Matt Rees's Blog, page 10

June 22, 2012

Caravaggio Masterpieces that Inspired My Novel A NAME IN BLOOD

The heart of my novel A NAME IN BLOOD, out in the UK on 5 July, is my love of Caravaggio's paintings. Though the idea for the novel comes from the Italian maestro's mysterious disappearance and death, it was these works which drew me to him. Here are some of the paintings that feature in the novel.

[caption id="attachment_2462" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Calling of Saint Matthew, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome"] [/caption]

[/caption]

The three "Matthew" paintings in the French church made Caravaggio's reputation. They were his first great "history paintings," which at the time meant paintings of notable biblical scenes. His light-dark (chiaroscuro) technique is most evident in "The Calling." Many's the hour I've spent in the corner of San Luigi, feeding Euros into the light-meter so I can marvel at this work. Usually critics think Matthew is the old fellow third from left. But I think he's pointing at the youth with his head down...

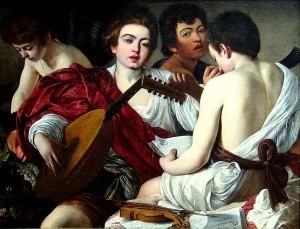

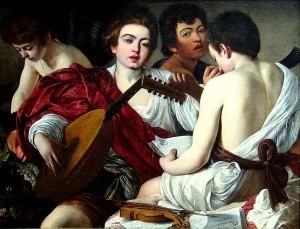

[caption id="attachment_2466" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Musicians, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York"] [/caption] Young Caravaggio's self-portrait is second from the right. 1595, age 23 or 24.

[/caption] Young Caravaggio's self-portrait is second from the right. 1595, age 23 or 24.

[caption id="attachment_2467" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="St Catherine of Alexandria, Fondacion Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid"] [/caption] This painting first made me fall in love with Caravaggio. I was alone with it in the room where it's housed. The saint, who's about to meet her death, seemed to watch me. I couldn't leave. It was as though I was abandoning her to her fate, so present did she seem. So I stayed a long time and...couldn't help but think about a novel... The model is Fillide, who appears in A NAME IN BLOOD.

[/caption] This painting first made me fall in love with Caravaggio. I was alone with it in the room where it's housed. The saint, who's about to meet her death, seemed to watch me. I couldn't leave. It was as though I was abandoning her to her fate, so present did she seem. So I stayed a long time and...couldn't help but think about a novel... The model is Fillide, who appears in A NAME IN BLOOD.

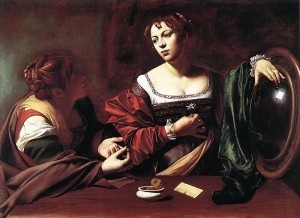

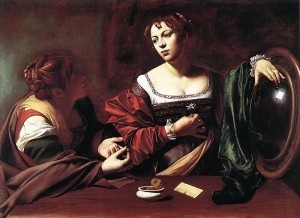

[caption id="attachment_2472" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Martha and Mary Magdalene, Institute of Fine Arts, Detroit"] [/caption]Fillide again, with a second woman whose beauty is so much greater for the way Caravaggio disguises her in the shadow. The convex mirror may be a clue to Caravaggio's use of projected images to help him paint.

[/caption]Fillide again, with a second woman whose beauty is so much greater for the way Caravaggio disguises her in the shadow. The convex mirror may be a clue to Caravaggio's use of projected images to help him paint.

[caption id="attachment_2473" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Portrait of Pope Paul V, Palazzo Borghese (private collection), Rome"] [/caption]The nasty, grasping little eyes of the Pope truly raise the hairs on the back of your neck when you're before this painting. Caravaggio was no flatterer.

[/caption]The nasty, grasping little eyes of the Pope truly raise the hairs on the back of your neck when you're before this painting. Caravaggio was no flatterer.

[caption id="attachment_2474" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Madonna of Loreto, Church of Sant'Agostino, Rome"] [/caption]In A NAME IN BLOOD, this is how Caravaggio sees Lena Antognetti -- the model for this Virgin -- on the doorstep of her rundown home.

[/caption]In A NAME IN BLOOD, this is how Caravaggio sees Lena Antognetti -- the model for this Virgin -- on the doorstep of her rundown home.

[caption id="attachment_2475" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, Galleria Doria Pamphilij, Rome"] [/caption]The model for the auburn-headed virgin, Anna Bianchini, died of syphilis.

[/caption]The model for the auburn-headed virgin, Anna Bianchini, died of syphilis.

[caption id="attachment_2476" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Death of the Virgin, Musee du Louvre, Paris"] [/caption]Convention had the Virgin rising up to heaven with the angels. Caravaggio painted her -- Lena in this case -- as an absolutely dead woman. It looks better to us, for that reason. It also looked blasphemous to many contemporaries.

[/caption]Convention had the Virgin rising up to heaven with the angels. Caravaggio painted her -- Lena in this case -- as an absolutely dead woman. It looks better to us, for that reason. It also looked blasphemous to many contemporaries.

[caption id="attachment_2477" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Madonna with the Serpent, Galleria Borghese, Rome"] [/caption]For me, simply the greatest painting ever. Much of what happens in A NAME IN BLOOD was dictated by the attraction I felt to the Madonna here -- or more specifically to Lena, Caravaggio's model.

[/caption]For me, simply the greatest painting ever. Much of what happens in A NAME IN BLOOD was dictated by the attraction I felt to the Madonna here -- or more specifically to Lena, Caravaggio's model.

