothing in themselves.” He believed, as do modern Buddhist scholars, that nothing truly existed. In other words, referring to the quote above, whether one perceives a thing as good or bad depends not on some intrinsic quality in that thing but on one’s attitude. What breakfast to the spider is chaos to the fly. And thus we return to the concept of an unreliable narrator. But even in less philosophical terms, there is no such thing as “quasi non-existent.” Quasi is a compound word of qua and si, from the Latin, meaning “resembling.” But a thing cannot resemble nothing; nothing has no characteristics to resemble.

Putting aside this person’s grievance that I did not pay her to be my fact checker–or, indeed, copyeditor–I only write about places I’ve been. It’s interesting, though, the various nationalities, experiences, and education levels attributed to me. Those who wish to know are free to ask, rather than assuming, as well. But maybe I could somehow facilitate a meeting between this person and the one who didn’t know where or what India was. I can only presume that this particular reviewer didn’t read far enough into the book to notice that it portrays an interracial romance, because then she’d have had that to be horrified about, as well.

As this–the history of Dresden, as well as what buildings can be found there–is one of the few things on which my Top New England University and Google can agree, I’ll have to chalk it all up to this disgruntled reader being even younger than I am.

I wonder what part of the States she lives in.