Matt Rees's Blog, page 9

August 31, 2012

Bob Dylan Self-Help Guru: Jon Friedman's Writing Life interview

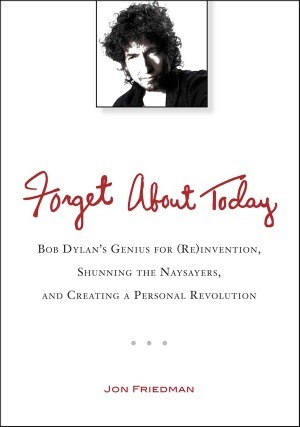

Jon Friedman's first book was what you might expect from a young financial-markets journalist. Published in 1993, "House of Cards" was a fast-paced story of the blunders at American Express during the 1980s, including smear campaigns, duff accounting, and a CEO whose name was synonymous with hubris (until, in recent years, hubris became the official middle name of everyone on Wall Street.) Now as media columnist for The Wall Street Journal's MarketWatch, Friedman's latest book is rather more off-beat than his debut. In Forget About Today: Bob Dylan's Genius for (Re)invention, Shunning the Naysayers, and Creating a Personal Revolution

Jon Friedman's first book was what you might expect from a young financial-markets journalist. Published in 1993, "House of Cards" was a fast-paced story of the blunders at American Express during the 1980s, including smear campaigns, duff accounting, and a CEO whose name was synonymous with hubris (until, in recent years, hubris became the official middle name of everyone on Wall Street.) Now as media columnist for The Wall Street Journal's MarketWatch, Friedman's latest book is rather more off-beat than his debut. In Forget About Today: Bob Dylan's Genius for (Re)invention, Shunning the Naysayers, and Creating a Personal RevolutionHow did you get the idea for the book?

I got the idea for the book from reading the “Oh Mercy” chapter of Dylan’s 2004 memoir. Dylan wrote in detail about his strategy for rebuilding his career, which was in tough shape in the 1980s. I recognized then that this was a musician of rare intellect who could solve his problems in a business-like way. Then, I realized that Dylan had a lot to offer people, in a classic “self-help” model.

What sort of influence has Dylan had on the way you live YOUR life?

“To live outside the law you must be honest,” as Dylan sang in “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” Be honorable in your dealings and true to yourself.

Who ought to read this book?

This book can benefit everyone, from baby-boomers who idolize Dylan for his music and influence to young people who want to learn from a success story who has lasted for FIFTY years and is still going strong.

You're suggesting Dylan can offer lessons for how to live your life, or perhaps how to handle your professional life? But surely he made a lot of mistakes too. How do you account for them?

Dylan is a constant innovator. At times, he has been ahead of his time (such as when he “went electric”). But he also can be stubborn, such as when he initially resisted the advent of MTV. He is human. When he went on stage at Live Aid with Ron Wood and Keith Richards, that was a huge mistake (because they weren’t prepared) and he squandered a big opportunity. Nobody is perfect.

About the writing in particular: how did you set about it? Did you structure the book in a detailed way? Did you know exactly what you'd write before you did it?

I came up with the general theme and drew up an outline. Once I determined the chapter titles, the structure came into play. As any book-writer of fiction or nonfiction can attest, having the structure is really, really important. I had no shortage of anecdotes drawn from Dylan’s life to underscore my points in each chapter. Actually, I left a few interesting ideas on the cutting room floor in my attempt to go for brevity here.

How did it compare to the writing of "House of Cards"?

My first book was an expose of a once-troubled corporate icon (American Express) in the late 1980s. My book on Dylan is more of a celebration of his success, longevity and comebacks.

Are there other stars whose careers we could use as models for our own and will you be writing another book about one of them?

Ah, the big question! Yes, and I hope so. You could examine the career of any “superstar” in music, art, culture, politics, religion and sports to make these points. I have someone in mind, yes, but it is premature to discuss the subject.

July 25, 2012

My Radio Wales interview on Caravaggio, Mozart, historical fiction and crime fiction

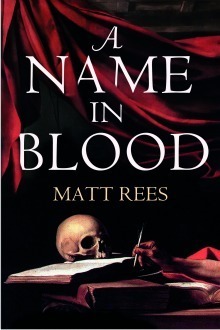

I stopped in at Radio Wales to meet the delightful Roy Noble, who has had a show every afternoon for a couple of decades. We chatted about my new Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, as well as MOZART'S LAST ARIA and my Palestinian crime series. It's a wide-ranging, easy-going discussion, which is how the best interviewers always do it. Thanks, Roy!

I stopped in at Radio Wales to meet the delightful Roy Noble, who has had a show every afternoon for a couple of decades. We chatted about my new Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, as well as MOZART'S LAST ARIA and my Palestinian crime series. It's a wide-ranging, easy-going discussion, which is how the best interviewers always do it. Thanks, Roy!

Published on July 25, 2012 00:35

•

Tags:

art-history, author-interviews, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, mozart, music, radio-interviews

July 20, 2012

Lost News of the World Exclusive: Caravaggio Cellphone Hacked!