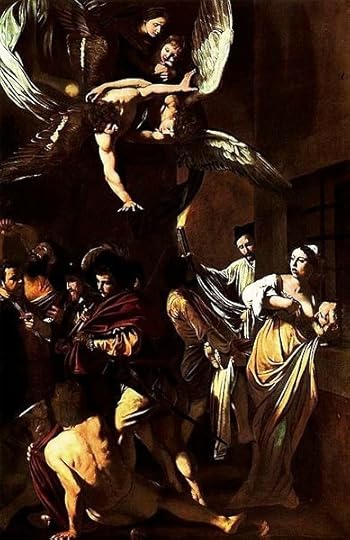

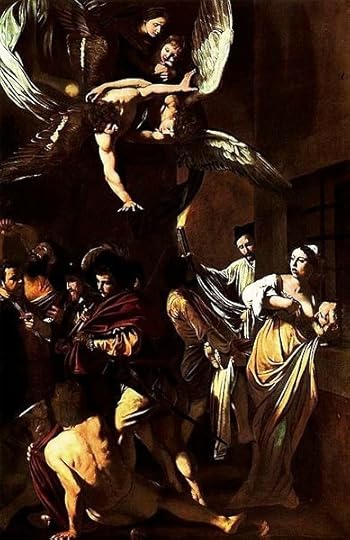

[caption id="attachment_2479" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Our Lady of Mercy (Seven Works of Mercy), Chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples"] [/caption]I stood a very long time before this painting. The street noise was loud from outside. I saw how connected Caravaggio was to ordinary people. So connected that he made them his saints and martyrs. The Madonna is, once again, Lena.

[/caption]I stood a very long time before this painting. The street noise was loud from outside. I saw how connected Caravaggio was to ordinary people. So connected that he made them his saints and martyrs. The Madonna is, once again, Lena.

[caption id="attachment_2481" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt, Musee du Louvre, Paris"] [/caption]Is this a portrait of the Grand Master or of the young boy who was his page? Caravaggio, as usual, doesn't take the traditional path.

[/caption]Is this a portrait of the Grand Master or of the young boy who was his page? Caravaggio, as usual, doesn't take the traditional path.

[caption id="attachment_2482" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Beheading of St John the Baptist, Co-Cathedral of St John, Valletta, Malta"] [/caption]Standing in the cavernous oratory where this masterpiece hangs is like watching a movie unfold before you. It's a still image, yet Caravaggio captured what went before and what was to come. I believe he changed his technique to make this possible. It's central to the art story-arc of A NAME IN BLOOD.

[/caption]Standing in the cavernous oratory where this masterpiece hangs is like watching a movie unfold before you. It's a still image, yet Caravaggio captured what went before and what was to come. I believe he changed his technique to make this possible. It's central to the art story-arc of A NAME IN BLOOD.

[caption id="attachment_2484" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Flagellation of Christ, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples"] [/caption]The Flagellation is approached down a long gallery through other smaller galleries at the Capodimonte. Though you pass by masterpieces by Raphael et al, you have eyes only for this shocking, shadowy work. No artist can make everything else in a gallery seem like rubbish the way Caravaggio can.

[/caption]The Flagellation is approached down a long gallery through other smaller galleries at the Capodimonte. Though you pass by masterpieces by Raphael et al, you have eyes only for this shocking, shadowy work. No artist can make everything else in a gallery seem like rubbish the way Caravaggio can.

[caption id="attachment_2486" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Denial of St Peter, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York"] [/caption]At the end, Caravaggio pushed the darkness to an extreme. Look how it lifts the most important details -- the gesture and face of Peter -- out into the light.

[/caption]At the end, Caravaggio pushed the darkness to an extreme. Look how it lifts the most important details -- the gesture and face of Peter -- out into the light.

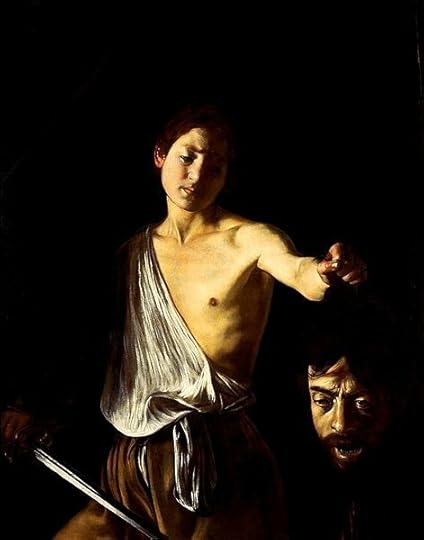

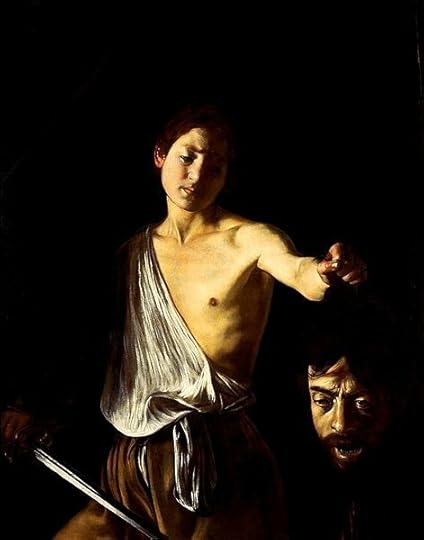

[caption id="attachment_2488" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="David with the Head of Goliath, Galleria Borghese, Rome"] [/caption]The most horrifying and personal of Caravaggio's biblical images. Probably the last thing he painted, while he was in Naples in 1610.

[/caption]The most horrifying and personal of Caravaggio's biblical images. Probably the last thing he painted, while he was in Naples in 1610.

[caption id="attachment_2462" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Calling of Saint Matthew, Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome"]

[/caption]

[/caption]The three "Matthew" paintings in the French church made Caravaggio's reputation. They were his first great "history paintings," which at the time meant paintings of notable biblical scenes. His light-dark (chiaroscuro) technique is most evident in "The Calling." Many's the hour I've spent in the corner of San Luigi, feeding Euros into the light-meter so I can marvel at this work. Usually critics think Matthew is the old fellow third from left. But I think he's pointing at the youth with his head down...

[caption id="attachment_2466" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Musicians, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York"]

[/caption] Young Caravaggio's self-portrait is second from the right. 1595, age 23 or 24.

