Aidan Moher's Blog, page 10

February 18, 2015

Cover Art for The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers

My, my, my.

Many things could be said for of Becky Chambers’ The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, a self-published success story that Jared Shurin of Pornokitsch described as “a joyous, optimistic space opera […] progressive but not worthy and filled with warm and endearing characters”, however, the original cover art – which could be lauded for its enthusiasm, if nothing else – was not a showstopper. So, alongside a new publishing deal from Hodder & Stoughton and a Kitschie nomination for Best Debut, comes a gorgeous new cover for Chambers’ debut. Isn’t it just lovely?

The crew of the Wayfarer, a wormhole-building spaceship, get the job offer of a lifetime: the chance to build a hyperspace tunnel at the centre of the galaxy. The journey will be time-consuming and difficult, but the pay is enough to endure any discomfort. All they have to do is survive the long trip through war-torn interstellar space without endangering any of the fragile alliances that keep the galaxy peaceful. But every crewmember has a secret to hide, and they’ll soon discover that space may be vast, but spaceships are very small indeed.

“I fell in love with Becky’s universe the moment I started reading The Long Way,” Anne Perry, Chambers’ editor at Hodder & Stoughton, said after revealing the deal on the publisher’s official blog. “The world she creates is warm and wonderful and so involving that I found myself resenting any time spent not reading the book. I was thrilled to learn about the Kitschies shortlisting so soon after agreeing the deal with Becky – The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet is an incredibly assured debut and I am absolutely delighted be working with her at such an exciting moment in her career.”

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet will be released by Hodder and Stoughton as an eBook on March 16th, 2015, followed by a hardcover release August 13th, 2015.

The post Cover Art for The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

February 17, 2015

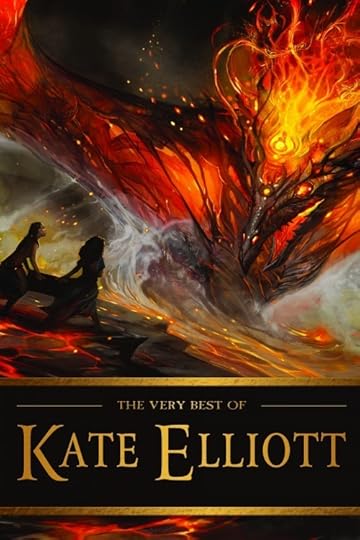

From Sketch to Final Cover: The Very Best of Kate Elliott

Buy The Very Best of Kate Elliott by Kate Elliott: Book

In a post last year here on A Dribble of Ink, Aidan kindly debuted the stunning illustration Julie Dillon painted of a scene from my novel, Cold Steel. In that post I mentioned how the commission came about:

When I decided to commission an artist to illustrate a short story in the Spiritwalker universe, I was thrilled that Julie Dillon agreed to work with me…

Besides the black and white drawings for The Secret Journal of Beatrice Hassi Barahal, I also asked Julie for two color illustrations. I picked the subjects based on passages from Cold Steel that I thought would be visually evocative.

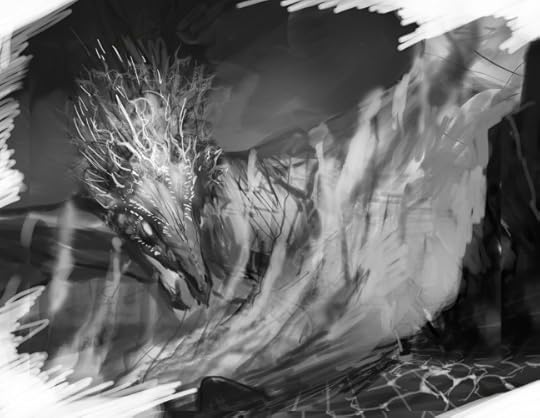

I particularly wanted an illustration for a scene in which the heroines, Cat and Bee, emerge from a cave onto a beach whose strand, instead of sand, is “red coals and smoking ash.” Here in the spirit world the sea isn’t water; it’s smoke. In the scene a dragon rises out of the sea of smoke to confront them.

A bright shape emerged, smoke spilling off it in currents. The dragon loomed over us. Its head was crested as with a filigree that reminded me of a troll’s crest, if a troll’s crest spanned half the sky. Silver eyes spun like wheels. It was not bird or lizard, not was it a fish. Most of its body remained beneath the smoke. Ripples revealed a dreadful expanse of wings as wide as fields, shimmering pale gold like ripe wheat under a harsh sun.

Julie sent me an initial sketch for my approval, and I was astonished by the dramatic sweep and expansive line.

Later she polished up that black and white sketch for me to use as one of the 29 sketches in The Secret Journal.

I was pretty impressed with the sketch but the finished color illustration blew me away. Her use of light is phenomenal. The dragon looks both ephemeral–made of smoke and flame–and yet also terrifyingly powerful.

Therefore, when Tachyon Publications approached me about the possibility of publishing a collection of my short fiction (now available as The Very Best of Kate Elliott), I asked if they would be interested in using this illustration for the cover. They politely agreed to look at it, making no promises that it would be suitable, right up until the moment they saw it. At that point they were, understandably, quite enthusiastic.

Not every illustration or photo can be used on a book cover because the dimensions and balance have to work together. Furthermore, using the wrong typeface, color, and design can ruin an otherwise interesting image. Designer Elizabeth Story did an incredible job turning the illustration into a gorgeous cover. She flipped the image (my daughter, also a designer, explained why the image works better flipped on a book that opens on the left; it has to do with the way the eye gets drawn to the right and thereby to the side of the book you open). The clean, classic typeface doesn’t clutter, nor does it draw attention to itself and away from the image. The gold color of the letters echoes the fire in the dragon.

Watching art take shape fascinates me, whether seeing a story go through multiple refining drafts or observing as a sketch turns into a finished book cover. That the illustration so magnificently captures a scene from one of my own novels is just the icing on the cake.

You can buy prints of the color illustration at Julie’s INPRNT store.

