Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "writing"

Me Tweet Now

Because "brevity is the soul of wit," I've decided to start "tweeting" on Twitter, where there's a limit of 150 or so characters to each "tweet." Go to my Twitter profile to follow my "tweets" about my books, the writing process, book tours, mad Middle East news, and other info!

The Writing Life: Matt McAllester

I’m starting a new feature on my blog today—a series of interviews with authors about what it’s like to be a writer. I’ll be asking them the questions readers often ask me, and I’m intrigued to know how they’ll answer them. Be sure to follow this blog so you’ll see what these fascinating writers have to say in the coming months.

It’s a great pleasure to begin this series with my friend Matt McAllester. A Scot, he’s been one of the most intelligent and adventurous foreign correspondents in the world over the last decade. That earned him an uncomfortable stay in one of Saddam Hussein’s prisons, but it also brought him numerous journalism prizes (including a Pulitzer) and the material for his first two books (on Kosovo and on Iraq). Matt’s new book, out this week, is a stunning departure. “Bittersweet: Lessons from my Mother’s Kitchen” is a highly personal account of his relationship with his troubled mother—and the way his memories of her cooking helped him recover the loving, happy times before he lost her to mental illness.

How long did it take you to get published?

I’ve written three books. The proposal for the first one was rejected by every major publishing house. Finally, the wonderful New York University Press bought my proposal, which was about the war in Kosovo. I remember the moment. It was worth waiting for. Even though I’d have made more working at McDonald’s for a couple of months than I did writing that book.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’d mainly recommend reading brilliantly written books and then seeing if you can ever do anything that even gets close. But Orwell is the best, I think, on the process. It’s worth reading his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language. “One needs rules when instinct fails,” he writes, and begins a short list of rules with the following, which I think is probably all any writer really needs to know: “Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.”

What’s a typical writing day?

I wish I had one. But it depends on what I’m writing – a book, an article or just trying to come up with an idea for either. A good writing day produces about 1,500 words. About three of which will be tolerable.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

It’s called Bittersweet: Lessons from my Mother’s Kitchen, and it’s a memoir of my mother, who died over three years ago. She had been mentally ill for much of her life so I was surprised by the awful power of her death. I scrabbled around for a way to make sense of it, to re-connect with her, and I ended up trying to teach myself to cook using her cookbooks. Along the way I learned a lot, I think. I hope the book is full of hope and laughs and moments of beauty and love, as well as the sadness that comes with illness and death.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“It was amazing champagne.” The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway. And borrowed, if I remember correctly, by Geoff Dyer in his excellent Paris, Trance. I suppose I could have fallen in love with a sentence of great profundity. But instead I’m mad about these four frivolous, air-light words of joyousness and rarity.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

There are two snatches in Brideshead Revisited that never leave me. Waugh writes of the “cloistral hush” of Oxford and then this, full of melancholy beauty, with a rhythm that any writer would dream of capturing just once: “Do you remember,” said Julia, in the tranquil, lime-scented evening, “do you remember the storm?”

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Philip Roth, because he is almost without style these days, which I think is an act of will and humility, and suggests that he doesn’t want anything flash to get in the way of what he has to say before he dies. Which, it seems, he feels will be at any moment. Even if it’s not.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

A lot. With my Kosovo and Iraq books, I found it almost impossible to get writing until the research was nearly done. My current book was different. The book became part of the process, really, the writing and discovering and the cooking blending into each other in a way that was new to me.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

She gave birth to me. I thought she was pretty interesting from that moment on.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It’s only happened once, in French, and was jolly nice but I was a bit surprised when my book, which was written in the past tense, appeared in the present tense in French.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I was in San Francisco having a bagel for breakfast. Room service had brought it up. My teeth crunched down on a large chunk of metal. I was pretty annoyed. I took it down to the front desk and held it out in my palm and began to complain that I’d found it in my bagel. At which point my tongue flicked across a huge gaping hole in an uppar molar. British dentistry is, I’m afraid, lampooned in the US for a reason. I rushed off to a proper dentist between radio interviews and slurred my way through the afternoon.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

A manifesto about how we should all live and work outside. I write this while sitting in Manhattan, one of the least exterior corners of the planet, and it doesn’t really seem such a weird idea.

Next up in THE WRITING LIFE: Bangkok nightlife and the dark side of Thailand with Christopher G. Moore.

It’s a great pleasure to begin this series with my friend Matt McAllester. A Scot, he’s been one of the most intelligent and adventurous foreign correspondents in the world over the last decade. That earned him an uncomfortable stay in one of Saddam Hussein’s prisons, but it also brought him numerous journalism prizes (including a Pulitzer) and the material for his first two books (on Kosovo and on Iraq). Matt’s new book, out this week, is a stunning departure. “Bittersweet: Lessons from my Mother’s Kitchen” is a highly personal account of his relationship with his troubled mother—and the way his memories of her cooking helped him recover the loving, happy times before he lost her to mental illness.

How long did it take you to get published?

I’ve written three books. The proposal for the first one was rejected by every major publishing house. Finally, the wonderful New York University Press bought my proposal, which was about the war in Kosovo. I remember the moment. It was worth waiting for. Even though I’d have made more working at McDonald’s for a couple of months than I did writing that book.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’d mainly recommend reading brilliantly written books and then seeing if you can ever do anything that even gets close. But Orwell is the best, I think, on the process. It’s worth reading his 1946 essay, Politics and the English Language. “One needs rules when instinct fails,” he writes, and begins a short list of rules with the following, which I think is probably all any writer really needs to know: “Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.”

What’s a typical writing day?

I wish I had one. But it depends on what I’m writing – a book, an article or just trying to come up with an idea for either. A good writing day produces about 1,500 words. About three of which will be tolerable.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

It’s called Bittersweet: Lessons from my Mother’s Kitchen, and it’s a memoir of my mother, who died over three years ago. She had been mentally ill for much of her life so I was surprised by the awful power of her death. I scrabbled around for a way to make sense of it, to re-connect with her, and I ended up trying to teach myself to cook using her cookbooks. Along the way I learned a lot, I think. I hope the book is full of hope and laughs and moments of beauty and love, as well as the sadness that comes with illness and death.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“It was amazing champagne.” The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway. And borrowed, if I remember correctly, by Geoff Dyer in his excellent Paris, Trance. I suppose I could have fallen in love with a sentence of great profundity. But instead I’m mad about these four frivolous, air-light words of joyousness and rarity.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

There are two snatches in Brideshead Revisited that never leave me. Waugh writes of the “cloistral hush” of Oxford and then this, full of melancholy beauty, with a rhythm that any writer would dream of capturing just once: “Do you remember,” said Julia, in the tranquil, lime-scented evening, “do you remember the storm?”

