Matt Rees's Blog, page 5

September 23, 2013

Caravaggio inspires Pope Francis

Pontiff cites Caravaggio's finger of Jesus pointing at him

The painting that first truly made Caravaggio's reputation was The Calling of St. Matthew, one of three works about the saint he completed for the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi in central Rome. The latest declared fan of the work is Pope Francis, who said in his important interview last week, "That finger of Jesus, pointing at Matthew. That’s me. I feel like him. Like Matthew. This is me, a sinner on whom the Lord has turned his gaze."

That has made some headlines because the pope said he was a sinner. It's part of the gentler idea of the church's role he posited in the interview, a stance in contrast to the pretty fearsome growls his two predecessors turned on the world.

It's also remarkable because Caravaggio has become a painterly symbol of things countercultural. Not only was he probably bisexual, a killer, who consorted with, slept with and used whores as models. He went against everything the conservatives of his time agreed made painting beautiful and worthy of display in churches to inspire the faithful. (I imagine Ratzinger never made a special stop at The Deposition of Christ in the Vatican Museum. I did, as you can see, and it's amazing.)

So what was important in its day about The Calling of Saint Matthew? Here Caravaggio thinks about it in my novel A NAME IN BLOOD:

The painting that first truly made Caravaggio's reputation was The Calling of St. Matthew, one of three works about the saint he completed for the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi in central Rome. The latest declared fan of the work is Pope Francis, who said in his important interview last week, "That finger of Jesus, pointing at Matthew. That’s me. I feel like him. Like Matthew. This is me, a sinner on whom the Lord has turned his gaze."

That has made some headlines because the pope said he was a sinner. It's part of the gentler idea of the church's role he posited in the interview, a stance in contrast to the pretty fearsome growls his two predecessors turned on the world.

It's also remarkable because Caravaggio has become a painterly symbol of things countercultural. Not only was he probably bisexual, a killer, who consorted with, slept with and used whores as models. He went against everything the conservatives of his time agreed made painting beautiful and worthy of display in churches to inspire the faithful. (I imagine Ratzinger never made a special stop at The Deposition of Christ in the Vatican Museum. I did, as you can see, and it's amazing.)

So what was important in its day about The Calling of Saint Matthew? Here Caravaggio thinks about it in my novel A NAME IN BLOOD:

Scipione was talking about St Matthew. It was nothing Caravaggio hadn’t heard again and again in the five years since he painted it. The sensation around his style in Matthew had yet to subside. He had endured many expositions from connoisseurs on the originality with which he shrouded Our Saviour in the gloom of a basement and, in doing so, illuminated him more lustrously than all the expensive ultramarine blue on a conventional painter’s palette could have done. He had suffered just as many curses and as much haughty derision, too.

But none saw it as Caravaggio did. They all thought the light fell on the grey-bearded figure at the table, that this was Matthew the tax collector, turning his finger towards himself as if to ask whether Christ called to him.

They had the wrong man. The finger pointed beyond the bearded fellow to a youth with his head lowered over the dark tabletop. He shuffled his coins, sullen and dissatisfied with his career. Most of those who saw the painting looked upon this young man as a symbol of the miserable life Matthew was about to leave behind him. But all the other figures on the canvas were content that there should be nothing more in their world than a melancholy counting-house. That despondent young man at the end of the table saw the world through a veil of unfulfilment. He was the one waiting to be called.

Caravaggio had painted the saint in the moment before he raised his head to see the darkness lift. It had been so for me, he thought. These paintings were the extended hand of Christ to his art, calling him on to his vocation. He was still following it, wondering where it would lead – just as Matthew wasn’t saved when Christ called him; the saint had to wait years, work hard at his faith and keep the light in his sight. Until his martyrdom.