The post From Sketch to Final Cover: The Very Best of Kate Elliott appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

February 16, 2015

“Austentation” by Adrian Tchaikovsky

Guns of the Dawn is set in a fantasy world: there are wizards, there are sentient non-human races, the names of the nations are all fictitious. At the same time, Guns is far more of an ‘echo history’ than Shadows of the Apt was 1. Specifically, the world and time of Emily Marshwic and her peers is a distorted mirror of Regency England, the start of the 19th century and the Napoleonic war. There are other strands in there – something of the English Civil War, something of the American War of Independence (for it is a war story) – but the Regency thread is by far the strongest.

It’s probably a load of nonsense to claim this period as ‘The Rise of the Novellists’. Still, looking back via the truncated view of time our perspective allows, it’s tempting to make an argument for it: new readerships amongst new demographics, new types of story being told. It’s not just Austen (writing very much in the moment, with Pride and Prejudice out in 1813), Shelley’s Frankenstein was first seen that same year – perhaps it’s that this is when women novellists really seize the public imagination for the first time? I’m not enough of an academic to make the case, and there were certainly women writers before this 2, but you could argue that expanding middle-class readership meeting aspiring female authorship created a sweet spot that led to this flowering of fiction. The age of Napoleon and Prince George is one that has been chronicled in an intimate way past ages were not. It has lodged in the literary subconscious, to be turned and re-turned, both within living memory of the events (Tolstoy, say), and far later (Cornwell’s seminal Sharpe books of course).

There has been something of an Austenian revival amongst genre

writers.

There has been something of an Austenian revival amongst genre writers. Aside from the well-trodden zombies element and PD James’ murder mystery, fantasy writers have found much to love there. Novik gives us the military spectacle of Temeraire, history tweaked out of line by the presence of vast dragons that do battle like ships of the line. Two years before, of course, was Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (now being filmed, because it’s a period the cameras love as much as the writers).

What is it that makes the age of Austen and Napoleon so attractive to the fantasy writer particularly? It’s certainly not the only period that gets such treatment – the Steampunk revolution has thrust the other end of the 19th century more into the limelight for sure – for better or for worse, in fact. Both periods have something of the same opulence for the rich – the gorgeous and elaborate costumes, the decadence and ennui and delicious vice – whilst having a satisfactory level of picturesque squalor for the poor. Perhaps the Regency period is both more colourful and less squalid (with the industrial revolution yet to properly revolve), though. Certainly the unsettling socio-political element of a lot of steampunk is less evident – if your story is set in England (or some place like it) and you have Napoleon breathing down your neck, it’s easier to tell a story about heroism against the odds than if you have the ironclad might of the British Empire (and its steam-dreadnaughts) backing you up.

Buy Guns of the Dawn by Adrian Tchaikovsky: Book

The Regency period is a perfect balance point to tell stories about war and peace

Austen and Napoleon, though: I think this is one of the great hooks of the period. Because of writers like Austen we have preserved a picture of the everyday lives of the time – men and women for whom the history-book events of the age were only a backdrop to their personal stories. At the same time, the Napoleonic wars were one of the very last flourishes of the old world, in the face of an all-encompassing modernisation which would give us the Great War within a century, and plenty of wars in between. Bright uniforms and social divides, salt of the earth soldiers, folk songs, Polly Olivers, cavalry charges that weren’t doomed from the start (the Light Brigade wouldn’t start their charge for forty years or so). The Regency period is a perfect balance point to tell stories about war and peace 3 – those who fight, and those who stay at home. The wealth of existing literature, the songs, the correspondence all serve to paint this relatively brief flowering of time in sufficient detail for we later writers to crib from and tell all manner of stories.

The post “Austentation” by Adrian Tchaikovsky appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

February 11, 2015

Chatting with Michael J. Sullivan about his half-million dollar deal for The First Empire

Michael J. Sullivan is one of fantasy’s most prominent self-publishing success stories. His debut series, the Riyira Revelations, sold 90’000 units before Sullivan sold the publishing rights to Orbit Books in 2011. Since then, he’s been a poster boy for Hybrid Publishing, an approach that allows authors to leverage the strengths of both the traditional publishing model and self publishing to their advantage and the advantage of their readers.

Yesterday, Sullivan announced that he’s sold The First Empire, a new epic fantasy set in the same world as the Riyira Revelations to Del Rey. The deal includes the first four volumes of the series: Rhune, Dherg, Rhist and Phyre. I caught up with Sullivan to chat about the new series and his half-million dollar deal.

“The First Empire series is based in the same world as the Riyria books, but it takes place several thousand years in the past,” Sullivan told me when I asked what the new series had to offer old fans.

But, you don’t have to be an entrenched fan to be excited about Sullivan’s new series. “It’s designed such that readers won’t need to know anything about Riyria, so it should appeal to both new and existing readers. That being said, for those that have read Riyria, they’ll learn that certain aspects of Elan’s past aren’t exactly true. I’m enjoying exploring the differences between myth and reality, and hopefully that exploration will be fun for existing readers as well.”

Sullivan spent years working in the world of Elan, the setting featured in The Riyira Revelations, and had to shift into a different mindset when it came time to delve into its history for The First Empire, to explore the origins of magic in his world. “That part was easy because I had already done it when writing Riyria,” Sullivan said.

“Before I started those books, I had a history of Elan going back 8,000 years. I had extensive notes about the various classes and technology and knew that magic was much more prevalent back then. An important plot element of The First Empire is showing what happens when magic enters into the world, and how it disrupts the power structure. I did all that as background for Riyria, but most of it never appeared on the pages of those books. So, for the new series, all I needed to do was to tap into that existing cannon. For me, it was nice to see that stuff I had previously come up with have its day on the stage.”

Sullivan first made a name for himself among fantasy fans when he self-published The Riyira Revelations to much financial success before signing a more traditional publishing deal with Orbit Books However, The First Empire is being published not by Sullivan but from an new traditional publisher: Del Rey. What prompted this switch?