The great Italian painter Caravaggio was threatened with death by the Knights of Malta and by the family of a man he had slain in a duel and was in love with one of his models, according to a scoop in The News of the World which was never published because of the demise of the London tabloid.

The great Italian painter Caravaggio was threatened with death by the Knights of Malta and by the family of a man he had slain in a duel and was in love with one of his models, according to a scoop in The News of the World which was never published because of the demise of the London tabloid.The News of the World, which was closed by owner Rupert Murdoch because of a phone-hacking scandal, appears to have gathered its information for the Caravaggio scoop by hacking into the early-Baroque painter’s voicemail.

“Caravaggio, you’re a dead man,” said one unidentified caller from a number with a Maltese country code. “We’re coming to get you.”

Another caller, whose number had a Roman area code, claimed responsibility for an attack which left Caravaggio scarred and said it was in revenge for killing Ranuccio Tomassoni in a duel in 1605. The scar was intended to mark him with shame. “But now we’ve decided to get rid of you for good,” the voice mail says.

Voice messages from a girl named Lena, the model for some of Caravaggio’s most well-known Madonnas, are described as “steamy” and “saucy” by The News of the World article.

Matt Rees, whose novel about the mysterious death of Caravaggio “A Name in Blood” was published this month in the UK, says the voice mails show that Caravaggio was ahead of his time as a painter and as a user of technology. “I’m convinced by the evidence, for example, that he used a camera obscura to obtain his characteristic light-dark effect, because he was aware of the latest scientific discoveries,” says Rees.

“I’m sure the cellphone he had in those days, however, must’ve been one of the big old ones with the separate battery pack. It’d look a lot less modern today than one of the paintings Caravaggio made four hundred years ago and which have had such an effect on the way we look at images today.”

The voice mails don’t resolve the debate over how Caravaggio died, Rees points out. “Art historians often say he died of nothing more than a fever, and the voice mails leave us wondering if it was the Knights of Malta, the Tomassoni relatives, or perhaps someone else,” Rees says. “To really understand what happened, you’d have to read ‘A Name in Blood.’”

Published on July 20, 2012 10:23

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, historical-mystery, italy, malta

July 18, 2012

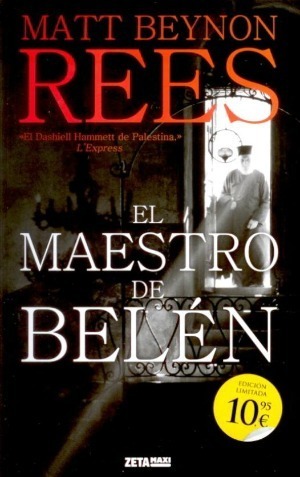

Por la playa: Free foreign language summer book giveaway

I'm giving away copies of my novels in a number of languages. A little summer reading for la playa, or le plage, or i strönd (yes, I have books for you in Icelandic, too). To enter, you need to do two things. First, go to my website and sign up for my newsletter (it's on the right-hand side of the page--and I don't send things out often enough for it to be annoying). Then send an email to mattreesbooks@gmail.com to let me know you've signed up, and also to tell me what language you'd like your book to be in, where I ought to send it, and to whom I should dedicate it (I'll sign the book, of course!) You can chose from books in these languages: Spanish, French, Portuguese, German, Icelandic, Turkish, Korean, Polish, Romanian, Greek, Czech, and Norwegian. By the way, I'll soon be running an English-language book giveaway, so you can send me an email entering for that too, if you sign up for my newsletter. The giveaway runs until August 7, when my four-year-old son will be drawing the names!

I'm giving away copies of my novels in a number of languages. A little summer reading for la playa, or le plage, or i strönd (yes, I have books for you in Icelandic, too). To enter, you need to do two things. First, go to my website and sign up for my newsletter (it's on the right-hand side of the page--and I don't send things out often enough for it to be annoying). Then send an email to mattreesbooks@gmail.com to let me know you've signed up, and also to tell me what language you'd like your book to be in, where I ought to send it, and to whom I should dedicate it (I'll sign the book, of course!) You can chose from books in these languages: Spanish, French, Portuguese, German, Icelandic, Turkish, Korean, Polish, Romanian, Greek, Czech, and Norwegian. By the way, I'll soon be running an English-language book giveaway, so you can send me an email entering for that too, if you sign up for my newsletter. The giveaway runs until August 7, when my four-year-old son will be drawing the names!

Published on July 18, 2012 05:57

•

Tags:

book-giveaway, crime-fiction, foreign-languages, free-books, historical-fiction, promotion

July 2, 2012

Behind the Book: Writing My Caravaggio Novel A NAME IN BLOOD

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let me go.

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let me go.I was in Madrid on a book tour for the Spanish translation of the first of my Palestinian crime novels. The Thyssen is just across the wide, busy Paseo del Prado from the immense museum of that name. It’s a building with two wings: a traditional classical palace in burnt sienna and pink stone; alongside a block of bright white louvered walls and angled blue-glass rooflights, like an old auto factory transported to a sci-fi future. I had no idea what awaited me inside. It was a novel.

