Adele Rickerby's Blog, page 6

February 20, 2018

Shame of a Nation

Don Lothrop

26.10.2017

Izidor Ruckel was born in 1980. When he was six months old, he became ill and his parents took him to a hospital where he contracted polio from an infected syringe. Later, the hospital doctors encouraged his parents to drop him off at an orphanage. From 1983 until 1991, Izidor lived in the Sighetu Marmatiei orphanage.

No one knows how many children were in Romanian orphanages at end of communism. The number is estimated to have been somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000. What we do know is that child abandonment was actually encouraged by the Romanian government as a means of population growth by discarding children who could not be productive workers for the state.

Sighetu Marmatiei is located in Sighet, a small city in northern Romania. It is the hometown of Holocaust survivor and Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel.

The Sighetu Marmatiei institution is located on the western edge of town behind a 6-foot wall. The sign above the entry reads “Camin Spital Pentru Minori Deficient,” which translates to the “Hospital Home for Deficient Children.”

In 1990, shortly after communism fell, ABC News’ 20/20 producer Janice Tomlin visited Sighet and produced the awarding series “Shame of a Nation.” Tomlin’s photos and videos brought the world’s attention to Romania’s horrific child welfare practices.

Communist newspaper encourages Mothers to leave their children in State Care

Communist newspaper encourages Mothers to leave their children in State CareDan and Marlys Ruckel of San Diego watched the 20/20 broadcast and went to Romania with the intention of adopting a child. On October 29, 1991, Dan and Marlys adopted Izidor. He was one of many Sighet orphans to make San Diego their new home.

In 2016, Izidor moved back to Romania, where he has committed his life to children without families and finding the means to support the 60,000 orphans of his generation who were never adopted.

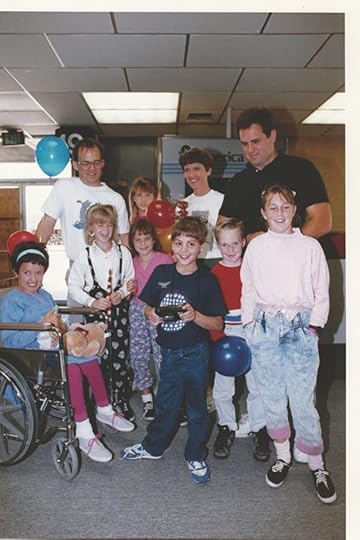

Izidor meets his new mother

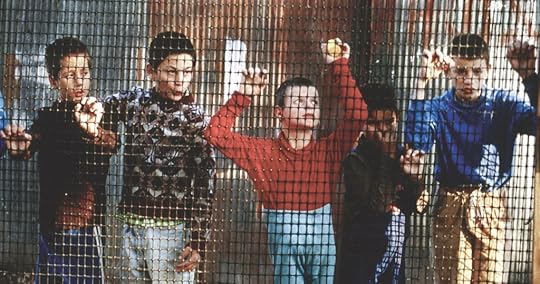

Izidor meets his new mother 1990 – Izidor behind orphanage bars

1990 – Izidor behind orphanage bars Izidor’s family

Izidor’s familyI recently met Izidor at the Cluj train station to talk about his life, why he moved back to Romania, and the current state of child welfare.

TELL ME A LITTLE ABOUT YOUR BACKGROUND

From 3 until 11, I was in a hospital for children, not an orphanage. But back then, and still today, there is no difference between how a kid is treated in a children’s hospital or a state orphanage. They are both institutions.

Two years after arriving in the US, I started to miss the institution in Sighet. Nobody in the US had the answers that I was looking for, and I took out my anger on the people that loved me most, my adopted family. I was a child from hell.

Then a Romanian family came to San Diego for Easter and I heard about Christ. I wrote down tons of questions and began to find the answers I was searching for. People ask me how I overcame this. It isn’t because of my parents or anything I did, it was because I allowed Christ to tell me who I really was.

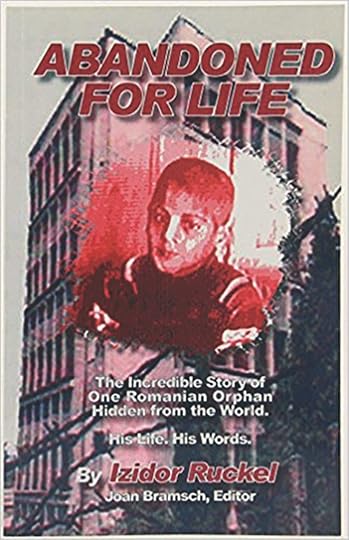

As my anger subsided and family life improved, I was asked to write a book to help families who adopt abandoned children. The book, Abandoned for Life, was published in 2003 and sold over 30,000 copies.

Izidor in the US with his father

Izidor in the US with his fatherFor 17 years, since 2001, my primary life goal has been to tell people what happened in my institution and make sure it stops happening to other children in Romania. I have spoken hundreds of times, including on the BBC, in the Washington Post and recently in an interview with Morgan Freeman that will be aired this October in 176 countries on National Geographic.

DESCRIBE LIFE IN THE ORPHANAGE

We woke up at 5, stripped naked, since most kids wet themselves in bed, and went to another room for new clothes while the floor was cleaned. We ate breakfast, washed up and were put into a clean room where we just sat there rocking back and forth, hitting each other, sleeping or watching someone cry until they were drugged. After lunchtime, we went back into the clean room, repeating the same things as the morning. Then we were fed, bathed again, put into clean clothes and into bed for the night.

WHAT DO YOU WANT THE WORLD TO KNOW ABOUT YOUR EXPERIENCE?

First, that the children suffered more than anyone knows. No reporter can capture the suffering. The abuse was worse than anything reported. If you were handicapped like me, you were hidden and never allowed outside the institution.

Secondly, despite all trauma and emotional wounds, no life is ever lost. If we give these kids, now adults, some opportunity, with love, nourishment and development, they can function in the world and develop independence. I stay in touch with the kids I grew up with and they can be helped. They still have dreams.

WHY DO YOU KEEP RETURNING TO SIGHET ?

There are many reasons. First off, it was my home for 11 years and believe it or not, there are memories I cherish. The few times I was allowed out of the institution, I was in awe of the natural beauty of Sighet. Romania to me was the beautiful land outside the institution, not the evil inside the institution.

I like to visit some of the nurses. I call them my seven angels. Their love and compassion was the only source of hope I had.

There is also a specific memory that reminds me that God was with me even though I did not know who He was. On one of my trips outside the institution, I saw a dead man hanging on a cross. The nurse said it was Jesus Christ, but without any explanation. I actually thought he was some poor guy from Sighet.

I kept feeling sorry for him when I got back to the institution. Now I take a picture of that cross every time I am back in Sighet.