“I’m a huge fan of self-publishing and know very well about how financially lucrative it can be,” Sullivan admitted, addressing the surprising move to a new traditional publisher. “For my traditionally published works, my reason for signing has always been to take my career to the next level.”

While happy with Orbit’s dedication to the Riyira novels, Sullivan recognized that their vision for his next series was diverging from his own. “I think Orbit did a great job with The Riyria Revelations, and it has made both of us a lot of money, but I saw The First Empire as an opportunity to raise my profile yet again. To that end, I had one requirement, which was to release in hardcover. Orbit didn’t agree with that vision. Fortunately, the other publishers making offers did. Trying to do a hardcover release through self-publishing wouldn’t have been easy, but if none of the publishers agreed, I was prepared to do exactly that.”

And the new book deal, a “major deal” from Del Rey covering four volumes of The First Empire series, is no slouch, either. Sullivan is set to make a minimum of $500,000 for the book/eBook publication, and another $100,000 – $250,000 in a separate deal for the audiobooks. Those are major numbers. “The term ‘major deal’ comes from the deal categories used by Publisher’s Marketplace,” Sullivan explained. “It’s more of less the industry standard for talking about publishing advances in ‘broad terms.’ The ‘major deal’ category is the highest there is and represents deals that are at least half a million dollars.

The ‘major deal’ category is the highest there is and represents deals that are at least half a million dollars.

“Beyond that, it’s also a major deal for two other reasons. First, Del Rey felt strongly enough about the series to offer a 4-book deal. In general, they prefer not to go beyond three books so this speaks volumes about how they feel about the series. Secondly, the deal was a preempt which means a high bid meant to prevent opposing players from bidding. When Del Rey’s offer came in, I didn’t need to see any more offers. I already had a) the publisher I wanted and b) an offer that I thought respected both me and my work. Even if someone else came in higher, it wouldn’t have changed my mind.”

Sullivan adheres to a rigorous writing schedule, drafting out the entirety of the series in manuscript form before selling even the first book. “Like Riyria, I want to write the full series before publishing the first book, and I expect to have the fifth and final book finished in April or May,” he said. “I’ll need some time to make some minor modifications to the first book based on things that have happened in the last one.” Sullivan is nearly done writing the fifth and final book in The First Empire, but don’t let that fool you into thinking a release date for the series is just around the corner. “The full details of that still have to be worked out. So far, we have been talking about releasing Rhune in the summer of 2016.”

What does that mean for the rest of the series? Sullivan says the details are still being worked out. As for the subsequent books, I don’t know the exact spacing. What I do know, is it won’t be the same way Orbit did them. For one thing, books #2 – #5 have to go through a full editing cycle. The “alpha read” can take several months and at least a month to implement the changes. Plus I have to incorporate changes based on things that occur later in the series. Then the “beta read” starts, and that is a three-month cycle (at a minimum), and then finally it can go to Del Rey for their editing. So while all the stories are written (or soon will be), there is still a lot of work to take them from manuscript to final book.”

Sullivan understand the pressure to publish on a regular schedule, so he has a few other projects on the back burner to fill the time, including a sequel to Hollow World and more Riyira stories. More news about the publication schedule will be available once the ink dries on Sullivan’s new contract with Orbit Books.

The post Chatting with Michael J. Sullivan about his half-million dollar deal for The First Empire appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

February 10, 2015

No More Avatars

We live in a world of fast-moving moral panics. A world where information moves literally at the speed of light, crossing oceans and wrapping the world in mere moments. Technology connects us all, but it is also a tool, willing or unwilling, that embeds in us a fear of the world we live in. Turmoil in a country thousands of miles away plasters our social networks, convincing us that our own corner of the world is meant for similar fates, though even ten years ago we would not have heard rumblings of the news for hours, fifty years ago it might have taken days, and before that weeks, years. Information and panic sweeps through us as quickly as keystrokes are entered into a social network.

What if an deadly illness moved that so fast? What if it was as bad as we all feared? What if it was worse?. Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven ponders that question. An illness sweeps through a society wracked by their own fears and doubts. The world that awaits the few survivors, a world without advanced technology, societal borders, and laws, is recognized not for what it promises but for what was lost. “I stood looking over my damaged home and tried to forget the sweetness of life on Earth,” opines Dr. Eleven, a comic book character who dwells on the titular space station, early in novel. Regret lies heavy at the heart of Mandel’s post-apocalyptic tale. But, beside it — a beacon of hope — is nostalgia.

I was thinking about the island. It seems past-tense somehow, like a dream I once had.”

Arthur Leander, Station Eleven, p. 155

But where there is regret, hope also lingers.

In Station Eleven, Mandel is playing in a science fictional sandbox insomuch as she’s envisioning the societies of a post-apocalyptic Earth, but she leaves many of the genre’s toys to other others. Toys over-complicate issues, and so Mandel leaves them behind for only the most basic of tools: sand and water, character and environment.

Station Eleven follows two main narrative threads: Kirsten and the Travelling Symphony in the post-Georgia Flu world, and Arthur Leander during his rise to fame as a preeminent Hollywood actor. Throughout the novel, Mandel lays delicate parallels between Arthur’s journey from the small island of Delano in British Columbia to the lights of Hollywood, and the change forced on humanity by its decimation by the flu.

“I was thinking about the island,” Arthur writes to an old friend. “It seems past-tense somehow, like a dream I once had.”1 Before his slow introduction to Hollywood and New York City — to the terrifying vastness of stardom — Arthur begins life in a small, isolated community where the outside world may as well not exist, before his slow introduction to Hollywood and New York City, to the terrifying vastness of stardom. His whole adult life is spent adjusting to fame and life in the public eye.

I walk down these streets and wander in and out of parks and dance in clubs, and I think ‘once I walked along the beach with my best friend V., once I built forts with my little brother in the forest, once all I saw were trees’ and all those true things sound false, it’s like a fairy tale someone told me.

