Matt Rees's Blog, page 8

March 17, 2013

Meet Nutanyahu: New ebook shows why Israeli PM wants to fail

The new ebook from my alternative news venture DeltaFourth. It draws on many meetings with Bibi over a decade and a half, and comes to very unconventional conclusions.

PSYCHOBIBI: Who is Israel’s Prime Minister and Why Does He Want to Fail?

The shocking, hilarious, innovative new ebook from D4.

Benjamin Netanyahu, the man often portrayed as an extremist, is really just locked in a deep psychological battle with the ghosts of his tough father and golden brother. The result: Bibi’s driven to succeed, so long as he can always get it wrong in the end. Confused? You won’t be. Not after you’ve met Psychobibi. Hard-hitting and irreverent, incisive and hardboiled, D4 eviscerates the myth behind the man they love to hate.

Special $2.99 price on amazon.com, or the equivalent in your local currency.

Published on March 17, 2013 00:48

•

Tags:

bibi, biography, middle-east, netanyahu, politics, psychobibi, psychology

February 6, 2013

Podcast: Journalism's Special Forces

My latest podcast is about my new alternative news project DeltaFourth. I read from THE MURDER OF YASSER ARAFAT, the first explosive ebook from DeltaFourth. The ebook reveals how Yasser Arafat was murdered by people in his inner circle. It's the prototype for DeltaFourth's forthcoming series of long-form journalistic ebooks -- stunning breaking news written in a hard-boiled novelistic style that responds to the excitement of the events it describes.

Download the Podcast: (Download the MP3)

Subscribe via iTunes

Download the Podcast: (Download the MP3)

Subscribe via iTunes

Published on February 06, 2013 10:27

•

Tags:

journalism, middle-east, palestinians, podcast, yasser-arafat

Secret Mossad Hit List Revealed

My partner at new alternative news venture DeltaFourth Matthew Kalman wrote on The Times of Israel about our ebook

The Murder of Yasser Arafat

, in which we show that a senior Palestinian from the leader’s inner circle poisoned him. One of The Times’ other columnists responded with a piece in which he said Arafat was offed by the Israeli Mossad.

My partner at new alternative news venture DeltaFourth Matthew Kalman wrote on The Times of Israel about our ebook

The Murder of Yasser Arafat

, in which we show that a senior Palestinian from the leader’s inner circle poisoned him. One of The Times’ other columnists responded with a piece in which he said Arafat was offed by the Israeli Mossad.The Israelis may – or may not – have provided the polonium used to wax Arafat. But they didn’t put it in his tea. That, we discovered, was left to one of his close advisers.

Still the Mossad is thought of as pretty much having a finger in every nasty pie, by everyone from Palestinian coffee vendors to British newspapermen to thriller writers the world over. So here it can be revealed for the first time, the tally of secret Mossad hits:

The Mossad killed Monty Python’s Graham Chapman. But it didn’t kill Yasser Arafat.

The Mossad killed Michael Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Roger Rabbit. But it didn’t kill Yasser Arafat.

The Mossad killed Che Guevara, JFK, Lee Harvey Oswald and Reinhard Heydrich. But it didn’t kill Yasser Arafat.

It assassinated Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi, and King Xerxes I of Persia. But it didn’t kill Yasser Arafat.

The Mossad killed Meir Kahane, Aldo Moro, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and Vlad Dracula. But it didn’t kill Yasser Arafat.

It joined forces with video to kill the Radio Star. But it didn’t kill Yasser Arafat.

The Mossad killed Snorri Sturluson, Lord Mountbatten, and Vlad Dracula again, this time for good with a silver bullet. But it didn’t kill Yasser Arafat.

It killed Olof Palme, Jill Dando, and Dick Cheney (though having used its silver bullet on Dracula that one didn’t stick.) But it didn’t kill Arafat.

The Mossad killed Thomas a Beckett, Simon Bocanegra, and Old Hamlet. But it didn’t…

There are more, but they're far too dangerous to name. Naturally DeltaFourth will be delighted to hear if there are others you think we’ve missed.