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Philip Roth, because he is almost without style these days, which I think is an act of will and humility, and suggests that he doesn’t want anything flash to get in the way of what he has to say before he dies. Which, it seems, he feels will be at any moment. Even if it’s not.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

A lot. With my Kosovo and Iraq books, I found it almost impossible to get writing until the research was nearly done. My current book was different. The book became part of the process, really, the writing and discovering and the cooking blending into each other in a way that was new to me.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

She gave birth to me. I thought she was pretty interesting from that moment on.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It’s only happened once, in French, and was jolly nice but I was a bit surprised when my book, which was written in the past tense, appeared in the present tense in French.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I was in San Francisco having a bagel for breakfast. Room service had brought it up. My teeth crunched down on a large chunk of metal. I was pretty annoyed. I took it down to the front desk and held it out in my palm and began to complain that I’d found it in my bagel. At which point my tongue flicked across a huge gaping hole in an uppar molar. British dentistry is, I’m afraid, lampooned in the US for a reason. I rushed off to a proper dentist between radio interviews and slurred my way through the afternoon.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

A manifesto about how we should all live and work outside. I write this while sitting in Manhattan, one of the least exterior corners of the planet, and it doesn’t really seem such a weird idea.

Next up in THE WRITING LIFE: Bangkok nightlife and the dark side of Thailand with Christopher G. Moore.

Published on April 15, 2009 21:22

•

Tags:

journalism, life, matt, mcallester, writers, writing

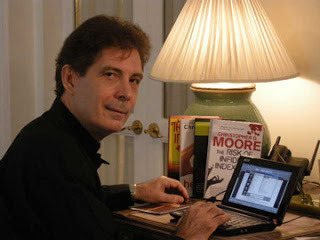

The Writing Life: Christopher G. Moore

Readers love to discover an author whose work suggests they’re a kindred spirit. Novelists, engaged in the often lonely work of writing, enjoy it even more. That’s how I feel about Christopher G. Moore, whose path is in many ways similar to mine (as you’ll see in this interview). Based in Bangkok, he’s the creator of one of the most striking sleuths in crime fiction: Vincent Calvino seems a distillation of all the most intriguing expats you’ll ever meet traveling the world and at the same time utterly unique. Moore's “Spirit House” is one of the most riveting crime novels I’ve read, and I’m delighted that he’s the first fiction writer to participate in “The Writing Life” interview series.

How long did it take you to get published?

My publishing history is a checkered one. My first professional sale was a radio drama to the CBC in 1979, and my first novel (His Lordship’s Arsenal) was published in New York in 1985. After what will soon be 21 novels (The Corruptionist will come out in 2010), I look back and think that I was lucky to start out when I did. It is much tougher now.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

There is a small library full of books on various aspects of writing. Ranging from the mechanics, to the business and legal issues, to self-help. A good web site which includes a page titled Writers Resources which has a lot of useful information about the creative process. Novelist Timothy Hallinan is the brains behind the website. It is hard to disagree with Stephen King’s "On Writing". He says that all writers must be readers. The best education is to read and re-read a diverse range of very good books. I read between 50 to 150 pages a day.

What’s a typical writing day?

The smell of fresh coffee and a long plume of black smoke rising from a burning bus across town. Seriously, there is no “typical” day as any book is a long series of marginally connected events: on the street for research, note making, organizing material, gathering profile information on characters, assembling the cast, selecting an incident that sets off a chain of events much like breaking the rack of ball in pool, fiddling with the outline, working on plot points and structure. Then there is going back to the desk to write the first draft. . .

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

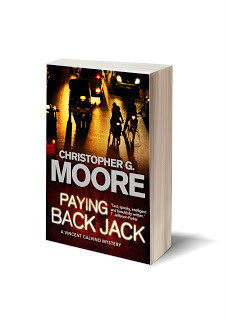

Grove Press will release the hardback edition of Paying Back Jack in October 2009 and Atlantic Books will release it in December 2009. This is the 10th novel in the Vincent Calvino crime fiction series.

In Paying Back Jack, Calvino agrees to follow the “minor wife” of a Thai politician and report on her movements. His client is Rick Casey, a shady American whose life has been darkened by the unsolved murder of his idealistic son. But what seems to be a simple surveillance job pulls Calvino into a quest for revenge, as well as a perilous web of political allegiance. Calvino narrowly escapes an attempt on his life and then avoids being framed for a murder only through the calculated lever-pulling of his best friend, Thai police colonel, Pratt. But unknown to our man in Bangkok, in an anonymous apartment tower in the center of the city, a two-man sniper team awaits its shot, a shot that will change everything.

I’ll let a review place Paying Back Jack in the context of contemporary Thai culture. “It's easy to see why Moore's books are popular: While seasoned with a spicy mixture of humor and realism, they stand out as model studies in East-West encounters, as satisfying for their cultural insights as they are for their hard-boiled action.”—Mark Schreiber, The Japan Times

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

I am told there are quite a few rules. But I never bothered to learn what they are. The private eye novel is mainly thought of as the creation of American authors; notably Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. It is an American invention based on crime in American cities and the social and class structure within which the private eye, police, victims and villains live and die. If there is an American location formula, I broke it in 1992 by setting Spirit House, the first of the Vincent Calvino novels set in a foreign location.

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

To bring the reader into a different culture, different rules, expectations, language, and make it meaningful without overwhelming him/her with obscure references or incidents.

The goal is to make Asia accessible without losing the vitality and history of the place.

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I am fortunate to live in a place (Bangkok) and at a time (political chaos) that provides me with more than enough original material. A third of my fan mail is: Are you safe from the gunfire? Originality can’t be separated from the circumstances in which a writer finds himself/herself. Originality starts at home. If you lead an original life, then by the process of living the material unfolds. I suspect living in Jerusalem that you understand that authors who are living on the edge of where history is moving like tectonic plates, you understand the importance of location, and the challenges to authority, oppression, and inequality. Originality is giving a face to these concepts in real life drama played out where the stakes are high.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“Is execution done on Cawdor?” Duncan, MacBeth, Act 1, Scene 4.

Treason, repentance, pardon and ability to die well all wrapped up nicely. So much of who we are is contained in the exchange between Duncan and Malcolm.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

That’s a tall order to fill. Even within crime fiction there are so many compelling images. The opening of the Quiet American by Graham Greene is a wonderful description of French Colonial police and opium smoking in Saigon. But is it the best descriptive image in all literature? Doubtful. If put against the wall, the firing squad awaiting an order for me to answer or die, I’d opt for the opening of MacBeth. It is hard to beat three witches brewing up a storm when facing rifles.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

Research is the heart of any writing project. Research is part of the job. You push yourself into new situations. Meet new people. Take a different order of risk. You assess as you go along, taking notes, talking to people, strangers, friends, colleagues, locals, foreigners, to get a sense of what people are thinking, suffering, wanting, and scheming to get. Research is also the fun part of the process; you are out from behind a computer and mixing with real people. I am big fan of The Collaborator of Bethlehem: An Omar Yussef Mystery and figure you must have spent a lot of time in the back streets to get the atmosphere right. Novelists should have a journalistic instinct in the field, a poet’s instinct distilling the experience, and a surgeon’s instinct in crafting the words.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

Vincent Calvino emerged from my four years of living in New York

City. I spent time as a civilian observer with NYPD. Calvino is half Italian and half Jewish and narrative often draws upon this ethnic background. The Thai characters arose from various people that I’ve known in Thailand and elsewhere in Asia over the last 25 years.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It’s a bit like a heart transplant. You are unconscious when it happens and when you wake up (assuming that you do), you really only have a vague idea what was done. The main thing is someone else’s heart is pumping your blood. That said, I’ve become friends with my German, Japanese, and Italian translators. And from what I can see, they’ve successfully performed the transplant. I have a Hebrew edition coming out this summer. I understand the translator is an excellent surgeon.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I am fortunate to make a living from my writing. It was about a dozen books into the game that I was able to have sufficient revenue to pay the rent and food bills. Remember, though, where I live (at least in the early years) the cost of living was very little. That is an important factor for any writer. You need to find a place that you can exist with little money. That means places like New York, London, and Paris which once provided such opportunities for artists with meager incomes, now require a law partner’s income to pay the rent.