Published on September 23, 2013 06:43

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, covers, crime-fiction, food, historical-fiction, italy, papal-history, pope-francis, rome

September 16, 2013

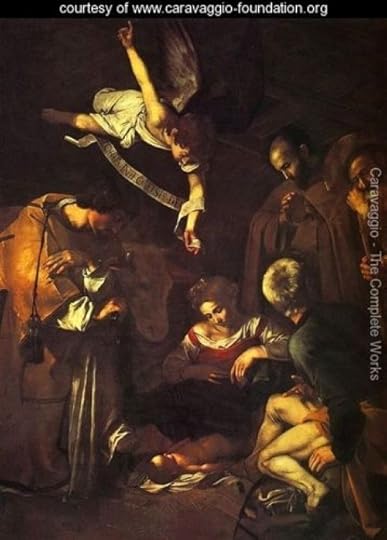

Daily Caravaggio: Nativity with Saints Francis and Lawrence

On the run Caravaggio painted a work that's now on FBI Most Wanted list

Caravaggio's Nativity with St Francis and St. Lawrence is one of the FBI's Top 10 Most Wanted works of art. It was stolen from a church in Palermo in 1969, probably by the Mafia. Various mafiosi have since then claimed it was destroyed before it could be sold to private collectors. Well, they would, wouldn't they.

In some ways, the painting was linked to crime from the moment of its creation. Caravaggio had fled to Sicily from Malta because of a fight with a knight. (He had fled to Malta from Rome, because he killed a pimp.)

To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel.

Here Caravaggio awakes in the studio where he's painting the Nativity. Haunted, pursued, and fearful:

Caravaggio's Nativity with St Francis and St. Lawrence is one of the FBI's Top 10 Most Wanted works of art. It was stolen from a church in Palermo in 1969, probably by the Mafia. Various mafiosi have since then claimed it was destroyed before it could be sold to private collectors. Well, they would, wouldn't they.

In some ways, the painting was linked to crime from the moment of its creation. Caravaggio had fled to Sicily from Malta because of a fight with a knight. (He had fled to Malta from Rome, because he killed a pimp.)

To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel.

Here Caravaggio awakes in the studio where he's painting the Nativity. Haunted, pursued, and fearful:

In the dawn, he was alone. The outlines of his few belongings, the easel he had built on arrival in Palermo, the glimmer of the early light on the tacks attaching his canvas to its frame – this was all the life left to him now. The sun illuminated these objects, but no companion watched it fall across his face.

He lay on his front, fully dressed and with his arms outstretched, like a man who had been assaulted by an attacker approaching unseen from behind. In the heat of the summer, he sweated through the nights, clothed and armed for a quick getaway in case his murderer should come. Shapes moved in the shadows and he tracked them, holding his breath. The shutters creaked as the wood expanded in the heat of the first sunshine. Their every click and rasp made his heart thrash.

Perhaps his killers would come today. I’d almost welcome the company.

He imagined the saints in the dawn of the day of their martyrdom. They had consolations unknown to him. They were certain of the fate of their souls. But when he pictured their deaths, he saw the bodies they left behind. Slaughtered, bloodless meat.

He leaned over his tray of pigments. ‘Good morning, my only friends,’ he murmured. The clay dug near Siena, filled with iron and making a yellow-brown oil, or burned in a furnace for the red-brown he loved to use; red ochre also from the Tuscan hills, and St John’s White, made from quicklime by Florentine monks; green earth quarried near Verona; and the most expensive, ultramarine blue, ground from lapis lazuli that was mined in the land of the Khans beyond Persia – he touched them all. They were like a cooling salve on a wound.

He descended the stairs to the kitchen. An old Franciscan monk laid a bowl of thin cabbage soup before him. ‘How’s our Nativity progressing, Maestro Michele?’

‘Almost done.’ Caravaggio had finished the canvas two days before. He lingered over it, fearful of what he might encounter if he were to leave his studio.

‘God bless you, Maestro. Where will you go when it’s completed?’

The minced cabbage in the soup was sparse. He noted the skin of a bean floating in the broth, but when he trawled his spoon through the dish he found no trace of the rest of it. ‘I haven’t considered that, Brother Benedetto.’

Only when he was working did he not feel as though he were heading downhill. He tried not to think about the future, because he knew the dangers and hardships he faced. He could hardly explain that to the monk. The Franciscans sought out mortification of the flesh among the poor. For all he knew, Brother Benedetto had skinned the bean and thrown away its meat when he made the soup.