[/caption] Young Caravaggio's self-portrait is second from the right. 1595, age 23 or 24.[caption id="attachment_2467" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="St Catherine of Alexandria, Fondacion Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid"]

[/caption] This painting first made me fall in love with Caravaggio. I was alone with it in the room where it's housed. The saint, who's about to meet her death, seemed to watch me. I couldn't leave. It was as though I was abandoning her to her fate, so present did she seem. So I stayed a long time and...couldn't help but think about a novel... The model is Fillide, who appears in A NAME IN BLOOD.

[/caption] This painting first made me fall in love with Caravaggio. I was alone with it in the room where it's housed. The saint, who's about to meet her death, seemed to watch me. I couldn't leave. It was as though I was abandoning her to her fate, so present did she seem. So I stayed a long time and...couldn't help but think about a novel... The model is Fillide, who appears in A NAME IN BLOOD.[caption id="attachment_2472" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Martha and Mary Magdalene, Institute of Fine Arts, Detroit"]

[/caption]Fillide again, with a second woman whose beauty is so much greater for the way Caravaggio disguises her in the shadow. The convex mirror may be a clue to Caravaggio's use of projected images to help him paint.

[/caption]Fillide again, with a second woman whose beauty is so much greater for the way Caravaggio disguises her in the shadow. The convex mirror may be a clue to Caravaggio's use of projected images to help him paint.[caption id="attachment_2473" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Portrait of Pope Paul V, Palazzo Borghese (private collection), Rome"]

[/caption]The nasty, grasping little eyes of the Pope truly raise the hairs on the back of your neck when you're before this painting. Caravaggio was no flatterer.

[/caption]The nasty, grasping little eyes of the Pope truly raise the hairs on the back of your neck when you're before this painting. Caravaggio was no flatterer.[caption id="attachment_2474" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Madonna of Loreto, Church of Sant'Agostino, Rome"]

[/caption]In A NAME IN BLOOD, this is how Caravaggio sees Lena Antognetti -- the model for this Virgin -- on the doorstep of her rundown home.

[/caption]In A NAME IN BLOOD, this is how Caravaggio sees Lena Antognetti -- the model for this Virgin -- on the doorstep of her rundown home.[caption id="attachment_2475" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, Galleria Doria Pamphilij, Rome"]

[/caption]The model for the auburn-headed virgin, Anna Bianchini, died of syphilis.

[/caption]The model for the auburn-headed virgin, Anna Bianchini, died of syphilis.[caption id="attachment_2476" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Death of the Virgin, Musee du Louvre, Paris"]

[/caption]Convention had the Virgin rising up to heaven with the angels. Caravaggio painted her -- Lena in this case -- as an absolutely dead woman. It looks better to us, for that reason. It also looked blasphemous to many contemporaries.

[/caption]Convention had the Virgin rising up to heaven with the angels. Caravaggio painted her -- Lena in this case -- as an absolutely dead woman. It looks better to us, for that reason. It also looked blasphemous to many contemporaries.[caption id="attachment_2477" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Madonna with the Serpent, Galleria Borghese, Rome"]

[/caption]For me, simply the greatest painting ever. Much of what happens in A NAME IN BLOOD was dictated by the attraction I felt to the Madonna here -- or more specifically to Lena, Caravaggio's model.

[/caption]For me, simply the greatest painting ever. Much of what happens in A NAME IN BLOOD was dictated by the attraction I felt to the Madonna here -- or more specifically to Lena, Caravaggio's model.[caption id="attachment_2479" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Our Lady of Mercy (Seven Works of Mercy), Chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, Naples"]

[/caption]I stood a very long time before this painting. The street noise was loud from outside. I saw how connected Caravaggio was to ordinary people. So connected that he made them his saints and martyrs. The Madonna is, once again, Lena.

[/caption]I stood a very long time before this painting. The street noise was loud from outside. I saw how connected Caravaggio was to ordinary people. So connected that he made them his saints and martyrs. The Madonna is, once again, Lena.[caption id="attachment_2481" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt, Musee du Louvre, Paris"]

[/caption]Is this a portrait of the Grand Master or of the young boy who was his page? Caravaggio, as usual, doesn't take the traditional path.

[/caption]Is this a portrait of the Grand Master or of the young boy who was his page? Caravaggio, as usual, doesn't take the traditional path.[caption id="attachment_2482" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Beheading of St John the Baptist, Co-Cathedral of St John, Valletta, Malta"]

[/caption]Standing in the cavernous oratory where this masterpiece hangs is like watching a movie unfold before you. It's a still image, yet Caravaggio captured what went before and what was to come. I believe he changed his technique to make this possible. It's central to the art story-arc of A NAME IN BLOOD.

[/caption]Standing in the cavernous oratory where this masterpiece hangs is like watching a movie unfold before you. It's a still image, yet Caravaggio captured what went before and what was to come. I believe he changed his technique to make this possible. It's central to the art story-arc of A NAME IN BLOOD.[caption id="attachment_2484" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Flagellation of Christ, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples"]

[/caption]The Flagellation is approached down a long gallery through other smaller galleries at the Capodimonte. Though you pass by masterpieces by Raphael et al, you have eyes only for this shocking, shadowy work. No artist can make everything else in a gallery seem like rubbish the way Caravaggio can.

[/caption]The Flagellation is approached down a long gallery through other smaller galleries at the Capodimonte. Though you pass by masterpieces by Raphael et al, you have eyes only for this shocking, shadowy work. No artist can make everything else in a gallery seem like rubbish the way Caravaggio can.[caption id="attachment_2486" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="The Denial of St Peter, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York"]

[/caption]At the end, Caravaggio pushed the darkness to an extreme. Look how it lifts the most important details -- the gesture and face of Peter -- out into the light.