I go back to reconnect with the kids I grew up with. In 2014, four of us went back to the institution. Dolls, furniture and clothes were lying around like it just closed. Crows were everywhere like in a haunted house. But it was remarkable that each of us remembered things that the others had forgotten. It felt really good for us to share our common experience. When I asked them if they missed this place, we all said ‘yes’. It was our only childhood home.

But the biggest reason is to find out what really happened there. Even though the place had been closed for 11 years, it is still filled with records and supplies. When I was seven, a kid named Duma was beaten so badly that I hid under the sheets, fearful that I might be next. In the morning, I saw Duma’s naked bruised body and by lunch he was dead. Last year I found his medical records. His official cause of death was “stopped breathing.”

There was another kid named Marian who was hyperactive and was often given medicine. His father visited him every weekend and I would jealously look out the window as they sat on a bench. In time, Marius stopped eating and lost the will to live. I remember looking out the window on the Sunday when he died in his Dad’s arms. His Dad was crying and praying to heaven.

In 1995, there was a media story that Romanian orphans were given rat poison. Three years ago, a nurse from institution confirmed that Marius and many other kids were given rat poison.

Many former orphans are returning to Romania for answers. For me, it is all about forgiveness and making sure Romania stops sweeping the child welfare issue under the carpet. Children’s rights and interests are still being ignored.

From left to right: historian Mia Jinga, Izidor Ruckel and the director of IICCMER, Radu Preda. Photo: Lucian Muntean

From left to right: historian Mia Jinga, Izidor Ruckel and the director of IICCMER, Radu Preda. Photo: Lucian MunteanOn June 1, 2017, the state-funded Investigation of Communist Crimes (ICCMER) submitted a criminal complaint to the Ministry of Justice for the deaths of 771 children in the Sighetu Marmatei, Cighid and Pastraveni orphanages between 1966 and 1990. Investigators say this is just the tip of the iceberg for a much wider investigation that is needed into Romania’s 26 orphanages.

ICCMER investigators and archivists say official records list pneumonia and brain disease as the main causes of deaths, but witnesses say the causes were exposure to the cold, poor hygiene, starvation, lack of healthcare, rat poison, and violent physical abuse.

Investigators say Communist records classified children into 3 categories: reversible, partially reversible and non- reversible. Children in the latter two categories were thrown into centers to die.

Radu Preda, director of ICCMER says “My plea as a father is to ensure that these things never happen again. Let us do something on the media level and at the institutional level in order to ensure that no child in this country who has a handicap, or illness, or has been abandoned will ever be slapped, starved, tied down or left to die in their own feces.

We need to acknowledge the utterly uncivilized society of our communist past and rid all traces of this sickness from our child protection system.”

TELL ME ABOUT THE CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION YOU ARE A PART OF?

I agreed to help bring attention to a criminal investigation led by the Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes (ICCMER). This investigation focuses on the deaths of children in Sighet Marmatiei and two other institutions.

I asked the investigators if they were going after nurses and they said “No, only the people who dispensed medicine and managed the facilities.” Once I knew that, it was okay with me.

But I am less interested in putting people in jail than I am interested in getting financial resources from the State to support the 60,000 orphans of my generation that were never adopted. Most of them have no means to support themselves as adults and are homeless. My hope is that this investigation will lead to a much larger class action suit on behalf of these 60,000 citizens. There needs to be a cost for gross neglect or things will not change.

TELL ME ABOUT HOW THE ROMANIAN MEDIA COVERS CHILD ABUSE AND WELFARE

I could not believe all the Romanian media at the June 1st press conference announcing the criminal investigation. This was history! Romanians finally fighting for something that we failed to do all these years. I always challenge the Romanian media since all of the stories on orphans and child abuse come from international news organizations. Even today, all the footage of child neglect comes from international organizations.

For years people were embarrassed and scared about this issue. But now it seems young people are waking up to the fact that this is still going on.

IS THERE STILL ABUSE IN ROMANIA INSTITUTIONS

Yes there is. I do not know from firsthand experience, but I have heard so from people I know and trust. I am trying to get access to more institutions to help kids and social workers. I am not living in Romania to embarrass or destroy people. But the government officials in Parliament seem to have no clue what is really happening in their institutions.

DO YOU THINK ROMANIA SHOULD OPEN INTERNATIONAL ADOPTION?

I am fighting for international adoption for children with special needs or those that have no chance of being adopted in Romania. Most of the people in the government reject this idea on the basis that children will be damaged by losing their culture and identity if they get adopted outside of Romania.

That’s a horrible excuse. From the moment these children enter the institution they are stripped of everything. Their dignity, freedom and their brains become mush. Tell me, what culture are they losing by being adopted abroad?

The issue in Romania today is all about money and jobs for political patronage. The State pays institutions, residential homes and foster care a stipend for each child. If the State found adoptive families for 20,000 of the 60,000 children in State custody, they would lose 33% of their funding and the jobs they often give to family and friends.

In my generation, the government wanted to dispose of the children. Today, they want to profit from them.

WHAT BOTHERS YOU THE MOST ABOUT THE CHILDCARE SYSTEM TODAY?

I am actually impressed with how many good social workers want to change the system. I get lots of emails from social workers and was shocked to see how many social workers showed up at the Romania Without Orphans conference last November. It is a great joy to see all of the Romanian families that have adopted and want to adopt.

We all know that institutions are not the answer. But I am not in favor of just shutting down the institutions. Simply putting kids on the streets is even worse. At least institutions provide a bed, food, clothing and shelter. Our train stations are filled with homeless.

The biggest problem we have today is that the workers who worked in the institutions in the 1980’s through the mid-1990’s still work in the system. You can’t expect change by renovating buildings when you have the same people and same culture.

I visited 6 orphanages 2 years ago. Most of the kids saw my story on television and were comfortable talking to me. I asked each child, “Do you like living here?” They said “See that lady over there? She still beats us.” I asked “how long she has been working here?” They said “from day one, since this place opened.”

It is constantly the same response. And I thought “Wow, there is the problem.” These people need to be replaced.

I want to work with the system. I want to stay in Romania. I can see that people are really looking for answers. I am getting a powerful response when I speak to the new generation of Romanians. I believe the time is right to confront our past and create a system that works in the interests of children.