Published on September 16, 2013 01:10

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, covers, crime-fiction, food, historical-fiction, italy, rome

September 9, 2013

Daily Caravaggio: The Denial of St. Peter

Late Caravaggio tells story of a biblical scene with a few gestures

In his later paintings, Caravaggio made himself into a master of suggestion, letting the story of the scene emerge from the darkness in its most telling gestures. The Denial of St. Peter, which is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is the finest example of this shadowed storytelling. In my Caravaggio novel, I have the artist's old patron Cardinal del Monte figuring out the messages behind the gestures.

To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel.

Here's del Monte and Caravaggio in Naples, after the artist has been on the run for years:

In his later paintings, Caravaggio made himself into a master of suggestion, letting the story of the scene emerge from the darkness in its most telling gestures. The Denial of St. Peter, which is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is the finest example of this shadowed storytelling. In my Caravaggio novel, I have the artist's old patron Cardinal del Monte figuring out the messages behind the gestures.

To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel.

Here's del Monte and Caravaggio in Naples, after the artist has been on the run for years:

They went back to the Stigliano Palace. In the studio, Caravaggio pulled away the cloth that covered a painting of a bald, bearded man, a woman and a soldier. The man turned his hands to his chest and pulled in his chin, denying some accusation. ‘St Peter.’

Del Monte went close to the canvas. He glanced sidelong at Caravaggio. The man makes so many bad decisions, he thought. How can he produce such judicious art, such insight into the way people are, and yet not be a saint? ‘It’s so immediate, Michele.’ He let his hands follow the lines of the brush like a musician conducting an ensemble. ‘Peter almost looks as you might, when you’re an old man.’

‘I hope to live so long.’

Michele gave his own face to Peter at the moment of his guilty denial of Christ, del Monte thought. The saint pointed at his heart to show sincerity, but it was the lying manoeuvre of a desperate man. In his expression, del Monte saw that he was guilt-ridden. His eyes didn’t quite rest on the face of the soldier interrogating him. They were distant, looking over the soldier’s shoulder.

Del Monte turned to Caravaggio in surprise. He’s ashamed of himself. ‘St Peter overcame his guilt. Remember that, Michele. He went to found the Church in Rome.’

‘Where he met his death.’

In the dark studio, Caravaggio’s face was shadowed. His wounds marked him as an insulted man. They glinted like silver highlights on black cloth.

Published on September 09, 2013 03:47

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, covers, crime-fiction, food, historical-fiction, italy, rome

September 3, 2013

Daily Caravaggio: Martha and Mary Magdalene

Caravaggio's Detroit masterwork shows use of mirrors, contrasting light

After I posted David with the Head of Goliath, a reader commented on the amazing perspectival detail in David's projecting arm. That's why I'm posting this one of Caravaggio's works today. The convex mirror has been taken to suggest his use of visual aids in formulating perspective in his canvases. David Hockney has written about this in relation to a number of great artists of the period. Caravaggio is a prime candidate because of his dark backgrounds and highly illuminated central figures.

If you put someone under a bright light in a moderately dark room, and then you go inside a camera obscura, the contrast between light and dark will be exaggerated and the scene will look exactly like a Caravaggio painting.

This is Martha and Mary Magdalene. It's at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Which proves that people shouldn't write off the Queen of the Great Lakes, even if the city can't repay its $18.5 billion in debt and recently went into Chapter 9 bankruptcy.

In addition to the suggestion of Caravaggio's technical accomplishments, the mirror symbolises the vanity of Mary's naughty ways, which Martha is persuading her to give up.

To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel.

Here Caravaggio is setting up for a work session, positioning the model and entering the booth he uses as a camera obscura:

After I posted David with the Head of Goliath, a reader commented on the amazing perspectival detail in David's projecting arm. That's why I'm posting this one of Caravaggio's works today. The convex mirror has been taken to suggest his use of visual aids in formulating perspective in his canvases. David Hockney has written about this in relation to a number of great artists of the period. Caravaggio is a prime candidate because of his dark backgrounds and highly illuminated central figures.