How many books did you write before you were published?

Three. Lost, gone but not mourned.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

A Russian Mafia thug showed up at a book reading in Pattaya and asked if he could rent one of my books. Guess he didn’t want to lay out the cash investment for a outright sale. It was a public place. I figured he wouldn’t shoot me if I said no.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

A katoey dressed in a Santa Claus outfit on Christmas Eve his small boat washed ashore at Muslim fishing village in Java.

How long did it take you to get published?

My publishing history is a checkered one. My first professional sale was a radio drama to the CBC in 1979, and my first novel (His Lordship’s Arsenal) was published in New York in 1985. After what will soon be 21 novels (The Corruptionist will come out in 2010), I look back and think that I was lucky to start out when I did. It is much tougher now.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

There is a small library full of books on various aspects of writing. Ranging from the mechanics, to the business and legal issues, to self-help. A good web site which includes a page titled Writers Resources which has a lot of useful information about the creative process. Novelist Timothy Hallinan is the brains behind the website. It is hard to disagree with Stephen King’s "On Writing". He says that all writers must be readers. The best education is to read and re-read a diverse range of very good books. I read between 50 to 150 pages a day.

What’s a typical writing day?

The smell of fresh coffee and a long plume of black smoke rising from a burning bus across town. Seriously, there is no “typical” day as any book is a long series of marginally connected events: on the street for research, note making, organizing material, gathering profile information on characters, assembling the cast, selecting an incident that sets off a chain of events much like breaking the rack of ball in pool, fiddling with the outline, working on plot points and structure. Then there is going back to the desk to write the first draft. . .

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

Grove Press will release the hardback edition of Paying Back Jack in October 2009 and Atlantic Books will release it in December 2009. This is the 10th novel in the Vincent Calvino crime fiction series.

In Paying Back Jack, Calvino agrees to follow the “minor wife” of a Thai politician and report on her movements. His client is Rick Casey, a shady American whose life has been darkened by the unsolved murder of his idealistic son. But what seems to be a simple surveillance job pulls Calvino into a quest for revenge, as well as a perilous web of political allegiance. Calvino narrowly escapes an attempt on his life and then avoids being framed for a murder only through the calculated lever-pulling of his best friend, Thai police colonel, Pratt. But unknown to our man in Bangkok, in an anonymous apartment tower in the center of the city, a two-man sniper team awaits its shot, a shot that will change everything.

I’ll let a review place Paying Back Jack in the context of contemporary Thai culture. “It's easy to see why Moore's books are popular: While seasoned with a spicy mixture of humor and realism, they stand out as model studies in East-West encounters, as satisfying for their cultural insights as they are for their hard-boiled action.”—Mark Schreiber, The Japan Times

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

I am told there are quite a few rules. But I never bothered to learn what they are. The private eye novel is mainly thought of as the creation of American authors; notably Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. It is an American invention based on crime in American cities and the social and class structure within which the private eye, police, victims and villains live and die. If there is an American location formula, I broke it in 1992 by setting Spirit House, the first of the Vincent Calvino novels set in a foreign location.

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

To bring the reader into a different culture, different rules, expectations, language, and make it meaningful without overwhelming him/her with obscure references or incidents.

The goal is to make Asia accessible without losing the vitality and history of the place.

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I am fortunate to live in a place (Bangkok) and at a time (political chaos) that provides me with more than enough original material. A third of my fan mail is: Are you safe from the gunfire? Originality can’t be separated from the circumstances in which a writer finds himself/herself. Originality starts at home. If you lead an original life, then by the process of living the material unfolds. I suspect living in Jerusalem that you understand that authors who are living on the edge of where history is moving like tectonic plates, you understand the importance of location, and the challenges to authority, oppression, and inequality. Originality is giving a face to these concepts in real life drama played out where the stakes are high.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“Is execution done on Cawdor?” Duncan, MacBeth, Act 1, Scene 4.

Treason, repentance, pardon and ability to die well all wrapped up nicely. So much of who we are is contained in the exchange between Duncan and Malcolm.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

That’s a tall order to fill. Even within crime fiction there are so many compelling images. The opening of the Quiet American by Graham Greene is a wonderful description of French Colonial police and opium smoking in Saigon. But is it the best descriptive image in all literature? Doubtful. If put against the wall, the firing squad awaiting an order for me to answer or die, I’d opt for the opening of MacBeth. It is hard to beat three witches brewing up a storm when facing rifles.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

Research is the heart of any writing project. Research is part of the job. You push yourself into new situations. Meet new people. Take a different order of risk. You assess as you go along, taking notes, talking to people, strangers, friends, colleagues, locals, foreigners, to get a sense of what people are thinking, suffering, wanting, and scheming to get. Research is also the fun part of the process; you are out from behind a computer and mixing with real people. I am big fan of The Collaborator of Bethlehem: An Omar Yussef Mystery and figure you must have spent a lot of time in the back streets to get the atmosphere right. Novelists should have a journalistic instinct in the field, a poet’s instinct distilling the experience, and a surgeon’s instinct in crafting the words.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

Vincent Calvino emerged from my four years of living in New York

City. I spent time as a civilian observer with NYPD. Calvino is half Italian and half Jewish and narrative often draws upon this ethnic background. The Thai characters arose from various people that I’ve known in Thailand and elsewhere in Asia over the last 25 years.

What’s your experience with being translated?

It’s a bit like a heart transplant. You are unconscious when it happens and when you wake up (assuming that you do), you really only have a vague idea what was done. The main thing is someone else’s heart is pumping your blood. That said, I’ve become friends with my German, Japanese, and Italian translators. And from what I can see, they’ve successfully performed the transplant. I have a Hebrew edition coming out this summer. I understand the translator is an excellent surgeon.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I am fortunate to make a living from my writing. It was about a dozen books into the game that I was able to have sufficient revenue to pay the rent and food bills. Remember, though, where I live (at least in the early years) the cost of living was very little. That is an important factor for any writer. You need to find a place that you can exist with little money. That means places like New York, London, and Paris which once provided such opportunities for artists with meager incomes, now require a law partner’s income to pay the rent.

How many books did you write before you were published?

Three. Lost, gone but not mourned.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

A Russian Mafia thug showed up at a book reading in Pattaya and asked if he could rent one of my books. Guess he didn’t want to lay out the cash investment for a outright sale. It was a public place. I figured he wouldn’t shoot me if I said no.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

A katoey dressed in a Santa Claus outfit on Christmas Eve his small boat washed ashore at Muslim fishing village in Java.

