Adele Rickerby's Blog, page 7

December 8, 2017

raportează despre abandonat copii

BY ECHIPA ROMANIAPOZITIVA ON 24 NOIEMBRIE 2017OAMENI ȘI COMUNITĂȚI, ROMÂNIA

Gradul de declarare a adoptabilității nu a crescut deloc după un an de la modificarea legii privind regimul juridic al adopției, acesta menținându-se sub 6% din numărul copiilor din sistem.

Raportul este disponibil aici:

https://tzubyskids.ro/2017/11/23/raportul-arfo-cu-privire-la-situatia-copiilor-din-sistemul-de-protectie/

Prezentul raport este rezultatul unei analize a situației copiilor din sistemul de protecție realizată de Alianța România Fără Orfani și a fost lansat în deschiderea Summit-ului ARFO 2017 organizat în București, la Crystal Palace Ballrooms.

Raportul arată că declararea adoptabilităţii pentru copiii fără posibilitate de reintegrare în familia biologică este îngreunată atât de prevederi legislative exagerate, cât şi de o aplicare deficitară a legislaţiei. Ca şi cum nu ar fi suficient, ponderea extrem de mică de copii adoptabili din rândul copiilor instituţionalizaţi (1,5%) sugerează o practică îngrijorătoare de a menţine copiii în sistem cu statut de neadoptabil.

Un alt aspect subliniat de raport este faptul că, în timp ce organismele private nu au voie să furnizeze servicii nelicenţiate, 83% dintre serviciile publice nu au licenţă şi nu îndeplinesc standardele minime obligatorii. Astfel, nivelul de calitate al asistenţei sociale în domeniul protecţiei copilului necesită mai multă atenţie impunându-se măsuri de încurajare a parteneriatelor între DGSAPC şi organismele private acreditate, acestea fiind de natură să ducă la îmbunătăţirea calităţii serviciilor în domeniu.

Pe de altă parte, raportul subliniază evoluţii pozitive prin deschiderea listei de „greu adoptabili”, prelungirea până la 14 ani a declarării adoptabilităţii, concomitent cu extinderea valabilităţii atestatului de părinte adoptator la 2 ani.

Raportul ARFO 2017 propune și soluții pentru îmbunătățirea situației identificate printre care reducerea gradului IV până la care se caută rudele în vederea declarării adoptabilității copiilor din sistem, interzicerea tranzitării copiilor din medii familiale în medii instituționalizate și emiterea standardelor minime pentru plasament familial.

[image error] [image error]

November 11, 2017

Shame of A Nation

Shame of a Nation

Don Lothrop

26.10.2017

Izidor Ruckel was born in 1980. When he was six months old, he became ill and his parents took him to a hospital where he contracted polio from an infected syringe. Later, the hospital doctors encouraged his parents to drop him off at an orphanage. From 1983 until 1991, Izidor lived in the Sighetu Marmatiei orphanage.

No one knows how many children were in Romanian orphanages at end of communism. The number is estimated to have been somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000. What we do know is that child abandonment was actually encouraged by the Romanian government as a means of population growth by discarding children who could not be productive workers for the state.

Sighetu Marmatiei is located in Sighet, a small city in northern Romania. It is the hometown of Holocaust survivor and Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel.

The Sighetu Marmatiei institution is located on the western edge of town behind a 6-foot wall. The sign above the entry reads “Camin Spital Pentru Minori Deficient,” which translates to the “Hospital Home for Deficient Children.”

In 1990, shortly after communism fell, ABC News’ 20/20 producer Janice Tomlin visited Sighet and produced the awarding series “Shame of a Nation.” Tomlin’s photos and videos brought the world’s attention to Romania’s horrific child welfare practices.

Communist newspaper encourages Mothers to leave their children in State Care

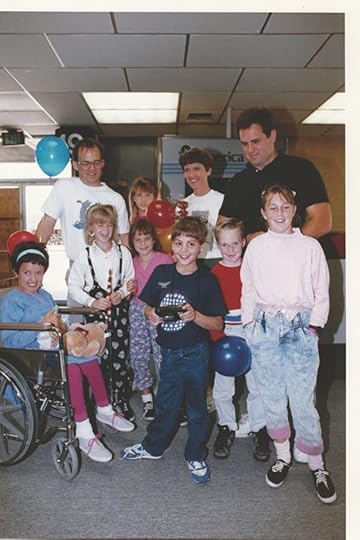

Communist newspaper encourages Mothers to leave their children in State CareDan and Marlys Ruckel of San Diego watched the 20/20 broadcast and went to Romania with the intention of adopting a child. On October 29, 1991, Dan and Marlys adopted Izidor. He was one of many Sighet orphans to make San Diego their new home.

In 2016, Izidor moved back to Romania, where he has committed his life to children without families and finding the means to support the 60,000 orphans of his generation who were never adopted.