Station Eleven, p. 155

Then, as though Hollywood Arthur were deposited back on his home island, with no provocation or desire, and asked to adapt to that isolated life, the post-Georgia Flu world is humanity deposited onto a million Delano Islands, scattered groups isolated by the sudden enormity of their empty world. “I stand waiting for lights to change on corners in Toronto,” Arthur finishes in his letter to his friend, “and that whole place, the island I mean, it seems like a different planet.”

Mandel avoids the temptation to play prophet of the apocalypse in Station Eleven. She doesn’t write her novel as a warning against global warming, political radicalism, or alien invasion. She doesn’t scream “The end is nigh!” between the lines of her narrative. Instead, she focuses on the changing of the world, the changing of human culture in the wake of its near destruction. Station Eleven is much more interested in focusing on the small, personal stories of the survivors and their ability to adapt to new surroundings — a new world — than in judging humanity for failing itself.

No more diving into pool of chlorinated water list free from below. No more ball games played out under floodlights. No more porch lights with moths fluttering on summer nights. No more trains running under the surface of cities on the dazzling power of the electric third rail. No more cities. […] No more Internet. No more social media, no more scrolling through the litanies of dreams and nervous hopes and photographs of lunches, cries for help and expressions of contentment and relationship-status updates with heart icons whole or broken, plans to meet up later, pleas, complaints, desires, pictures of babies dressed as bears or peppers for Halloween. No more reading and commenting on the lives of others, and in so doing, feeling slightly less alone in the room. No more avatars.

pp. 30-31

Station Eleven is about the effects and privileges removed from modern society. No longer can we hide behind the avatars that we have constructed for ourselves, instead we’re naked and true. Mandel asks the reader to consider how life might change if they were forced to throw away their ability to hide behind life’s conveniences, to start over in a society that remembers the privilege of the past but must live only in its shadow. In that shadow, some are less lonesome than they were before — some find a home. For others, it is not so easy to let go of the past.

But one cannot simply draw a line in the sand between those caught in the past and those who embrace the future. The past undeniably intrudes upon the present, informs the future. This is something that is true for all of us, from the most nostalgic to the most forward thinking. How we let those events gone by manipulate our personalities and actions is the difference between the past living on and fading away like a dream upon waking. Mandel’s novel explores all of these various relationships between Dickens’ ghosts.

“I dreamt last night I saw an airplane,” Dieter whispered.

[…]

“I haven’t thought of an airplane in so long.”

“That’s because you’re so young.” A slight edge to his voice. “You don’t remember anything.”

“I do remember things. Of course I do. I was eight.”

Dieter had been twenty when the world ended. The main difference between Dieter and Kirsten was that Dieter remembered everything. She listened to him breathe.

“I used to watch for it,” he said. “I used to think about the countries on the other side of the ocean, wonder if any of them had somehow been spared. If I ever saw an airplane, that meant that somewhere planes still took off. For a whole decade after the pandemic, I kept looking at the sky.”

“Was it a good dream?”

“In the dream I was so happy,” he whispered. “I looked up and there it was, the plane had finally come. There was still civilization somewhere. I fell to my knees. I started weeping and laughing, and then I woke up.”

Station Eleven, pp. 133-134

In all ways, those memories are the difference between characters who can move on from the past, see the opportunity in the new world, and those that are passively waiting to wake from their nightmare. By setting her story in a world that’s at once trying to create a new future for itself, while still nostalgic for its stolen past, Mandel creates a speculative playground that has a level of delicacy and nuance often missing from post-apocalyptic narratives.

“If hell is other people, what is a world where almost everyone was gone?” muses Kirsten as she watches a deer cross a road slowly being reclaimed by nature. The empty landscape through which the Symphony travels through is a stark contrast to pre-Georgia Flu Earth, to Aurthur Leander’s cocaine-fueled Hollywood, or Jeevan’s chaotic tumble from one career to another. It is quiet and vast, peaceful, and in slow recovery from the blight of humanity’s spread across its surface. Woven throughout the narrative is an underlying challenge to the common and self-centred perception that the end of the world is synonymous with the end of the human race. “Perhaps soon humanity would simply flicker out,” Kirsten concludes, but she finds such a thought more peaceful than sad.

The world’s become so local, hasn’t it?

Setting a story pre- and post-pandemic might not be a wholly original plot construction, but Mandel wields the trope with a skilled hand, playing the bifurcated story elements off one another and luring the reader into a false sense of comfort before pulling the rug out from under them. To understand the future that Mandel crafts, the reader must also grasp the present as the author conceives it. What she says about a post-Georgia Flu Earth speaks loudly about the present day we live in.

What was lost in the collapse: almost everything, almost everyone, but there is still such beauty. Twilight in the altered world, a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in a parking lot in the mysteriously named town of St. Deborah by the Water, Lake Michigan shining a half mile away. […] And no in a twilight once more lit by candles, the age of electricity come and gone, Titania turns to face her fairy king. “Therefore the moon, the governess of floods, pale in her anger, washes all the air, that rheumatic diseases do abound.”

pp. 57-57

Against type, Station Eleven is not a post-apocalyptic novel about the end of the world, about the horrors of humanity when it returns to its basest of states. It is a novel about the light that pervades through centuries, those parts of humanity that exist because as a race we are able to act outside of our instincts, and make beautiful things in the quiet times between fighting for survival and taming the world around us. The Travelling Symphony moves from community to community bringing music and laughter, reminiscence and wonder to the survivors, to those who need hope most.

That is not to say that there isn’t a certain bleakness to Station Eleven. Through delicate and often poetic prose, Mandel illustrates a world of desperate people shored up in communities guarded by snipers who shoot anything (or anyone) that moves on sight, of cults, and abandoned Walmarts; but the natural world is still healthy — free from mass agriculture and greenhouse gases, deforestation — and the bleakness is not relentless. Instead, there are moments to breathe, suggestions from Mandel that the near end of humanity is not the same as the apocalypse. Some of the novel’s most despairing events occur during its quietest, most intimate moments in the world before the Georgia Flu arrives.

