Adele Rickerby's Blog, page 8

August 7, 2017

Associata Catharsis- Adoption Advocacy

The President of Romania has sent a signed decree to parliament promoting some changes to the adoption law. adopției.

The adoption law, although said to be “new”, is in fact the “old” law with some minor changes. But the lack of transparency and the discriminatory nature of the law currently in force has not been changed. That law, nr.273/2004 has been very slightly modified three times since 2004: in 2009, in 2011, and in 2015. And all of that was due to pressures from society as a whole.

The modifications made by the National Authority for the Protection of the Rights of the Child and for Adoption have not really modified anything substantive, including adjustments made in April of 2015. Those adjustments really did nothing in favor of the children who find themselves “imprisoned” [apart from a permanent family] since the day that they were born.

There is really noevident hope for a permanent family for more than 23,000 institutionalized children in approximately 1500 placement centers. The new legislation really does not offer them one bit of hope.

The modifications do NOT foresee a way to truly reduce the number of institutionalized children, but rather foresees only a reduction in the time frame of adoption and also a leave time for parents to get to know the adopted child.

The modifications also allow for a subsidy of 1700 lei per month (about $425) for a time period of 1 year for one of the parents who adopt a child over the age of two years. And that’s about it.

The law continues to discriminate against children for whom a family in Romania or for whom a Romanian family cannot be found. Usually this has to do with the health of the child, the child’s ethnicity, and/or the child’s age.

The adoption law also continues to discriminate against Romanian families and non-Romanian families who live in countries that are signatories to the Hague Convention. The adoption law currently requires either Romanian citizenship, or the establishment/reestablishment of residence in Romania, i.e., to live continually in the country/territory of Romania in order to receive the evaluations and attestations necessary to adopt.

The adoption law does NOT in any way guarantee every child’s right, and particularly the right of abandoned children, to a permanent family in which to grow up.

We will protest these injustices even in the streets of Romania, and we will militate for the rights of these children.

August 5, 2017

Asociatia Catharsis Brasov- Registered Adoption Agency.

Asociatia Catharsis Brasov

From 15 to 29 July this year, together with the Directorate-General for social assistance and the protection of the rights of the child, we organised the third course of this year, to prepare families who want to adopt a child. We are glad that other 13 families of brașoveans are prepared to receive a baby from romanians in their lives.

For three weeks, the participants received detailed information about abandoned children, about abandonment issues, about the biological family, and in particular about the role of foster foster family. This time, I put the emphasis on children with hard profiles and their needs.

The theme, well-structured in three sessions, was supported by an interdisciplinary team composed of Alina Bedelean, Cathy Ross and ioana lepădatu, clementina trofin and silvia tișcă – social workers, Eva Pirvan-Szekely, lawyer. I also invited the adoptive parents, who opened their soul and shared the learners aspects of their experience.

At the same time as the theoretical knowledge of the role of a parent, which lasts three weeks, the psychological and social evaluation is also done. All these procedures take 90 days, after which the cursanții will receive the family attestation fit to adopt one or more children.

Currently in brasov, more than 100 families want to adopt a child and their number is increasing. We hope so that our efforts to provide a family of their own and permanent to an eligible child will contribute to the higher interest of abandoned children, to say mommy… Daddy… Home…

The training, and development of parental capacities this year are financially supported by our traditional partner, onlus Oikos Italia, President, Don Eugenio Battaglia.

