Matt Rees's Blog, page 11

June 5, 2012

Me and St. Catherine: Why I Wrote a Novel About Caravaggio

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let go.

On the upper floor of the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in central Madrid, I wandered into a broad room where the masterpieces were arrayed like chocolates in a box. Just as with an assortment of sweets, I knew immediately and innately which one attracted me. I stepped into the arms of Caravaggio’s Saint Catherine of Alexandria. She still hasn’t let go.I was in Madrid on a book tour for the Spanish translation of the first of my Palestinian crime novels. The Thyssen is just across the wide, busy Paseo del Prado from the immense museum of that name. It’s a building with two wings: a traditional classical palace in burnt sienna and pink stone; alongside a block of bright white louvered walls and angled blue-glass rooflights, like an old auto factory transported to a sci-fi future. I had no idea what awaited me inside. No idea that my novel A NAME IN BLOOD, which is published in the UK in a few weeks, would grow out of it.

The Caravaggio works I had previously seen in London and New York had impressed me. I was aware of the conventional summary of the stylistic revolution he wrought: to fill his canvasses with darkness and, with a strategically placed lantern, to bring the central action shining out of the shadows. That technique has been a major influence on filmmakers like Scorsese and almost every professional photographer, which is why Caravaggio’s four-hundred-year-old paintings look so modern. I knew something about his life too, though largely through the weird distortions and art-house tedium of Derek Jarman, having seen the British director’s Caravaggio film in college. As a writer, however, I’ve found a confluence of impressionability and idea lies behind every novel, so that only at one given time can you write a particular novel. A few years previously, I might’ve seen Saint Catherine, considered her for a moment, then moved on, as I had done when I saw Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus in London’s National Gallery. But, for some reason, when I entered her room at the Thyssen and she spoke to me, I was listening.

I stayed in that room a long time. I couldn’t say quite how long. But it was at least an hour. The other paintings held my attention a matter of moments. I can’t remember them. (I’ve had similar experiences when I’ve traveled to see Caravaggio’s art around the world since then. No artist has such a capacity to make everything else in a gallery ignorable as Caravaggio has). In the Thyssen, I recall that the walls were of a beige rough fabric, a little like delicate sackcloth. The ceiling was white. Details as scant as you might retain from love-making. You might forget your mood or the immediate surroundings, but you’d have a clear picture of the way she looked at you or the feel of her hand on the back of your neck. Of Catherine, I remember everything. Even things that weren’t on the canvas.

The eyes of Caravaggio’s saint were possessive, grasping and sensual, clandestine and forbidden. For much of the time I was with her, we were alone. It felt as intimate as the languor after an act of love. There’s a question in that post-coital moment and Catherine asked it of me: Is this the last time? Will I see you again? Do you want to know more about me and where I come from?

Eventually I tried to leave the empty room. In her face I saw a plea. As if she wanted me to know that by leaving I would abandon her to her fate, represented by the spiked wheel on which she leaned (where the saint was tortured, before she was dispatched with the sword whose shaft she fondles.) What’s so compelling (and in his day was controversial) about Caravaggio is that he didn’t expect the saint’s suffering to be enough to keep you on her side. He gave her the sexual magnetism of Fillide Melandroni, the whore he used as his model.

The hold Caravaggio subsequently took on me amounted to what many people would call an obsession. I prefer not to use that term, because it implies a degree of madness and the inability to see when you’re mistaken about something. A writer needs to know when he’s gone wrong. Still, I traveled all over Europe and America to see Caravaggio’s works. I learned to paint with oils, to fight with a rapier. I grew a beard like the one Caravaggio sported just before his death at age 39. I did a few others things that paralleled the artist’s life and which were too intimate, shameful, or mystical to be recounted here. So, go ahead, call it an obsession.

Published on June 05, 2012 02:23

•

Tags:

baroque, caravaggio, historical-crime, historical-novel, renaissance

June 4, 2012

Ignore Colm Toibin: More Writers' Rules

Last week I demonstrated why writers who post their “Rules for Writers” are making a big mistake. I included my own five – well, really six – rules for writers. They were a big success. So I thought of some more.

Last week I demonstrated why writers who post their “Rules for Writers” are making a big mistake. I included my own five – well, really six – rules for writers. They were a big success. So I thought of some more.First a recap of my first six rules:

If asked to provide a list of rules for writers, don’t do it.

If you must (because your agent says it’s good for your name to appear in The Guardian), then try not to be cute.

Reveal no stupid prejudices.

Write rules for writers, rather than rules for people who CAN’T write.

Try to have your rules make sense.

If you can’t write, please don’t write.

You may be wondering how I came to formulate these rules. The answer: from reading rules that were anywhere from daft to offensive to pointless to just plain incomprehensible and which had previously been posited by notable writers including Elmore Leonard, Jonathan Franzen, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman, Richard Ford, and Anne Enright.