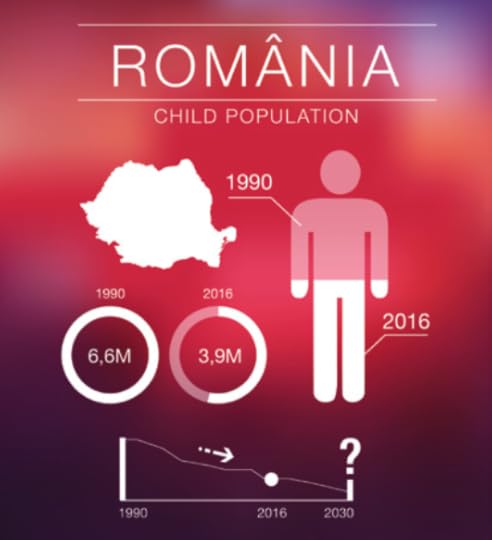

The massive decline in child population is the greatest threat to Romania’s future

The massive decline in child population is the greatest threat to Romania’s futureAUTHOR’S CONCLUSION

I was moved by Izidor. He travels around Romania on filthy trains. He carries his suitcase without complaint, despite a partially paralyzed leg. He does not have much money and is not motivated by fame or public attention. What he has is a passion and purpose.

Romania in 2017 reminds me of growing up in Germany in the 1970’s. I remember talking to my German teenage friends about Nazism and the Holocaust. They had no answers, no ability to comprehend the horror, just a deep passion to fight any legacy of Nazism. I feel the same sentiment among young Romanians today as they feel deep anger towards any abuse or injustice towards children.

It is cliché to say that our future is in our children. But in Romania the numbers speak for themselves.

Every decision made in our homes, communities and government, needs to be made in the context of “Is this a good place to raise healthy children and are we doing our best to find every child a loving family?”

Izidor is in desperate need of a new leg-brace for his polio damaged leg. Please see the link and share or donate if you can.

Thank you for your support

https://www.youcaring.com/izidorruckel-905158

Share this:

Press This

Facebook112

https://widgets.wp.com/likes/index.html?ver=20180212#blog_id=76011995&post_id=1568&origin=thepromisekept.wordpress.com&obj_id=76011995-1568-5a8be5e33909d

February 18, 2018

Foștii copii instituționalizați din România se reunesc pentru a investiga abuzurile orfelinatelor lui Ceaușescu Postat pe 6 mai 2015 de către ChildPact în Știri de la ChildPact

Mirela Oprea, secretar general al Pactului Copilului și membru de onoare al rețelei Federeii, a declarat în cadrul evenimentului de lansare a asociației că o astfel de structură este necesară pentru că trauma acestor copii instituționalizați persistă încă în societatea românească. "Investigăm situația foștilor prizonieri politici și a abuzatorilor lor, dar încă nu am început să vorbim despre cei care au exploatat copiii în orfelinate și nu ne-am ocupat încă de ceea ce aceste victime au devenit astăzi", a spus Mirela Oprea.

Ea a subliniat că atît societatea civilă, cît și foștii copii instituționalizați au ajuns acum la o vârstă de maturitate, permițându-le să coopereze împreună. Această colaborare între avocații și foștii victime-copil este următorul pas logic necesar pentru avansarea în continuare a protecției copilului în România. "Nu știm câți dintre adulții de astăzi au avut experiența de instituționalizare în copilărie pentru că nu au voce în societate", a explicat Mirela Oprea. Scopul rețelei Federeii este de a ajuta pe cei care au experimentat instituționalizarea comunistă în copilărie să devină o societate vocală. "Vrem să sprijinim crearea unei anchete prezidențiale parlamentare care să investigheze toate aceste abuzuri. De asemenea, dorim să sprijinim pe toți cei care se confruntă încă cu cicatricile trecutului, oferindu-le servicii care le-ar ajuta în reconstrucția identității lor și schimbând percepția lor cu privire la instituționalizare ", a adăugat Mirela Oprea.

Până în prezent, nimeni nu știe numărul exact de persoane care au petrecut o parte din copilărie în orfelinatele copilului. Din manifestarea rețelei reiese că "în ciuda investițiilor masive făcute pentru sistemul de protecție a copilului, nici o guvernare postcomunistă nu a efectuat o cercetare pentru a afla numărul copiilor instituționalizați, dar putem estima că cifrele sunt în jur de câteva sute de mii. În 1989, în așa-numitele orfelinate românești, erau circa 100.000 de copii instituționalizați. Mulți dintre noi au făcut parte din acești copii, trăind în condiții atât de mizerabile încât au devenit subiectul a numeroase emisiuni internaționale ", explică manifestarea lui Federeii.

Efectele instituționalizării sunt devastatoare pentru dezvoltarea copiilor pe termen lung. Acești copii au trecut prin situații umilitoare în timpul și după instituționalizare. "Nu am fost, totuși, unul dintre regulile sociale de bază în timpul petrecut în orfelinate. Prin urmare, odată ce am părăsit instituțiile, majoritatea dintre noi nu s-au putut asigura o viață decentă, având dificultăți în găsirea unui loc de muncă sau o casă și au trebuit să facă orice pentru a-și câștiga plecarea. În consecință, în sistemul penitenciar românesc, adulții care au experimentat instituționalizarea în copilărie sunt suprareprezentați. Mulți dintre noi ascund de familiile și prietenii lor faptul că au fost crescuți în orfelinate. Multi dintre ei isi cauta in continuare familiile lor biologice sau inca se lupta cu consecintele emotionale si fizice ale vietii in orfelinate ".

Președintele Federeii, Daniel Rucăreanu, a explicat că a planificat acest proiect din 2013, când a început să caute oameni care au trecut printr-o experiență similară cu el. Rucăreanu a explicat că majoritatea adulților instituționalizați în copilărie sunt marcați de timpul petrecut în orfelinate.

Vicepreședintele Federeii, actorul Costel Cașcaval, a subliniat că, spre deosebire de prizonierii comunisti care erau maturi și știau de ce au fost închiși, copiii de 4 ani care au fost instituționalizați nu aveau idee de ce au fost trimiși în orfelinate, nici cum să se apere. Cu toate acestea, o mare parte din discursul public a fost adresat prizonierilor politici din România și nu sa spus nimic despre copiii abuzați de la orfelinate. El a reamintit că în timpul regimului comunist, toate cazurile de furt sau de efracție pe care poliția nu le-a putut rezolva au fost atribuite copiilor care au scăpat din orfelinate. Acestea au fost apoi cătușe și pedepsite în fața tuturor celorlalți copii.

Secretarul general al rețelei, Vișinel Bǎlan, a menționat cum își amintea totuși bătăile primite pentru că nu știa cum să conta până la zece ani sau cum a sărit de pe podea pentru a fugi de la orfelinat după ce a fost bătut din nou sau cum a fost violată în aceeași noapte în gară.

Inițiatorii proiectului au menționat că doresc să facă un muzeu care să reamintească orfelinatele regimului comunist român, unde vor fi prezentate fotografiile, videoclipurile, documentele și obiectele copiilor din acea perioadă. Primul pas al acestui proiect este găzduirea unui muzeu virtual pe site-ul rețelei.