Rate this translation

As of January 2005, when the current adoption law came into force, the number of national adoptions dropped sharply from 1.422 in 2004 to 313 in 2016, and the number of international adoptions dropped from 251 in 2004 to 2 in 2006, one in 2007, 8,, 10, 11, 12, 12 At the same time, it increased the number of abandoned children from 44.000 in 2004 to 70.000 in 2010. Irony. Although it increased the number of families qualified to adopt one or more children, there were very few national adoptions. It also increased the interest of romanians established abroad for adoption of a child. But adoption law allowed international adoption only to grandparents residing abroad. That’s just so they don’t make international adoptions! No grandfather has ever adopted an abandoned nephew, not even in Romania. In addition, adoption sets between the child and the foster family, an affectionate connection, while between grandpa and child there is already a blood link. We’ve managed, hard, very hard to replace grandparents with third-degree relatives, then four and the result of adoption was still zero. Hard, unimaginably hard to obtain the right of romanians abroad for adoption. We had to fight the legislature, because the number of romanians residing abroad was always growing. And I did. Children’s drama harassed by foster homes after growing up in foster families and the statistical data provided by the Romanian media gave us the courage to start the adoption crusade. And we’ve managed with other ngos to amend three times the articles that have made the national adoption difficult, but we haven’t yet here the international adoption-only chance for sick children in an adoption family. Still no international adoptions. The Romanian state still prefers institutionalisation instead of the foster family. The adoption law still humiliates romanians who make extraordinary efforts to adopt a child. Of the total 57.581 children, only 3250 are adoption. And 5 children were adopted international last year, although it was adoption 534. The adoption law humiliates families of romanians in the country and abroad who want to adopt, destroy dreams and kill hope. For impossible reasons, adoption law makes the lives of romanians who want to adopt the future of abandoned children. Romanian abroad are required by law, article 3, to leave her husband alone at home, to give up work and income and a comfortable life with her husband, whether it is all romanian or foreign .. The future mothers were bound by the law of adoption to live effectively and continuously 12 months in Romania, before submitting the adoption request. Many ladies got sick, depressed and gave up. The loser was the kid, and the family, and the state, but nobody cares! I asked for the repeal of article 3 that provides such nonsense. Instead of being repealed, this article has been amended, reduce to 6 months in the territory of Romania… Crazy… and a lot of other bullshit calls for adoption law three times in the last 8 years. For example: Romanians are obliged to make a statement that they have lived effectively and continuously in Romania, before submitting their adoption application!!! Another 90 days, three months, must stay in the country to Participate in the parenting class, the evaluation procedures. After, he has to stay a while to sign the psycho-Social Evaluation Report, the last document required to get the statement. Then get the certificate. And there goes the year. After obtaining the statement, families are registered in the national adoption registry, after which, there is a very long wait, which sometimes leads to even quitting. What sadness, such disappointment, only the Romans know. And all that while tens of thousands of abandoned children want a family.

July 12, 2017

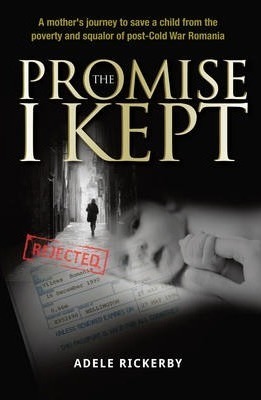

The Promise I Kept. Author; Adele Rickerby

A true story about a mother’s love.

Available from the Book Depository. Free shipping worldwide.

38%off. R.R.P of $29.99. A$18.43. You save $11.56. https://www.bookdepository.com/Promis...

Categories:

True Story Books

Adoption & Fostering

The Promise I Kept : A Mother’s Journey to Save a Child from the Poverty and Squalor of post-Cold War Romania

Paperback

By (author) Adele Rickerby

In 1991, unable to have a second child because of a medical problem and struggling to cope in a failing marriage, New Zealander Adele Rickerby decided to take her future in her hands by adopting a child from Romania. The misguided policies of the recently deposed Ceasescu government on family planning had led to the birth of an estimated 100,000 unwanted babies in that country. The Promise I Kept is Adele’s story of her nightmare journey halfway round the world to find and adopt a baby, to negotiate her way through the barriers created by red tape and corrupt officialdom and finally to carry her tiny new daughter safely home to a life where she could be properly loved and cared for.

A$18.43 A$29.99You save A$11.56

Free delivery worldwide

Available. Dispatched from the UK in 2 business days.

Adele wrote: ” You wake up one morning to the sound of history knocking loudly, impatiently, persistently at your door. To answer it is to take a leap of faith into your future”

Jonquil Graham wrote;

”A must read book for those of us who adopted from Romania, or anywhere. It’s about a mother’s perseverance and how she found conditions and the baby she adopted. It’s about hope and what happened in Romania post-Ceausescu. It is haunting and if you were in the same position, would you be brave enough to just go with your gut and do what is right for the sake of a child? ”

Costin Hewitt, a Romanian Adoptee, wrote; ” This is an amazing book. Thank you so much.”