The Caravaggio works I had previously seen in London and New York had impressed me. I was aware of the conventional summary of the stylistic revolution he wrought: to fill his canvasses with darkness and, with a strategically placed lantern, to bring the central action shining out of the shadows. That technique has been a major influence on filmmakers like Scorsese and almost every professional photographer, which is why Caravaggio’s four-hundred-year-old paintings look so modern. I knew something about his life too, though largely through the weird distortions and art-house tedium of Derek Jarman, having seen the British director’s Caravaggio film in college. As a writer, however, I’ve found a confluence of impressionability and idea lies behind every novel, so that only at one given time can you write a particular novel. A few years previously, I might’ve seen Saint Catherine, considered her for a moment, then moved on, as I had done when I saw Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus in London’s National Gallery. But, for some reason, when I entered her room at the Thyssen and she spoke to me, I was listening.

I stayed in that room a long time. I couldn’t say quite how long. But it was at least an hour. The other paintings held my attention a matter of moments. I can’t remember them. (I’ve had similar experiences when I’ve traveled to see Caravaggio’s art around the world since then. No artist has such a capacity to make everything else in a gallery ignorable as Caravaggio has). In the Thyssen, I recall that the walls were of a beige rough fabric, a little like delicate sackcloth. The ceiling was white. Details as scant as you might retain from love-making. You might forget your mood or the immediate surroundings, but you’d have a clear picture of the way she looked at you or the feel of her hand on the back of your neck. Of Catherine, I remember everything. Even things that weren’t on the canvas.

The eyes of Caravaggio’s saint were possessive, grasping and sensual, clandestine and forbidden. For much of the time I was with her, we were alone. It felt as intimate as the languor after an act of love. There’s a question in that post-coital moment and Catherine asked it of me: Is this the last time? Will I see you again? Do you want to know more about me and where I come from?

Eventually I tried to leave the empty room. In her face I saw a plea. As if she wanted me to know that by leaving I would abandon her to her fate, represented by the spiked wheel on which she leaned (where the saint was tortured, before she was dispatched with the sword whose shaft she fondles.) What’s so compelling (and in his day was controversial) about Caravaggio is that he didn’t expect the saint’s suffering to be enough to keep you on her side. He gave her the sexual magnetism of Fillide Melandroni, the whore he used as his model.

The hold Caravaggio subsequently took on me amounted to what many people would call an obsession. I prefer not to use that term, because it implies a degree of madness and the inability to see when you’re mistaken about something. A writer needs to know when he’s gone wrong. Still, I traveled all over Europe and America to see Caravaggio’s works. I learned to paint with oils, to fight with a rapier. I grew a beard like the one Caravaggio sported just before his death at age 39. I did a few others things that paralleled the artist’s life and which were too intimate, shameful, or mystical to be recounted here. So, go ahead, call it an obsession.

After Madrid, my long road of research began with Peter Robb’s fabulous biography “M: The Man Who Became Caravaggio.” An Australian who lived a long time in southern Italy, Robb’s account of Caravaggio’s life is detailed in a non-academic way and deeply felt. He examines the mystery surrounding Caravaggio’s disappearance without prejudice, which earned Robb quite a deal of criticism from Caravaggio “scholars” when he published his book in 1998. The “accepted” version of Caravaggio’s demise is a tall tale of mistaken identity, a mad scamper along a malarial coastline, fever, death in a Tuscan convent and an unmarked grave. Academics tend to assume that considering anything other than this hashed-over version of Caravaggio’s death represents a foray into sensationalism, rather than simple curiosity about how this most dynamic of Italian artists simply vanished. (I had encountered a similar preference for the boring and quotidian in professors writing about Mozart’s death, while I researched the composer’s mysterious end for my novel Mozart’s Last Aria. Somehow academics seem committed to taking history’s dramatic events and making them appear as banal as another day in the faculty canteen, and they get inordinately angry with someone like me who decides to eat lunch off campus.)

It’s a considerable undertaking to write a novel about an artist whose works are dispersed around the world, whose pictorial skills you don’t share, and whose life was lived in such a distant time. But I didn’t think for a moment that I shouldn’t write the book. Well, okay, so it really was an obsession…

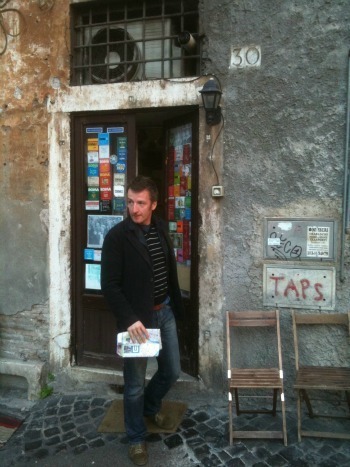

I traveled throughout Italy to see the places that touched Caravaggio’s life. In particular I spent a lot of time in the historic center of Rome, the neighborhoods around the Piazza Navona which are now the tourist heart of the ancient city. In Caravaggio’s day, this was the “Evil Garden,” where the Pope decreed the whores should live. Naturally, where there were whores, there were artists and trouble. In Rome, once more I found a communion with a Caravaggio painting. This time it was perhaps deeper even than the one I shared with Catherine. At the Galleria Borghese, I sneaked around the guards who usher on lingerers so newcomers may pile through the galleries built by Caravaggio’s patron Cardinal Scipione Borghese. I needed more time with the Madonna with the Serpent. This Madonna is based on a girl named Lena, who I made a major character in my novel. I wouldn’t even quibble to say I obsessed about her. I fell in love, and it was clear to me that Caravaggio couldn’t have painted her the way he did unless he had shared that emotion. Here is where some of the mystical aspects of my research come in. I won’t go into detail about them. I’ll only say that I feel as though I’ve met this girl Lena. Certainly, when I learned to paint with oils so as to be able to describe how Caravaggio worked, I painted Lena over and over.