Orice persoană care poate dovedi că a fost instituționalizată de cel puțin o zi în copilărie poate deveni membru al rețelei Federeii. De asemenea, prieteni, familii și orice alte persoane interesate pot deveni observatori în cadrul asociației. Asociații precum "Federeii" există în Marea Britanie, Australia, Kenya, SUA. România ar putea fi o sursă de inspirație pentru regiunea noastră, iar modelul Federeii ar putea fi urmat de țări precum Moldova, Serbia, Albania, Armenia și Georgia.

Mai multe fotografii ale evenimentului de lansare disponibil aici.

February 5, 2018

Associatia Catharsis-Copii Adoptati Orfani Abandonati

[image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error] [image error]

Copilul, cel mai preţios dar

6 Photos · Updated about a month ago

2017 a fost cel mai generos an pentru 39 de copii abandonaţi, aflaţi pe lista copiilor cu profil greu adoptabili. După schimbarea legii adopţiei, iunie 2004, numărul copiilor adoptaţi naţional a scăzut de la 1422 în 2004 la 313 în 2016. Şi mai grav, de la 251 copii adoptaţi în 2004, numai doi copii au fost adoptaţi internaţional, apoi, zero adopţii internaţionale în anii 2006…. 2012 şi doar cinci în anul 2016. În schimb, a crescut numărul copiilor abandonaţi, de la 44.000 în 2004, la 70.000 în 2010. Atunci am lansat campania ”Vrem o Românie fără orfani” ! Am reuşit împreună cu alte ONG -uri să modificăm de trei ori această lege, respectiv, articolele care au îngreunat adopţia naţională timp de 12 ani şi au făcut imposibilă adopţia internaţională. Este greu, este imposiobil de înţeles, motivul pentru care Guvernele Tăriceanu, Boc şi Ponta au respins ideea redeschiderii adopţiei internaţionale. Zeci de mii de copii au fost condamnaţi la o viaţă fără familie, fiind hărţuiţi prin centre de plasament sau spitale, în loc să fie daţi în adopţie internaţională. Din cauza stării de sănătate, a vârstei şi a etniei copiii abandonaţi de ieri şi de azi sunt adulţi asistaţi social, cei mai mulţi marginalizaţi, în risc de excluziune socială. Am luptat ani de zile cu autorităţile centrale şi greu, foarte greu am reuşit să îndreptăm greşelile celor care decid destinele orfanilor români. Începând din 2016 am reuşit să schimbăm mentalităţi şi atitudini în rândul familiilor care vor să adopte un copil şi iată, împreună dăruim copiilor un cămin, o familie, un viitor în siguranţă. Schimbăm destine şi mentalităţi care se aflau pe lista copiilor cu profil greu adoptabili. Ne-a adus zâmbete şi multă bucurie!

January 16, 2018

The Romanian Federation of Non-governmental Organisations; 51% of Romania’s Children Lives in Poverty

Posted on June 16, 2016 by ChildPact in News from our members, Romania // 0 Comments

Photography: Silviu Ghetie

Photography: Silviu GhetieSource: The Romanian Federation of Non-governmental Organizations (FONPC)

The Romanian Federation of Non-governmental Organizations writes an open letter to draw attention to the importance of the Children’s Ombudsman in Romania, an institution that would guarantee effective protection for the rights of the child.

Dear Mr. President of Romania, Klaus Iohannis,

Dear Mr. President of the Senate, Călin Popescu Tăriceanu,

Dear Mr. President of the Juristic Commission on appointmens, discipline, immunity and validations from the Senate of Romania, Cătălin Boboc

Dear Mrs. President of the Commission for human rights and minorities,

The number of children in Romania is drastically decreasing: on the 1st of January, 2016, the number of children was 3976,5, 23,4 thousand lower compared to the previous year. Amongst these children 51% live in poverty and only one in 3 disadvantaged children finish middle school, 57.279 children in the social protection system, over 44 thousand of primary school age and over 48 thousand children or middle school are found outside the education system, over 2.700 children with severe disabilities aged between 7 and 10 do not go to school, 2 children on average are victims of some form of abuse every hour by over 20.000 children, amongst who 15.000 have been condemned.

The Federation of Child Protection NGOs FONPC, a common voice of 87 active organisations in the domain of welfare and protection of children draws attention to the importance of the Children’s Ombudsman in Romania as an institution that would guarantee effective protection for the rights of the child.

The UN Convention for the Rights of the Child, an international convention signed and ratified by Romania back in 1990 which set the foundation for the country’s child protection reform starting in 1997 mentions in its Article 3, Al. 1: “The interests of the child will prevail in all actions that affect children, undertaken by the public or private social work institutions, by the judiciary bodies, administrative authorities or legislative organs”. Given the fact that we are referring to the future of our country and the rights of a vulnerable category of individuals, the rights of children must be prioritized in Romania.

In this context, we ask you to support the establishment of a Children’s Ombudsman institution in Romania, guaranteeing verification and monitoring mechanisms for the implementation of the UNCRC requirements regarding the rights of the child and that would protect the superior interest of the child, even from state abuse at times.

The legislative proposal to establish the Children’s Ombudsman institution as an autonomous public authority, independent from any other public authority, which governs the respect for children’s rights as defined in the Romanian Constitution, the UNCRC and other legal provisions, can be found in Romania’s Senate.

According to ENOC standards, the Children’s Ombudsman institution has attributions and missions that exceed the sphere of competence of the current People’s Ombudsman, which is why Romania lacks other adequate structures that fully correspond to the function of monitoring the rights and protection of children against violence, neglect, abuse and exploitation, as well as against social exclusion and discrimination.

In support for this proceeding for the establishment of a Romanian Children’s Ombudsman we recall the recommendations of the UN Committee for the Rights of the Child addressed to Romania back in 2009, from which we quote the following:

“13. […] The Committee expresses its concern regarding the fact that the People’s Lawyer does not meet the criteria established in the Paris Principles and notes that the existence of this institution is not very well known. Consequently, this receives a reduced number of complaints with regards to children, a number that has been declining compared to the total number of complaints made. The Committee notes with concern that the Parliament’s rejection of a normative act project through which the desire to establish the Children’s Lawyer institution was expressed.”

“14. The Committee recommends that, keeping its general commentary nr.2 (2002) with regards to the role of independent national institutions for the protection of human rights from the domain of promoting and protecting children’s rights, but also its previous recommendations, the state party ought to revise the statute and efficiency of the People’s Lawyer institution in the domain of the promotion and protection of children’s rights, equally taking into consideration the criteria retrieved in the Paris Principles. This body has to benefit from all human and financial resources necessary for fulfilling its mandate in an effective and significant manner, especially in terms of capacity to receive and examine complaints from/on behalf of children related to the violation of their rights.

The Committee recommends that, in accordance with the previous recommendations, the state party continues to invest effort into the creation of an independent Children’s Lawyer institution”.