If you put someone under a bright light in a moderately dark room, and then you go inside a camera obscura, the contrast between light and dark will be exaggerated and the scene will look exactly like a Caravaggio painting.

This is Martha and Mary Magdalene. It's at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Which proves that people shouldn't write off the Queen of the Great Lakes, even if the city can't repay its $18.5 billion in debt and recently went into Chapter 9 bankruptcy.

In addition to the suggestion of Caravaggio's technical accomplishments, the mirror symbolises the vanity of Mary's naughty ways, which Martha is persuading her to give up.

To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel.

Here Caravaggio is setting up for a work session, positioning the model and entering the booth he uses as a camera obscura:

He laughed as he arranged the earth-brown cloth across her back, folding it over her extended arm and spreading it across the table. ‘Now, see here? Where my hand is, focus there.’

She held her neck still, angled upwards. He went through the curtain, tying it behind him to leave only a small, round gap at head height.

Through that space, the bright light falling on Prudenza showed clearly in the mirror set behind Caravaggio. The mirror projected an image of the girl onto the canvas, a technique he had learned from the men of science at del Monte’s palace. He marked in the key points of her features quickly, tracing them from the projection, so that he could set her precisely in place at the next sitting. He turned his brush around, holding it with the bristles towards him, and carved through the underpaint with the end of the handle. In single strokes, he cut into the ground layer the outline of her ear, her forehead, her jaw and her hands. He would fill in the details later, knowing that the shape and the perspective would be natural, just as seen in a looking glass.

‘Why do you need a mirror in there?’ she called.

‘It makes my job simpler. It allows me to concentrate on what’s really important.’

The mirror couldn’t account for the genius with which he animated a face in pain or devotion, but it set those emotions on a replica of reality so exact that viewers marvelled at his virtuosity. Few asked how he did it – except for del Monte’s scientists, who already knew. Others assumed it was pure mystery, like a Virgin standing on a cloud at the top of an altarpiece.

Prudenza opened her mouth to ask another question, but he hissed for her to be quiet. The mirror was a secret he didn’t wish to share, and not only because he wanted to preserve his technical advantage over other artists. He was wary of the Inquisition. Projecting images was heretical magic.

Published on September 03, 2013 22:28

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, covers, crime-fiction, food, historical-fiction, italy, rome

September 2, 2013

Daily Caravaggio: David with the Head of Goliath

Costanza Colonna and this final canvas key to Caravaggio's mysterious disappearance

The Marchesa of Caravaggio's hometown was an important figure in his life. Costanza Colonna knew him as a small boy and helped him in his career -- and out of jams -- throughout his life. He was living in her cousin's house in Naples when he disappeared in 1610. She too was there. I decided to put this relationship at the center of my novel A Name in Blood, because it takes the traditional story of Caravaggio the bloodthirsty he-man (albeit a gay one) and introduces a connection to the feminine world of creativity and sensitivity. (It takes the most cursory of examinations of his works to see that this was the place he truly inhabited.)

He painted this David with the Head of Goliath right before his disappearance and presumed death. It's now at the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

It plays a central role in the denouement of my novel, as does Caravaggio's relationship with Costanza Colonna.

To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel.

Goliath's face in this picture is generally acknowledged to have Caravaggio's features. I think there's an even more sinister and yet more beautiful connection than that. Here Costanza has taken a look at the unfinished David with the Head of Goliath:

The Marchesa of Caravaggio's hometown was an important figure in his life. Costanza Colonna knew him as a small boy and helped him in his career -- and out of jams -- throughout his life. He was living in her cousin's house in Naples when he disappeared in 1610. She too was there. I decided to put this relationship at the center of my novel A Name in Blood, because it takes the traditional story of Caravaggio the bloodthirsty he-man (albeit a gay one) and introduces a connection to the feminine world of creativity and sensitivity. (It takes the most cursory of examinations of his works to see that this was the place he truly inhabited.)