Tony Tingle, Editor, Memoirs Publishing in the U.K wrote;

” The Promise I Kept is a powerfully and vividly written story.”

Colby Pearce, Principal Clinical Psychologist at Secure Start and author wrote;

I recently finished, The Promise I Kept, Adele Rickerby’s memoir about the personal journey that led her to adopting a child from a Romanian orphanage in the aftermath of the downfall of the Ceausescu regime. It is a well-crafted story that is accessible to most readers and can be read cover to cover in two-three hours. People will take out of the story different things, depending on their own life journey and interests. I found the insight into the inner world of the mother and evocative descriptions of the characters and places she experienced along the way most satisfying. I am happy to recommend it to the many who are fascinated by personal memoirs and accounts concerning adoption.

Sandra Flett wrote;

” I love memoirs, especially of ordinary women doing remarkable things to help others in desperate situations and this book was right down my alley. Growing up as a child and teenager in the 1980’s and 1990’s, I would hear bits and pieces about the ” Romanian Orphans”. And so to read a true story about a woman who rescues a little baby Romanian girl captivated me. I only wish it was much longer. I read it in about 2.5 hours one summer afternoon and was sad that I didn’t know the rest of the story. More please Adele Rickerby!”

1.

Kelly Proctor reviewed The Promise I Kept: A mother’s journey to save a child from the poverty and squalor of post-Cold…

A Burning Desire June 1, 2014

A Burning Desire June 1, 2014Adele Rickerby’s, The Promise I Kept, is a superb story of what the can be accomplished when one sets a goal and has the burning desire to carry one through the innumerable obstacles. Due to certain health issues, she is not able again to conceive another child. But her desire to be mother again does not die and she decides to pursue the adoption process.

Adele’s story of wanting to be mother again, despite all the immediate roadblocks that were presented to her in Australia, should had been enough to discouraged anybody from trying, but the burning desire inside her, carried her far away from the borders of this country to a land that just having been freed of a despotic ruler and was trying to find itself. Among all this chaos Adele is there, going through every and other hurdle that comes along in this journey, from mindless and corrupt bureaucracies, inhumane proposals, and much more, she is finally able to come back home with her new daughter.

This is just another great example of what the mind can conceive, it can achieve.Show Less

View on Amazon.com Add a comment View this book’s reviews on Amazon.com

2.

Kaiden reviewed The Promise I Kept

Good story! January 5, 2014

Good story! January 5, 2014An interesting story about a courageous women who singlehandedly travel on the other side of the world and struggle through a bureaucratic maze to finally achieve her dream to adopt a child. A must read for anybody who contemplate adopting a child oversea!

View on Amazon.com Add a comment View this book’s reviews on Amazon.com

3.

mark johnston reviewed The Promise I Kept

You read this from cover to cover November 27, 2013

You read this from cover to cover November 27, 2013A very interesting wee read about a young woman on a mission to the eastern block, to adopt a child. If we cast our mind back to that era it was certainly was a troubled time both politically and socially in the ‘block’. Between being thrown off trains because of her New Zealand citizenship, and not able to speak the language, she faced and conquered many problems and challenges with patience and doggedness . The corrupt ‘officialdoms’ backstreets and dangers are compensated by the sheer generosity of strangers. All these faced by a smallish woman with the burning desire for another child, despite a failing marriage at home. A very compelling read.

Share this:

Press This

Facebook87

June 3, 2017

Child Abuse in Romania

771 children died during 1966-1990 in the Romanian foster homes, IICCMER.

Posted by: Alina Grigoras Butu in SOCIAL, SOCIETY & PEOPLE

The Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and the Memory of Romanian Exile (IICCMER) has filed a denunciation to the Prosecutor’s Office for inhuman maltreatment over children admitted to foster homes during the communist regime in Romania. The case mainly refers to the sick or disabled children who used to be admitted in the hospital foster homes in Cighid, Pastraveni and Sighetu Marmatiei.