Izidor meets his new mother

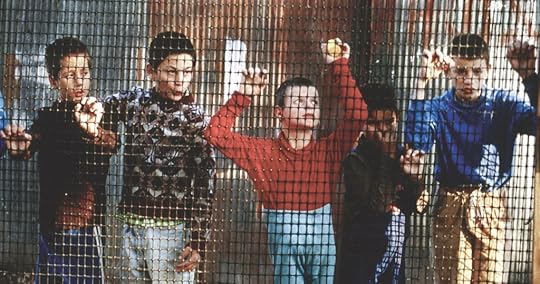

Izidor meets his new mother 1990 – Izidor behind orphanage bars

1990 – Izidor behind orphanage bars Izidor’s family

Izidor’s familyI recently met Izidor at the Cluj train station to talk about his life, why he moved back to Romania, and the current state of child welfare.

TELL ME A LITTLE ABOUT YOUR BACKGROUND

From 3 until 11, I was in a hospital for children, not an orphanage. But back then, and still today, there is no difference between how a kid is treated in a children’s hospital or a state orphanage. They are both institutions.

Two years after arriving in the US, I started to miss the institution in Sighet. Nobody in the US had the answers that I was looking for, and I took out my anger on the people that loved me most, my adopted family. I was a child from hell.

Then a Romanian family came to San Diego for Easter and I heard about Christ. I wrote down tons of questions and began to find the answers I was searching for. People ask me how I overcame this. It isn’t because of my parents or anything I did, it was because I allowed Christ to tell me who I really was.

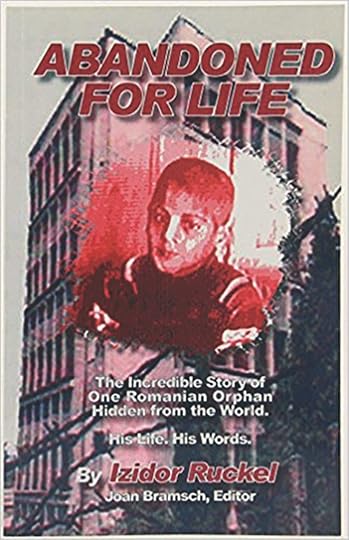

As my anger subsided and family life improved, I was asked to write a book to help families who adopt abandoned children. The book, Abandoned for Life, was published in 2003 and sold over 30,000 copies.

Izidor in the US with his father

Izidor in the US with his fatherFor 17 years, since 2001, my primary life goal has been to tell people what happened in my institution and make sure it stops happening to other children in Romania. I have spoken hundreds of times, including on the BBC, in the Washington Post and recently in an interview with Morgan Freeman that will be aired this October in 176 countries on National Geographic.

DESCRIBE LIFE IN THE ORPHANAGE

We woke up at 5, stripped naked, since most kids wet themselves in bed, and went to another room for new clothes while the floor was cleaned. We ate breakfast, washed up and were put into a clean room where we just sat there rocking back and forth, hitting each other, sleeping or watching someone cry until they were drugged. After lunchtime, we went back into the clean room, repeating the same things as the morning. Then we were fed, bathed again, put into clean clothes and into bed for the night.

WHAT DO YOU WANT THE WORLD TO KNOW ABOUT YOUR EXPERIENCE?

First, that the children suffered more than anyone knows. No reporter can capture the suffering. The abuse was worse than anything reported. If you were handicapped like me, you were hidden and never allowed outside the institution.

Secondly, despite all trauma and emotional wounds, no life is ever lost. If we give these kids, now adults, some opportunity, with love, nourishment and development, they can function in the world and develop independence. I stay in touch with the kids I grew up with and they can be helped. They still have dreams.

WHY DO YOU KEEP RETURNING TO SIGHET ?

There are many reasons. First off, it was my home for 11 years and believe it or not, there are memories I cherish. The few times I was allowed out of the institution, I was in awe of the natural beauty of Sighet. Romania to me was the beautiful land outside the institution, not the evil inside the institution.

I like to visit some of the nurses. I call them my seven angels. Their love and compassion was the only source of hope I had.

There is also a specific memory that reminds me that God was with me even though I did not know who He was. On one of my trips outside the institution, I saw a dead man hanging on a cross. The nurse said it was Jesus Christ, but without any explanation. I actually thought he was some poor guy from Sighet.

I kept feeling sorry for him when I got back to the institution. Now I take a picture of that cross every time I am back in Sighet.

I go back to reconnect with the kids I grew up with. In 2014, four of us went back to the institution. Dolls, furniture and clothes were lying around like it just closed. Crows were everywhere like in a haunted house. But it was remarkable that each of us remembered things that the others had forgotten. It felt really good for us to share our common experience. When I asked them if they missed this place, we all said ‘yes’. It was our only childhood home.

But the biggest reason is to find out what really happened there. Even though the place had been closed for 11 years, it is still filled with records and supplies. When I was seven, a kid named Duma was beaten so badly that I hid under the sheets, fearful that I might be next. In the morning, I saw Duma’s naked bruised body and by lunch he was dead. Last year I found his medical records. His official cause of death was “stopped breathing.”

There was another kid named Marian who was hyperactive and was often given medicine. His father visited him every weekend and I would jealously look out the window as they sat on a bench. In time, Marius stopped eating and lost the will to live. I remember looking out the window on the Sunday when he died in his Dad’s arms. His Dad was crying and praying to heaven.