In the report finalized following Romania’s visit back in 2015, UN Rapporteur Philip Alston claimed that there is a need for a Children’s Commissary-type institution, a body that would have a clear mandate and the power to protect the rights of children, whilst also benefiting from adequate resources to promote and protect the rights of the child, as well as independence. At the European level the Child’s Ombudsman or the Commissioner for the Rights of the Child are identical institutions, with names varying from country to country.

The Federation of Non-governmental Child Organizations has been advocating for the establishment of the Children’s Ombudsman institution in Romania for more than 10 years.

We strongly believe that you will support the Children’s Ombudsman and the creation of an independent mechanism for the monitoring of child’s rights which will guarantee respect for all children’s rights and will protect them from abuse of all kinds.

With kindest regards,

Bogdan Simion

FONPC President

Daniela Gheorghe

FONPC Executive Director

January 14, 2018

December 13, 2017

Rușinea unei națiuni Apăsați One – Don Lothrop

26.10.2017

Izidor Ruckel sa născut în 1980. Când avea șase luni, sa îmbolnăvit și părinții lui l-au dus într-un spital unde a contractat poliomielita de la o seringă infectată. Ulterior, medicii spitalului i-au încurajat pe părinții săi să renunțe la un orfelinat. Din 1983 până în 1991, Izidor a trăit în orfelinatul Sighetu Marmației.

Nimeni nu știe câte copii se aflau în orfelinatele din România la sfârșitul comunismului. Numărul este estimat a fi undeva între 100.000 și 200.000. Ceea ce știm este că abandonul copiilor a fost încurajat de guvernul român ca un mijloc de creștere a populației prin aruncarea înapoi a copiilor care nu puteau fi productivi pentru stat.

Sighetu Marmației este situat în Sighet, un mic oraș din nordul României. Este orașul natal al supraviețuitorului Holocaustului și al câștigătorului premiului Nobel, Elie Wiesel.

Instituția Sighetu Marmației este situată la marginea de vest a orașului, în spatele unui perete de 6 metri. Semnul de deasupra introducerii citește "Camin Spital Pentru Minori Deficient", care se traduce la "Spitalul de Acasă pentru Copii cu Deficiență".

În 1990, la scurt timp după căderea comunismului, producătorul Janice Tomlin, producatorul ABC News, a vizitat Sighet și a produs seria de premii "Rușinele unei națiuni". Fotografiile și videoclipurile lui Tomlin au adus atenția lumii asupra practicilor îngrozitoare ale copilului din România.

Ziarul comunist încurajează mamele să-și lase copiii în îngrijirea statului

Dan și Marlys Ruckel din San Diego au urmărit emisiunea de 20/20 și au mers în România cu intenția de a adopta un copil. La 29 octombrie 1991, Dan și Marlys au adoptat Izidor. El a fost unul dintre orfani de la Sighet pentru a face din San Diego noua lor casă.

În 2016, Izidor sa mutat înapoi în România, unde și-a dedicat viața copiilor fără familii și a găsit mijloacele necesare pentru a susține cele 60.000 orfani din generația sa, care nu au fost niciodată adoptați.

Recent, l-am intalnit pe Izidor la gara din Cluj pentru a vorbi despre viata lui, de ce sa mutat inapoi in Romania si despre starea actuala a protectiei copilului.

Spune-mi un pic despre starea ta

Între 3 și 11 ani, eram într-un spital pentru copii, nu un orfelinat. Dar, în acel moment, și încă astăzi, nu există nicio diferență între modul în care un copil este tratat într-un spital pentru copii sau într-un orfelinat de stat. Sunt ambele instituții.

Doi ani de la sosirea în SUA am început să pierd instituția de la Sighet. Nimeni din SUA nu a primit răspunsurile pe care le căutam și mi-am scos mânia pe cei care mă iubesc cel mai mult, pe familia mea adoptată. Eram copil din iad.

Apoi o familie română a venit la San Diego pentru Paște și am auzit despre Hristos. Am scris câteva întrebări și am început să găsesc răspunsurile pe care le căutam. Oamenii mă întreabă cum am depășit acest lucru. Nu este din cauza părinților mei sau a oricărui lucru pe care l-am făcut, pentru că l-am permis lui Hristos să-mi spună cine sunt cu adevărat.

Pe măsură ce furia mea sa diminuat și viața de familie sa îmbunătățit, mi sa cerut să scriu o carte pentru a ajuta familiile care adoptă copii abandonați. Cartea "Abandonată pentru viață" a fost publicată în 2003 și a vândut peste 30.000 de exemplare.

Timp de 17 ani, din 2001, obiectivul meu principal de viață a fost acela de a le spune oamenilor ce sa întâmplat în instituția mea și de a vă asigura că nu se mai întâmplă altor copii din România. Am vorbit de sute de ori, inclusiv pe BBC, la Washington Post și recent într-un interviu acordat lui Morgan Freeman, care va fi difuzat în octombrie în 176 de țări pe National Geographic.

DESCRIERE VIAȚĂ ÎN ORFANĂ

Ne-am trezit la 5 ani, dezbrăcați, deoarece majoritatea copiilor s-au umed în pat și s-au dus în altă încăpere pentru haine noi, în timp ce podeaua a fost curățată. Am mâncat micul dejun, am spălat-o și am fost puse într-o încăpere curată, unde stăteam acolo, înclinându-ne înainte și înapoi, lovind unii pe alții, dormind sau urmărind pe cineva să plângă până când erau drogați. După prânz, ne-am întors în camera curată, repetând aceleași lucruri ca dimineața. Apoi am fost hrăniți, scăldați din nou, purtați haine curate și în pat pentru noapte.

Ce dorești lumea să știe despre experiența ta?

În primul rând, copiii au suferit mai mult decât știe cineva. Niciun reporter nu poate surprinde suferința. Abuzul a fost mai rău decât orice a fost raportat. Dacă ai fost handicapat ca mine, ai fost ascuns și nu ai permis niciodată în afara instituției.

În al doilea rând, în ciuda tuturor traumelor și rănilor emoționale, nici o viață nu se pierde vreodată. Dacă dăm acestor copii, adulți acum, niște ocazii, cu dragoste, hrană și dezvoltare, ei pot funcționa în lume și pot dezvolta independența. Stau în legătură cu copiii cu care am crescut și pot fi ajutați. Au încă vise.

DE CE PĂSTRAȚI RETURAREA ÎN VIZIUNE?

Sunt multe motive. În primul rând, a fost casa mea timp de 11 ani și cred sau nu, există amintiri pe care le prețuim. De cîteva ori mi-a fost îngăduit să plec din instituție, eram în primejdie cu frumusețea naturală a Sighetului. România pentru mine a fost terenul frumos din afara instituției, nu răul din interiorul instituției.