[/caption]At the end, Caravaggio pushed the darkness to an extreme. Look how it lifts the most important details -- the gesture and face of Peter -- out into the light.[caption id="attachment_2488" align="aligncenter" width="520" caption="David with the Head of Goliath, Galleria Borghese, Rome"]

[/caption]The most horrifying and personal of Caravaggio's biblical images. Probably the last thing he painted, while he was in Naples in 1610.

[/caption]The most horrifying and personal of Caravaggio's biblical images. Probably the last thing he painted, while he was in Naples in 1610.

Published on June 22, 2012 04:22

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction

June 20, 2012

FREE Caravaggio short story download

My historical crime novel about the mysterious end of Caravaggio is out in the UK in a couple of weeks. As a taster for A NAME IN BLOOD, I'm making available a short story "Lazarus's Brush" that's also about the great Italian artist. The download is FREE until Sunday. It includes the short story, plus a sample chapter from the novel and a personal essay about how I came to write A NAME IN BLOOD. (A bit like all the extra stuff you get on a DVD, but without the "commentary" track. Maybe I'll do one of those on my Podcast some time....Well, if you do listen to the Podcast, you can hear me talking about how I wrote A NAME IN BLOOD and reading a chapter already.) In the short story "Lazarus's Brush," Caravaggio flees to Sicily with a price on his head. Commissioned to paint the raising of Lazarus, he learns about his fears of the violence that stalks him. But the story also charts a profound change in his artistic technique. It's an episode I didn't include in the novel, but it's a compelling moment in Caravaggio's life and work nonetheless. Download the US version. Get the UK edition. The Caravaggio painting at the heart of "Lazarus's Brush" has just been restored, by the way. You can read more about the restoration here.

Published on June 20, 2012 00:23

•

Tags:

art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, free-promotion, free-short-story, historical-fiction, historical-thriller, raising-of-lazarus, renaissance

June 18, 2012

Dafter than a Fattening Donut: The Dumbing Down of Superman

My guest blogger today is superhot crime novel phenom Jasmine Schwartz. Jasmine is the author of Farbissen: Melissa Morris and the Meaning of Money and Fakakt: Melissa Morris and the Meaning of Sex, which have been called "Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies." Today she brings her incisive wit to bear on the original Superman comics:

My guest blogger today is superhot crime novel phenom Jasmine Schwartz. Jasmine is the author of Farbissen: Melissa Morris and the Meaning of Money and Fakakt: Melissa Morris and the Meaning of Sex, which have been called "Bridget Jones with guns and dead bodies." Today she brings her incisive wit to bear on the original Superman comics:Yesterday was my future ex-husband's birthday. Hooray for him. I say that with all the fake enthusiasm I can muster.

I tussled with a few Russian mistresses to get the last Tonino Lamborghini cigar lighter, but I admit that the best gift was given to him by his brother -- an original Superman comic book. Have you read it lately? I almost cried. Everything that's wrong with the world is exposed within its poorly illustrated pages. Screw Batman. This is the real deal.

They'd never publish this little gem today. A few details about the original you probably wished you didn't know:

Lois Lane is an Unreconstructed, Superficial Bitch

Lois is unabashedly mean and insensitive. She avoids the gutless Clark Kent and calls him a "spineless, unbearable coward." Hear, hear, sister. Kent can't even get a sentence out without stuttering and has to beg his way into tabloid journalism. Modern versions of this story have Lois being nice to him, and turn Kent into a funny, sympathetic character. But Jerry Seigel and Joe Shuster -- the original writers -- weren't afraid to hate this powerless, simpering hack. Tell it like it is, Jewish boys. Tell it like it is.

Superman is a Misogynist and a Bully

Kidnapping and drugging an innocent football player, beating up the governor's butler who's only trying to do his job, leading a party of wealthy people down a mine shaft to be buried alive -- there's nothing this man of steel won't do to prove a vague point. If there's a simple way to achieve justice, Superman is sure to ignore it and hatch an ill-conceived and convoluted plan instead.

The Plot Makes No Sense

Does Superman teach the bad guy a lesson? He sure does. It only takes him about a year or so to force the corrupt Senator Barrows to name Emil Norvell, kidnap Norvell, force him to set sail on a steamer, save him from his own henchmen, force him to enlist in an army, join the same army himself, kidnap the opposing generals, and then allow Norvell to return home unscathed. Who needs bloated, bureaucratic government when Superman is around?

And so we come to the question: Why did we dumb down Superman? Why betray the original vision of this erratic prick and make him into a feeble, soft-minded moderate? Now he's dafter than a fattening donut, more banal than a supermarket olive, and able to keep mall children in a red-cape jam.

Published on June 18, 2012 03:43

•

Tags:

comics, crime-fiction, guest-post, jasmine-schwartz, superman

June 15, 2012

My Caravaggio songs: The music of A NAME IN BLOOD

Art ought to inspire us at least to try to work in all the media to which we have access. I'm a writer. But I love to make music, which is partially why I wrote about the mystery of the great composer's death in Mozart's Last Aria. Writing that novel took me deeper inside some great music and helped me develop my own playing. The same is true of painting. For my new novel, A NAME IN BLOOD, I learned to work with oils. But I also wanted to incorporate these different interests. The result was my Poisonville project: original music about crime fiction. Two of the songs I've recorded are about A Name in Blood.

Art ought to inspire us at least to try to work in all the media to which we have access. I'm a writer. But I love to make music, which is partially why I wrote about the mystery of the great composer's death in Mozart's Last Aria. Writing that novel took me deeper inside some great music and helped me develop my own playing. The same is true of painting. For my new novel, A NAME IN BLOOD, I learned to work with oils. But I also wanted to incorporate these different interests. The result was my Poisonville project: original music about crime fiction. Two of the songs I've recorded are about A Name in Blood.“A Name in Blood,” is released in the UK July 5. It's about the mystery of Caravaggio's disappearance. In July 1610, he was on the run with a price on his head and he simply disappeared. Art historians have accepted a fairly tall tale about how this happened. My novel is my answer.