From Rome, I went on to Naples, where Caravaggio took refuge. In the chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, I stood before the great painting now known as Seven Works of Mercy, which is topped by another Lena Madonna (Caravaggio called it Our Lady of Mercy.) The noise and chaos of Naples’s narrow streets spilled through the door of the chapel, just as they had in Caravaggio’s day. I wondered at the force of personality and the drive to create that enabled him to paint this phenomenal work of devotion and love, while separated by a single door from a raucous crowd in which may have lurked the men who wanted to kill him (By the time he went to Naples, Caravaggio had a price on his head for a fatal duel.)

Dueling was another element of my research. I had to know how it felt to wield both a brush and a rapier. By coincidence (in my obsessive state, I sometimes thought it was fated), the Academy for Historical Fencing happens to be located in the town where I was born and where my parents live: Newport, South Wales, a former steel town with little apparent connection to historic chivalry. Nick Thomas, a Medieval and Renaissance sword enthusiast, started the Academy there and so I found myself driving up to Caerleon, the Newport suburb where the Romans once had a fortress, on a Friday night with my Dad, ready to do battle. Within moments of strapping on my chest protector and pushing down a visor tight over my big Celtic head, I found myself amazed at the balls it must have taken to duel with these five-feet-long swords without protective gear. The tip of my opponent’s blade mesmerized me. To fight, I’d have to ignore this point that—in Caravaggio’s circumstances—would’ve killed me in one thrust. It took some doing, I can tell you.

I journeyed on to Malta, where Caravaggio fled and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. I spent December there in a cheap hotel in a four-hundred-year-old building that was without heating and insulation, in a room where one of the windows didn’t close. I got sick. I took some drugs, staring across the harbor at the sheets of rain plummeting down on the Castel Sant’Angelo, where Caravaggio was imprisoned for a time. It got damper in my room. I took too many drugs. I hallucinated, slept at unaccustomed hours and was awake when everyone else was in bed. I saw things that weren’t there. In this condition, I stood all day before The Beheading of Saint John, Caravaggio’s largest canvas and one of his most gruesome and disturbing. It’s the painting where he signed his name—the only time he ever signed a work. And he did it in a deep red, mingling with the blood spurting from the dying saint’s neck, giving me the title of my novel. At night I wandered the narrow, deserted, windswept streets of Valletta’s Baroque center, weaving light-headed over the flagstones under the sad Christmas lights that rocked on the wind. In the alleys, I imagined Caravaggio here, knowing that men sought to kill him. I panted in fear and slugged down some more drugs from the pocket of my raincoat and felt his horror of the dark. I knew why he had painted his figures emerging from the threatening shadows into a light so luminous that it glows straight through your skin and eyes and into the seat of your capacity for love, wherever that may be. I had an answer too, to the questions Catherine posed when she and I parted in Madrid.

Stumbling down the steps toward my hotel above the gate where the Knights used to display the heads of Muslim pirates on spikes, I knew I was ready to write.

Published on July 02, 2012 01:00

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, knights-of-malta, madrid, malta, research, writing

July 1, 2012

Podcast: Touching Caravaggio, Researching 'A Name in Blood'

My latest podcast describes the challenges of researching and writing about the great Italian artist Caravaggio for my novel A NAME IN BLOOD. I deliberately took my research too far, not only learning to fence with a rapier and to paint with oils, but dying my beard and cutting my hair in Caravaggio’s style and using New Age spiritual techniques to connect with the energy of Caravaggio. I did all this because I wanted to be sure I could accurately portray the real Caravaggio, not the “gay psycho bitch” as whom he’s usually portrayed. Here’s how I found the real Caravaggio.