He painted this David with the Head of Goliath right before his disappearance and presumed death. It's now at the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

It plays a central role in the denouement of my novel, as does Caravaggio's relationship with Costanza Colonna.

To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel.

Goliath's face in this picture is generally acknowledged to have Caravaggio's features. I think there's an even more sinister and yet more beautiful connection than that. Here Costanza has taken a look at the unfinished David with the Head of Goliath:

‘It’s David with the Head of Goliath, is it not, Michele?’ she said.

Caravaggio went on with his work. ‘Quite so, my lady.’

She had seen many Davids before, but never one like this. David was usually a triumphant figure, the helmeted warrior of old Maestro Donatello or the muscular giant by the divine Michelangelo which she had seen in a square in Florence. ‘The way you’ve painted it, David looks so sad.’

Costanza tried to remember how Caravaggio had appeared as a child. There’s more than a trace in the painting, she thought, of the boy I took in so many years ago. ‘Is it you, Michele?’

He rounded on her. She stepped away in surprise. The wound on his cheek, the twitching eye, the lowered shoulders, his scars all threatened her.

‘The boy looks like you used to.’ She gestured towards the canvas with a quivering finger.

‘You’re mistaken, my lady.’

Published on September 02, 2013 03:38

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, covers, crime-fiction, food, historical-fiction, italy, rome

August 30, 2013

Daily Caravaggio: St. John

Caravaggio's St. John may have been one of his last works

Caravaggio painted John the Baptist many times. The last one (which was probably this, now housed at the Galleria Borghese in Rome) was probably intended as part of a package of paintings that would buy his pardon from the Pope (by ingratiating him with Scipione, the powerful papal nephew). He had been four years under sentence of death and on the run. To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel. Near the end of the book, Caravaggio is working on the painting when an Inquisitor with whom he has previously jousted surprises him:

Caravaggio painted John the Baptist many times. The last one (which was probably this, now housed at the Galleria Borghese in Rome) was probably intended as part of a package of paintings that would buy his pardon from the Pope (by ingratiating him with Scipione, the powerful papal nephew). He had been four years under sentence of death and on the run. To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book this month along with a snippet from the novel. Near the end of the book, Caravaggio is working on the painting when an Inquisitor with whom he has previously jousted surprises him:

The Baptist’s plump foot rested on the log at the fringe of the canvas. Caravaggio edged the toes with a deep umber, filling the nails with grime. He stepped back from the painting, the first of the works he would take to Rome for Cardinal Scipione. The young St John reclined on a stump, his fleshy midriff twisting against his staff and a flowing red drapery. Beside him, the ram that was the symbol of the saint reached up to eat a leaf from a tree.

‘He’s a bit chubby for an ascetic who lived off locusts in the desert, don’t you think?’

Caravaggio dropped his palette and brush. Spinning towards the stairs beyond the studio door, he unsheathed his dagger.

‘A fat little saint. It’s almost conventional. Back in Rome everyone’s doing dirty toenails now, just like you. I couldn’t even call that a typical touch of Caravaggio anymore.’ Leonetto della Corbara grinned as he approached the canvas. Guiding the dagger back to its sheath, he embraced Caravaggio. He held on as the artist pulled away. ‘But I imagine the painters who copy your style in Rome wouldn’t be quite so poised to drop their work and take up their weapon.’

‘Yes, I’m the real thing.’

Published on August 30, 2013 03:02

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, covers, crime-fiction, food, historical-fiction, italy, rome

August 29, 2013

Daily Caravaggio: The Flagellation

Caravaggio's depiction of torture reflects his own fear of execution

For the last four years of his life, Caravaggio was on the run under sentence of death. He became much obsessed with execution. It gave depictions of the deaths of saints and, in particular, of the torment of Christ a deep resonance for him--and for those of us lucky enough to see his paintings. To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book each day this month along with a snippet from the novel. The Flagellation is in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples. You approach it through a series of other galleries whose doors line up with this astonishing image, so that it's truly inescapable. Unlike the other masterworks in the Capodimonte, Caravaggio's Flagellation has a room of its own, windowless and dark, like the dungeon where Jesus is tortured. Caravaggio spent a long time on the painting by his standards, and there's evidence of his revising it considerably, painting out a couple of figures, widening the canvas. Here's the point in A Name in Blood where Caravaggio finally gets it right:

For the last four years of his life, Caravaggio was on the run under sentence of death. He became much obsessed with execution. It gave depictions of the deaths of saints and, in particular, of the torment of Christ a deep resonance for him--and for those of us lucky enough to see his paintings. To coincide with the UK paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book each day this month along with a snippet from the novel. The Flagellation is in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte in Naples. You approach it through a series of other galleries whose doors line up with this astonishing image, so that it's truly inescapable. Unlike the other masterworks in the Capodimonte, Caravaggio's Flagellation has a room of its own, windowless and dark, like the dungeon where Jesus is tortured. Caravaggio spent a long time on the painting by his standards, and there's evidence of his revising it considerably, painting out a couple of figures, widening the canvas. Here's the point in A Name in Blood where Caravaggio finally gets it right:

In the last light of the afternoon, he sat on a stool in his studio, slugging wine from a flask. There were still many touches he would need to make, but he had it now. The Flagellation was awash with cruelty and pain. It stank like a killing in a backstreet. He stared at the malicious pleasure on the face of the man at Jesus’s shoulder. He wondered if this was what people saw on his own face when rage overcame him. The thought shamed him.

Published on August 29, 2013 03:42

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, covers, crime-fiction, food, historical-fiction, italy, rome

August 27, 2013

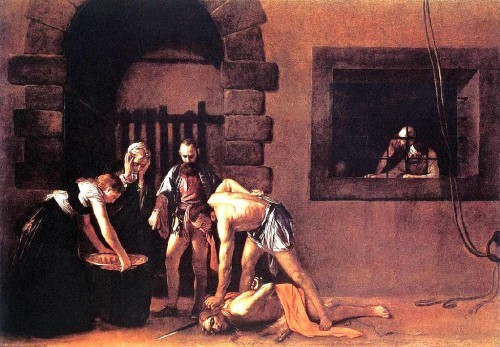

Daily Caravaggio: The Beheading of St. John the Baptist

Caravaggio's Malta masterwork depicts the death as a scene in motion

Few of Caravaggio's paintings remain in the location for which he painted them. A marvellous exception is The Beheading of St. John the Baptist. It's still in the oratory of the Co-Cathedral of St. John in Valletta, Malta. It was intended to be a point of meditation for the Knights of Malta, who received their instruction beneath it as young men and for whom sacrifice at the point of a sword was not unlikely. During the many hours I spent before the painting, I realized Caravaggio had captured the moment of the saint's death--but also the moments before and after. He changed his technique, made his strokes faster and less polished, so that we'd recognize the tableau as part of a story in motion. To coincide with the paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book each day this month along with a snippet from the novel. In A Name in Blood, a leading Knight of Malta takes Caravaggio to the Oratory and tells him what he must paint there:

Few of Caravaggio's paintings remain in the location for which he painted them. A marvellous exception is The Beheading of St. John the Baptist. It's still in the oratory of the Co-Cathedral of St. John in Valletta, Malta. It was intended to be a point of meditation for the Knights of Malta, who received their instruction beneath it as young men and for whom sacrifice at the point of a sword was not unlikely. During the many hours I spent before the painting, I realized Caravaggio had captured the moment of the saint's death--but also the moments before and after. He changed his technique, made his strokes faster and less polished, so that we'd recognize the tableau as part of a story in motion. To coincide with the paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book each day this month along with a snippet from the novel. In A Name in Blood, a leading Knight of Malta takes Caravaggio to the Oratory and tells him what he must paint there:

‘It’s dark in here,' Caravaggio said.

‘You’ve painted in churches before. They’re all dark.’

‘These windows are so high and narrow. The place is like a dungeon.’