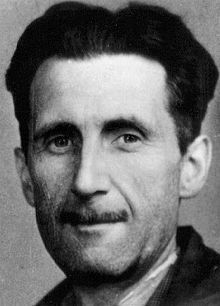

I concluded my post by writing that George Orwell had said it all and there ought to be no further Rules for Writers. Orwell’s last rule, however, suggests that rules are there to be broken. As are statements made on blogs. That’s why I’m adding to my list of rules today.

Rule 7: Don’t be precious.

Helen Dunmore’s rules for writers include “Read Keats’s letters” and “Learn poems by heart.” Perhaps they also should include “Pronounce Rs as Ws” and “Always wear an Ascot while writing.” Thanks to modern educational slackness, no one schooled after the early 1970s can learn a poem by heart without intense effort –– effort that should really be directed toward writing the book.

Rule 8: Don’t be ashamed of earning a living.

Probably you won’t. Earn a living, that is. But if you do, there are plenty of people who’ll suggest you should be ashamed of yourself. You’ve sold out. You must’ve planned your book with “the market” in mind. Geoff Dyer, author of Paris Trance, gives his Rule 1 as “Never worry about the commercial possibilities of a project. That stuff is for agents and editors to fret over.” I suppose you can always marry someone rich. But if you’re intending to write for more than an hour or so a day, you’d better at least consider whether anyone will buy it. For the most part agents and editors will expect you to do the fretting, unless they’ve spent a big chunk of cash on your advance and, therefore, the editor needs to make it pay. In which case, you obviously already considered the commercial possibilities… One of Ian Rankin’s Rules of Writing, I should note, is “Know the market.” Books are sold in shops – well, some of them are – so it’s a product and it has to be sold eventually.

Rule 9: Ignore Colm Toibin’s Rule 5.

The Irish writer says “No alcohol, sex, or drugs while you are writing.” Unless he means “don’t try to type up a chapter while snorting cocaine off a hooker’s ass and sucking champagne through a straw from a flute wedged between her thighs,” I think this is a bad rule. Even then it’d be debatable at best.

Rule 10: Really ignore Toibin’s Rule 5.

It’s a very, very bad rule.

Published on June 04, 2012 02:45

•

Tags:

colm-toibin, geoff-dyer, helen-dunmore, ian-rankin, rules-for-writers, writing

June 3, 2012

A Story of 6 Days Takes 40 Years: Abraham Rabinovich's Writing Life

Machiavelli wrote that "Wars begin when you will, but they do not end when you please." That's certainly true of the Six-Day War of 1967. When fired upon in Jerusalem some months after the passage of those six days, Graham Greene commented that it was perhaps an inaccurate name for the conflict. Indeed the battle that Israel won continues to be waged, sometimes simmering, sometimes seemingly in a deep freeze, but never entirely settled. Which is why Abraham Rabinovich's book,The Battle for Jerusalem: An Unintended Conquest That Echoes Still, first published 40 years ago, is now available in an expanded e-book format. Here he chats about how he researched the book back in the late 1960s and now reissued it.

Machiavelli wrote that "Wars begin when you will, but they do not end when you please." That's certainly true of the Six-Day War of 1967. When fired upon in Jerusalem some months after the passage of those six days, Graham Greene commented that it was perhaps an inaccurate name for the conflict. Indeed the battle that Israel won continues to be waged, sometimes simmering, sometimes seemingly in a deep freeze, but never entirely settled. Which is why Abraham Rabinovich's book,The Battle for Jerusalem: An Unintended Conquest That Echoes Still, first published 40 years ago, is now available in an expanded e-book format. Here he chats about how he researched the book back in the late 1960s and now reissued it.Would you recommend any books on writing?

The best books on writing are well-written books. Anything by Conrad, Naipaul’s ‘A Bend in the River’, Bruce Catton’s ‘A Stillness at Appomatox’.

How did you come to write The Battle for Jerusalem?

How did you come to write The Battle for Jerusalem?I was working at a newspaper on Long Island in May 1967 when things in the Middle East began to heat up. Egypt moved troops into Sinai, Israel mobilized its reserves. It reached a point where war seemed to me inevitable. I drove up from New York to the country on a Sunday and spent an hour walking back and forth on a dirt road to think out my options. I had been in Israel once before, in 1956, and had left the country just a week before the Sinai Campaign. I decided now that I wouldn’t miss the next war. The next day I went into the editor’s office and asked to take my two week’s annual leave as of the next day. I had started working at the paper just half a year before and wasn’t yet entitled to leave. But I put my request in such a way – “I’m planning to fly to Israel and would prefer that you consider this my leave” – that he agreed. We agreed that if there was a war I would file stories. But, war or no war, I was to be back in two weeks. I arrived in Israel five days before the war. I had a sister here, Malka, who was a copy editor at the Jerusalem Post so I fell right into a newspaper and social milieu.