In 1995, there was a media story that Romanian orphans were given rat poison. Three years ago, a nurse from institution confirmed that Marius and many other kids were given rat poison.

Many former orphans are returning to Romania for answers. For me, it is all about forgiveness and making sure Romania stops sweeping the child welfare issue under the carpet. Children’s rights and interests are still being ignored.

From left to right: historian Mia Jinga, Izidor Ruckel and the director of IICCMER, Radu Preda. Photo: Lucian Muntean

From left to right: historian Mia Jinga, Izidor Ruckel and the director of IICCMER, Radu Preda. Photo: Lucian MunteanOn June 1, 2017, the state-funded Investigation of Communist Crimes (ICCMER) submitted a criminal complaint to the Ministry of Justice for the deaths of 771 children in the Sighetu Marmatei, Cighid and Pastraveni orphanages between 1966 and 1990. Investigators say this is just the tip of the iceberg for a much wider investigation that is needed into Romania’s 26 orphanages.

ICCMER investigators and archivists say official records list pneumonia and brain disease as the main causes of deaths, but witnesses say the causes were exposure to the cold, poor hygiene, starvation, lack of healthcare, rat poison, and violent physical abuse.

Investigators say Communist records classified children into 3 categories: reversible, partially reversible and non- reversible. Children in the latter two categories were thrown into centers to die.

Radu Preda, director of ICCMER says “My plea as a father is to ensure that these things never happen again. Let us do something on the media level and at the institutional level in order to ensure that no child in this country who has a handicap, or illness, or has been abandoned will ever be slapped, starved, tied down or left to die in their own feces.

We need to acknowledge the utterly uncivilized society of our communist past and rid all traces of this sickness from our child protection system.”

TELL ME ABOUT THE CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION YOU ARE A PART OF?

I agreed to help bring attention to a criminal investigation led by the Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes (ICCMER). This investigation focuses on the deaths of children in Sighet Marmatiei and two other institutions.

I asked the investigators if they were going after nurses and they said “No, only the people who dispensed medicine and managed the facilities.” Once I knew that, it was okay with me.

But I am less interested in putting people in jail than I am interested in getting financial resources from the State to support the 60,000 orphans of my generation that were never adopted. Most of them have no means to support themselves as adults and are homeless. My hope is that this investigation will lead to a much larger class action suit on behalf of these 60,000 citizens. There needs to be a cost for gross neglect or things will not change.

TELL ME ABOUT HOW THE ROMANIAN MEDIA COVERS CHILD ABUSE AND WELFARE

I could not believe all the Romanian media at the June 1st press conference announcing the criminal investigation. This was history! Romanians finally fighting for something that we failed to do all these years. I always challenge the Romanian media since all of the stories on orphans and child abuse come from international news organizations. Even today, all the footage of child neglect comes from international organizations.

For years people were embarrassed and scared about this issue. But now it seems young people are waking up to the fact that this is still going on.

IS THERE STILL ABUSE IN ROMANIA INSTITUTIONS

Yes there is. I do not know from firsthand experience, but I have heard so from people I know and trust. I am trying to get access to more institutions to help kids and social workers. I am not living in Romania to embarrass or destroy people. But the government officials in Parliament seem to have no clue what is really happening in their institutions.

DO YOU THINK ROMANIA SHOULD OPEN INTERNATIONAL ADOPTION?

I am fighting for international adoption for children with special needs or those that have no chance of being adopted in Romania. Most of the people in the government reject this idea on the basis that children will be damaged by losing their culture and identity if they get adopted outside of Romania.

That’s a horrible excuse. From the moment these children enter the institution they are stripped of everything. Their dignity, freedom and their brains become mush. Tell me, what culture are they losing by being adopted abroad?

The issue in Romania today is all about money and jobs for political patronage. The State pays institutions, residential homes and foster care a stipend for each child. If the State found adoptive families for 20,000 of the 60,000 children in State custody, they would lose 33% of their funding and the jobs they often give to family and friends.

In my generation, the government wanted to dispose of the children. Today, they want to profit from them.

WHAT BOTHERS YOU THE MOST ABOUT THE CHILDCARE SYSTEM TODAY?

I am actually impressed with how many good social workers want to change the system. I get lots of emails from social workers and was shocked to see how many social workers showed up at the Romania Without Orphans conference last November. It is a great joy to see all of the Romanian families that have adopted and want to adopt.

We all know that institutions are not the answer. But I am not in favor of just shutting down the institutions. Simply putting kids on the streets is even worse. At least institutions provide a bed, food, clothing and shelter. Our train stations are filled with homeless.

The biggest problem we have today is that the workers who worked in the institutions in the 1980’s through the mid-1990’s still work in the system. You can’t expect change by renovating buildings when you have the same people and same culture.

I visited 6 orphanages 2 years ago. Most of the kids saw my story on television and were comfortable talking to me. I asked each child, “Do you like living here?” They said “See that lady over there? She still beats us.” I asked “how long she has been working here?” They said “from day one, since this place opened.”

It is constantly the same response. And I thought “Wow, there is the problem.” These people need to be replaced.