When one can come to grips with the world that Mandel illustrates, then the challenge becomes not accepting that the world has ended — that civilization has collapsed — but that the privileged have been toppled and cast among the unprivileged. There exist today living conditions that mirror any and all the exist in Mandel’s novel, and so we see ourselves in the post-Flu world.

Buy Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel

Station Eleven should be on every bookshelf.

Station Eleven is a tremendous achievement of character and speculation, a gorgeous examination of life before and after a moment in history that challenges humanity to be better, to grow from its most despairing moment into something stronger and more beautiful than before. Mandel poses an impossible question: Is this post-apocalyptic Earth worse off than what came before? To challenge readers in such a way, to take a tired genre and tilt it just to the point that its beauty begins to show through the grime, proves that Mandel is one of our most thoughtful and elegant writers.

The last time a novel created such an intense reaction in me was Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus. It’s quiet and riveting, beautiful in its optimism, and avoids so many of the general cliches of post-apocalyptic fiction, while still subverting its tropes in interesting ways. Gorgeous all around, Station Eleven should be on every bookshelf — creased and worn, dog-eared and well-loved.

The post No More Avatars appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

February 9, 2015

“A Tribute to South African Science Fiction & Fantasy” by Lauren Smith

I seldom felt that this fiction resonated with my experience of South Africa

South African speculative fiction is single-handedly responsible for getting me interested in my own country’s fiction. If you’re from the US or UK you’ve probably never thought of the novels from your country as being largely monolithic or just completely avoided all of them on the assumption that they would be dreary. But that’s exactly how I felt.

Because we were in school after the change in government, many people in my generation seem to have grown up thinking of local fiction as synonymous with the kinds of depressingly tragic political books you were forced to read for class. Books about racism, poverty, apartheid – that’s how I’ve often heard them described. South African books were grim, weighty things. Important and well-crafted maybe, but they offered no pleasure or entertainment. For the few who liked reading (we don’t have a strong reading culture) all the books you could actually enjoy came from somewhere else.

I know it was – and probably always will be – vital for us to have overtly sociopolitical literary fiction, but even as a non-white person growing up in a disadvantaged community, I seldom felt that this fiction resonated with my experience of South Africa or catered to my interests, which – shockingly – aren’t defined by the way apartheid screwed me and my family over. I’ll never be free of apartheid’s legacy, but at the same time I’ll never be so consumed by it that I expect everything we create to carry all the miserable weight of history. I don’t want to put an end to political fiction rooted in stark reality; it’d just be nice to have lots of other stuff too.

So when Lauren Beukes’s debut novel Moxyland came out, I was really happy. Suddenly local fiction could be fun and full of exciting ideas. It could have a thrilling plot that, for once, happened in the same place that I lived. It could still acknowledge or engage with our troubling history and the grotesque inequality it left behind, but it could do that without making me feel like I was chained to the past. And it could even – *gasp * – not be about South Africa at all!

Now I’m gradually collecting all the SA sff that piques my interest – a relatively easy task, as there still isn’t that much of it. Non-fiction tends sell better here, and SA crime fiction seems to be doing well, so I guess publishers have been slow to invest in anything so brazenly ‘unrealistic’ as science fiction, fantasy or horror. Authors who want the freedom to write what they like (and get it published) may be better off approaching international or indie publishers. Nevertheless, the last few years have seen a significant increase in sff publications. The genre is dominated by white authors, but that’s hardly anything new in sff, and hopefully we’ll see more diversity as genre fiction becomes more popular. It’s an exciting time in SA publishing, an opportunity to watch a literary movement blossom.

As a kind of tribute to that, I decided to share some sff novels set in South Africa that have me particularly fired up about local fiction. They’re not necessarily my favourites, and I was very critical of some of them, but they all mean something to me nevertheless. You might not find them in brick-and-mortar stores outside of SA, but they are available on Amazon. And since most of you have probably heardof Lauren Beukes’s work, I thought I’d focus on lesser-known titles.

Apocalypse Now Now by Charlie Human

I just love the title of this novel. “Now now” is a South Africanism that, paradoxically, never means “now” but rather “soon” and quite possibly “later”, especially if you’re a Capetonian (we can be laid back like that). With that title, two spectacular covers by award-winning SA illustrator Joey Hi-fi, and an action-packed plot full of African folklore and mythology, I could never resist this book. It somehow had me rooting for a porn-peddling schoolboy who could possibly be an insane serial killer, but might also be the answer to the apocalypse (which comes later). My favourite scene featured a battle with a “township tick” – a monster that impoverished communities feed sacrifices to because it generates the electricity that keeps their lights on.

Although the excess of ideas and action in Apocalypse Now Now ended up being a bit too much for me, I still think it’s so damn awesome. The sequel Kill Baxter, came out last year and is now sitting at the top of my tbr pile.

Dark Windows by Louis Greenberg

I know I started this post complaining about overtly political literary fiction, but I make an exception when Louis Greenberg is writing it. Greenberg is the “L” in S.L. Grey, pairing up with Sarah Lotz to write The Downside, a horror satire series starting with The Mall. Dark Windows is his solo project, a speculative literaray novel that’s hard to categorise.

It’s set in alternate Johannesburg, with a progressive New Age government run by the Gaia Peace party, which miraculously cured crime and provides reliable social welfare for all. I interpreted this as a commentary on current domestic politics – the idea of us having a good government that actually solves problems is as unlikely as a government based on colour therapy and herbal tea. No surprise then, that this miracle government seems to be losing a battle with the harsh reality of South Africa’s past. Some wish to topple it, perhaps just because they can’t believe it’s not a hoax. Drastic change is coming, but whether it’s social upheaval or some supernatural event prophesied by a mystic, no one really knows.

Deadlands by Lily Herne

There’s nothing new about dystopian YA or postapocalyptic zombie novels, but it was pretty awesome to have one set in Cape Town, written by South African authors (Lily Herne is the pseudonym for Sarah Lotz and her daughter Savannah).