Where were you during the war?

In Jerusalem. I spent most of the two days of fighting in the city roaming the border area. It was very exciting and I could say I 'covered' the war, in the sense of writing articles about it, but I had no idea what was going on. The last night I didn’t return to my sister’s apartment to sleep. I didn’t want to waste the time. I just laid down on the grass in a park and slept for a few hours when the Jordanian shelling had stopped. When I got up I wandered over to the Jerusalem Post. One of the editors said there were rumors that Israeli troops were inside the Old City. I suggested we try to get there. We walked to Mandelbaum Gate, the only crossing point between Israeli and Jordanian Jerusalem, to see if we could talk our way past the border guards. But there was no one there, no police, no soldiers. So we just crossed the intersection and found ourselves in Jordanian Jerusalem. There was no one visible but at one point we passed a truck with a dead Jordanian soldier at the wheel. It began to feel spooky but we soon saw Israeli soldiers. They told us to walk around the Old City wall and enter through Lion’s Gate. It was like walking into a particularly dramatic page of history. Unreal. The moment was so enormous you feel outside yourself. The Temple Mount was full of unshaven soldiers, men cheering, officers giving orders, rows of prisoners, planes flying low overhead and then circling over the Jericho road beyond the Mount of Olives. My colleague from the Post continued on to the Western Wall. I stayed behind to talk to half a dozen paratroopers who were drinking bottles of soda they had found in a small Jordanian army enclosure. When I asked them “what now?” one said we should give back all the territory captured in Sinai and the West Bank in exchange for peace (the fighting on the Golan hadn’t started yet), another said we won’t give up anything, another said give them everything except our holy city. The debate which has split Israel in the half century since had begun.

What did you do after the war?

I remember sitting in a café on Agron Street on the last day of the war, summing things up. I had arrived five days before the war. The war had lasted six days. That’s 11 days. I still had three days before I had to return, time enough even for a quick tour of the country. The air over the asphalt in the street was shimmering from the heat but it seemed to be from the excitement. I decided then that I can’t go back, at least not yet. I couldn’t leave this incredible drama at the center of the world for school board meetings and small town politics on Long Island. I sent a telex to the paper apologizing but saying I wouldn’t be returning. I just hung around. That was enough. Soaking everything up. Staying at my sister’s. After a few weeks I saw that I needed a cover story. People kept asking ‘what are you doing?’ what do you intend to do? I decided to say that I’m working on a book. That satisfied everybody. I had never written one and as far as I can remember I didn’t have a particular ambition to write one then. But I felt a need to legitimize myself. The only book I could think of writing was one on the battle for Jerusalem which I had witnessed but didn’t understand. The problem was that all the sharks in world journalism were here. Every one. From every major paper. I was certain there were several Big Names already at work on a new O Jerusalem. I didn’t have a chance against them so I decided that I would aim at the most modest niche I could think of – how civilians in the city had experienced the war.

How did you go about reporting that?

First, I enrolled in a Hebrew language course. There were mostly new immigrants there but also quite a few Arabs from east Jerusalem. The Jews and Arabs got along very nicely. My interviews with civilians began with people I knew through my sister. It didn’t take long to understand that this might add up to a newspaper article but not a book. I needed some input on the battle as well to give a shape to things. I began interviewing local men who had served in the Jerusalem Brigade, a sort of home guard. But there had been two other reservist brigades involved as well – an armored brigade and a paratroop brigade – and most of their men lived elsewhere in the country. They had done the hardest fighting. The story didn’t make sense if I didn’t include them. I began to gather anecdotal information about individuals and small units but this didn’t hang on any stout framework. I needed a broader picture. It wasn’t long before I forgot about a niche. Driven now by my own curiosity I decided to tell the story properly, from the top down and bottom up. It meant intensive traveling around the country. I visited 35 kibbutzim and farming villages, in addition to cities, mostly to speak to paratroopers. That was a great privilege. They were salt of the earth. All the men who fought in Jerusalem were reservists. Sometimes I would be told that the man I was looking for was in the fields and I would be guided to him by the sound of his tractor. I’d get out of the car and walk across the fields to him and fix a time to meet. In all, reporting for the book was one of the richest professional and personal experiences I’ve had. I did 300 interviews, mostly soldiers. I found after awhile that for all their integrity, the soldiers’ testimony could not be relied on blindly. The trauma of war distorts memories. People forget things that happened, sometimes remember things that didn’t happen. Time is often telescoped or reversed. The Rashomon effect. My object was to get overlap. When two men separately tell more or less the same story you can pretty much rely on it. I was putting the pieces of a giant puzzle together. It reached a point where I knew more than they knew – that is, I understood the context better than the person I was talking to because I had spoken to people above him and either side of him.