The Writing Life: Thomas M. Kostigen

Thomas M. Kostigen is the most important environmental writer in the U.S. That’s not only because he’s trekked through the Amazon to record how we’re destroying it, or because he climbed into the Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island to…smell how badly it stinks. Or because his ground-breaking New York Times bestseller The Green Book gave us all a checklist for ways to improve the environment around us. It’s also because when he writes about these vital issues he does it with a vibrant touch that brings a sometimes dry scientific and political issue to life. For this reason – if not also for the diversity of his writing experience, as a financial writer, playwright, and screenwriter -- I asked the Santa Monica-based Kostigen to talk about The Writing Life.

How long did it take you to get published?

I actually started writing in college. I interned at a local newspaper that happened to win the Pulitzer Prize while I was working there. So I had these great clips to go along with my degree. From there, well, I continued to publish in newspapers, magazines and wire services. I ghost-wrote a couple of books in my early twenties. I also wrote some plays that were produced, a film, and then turned to books. My first book came a decade after college.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I think Syd Field's book on screenwriting applies to all writing forms because it's about process, structure and tenacity. But really the best books are authors' memoirs or autobiographies.

What’s a typical writing day?

I write every day. Every day! Usually I get informed in the morning. By that I mean reading a lot of newspapers, blogs, and the wires. This helps me wake up and usually sparks an idea or two. I'm an early riser, so by 8 a.m. I am a pot of coffee into the day and cranking away at my quota. I aim for a thousand words a day.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My latest book is entitled You Are Here: Exposing the Vital Link Between What We Do and What That Does to Our Planet. I traveled around the world to very exotic locales to research how we affect the planet by the simple, everyday things we do in our lives. It's great because it's an adventure story as well as a book that has information that can change the world for the better.

How much of what you do is completely original?

I write nonfiction. And while I try to write in my own unique voice, I do rip off Bowles, Theroux, and Chatwin...

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

"For sale: baby shoes, never worn." Hemingway wrote that as supposedly his shortest, short story. And he thought it his best work, or so it's said. Anyway, I like it.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

I think John Irving's description of Owen Meany is up there. He made me hear Meany's voice. Quite a feat for a writer...

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

I'd have to give that to DeLillo. His rhythm is unmatched, and he really shades things nicely.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Rushdie. Who can think like that?

How much research is involved in each of your books?

As a nonfiction writer, I put an enormous amount of research in everything. (I have to footnote.) Memoir editors take note.

What’s your experience with being translated?

I've been translated into about a dozen different languages. My only problem is with Chinese grammar. (They never get it right!) I also learned that my last name in Swedish means "cow path." Hmm....

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I've actually always lived solely off my writing. Now, I live off my books and my freelance journalism. I started making real money after one of my books hit the New York Times best seller list. That moniker gives you lots of cred.

How many books did you write before you were published?

I finished two full manuscripts before I got anything published by a house.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

Ah. Funny story. I was met by my author escort at the airport. She looked exactly like Kathy Bates in Misery. She had double parked her junk car at the sidewalk and got a ticket. An old pizza box was on the passenger seat, which she cleared for me to sit on. After the death ride to my first talk, I came out to find her -- and she had gone. Never saw her again. Crazy.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

The History of the Pogo Stick.

Published on April 23, 2009 22:28

•

Tags:

environment, kostigen, life, writers, writing

The Writing Life: Warwick Collins

The riskiest thing for a writer to do is to try to enter the head of a great genius by making that genius the narrator of a novel. Why? Because if you aren’t a genius of at least similar proportions, it won’t ring true. Think of the tedious melodrama that passed for the life of Michelangelo in “The Agony and the Ecstasy”. When that genius is the greatest writer of all time, the risk to our present writer increases proportionally. Warwick Collins, a British novelist and poet, took that chance when he made William Shakespeare the narrator of his novel The Sonnets. But it was worth it, because Warwick succeeded and The Sonnets is by far the most beautiful novel of recent years. It’s also an astonishing examination of why a writer writes and of how a literary work can change along with the life and loves of the writer. That makes Warwick the perfect author to answer the questions posed here in The Writing Life. He has some surprising ideas.

How long did it take you to get published?

I was fortunate that my first book, a sailing thriller called Challenge, was bid for by eight publishers. It was eventually published by Pan/Macmillan

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I don’t know any books on writing that I would recommend. The best way to learn about writing, I suspect, is to read as much good literature as one can.

What’s a typical writing day?

I’m one of those annoying people who feel fresh when they wake up, so I try to put in a minimum of one and a half hours before breakfast. If I feel up to it, I’ll return at various stages in the day. But I find writing is quite a nervous and energy-sapping process, and often I find that after my morning efforts I need the rest of the day to recover and be ready for the next early morning attempt on the blank screen.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My most recent novel The Sonnets is an attempt to describe Shakespeare’s life from 1592-4, the years in which the London theatres were closed by threat of plague, and the 29-year-old Shakespeare was forced back on his own resources. He was fortunate to find a patron in the young Earl of Southampton. Those were the years in which many of the other playwrights died of violence (like Marlowe, killed in suspicious circumstances in a pub or Kyd, put on the rack) or of poverty, like Greene. Shakespeare emerged from those turbulent times to become the leading playwright on the Elizabethan stage. During those plague years, too, it is widely believed that Shakespeare wrote the bulk of his great sonnet sequence. I’ve integrated 32 full length sonnets into the text of my novel. I also added two “imitation” sonnets – both carefully flagged up as imitations, by the way. It was fascinating attempting to compose those imitation sonnets, and I think it helped me to gain an insight into the way sonnets are constructed, and how the very tightly defined form imposes on the content.

How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write, and how much is as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

So far I’ve always been criticized by UK and American corporate publishers for NOT writing to a formula and for constantly changing both the subject matter and the style with which it is approached.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

For prose, Cormac McCarthy; for dialogue, Elmore Leonard.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Philip Pullman, for His Dark Materials trilogy.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

I thoroughly recommend writing the first draft of the book before one does detailed research. This appears the wrong way round, but I believe it is still vastly more effective. Knowing the subject matter of the novel greatly narrows the research area, and the result is that the research in that area can be highly focused and detailed. The Rationalist and The Marriage of Souls were both set in the eighteenth century, about which I knew very little. I could have spent years reading up about the eighteenth century and only used a fraction of my laboriously acquired knowledge in the novels. But, for example, once I knew that Silas Grange, the protagonist, was a physician of “modern” outlook (for the times), I could research the area of medical practice in far greater depth than otherwise would have been the case, and virtually all of it was useful.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

A number of writers I have talked with are inspired by people whom they’ve met. In my own case, I get interested in an idea first, and after that it’s more a matter of trying to build up a character from the circumstances. In the case of The Rationalist, for example, some of the few things I did know about the eighteenth century were that it was a time of loss of religious faith, of the rise of science, and the loosening of sexual mores – in that way a reflection of our own times. It seemed interesting to me if Grange had elements of a modern scientist in his character, was perhaps a touch obsessive, pragmatic, rational, thorough, and if the femme fatale who brought him down, Mrs Celia Quill, was something of a proto-feminist.