According to IICCMER for Gândul online daily, a total of 771 children died in there during 1966-1990, most of them due to medical causes that could have been prevented or treated. The IICCMER experts and legists say the cases revealed that children were submitted to inhuman treatments and aggressions. Overall, there were over 10,000 such victims in the communist foster homes.

These children used to be considered irrecoverable from the medical point of view, suffering severe handicaps, but many of them were orphans or abandoned by their parents and reached those centers without having serious diseases, IICCMER says.

One of these children abandoned in the foster home in Sighetu Marmatiei was Izidor Ruckel, now aged 37. He escaped the center after he has been adopted by an American family, right after 1990. He told his tragic story to the IICCMER experts.

“They used to beat me and another boy with a broomstick so badly that I thought I was going to die. They used to sedate us, they kept us isolated,” Izidor recounted, as quoted by Gândul.

Tagged with: CHILDREN CIGHID COMMUNIST REGIME DIED FOSTER HOMES IICCMER ORPHANS ROMANIA SIGHETU MARMATIEI THE INSTITUTE FOR THE INVESTIGATION OF COMMUNIST CRIMES AND THE MEMORY OF ROMANIAN EXILE

Inhumane Conditions; Death and Disease

771 children died during 1966-1990 in the Romanian foster homes, IICCMER.

Posted by: Alina Grigoras Butu in SOCIAL, SOCIETY & PEOPLE

The Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and the Memory of Romanian Exile (IICCMER) has filed a denunciation to the Prosecutor’s Office for inhuman maltreatment over children admitted to foster homes during the communist regime in Romania. The case mainly refers to the sick or disabled children who used to be admitted in the hospital foster homes in Cighid, Pastraveni and Sighetu Marmatiei.

According to IICCMER for Gândul online daily, a total of 771 children died in there during 1966-1990, most of them due to medical causes that could have been prevented or treated. The IICCMER experts and legists say the cases revealed that children were submitted to inhuman treatments and aggressions. Overall, there were over 10,000 such victims in the communist foster homes.

These children used to be considered irrecoverable from the medical point of view, suffering severe handicaps, but many of them were orphans or abandoned by their parents and reached those centers without having serious diseases, IICCMER says.

One of these children abandoned in the foster home in Sighetu Marmatiei was Izidor Ruckel, now aged 37. He escaped the center after he has been adopted by an American family, right after 1990. He told his tragic story to the IICCMER experts.

“They used to beat me and another boy with a broomstick so badly that I thought I was going to die. They used to sedate us, they kept us isolated,” Izidor recounted, as quoted by Gândul.

Tagged with: CHILDREN CIGHID COMMUNIST REGIME DIED FOSTER HOMES IICCMER ORPHANS ROMANIA SIGHETU MARMATIEI THE INSTITUTE FOR THE INVESTIGATION OF COMMUNIST CRIMES AND THE MEMORY OF ROMANIAN EXILE

June 2, 2017

The Stolen Generations; Healing Old Wounds

[image error]

Posted on July 28, 2015 by Adele Rickerby.

Between the 1890’s and 1970’s, Aboriginal babies and children were forcefully removed from their parents. Few records were kept, but it is estimated that between 20,000-25,000 children were stolen. These children are referred to in Australia as The Stolen Generations. By doing so, white people hoped to put an end to the so-called Aboriginal problem and put an end to Aboriginal culture within a short time frame. The Stolen Generations were taken by Governments, churches and welfare organizations. Because few records were kept of who their parents were and where they had been stolen from, many never saw their parents, relatives, or siblings again. The children were raised on missions or with foster parents. The girls were raised to be domestic servants, the boys to be stockmen. Many were physically, emotionally and sexually abused and neglected. Leaving a legacy of trauma and loss. A cycle of generational abuse and neglect has been born out of a history of racial wounds.