I want to work with the system. I want to stay in Romania. I can see that people are really looking for answers. I am getting a powerful response when I speak to the new generation of Romanians. I believe the time is right to confront our past and create a system that works in the interests of children.

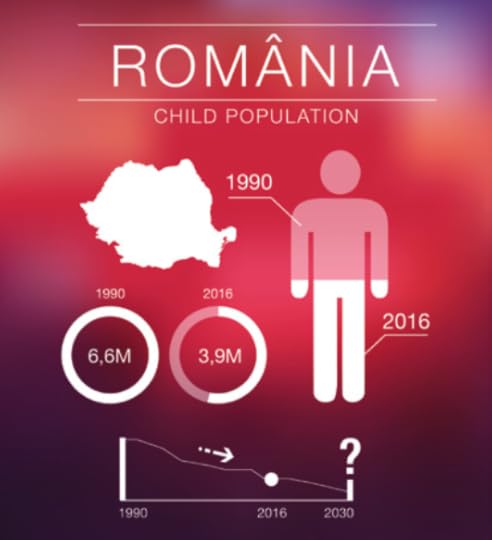

The massive decline in child population is the greatest threat to Romania’s future

The massive decline in child population is the greatest threat to Romania’s futureAUTHOR’S CONCLUSION

I was moved by Izidor. He travels around Romania on filthy trains. He carries his suitcase without complaint, despite a partially paralyzed leg. He does not have much money and is not motivated by fame or public attention. What he has is a passion and purpose.

Romania in 2017 reminds me of growing up in Germany in the 1970’s. I remember talking to my German teenage friends about Nazism and the Holocaust. They had no answers, no ability to comprehend the horror, just a deep passion to fight any legacy of Nazism. I feel the same sentiment among young Romanians today as they feel deep anger towards any abuse or injustice towards children.

It is cliché to say that our future is in our children. But in Romania the numbers speak for themselves.

Every decision made in our homes, communities and government, needs to be made in the context of “Is this a good place to raise healthy children and are we doing our best to find every child a loving family?”

Izidor is in desperate need of a new leg-brace for his polio damaged leg. Please see the link and share or donate if you can.

Thank you for your support

https://www.youcaring.com/izidorruckel-905158

October 28, 2017

Morgan Freeman; The Story of Us; The Power of Love.

Valentin Naș is  watching The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman

watching The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman

“The Power of Love” is the title of the third episode of the National Geographic series “The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman”. The episode includes Izidor Ruckel’s life story. Izidor spent the first 11 years of his life without the love and support of a family. For 8 years, he survived horrific conditions in one of the most terrifying “child care” institutions during the Ceauşescu era, the Home-hospital for the irrecoverables in Sighet. In 1991, he was adopted by Danny and Marlys Ruckel and started a new life in America. However, all the attachment issues he developed due to the lack of love in the early childhood needed a long time to heal. And not just time.

Morgan Freeman interviewed Danny and Marlys on their efforts to reach such a broken boy with the power of love…

All you need is love!

The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman S01E03 – The Power of Love

Polio is a crippling disease. Izidor desperately needs a new leg brace for his polio damaged leg. Please donate if you can and thank you for your support.

Click here to support New leg brace for Izidor Ruckel

Please continue to share . Also please share Izidor’s press release. https://izidorruckel.com/2017/10/morgan-freeman-interviews-izidor-ruckel-for-new-mini-series/

YOUCARING

Morgan Freeman; The Power of Love

Valentin Naș is  watching The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman

watching The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman

“The Power of Love” is the title of the third episode of the National Geographic series “The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman”. The episode includes Izidor Ruckel’s life story. Izidor spent the first 11 years of his life without the love and support of a family. For 8 years, he survived horrific conditions in one of the most terrifying “child care” institutions during the Ceauşescu era, the Home-hospital for the irrecoverables in Sighet. In 1991, he was adopted by Danny and Marlys Ruckel and started a new life in America. However, all the attachment issues he developed due to the lack of love in the early childhood needed a long time to heal. And not just time.

Morgan Freeman interviewed Danny and Marlys on their efforts to reach such a broken boy with the power of love…

All you need is love!

The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman S01E03 – The Power of Love

Izidor desperately needs a new leg-brace for his polio affected leg. Please donate and share this link if you are able.

Click here to support New leg brace for Izidor Ruckel

Please continue to share . Also please share Izidor’s press release. https://izidorruckel.com/2017/10/morgan-freeman-interviews-izidor-ruckel-for-new-mini-series/

YOUCARING

October 2, 2017

Cursed Romania; Nearly Ten Thousand Children Abandoned in the Past year.

Cursed Romania! Nearly 10,000 children have been ABANDONED by their parents in the past year. The international bodies have identified the causes for a decision at the limit of cruelty

Nearly 10,000 children were abandoned by their parents in the last year, the number being lower compared to the previous year. The main cause of this phenomenon is poverty, according to statistics provided by the National Authority for the Protection of Child’s Rights and Adoption (ANPDCA).

According to the ANPDCA response at a MEDIAFAX request, data provided by the General Directorates for Social Assistance and Child Protection in the counties / sectors of Bucharest Municipality which have been centralized on a quarterly basis, show that between July 2016 and June 2017 a total of 9,614 children were separated from their families and entered into the special protection system (placement with relatives up to 4th grade, placement with other families / persons, placement in foster care and placement in residential services).