Published on July 01, 2012 01:25

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, italy, podcast, research

June 28, 2012

FREE Book Giveaway A NAME IN BLOOD: Win my new Caravaggio novel

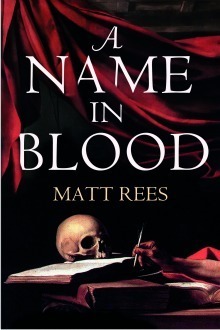

My new novel A NAME IN BLOOD is out in the UK this weekend. To introduce it, I'm giving away five copies of the hardcover edition to the winners of this competition. Ten lucky runners up will get a paperback copy of my last novel MOZART'S LAST ARIA. To enter, go to any page on my website and sign up for my newsletter (in the right-hand column, where it says "Newsletter," enter your email address.) A NAME IN BLOOD is my version of the story of Caravaggio, the great Italian artist. It begins in Italy, 1605. For the ruling Borghese family, Rome is a place of grand palazzos and frescoed cathedrals. For Caravaggio, it is a place of rough bars, knife fights, and grubby whores. Until he is commissioned to paint the Pope…Soon, Caravaggio has gained entry into the Borghese family’s inner circle and become the most celebrated artist in Rome. But when he falls for Lena, a low-born fruit-seller, and paints her into his Madonna series as a simple peasant woman, Italian society is outraged. Discredited as an artist, but unwilling to retract his vision of the woman he loves, Caravaggio is forced into a duel – and murders a well-connected street tough. His powerful patrons can't protect him from a death sentence. So Caravaggio flees to Malta, where he must undergo the rigorous training of the Knights of Malta. His paintings continue to speak of his love for Lena. But before he can return to her, as a Knight and a nobleman, Caravaggio, the most famous artist in Italy, simply disappears… Get the UK edition. Read a sample chapter. Listen to me read a sample chapter.

My new novel A NAME IN BLOOD is out in the UK this weekend. To introduce it, I'm giving away five copies of the hardcover edition to the winners of this competition. Ten lucky runners up will get a paperback copy of my last novel MOZART'S LAST ARIA. To enter, go to any page on my website and sign up for my newsletter (in the right-hand column, where it says "Newsletter," enter your email address.) A NAME IN BLOOD is my version of the story of Caravaggio, the great Italian artist. It begins in Italy, 1605. For the ruling Borghese family, Rome is a place of grand palazzos and frescoed cathedrals. For Caravaggio, it is a place of rough bars, knife fights, and grubby whores. Until he is commissioned to paint the Pope…Soon, Caravaggio has gained entry into the Borghese family’s inner circle and become the most celebrated artist in Rome. But when he falls for Lena, a low-born fruit-seller, and paints her into his Madonna series as a simple peasant woman, Italian society is outraged. Discredited as an artist, but unwilling to retract his vision of the woman he loves, Caravaggio is forced into a duel – and murders a well-connected street tough. His powerful patrons can't protect him from a death sentence. So Caravaggio flees to Malta, where he must undergo the rigorous training of the Knights of Malta. His paintings continue to speak of his love for Lena. But before he can return to her, as a Knight and a nobleman, Caravaggio, the most famous artist in Italy, simply disappears… Get the UK edition. Read a sample chapter. Listen to me read a sample chapter.

Published on June 28, 2012 23:28

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, book-giveaway, caravaggio, competition, crime-fiction, free-book, historical-fiction

Taking My Research TOO Far: Caravaggio and Willy Wonka

As Willy Wonka says in “Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator,” the wisest men know that they need to indulge in some nonsense from time to time. Which is why I like to take my research for my novels just a bit too far.

As Willy Wonka says in “Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator,” the wisest men know that they need to indulge in some nonsense from time to time. Which is why I like to take my research for my novels just a bit too far.For A Name in Blood I did more than just read about the great Italian artist Caravaggio and look at his work. I learned to fence with a sixteenth-century rapier and to paint with oils, for example. A bit beyond the call of duty, but so far so reasonable.

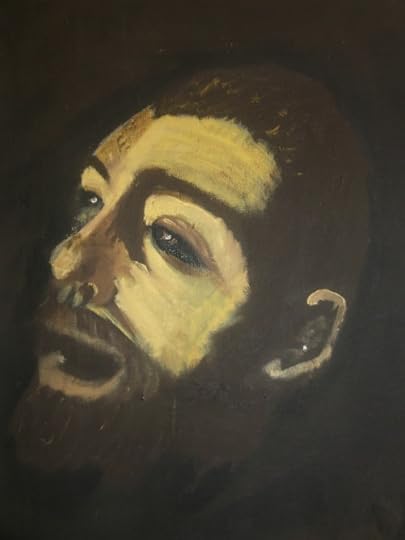

But then I decided to follow Wonka’s advice. So I grew a beard and dyed it black, because that’s how Caravaggio’s beard looked. I cut my hair in his style. I communicated with the spiritual energy of the artist and his lover in a what might be described as a very New Age fashion. I was gripped by fear and panic at night in Malta, as was he, and I got into a little, ahem, trouble in a bar in Naples. He, of course, found trouble everywhere.

The result was twofold. For one thing, it’s a stunningly good novel out in the UK on 5 July. (If I can’t blow my own trumpet, then what’s a blog post for?) But also the extra stages of my research took me so deeply into Caravaggio’s experiences that they changed my own experience of the world.

Caravaggio’s story is usually told as a tale of a brilliant painter whose tendency to violence, leading ultimately to his death at the age of 39, ruined what could otherwise have been a much more productive and happy career. After all my research, I decided the central feature of his life had been something else entirely: Caravaggio was looking for love.