Forcible removal of black children from their families was part of the ideology of assimilation. Assimilation was founded on the notion of black inferiority and white supremacy, which proposed that black people should be allowed to ”die out” through a process of natural elimination. The Stolen Generations were taught to reject their culture, their names were changed and they were forbidden to speak their native language.

Healing Old Wounds.

Acknowledging the wrongs of the past as a means to healing old wounds and reconciliation.

The first National Sorry Day was held on 26th. May, 1998 and Australia holds a National Sorry Day every year.

Formal Apology

On the 13th. February, 2008, the then Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, tabled a motion in Parliament apologising to the Australian Indigenous peoples, particularly the Stolen Generations and their families and communities, for laws and policies which had ” inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on these our fellow Australians”.

The Stolen Generations/Australians Together

http://www.australianstogether.org.au/stories/detail/the-stolen-generations

Australian Law Reform Commission | ALRC

http://www.alrc.gov.au/

16. Aboriginal Customary Laws: Aboriginal Child Custody, Fostering and Adoption

An Aboriginal Child Placement Principle?

349. The Child’s Welfare as ‘Paramount Consideration’.

In general, decisions on the custody or placement of children are based on a

single undifferentiated rule, directing attention to the ‘best interests of the

child’ as the paramount consideration. The ‘paramount consideration’ applied in

all cases of child custody can be illustrated by a clause common to State and

Territory adoption legislation. The Adoption of Children Ordinance 1965 (ACT) s

15 states that: ‘For all purposes of this Part, the welfare and interests of

the child concerned shall be regarded as the paramount consideration’.[35]

This principle (commonly referred to as the ‘welfare principle’) is also

applied under the Family Law Act 1975.[36]

and in cases in State courts involving custody disputes over children. It is

also relevant to decisions on fostering and placement of children in

institutional care under State child welfare legislation (although it is not

always spelt out expressly in the legislation).

350. An Undifferentiated Criterion. There can

be little dispute that the overriding consideration in all cases of child

custody should be the welfare of the child. The problem is that the relevant

legislation usually fails to define or specify the matters to be considered in

determining this.[37]

In practice it rests with the authority involved — whether judge, magistrate,

welfare officer or public servant — to decide what constitutes the welfare of

the child. Just as the forums for considering child placements vary from State

to State, so too, we may expect, do the values and standards of the persons

applying this principle in custody decisions. The Full Family Court of

Australia has pointed out the open-ended nature of the principle:

In determining a custody application the court must regard

the welfare of the child as the paramount consideration … Each case must be

considered in the light of all the facts and circumstances particular to that

case …[38]

Advertisements

Occasionally, some of your visitors may see an advertisement here

You can hide these ads completely by upgrading to one of our paid plans.

May 29, 2017

A Mother’s Journey to Reunite Adopted Romanian Daughter With Her Roots.

This story is written by Nina Hindmarsh, Nelson Mail, Newspaper of the Year; Canon Media Awards. May 2017.

A family reunited for the first time. From left: Cristina Graham; Jonquil Graham; Cristina’s birth mother; Cristina’s birth sisters Geanina-Ionela and Maria-Magdalena.

A horse pulls a cart down a dirt road. Geese flap their way through the dust.

In a small Romanian village on the border of Moldova, 26-year-old Cristina Graham walks apprehensively with her adopted mother, Jonquil Graham. They are there, thousands of kilometres from home, to meet the woman who gave Cristina away 25 years ago.

She is small and toothless, waiting with her hands clasped tightly behind her back in front of a barren, cobb house. Next to her on crutches is her husband and Cristina’s older half-sister, Maria-Magdalena. Until now, they have never met.

Cristina hugs her birth sister first, then her birth mother. Cristina doesn’t cry, but Cristina’s birth mother sobs as she holds her tightly, swaying her back and forth.

She tells Cristina she didn’t have the conditions to care for her, that her violent husband at the time, Cristina’s father, did not like children and that her sister had pushed her to give Cristina up.

“I felt sad for her,” Cristina says later. “It was hard seeing her like that.”

After that first meeting, Cristina explores the bare neighbourhood of Bivolari that would have been her’s had she stayed in Romania.

She didn’t expect to see her birth family living like this. She is beginning to grasp what poverty really means.