The same source shows that between July 2015 and June 2016, a total of 10,196 children entered the special protection system.

According to the study “Romania: Children within the Child Protection System” conducted by the World Bank, UNICEF and the ANPDCA, the three main causes – constantly identified – for the child being separated from the family and entering the child protection system, are poverty, abuse and neglect, and disability.”

According to data available at ANPDCA, most of the children in the special protection system come from poor or at-risk families living in precarious housing conditions.

Of the total number of children in the special protection system, about 36% had poverty as a structural risk factor as the main cause of child’s separation from the family of the child child.

The mentioned source states that about 32% of the children in the special protection system were abandoned by parents, and 10% of the children in the special protection system were taken over by the care system from their relatives.

According to the same source, “the counties with the highest number of children entering the special protection system were Iaşi, Vaslui, Timiş, Constanţa, Buzău”.

On the opposite side, says ANPDCA, are the counties of Ilfov, Gorj, and Sectors 3, 5 and 6 of Bucharest.

mediafax.ro Sept.2017

September 19, 2017

The Tragedy of Babies Abandoned in Romanian Hospitals

Tragedy of children left in Romanian hospitals continues: 245 newborn babies were abandoned in the first three months of 2017

According to data published on the website of the National Authority for the Protection of Children’s Rights and Adoption (ANPDCA), 245 children were left in maternity wards and other health care facilities during the first quarter of 2017. According to the same data, last year about 1,000 children were abandoned in hospitals.

Out of the 245 children left in medical units, 164 were abandoned in maternity wards, 71 in pediatric wards, and 10 were left in other hospital departments.

Also, of the 231 children discharged from medical units between January and March 2017, 100 returned to their families, one was placed with the extended family, 7 were placed with other families/persons and 102 were placed in foster care.

At the same time, 6 children were placed in placement centers, 4 children were placed in emergency reception centers, and 11 children are in other situations, according to ANPDCA, quoted by Agerpres.

Almost 1,000 children (977 to be exact) were abandoned in Romanian hospitals last year. More than half of them have been left in maternity wards. This results from data centralized by the National Authority for the Protection of Children’s Rights and Adoption (ANPDCA).[image error]

August 30, 2017

The Romanian Boy Who Overcame The Dark Side of International Adoption

by Diana Mesesan

Nicolae Burcea got smallpox immediately after arriving in the US in 2002. He was sick in bed, looking out the window in a nice neighborhood. The 8-year old boy felt uncertain where the future was gonna lay, but it was the best feeling of being uncertain- to go to bed and not to worry about when you’re gonna be beaten up, when your food is gonna be stolen. It was a big relief. But of course, only for so long.

In his early childhood, he was Nicolae Burcea, but friends called him Nicu. After being adopted, the boy’s name became Nicolae Butler, and everybody in the US called him Nico.

The 23-year old man now uses Nicolae Burcea when he writes books or in casual conversations, but he’s still a Butler in official documents. Officially, though, he’s no longer a member of the Butler family.

“I like to think about it, to say that I’m a new generation Charles Dickens character because everything is an up and down. (…) The amount of luck I get is incredible especially given the odds,” says Nicolae.

In a hours-long Skype interview, Nicolae tries to disentangle his life story, to explain it to a stranger. It’s not the first time. He’s written a book about his early childhood in orphanages in Romania and he’s told his story hundreds of times. But despite the suffering, the young man feels that there could be a meaning, that his story could inspire others.

Nicolae Burcea was born in December 1993 and placed in the “Sfanta Ecaterina” foster care center in Bucharest’s District 1, according to his adoption papers.

Nicolae remembers a room full of cribs, everybody crying, car horns from outside, sitting in a room forever, and nobody coming to the room.

He wrote a book about his early years called “Memories of Childhood: Life in the Romanian Orphanages”. The book has a small poem as a dedication.

“These Memoirs are dedicated to

My biological and adoptive mothers,

So that you will know a part

Of my life that you never experienced with me.”

Nicolae now lives in Berlin, where he’s enrolled in a master’s program at the Institute for Cultural Diplomacy. He hasn’t yet visited Romania, but when he comes to Bucharest, he first wants to visit the “Sfanta Ecaterina” foster care center. The center no longer exists; instead, it hosts the headquarters of the District 1’s General Directorate for Social Assistance and Child Protection.

The “Sfanta Ecaterina” foster care was closed before Romania joined the EU, as part of a large deinstitutionalization process. The institution was shut down and replaced with three alternative services, with pre-accessing EU funds of over EUR 1 million.

The orphanage was synonym to abuses, from getting whipped to being sexually abused by the other kids. Caretakers played a role, but it was a vicious circle, says Nicolae. Caretakers were cruel to kids, who became abusers. “The orphanage is viciously making people abuse others and themselves,” he adds.

When asked if it’s not too disturbing to talk about these things, Nicolae replies immediately:

“Not an issue. I think for me the abuse has been so much and I am so used to it that I’ve become detached from it,” Nicolae says.