How long did the project take you?

About two years.

What did you do afterwards?

I married a Hebrew teacher (from another class) and started working as a reporter with The Jerusalem Post.

What kind of reception did your book get?

Almost none. The publisher was the Jewish Publication Society which is not a commercial organization. I don’t believe the book was reviewed by a single non-Jewish paper. There were two or three reviews in small Jewish papers, as I remember. Still, I don’t know how many copies they printed but it sold out. As the 20th anniversary approached, I suggested doing a second edition. They agreed. This time I could give officers’ second names and make corrections. The one problem was that they forgot to include the maps which had been included in the first edition, making the battle hard to follow.

Why did you decided to make still another edition now, 25 years later?

Well, the book was again out of print and I thought that a shame. When I began reading about eBooks I heard a click. This is the way to go. I found a company in England that would do it for a reasonable fee. I decided that this would not just be an electronic reprint. I would add what was missing from the earlier edition – a proper political context, which was not clear immediately after the Six Day War, and to describe the Arab side. I feel I have done the definitive account of a major event in modern Middle East history, not to mention Jewish history.

Did you ever think of writing fiction?

I’ve actually done one, a Middle East shoot-em-up with some archaeology and a bit of mysticism. It failed to interest the three or four people I sent it too. It’s now in my drawer, waiting for courage to return.

Perhaps as an ebook...?

Published on June 03, 2012 04:58

•

Tags:

conflict, israel, israelis, jerusalem, middle-east, six-day-war, war

May 31, 2012

Rees's Rules for Writers

Newspapers and magazines frequently print lists of “rules for writers” penned by supposedly top-notch authors. No doubt this is a trend prompted by the inability of most people to write a clear sentence, let alone a novel. (The growth of texting and email may make us all better writers, of course. We’ll have to wait and see, won’t we….)

Newspapers and magazines frequently print lists of “rules for writers” penned by supposedly top-notch authors. No doubt this is a trend prompted by the inability of most people to write a clear sentence, let alone a novel. (The growth of texting and email may make us all better writers, of course. We’ll have to wait and see, won’t we….)My rules for writers are:

If asked to provide a list of rules for writers, don’t do it.

If you must (because your agent says it’s good for your name to appear in The Guardian), then try not to be cute.

Reveal no stupid prejudices.

Write rules for writers, rather than rules for people who CAN’T write.

Try to have your rules make sense.

I cite here a few of examples of writers who contravene Rees’s rules:

Neil Gaiman’s rules for writers begin: 1. Write.

Cute, huh? Well, not really. A bit of a waste of a rule.

Richard Ford’s Rule #2 is: Don’t have children.

It’s true, of course, that children often force us to look at ourselves and our reactions to them very deeply. They help us to find perspective on the questions that used to seem most important to us. They teach us empathy – for them, and for our parents who used to seem so incompetent and whose behavior we often now repeat. A writer wouldn’t want to develop any of those qualities, would he?

Elmore Leonard’s fourth rule is: Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said.” To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin.

The first part’s fine. But the second part is a rule for people who CAN’T write. The mortal ban on adverbs has become as much a matter of religious observance for many writers as the doctrine of mortal sin itself. Adverbs are fine if you can write. If you CAN’T write, then don’t use adverbs. In fact, don’t use verbs or nouns or adjectives. Don’t write at all. Maybe I should add that to my list of rules for writers: 6. If you can’t write, please don’t write.

Jonathan Franzen’s Rule 5: When information becomes free and universally accessible, voluminous research for a novel is devalued along with it.

I have a degree in English from Oxford with a concentration in critical theory. But I don’t know what the hell this rule is supposed to mean. I hate to offer a correction to Franzen, but an invitation to proffer a list of rules for writers implies that the rules are intended to be acted upon by someone wishing to improve their writing. (Cf. Franzen’s third rule, which tells us never to use the word “then.” Perhaps it, too, is a mortal sin?) Does Franzen’s Fifth Rule suggest that information IS free and universally accessible (though I’ve read that he turns off the internet when he writes) and, therefore, voluminous research has been devalued? Or are we still waiting for free, accessible information? And when it IS devalued, should writers stop researching entirely? Or should they just think of their research as being worth less than it was, but still worth something?

There’s more where that came from, of course. Franzen’s tenth rule is: “You have to love before you can be relentless.” That must be why I didn’t read to the end of “Freedom.”

Other writers pad their list of rules. Margaret Atwood devotes her first four rules to getting hold of a pencil, and paper, and a pencil sharpener, and if you use a computer a “memory stick.” Anne Enright has a rule recommending whisky, but then she’s Irish.