Îmi place să vizitez unele dintre asistente. Le numesc cei șapte îngeri. Dragostea și compasiunea lor era singura sursă de speranță pe care o aveam.

Există, de asemenea, o amintire specifică care îmi amintește că Dumnezeu era cu mine, chiar dacă nu știam cine era El. Pe una din călătoriile mele în afara instituției, am văzut un om mort care atârna pe o cruce. Asistenta a spus că este Isus Hristos, dar fără nici o explicație. De fapt, am crezut că era un tip sărac de la Sighet.

Îmi pare rău pentru el când m-am întors la instituție. Acum fac o fotografie a acelei cruci de fiecare dată când mă întorc la Sighet.

Mă întorc să mă reconectez cu copiii cu care am crescut. În 2014, patru dintre noi s-au întors la instituție. Păpuși, mobilier și haine se aflau în jur ca și cum ar fi fost închise. Cioanele erau peste tot ca într-o casă bântuită. Dar era remarcabil faptul că fiecare dintre noi ne amintea lucrurile pe care ceilalți le uitaseră. Sa simțit foarte bine pentru noi să împărtășim experiența noastră obișnuită. Când i-am întrebat dacă au ratat acest loc, am spus toți "da". A fost singura noastră casă din copilărie.

Dar cel mai important motiv este să aflăm ce sa întâmplat cu adevărat acolo. Chiar dacă locul a fost închis timp de 11 ani, acesta este încă umplut cu înregistrări și materiale. Când aveam șapte ani, un puști pe nume Duma a fost bătut atât de rău încât m-am ascuns sub foi, temându-mă că aș fi următorul. Dimineața, am văzut cadavrul gol al Dumnei și, la prânz, a murit. Anul trecut mi-am găsit înregistrările medicale. Cauza sa oficială de moarte a fost "oprită de respirație".

Mai era un alt copil numit Marian, care era hiperactiv și căruia i se dădea adesea medicamente. Tatăl lui la vizitat în fiecare weekend și m-aș gândi cu gelozie pe fereastră, în timp ce ei stăteau pe o bancă. În timp, Marius a încetat să mănânce și a pierdut voința de a trăi. Îmi amintesc că am văzut fereastra duminică când a murit în brațele tatălui său. Tatăl său plângea și se ruga în ceruri.

În 1995, a existat o poveste despre mass-media că orfanii români au primit otrava șobolanilor. Acum trei ani, o asistentă medicală din instituție a confirmat că Marius și mulți alți copii au primit otrava șobolanului.

Multe foști orfani se întorc în România pentru a răspunde. Pentru mine, este vorba de iertare și de asigurarea că România nu se mai ocupă de problema bunăstării copilului sub covor. Drepturile și interesele copiilor sunt încă ignorate.

La 1 iunie 2017, investigația crimă comunistă (ICCMER) finanțată de stat a înaintat o plângere penală Ministerului Justiției pentru decesele a 771 de copii din orfelinatele din Sighetu Marmatei, Cighid și Pastraveni între 1966 și 1990. Investigatorii spun că este doar vârful aisbergului pentru o investigație mult mai amplă care este necesară în cele 26 de orfelinate din România.

ICCMER anchetatorii și arhiviștii declară că dosarele oficiale arată că pneumonia și boala cerebrală sunt principalele cauze ale deceselor, dar martorii spun că cauzele au fost expunerea la frig, igiena slabă, înfometarea, lipsa asistenței medicale, otravă șobolan și abuz fizic violent.

Anchetatorii spun că înregistrările comuniste au clasificat copiii în trei categorii: reversibile, parțial reversibile și nereversibile. Copiii din ultimele două categorii au fost aruncați în centre pentru a muri.

Radu Preda, directorul ICCMER, spune: "Plecarea mea ca tată este să mă asigur că aceste lucruri nu se mai întâmplă niciodată. Să facem ceva la nivel mediatic și la nivel instituțional pentru a ne asigura că niciun copil din această țară care are handicap, boală sau a fost abandonat va fi vreodată lovit de foame, înfometat, legat sau lăsat să moară în fecale proprii.

Trebuie să recunoaștem societatea absolut necivilizată a trecutului comunist și să eliminăm toate urmele acestei boli de la sistemul nostru de protecție a copilului ".

Spune-mi despre investigația penală din care fac parte?

Am convenit să ajut să atragem atenția asupra unei anchete penale conduse de Institutul pentru Investigarea Crimelor Comunismului (ICCMER). Această anchetă se axează pe decesele copiilor din Sighet Marmației și alte două instituții.

I-am cerut anchetatorilor să meargă după asistente și au spus: "Nu, doar cei care au eliberat medicamentul și au reușit să-i ajute." Odată ce am știut asta, era bine cu mine.

Dar sunt mai puțin interesat să pun oamenii în închisoare decât mă interesează să obțin resurse financiare de la stat pentru a susține cele 60.000 orfani din generația mea care nu au fost niciodată adoptați. Mulți dintre ei nu au nici un mijloc de a se susține ca adulți și sunt fără adăpost. Speranța mea este că această anchetă va conduce la un proces mult mai mare de acțiune în numele acestor 60.000 de cetățeni. Trebuie să existe un cost pentru o neglijență gravă sau lucrurile nu se vor schimba.

Spune-mi cum se referă MEDIA ROMÂNĂ LA ABUZIREA COPILULUI ȘI BINE DEPĂȘĂMÂNTĂ

Nu puteam să cred toată mass-media românească la conferința de presă din 1 iunie anunțând ancheta penală. A fost istorie! Românii se luptă în cele din urmă pentru ceva ce nu am reușit să facem toți acești ani. Mereu provoacă mass-media din România, deoarece toate poveștile despre orfani și abuzul asupra copilului provin din organizațiile internaționale de știri. Chiar și astăzi, toate materialele de neglijare a copilului provin de la organizații internaționale.

De ani de zile, oamenii erau stânjeniți și speriat de această problemă. Dar acum se pare că tinerii se trezesc la faptul că acest lucru se întâmplă în continuare.

ESTE MAI ABUZĂ ÎN INSTITUȚII DIN ROMÂNIA

Da este. Nu știu din experiență, dar am auzit de la oamenii pe care îi cunosc și de încredere. Încerc să obțin acces la mai multe instituții pentru a ajuta copiii și lucrătorii sociali. Nu locuiesc în România ca să-i stârnesc sau să distrug oamenii. Dar oficialii guvernamentali din Parlament nu par să știe ce se întâmplă cu adevărat în instituțiile lor.

GĂSIȚI că România ar trebui să deschidă adoptarea internațională?

Mă lupt pentru adopția internațională pentru copiii cu nevoi speciale sau cei care nu au șanse să fie adoptați în România. Majoritatea oamenilor din guvern resping această idee pe baza faptului că copiii vor fi distruși prin pierderea culturii și a identității lor dacă vor fi adoptați în afara României.