Caravaggio was a rebellious, sensitive man who changed art. In writing music for the book, I thought of a kind of parallel. If Lou Reed had been around 400 years ago, he’d have been a pal of Caravaggio, so I gave this song his sound.

A favorite painting “Sick Bacchus” is a self-portrait painted when Caravaggio was young and looking a bit peeky. This song captures the rawness of his life and the revolutionary style of his art. I gave it an industrial rock sound, because he was living a "downtown" sort of life at that time.

Listen to more of my Poisonville songs. Buy the songs on CDBaby or amazon.

Published on June 15, 2012 00:52

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, industrial-music, lou-reed, music

June 14, 2012

Meeting Caravaggio at the Cafe: Mystical Research for my Novel

In a Jerusalem café, I was drinking an espresso with Stephen Victor, an Oregon-based practitioner of a process called “family constellations.” I mentioned to him that I thought the process might be useful in my research for A Name in Blood, my historical novel about Caravaggio. Stephen agreed. Though the most common use of constellations is to resolve a family trauma that may even have occurred generations ago and been passed down to those living today, Stephen suggested that if I wanted to connect with Caravaggio about his life I should “just ask him––he’s out there.”

In a Jerusalem café, I was drinking an espresso with Stephen Victor, an Oregon-based practitioner of a process called “family constellations.” I mentioned to him that I thought the process might be useful in my research for A Name in Blood, my historical novel about Caravaggio. Stephen agreed. Though the most common use of constellations is to resolve a family trauma that may even have occurred generations ago and been passed down to those living today, Stephen suggested that if I wanted to connect with Caravaggio about his life I should “just ask him––he’s out there.”It was only a flash, but in that instant Caravaggio was sitting at Stephen’s right, opposite me. He wasn’t precisely “in a chair” next to Stephen. He was higher up, as if inset in a thought bubble. He was in the Jerusalem café, but he also appeared at the same time to be in a tavern in Rome four hundred years ago. He looked sad and yet comfortable in our presence.

Stephen knew Caravaggio was there too. He shivered violently and then shook it off with a twitch of his neck.

Subsequently I used constellations –– or more precisely I “just asked” Caravaggio and others in his life –– to feel my way deeper into the characterizations of A Name in Blood. Most particularly I found a response from Lena, the young woman who I believe was Caravaggio’s lover and who plays a central role in A Name in Blood.

As Stephen often says, this process is intellectually indefensible. So I don’t try to defend it. It happens to be what I’ve experienced, and when I’ve spoken to other creative artists, to actors and musicians, the most open ones often tell me they’ve had similar experiences or used similar techniques. Several German actors spent a night swapping constellations tales with me a year or so ago. My reading of some elliptical statements by Booker-award-winner Hilary Mantel suggests to me she may employ some similar process to achieve her astonishingly vivid characterizations.

The essence of the technique is to centre oneself in a meditative fashion. To focus one’s energy in one’s stomach, rather than in the head. The head is where we judge ourselves negatively––where we tell ourselves that this is all intellectually indefensible and we shouldn’t bother with it. In family constellations, when I’ve been open enough, I’ve felt the energy of someone else’s grandfather or someone’s fear or disease and allowed it to emerge as part of a healing process for that person. It’s the most remarkably cleansing feeling I’ve ever experienced.

Naturally I’ve heard from some people that this is nonsense. After I mentioned constellations while on a panel at a book fair, one of the other panelists, a very well-known British crime writer, joked: “I’m not channeling anyone. I’m doing all the typing.” A lady in the audience stood up to tell him that she thought his characterizations were very good and, therefore, she suspected he was employing something like the constellations technique without even knowing it.

Of course I’m doing the typing. I’m not channeling anyone or anything. Caravaggio didn’t write A Name in Blood, I did. If I was channeling him, I’d be painting, not writing, believe me.

But if you, like my British crime writer pal, think your head holds all the answers to everything, why does it choose to make life so miserable much of the time. Why does it fear an answer that might originate in some other part of the body?

In the West, there’s a tyranny of the brain, of the intellectually defensible. It’s like any of the other tyrannies we’ve embraced –– patriarchy, capitalism, monotheism. It demonizes any other way of thinking and often does so through mockery. If those systems don’t always work, they can be nipped and tucked, but don’t you even think of looking elsewhere for a better system. That’s the message at the heart of our culture of intellectual defensibility.

Personally I want my novel to be as good as it can be (and for me to be as happy as I can be). I don’t care what apparently silly things I have to do, what processes I must engage in, to get it that way. I know that A Name in Blood has been touched by Caravaggio, even if some might think that sounds daft.

Besides, the Caravaggio I met wasn’t at all the way you’d think from the writings of art historians. Their Caravaggio, as I’ve written elsewhere on this blog, was some kind of gay psycho bitch. But mine was different. I liked him. I hope you will too.

Published on June 14, 2012 02:57

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, baroque, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-crime, historical-fiction, renaissance, writing

June 12, 2012

Rescuing Caravaggio from a Bad Rap

He was a raging psycho, an uncontrollably lustful homosexual, and a bit of a bitch. Somehow he also managed to produce some of the most sensitive and innovative art ever painted, much of it clearly based on a sophisticated understanding of theology and optical science.

He was a raging psycho, an uncontrollably lustful homosexual, and a bit of a bitch. Somehow he also managed to produce some of the most sensitive and innovative art ever painted, much of it clearly based on a sophisticated understanding of theology and optical science.For many art historians and almost all creative artists writing about or otherwise depicting Caravaggio, the gay psycho bitch has predominated. But I wasn’t drawn to Caravaggio because he threw a plate of hot artichokes in an insolent waiter’s face (although I found it somehow appealing, nonetheless) or because he did a good line in paintings of little boy’s bottoms.