What’s your experience with being translated?

So far pretty good. I’ve been fortunate that my foreign language publishers have chosen good translators.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I have lived mostly off my writing for about 20 years, but I’m unusual in that most of my income has come from foreign language translation/publication, and from occasional forays into screenwriting.

How many books did you write before you were published?

My first published work was a series of poems published in the magazine Encounter. I wrote two novels before Challenge was published. They both seem to me now to be somewhat juvenile, and I would have no interest in either of them being published.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

During a tour of Germany for the German edition of my novel Gents, my publisher was based in Munich. Gents is a novel about three immigrant West Indians who run a urinal in London, and spend much time trying to suppress the “cottaging” (sexual activity between men) which goes on in the cubicles. Each of the West Indian main characters is religious and something of a family man, too, so this background activity is somewhat shocking to them. Although I am not gay myself, Gents was fortunate to receive favorable reviews from the gay press, and from West Indian reviewers. I don’t know whether my German publisher, a leading feminist, was being mischievous, but while on book tour she booked me in at a famous gay hotel in Munich. That was a very interesting experience.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

The weirdest idea I have had for a book was Gents, and I did publish it, and am glad that I did.

The Writing Life interview: Gregg Hurwitz

Gregg Hurwitz is the kind of guy other guys would like to be. Hollywood handsome, an accomplished athlete with a tremendous academic record, successful in his chosen field. He’s also the kind of writer other writers would like to be. His thrillers are intricate, thought-provoking, and breathlessly paced. His new book Trust No One, which I reviewed last week, will be out in June, and it’s red hot. Gregg took time out from the busy publicity schedule in advance of his new novel to tell me his views on writing and the life he lives around it.

How long did it take you to get published?

I was very fortunate—more fortunate than I knew at the time. I wrote my first book in college, revised it while getting a one-year masters (in Shakespearean tragedy—hurray for useful degrees!), and sold it shortly after. So I never had to find respectable work.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I’d recommend reading lots of novels.

What’s a typical writing day?

Up at 7, writing by 8. Work all day. Finish between 4 and 8, depending on deadlines. Sometimes a night shift too if deadlines are threatening.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

Well, I’ll give you a rundown of the first chapter.

Nick Horrigan, an average guy, awakens in the middle of the night when he thinks he sees a watery blue light along his ceiling. He blinks, and it’s gone. He gets up, rubbing his eyes, crosses into the main room, and looks through the sliding glass door onto the balcony. A black rope is hanging over the lip of the roof and lies coiled on the balcony floor. He opens the slider, steps out, closing the screen behind him.

Down below he sees dark sedans lining the curb on either side, and cop cars with their lights now turned off. Before he can react, the rope twitches, and a guy clad in full SWAT gear rappels off the roof and—not seeing Nick—hammers him in the chest with both boots. Nick soars back into his apartment, ripping the screen from the frame, and lands on his back. His front door flies out of the frame like a hurricane hit on the other side, and slides to within an inch of his nose. And before he can catch his breath, a full SWAT team storms the apartment.

The lead agent grabs him, asks, “Are you Nick Horrigan?” Nick still can’t catch his breath, so he nods. They shove a photo in front of his face. “When’s the last time you’ve had contact with this man?” Nicks says, “I’ve never seen him before.” They tug him to his feet. He’s barefoot, in pajama bottoms. He’s dragged outside. Cop cars everywhere. Neighbors lining the sidewalk. A loud thrumming shakes the air and then the palm trees behind his building light up. A helicopter rolls into view and sets down on the end of his cul-de-sac. He’s dragged toward it, and finally he stops, says, “You can’t just take me. Where the hell am I going?”

And the lead agent replies, “A terrorist has just seized control of the San Onofre nuclear power plant. He’s threatening to blow it up. And the only person he’ll talk to is you.”

And there we end chapter one. I think the thing about this book that made it so much fun to write is its velocity. I really wanted it to move like a freight train, while not sacrificing character. So what took the most work was to keep that pacing tight while also delving into character. I hope readers will find I was successful.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

That’s an interesting question. It’s very hard for me to distinguish because I’ve always been drawn to genre. And to structure. I love Shakespeare, for instance, and he was clearly working within very clearly defined conventions and structures, but also as original as one can get. For me I don’t break it down the way you lay out above. I find a story that I can sink my teeth into, and then I try to let the story guide me to its logical shape. The metaphor I think of is lying down on a towel at the beach. At first it’s uncomfortable and you sort of settle your body down, move the sand from beneath your head, find a comfortable mold for your body. That’s the process of getting to a good story—a lot of squirming and adjustment so it can lie comfortably.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

Molly Bloom’s soliloquy at the end of Ulysses, ending with “Yes I said yes I will yes.” Because if you have to pick one sentence, why not choose one with great stamina? Also, I think the thawing of that relationship is so human and intimate and wonderful, and here, her remembered lovemaking is so tender after everything they’ve been through. Plus, what better way to convey an orgasm?

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

Benji in The Sound and the Fury: "It was two now, and then one in the swing." The greatest description of a kiss, from Benji’s limited perspective.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Boy, I don’t know. I haven’t read everyone. Louis Begley is pretty staggering. To jump to non-fiction, Christopher Hitchens makes my jaw drop. And James Wolcott is the perfect social commentator. For crime fiction, it still goes to Thomas Harris (for Red Dragon), though Motherless Brooklyn also blew my hair back; after writing that, Lethem must’ve taken a victory lap.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

I am tempted to answer with a name from politics.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

A good amount. For various books, I’ve gone undercover into mind-control cults, sneaked onto demolition ranges with Navy SEALs to blow up cars, gone up in stunt planes. When I’m dug into a story, my foolishness knows no bounds.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

For me, when character collides with plot is when I know I have a book. And so I thought of Nick waking up to this SWAT team storming his apartment in the middle of the night—your classic Everyman in an impossible situation, like Jimmy Stewart in a Hitchcock flick. And then I thought: what if something had happened in his past that, rather than this being a surprise out of the blue, was something he always feared would happen? So that when they drag him in his boxers to the waiting helicopter, while he knows nothing about what’s happening, he DOES know that he’s been marked in a manner since his childhood.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

Sandwich boards. Or hide hundred dollar bills in the pages.

What’s your experience with being translated?

I have great relationships with my foreign publishers. I went to Moscow and St. Petersburg recently for book festivals, which was a blast. But what’s funny is: when you’re translated into a language you can’t read, it’s like collaborating with someone when you can’t see the outcome. A writer is very reliant on the talented men and women who translate his work—you go on trust and pray that they have a good ear for the cadence of your writing. And if they don’t, you’ll never know!

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

Yes. I’ve been quite fortunate. I’ve been writing full-time since I sold my first.

How many books did you write before you were published?

I sold my first, not counting Willie, Julie, and the Case of the Buried Treasure (written in third grade). I’m still shopping that one with little luck.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I was in Minneapolis the day of the bridge collapse, and I was supposed to be going over the bridge at that moment, but my driver took a detour to dodge traffic.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

Baseball haiku.