No one’s allowed to repaint the Sistine Chapel, because Michelangelo already did it as well as can be done. That’s how I feel about rules for writers. In “Politics and the English Language” (1946), George Orwell had a Sistine moment and came up with these:

Never use a metaphor, simile, or figure of speech you are used to seeing in print.

Never use a long word where a short one will do.

If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

Never use the passive where you can use the active.

Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

That’s enough for now. I have to sharpen my pencil.

Published on May 31, 2012 03:48

•

Tags:

anne-enright, crime-fiction, elmore-leonard, george-orwell, jonathan-franzen, margaret-atwood, neil-gaiman, richard-ford, rules-for-writers, writing, writing-rules

May 24, 2012

Franzen Bored and Gruelled

Last week I enjoyed a humorous moment at the expense of Lisa Scottoline and the New York Times, which had described her writing schedule (supposedly from 9 a.m. until 11.30 p.m. and two novels a year) as “brutal.” I pointed out that if Scottoline was an ill-paid hooker, her schedule would be brutal. As a pretty well-remunerated writer––even one who works long hours––she’s still spending her days on an intellectual pool chair.

Last week I enjoyed a humorous moment at the expense of Lisa Scottoline and the New York Times, which had described her writing schedule (supposedly from 9 a.m. until 11.30 p.m. and two novels a year) as “brutal.” I pointed out that if Scottoline was an ill-paid hooker, her schedule would be brutal. As a pretty well-remunerated writer––even one who works long hours––she’s still spending her days on an intellectual pool chair.No sooner had I zapped those musings into the ether, to be read and appreciated (or abused) by virtual millions, than I was faced with another example of journalistic/authorial victimhood. In a review of the vastly overrated Jonathan Franzen’s new book of essays, poor Jonathan is described as heading off to the South Pacific to do some bird-watching and to recharge his batteries after “a grueling, boring book tour.”

Oh, sure, it’s tough traveling around talking about yourself and your work and your intellectual interests to people who take the time to buy your books and read them and are still interested enough in you to want to hear your other thoughts. Book tours are neither boring nor gruelling. Climbing K2 is grueling. Reading Jonathan Franzen is boring.

If your book tour is boring, that’s because you or your book or both are boring. If it’s grueling, it’s because you lack the meditative quality that allows you to simply be where you are, doing what you’re doing (and therefore you get “bored” because you’d rather be back at your desk where you’re a “pure” artist, than, say, talking to lovely people about your books in Hamburg with the impure intention of getting them to buy more books.)

The second amusing aspect of this (for there is, as pseudo-intellectual Franzen might write, a stereographic plurality of meanings here) is that the Times highlights an essay by Franzen in which he tells a graduating class at Kenyon College to get their noses out of their social networking devices and experience the world. Somehow a book tour doesn’t represent the real world to him. The South Pacific does. But the fast-disappearing bookshops of America are merely boring and grueling.

As a former journalist, I understand that there’s a degree of what I call cliché-habit involved in the word choice here. Schedules have to be “brutal” and book tours are “grueling,” just as Saddam Hussein was always the “Iraqi strongman,” until we found out he wasn’t.

But writers who go along with such descriptions will end up seeing their role with a negative, self-pitying slant. If you’re a writer who thinks your schedule is “brutal,” you’ll feel exhausted. You’ll write tired old shit with no spark to it. If you’re a writer who thinks book tours are “boring and grueling,” you’ll end up flouncing on your bed with a box of tissues and a tisane like any number of luvvies from Truman Capote onward, because the world is simply too much. You’ll never enjoy a book that truly grips you and tells you about the world in which life is lived; you’d rather be bird-watching in the South Pacific and writing stories of domestic life that are so pedestrian they find themselves described with that other most dreadful of clichés: “seminal.

Published on May 24, 2012 02:46

•

Tags:

book-tours, jonathan-franzen, reviews, writers, writing

May 23, 2012

Likeable Schmikeable: Jasmine Schwartz’s Writing Life interview

The hottest new voice in crime fiction is Jasmine Schwartz. Her great debut “Farbissen” and its follow-up “Fakakt” have earned plaudits for her and for her detective, neurotic New York fashionista Melissa Morris. The books have been called “Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies.” But Jasmine’s no Renee Zellweger softie, as you’ll see from her hilarious blog. Personally (to misquote a Zellweger line) she had me at the titles. Farbissen means "embittered" in Yiddish, while Fakakt means "screwed." Both her novels are stylish and very funny, but they also tackle important social issues, like race and sex trafficking. Jasmine chats about the way she writes, and why:

The hottest new voice in crime fiction is Jasmine Schwartz. Her great debut “Farbissen” and its follow-up “Fakakt” have earned plaudits for her and for her detective, neurotic New York fashionista Melissa Morris. The books have been called “Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies.” But Jasmine’s no Renee Zellweger softie, as you’ll see from her hilarious blog. Personally (to misquote a Zellweger line) she had me at the titles. Farbissen means "embittered" in Yiddish, while Fakakt means "screwed." Both her novels are stylish and very funny, but they also tackle important social issues, like race and sex trafficking. Jasmine chats about the way she writes, and why:Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

The book is FARBISSEN: MELISSA MORRIS AND THE MEANING OF MONEY. The novel follows some conventions of a mystery series, while ignoring others completely. It incorporates humor with serious themes, such as depression and racism. As a reader, this is always my favorite kind of writing – when I laugh but also have a deeper, emotional reaction.

The book is FARBISSEN: MELISSA MORRIS AND THE MEANING OF MONEY. The novel follows some conventions of a mystery series, while ignoring others completely. It incorporates humor with serious themes, such as depression and racism. As a reader, this is always my favorite kind of writing – when I laugh but also have a deeper, emotional reaction.How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write? Or as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Agents and Publishers like to say, about protagonists, "Make them likeable. Every woman should want to be your main character." I always hated that. I love David Sedaris because he can take his deepest flaws, look them in the eye, and make them the centerpiece of his essays. That's who I want to read. Emotional honesty is so much more compelling then a whitewashed character.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

"The story so far: In the beginning the Universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move." Douglas Adams started The Restaurant at the End of the Universe with that. Why do I love it? Simple. I grew up religious, educated by Rabbis and with an education that begged us not to question the basic concepts of our faith. "In the beginning" is the first sentence of "adult" literature I learned, at age five. But I think Douglas wrote it better.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Martin Cruz Smith comes to mind. Larry McMurtry is wonderful. Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall and A Place of Greater Safety were both phenomenal.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Dennis Lehane's Shutter Island was awesome.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

I was on the train with my husband. He was considering writing a detective series, and we were brainstorming different sleuths. I said, "How about writing one about a neurotic New Yorker?" Then I realized I should do that one.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

The childhood stuff gets you started writing when you're young, I think. But then, if you continue writing, it's for different reasons. For me, writing brings out my creative energy and taps into my spiritual side. That’s all hard to remember when you confront the commercial aspect of the craft [i.e. selling your work], but it's important to remember this motivation at the core.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

My husband is the greatest resource ever for such ideas. I guess that's not doing it myself, but I do feed him.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

Aliens on Long Island. Lost tribes and lost souls. Mass face-lifts. It’s sci-fi, baby, sci-fi.

Published on May 23, 2012 09:33

•

Tags:

chick-lit, crime-fiction, how-to-write, women-s-fiction, writers, writing-interviews, writing-life, yiddish

Likeable Schmikeable: Jasmine Schwartz’s Writing Life interview

The hottest new voice in crime fiction is Jasmine Schwartz. Her great debut “Farbissen” and its follow-up “Fakakt” have earned plaudits for her and for her detective, neurotic New York fashionista Melissa Morris. The books have been called “Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies.” But Jasmine’s no Renee Zellweger softie, as you’ll see from her hilarious blog. Personally (to misquote a Zellweger line) she had me at the titles. Farbissen means "embittered" in Yiddish, while Fakakt means "screwed." Both her novels are stylish and very funny, but they also tackle important social issues, like race and sex trafficking. Jasmine chats about the way she writes, and why:

The hottest new voice in crime fiction is Jasmine Schwartz. Her great debut “Farbissen” and its follow-up “Fakakt” have earned plaudits for her and for her detective, neurotic New York fashionista Melissa Morris. The books have been called “Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies.” But Jasmine’s no Renee Zellweger softie, as you’ll see from her hilarious blog. Personally (to misquote a Zellweger line) she had me at the titles. Farbissen means "embittered" in Yiddish, while Fakakt means "screwed." Both her novels are stylish and very funny, but they also tackle important social issues, like race and sex trafficking. Jasmine chats about the way she writes, and why:Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

The book is FARBISSEN: MELISSA MORRIS AND THE MEANING OF MONEY. The novel follows some conventions of a mystery series, while ignoring others completely. It incorporates humor with serious themes, such as depression and racism. As a reader, this is always my favorite kind of writing – when I laugh but also have a deeper, emotional reaction.