My Caravaggio novel A Name in Blood focuses on the most compelling aspects of his life and work. I was, after all, attracted to him in the first place because of his work, not because of the anti-establishment cult that was built around him in the ‘Sixties and ‘Seventies and which culminated in Derek Jarman’s tedious movie, where Caravaggio endlessly feeds gold coins into the mouth of a naked, sweaty Sean Bean. (After I made her watch the film, my wife told me: “Wow, I must really love you to sit through this shit.” She’s from New York; she can be bitchier than Cult Caravaggio. And yet I still give her my first drafts to read.)

It isn’t the first time I’ve found a historical novel of mine engaging in an unintended battle against long-held prejudices. In Mozart’s Last Aria, I wrote about the mysterious death of the great composer. In doing so, I discovered a Mozart who was a socially engaged intellectual and far more complex than the common perception of him –– which was finally cemented in the popular imagination by the giggling buffoon at the centre of Amadeus thirty years ago.

So too with Caravaggio. Take a look at the Caravaggio episode in Simon Schama’s The Power of Art series for the BBC. Caravaggio is shown practicing with his rapier and, later, stabbing a man to death with the aggressive drug-addled sneer of the front man of a punk ensemble. Schama wanders about Rome with no answer as to how Caravaggio found the time, talent, or spiritual intensity to paint the most vivid Madonnas in the history of art.

I won’t recount every example here of how Caravaggio deviates from the cartoon image of him. But here’s an example of the role his intellect must have played in his work. For one thing, I’m convinced by the research that shows he used a camera obscura. Not as a gimmick, but because he was a resident in the palace of Cardinal del Monte and dined with many of the great scientists of the day, conversing with them on a sophisticated level. He was able to put into practice much of the theory he heard at that table.

It’s true that Caravaggio did kill a man in a duel. He was often hauled up before the courts in Rome for brawling. He appears to have had sex with young men and female whores. Without wanting to be too relativistic, none of this was entirely without precedent among his peers, most of whom regarded his conduct with equanimity (unless they were jealous rivals.)

Most creative artists I’ve met (and this is true of myself) do not choose their field because they’re breezy, well-balanced types. Caravaggio was given to the tempestuous behavior of a man with a tendency to rage and, I think, depression. Probably this was a result of early traumas. We can’t know that for sure, because we don’t have his therapist’s notes…Or do we? A painter's canvasses are pretty close.

What we do know is that a man who made such fabulous and inspiring art deserves to be considered as more than just a hoodlum. We should approach him with our own finest parts attuned to the real Caravaggio who has so often been hidden under the stereotypical bad boy genius.

Published on June 12, 2012 02:09

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, mozart-s-last-aria, research, writing

June 11, 2012

Researching my Caravaggio novel: Learning to Kill

In the chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, I stood before the great painting now known as Seven Works of Mercy (Caravaggio called it Our Lady of Mercy.) The noise and chaos of Naples’s narrow streets spilled through the door of the chapel, just as they had in Caravaggio’s day. I wondered at the force of personality and the drive to create that enabled him to paint this phenomenal work of devotion and love, while separated by a single door from a raucous crowd in which may have lurked the men who wanted to kill him.

In the chapel of the Pio Monte della Misericordia, I stood before the great painting now known as Seven Works of Mercy (Caravaggio called it Our Lady of Mercy.) The noise and chaos of Naples’s narrow streets spilled through the door of the chapel, just as they had in Caravaggio’s day. I wondered at the force of personality and the drive to create that enabled him to paint this phenomenal work of devotion and love, while separated by a single door from a raucous crowd in which may have lurked the men who wanted to kill him.When he first went to Naples, Caravaggio had a price on his head for a fatal duel in Rome. He returned a year later unpardoned and with the additional danger of a noble Knight of Malta eager for revenge after a brawl. Caravaggio knew how to fight and, unfortunately, was at least as eager as his peers to engage in that activity (There’s no evidence that he was the homicidal nutcase portrayed in some “documentaries” and depictions of the artist. Everyone carried a sword; most were prepared to use it; Italian men were obsessed with their honour. If Caravaggio killed a man, it represented an extreme action, but not one for which most of his pals would’ve thought any worse of him.)

So Caravaggio knew how to duel, and most of my book A Name in Blood is from his point of view, thus I too had to learn how to wield a rapier.

By coincidence (in the obsessive state of researching A Name in Blood, I sometimes thought rather that it was fated), the Academy for Historical Fencing happens to be located in the town where I was born and where my parents live: Newport, South Wales. It’s a former steel town with little apparent connection to historic chivalry, yet Nick Thomas, a Medieval and Renaissance sword enthusiast, started the Academy there.

So I found myself driving up to Caerleon, the suburb where the Romans once had a fortress, on a Friday night with my Dad, ready to do battle.

The rather dandified image of dueling is over-romanticized. “You could fight like a gentleman or like a thug,” Nick said. “But it was all about killing, in the end. So it could be said that the thug predominates.”

Nick is a delightfully obsessed martial arts fan who learned Renaissance Italian so he could translate his favorite fencing manual (Ridolfo Capo Ferro’s 1610 masterpiece, the Gran Simulacro) and has won many European rapier competitions. By day he and his brother write zombie fiction (their latest is Sherlock Holmes and the Zombie Problem). With several friends, he founded the Academy in 1996. They run classes in Bristol, England, and Newport.

The Academy class gives new recruits a choice: slam each other with the medieval broadsword or run each other through with a five-feet-long rapier. Well, figuratively, at least.

In terms of the descriptive detail I picked up, my studying with Nick was invaluable. My previous fencing knowledge was drawn from contemporary epee fighting. But the rapier is very different. For a start the sword is much heavier and no one wants a drawn out bout. Things happen faster, in a single motion, rather than by building a series of moves as in epee work. Even the way you hold the sword is different.

After strapping on my chest protector and pushing down a visor tight over my big Celtic head, I discovered that I had two favorite moves. The first is simplicity itself: as the opponent thrusts, you turn your wrist up, thus deflecting his sword past your head, and at the same time you lunge at his face. The second of my favorites is pure thuggery: parry your opponent’s sword to your right, step forward with your left foot, and drive your dagger under his armpit.