Deadlands is the first in the Mall Rats series, set a decade after a zombie breakout in the midst of the 2010 Soccer Worldcup. The narrator, Lele, is a teenager in a survivor settlement, but later finds herself with a group of teenage rebels who specialise in raiding a nearby mall.

Admittedly, I wasn’t crazy about Deadlands. There were lots of little things about the writing and structure that really bugged me. But on the bright side, it had some great characters and lots of action. All the things I didn’t like were ironed out in the sequel, Death of a Saint, which I absolutely loved. I still have to read the subsequent books – The Army of the Lost and Ash Remains.

Devilskein & Dearlove by Alex Smith

This one was on my best-of list for 2014. Devilskein & Dearlove is a modern retelling of The Secret Garden, set in an apartment block on the famous Long Street in Cape Town. Erin Dearlove uses a snooty, surly persona to mask the unbearable grief of losing her family in a horrific home invasion that she won’t admit happened (she tells people they were eaten by a crocodile in their designer mansion). Feeling somewhat monstrous herself, she tries to befriend Mr Devilskein, the demon living in no. 6616. His otherworldly apartment contains a multitude of realities – souls people have sold to the devil. Each soul is locked behind a door, and Devilskein is the keeper of the keys. He tolerates Erin only because he wants to steal her heart to replace his ailing one.

Besides falling in love with the quirky fantasy of this novel, I really appreciated how seriously it took the decisions of its young main character. She starts the novel as victim of something terrible she could never have controlled, but from then on her decisions have significant consequences, both for her and those close to her, whether she chooses wisely or makes terrible, terrible mistakes. It’s a lovely, whimsical novel, but doesn’t shy away from darker content, which is something I appreciate in YA.

Sister Sister by Rachel Zadok

I just finished this one, and I’m trying to wrap my head around it. The beautiful cover belies an unexpectedly dark story set in a future Johannesburg ravaged by climate change. It’s not postapocalyptic, although it often seems that way because it’s written from the POVs of a pair of homeless twins; the danger and suffering they face on the streets makes it seem like some unfamiliar, primitive world. However, it’s clear that more privileged lives are carrying on without them, as Thuli and Sindi watch electric cars driving down the highway at rush hour, or peer through the bars of locked gates around the safe homes they will never live in. It’s the kind of inequality that you’ll find depicted in any SA novel that seeks to offer a realistic portrayal of our society, whether it’s sff or not.

In Sister Sister, the imagery of sun-baked roads, lost souls and discarded things sets the stage for a tale that alternates between feeling fantastical and disturbingly real. The book deals with issues of belief, child abuse and HIV/AIDS – not something I’d normally jump to read, but Zadok handles it with creativity and grace.

I hope this list gives you a starting point, and if you like you can find reviews of them on my blog (except for Sister Sister, which is in progress). But it’s just a start. I considered adding Mary Watson’s The Cutting Room to this list and chose not to only because it’s not explicitly sff. There are other authors, not all of whom write about South Africa, who’d no doubt be on this list if I had more time to read – Cat Hellisen, Henrietta Rose-Innes, Andrew Salomon, Diane Awerbuck, Nerine Dorman, Dave-Brendon de Burgh, Liz de Jager, Melissa Delport… In the meantime I’ll try and do my bit to keep the list growing.

The post “A Tribute to South African Science Fiction & Fantasy” by Lauren Smith appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

February 6, 2015

Dragonmount founder Jason Denzel sells fantasy trilogy to Tor Books

Tor.com announced today the upcoming release of the Mystic trilogy by Jason Denzel, longtime Robert Jordan fan and found of Wheel of Time megasite Dragonmount. On first glance, Denzel’s trilogy appears to be in the classic ’80s mould of epic fantasy that will be sure to appeal to fans of Jordan, Katharine Kerr, and Terry Brooks, or more contemporary authors like Brent Weeks and Kate Elliott.

Here’s the early rundown:

The Mystic trilogy will tell the story of Pomella, a restless teenager who leaves her village to apprentice herself to a mysterious Mystic – even though the law forbids it. After lying about her caste, she must undergo severe trials against nobles to prove her worthiness. Far more dangerous, however, is the conspiracy she finds: someone is plotting to murder her and the Mystic!

As founder of Dragonmount, the largest Wheel of Time fansite on the Internet, Denzel has had a long professional relationship with Tor Books via Robert Jordan’s long-running series.

“Having the opportunity to publish my stories through Tor is a dream come true,” Denzel told Tor.com. “For over a decade I’ve had the pleasure of frequently collaborating with their team to celebrate Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series. Now, thanks to the trust they’ve shown me, I get to tell my stories in my own style and voice. I look forward to sharing the Mystic trilogy with everyone, and getting the chance to connect with new fans.”

The first volume of the trilogy, Mystic, will be released on November 3rd, 2015. It followed by the remaining volumes, Mystic Dragon and Mystic Skies, at a later date. The cover art for the trilogy will be illustrated by Larry Rostant.

The post Dragonmount founder Jason Denzel sells fantasy trilogy to Tor Books appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

February 5, 2015

Tad Williams completes The Witchwood Crown

Art by Kerem Beyit

OstenArd.com, reporting on an announcement by Tad Williams’ wife and business partner, Deborah Beale, revealed that Williams has completed work on the first draft of The Witchwood Crown. This novel is the first volume of The Last King of Osten Ard trilogy, a follow-up to Williams’ genre-defying epic fantasy trilogy Memory, Sorrow and Thorn. Aside from one short story, “The Burning Man”, this is the first time that Williams has returned to the world of Osten Ard since publishing the final volume of Memory, Sorrow and Thorn in 1993.

“The Witchwood Crown is expected to be published in Spring 2016,” OstenArd.com said. “[It] will be followed by Empire of Grass and The Navigator’s Children.” Williams has previously announced that legendary artist Michael Whelan, who painted the covers for Memory, Sorrow and Thorn, will be responsible for the cover art for the North American edition of the trilogy from DAW Books.