Published on February 06, 2013 10:26

•

Tags:

assassinations, israel, israelis, middle-east, mossad, palestine, palestinians

January 24, 2013

'Orwell Brigade' takes on abuse of power

One of my essays is included in a new collection by crime writers called "The Orwell Brigade." The idea is that authors -- in particular crime writers -- spend their time considering the very same questions as George Orwell did in his novels and essays about power. The Orwell Brigade is the brainchild of Christopher G. Moore (check out his excellent Vincent Calvino mysteries, set in Thailand, where CGM lives). He enlisted me and a dozen other authors, including Barbara Nadel, Quentin Bates, John Burdett and Colin Cotterill. As he puts it, the aim is "to reclaim the role of telling truth to authority, to examine abuse of power, and to question the false histories and narratives officials use to justify their decisions and policies. The traditional media have retreated to the safety of entertainment and gossip to turn a profit. We have paid a high price for that retreat." It's a terrific read. My essay is called Doublethink for the Arab Spring.

One of my essays is included in a new collection by crime writers called "The Orwell Brigade." The idea is that authors -- in particular crime writers -- spend their time considering the very same questions as George Orwell did in his novels and essays about power. The Orwell Brigade is the brainchild of Christopher G. Moore (check out his excellent Vincent Calvino mysteries, set in Thailand, where CGM lives). He enlisted me and a dozen other authors, including Barbara Nadel, Quentin Bates, John Burdett and Colin Cotterill. As he puts it, the aim is "to reclaim the role of telling truth to authority, to examine abuse of power, and to question the false histories and narratives officials use to justify their decisions and policies. The traditional media have retreated to the safety of entertainment and gossip to turn a profit. We have paid a high price for that retreat." It's a terrific read. My essay is called Doublethink for the Arab Spring.

Published on January 24, 2013 04:00

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, essays, george-orwell, politics

January 11, 2013

What's D4? My new alternative news venture reshapes journalism

Journalists know that their readership is changing. The primary approach to this change has been, frankly, to panic. And of course to fire people. To offer the same style and content, but with links to Twitter feeds and Facebook pages. I've come to the conclusion that these things don't help. What readers want is a different style of journalism.

Journalists know that their readership is changing. The primary approach to this change has been, frankly, to panic. And of course to fire people. To offer the same style and content, but with links to Twitter feeds and Facebook pages. I've come to the conclusion that these things don't help. What readers want is a different style of journalism.With my new alternative news venture DeltaFourth, I've written a long piece in the style of a novel. I aimed to make the actual writing respond to the excitement and the revelations of the content. In this case, it's called The Murder of Yasser Arafat. So I wanted to make it read like a thriller.

That idea is anathema to many traditional journalists. The notion of objective journalism, particularly in the U.S., is to take something exciting and report "just the facts." Ah, but facts are so dull. Try this: Yasser Arafat was murdered. Kind of interesting, makes you want to know how, but also makes you think "Oh, so that's all there is to it." Doesn't make you think: "Wow, how did that happen and who did it?" Read my piece and you'll keep going to the end because of the style I brought to it from my fictional crime writing.

I came to this conclusion with my pal Matthew Kalman. Between us we have almost 60 years of journalism experience. We've always been trying to make our journalism more exciting and readable. But we often find that there's a fat guy or an argumentative lady in New York or London (known as an editor) determined to make it as bland as possible. By publishing our own work through our own company for download, we eliminated the fat guy and the argumentative lady.

It's also a generational shift in the attitude to writing. I spoke to some teenage schoolkids recently. One of them has written a sci-fi novel and was intrigued to know about the new validity of "self-publishing" online. By publishing her work (once it's ready), I expect she'll bring young people to reading a literature of their own by one of their own that will later translate into reading of other works.

I hope you'll enjoy DeltaFourth as we produce more pieces. We'll have one soon (about the time of the Israeli election) about Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and why he really wants to be a failed prime minister....

Published on January 11, 2013 22:32

•

Tags:

blogging, deltafourth, journalism, middle-east, online-writing, palestine, social-media, writing, yasser-arafat

December 23, 2012

Free Short Story for a Scary Xmas

My Christmas present to you: a free short story to send shivers down your spine when everyone else is pretending to be happy. The Man Who Went Out at Night is a supernatural short story set in the Welsh mining town where my Dad grew up and where I spent much of my childhood. In the valley, the people stay in their houses by night, terrified of the one figure who ventures out in the dark: The Man Who Went Out at Night. Drawn from his home to sleep with an older woman, Tommy Williams confronts The Man. The meeting leads to murder and a grisly conclusion. But perhaps it also gives Tommy a chance to be free of the fear felt by the people of the valley. It's free on amazon from Monday through Friday this week.Download the U.S. version free to your Kindle or (even if you don't have an ereader) download it to your computer.