Around 2000, a family of wealthy engineers from Missouri, US, started the process to adopt Nicolae, who was from a Roma family. Most of the people prefer to adopt babies, but this family wanted to give a chance to an older boy.

His adoption papers include a report drafted by the Sperante foundation, which describes Nicolae’s mental and emotional development.

“The language is normally developed, the vocabulary is well represented, he uses complex sentences and can reproduce short poems. (…) He is emotionally balanced and has a proper social behavior,” reads the report.

Nicolae was healthy and went to school. “For my parents, I was like the perfect kid. In the US they all think all these kids just need a loving home and they’ll be perfect. It’s a lot of myth and I guess good selling from the people at adoption agencies,” Nicolae says.

The adoption process took forever, but a final decision came in April 2002. The document certified that the adoption of Nicolae Viorel Burcea was carried out according to the law.

By June 2002, Nicolae had his first bedroom ever, in a white neighborhood in the Saint Louis area, in the Missouri state. He was eight and a half.

“For me, when I was adopted was like the best moment. Because I was like the most important guy. You come from a place where you are nobody and suddenly you are the most important person in that family,” says Nicolae.

Nicolae in Romania

Nicolae in RomaniaHis adoptive family was a very caring and loving one, especially his dad. His mom used to dream about adopting a kid since she was a little girl.

“I had everything,” says Nicolae.

It seemed like a fairy tale, but things didn’t go as planned.

Nicolae was not easy to handle. In school, he got suspended many times. He was aggressive, talking back to teachers, showing high defiance, not following orders. He once punched a disabled guy when the boy took his soccer ball and refused to give it back to him.

School was tough.

“People look at you and you have dark skin and your parents are white skin. How did this happen? This obviously makes you feel pretty awkward. Especially because I went to very white communities,” Nicolae says.

He’d have to explain that he had been in an orphanage. People would sympathize with it. But to him this was bad.

“Nobody gives me anything because I deserve or because I earn it. They always give it to me because they sympathize and this makes you feel less of a human when you are being victimized not by yourself but by all the people who are surrounding you,” Nicolae explains.

The boy suffered from reactive attachment disorder, a very rare disorder in which kids don’t establish healthy attachments with parents.

“Parents didn’t treat their kids right, didn’t love them and eventually you get people who are incapable of loving others. And when people show love, it’s seen as a threat,” Nicolae says.

He found it difficult to adapt to an organized, rule-driven family, after years of chaos in orphanages. The rules felt as authority, and he had been traumatized by abusive authority in his past.

“I felt that my power was being taken away from me. When somebody said ‘go to bed at this hour’, I was like: I don’t want to do that. The authority felt very much like the orphanage in that sense.”

His parents became obsessed with fixing him, took him to several therapists, put him on medication. The situation at home got pretty bad. Nicolae felt that he was cast in the troublemaker role and that no matter what he’d do, he’d be different from the rest of the family.

“I became this super obscene, super trouble kid who cannot work in this very nice loving family,” Nicolae says.

Nicolae tells the story as if he was the bad character who failed. This tendency stems from his first years in the foster care system, he explains.

“You are kind of taught to take the blame when you are in foster care. Why are you there? Why would a normal family put you there?”.

But things were more complex. His family had the money, the lifestyle, but they had no patience, they had no time, they were stubborn, very engineer- minded, Nicolae adds.

All the therapists would tell them to stop thinking of a kid as something that you could fix. “This is a kid who has been through a lot, is working through a lot. You can’t compare him to his brothers.” Nicolae remembers that his parents would lock him in his room for hours, for days.

He thinks that his parents were people who had never experienced big trauma in their lives, who wanted to help but weren’t prepared to deal with a traumatized kid, who was far from perfect.

Every night he would always ask them “Even if I’m a terrible kid would you give up someone like me?” That became a ritual, something he would do every night. And every night the parents would say “We love you till everything, never will we give you up.”

The constant fear that he could be abandoned again was there all the time.

***

Dealing with Nicolae created a rift in the family. His grandparents had one way of thinking how to take care of the kids and his mom had another. Nicolae remembers a summer trip to Florida when he was 12.

They got into a fight over Nicolae. His grandparents told the parents that Nicolae was just a kid, that he just wanted to go to the beach and have fun. “Leave him be. You don’t have to be so restrictive, always think that he’s no good. He may be, but not all the time. Kids are kids,” Nicolae remembers his grandparents saying.

Things continued to escalate. At 16, there was an incident when Nicolae became physical with his parents and he had a fight with his dad.

“My dad told me something and it came to me as very aggressive, at least verbally and I immediately stroke back. This was after the situation at home got really bad,” he says.

His parents called the police. The officer took Nicolae to a medical center, which is what happens if you don’t know where to put kids and you don’t want to put them in jail, Nicolae explains. After a few days, his parents had to pick him up.

They came to the medical center, only to drop him off in an institution two hours later. They went to the court a few weeks later and gave Nicolae up to the state.

“I think it’s a fairytale gone wrong for them. I think it’s literally a German fairy tale on a grim side,” Nicolae explains. “They never got what they wanted. They wanted a kid who loved them, followed their rules, a kid they could react to. I wasn’t that way.”