While I fenced, I learned something about Caravaggio that was at least as significant, for me as a novelist, as the technical aspects of wielding a rapier. I learned about his nerve.

For a moment, when your opponent thrusts, you see the point of his sword coming right at your eyes. It takes steadiness not to watch it come on and instead to execute the parry and riposte. To do so without protective gear would surely take what the Italians call “coglioni.” I don’t think I need to translate that. It gave me a deeper degree of understanding of Caravaggio’s character that was very important in writing A Name in Blood.

Published on June 11, 2012 03:31

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, caravaggio, crime-fiction, fencing, historical-fiction, martial-arts, research

June 8, 2012

Caravaggio's Death Still a Mystery

In July 1610, Michelangelo Merisi, who is known as Caravaggio, was the most famous and controversial artist in Italy. He had killed a man in a duel and was on the run from a powerful Knight of Malta whom the latest research suggests he had injured in a brawl. Then he disappeared.

In July 1610, Michelangelo Merisi, who is known as Caravaggio, was the most famous and controversial artist in Italy. He had killed a man in a duel and was on the run from a powerful Knight of Malta whom the latest research suggests he had injured in a brawl. Then he disappeared.Most art historians have long accepted a strange and unlikely explanation for Caravaggio’s death. Caravaggio left Naples for Rome where he expected to be pardoned for the homicide in the duel and to re-enter the good graces of the Papal nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese. But when he disembarked near Rome, Caravaggio was arrested – either through treachery or mistaken identity – and his baggage sailed away with the paintings he had completed to buy his pardon. By the time he was released, he was crazed with rage, frustration and fear. He chased off after the boat up a hundred or so miles of malaria coastline, took fever, and died.

The best one can say about that is: Maybe. As a crime novelist, naturally, I like to think: Maybe not.

My long road of research for my Caravaggio novel A Name in Blood began with Peter Robb’s fabulous biography “M: The Man Who Became Caravaggio.” An Australian who lived a long time in southern Italy, Robb’s account of Caravaggio’s life is detailed in a non-academic way and deeply felt. He examines the mystery surrounding Caravaggio’s disappearance without prejudice, which earned Robb quite a deal of criticism from Caravaggio “scholars” when he published his book in 1998. Academics tend to assume that considering anything other than the hashed-over version of Caravaggio’s death represents a foray into sensationalism, rather than simple curiosity about how this most dynamic of Italian artists simply vanished.

(I encountered a similar preference for the boring and quotidian in professors writing about Mozart’s death, while I researched the composer’s mysterious end for my novel Mozart’s Last Aria. Somehow academics seem committed to taking history’s dramatic events and making them appear as banal as another day in the faculty canteen, and they get inordinately angry with someone like me who decides to eat lunch off campus.)

Vincenzo Pacelli, a University of Naples professor, is the only academic to have asserted (in an 2012 book) that Caravaggio was murdered. He’s often given the brush off, damned with faint praise, by other art historians.

Not long ago an Italian documentarian with a reputation for sensationalism claimed to have found DNA proof that Caravaggio was buried in Porto Ercole, the Tuscan town where conventional wisdom always claimed he died. That was trumpeted as the kind of astounding material the documentarian always unearthed. Whereas, in fact, it’s hardly sensational to have proven the theory of four hundred years correct.

In fact, the documentarian hadn’t proven anything. He had found the bones to have a DNA link to a few people in the town of Caravaggio believed to be related to the artist. But that kind of DNA test can prove that I’m related to a chimpanzee. Because I am, in DNA terms.

Even if Caravaggio was buried at Porto Ercole, the glee of the conventionalists in the debate over the artist’s death was false. If he was buried there, they argued, their theory was correct. Not so. If he was buried in Porto Ercole, it proves only that Caravaggio died. Somewhere. And his body ended up in Porto Ercole. How he died remains a question.

A question that a novel can resolve perhaps as well as an academic article. As a novelist I approached the question by looking at historical research--but also by delving into areas closed to academics: the emotions of the real historical characters in the novel, and my theory of why Caravaggio was so eager to return to Rome. I believe it wasn’t only for the sake of artistic prominence in the Eternal City.

Of course, to find out what I think was driving him, you’ll have to read A Name in Blood.

Published on June 08, 2012 01:23

•

Tags:

art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-crime, historical-fiction, italy, renaissance

June 7, 2012

Too Many Drugs: Following Caravaggio in Malta for A NAME IN BLOOD

I left Rome to continue my research for A Name in Blood, my Caravaggio novel which is released July 1 in the UK, in Malta. Caravaggio fled to the remote island off the coast of Africa and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. It was a strange trip for me, but the isolation and pure weirdness I felt there gave me important insights for the novel.

I left Rome to continue my research for A Name in Blood, my Caravaggio novel which is released July 1 in the UK, in Malta. Caravaggio fled to the remote island off the coast of Africa and became (briefly) a member of the Knights of Malta. It was a strange trip for me, but the isolation and pure weirdness I felt there gave me important insights for the novel.I spent December in Malta in a cheap hotel in a four-hundred-year-old building that was without heating and insulation, in a room where one of the windows didn’t close. I got sick. I took some drugs, staring across the harbor at the sheets of rain plummeting down on the Castel Sant’Angelo where Caravaggio was imprisoned for a time. It got damper in my room. I took too many drugs. I hallucinated, slept at unaccustomed hours and was awake when everyone else was in bed. I saw things that weren’t there. I drank far too many espressos at the Café Merisi, which takes Caravaggio’s family name and emblazons his face on the napkins, until I was as jittery as a June bug. A June bug with an overdose.

In this condition, I stood all day before The Beheading of Saint John, Caravaggio’s largest canvas and one of his most gruesome and disturbing. He showed John the Baptist collapsing, hands bound, on the floor of a dungeon, his executioner sawing his head away and a jailor gesturing for the severed head to be placed on a platter held by a young woman. It’s the only painting where Caravaggio signed his name. And he did it in a deep red, mingling with the blood spurting from the dying saint’s neck, giving me the title of my novel: A Name in Blood.