Published on December 23, 2012 04:45

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, free-books, free-story, freebie, short-story, supernatural, wales

November 25, 2012

Review to win free 'Mozart's Last Aria'

Write a review of one of my books on amazon.com or amazon.co.uk and get a chance to win a free copy of my novel Mozart's Last Aria.

Write a review of one of my books on amazon.com or amazon.co.uk and get a chance to win a free copy of my novel Mozart's Last Aria. Just write your review, send me the link to the review at mattreesbooks@gmail.com, and you'll be entered in a drawing for a free, signed copy of the book. I'll be doing the drawing on Dec. 5, the 221st anniversary of Mozart's death -- which is of course the starting point for the mystery in Mozart's Last Aria.

Published on November 25, 2012 09:57

•

Tags:

classical-music, competition, crime-fiction, free-book, historical-novel, mozart, mystery

November 14, 2012

Podcast: The Sweetest Things, a short story of the Arab Spring

A short story set in Amman, Jordan, during the Arab Spring. A Western journalist, befriends a wealthy sweet-seller named Said. He grows close to him and his lover, a poor taxi driver, as he covers the anti-government riots of the Arab Spring. He observes the growing conflict between the two men until its shocking conclusion. The story draws on my many years reporting and, for a while, living in the Jordanian capital, which finds itself at the seething center of the Mideast’s many conflicts.

Download the Podcast: (Download the MP3)

Subscribe via iTunes

Published on November 14, 2012 03:11

•

Tags:

arab-spring, free-story, middle-east, reading, short-story

November 12, 2012

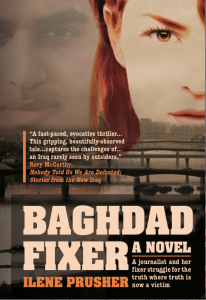

The Iraq war novel we've been awaiting

On the whole, it’d better if there was no war. But war has given us some of the great novels of all time. Until now, the Iraq war has been written about mainly in macho with-the-troops memoirs by embedded journalists, dry-as-dust nonfiction, and bile-licious invective. Unless you’re macho, dry, or hateful, none of these are particularly fulfilling reading options. With “Baghdad Fixer,” we have the novel of the Iraq war we’ve been waiting for. Writer Ilene Prusher, who publishes “Baghdad Fixer” this week, has been a foreign correspondent around the Middle East and Asia for two decades, including on the ground in Iraq. Her novel is narrated by a foreign journalist’s 'fixer' – the person who translates and often sets up interviews – who is an Arab man named Nabil. The book centers around his relationship and understanding of his beautiful, mercurial boss, a female reporter from the U.S. named Samara. It takes them into the nasty underside of the Iraq conflict – and into danger. Before she embarked on a book tour of the UK, Ilene took time to answer some questions about how she wrote the book.

On the whole, it’d better if there was no war. But war has given us some of the great novels of all time. Until now, the Iraq war has been written about mainly in macho with-the-troops memoirs by embedded journalists, dry-as-dust nonfiction, and bile-licious invective. Unless you’re macho, dry, or hateful, none of these are particularly fulfilling reading options. With “Baghdad Fixer,” we have the novel of the Iraq war we’ve been waiting for. Writer Ilene Prusher, who publishes “Baghdad Fixer” this week, has been a foreign correspondent around the Middle East and Asia for two decades, including on the ground in Iraq. Her novel is narrated by a foreign journalist’s 'fixer' – the person who translates and often sets up interviews – who is an Arab man named Nabil. The book centers around his relationship and understanding of his beautiful, mercurial boss, a female reporter from the U.S. named Samara. It takes them into the nasty underside of the Iraq conflict – and into danger. Before she embarked on a book tour of the UK, Ilene took time to answer some questions about how she wrote the book.The book's dedicated to "the Fixer who told me this story." Tell us about that?

The capital F plays off on something Nabil says at the end of the book. In Islam, God has 99 names, and Nabil muses, “I should like to create the hundredth: the Fixer.” So the dedication is a reference to Nabil’s spirituality, and to my own personal experience that when my writing is on a roll, when the story is just flowing out of me, it’s somehow bigger than me and there’s a divine inspiration in it.

You're a journalist.

Why did you write a novel, rather than a work of nonfiction?