Then he adds: “This is just what happens. This is just the dark side of adoptions gone wrong.”

***

Nicolae now lives in Berlin, but spends the summer in London. People have often told him while he was abroad: “Oh my God, you come from America; please tell me how awesome it is. How great it is.”

Not only that he got the bad end of America in sense of family, but he also got the worst of it in the sense of where unwanted kids go, Nicolae says.

At 16, Nicolae became one of the United States of America’s unwanted kids.

In 2015, there were about 428,000 kids in the US foster care system, according to US official statistics.

“You get the kids who are unwanted and you get the kids who are high abusers. (…) Their lives are ruined. There is no other way of saying it. Many kids, two-thirds of us, would end up in jail. That’s what we were told. It was just a fact of life,” Nicolae says.

When he entered the foster care system, he went from being a terrible kid to a great kid. He had more freedom, he could dictate his plan based on his behavior. This was in the beginning. After some months, he became really frustrated about the system’s immovability. The education was terrible, nobody cared about you. He was scared to remain in the same institution for years, so he tried to force the system. The only way to move forward was to get expelled.

Nicolae moved to several schools and different levels of the foster care system. Meanwhile, his former adoptive parents were still in touch with him, although they were no longer his parents. This felt like a pressure for Nicolae. Once they relaxed their grip on him, Nicolae started improving. He decided to prepare himself for college. He read everything that he could find, wrote a lot.

At 21, the state gave him up, and his grandparents stepped more into the picture. They helped him pay for the college.

“We’ve always thought that he was very smart and he’s always wanted to go to college very badly so we’ve helped him with finances although he got some grants,” says his grandmother Velma. “If it didn’t work out it didn’t work out, but at least we felt that he had a chance.”

Nicolae joined a fraternity, became the school vice president, played football, had two jobs. He managed to do four years of college in two years. Nicolae’s good results weren’t a surprise for his grandparents.

“We were expecting that because he would read anything he could get his hands on,” says Velma.

“He knew a lot more about the US Government than I did,” adds his grandfather Marion.

After college, Nicolae came to Europe, where he’s currently in a master’s program in international relations.

One of his teachers recently asked him if he felt that he belonged anywhere. He doesn’t feel American, nor Romanian, but he’d like to come to Romania someday and do something big here; maybe even run for the president office someday. Many people have told him that it’s a crazy dream, but Nicolae says that he doesn’t want a simple life. He wants to inspire people, to change Romania’s image abroad.

“I would say my parents never left me so much room to kind of do things on my own. They thought I was a kid, treated me as a kid, never let me do things independently. This caused a rift in the family. It just became a psychological battle between me and them. When I had the freedom to do what I could do, all I had to do was show people: look, I am an exceptional kid.”

By Diana Mesesan, features writer, diana@romania-insider.com

August 25, 2017

Mums Who Hold Their Tempers Hold The Key

Health

Psychology

Mums who hold their tempers, hold the key

Mums who hold their tempers, hold the key

By MiNDFOOD | APRIL 14, 2014

Children of highly educated mothers who keep a clean home and can hold their tempers, are less likely to develop behavioural problems, a new study has found.

It would seem as though mothers once again shoulder the burden when it comes to links between family income and child potential according to the new study, “Child Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Development: Does Money Matter?

“For a long time there has been a consensus that there is a connection between family income and child health, child cognitive and non-cognitive development,” said Dr Rasheda Khanam, the USQ Senior Economic Lecturer who led the study.

“But the mother’s outlook, how she raises her children, and the home environment she provides – reading with her children, taking them to the cinema, playground or sporting events, providing a clean, organised home – have not been included in previous studies.

“What we wanted to do was look at the pathways that make this connection between family income and child development to get the story behind this well-established link.”

Dr Khanam took a new approach, combining for the first time economists’ and psychologists’ views in modelling the relationship between income and child development outcomes.

Using data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children –– she found that a mother’s mental health, and stress levels were crucial in ensuring her children were less hyperactive or had less emotional, behavioural or peer problems.

“What we found is that family stress – that is parenting styles and the mother’s mental health and parental investment capacity– are extremely important in child emotional and behavioural development,” Dr Khanam said.

“A mother who had a ‘warm parenting style’, who invested in her children, who gave them access to books and computers, could bridge the income-potential gap, with love and time.”

Dr Khanam said it was the education standard and input of the mother that found to be more significant than fathers in the study, as women were still the primary carers.

However, fathers were not completely discounted in fact dads with “warm parenting styles” helped their children develop higher reasoning skills; while mums and dads who stayed together were less likely to raise children with behavioural issues.

The study also found depressed parents were more likely to produce children with poorer math scores, while those from low income families were more likely to be hyperactive.

“We found children from lower income households were more likely to be unable to stay still and were easily distracted, with poor concentration and memory,” Dr Khanam said.

“They often acted without thinking.”

Dr Khanam said while income was important for cognitive development, the ground breaking study found when it came to non-cognitive development, mothers were key.

“We didn’t have the story behind the link between household incomes and child potential, and now we do – those who have a higher income tend to have mothers with a higher education who practice better parenting skills, resulting in lower mental stress on the family, and better relationships,” she said.