E o scuză groaznică. Din momentul în care acești copii intră în instituție, ei sunt dezbrăcați de tot. Demnitatea, libertatea și creierul lor devin ciuperci. Spuneți-mi ce culturi pierdeți prin adoptarea în străinătate?

Problema din România în prezent se referă la bani și locuri de muncă pentru patronajul politic. Statul plătește pentru fiecare copil instituțiile, casele rezidențiale și asistența maternală. Dacă statul a găsit familii adoptive pentru 20.000 dintre cei 60.000 de copii aflați în custodia statului, aceștia ar pierde 33% din finanțarea lor și locurile de muncă pe care le oferă adesea familiei și prietenilor.

În generația mea, guvernul a vrut să dispună de copii. Astăzi, vor să profite de la ei

CE CEL MAI MULTE DESPRE SISTEMUL DE COPII?

Sunt de fapt impresionat de câți lucrători sociali buni vor să schimbe sistemul. Am primit o mulțime de e-mailuri de la asistenții sociali și am fost șocat să văd câte lucrători sociali au apărut la conferința România fără orfan în noiembrie anul trecut. Este o mare bucurie să vedem toate familiile românești care au adoptat și vor să adopte.

Știm cu toții că instituțiile nu sunt răspunsul. Dar nu sunt în favoarea închiderii instituțiilor. Simpla punere a copiilor pe străzi este și mai rău. Cel puțin instituțiile oferă un pat, alimente, îmbrăcăminte și adăpost. Gările noastre sunt pline de persoane fără adăpost.

Cea mai mare problemă pe care o avem astăzi este că lucrătorii care au lucrat în instituții în anii '80 până la mijlocul anilor '90 încă lucrează în sistem. Nu vă puteți aștepta la schimbări prin renovarea clădirilor atunci când aveți aceiași oameni și aceeași cultură.

Am vizitat 6 orfelinate acum 2 ani. Cei mai mulți dintre copii au văzut povestea mea la televizor și mi-au făcut plăcere să vorbesc cu mine. I-am cerut fiecărui copil: "Vă place să locuiți aici?" Ei au spus: "Vedeți doamna de acolo? Încă ne bate. "Am întrebat" cât timp a lucrat aici? "Ei au spus" din prima zi, de când acest loc a fost deschis ".

Este în mod constant același răspuns. Și m-am gândit "Wow, este problema." Acești oameni trebuie să fie înlocuiți.

Vreau să lucrez cu sistemul. Vreau să rămân în România. Pot să văd că oamenii caută răspunsuri. Am un răspuns puternic când vorbesc cu noua generație de români. Cred că este momentul potrivit să ne confruntăm cu trecutul nostru și să creăm un sistem care să funcționeze în interesul copiilor.

CONCLUZIA AUTORULUI

Am fost mutat de Izidor. Călătorește în jurul României pe trenuri murdare. El își poartă valiza fără plângere, în ciuda unui picior paralizat parțial. Nu are mulți bani și nu este motivat de faima sau atenția publicului. Ceea ce are este o pasiune și un scop.

România în 2017 îmi amintește că am crescut în Germania în anii '70. Îmi amintesc să vorbesc cu prietenii mei germani despre adolescență și despre nazism și despre Holocaust. Ei nu aveau nici un răspuns, nici o abilitate de a înțelege groaza, doar o pasiune profundă de a lupta împotriva oricărei moșteniri a nazismului. Simt același sentiment în rândul tinerilor români de astăzi, deoarece se simt înfuriați profund față de orice abuz sau nedreptate față de copii.

Este cliché să spunem că viitorul nostru este în copiii noștri. Dar în România numerele vorbesc de la sine.

Fiecare decizie luată în casele, comunitățile și guvernul nostru trebuie făcută în contextul "Este un loc bun pentru creșterea copiilor sănătoși și facem tot ce putem pentru a găsi fiecare copil o familie iubitoare?"

December 11, 2017

România sa renăscut – atunci și acum. Povestea de credință a lui Corina

Ea a crescut în zilele cele mai întunecate ale comunismului, fiica unui predicator penticostal. Își amintește că a fost batjocorită pentru credința ei în fiecare zi la școală. Își amintește că aruncă o privire sub ușa dormitorului pe timp de noapte, uitându-se la cizmele soldaților care veniseră să-i ia tatăl pentru interogatoriu. Își amintește cum a fost atunci când comunismul a căzut în cele din urmă și a aflat că guvernul a ascuns sute de mii de copii în orfelinate teribile. Și atunci Corina Caba știa ce vrea Dumnezeu să facă cu viața ei.

Ea și-a fondat orfelinatul într-un apartament mic în 1996, luând copiii abandonați din spital și îngrijindu-i până când a putut găsi familii adoptive. Treptat, ea a adăugat la personalul ei, plătindu-și salariile oricât ar fi putut. După ce România a fost înființată pentru a susține lucrarea, ea a construit o unitate mai mare, a angajat mai mulți muncitori și a luat mai mulți copii. Odată cu trecerea anilor, legile și sistemul de protecție a copilului au evoluat, însă Dumnezeu a făcut întotdeauna o cale pentru Corina să-i ajute pe copii abandonați.

Corina cu un copil abandonat la spital în 2005

https://www.romania-reborn.org/…/11/8/corinas-story-of-faith[image error]

Astăzi, Corina este mama adoptivă a patru copii și o figură mamă la sute de persoane, a căror viață sa schimbat pentru totdeauna. Ea este, de asemenea, un lider național în curs de dezvoltare în domeniul îngrijirii orfane, călătorește pentru a vorbi la conferințe, ajutându-i să consilieze guvernul cu privire la politică și (cu reticență) vorbind cu mass-media națională. Și încă luptă pentru copiii individuali în fiecare zi. "Când durerea este prea mare, Dumnezeu ma învățat să am încredere în El", spune ea. "Într-o zi, El va restaura tot ce pare pierdut, va răscumpăra tot ce pare fără speranță, va repara tot ce pare distrus. Dumnezeul nostru are ultimul răspuns!"

Dăruiți darul de angajament

Cadoul dvs. va ajuta personalul nostru angajat să lupte cu pasiune pentru copiii aflați în îngrijirea noastră, susținând practici guvernamentale mai bune și utilizând sediul central al ministerelor noastre ca centru de instruire și consiliere pentru familii. Puteți să vă adresați următoarelor nevoi ale personalului și ale ministerului:

$ 50: ONE SĂPTĂMÂNĂ DE CHELTUIELI DE GAZ / CĂLĂTORIE (PENTRU LUCRĂRI SOCIALE)

250 USD: ONE LUNA CHELTUIELILOR ELECTRICE (PENTRU SANATOARE)

600 de dolari: SALAREA UNEI LUNI PENTRU UN LUCRU SOCIAL

GASITI ACUM

Romania Reborn; Hands of Hope

She grew up during the darkest days of Communism, the daughter of a Pentecostal preacher. She remembers being mocked for her faith every day at school. She remembers peeking under her bedroom door at night, watching the boots of the soldiers who had come to take her father away for interrogation. She remembers what it was like when Communism finally fell, and she learned that the government had hidden hundreds of thousands of children away in terrible orphanages. And that was when Corina Caba knew what God wanted her to do with her life.