The Writing Life interview: Barbara Nadel

One of the jobs authors are required to perform to help promote their work is the strange task of procuring from other authors something called a “blurb”—the praise you’ll find on the back cover of books. They ought to come from authors whose readers might also be interested in your book--that's the idea. In 2006, when I sent out advance copies of my first novel “The Collaborator of Bethlehem,” I had no doubt I wanted one to go to Barbara Nadel, winner of the Crime Writers Association Silver Dagger the previous year. Her fabulous series of novels about Istanbul detective Cetin Ikmen delves into a society that we think we know a great deal about – only to demonstrate how much more complex is the reality. That’s one of the things I was trying to do with my Palestinian detective Omar Yussef. I’m pleased to report that Barbara recognized that, and she was kind enough to read and comment (favorably!) on my book. She’s published 11 terrific Turkish novels and is about to publish a new novel in her other series, in which the hero is a London undertaker. The two series are rather different and make varied demands on this intelligent writer, so I thought it’d be fascinating to ask her about The Writing Life.

How long did it take you to get published?

I first started trying to get published in 1992. At that time the notion of a mystery book, much less a series set in Turkey, was rejected as almost laughable. I’ll be honest, I gave up and put my first book Belshazzar’s Daughter in a drawer for 7 years. The only reason I ever took it out again was because in 1999 I was, yet again, totally broke and I thought, ‘why not give this old thing one more go? Maybe someone will give me some cash?’ So I sent it to an agent who, on this occasion, liked it. The next thing I knew I was involved in a three book contract! Now ten years on, I write two mystery series; the Inspector İkmen stories set in modern Turkey and the Francis Hancock mysteries set in 1940s London.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I have to admit that I’ve never read any!

What’s a typical writing day?

I live in the north of England and so my first task of the day is to look out of the window and see what the sky is doing. That done, I try to get to my desk by about 8am and then work through until lunchtime. I don’t generally do lunch – a legacy of past chain-smoking – but just have a cup of tea and maybe, just occasionally, a cigarette. I’ll then work through until about 5 or 6pm. I don’t do this every day but try to work this schedule Monday to Friday if I can. I have pretty heavy family commitments and so it’s not always possible.

Plug your latest book. Why is it so great?

I have two books out next month, one paperback, an İkmen mystery called River of the Dead, and a new Hancock hardback called Sure and Certain Death.

River of the Dead sees İkmen and his protégé Suleyman, in pursuit of an escaped prisoner. Yusuf Kaya is a murderer and drug dealer and when he escapes from prison in İstanbul it is suspected he has had help. Also because Kaya’s home town is in eastern Turkey it is strongly suspected he has gone back there. And so while İkmen pursues the investigation in İstanbul, Suleyman flies out to the eastern city of Mardin. There he finds not only drug dealing, gun running and the threat of terrorist attack, but also an exotic mix of people including Kurds, Suriani Christians and those who believe in an ancient snake goddess, the Sharmeran. This book came about as a result of a trip I made out to Mardin in 2007 and is I hope imbued with the same sense of magic and unreality that I found there. That said River of the Dead is also a tough book which address very real issues I talked to people about in Mardin, like the Iraq war. I think it’s great because although it is a crime story it is also a social commentary as well as, hopefully, introducing some people to the glories of south eastern Turkey.

Sure and Certain Death is about a series of killings that take place in the London Borough of West Ham in 1941. Middle aged women are being attacked and eviscerated. Local people start whispering about Jack the Ripper being on the prowl again. One such victim is discovered in a bombed out house by undertaker Francis Hancock. A veteran of World War I, Francis suffers from shell-shock which means that sometimes he doesn’t always know that what he is experiencing is actually real. But soon the murders come close to home and he finds himself fearing for his own sister. Sure and Certain Death is a story about World War 2 that has its murderous roots in the darkest corners of Word War 1. I think it’s a good book because it is not either an obvious murder story or a straightforward story of the London Blitz. My father experienced the Blitz when he was a child and although the Hancock books do tell of the heroism of that time, they also aim to tell it like it was too. Francis Hancock’s world is therefore one of privation, dirt, anxiety and sometimes madness.

How much of what you do is dictated by genre formula, personal formula or complete originality?

My aim is always not to write to formula but to produce something fresh every time. However within the crime/mystery genre there are certain constraints, like having a ‘tidy’ ending. Not to do this is unsatisfying for the reader, even though I do sometimes want to reflect the sheer messiness of real life. In addition series characters do have back stories which have to be addressed in some form in every book and so formula could be said to apply there too. In the main however I don’t write to formula.

What’s your favourite sentence in all literature and why?

From Great Expectations by Charles Dickens. These are the first words Miss Havisham ever speaks to Pip. They sum up both the bitterness and the tragedy of her situation perfectly.

‘This,’ said she, pointing to the long table with her stick, ‘is where I shall be laid when I am dead. They shall come and look at me here.’

She knows that her relatives will only ‘come and look’ at her. They won’t grieve. They are only interested in her money. All this is conveyed so well in this cold little sentence.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

Quite a lot, although of course it does depend on the book. For River of the Dead I had to go to Mardin and its environs and talk to people so that was pretty full-on. With the Hancock series of course I have to do historical research into aspects of World War 2 every time. Enjoyable but time consuming.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before you could make a living at it?

For the first 6 years of my writing career I couldn’t make my living just from my books. I had a day job in a psychiatric hospital and wrote at night and at weekends. Since the Hancock series began however (4 years ago) I have (just) been able to survive on writing. However it’s not easy and I do have to supplement my income by writing short stories and bits of journalism.

How many books did you write before you were published?

I had one academic book published before ‘Belshazzar’s Daughter’ but no fiction. Not that I didn’t try. I wrote two books which I haven’t had published. Goodness knows if they’ll ever see the light of day!

What’s the strangest thing that ever happened to you on a book tour?

Meeting an old man who was called Mr İkmen and then, not twenty four hours later, seeing a Turkish policeman who looked just like my internal vision of İkmen’s protégé, Suleyman!

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

A horror story about a Victorian side-show man who kills people and then places them in sentimental tableau which he charges the public one penny to view. Ghastly and weird and clearly the product of a brain that is not what it should be. Mind you, Goths would like it I am sure!

Early Morning Conspiracies: The Writing Life interview with David Liss

David Liss is the author of classics of historical fiction from his Edgar Award-winning debut A Conspiracy of Paper, which was rooted in his academic studies, through the fabulous tale of the Portuguese Inquisition and the Amsterdam commodities exchange, The Coffee Trader, and on into his compelling portraits of real historical figures like Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr in The Whiskey Rebels. It has always seemed to me that his masterful use of the historical mystery allows him to get to the heart of political and social issues that remain with us today – anti-Semitism, the morality of finance and of punishment, and much more. That’s why I asked him to tell me about his Writing Life. It turns out a lot of it takes place while most writers are asleep…

How long did it take you to get published?

Even though it felt like a very long time while it was happening, the process actually went very quickly. I sent out a ton of query letters and received a ton of rejections. About the same time, however, an old friend of mine published her first novel, and she offered to show my manuscript to her agent – who then became my agent. After that things went very quickly. I started sending out my first letters in March of that year. I had a contract in August.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

When I teach creative writing, I often use On Writing by Stephen King, though part of the reason I use it is because -- while he says some very smart things about writing -- I disagree with about a quarter of the advice he gives. I think it is important to recognize that there is no one right way to do things, and that in the end the only real rule is that each writer should do what works for him or herself.