‘How does the Bible describe St John’s death? “The king sent a soldier of the guard and gave orders to bring John’s head to him. He went and beheaded him in the prison and brought his head on a platter.’ Martelli put his hand to Caravaggio’s shoulder. ‘The Baptist was decapitated in a dungeon. So paint a dungeon for our dungeon here.’

Published on August 27, 2013 03:42

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, covers, crime-fiction, food, historical-fiction, italy, rome

August 18, 2013

International Crime Fiction Blog interview

Scene of the Crime highlights Matt

Scene of the Crime highlights MattThe terrific international crime fiction blog Scene of the Crime features an interview with me entitled "Tough work but somebody's got to do it." That's a reference to the Italian locations and research for the thriller I'm writing right now. The interview looks at my original Palestinian crime novels, but I also talk about how I got the idea for my more recent historical crime fiction about Mozart and Caravaggio. The great J. Sydney Jones (check out his absorbing historical crime fiction) runs the blog and introduces the piece thus:

It is a real pleasure to have Matt Rees back on Scene of the Crime. He was one of the first writers I had on the site, three-and-a-half years ago. Matt is the old-fashioned man of letters type: former Middle East correspondent for The Scotsman and Newsweek, he was Time’s Jerusalem bureau chief during the Palestinian intifada. Read more.

Daily Caravaggio: Seven Acts of Mercy

Caravaggio's Naples masterpiece

The great Italian artist Caravaggio painted The Seven Works of Mercy (or Our Lady of Mercy, as it's actually called) in Naples in 1607. He was on the run with a price on his head. He was, of course, the perfect character for a historical thriller, because he was producing masterpieces while trying to keep a step ahead of the men who wanted him dead. To coincide with the paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book each day this month along with a snippet from the novel. The church where the painting is housed is on a very busy street the medieval district. The street noise is very much part of the painting, which shows a crowded Naples scene. I imagined Caravaggio right there:

The great Italian artist Caravaggio painted The Seven Works of Mercy (or Our Lady of Mercy, as it's actually called) in Naples in 1607. He was on the run with a price on his head. He was, of course, the perfect character for a historical thriller, because he was producing masterpieces while trying to keep a step ahead of the men who wanted him dead. To coincide with the paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book each day this month along with a snippet from the novel. The church where the painting is housed is on a very busy street the medieval district. The street noise is very much part of the painting, which shows a crowded Naples scene. I imagined Caravaggio right there:

The great Italian artist Caravaggio painted The Seven Works of Mercy (or Our Lady of Mercy, as it's actually called) in Naples in 1607. He was on the run with a price on his head. He was, of course, the perfect character for a historical thriller, because he was producing masterpieces while trying to keep a step ahead of the men who wanted him dead. To coincide with the paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book each day this month along with a snippet from the novel. The church where the painting is housed is on a very busy street the medieval district. The street noise is very much part of the painting, which shows a crowded Naples scene. I imagined Caravaggio right there:

The great Italian artist Caravaggio painted The Seven Works of Mercy (or Our Lady of Mercy, as it's actually called) in Naples in 1607. He was on the run with a price on his head. He was, of course, the perfect character for a historical thriller, because he was producing masterpieces while trying to keep a step ahead of the men who wanted him dead. To coincide with the paperback publication of my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm posting each of the paintings that appear in the book each day this month along with a snippet from the novel. The church where the painting is housed is on a very busy street the medieval district. The street noise is very much part of the painting, which shows a crowded Naples scene. I imagined Caravaggio right there:

Outside the taverns, Neapolitans lifted long handfuls of maccheroni and lowered it into their mouths, their heads cast back as if they might feed it directly through their throats and into their stomachs like sword swallowers. The wailing of the zampogna cut through the noise of the crowd, a shrill melody and a low bagpipe drone that reverberated in his very ribcage.

He slipped into a pew before the altar of the Pio Monte. Lena gazed on him with compassion. She was Our Lady of Mercy, the Virgin he had painted surveying the crowded streets of Naples.

Published on August 18, 2013 03:34

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, covers, crime-fiction, food, historical-fiction, italy, rome