Her birth family’s health is suffering due to alcoholism. There is no running water in the house, no power, and they bathe from a bucket.

Unknown

Six of the adopted Graham kids. From left to right: Tristan, Misha, Cristina, Joanna, Natasha, Masha

It is far from the idyllic childhood Cristina had being raised on a kiwifruit orchard in Golden Bay, among the loving, hustle-and-bustle of a sprawling melting-pot family.

Jonquil and her husband Bryan were one of the first New Zealand couples to attempt inter-country adoption, which included three girls from Romania. Cristina was one of them.

Together, the pair have adopted and raised nine children and fostered 20 more.

Unable to conceive children, Jonquil and Brian first became “accidental” adoptive parents when a relative could no longer care for their difficult 3-year-old daughter.

The Grahams took in the girl, and in the years following nearly 30 more children flooded into their care.

“We thought we could just love any child,” says Jonquil. “It doesn’t matter what colour or what creed. We had a big house, and we thought, ‘why not?’ Fill up the house.”

A FOUR-MONTH BATTLE

Jonquil remembers the putrid scent of boiled cabbage, urine and cleaning products as she entered a room lined with cots.

Unknown

Jonquil and Bryan Graham with their three adopted Romanian daughters. From left; Jonquil with Cristina; Bryan with Natasha and Johanna.

“What struck me was the quietness,” she says. “Babies don’t cry in there, and they don’t because nobody is going to pick them up. Their needs were not met.”

In Romania’s orphanages, babies and children were so severely neglected they had learned not to cry, because no one would answer.

Jonquil recalls the trip they took with Cristina last year as a part of TV3’s Lost and Found which aired in March. It was there that Cristina was reunited with her roots. But 25 years ago the process for inter-country adoption was full of unknowns. Bringing baby Cristina home was an arduous journey.

“It was an absolute nightmare,” Jonquil says.

It was 1989, after the overthrow and execution of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, that news began to filter out about a vast human tragedy happening to Romanian children behind closed doors.

Among the most disturbing were images of tens-of-thousands of abandoned children suffering abuse and neglect in Romania’s orphanages.

Confined to cribs, babies lay wallowing in their own filth, their cries going unheard and ignored.

There was outrage in the West. Western couples flooded in to adopt unwanted children and charities poured in to help.

Among those parents, were Bryan and Jonquil.

It was supposed to be just a three-week trip in order for Jonquil to bring their seventh child to their Golden Bay home in 1991.

“I had already been to Romania before to collect our other two Romanian twins, Johanna and Natasha,” says Jonquil. “And I was going back to adopt a boy we had left behind.”

Jonquil was haunted by the memory of two-year-old Bogdan whom she seen on that first trip but left in Romania. She was back to bring him home with her.

Jonquil left Bryan in Golden Bay in care of the kiwifruit orchard and the tribe of children.

But upon arrival, Jonquil was told the paperwork to adopt Bogdan had become invalid and she could not adopt him.

“But I always suspected foul-play,” Jonquil says. “The little boy was promised to me but I actually think they hid the papers.”

She spent the afternoon cuddling little Bogdan goodbye.

Determined not to return home empty-handed, it wasn’t long before Jonquil met Cristina-Laura.

The five-month-old baby girl had been abandoned in an orphanage by a teenage mother who did not have the resources to care for her.

But during the process of doing the paperwork, the local court threw out Cristina’s adoption application after badly translated papers stated Jonquil as being “infantile” instead of “infertile”.

Jonquil was then forced to endure three expensive and lengthy court hearings and a landmark decision in the Romanian Supreme Court involving some of the country’s most prominent lawyers in order to bring Cristina home.

She was robbed at knife point by a group of men during her stay and had her bag slashed open.

The prosecutor tried to convince the judge that the Grahams were only interested in adopting slave labour for their kiwifruit orchard and that the children would be raised for organ transplants or sold as slaves.

Jonquil appealed the case in the Supreme Court and won. She finally left Romania four months after she arrived with baby Cristina in her arms.

“I couldn’t believe I had been through that nightmare and I just wanted to get out safely and return back to my family.”