What’s a typical writing day?

I am an early riser, and I can only do my best work in the AM hours. These days I get up at 4, go to the gym, come back home and get the kids ready for school. I drop off my daughter and go to a coffee shop with my laptop and write until about noon. After that, I spend the day running errands and doing research.

The Whiskey Rebels is the only book I’ve ever written under deadline, and at once point I realized I had far more work to do than I had time to do it in. I started getting up at 3 every morning, working until the children woke up, getting them off, and then having another writing session. I ended up doing this for a year, and though it was a hard year, it was also a very productive time.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

The Devil’s Company will be published in July. It is essentially a novel about the 18th century origins of the modern corporation. In this case I am writing about the British East India Company at a moment when it has to change its entire corporate model. We tend to associated the East India Company with tea, but in the early 18th century it was best known for its textile imports. In the 1720s, Parliament finally caved to pressure from the native wool and silk-weaving industries, which were suffering from having to compete with cheaply made foreign imports.

Like several of my previous novels, this one deals with a pivotal moment in economic history, but I also like to emphasize that I don’t write dry, ponderous books. I see my first responsibility as entertaining the reader, and I always do my best to write a story that is engaging, exciting, suspenseful, often funny and filled with engaging characters. My second responsibility is to say something worth saying.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

Some, but not much. I don’t write within the genre mystery format any longer because I found it too constricting. I consider what I write now to be more in the thriller camp, and the only real requirement of that genre is that the material be fast-paced, exciting, and suspenseful – which I think ought to be true of pretty much any traditional narrative.

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

I primarily write historical fiction, but that is always my choice. My publisher may not like it, but they know I will always write what I wish to write. I probably could have made choices early in my career which would have made me a more commercial writer, but I feel very lucky that I can make a living doing what I love, and I get to write the books I want to write. Also, I am very open to branching out. I recently wrote a short story for an anthology about zombies, and I just finished my first comic book script for Marvel.

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Some of my books are entirely unlike any of my other books. The Devil’s Company will be my third novel with a continuing protagonist, Benjamin Weaver, but while the first two were very much like genre mysteries, this one is not. I do not reinvent the wheel each time, but never want to be guilty of writing the same book over and over again.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

I don’t really believe in exclusive favorites, but one thing that comes to mind is the final sentence of Paradise Lost:

The World was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence their guide:

They hand in hand with wandering steps and slow,

Through Eden took their solitary way.

I know it is a sign of mental illness, but I love Milton, and I think this is the most powerful conclusion to any long work in English letters.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

My vote is for David Mitchell.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

No one does the twists and turns better than Harlan Coben. Sometimes his choices verge on the totally implausible, but he provides such a great ride that I honestly don’t care.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

Depends on the book. If I am writing about 18th century Britain, I’ve already done most of the leg work, and those books only require specific research into the particular topic of the book. If it is set in a different time and/or place, then I have to learn an entirely new culture, and that is a fairly demanding and time-consuming process. I always like to do enough research to get me to the place where what I don’t know is no longer keeping me from writing the story I want to tell.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

Novels almost always begin for me with an idea for an opening scene. I think of something dynamic and exciting, and then I try to decide who the characters are who would inhabit this scene and the world in which it belongs.

What’s your experience with being translated?

Right now I have to say pretty good. I am writing this interview at an outdoor café in Piacenza, a town in northern Italy, where I am attending an arts festival. I became involved with this festival thanks to my Italian translator, one of the organizers. I’ve been translated into about 2 dozen languages, and I do better in some countries than others. Someday I would like to be translated into Icelandic, but so far, no luck. I have a theory that if I include a character from a particular country in a novel then the rights will be picked up there. The only one of my novels to be translated into Turkish, for example, is The Coffee Trader, which includes a very minor Turkish character. I plan to put an Icelandic character in my next novel in order to test this theory.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I’ve been lucky enough to be able to live off my writing since my first book.

How many books did you write before you were published?

I attempted a novel right after I graduated from college, but it was really, really bad. A Conspiracy of Paper, my first novel, was the first book I tried to write when I gave it another shot ten years later.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

Once I flew into Milwaukee and as soon as I got to my hotel I went out for a run. It was a beautiful day, and I was running by the water, so I lost track of time for a while. When I decided I needed to return to my hotel in order to get ready for my reading, I realized suddenly that I did not remember how to get back to my hotel or what its name was.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I plan to publish all my weird ideas.

Published on May 17, 2009 07:14

•

Tags:

antisemitism, coben, commodities, crime, david, fiction, finance, harlan, historical, inquisition, king, life, liss, milwaukee, mitchell, stephen, thrillers, writers, writing

The Queen of Quirky: The Writing Life interview with Tama Janowitz

Tama Janowitz has always been great at first lines (Remember her Slaves of New York opened with this: “After I became a prostitute, I had to deal with penises of every imaginable shape and size.”) Her new novel, they is us, will be out in September in the U.S. (It’s already published in the UK by The Friday Project) and she strikes again with a first paragraph that seems to carry all our fears of a technologically mutated future and our present discontent with a changing world: “Years pass. There are still thimbles and Unitarians. The world is the same as it has always been, maybe a little worse. It’s a beautiful summer day, kind of, although violent electrical storms are predicted for later – if not that day, then sometime. And the news, too, is much the same: 40 percent of people can’t sleep; a type of bustard believed to be extinct has been found; war continues.” It’s an astonishing novel, its weird quirkiness a mask for a powerfully grounded nuts-and-bolts skewering of modern society. You may gather from Tama’s interview with me that she could’ve easily titled the book dystopia is tama. In fact, she unveils some astonishing points about how difficult it is simply to life a Writing Life.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

I always liked to read books on ‘how to write’; for some reason I found them very soothing and encouraging. I could not recommend one in particular, it was a long time ago but I did used to buy them. I think John Brain wrote one? I liked it.

What’s a typical writing day?

I used to be able to get up and get to work right away and I would give myself x number of words or pages to write. Every year it took me longer and longer and more and more procrastination on my part and fewer words. I find having a computer helps in some ways – you can change a character’s name just by typing ‘replace all’ but at the same time I keep checking my e-mail etc. and finding other things to do before settling down which nowadays is usually not until close to noon. I used to write seven days a week. Now I do not write on the weekends; I am like a huge slug or larvae, in bed and surrounded by small dogs (I have eight) and they want to go out but either it is too cold or too hot or it is raining or . . .

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

This book is called they is us. I like the pictures in it because I chose them. I like to color them in with soft color pencils. And I like to put some sticky mirrored paper on the front and back covers. You can buy this kind of paper on Canal Street in New York! They have all kinds of shiny paper in this store. I like the type that is silver with kind of holographic little squares. Also I like that it is a book with a front cover and a back cover and pages in between, that way I can look at it and think to myself, hey I wrote a book! And I got it published! Sometimes that makes me feel kind of good.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

I would like to write a genre novel that would be popular but I don’t know how and it wouldn’t turn out right anyway or probably I would get bored and not finish it.