The book is FARBISSEN: MELISSA MORRIS AND THE MEANING OF MONEY. The novel follows some conventions of a mystery series, while ignoring others completely. It incorporates humor with serious themes, such as depression and racism. As a reader, this is always my favorite kind of writing – when I laugh but also have a deeper, emotional reaction.How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write? Or as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Agents and Publishers like to say, about protagonists, "Make them likeable. Every woman should want to be your main character." I always hated that. I love David Sedaris because he can take his deepest flaws, look them in the eye, and make them the centerpiece of his essays. That's who I want to read. Emotional honesty is so much more compelling then a whitewashed character.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

"The story so far: In the beginning the Universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move." Douglas Adams started The Restaurant at the End of the Universe with that. Why do I love it? Simple. I grew up religious, educated by Rabbis and with an education that begged us not to question the basic concepts of our faith. "In the beginning" is the first sentence of "adult" literature I learned, at age five. But I think Douglas wrote it better.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Martin Cruz Smith comes to mind. Larry McMurtry is wonderful. Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall and A Place of Greater Safety were both phenomenal.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

Dennis Lehane's Shutter Island was awesome.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

I was on the train with my husband. He was considering writing a detective series, and we were brainstorming different sleuths. I said, "How about writing one about a neurotic New Yorker?" Then I realized I should do that one.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

The childhood stuff gets you started writing when you're young, I think. But then, if you continue writing, it's for different reasons. For me, writing brings out my creative energy and taps into my spiritual side. That’s all hard to remember when you confront the commercial aspect of the craft [i.e. selling your work], but it's important to remember this motivation at the core.

What’s the best idea for marketing a book you can do yourself?

My husband is the greatest resource ever for such ideas. I guess that's not doing it myself, but I do feed him.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

Aliens on Long Island. Lost tribes and lost souls. Mass face-lifts. It’s sci-fi, baby, sci-fi.

Published on May 23, 2012 09:33

•

Tags:

chick-lit, crime-fiction, how-to-write, women-s-fiction, writers, writing-interviews, writing-life, yiddish

May 22, 2012

FREE story download Weds thru Friday

My short story THE SWEETEST THINGS will be free for download on amazon's Kindle from Wednesday until Friday. It's set in Amman, Jordan, against the backdrop of the Arab Spring. Tom Swallow, a Western journalist, befriends a wealthy sweet-seller named Said. He grows close to Said and his lover, a poor taxi driver named Nizar, as he covers the anti-government riots of the Arab Spring. He observes their growing conflict until its shocking conclusion. The story draws on my many years reporting and, for a while, living in the Jordanian capital, which finds itself at the seething center of the Mideast’s many conflicts. Go to the US edition. For the UK edition.

My short story THE SWEETEST THINGS will be free for download on amazon's Kindle from Wednesday until Friday. It's set in Amman, Jordan, against the backdrop of the Arab Spring. Tom Swallow, a Western journalist, befriends a wealthy sweet-seller named Said. He grows close to Said and his lover, a poor taxi driver named Nizar, as he covers the anti-government riots of the Arab Spring. He observes their growing conflict until its shocking conclusion. The story draws on my many years reporting and, for a while, living in the Jordanian capital, which finds itself at the seething center of the Mideast’s many conflicts. Go to the US edition. For the UK edition.

Published on May 22, 2012 00:36

•

Tags:

arab-spring, crime-fiction, middle-east, promotions, short-story

May 19, 2012

Megaselling Thriller Writers' Brutal Sked

I’ve always considered myself lucky to be a writer. True, I work long hours…compared to the purely idle rich or to a top soccer player who puts in a tough 90-minute week. But essentially the burden on a writer is less the hours spent at writing – which ought to be fun – and more the occasional pondering about one’s self-worth, about one’s writing itself, and about one’s status in the author’s pantheon from piffling to powerful.

I’ve always considered myself lucky to be a writer. True, I work long hours…compared to the purely idle rich or to a top soccer player who puts in a tough 90-minute week. But essentially the burden on a writer is less the hours spent at writing – which ought to be fun – and more the occasional pondering about one’s self-worth, about one’s writing itself, and about one’s status in the author’s pantheon from piffling to powerful.Which is why I was amused by the caption to The New York Times’s article this weekfeaturing crime writers who’re now being asked by publishers and agents to write short stories and extra features to help publicize their novels – or even to write a second novel a year. (In the print version, though not on the web) the caption told us that Lisa Scottoline works “a brutal writing schedule” which sees her tapping away from 9 a.m. “until Colbert” comes on at 11.30.

My great-grandfather had a brutal schedule working in a Welsh coal mine. The Chinese who make the little plastic thingamy bits of crap I toss out every day have a brutal schedule. A hooker has a brutal schedule. For your schedule to be brutal, your work also has to be brutal.

No writer has a brutal schedule. In fact, no one who works in an office has a brutal schedule. Long hours in an office are boring, but not brutal.