At night I wandered the narrow, deserted, windswept streets of Valletta’s Baroque center, weaving light-headed over the flagstones under the sad Christmas lights that rocked on the wind. Loudspeakers on the street lamps played cheesy carols. Alone as I was, I sang along, laughing to myself and feeling more than a little unhinged. In the alleys, I imagined Caravaggio here, knowing that men sought to kill him. I jogged giggling up the banks of steps that connect the streets along Valletta’s high ridges, as if I were fleeing. I panted in fear and slugged down some more drugs from the pocket of my raincoat and felt his horror of the dark.

I knew why Caravaggio had painted his figures emerging from the threatening shadows into a light so luminous that it glows straight through your skin and eyes and into the seat of your capacity for love, wherever that may be.

Stumbling down the steps toward my hotel above the gate where the Knights used to display the heads of Muslim pirates on spikes, I knew I was ready to write.

Published on June 07, 2012 01:15

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, malta, naples, research, rome

June 6, 2012

On Caravaggio’s Trail: Travelling to Research A NAME IN BLOOD

As I researched A Name in Blood, my novel of Caravaggio, I went all over Europe and North America, tracking Caravaggio's works and the places that touched his life. The period locations I visited gave me a flavour for Caravaggio’s life. In some cases, they gave me ideas for plot twists in the book.

Everywhere I found people fascinated with this most compelling of artists. On one of my sojourns in Rome, there was an exhibition devoted to Caravaggio's use of mirrors to project images (over which he painted, giving the vivid realistic feel people usually notice when they first see his work). He used his own head, probably in a convex mirror, to paint his "Medusa," which ended up in Florence at the Galleria Uffizi. The Rome exhibit made a nice mock up. Life size, as you see, though perhaps not as scary as a traveling author making a funny face.

Caravaggio lived most of his time in Rome in the palaces of wealthy patrons. For a brief period, he rented this house (right) in a tiny street in Rome's historic center. Then he fell behind on the rent, lost the place, got drunk and went around to break his landlady's windows. I stood in the tiny alley imagining what it must have been like to be Madama Bruni, with a raging nutcase hurling rocks at her shutters from a yard away and bellowing that he was going to carve her up. Unfortunately I had to cut that incident out of A Name in Blood because, as with some other juicy moments in Caravaggio’s life, they were deeply revealing, but they didn’t drive my narrative forward.

Caravaggio’s model (and, I think, lover) Lena lived here (left). In the Via dei Greci. In the heart of what used to be the Ortaccio, or Evil Garden, where only whores and the very poor lived. And artists, of course. Both places are now very expensive spots in the middle of Rome’s tourist area. But they're still redolent of C's time. At night, they're dark and empty. Though not spooky. I never get spooked in Rome. I’m too damned happy there.

Rome was an important stop on my researches into period locations (as opposed to my more farflung journeys to the many galleries housing Caravaggio’s work), but Malta was in many ways the most compelling, because Caravaggio’s influence is still so considerable. Caravaggio is an important figure for its capital, Valletta, where he became a Knight of Malta and painted one of his masterpieces, The Beheading of Saint John for the city’s cathedral. Father John Critien (right) is the only Knight of Malta who currently lives in Castle Sant'Angelo on Valletta's harbor. C was imprisoned here, and made a dramatic escape. Father John and I spent a delightful afternoon examining all the spots where Caravaggio might've been held. Many think it was in a hole in the rock called the guva.

On to Naples I went. At left is the site of the Ceriglio Tavern, where Caravaggio was attacked on his way out. He got a scar, probably just to teach him a lesson rather than an attempt to kill him, and an injury to his eye, which can be seen in his last work, David with the Head of Goliath. I noticed that for much of the afternoon anyone leaving the Ceriglio and headed toward Caravaggio's digs at what’s now called the Palazzo Cellamare would be blinded by the sunlight. A good time for an attack.

My friend Ugo Somma, far right, showed me around Naples. Here he is examining the chapel of the Knights with a fellow named Rosario who works for the Knights of Malta in Naples. At first Rosario wouldn't let us look around the Knights' church. But when I told him he looked like Caravaggio, he relented and even introduced me to his sister...

At the Knights' Priory in Naples, these fellows were hanging around in the courtyard looking like mafia capos waiting to rub someone out. A non-Neapolitan had been named that morning as the new Prior. They were, as the Italians say, "arrabiati." Mad as hell. Their sullen expressions and taciturn demeanor gave me an idea for a plot twist in A Name in Blood….

My son became an aficionado of Caravaggio as the research went on. He visited many of the galleries and churches in Rome where Caravaggio’s paintings hang. When I was painting my own versions of Caravaggio’s Madonnas, I told him the woman was named Mary. He decided we had to call his new sister by that name, which we did (in the Welsh fashion, it’s spelled Mari.) His name being Cai, we dubbed him Cairavaggio.

One of my earliest memories is of a schoolteacher who had been in Naples with the British army in World War II. He wasn’t talkative, but one day he told me about a hunchback who had beckoned him to a garden and shown him the most beautiful sight he had ever seen: the perfect view over the Bay of Naples. Somehow that simple recollection of beauty by an old man, unfolded in an uncomplicated way to a small boy, brings tears to my eyes. I found the same beauty in Naples—alongside considerable depravity, too. They say, "See Naples and die." Unfortunately for Caravaggio, that's how it worked out, quite literally. Naples is magical, lively, putrid and beautiful. From the Spanish Palace looking at San Francesco, here's one moment when I thought: Matt, you lucky fellow, isn't "research" great?

Published on June 06, 2012 04:10

•

Tags:

a-name-in-blood, art, art-history, caravaggio, crime-fiction, historical-fiction, malta, naples, rome