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

I sure wish I had a formula and could stick with it. I don’t know what the formula would be.

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I don’t think it possible to be completely original and there is no such thing since we have to use things like ‘“oh no, you’re kidding!” he said.’ But I hope I can be a little bit fresh in my use of language or characters and style.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

There have been many great stylists and all different, Nabokov who could sling a sentence like a rope of rubies and strangle you with its brilliance. Or Virginia Wolff – the first to write as if really inside the person’s or people’s heads. But one kind of style does not negate another and as for today’s greatest stylist, I suppose there could be many, I do not keep up with or read that much current fiction.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

I do not know what compels me to write. I do not have a childhood pain or at least no more than anyone else. I do not like to write and I do not make any money off writing and I do not have any readers but a few and I have many nasty things written about my writing and I find writing depressing and boring but I keep writing and I do not know why.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

I really would not know. My first book American Dad did not sell any copies and when my next book Slaves of New York was published whenever they telephoned me from the publisher to say so and so wanted to interview me, I said, ok, because it had been so hard to sell my second book since my first book hadn’t sold and I kept writing books but nobody would publish them and so I switched to short stories because they took less time to write and get rejected but then the New Yorker started publishing me and then a company did want to publish a book of my short stories. So I always did what they asked me to do, they hired a company to make a short video of me and then I kept doing whatever they asked me to do. Then I did some advertisements. I was broke and I had only received three thousand five hundred dollars for that book. However then the press and people said I was out for publicity. And they said ‘a real writer would not do advertisements.’ There were editorials in the newspaper about my evilness. However nowadays not only are many writers making their own videos for Youtube to promote their books, over the many years before me authors who did commericals/adverts were: Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Steinbeck, Hemingway (whisky I think) Lillian Hellman; John Irving (am-ex); Norman Mailer (Trump Airline) and then after me Joan Didion did an ad (The Gap) and many others. Then a nasty little writer did an interview and called me a ‘whore’ for doing adverts. He said he had been asked to do adverts but he would not do so! Of course he had many many rich wives to support him, so I guess he didn’t need to!

What’s your experience with being translated?

I do not speak or read another language fluently enough to be able to tell how well or poorly a book of mine has been translated. Once someone began reading Kafka’s Metamorphosis in original German and I was stunned at the sound of the words and how much richer it sounded in German than English. I know that the couple who recently did a new translation of ‘Anna Karenina’ gave that book a whole new life and probably a lot of books have lost a lot in translation – people sometimes tell me ‘such-and-such’ a translation of one of my books was good or bad. It is hard for me to care however since in all these years I never got any royalty check beyond the original one or two thousand for initial rights of a book being sold. I figure what you get up front is all you are ever going to get; but since I do not take an advance but must write on my own first, I do not get any money – because publishers want to give you money based on an ‘idea’ but are always disappointed by what you end up writing. The only exceptions to this are a first time novelist who has already finished a book but does not have a track record – publishers will jump on this – or a book from the p.o.v. of a different culture – say, an Iraqi growing up in London or a Chinese person in Canada or . . . etc. etc. These books – let’s say, a girl from Jamaica writing about her family’s history and moving to the USA – are what get the Pulitzer and other prizes these days.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

I made a living from my writing for about three years. Before that I just kept at it and would get very tiny amounts here and there from small prize or small publication; then after I no longer made any money fortunately my husband did start to make money and he has been very, very kind and supportive emotionally and financially – I still have hopes that someday I might once again make a few dollars. For at this time had I spent the last 28 years working at McDonalds I would have earned more on a per annum basis.

How many books did you write before you were published?

I did write a few books before I got published as I had read that Doris Lessing wrote five books before she got ‘the first’ published. In my case though my first book American Dad did get published first in 1981, however, then some of the other earlier books I put into a drawer, I chopped up into stories

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

Many things have happened but one thing that stands out is I was in Minneapolis and there were three people who came to hear me read/speak and there were many, many chairs set up and the staff disappeared and then the fourth person arrived and he resembled a murderer or serial killer and he sat in the front row and he had a metallic suitcase and I began to read and he opened his suitcase and I thought now he will take out a gun or knife. But instead he took out a book and began to read it. But it was not my book and he was not reading along to himself with what I was reading. It was a completely different book by a different person.

Another time I had a publicist from the company who sent me out on a ‘book tour’ only she did not book me in any media or readings and so I went from city to city picked up by an escort and then sat in the hotel; sometimes the escort would wonder why the publicist had not booked me on various tv shows/interviews etc that would have been happy to have had me. When I mentioned to the publicist that I wasn’t doing anything but sitting in my hotel she began to scream at me at the top of her lungs that it was all my fault.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I do not have weird ideas, I have regular ideas but they don’t come out normal.

Acid attacks, crucifixion, and a new Patricia Cornwell: Caro Ramsay's Writing Life interview

Caro Ramsay’s debut “Absolution” is one of the most disturbing thrillers you’ll ever read. It features a beautiful woman who’s the victim of an acid attack and a series of disembowelments in the “Crucifixion killings” of young women. Caro’s also from one of the roughest neighborhoods of Glasgow, where she sets her novels. Would it surprise you to learn, then, that’s she’s an extremely charming person? We met last year at an awards dinner in London (where she trained as an osteopath) and I’m delighted that she agreed to answer the questions I pose in The Writing Life. (For American readers, osteopathy is a British form of medicine involving manipulation of the muscles and bones. It hasn’t really taken off in the U.S. It’s a bit like what a U.S. chiropractor does. Although I’m sure I’ll get emails now from outraged osteopaths and critical chiropractors who disagree. In any case, it doesn’t involve crucifixion, although my mother who once had to visit an osteopath for a slipped disc said it felt like it.) Out earlier in May in the UK, Caro’s new book “Singing to the Dead” was, for many of her fans, a long time coming – not that she’s been lazy, it’s just that a year and a half is a long time to wait in the world of crime fiction! But the response from readers, who’ve already made it a bestseller in Scotland, shows that it was worth it. She’s often compared to fellow crime-writing Scot Ian Rankin – he’s Edinburgh to her Glasgow. With her own medical background, a better comparison might be the medical thrillers of Patricia Cornwell.

How long did it take you to get published?

The first thing I wrote was picked up by an agent and sold to Penguin so it was instant for me. It was never a plan of mine to become an author. I was lying in a hospital bed unable to move for a long time and wrote 250,000 words because I was so bored. Those words became two novels - Absolution and Singing To The Dead.

How long did it take you to get published?

The first typescript I sent away was accepted by an agent and subsequently sold to Penguin. My agent does do a fair bit of in-house editing and I think they saw in that first draft somebody who had a gift for writing but who had no idea how to put a novel together. But once I had learned that (very hard) lesson the book was immediately offered to Michael Joseph at Penguin and they immediately accepted. So compared to other authors I was very lucky. The lucky thing was having a very good agent!

Would you recommend any books on writing?

None that I have found really helpful. I think I found it of more benefit to read a lot in my own genre, finding out what worked for me and what didn’t. My philosophy is to write what I would want to read!

What’s a typical writing day?