She founded her orphanage in a tiny apartment in 1996, taking abandoned babies from the hospital and caring for them until she could find adoptive families. Gradually, she added to her staff, paying their salaries however she could. After Romania Reborn was founded to support the work, she built a bigger facility, hired more workers, and took in more babies. As the years passed, Romania’s laws and child welfare system evolved, but God always made a way for Corina to help abandoned children.

Today, Corina is the adoptive mother of four children and a mother figure to hundreds more, whose lives she has forever changed. She is also an emerging national leader in the field of orphan care, traveling to speak at conferences, helping advise the government on policy, and (reluctantly) speaking to national media. And she’s still fighting for individual children every day. “When the pain is too much, God taught me to trust in Him,” she says. “One day, He will restore all that seems lost, redeem all that seems hopeless, repair all that seems destroyed. Our God owns the last reply!”

Give the Gift of Commitment

Your gift will help our committed staff keep passionately fighting for the children in our care, advocating for better government practices, and using our ministry headquarters as a training and counseling center for families. You can give toward the following staff and ministry needs:

$50: ONE WEEK OF GAS/TRAVEL EXPENSES (FOR SOCIAL WORK)

$250: ONE MONTH OF ELECTRIC EXPENSES (FOR HEADQUARTERS)

$600: ONE MONTH SALARY FOR A SOCIAL WORKER

GIVE NOW

Corina holding an abandoned baby at the hospital in 2005. https://www.romania-reborn.org/…/11/8...

December 10, 2017

Government Officials in Romania Leave a Family of Five to Starve

Government officials in Romania leave a family of five to starve.

Four children, left by their mother, in Handalu Ilbei, a Village in Maramures, live in poverty in a house ready to fall down.

They have days when they eat nothing but forest fruits, if the neighbours do not pity them and prepare something for them to eat.

Their mother left them about one year ago. The children go to a normal school but have not been properly assessed.

The four children live off an allowance and the money that their father sometimes earns from working in the Village.

Officials at the Cicarlau Town Hall, to which the Village belongs, say that they cannot help because the father doesn’t work for the community.

The four children are aged between six and fifteen years old. The eldest girl is in charge of washing and cooking.

They complain to their father that they have nothing to eat and go to school barefoot in the winter.

The father does not drink and is doing his best to send the children to school.

Abandonaţi de mamă, patru copii trăiesc într-o cocioabă la marginea civilizaţiei. „Toţi merg la şcoală. Desculţi, că n-au cu ce se încălţa“

oficialii guvernamentali din România lasă o familie de cinci persoane să moară de foame.

Patru copii părăsiţi de mamă din localitatea maramureşeană Handalu Ilbei trăiesc la limita sărăciei, lângă tatăl lor, într-o căsuţă mică, sărăcăcioasă, gata să se dărâme. Au zile în care mănâncă doar fructe de pădure, dacă nu-şi fac milă vecinii să le pregătească ceva de mâncare.

Un tată cu patru copii din Handalu Ilbei trăiesc la limită, într-o căsuţă sărăcăcioasă. Mama lor i-a părăsit în urmă cu aproape un an, iar de atunci, de ea nu mai ştiu nimic.

Copiii au probleme de adaptare, însă în lipsa unor evaluări ale specialiştilor merg la o şcoală normală, unde fac faţă cu greu cerinţelor. Din păcate, sărăcia şi lipsurile vin, de obicei, „la pachet” cu alte necazuri. Cei patru minori trăiesc doar din alocaţie şi din puţinii bani pe care îi prmeşte tatăl lor, muncind prin sat, cu ziua. Însă nu mereu.

Câteva femei din vecini îşi fac milă şi le mai oferă micuţilor o farfurie cu mîncare, ori o vorbă bună. Rodica Mureşan, o femeie a cărei mamă locueşte în vecini de cei patru copii, spune că a încercat să se implice să-i ajute, însă fără succes, până acum.

„Am fost personal la Primăria Cicârlău (de care aparţine satul) şi am sesizat Asistenţa Socială despre cazul lor. Au spus că nu le pot da ajutor social, pentru că bărbatul nu munceşte în folosul comunităţii. Şi eu sunt absolvent de Asistenţă Socială şi cunosc legea. Dar trebuie văzut fiecare caz în parte, unii oameni chiar nu sunt capabili de muncă. El a muncit o perioadă în folosul comunităţii, dar pe urmă n-a mai mers”, explică Rodica Mureşan.

Ea mai arată că cei patru copii au vârste cuprinse între 6 şi 15 ani. „De când a plecat mama lor, fata cea mare se ocupă de spălat şi gătit. Numai că nu au, bieţii de ei, uneori, nimic ce pune pe masă. Se plâng tatălui lor că le e foame şi nu au nimic ce să mănânce. Au zile în care tot ce mănâncă sunt fructe de pădure”, mai spune ea revoltată.

Mai mult, femeia spune că bărbatul nu are obiceiul să consume alcool şi că face tot posibilul să-i trimită pe cei mici la şcoală. „Toţi merg la şcoală. Sunt desculţi, nu au ce să încalţe. Am fost pe la tot felul de organizaţii şi am încercat să le găsesc încălţăminte, dar deocamdată nu au”, mai spune ea.

http://fixininimata.biz/2017/12/aband...

December 8, 2017

Romania Without Orphans Alliance Report on Adoption

The degree of declaration of adoptability did not increase at all one year after the revised law on adoption was implemented, keeping it below 6% of the number of children in the system.

In March 2016, there were 57,581 children who had been abandoned by their families and entered the child protection system.

This report is the result of an analysis of the situation of abandoned children in the child protection system, carried out by the Romania Without Orphans Alliance.

The report was made public at the start of the A.R.F.O Summit, held in Bucharest, November 2017.

The report shows that the declaration of adoption for children where there is no possibility of being reunited with their biological families, is hampered by over exaggerated legislation and poor implementation of legislation.

The very small number, only 1.5% of children being adopted, highlights a worrying practise to keep children in institutions.

Another aspect highlighted by the report is that, whilst private organisations are not allowed to provide services unless they are licensed, 83% of public services do not have a license and do not meet mandatory minimum standards.

Raportul ARFO cu privire la situația copiilor din sistemul de protecție