Writing a novel was the only way I could step out of my journalistic shoes and truly enter into the world of my characters, or into what one of my teachers – quoting the American writer John Gardner – called the “fiction dream.” For years as a journalist, I’d interview people but feel that it wasn’t quite enough. I wanted to do more than spend an hour or two or three with them, and then move on. Once I was walking in Nabil’s shoes, I really felt I could see his Baghdad, and to see how Sam would look through his eyes. Although I still love journalism, for the past decade I’ve found myself tired of reading journalists’ books – and nonfiction in general - and increasingly drawn to fiction. I choose to tell the whole story from the fixer’s perspective, because if the foreign journalist had been the narrator, she’d have been too close to home and I wouldn’t have felt free to truly enter that fiction dream.

What do you see as the difference between writing this as fiction, as opposed to nonfiction?

I did experience some but not all of the events in the novel – I was never kidnapped but many of my friends were. Had I written nonfiction, I would need to purely stick to the facts. I became interested in what I only later realized is something that literary people call “allohistory” – imagining a different outcome of history through fictional narrative. What if the intense things I experienced had turned out in a radically different way? Also, I didn’t want be stuck within the confines of writing about Iraq exactly as it is during one particular point in time, but to have Iraq be a rich and fascinating backdrop for looking at how journalists and their “fixers” interact with each other.

Do you think readers will come to it looking for an entertaining story? Or will they expect to be informed about real events in Iraq?

Do you think readers will come to it looking for an entertaining story? Or will they expect to be informed about real events in Iraq?There’s a bit of both, though I hope more of the former. I think a reader should want, as part of the story, to learn something unexpected about Iraq and about the Middle East. But I think the trajectory of the characters’ experience is the most compelling reason to read this book – or nearly any novel. Baghdad Fixer does expose the reader to some of the lunacy that surrounded the US-led invasion or Iraq in 2003. But it’s certainly not a guide to understanding all the nuances of Iraqi politics or the horrors of the post-invasion period, because there are so many other places to go for a factual account of that.

Is all the "real" explanation true? Or did you change events and elements of the Iraq conflict to fit your story?

Most of the “real” explanations are true. Real-life political leaders like George Bush and power-brokers like Muqtada al-Sadr had to figure into the larger backdrop. But, for example, one of the most despicable figures in the book – Technical Ali – is a complete fiction. There were, of course, many real-life forgers and thugs like him. His name was so believable because there was a real-life figure named Chemical Ali, a cousin of Saddam Hussein, who is famous for having gassed thousands of Kurds. He was convicted of crimes against humanity and hanged in 2010.

The title is quite thriller-like and one of the blurbs says it's a thriller. But it's really something quite different, I think. How would you classify it?

I agree; it’s not a classic thriller. I myself have a hard time classifying it, but if I had to, I’d say it could be filed under both historical fiction and contemporary fiction. The Jerusalem Post literary editor wrote that it was “a journey into Iraq’s psyche.” I think that’s more accurate. What makes the story more of a psychological novel is that we’re inside Nabil’s head. He’s a young man who loves the written word, is obsessed with it, so much that he sometimes types in the air when he walks around. He wants to connect through language, to fine-tune his English, to understand Samara’s slang. He has a UK connection – he lived in Birmingham for a while as a child – but the world of America is new to him and he tries to understand it through Samara. But his envy and desire is mixed with disdain, because she represents the occupier. So the book is also a celebration of words – of the challenges and art of translation –– because Nabil is constantly having to play moderator between East and West.

The characters of the journalist and the fixer are very profoundly drawn. How much of you is in the journalist Samara? And was the fixer based on any one person?

Samara doesn’t look like me and act like me, except perhaps in my basest journalistic moments, when all I cared about is the story – not moments I’m necessarily proud of. She’s much more aggressive than I am. Samara’s character was inspired by me and probably 20 other female foreign correspondents I’ve worked with over the years. In fact, I wanted to make Sam like some of the reporters I met, male and female, who were a little arrogant and insensitive, exactly the kind of reporters who seemed likely to exploit their fixers. Apparently I so succeeded in making Sam manipulative – serving the story above all else – that I’ve had several people tell me that they didn’t really like her. But they love Nabil, and to me that’s an achievement. Nabil is similarly part composite, part fiction. He’s a combination of people I’ve worked with in Iraq, Afghanistan, the West Bank and Gaza. After I began writing in his voice for a while, he seemed to be a real person to me. I felt I could conjure him. I would try out walking around the room like him – when no one else was looking – and sometimes asking, okay, what would Nabil do? I’d hear a song and think, “Oh, Nabil would love this song.” And then on several occasions, I cried when I made Nabil or Samara suffer. For a while I thought I was losing my mind. And then I realized no, I’m just writing fiction. These characters are alive now.