The post Tad Williams completes The Witchwood Crown appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

February 4, 2015

50,000 Shades of Grey

On the surface, The Mirror Empire, the first volume in Hurley’s The World Breaker Saga, is an epic fantasy about two warring empires. Not a wholly original concept, but Hurley’s take on the familiar story is a relentless avalanche of a novel that crams so many original ideas — clever magic, the intertwining politics of the warring empires, cultures with non-binary genders — that the familiarity of the overall plot is a beacon for readers to orient themselves while navigating Hurley’s twisted imagination. Her willingness to overtly and wholly subvert conventional genre tropes, specifically the Hero’s Journey1, is a testament to both Hurley’s understanding of the genre and her willingness to tear the house down around her just so she can build it up again. The Mirror Empire works both as a traditional secondary world fantasy, and as a complete dissection of the genre — few authors have the chops to pull off such a bold narrative.

“Sometimes prophets of the cataclysm get lucky.”Nasaka Lokana Saiz, The Mirror Empire, p. 169

Hurley often jokes that she receives mail from her readers about their frustration with not being able to nail down the villain of her story – or the hero. The Mirror Empire follows four main characters — Lilia, Zezili, Roh, and Akhio.Their labyrinthine paths through the novel blur the line between the concept of heroes and villains, a common trope in secondary world fantasies. Hurley sets up Lilia in the mold of a traditional hero — orphaned scullery-girl with a hidden past — and yet she does some despicable things when faced by a desperate and dangerous world. In parallel, Captain General Zezili, responsible for carrying out the genocide of thousands of Dhai, makes some choices that the reader must begrudgingly respect, or even admire.

Hurley’s mirrored empires are not black and white, light and dark, wet and dry. They are grey, and dim, and muddy.

The Mirror Empire isn’t always an easy novel to read. Violence pervades theworld at almost every turn, and Hurley never checks her punches. Where many novels give their characters (and the reader) a break between traumatic scenarios, and opportunity to breathe, Hurley throws haymaker after haymaker. A jab from the left is the only relief she offers. Hurley creates such a state of misery for all of her characters, especially those that are more passive in their engagement with the world, that they’d be happy to jump ship into a Robin Hobb novel just for a break.

Much has been said of ‘grimdark’ as a sub-genre of secondary world fantasy, and The Mirror Empire will greatly appeal to fans of Mark Lawrence or Joe Abercrombie. Where Hurley’s writing excels is in her ability to create dramatic and horrifying situations that not only trouble the reader, but also provide context for the world and events unfolding before their eyes. The bloody evisceration of Hurley’s delicate worldbuiling is like a punch in the gut because she turns expectations on their head at every turn. There are so many admirable aspects to her cultures and her characters that the pain from their betrayal hurts even more. Even while working within the generally accepted bounds of ‘grimdark,’ Hurley still finds room to poke fun at the concept:

“Why don’t you want us here?” Roh said. “We’re fighting the same enemy. We should be friends.”

Wraisau grinned and glanced over at Driaa. “You must admit,” he said, “he grows on you.”

“It’s dumb talk,” Driaa said.

“It’s the way we all sounded before the war,” Wraisau said.

“I never sounded like an illiterate Dhai,” Driaa said.

“I can read,” Roh said.

“Ze means you lack wisdom,” Wraisau said, using the Saiduan pronoun for ataisa2 to refer to Driaa. “But to be honest, I could do with some company who has a little more hope than sense these days.”

The Mirror Empire, p. 221

Hurley forces readers to examine situations and tropes that are accepted as genre conventions – tropes, cliches – by flipping gender conventions around (dismissing them entirely by adding new genders to her societies; writing a character who changes gender throughout the novel) and putting male characters into situations usually held for women, and vice versa. With the rape and objectification of women so prevalent in this ‘grimdark’ fantasy market, Hurley’s clever and calculating treatment of Anavha will make even the staunchest of red-blooded readers quiver. And we have to ask ourselves why a scene where a man is almost raped by several female soldier’s is so unsettling, while flipping those genders around feels passe. What does that say about the sub-genre’s tendencies towards rape? Hurley takes the idea of rape and objectification as a casual and easy plot device and jams it all the way down the readers’ throat until it curls around their toes.

Monstrousness is contextual.

“Monstrousness is contextual,” Foz Meadows said3, and Hurley masterfully wields context to give new meaning to old tropes and and tired cliches. Hurley earns her violence by spreading it through cultures where it is either a) culturally relevant and ingrained in a slave-based colonialistic empire, or b) abhorrent to their pacifistic values. In a culture where steadying someone when they trip can be interpreted as socially unacceptable, physical violence takes on a new meaning. How can these two cultures reconcile their differences? How can they fight a war?

Where Hurley’s handling of complex themes – such as the fluidity of gender or the impact of a consent-based culture – and characterization is delicate, a lot of the plot development The Mirror Empire, especially during the beginning and end of the novel, is heavy-handed and oftentimes confusing. Convincing a reader of two parallel worlds occupied by the same characters and societies, yet entirely different socioeconomic and natural environments, is a heady task. Chaos theory need not apply in Rasia, apparently. Hurley alternates between mind-bending revelations, sickeningly clever plot twists, and a muddy and labyrinthine explanation of how the two worlds interact, but it’s hard to shake the feeling that it’s all a bit overcomplicated. Still, in a genre that asks you to believe in so many unbelievable things, Hurley’s concept of a world at war with its mirror self goes down easier if the reader faithfully agrees with the narrative that it all works, to stop asking questions.

Part of this issue stems from there being too many point-of-view characters in the novel. Multi-PoV novels are certainly not uncommon in secondary world fantasies, but Hurley’s novel works best, and is at its least confusing, when the narrative focuses on the novel’s four core protagonists, and becomes jumbled by the introductionof several secondary characters, some who only appear on screen briefly. Considering the density of the world, and the confusing interaction between the two mirrored worlds (two groups of people called Dhai?), the multi-PoV structure places extra burden on the reader to remember what’s going on, where it’s taking place, how everybody’s personal and political aspirations align, and to understand the metaphysical relationship between the mirror empires.