At the time of her leaving, riots were breaking out in Romania after the country’s central ruling committee decided to stop all further overseas adoptions.

Western couples who were waiting for their adoption papers to be approved panicked, creating dramatic and angry scenes. Just in the nick of time Jonquil and Cristina slipped out of Romania and into a new life.

A TRAGEDY

Among the adopted brothers and sisters that Cristina would join in Golden Bay were two Maori boys, one Rarotongan boy and a pair of Romanian twins.

A second pair of twins from Russia, a girl and boy, would join the family a few years later.

Their historic house sits at the base of Takaka Hill and is much quieter than it once was.

All but one of their nine children have left home, although grandchildren keep spilling through the doors now.

Jonquil says the most remarkable part of the trip back to Romania to meet Cristina’s family was finding out that their Romanian twins, Natasha and Johanna’s birth family, lived just streets away from Cristina’s birth family.

“I was absolutely gobsmacked,” she says.

Jonquil and Bryan had bought the tiny malnourished twins back from Romania when they were 10-months-old.

But in 2009, tragedy struck the devoted parents.

One of the twins, 19-year-old Natasha, was hit by a car in Nelson and died of her head injuries months later.

As the TV3 crew were filming on the street outside Cristina’s birth mother’s home, the twins’ own birth mother had been watching from across the road. She recognised Jonquil. She walked up to their interpreter to say: “When is that lady bringing the twins back to see me?”

The interpreter had to tell her that one of the mother’s daughters had died.

“It was so hard,” says Jonquil. “How do you tell a mother their child is dead?”

They returned a few days later with albums of the twins’ life to show the birth mother.

The last page of the album showed a photo of Natasha’s headstone.

“It was very emotional,” says Jonquil quietly. “I wish I would have had the language to tell her about the kilometre-long line of cars at her funeral.”

A NEW HOME

Jonquil says that although most of the couple’s adopted children have left home they still seem to keep adopting people.

“We have kind-of taken on the half-sister, Maria-Magdalena because she needs a family and we want to help her kids,” says Jonquil. “Now I will make a greater effort to learn Romanian.”

The Grahams say they are still in daily contact with her.

“She didn’t have the good start like Cristina. She’s a solo mother and doesn’t have much to do with her own mother.”

Jonquil says everyone is special and often they can’t help their circumstances, like those who are not loved properly.

“But that happens to millions of youngsters in the world, sadly. Everyone wants a rock.”

Cristina lives in Christchurch now, a solo-mother with a daughter of her own.

She has stayed in daily contact with her birth sisters by Facebook, but has struggled to keep the communication up with her birth mother.

Jonquil says a lifetime of questions for her have been answered for Cristina.

“It was a real eye-opener for Cristina. She is more settled now somehow, more at home in herself,” she says.

“I think she finally understands now why she was given the chance at a better life.”

Jonquil Graham is the author of the book, How Many Planes to Get Me? A story of adopting nine children and fostering 20 more.

– Stuff

May 18, 2017

Alex Kuch; A Voice of Hope

It is a tough old world we live in. There is a lot that you can take away from abandoned orphans, but you can’t take away their hope.

Alex Kuch has been selected to attend the Global Changemakers Forum in Switzerland in July, 2017. Over 4,000 young people applied to attend. Alex was one of only sixty chosen.

Posted on February 18, 2015 by adelerickerby

[image error]Alex Kuch, a well known former Romanian orphan, is to meet with Romanian Officials to discuss the Reopening of International Adoptions.