How did I know this? I found it in his paintings. Look at his amazing Madonna with the Serpent and you’ll fall in love, as I did, with Lena, the model for the mother of Jesus. But more than that, behind all the dressing up and role-playing of my research was the sense that Caravaggio’s experience of life had been similar to mine. Not absolutely parallel, because fortunately my father and grandfather didn’t die of bubonic plague when I was six years old as Caravaggio’s did. (There were no recorded outbreaks in Wales in the early 1970s.) But his psychodrama was close enough to mine for me to feel a kinship with him. I’d summarize it thus: like him, I have a deep creative urge that’s rooted in what felt to me, at least, like childhood upheaval; I’ve often been compelled to work for people I despised; our romantic histories are complicated; anger has been… a problem; neither of us lived long in one place; we both found love.

That’s why I didn’t leave my interest in him on the gallery wall. I had to make of him a book, because I believed his story would help me make sense of my own emotions.

Without giving away the story of A Name in Blood, I’ll tell you that Caravaggio’s early paintings show a yearning for love in a man with little control over his life. His middle paintings reflect a sense of the love that he found. The late paintings show a man on the run (under sentence of death) who only then appreciates the depth of his love, both physical and spiritual.

Now that A Name in Blood is about to be published, I don’t have to keep dying my beard. But Caravaggio’s still with me. I hope he’ll soon be with you, too.

Published on June 28, 2012 02:05

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, renaissance, research

June 26, 2012

Forging Caravaggio: Paintings for my new novel A NAME IN BLOOD

About the time Caravaggio was painting his masterpieces in Italy, Miguel de Cervantes observed that "Good painters imitate nature. Bad ones spew it up." Forging seems to me more accurate than imitation. As I researched my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, which is out in the UK on 5 July, I realized I had to learn how to paint with oils if I was to describe the maestro at work. Here are some of my re-forgings (because the original forgeries of nature were by Caravaggio).

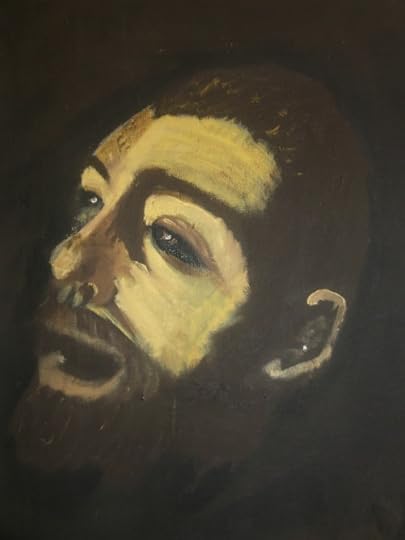

Caravaggio painted his "Sick Bacchus" when he was young and penniless and living what might be described as a sordidly "downtown" lifestyle. I love the way he worked with the unhealthy skin and the rheumy eyes in his self-portrait. It's very wantonly sexual and depraved.

Caravaggio painted his "Sick Bacchus" when he was young and penniless and living what might be described as a sordidly "downtown" lifestyle. I love the way he worked with the unhealthy skin and the rheumy eyes in his self-portrait. It's very wantonly sexual and depraved.

This detail from "Death of the Virgin" is important to the story of A NAME IN BLOOD. It also features Lena, Caravaggio's model and, I think, lover, as the dead woman. Whereas the big test in "Sick Bacchus" is to depict skin, here it's more to do with cloth and depth of field.

This detail from "Death of the Virgin" is important to the story of A NAME IN BLOOD. It also features Lena, Caravaggio's model and, I think, lover, as the dead woman. Whereas the big test in "Sick Bacchus" is to depict skin, here it's more to do with cloth and depth of field.

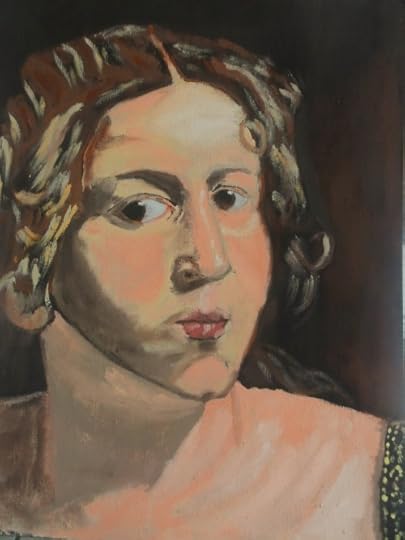

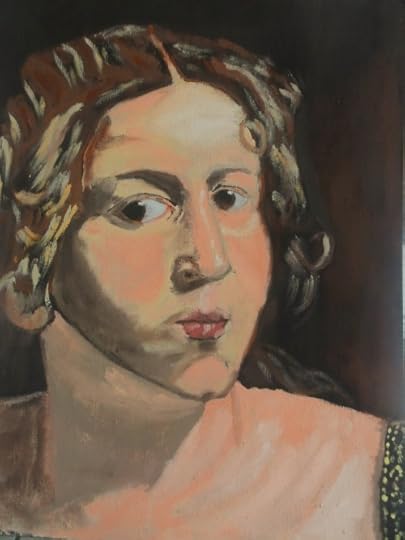

Lena was Caravaggio's model in the "Madonna with the Serpent," which as devoted readers of this blog will know is my all-time favorite painting. I painted it a number of times, working and reworking Lena's face. In this one, she came out looking rather like my maternal grandmother in her younger days...