Buy The Mirror Empire by Kameron Hurley: Book/eBook

The Mirror Empire is an audacious and exciting start to an epic fantasy that is sure to leave a mark on the world.

Despite this complexity, and the oft-prevelant feeling of being lost, Hurley writes with such hard hitting passion, undeniable skill, verve and tenacity, that I couldn’t help but fall deeply into the novel. The Mirror Empire‘s outer narrative, the one summarized on the back cover, is about a bloody war between two empires – it’s about assassins and magic, ascending satellites and a suicidal Kai – but the narrative at the core of the novel, its beating heart, is that of desperate characters trying to survive in a world that is falling apart around them, about finding solace in people you don’t understand, and fighting against all odds.

I don’t become obsessed with books very often these days. I was obsessed with The Mirror Empire by the time I was fifteen pages in until I turned the last page. I was obsessed with it for days afterwards. I’m still obsessed with it. Hurley took science fiction and fantasy by storm in 2014 with her fan writing, her scaly llamas, but The Mirror Empire is proof that her star is just beginning its ascent. The Mirror Empire is an audacious and exciting start to an epic fantasy that is sure to leave a mark on the world.

The post 50,000 Shades of Grey appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.

February 2, 2015

“The Indispensable Prostitute” by Elizabeth Bear

“Gosh, Bear,” you might think, “at least she’s a good person, in spite of being a prostitute!”

Hi! I’m Elizabeth Bear, the author of Karen Memory, and I’m here to talk about the fine art of avoiding some of Western literature’s most tired sex-worker tropes, such as The Disposable Prostitute and The Hooker with a Heart Of Gold.

On The Hooker with a Heart of Gold… words to strike dread into the hearts of… well, everybody who ever consciously tried, in their work, to avoid a stereotype. Any stereotype. And it’s not the only—or worst—stereotype—of sex workers around!

“Gosh, Bear,” you might think, “at least she’s a good person, in spite of being a prostitute!”

In fact, it’s hard to think of a fictional prostitute who isn’t a stereotype of some sort or another. Who isn’t in some respect othered, exoticised, and placed in an object position. It’s what we do, as a society. Sex workers aren’t people. They’re whores. This societal attitude is brutal, and prevalent, and it’s often fatal. It’s the reason many serial killers prey on prostitutes. Because they can get away with it. Because very few people care. These women are, quite simply, seen as disposable.

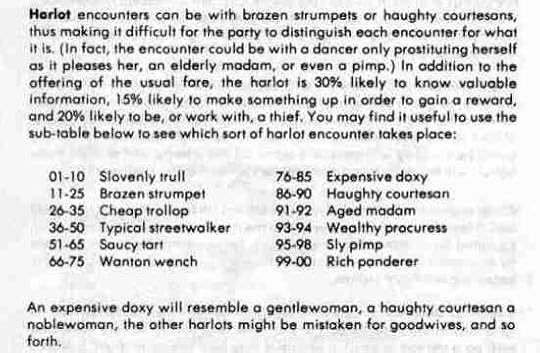

I made a joking comment many years ago about Frank Miller Feminism: all the women are whores, but some are really badass whores. It applies. Every nerd in the room over the age of 35 surely remembers the old D&D Prostitute Encounter table, after all! (see above.) If that isn’t a list of common stereotypes, I’ve never seen one.

The thing is—like soldiers, police, firefighters, nurses, clerks, lawyers, rock stars, T.S.A. agents, and society ladies—like every other role by which people are generally filed, sorted, and categorized as being nothing but their profession, without any regard for who they are in the privacy of their own heads—sex workers are people. Characters who are sex workers are characters first, and sex workers second. It’s a job.

So I asked myself, when I undertook to write a book about parlor girls in a steampunk version of the Gold Rush West, who these women really were. What they did with themselves when they weren’t punching a clock.

I have a little postcard print of a fairly famous period photo that hangs in the preserved portions of the Seattle Underground, which can be toured. It shows a group of parlor girls awaiting their clientele in a room decorated with statuary and Asian carpets, and the striking thing about them, for me, is their individuality. The variety of expression on their faces. Their body language, and the varying ways in which they address the camera. (One of these ladies was the inspiration for Miss Francina, by the way.)

One of the great joys in having a number of female characters […] is that it neatly dodges the Smurfette Problem.

So I felt, in writing this book, that I owed these hard-working, adventuresome, mettlesome women a little respect. I tried to make them an assortment of very different people, with different goals and experiences and desires. Also, one of the great joys in having a number of female characters in a story—in telling a story in a predominately female homosocial environment—is that it neatly dodges the Smurfette Problem. Which is to say, one woman is not presented as the type example of all women, as—to steal a title from John D. MacDonald— “The Only Girl in the Game.” We avoid female exceptionalism by avoiding female exceptionalism. Bang!

(Also, there are a lot of stories set in primarily male environments. I’ve written a few myself. It’s fun to address a women’s domain through the eyes of the women who live and work there, for a change.)

Buy Karen Memory by Elizabeth Bear: Book/eBook

And the thing is, for Karen and her colleagues, prostitution is a job. It’s how they make a living, not how they identify themselves. The protagonists of most urban fantasy novels seem to work waiting tables or as private investigators, if they’re not starving artists. Either their job is the adventure, or it’s something that provides a gateway to the adventure, but we’re never supposed to care too much about the job qua job itself!

So Karen’s job gives her an entre into her adventure—but it certainly doesn’t define her. And to me, the adventure is the interesting thing. She’s not having adventures or being a good person in spite of being a prostitute. She’s a prostitute, and she also gets to have adventures.

As to whether she’s a good person, well, I’ll leave that to the reader to judge. I sure like her, anyway.

The post “The Indispensable Prostitute” by Elizabeth Bear appeared first on A Dribble of Ink.