Whangaparoa, March 14, 2015, Former Romanian Orphan Alexander Kuch, a New Zealand well known adoptee will be travelling to Romanian in March. Alex will be speaking to Romanian Officials to discuss the Reopening of International Adoptions, which have been closed since 2003. Additionally he will be engaging in speaking Engagements in Brasov and where everything started for him in his birth town Cluj-Napoca. Alexander Kuch was adopted from Romania by German parents and lived for 12 years in Germany and now for 8 years in New Zealand. Since 2003 International Adoptions have been closed in Romania and since then Alex has been urging the Romanian Government to Reopen Adoptions. Two years ago he was invited to travel to Romania to speak to the Romanian Government about the reopening of the International Adoptions. The topics that Alex will be addressing in Romania are: What is necessary for that Romania Reopens International Adoptions? What New Zealand can do to help with the Reopening of International Adoptions and the rest of the International community? What can be done together to improve the quality of life for a proportion of orphans in certain institutions? Izidor Ruckel, the well-known author (“Abandoned for Life”) and ‘Emmy’ award recipient, who was adopted by American parents in 1991, will also be speaking.” We hope that our testimonies will help not only to reopen the International Adoptions, but also change the terrible conditions in the orphanages, ” said Alex. Additional Media links of his last trip: New Zealand Media Interview , His Parliamentary address & News Paper Article Alexander Kuch A quote by him “I personally believe there is hope for Romania especially for the 70 thousand orphans as hope is only possible in a time of crisis and like in the 1990’s there is hope now” ~ Alexander Kuch ~

A Time For Hope

Posted on February 18, 2015 by adelerickerby

[image error]Alex Kuch, a well known former Romanian orphan, is to meet with Romanian Officials to discuss the Reopening of International Adoptions. Whangaparoa, March 14, 2015, Former Romanian Orphan Alexander Kuch, a New Zealand well known adoptee will be travelling to Romanian in March. Alex will be speaking to Romanian Officials to discuss the Reopening of International Adoptions, which have been closed since 2003. Additionally he will be engaging in speaking Engagements in Brasov and where everything started for him in his birth town Cluj-Napoca. Alexander Kuch was adopted from Romania by German parents and lived for 12 years in Germany and now for 8 years in New Zealand. Since 2003 International Adoptions have been closed in Romania and since then Alex has been urging the Romanian Government to Reopen Adoptions. Two years ago he was invited to travel to Romania to speak to the Romanian Government about the reopening of the International Adoptions. The topics that Alex will be addressing in Romania are: What is necessary for that Romania Reopens International Adoptions? What New Zealand can do to help with the Reopening of International Adoptions and the rest of the International community? What can be done together to improve the quality of life for a proportion of orphans in certain institutions? Izidor Ruckel, the well-known author (“Abandoned for Life”) and ‘Emmy’ award recipient, who was adopted by American parents in 1991, will also be speaking.” We hope that our testimonies will help not only to reopen the International Adoptions, but also change the terrible conditions in the orphanages, ” said Alex. Additional Media links of his last trip: New Zealand Media Interview , His Parliamentary address & News Paper Article Alexander Kuch A quote by him “I personally believe there is hope for Romania especially for the 70 thousand orphans as hope is only possible in a time of crisis and like in the 1990’s there is hope now” ~ Alexander Kuch ~

May 4, 2017

Romania’s Institutions For Abandoned Children Cause Life-Long Damage

Posted on February 6, 2016 by adelerickerby

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

Romania’s institutions have a history of neglect, physical, sexual and emotional abuse which still continues to this day and causes emotional, physical, and mental scars.

Institutionalized care, according to Dr. Victor Groza, the Grace F. Brody Professor of Parent-Child Studies at the Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, causes problems with developmental, physical, psychological, social and brain health. Dr. Groza stated, “The regimentation and ritualization of institutional life do not provide children with the quality of life, or the experiences they need to be healthy, happy, fully functioning adults.” They are also unable to form strong and lasting relationships with adults, leading to severe problems with socialization, primarily building trust and lasting relationships amongst adults and children alike.

This article, kindly provided by Dr. Victor Groza, is an easy to follow guide to the risks inherent to children institutionalised at an early age. Dr. Groza has been developing social work education and promoting best practices in child welfare and domestic adoptions in Romania, since 1991.

Victor Groza; PhD,LISW-S Grace F. Brody Professor of Parent-Child Studies, Director; Child Welfare Fellows Program Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio.http://msass.case.edu/faculty/vgroza/ – Faculty website for further reading.

https://www.facebook.com/adoptionpartners/?fref=ts – Website about Professor Groza’s post-adoption practice.