The Times article led me to consider the pressure on (and personality of) the mega-selling thriller writer type. I’ve bumped into a few of them at book fairs. I’ve found them to be mostly contented, charming and fun, and yet… they all seem to feel a good deal of pressure from agents and publishers. In the past (and still, no doubt) that pressure was limited to the desire of the agent and publisher that Ms. Megaseller would resist the temptation to write a standalone novel and come up with another in their hugely popular series. The writers in question never seemed keen to do yet another installment of “McIrishname and the Gimp,” or whatever their series was called. I found it more than mildly astonishing that even with millions in the bank, all these writers claimed to find it hard to resist the blandishments of their publishers.

As if the nearly bankrupt denizens of the publishing fraternity would dump Ms. Megaseller if she put McIrishname and the Gimp out to grass for 18 months, while she knocked out a stand-alone about a murder during the Westphalian pumpernickel crisis of 1384. (I’ve a mind to send a proposal on that to my agent…)

Equally: as if publishers might put aside their fear of a future of thin e-book margins and dump Ms. Megaseller if she didn’t write two novels in a year.

Now I’ve been known to do a bit of extra stuff for my good readers. I’ve made videos for my books. I’ve put out some short stories for Kindle. I’ve even recorded an album of original songs about my books. I’m willing to go that extra mile. But there’s a risk to producing more than…well, more than I produce.

Some time ago I asked my agent — while she was lunching me on sushi on Park Avenue during a three-week break in my brutal writing schedule – if she thought I should try to write two books a year. I pointed out that I was quite efficient and that I wrote quickly and didn’t really work very long hours. I could up the productivity, perhaps, if she thought it’d be good for my career. She told me I shouldn’t.

“Because one of the two novels a year might be crap?” I asked.

“Weeeeell, no,” she said. She’s very polite. She’s from the Midwest.

I twigged. “Ah, you’re worried BOTH of them might be crap.”

She nodded and pushed the sushi boat my way.

Writing too much during the course of a day drains the creative energy. Larry McMurtry has said you ought to stop before you’re played out, because otherwise you’ll be mentally too exhausted to pick up and continue the next day. I assume McMurty quits long before Colbert comes on. (I assume that, as a 76-year-old who lives near Wichita Falls, Texas, old Larry’s in bed before Colbert comes on.)

The message implicit in the Times’s quote from an Oregon lawyer who downloaded a short-story by Lee Child that was a teaser for a forthcoming novel (“I’ll give anything he writes a shot”) is that it doesn’t matter if a mega-seller writes crap. (Notice the appreciation and, yet, the lack of enthusiasm in that quote.) Plenty of people will still download it.

Michael Caine once said that he made three movies a year. A brutal schedule. “Two of them may be rubbish,” he said, “but one of them will be good, and that’s the one people will remember.” It won’t work that way for books. (Unless maybe you get a stable of little writer- chimps to bang them out for you, and even that doesn’t seem to work on a literary level, though they do sell, which proves my point. Anyhow that’s for another blog post.)

Meanwhile, I’m working on a short story about Caravaggio, which I intend to publish for digital download shortly before the July 1 UK publication of my novel about the great Italian artist “A Name in Blood”.

I assure you, it’s not crap.

Published on May 19, 2012 09:49

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, lee-child, lisa-scottoline, thrillers, writers, writing

May 9, 2012

Jasmine Schwartz: Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies

I hok you no chainik when I recommend you read "Farbissen" and "Fakakt," the great new crime novels of Jasmine Schwartz. Jasmine is an important and hilarious new voice in crime fiction -- and that's no shmontses! Her first two novels "Farbissen: Melissa Morris and the Meaning of Money" and "Fakakt: Melissa Morris and the Meaning of Sex" use Yiddish words for their titles. When you read the stories of Melissa Morris, a neurotic and fashion-obsessed New Yorker, you'll see why... And we'll be finding out here, too, as Jasmine is going to be doing an interview with us in a couple of days, taking a break from her troubles with a father who's remarrying, the musings of her "future ex-husband," and her ongoing struggle to enter the top 1 percent of US taxpayers, as you'll see from her blog.

I hok you no chainik when I recommend you read "Farbissen" and "Fakakt," the great new crime novels of Jasmine Schwartz. Jasmine is an important and hilarious new voice in crime fiction -- and that's no shmontses! Her first two novels "Farbissen: Melissa Morris and the Meaning of Money" and "Fakakt: Melissa Morris and the Meaning of Sex" use Yiddish words for their titles. When you read the stories of Melissa Morris, a neurotic and fashion-obsessed New Yorker, you'll see why... And we'll be finding out here, too, as Jasmine is going to be doing an interview with us in a couple of days, taking a break from her troubles with a father who's remarrying, the musings of her "future ex-husband," and her ongoing struggle to enter the top 1 percent of US taxpayers, as you'll see from her blog.

Published on May 09, 2012 03:56

•

Tags:

crime-fiction, fakakt, farbissen, jasmine-schwartz, jewish, jews, yiddish