Did you experience a lot of the cross-cultural misunderstandings which afflict the journalist and the fixer in the story?

The cultural gaps are at times enormous. Going back to the question of language, I on many occasions worked with people who’d learned all of their English at the local British Council office in Pakistan, for example, and had never stepped foot in a Western country, much less an English-speaking country. Some fixers I worked with were fluent in English, but virtually ignorant of Western culture, which made it uncomfortable at times. For example, I worked with a fixer who kept telling me that he regrettably had to beat his much younger wife, because she kept contradicting him in front of his family. He said this with a flawless Manchester accent and without shame – it didn’t occur to him how outrageous it sounded in my ears. I worked with many fixers over the years – most of them male. I did on occasion, particularly if it was an attractive man, feel a sexual tension, a clash of cultures, a desire on the fixer’s part to know me, to push the boundaries, to “protect” me beyond what I felt was necessary, to know what American women are like. I was once asked by a fixer – in a Muslim country other than Iraq - if I would marry a man who already had a wife. It was a thinly veiled marriage proposal; he had a wife and wanted a second one, which Islam allows. I found this flattering...but I also realized that he had probably been interpreting my friendliness as a sign of my interest in him.

The narrator of the book is an Arab and a man. Was it difficult to enter that head, as it were? You're not an Arab man. What's your background?

I don’t know what was more outrageous on my part – writing as a man, an Iraqi, or as Muslim. I’m an American Jewish woman from the other side of the world. Who am I to write this character? I ask myself that question many times. And yet, writing as Nabil felt like the most natural thing in the world. I have no direct familial ties to Iraq, and yet, there was something that felt familial and familiar to me from the moment I arrived. Jews have a rich history in Iraq, and it seemed to me, in an odd way, that there was something natural about being a Jew in Iraq. And by the time I got to Iraq, I’d already spent a lot of time in the Middle East, had learned some Arabic, felt like I was where I needed to be – if not quite belonged. I didn’t feel entirely foreign in Iraq, odd as it sounds. And because I don’t look foreign in the Arab world, I’ve “passed” on many occasions and been a proverbial fly on the wall. This ultimately made it easier for me to imagine Iraqi characters. Also, I visited with one family many, many times. A member of the family, a woman who is my age, is a lecturer in literature at Mustansirriyah University in Baghdad. We maintain a close long-distance friendship. She read the book in its early stages and gave me important feedback, which helped in “getting” certain things about Iraq. When I was writing, I would play music Nabil likes, close my eyes and imagine his shoes, pretend to feel stubble on my face or a receding hairline, and as time went on, Nabil came to me quite easily.

You write in the present tense. Why did you decide to do that?

It just kept coming out that way. In the present tense, I could feel myself walking in Nabil’s shoes through Baghdad. The present tense carries an immediacy that you can almost taste. It lets the reader walk through Nabil’s life and experience it close up. I took a few chapters of this book to a wonderful summer course at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop a few years ago. My teacher there, Wayne Johnson, explained that this voice I’d chosen – first person, present tense – is powerful in its immediacy, but also challenging. “It collapses the psychic distance,” was how he put it. It’s a bit like “Being John Malkovich.” Today, you’re being Nabil al-Amari. That fascinates me.

Published on November 12, 2012 02:17

•

Tags:

arab, baghdad-fixer, ilene-prusher, interview, middle-east, review, writer, writing-life

October 16, 2012

Podcast: Caravaggio in Sicily, a short story

As an introduction to my Caravaggio novel A NAME IN BLOOD, here's a short story about an incident in the artist's life that was very striking to me, but which didn't fit with the narrative of the novel. In "Lazarus's Brush" Caravaggio flees the men who seek to kill him and arrives in Sicily. He's commissioned to paint the raising of Lazarus. The result teaches him about his fears of the violence that stalks him -- but more than that it represents a profound change in his artistic technique, inspiring him as an artist in the face of desperate circumstances.

Download the Podcast: (Download the MP3)

Subscribe via iTunes

Download the Podcast: (Download the MP3)

Subscribe via iTunes

Published on October 16, 2012 00:47

•

Tags:

art, caravaggio, free-story, italy, podcast, readings, short-story, sicily