Lena was Caravaggio's model in the "Madonna with the Serpent," which as devoted readers of this blog will know is my all-time favorite painting. I painted it a number of times, working and reworking Lena's face. In this one, she came out looking rather like my maternal grandmother in her younger days...

Caravaggio's brushwork became swifter as he went on the run from a death sentence. That's why the "Raising of Lazarus" he painted in Sicily is so fascinating to me. I even wrote a short story about it, which you can download if you like as a taster for the novel.

Caravaggio's brushwork became swifter as he went on the run from a death sentence. That's why the "Raising of Lazarus" he painted in Sicily is so fascinating to me. I even wrote a short story about it, which you can download if you like as a taster for the novel. The reason I first conceived of a Caravaggio novel was this painting. It's a detail from "St. Catherine of Alexandria," which I saw in Madrid some years ago at the Thyssen gallery. I suppose I felt seduced by the model, Fillide Melandroni. She was perhaps gulling me, because Fillide was a whore. Or maybe after 400 years, she's no longer just doing it for money...

The reason I first conceived of a Caravaggio novel was this painting. It's a detail from "St. Catherine of Alexandria," which I saw in Madrid some years ago at the Thyssen gallery. I suppose I felt seduced by the model, Fillide Melandroni. She was perhaps gulling me, because Fillide was a whore. Or maybe after 400 years, she's no longer just doing it for money...

One of Caravaggio's final paintings -- perhaps his very last -- is the "Martyrdom of St. Ursula." He had reduced his technique to the barest of light emerging from the shadows. His own face emerges over the shoulder of the saint, craning to see the arrow pierce her breast.

One of Caravaggio's final paintings -- perhaps his very last -- is the "Martyrdom of St. Ursula." He had reduced his technique to the barest of light emerging from the shadows. His own face emerges over the shoulder of the saint, craning to see the arrow pierce her breast.

Meanwhile Ursula's face is highlighted and shadowed in a way that was surely astonishing to Caravaggio's contemporaries. It's in Naples today.

Meanwhile Ursula's face is highlighted and shadowed in a way that was surely astonishing to Caravaggio's contemporaries. It's in Naples today.

Sadly for Caravaggio he never got to meet these two. It's a portrait of my wife and son. I couldn't get my wife quite as lovely as she truly is. But I think I captured the intelligent naughtiness and wit of little Cai.

Sadly for Caravaggio he never got to meet these two. It's a portrait of my wife and son. I couldn't get my wife quite as lovely as she truly is. But I think I captured the intelligent naughtiness and wit of little Cai.

Caravaggio painted his "Sick Bacchus" when he was young and penniless and living what might be described as a sordidly "downtown" lifestyle. I love the way he worked with the unhealthy skin and the rheumy eyes in his self-portrait. It's very wantonly sexual and depraved.

Caravaggio painted his "Sick Bacchus" when he was young and penniless and living what might be described as a sordidly "downtown" lifestyle. I love the way he worked with the unhealthy skin and the rheumy eyes in his self-portrait. It's very wantonly sexual and depraved. This detail from "Death of the Virgin" is important to the story of A NAME IN BLOOD. It also features Lena, Caravaggio's model and, I think, lover, as the dead woman. Whereas the big test in "Sick Bacchus" is to depict skin, here it's more to do with cloth and depth of field.

This detail from "Death of the Virgin" is important to the story of A NAME IN BLOOD. It also features Lena, Caravaggio's model and, I think, lover, as the dead woman. Whereas the big test in "Sick Bacchus" is to depict skin, here it's more to do with cloth and depth of field. Lena was Caravaggio's model in the "Madonna with the Serpent," which as devoted readers of this blog will know is my all-time favorite painting. I painted it a number of times, working and reworking Lena's face. In this one, she came out looking rather like my maternal grandmother in her younger days...

Lena was Caravaggio's model in the "Madonna with the Serpent," which as devoted readers of this blog will know is my all-time favorite painting. I painted it a number of times, working and reworking Lena's face. In this one, she came out looking rather like my maternal grandmother in her younger days... Caravaggio's brushwork became swifter as he went on the run from a death sentence. That's why the "Raising of Lazarus" he painted in Sicily is so fascinating to me. I even wrote a short story about it, which you can download if you like as a taster for the novel.

Caravaggio's brushwork became swifter as he went on the run from a death sentence. That's why the "Raising of Lazarus" he painted in Sicily is so fascinating to me. I even wrote a short story about it, which you can download if you like as a taster for the novel. The reason I first conceived of a Caravaggio novel was this painting. It's a detail from "St. Catherine of Alexandria," which I saw in Madrid some years ago at the Thyssen gallery. I suppose I felt seduced by the model, Fillide Melandroni. She was perhaps gulling me, because Fillide was a whore. Or maybe after 400 years, she's no longer just doing it for money...