“In other words, if you have a good income, you can live in a better house in a good environment with lots of books for your children, and all in all, you will have more of an idea as to how to raise your children.

“So what is needed is to get more systems in place to educate parents, to teach them to correct their children where needed yet at the same time show them affection, hug their children, invest in their children and start having conversations with them.

“If you don’t have the income but you invest the time, you can breach the gap.

August 7, 2017

Intercountry Adoption Australia; Ad hoc Adoptions

UNCLASSIFIED 18/11/14

Dear Adele

Our department is the Australian central authority for intercountry adoption under the Hague Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in respect of Intercountry Adoption. We are responsible for the establishment and management of Australia’s intercountry adoption arrangements, and for related policy. We work closely with the state and territory central authorities, which are responsible for the delivery of adoption services, including the assessment and approval of individual intercountry adoption applications.

As you note in your letter, Romania is currently only accepting intercountry adoption applications from Romanian citizens and from relatives (within the fourth degree of kinship to the child for whom a domestic adoption proceeding has been approved). Under Australia’s current intercountry adoption arrangements, applicants who fulfil these requirements may already apply to adopt from Romania through either the relative adoption or ad hoc adoption processes. In both cases, applicants must fulfil the requirements set by their state or territory central authority and Romanian authorities, and their state or territory central authority must agree to facilitate the adoption. Applications for ad hoc and relative adoptions are considered by state and territory central authorities on a case-by-case basis.

Australians with Romanian citizenship who wish to adopt a child from Romania may consider submitting an ad hoc adoption request. Ad hoc requests refer to applications to adopt a child from a country Australia does not have a programme with, but where the applicants can demonstrate a significant link to the country of origin (including Australians adopted from Romania). A fact sheet about the ad hoc adoption process is available on our website: Intercountry adoption policies and key documents).

Australians who wish to adopt a relative child from Romania may consider submitting a relative adoption application. The fact sheet (also available on our website) provides more detail about the relative adoption process.

The first step in both processes is for prospective adoptive parents to contact their local state or territory central authority. Contact details for the state and territory central authorities can be found on the Australian, state and territory central authorities page of our website.

Australian Families for Children is currently accredited to provide specific intercountry adoption services in NSW, including training prospective adoptive parents, assessment of the suitability of persons to adopt a non-citizen child, and post-placement support. AFC is not currently authorised to provide intercountry adoption services in overseas countries.

Thank you again for writing to us on this matter.

Kind regards

Josh

______________________________________________________

Intercountry Adoption | Access to Justice Division

Australian Government Attorney-General’s Department

National Circuit | Barton ACT 2600

Tel +61 2 6141 3217 | Fax +61 2 6141 324

Associata Catharsis- Adoption Agency. Adoption and Disability Advocacy.

The President of Romania has sent a signed decree to parliament promoting some changes to the adoption law. adopției.

The adoption law, although said to be “new”, is in fact the “old” law with some minor changes. But the lack of transparency and the discriminatory nature of the law currently in force has not been changed. That law, nr.273/2004 has been very slightly modified three times since 2004: in 2009, in 2011, and in 2015. And all of that was due to pressures from society as a whole.

The modifications made by the National Authority for the Protection of the Rights of the Child and for Adoption have not really modified anything substantive, including adjustments made in April of 2015. Those adjustments really did nothing in favor of the children who find themselves “imprisoned” [apart from a permanent family] since the day that they were born.

There is really no hope for a permanent family for more than 23,000 institutionalized children in approximately 1500 placement centers. The new legislation really does not offer them one bit of hope.

The modifications do NOT foresee a way to truly reduce the number of institutionalized children, but rather foresees only a reduction in the time frame of adoption and also a leave time for parents to get to know the adopted child.

The modifications also allow for a subsidy of 1700 lei per month (about $425) for a time period of 1 year for one of the parents who adopt a child over the age of two years. And that’s about it.

The law continues to discriminate against children for whom a family in Romania or for whom a Romanian family cannot be found. Usually this has to do with the health of the child, the child’s ethnicity, and/or the child’s age.

The adoption law also continues to discriminate against Romanian families and non-Romanian families who live in countries that are signatories to the Hague Convention. The adoption law currently requires either Romanian citizenship, or the establishment/reestablishment of residence in Romania, i.e., to live continually in the country/territory of Romania in order to receive the evaluations and attestations necessary to adopt.

The adoption law does NOT in any way guarantee every child’s right, and particularly the right of abandoned children, to a permanent family in which to grow up.

We will protest these injustices even in the streets of Romania, and we will militate for the rights of these children.

July 15 – 2017

Alături de Caty Roos, psiholog și Silvia Tișcă, asistent social, alte 12 familii au finalizat cursul de formare a calităților parentale și au primit deja Atestatul de familie aptă să adopte un copil. Pregătim părinți, oameni minunați, pentru copii speciali.

Along with Caty Roos, psychologist and Silvia Tișcă, social worker, 12 other families completed the parenting training course and they already received the family attestation fit to adopt a child. We’re setting up parents, wonderful people, special kids.