The reason I first conceived of a Caravaggio novel was this painting. It's a detail from "St. Catherine of Alexandria," which I saw in Madrid some years ago at the Thyssen gallery. I suppose I felt seduced by the model, Fillide Melandroni. She was perhaps gulling me, because Fillide was a whore. Or maybe after 400 years, she's no longer just doing it for money... One of Caravaggio's final paintings -- perhaps his very last -- is the "Martyrdom of St. Ursula." He had reduced his technique to the barest of light emerging from the shadows. His own face emerges over the shoulder of the saint, craning to see the arrow pierce her breast.

One of Caravaggio's final paintings -- perhaps his very last -- is the "Martyrdom of St. Ursula." He had reduced his technique to the barest of light emerging from the shadows. His own face emerges over the shoulder of the saint, craning to see the arrow pierce her breast. Meanwhile Ursula's face is highlighted and shadowed in a way that was surely astonishing to Caravaggio's contemporaries. It's in Naples today.

Meanwhile Ursula's face is highlighted and shadowed in a way that was surely astonishing to Caravaggio's contemporaries. It's in Naples today. Sadly for Caravaggio he never got to meet these two. It's a portrait of my wife and son. I couldn't get my wife quite as lovely as she truly is. But I think I captured the intelligent naughtiness and wit of little Cai.

Sadly for Caravaggio he never got to meet these two. It's a portrait of my wife and son. I couldn't get my wife quite as lovely as she truly is. But I think I captured the intelligent naughtiness and wit of little Cai.

Published on June 26, 2012 02:01

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, research

June 25, 2012

Writing with Paint: Learning Oils for My Caravaggio Novel 'A Name in Blood'

To research A Name in Blood, my novel about the mystery of Caravaggio’s death, I traveled to all the places where the great artist lived and worked. I visited galleries around the world to stand before his masterpieces, and I read scores of books about him and the period in which he lived. (I don’t expect praise for this; it was no sacrifice, because most of the research was carried out in Italy. It’s a bit like saying, "I had to have sex with a lot of beautiful women to write this book." Except that my wife came with me to do the research, so it only involved one beautiful woman.)

To research A Name in Blood, my novel about the mystery of Caravaggio’s death, I traveled to all the places where the great artist lived and worked. I visited galleries around the world to stand before his masterpieces, and I read scores of books about him and the period in which he lived. (I don’t expect praise for this; it was no sacrifice, because most of the research was carried out in Italy. It’s a bit like saying, "I had to have sex with a lot of beautiful women to write this book." Except that my wife came with me to do the research, so it only involved one beautiful woman.)But none of this would’ve been worth a damn if, when it came to write about Caravaggio at work, I hadn’t had some idea of how to create a painting out of oils.

Trouble was, when I started my research, that was exactly where things stood. In fact, I was pretty sure I couldn’t draw at all.

My brother Dom got the talent with the paint brush in our family, I thought. Inherited from my Dad, who’s an architect and a fine caricaturist. Dom studied fine art and teaches art at a school in London. I was certain that old Mrs. Coneybear, my ludicrously named, Joyce Grenfell-like high school art teacher, had been correct when she glanced over my sketches midway through class and said, “I think you’d better model for the other pupils today, Rees.”

Still, never write anyone off, Mrs. Coneybear. My sister turns out to be rather a good painter, and my mother just made a clay model that looks exactly like the Picasso on which she modeled it. So evidently the whole family has it in them.

Because while I didn’t manage to match Caravaggio (needless to say, that wasn’t my goal), I did find intense pleasure in the concentration and delicacy and even the little tricks needed to paint in oils.

My friend Yael Robin, whose fabulous installations have been shown at the Israel Museum among other fine locations, gave me a few lessons. She emphasized drawing to begin with. I found I wasn’t quite awful, but I knew there was no great talent there.

My friend Yael Robin, whose fabulous installations have been shown at the Israel Museum among other fine locations, gave me a few lessons. She emphasized drawing to begin with. I found I wasn’t quite awful, but I knew there was no great talent there.So we soon moved onto the important stuff. Oils. It transpires that oils are, in may ways, easier than pen and ink, because they’re more forgiving. Draw the wrong line with a pen and it shall remain wrong. Do it with oils and you can scrape it away or smudge it.

In fact, there’s a parallel between oils versus pen and the way I play music. I’ve never been particularly good at playing exactly what’s written on a page of music. I prefer to play in a way that improvises around that musical text. It means I’m not much use at the exactitude of classical music. I don’t much go for the endlessly repeated rock guitar riff either. But I love to diddle around with the notes and make something that’s always new. So too with oils. They’re built up slowly and unless you’re trying to make a photographic representation of something there’s a good deal of leeway with color and line. There’s also time to savor the scent of the linseed oil and turpentine in the room.

That may be why I love Caravaggio’s later works so much. He had moved away from the precision of his earlier pieces. His work reflected his life on the run, but also, I think, the way he felt about life and the soul. Essentially he was painting light, and light often comes at us broken down and inexact.

As you'll see from the examples of my work here (and more I intend to post tomorrow), I made some inexact and broken down (though only in the positive sense of the term!) copies of details from Caravaggio’s works. I’m quite sure A Name in Blood is better for that. I know that I am.

Published on June 25, 2012 04:39

•

Tags:

art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, painting, renaissance