Stephen D. Morrison's Blog, page 9

November 17, 2016

The Best of #Barth21 – My Favorite Quotes from CD II/1 (Karl Barth)

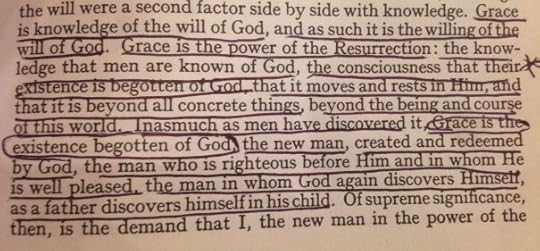

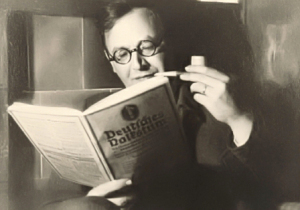

Over the last month I’ve been reading Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics volume II/1 and posting quotes with the hashtag #Barth21 on my Facebook and Twitter pages. I did this once before over the summer when I read Barth’s Epistle to the Romans (you can find the wrap up here). I hope everyone who follows me on social media enjoyed reading these short quotes from Barth’s brilliant volume.

Over the last month I’ve been reading Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics volume II/1 and posting quotes with the hashtag #Barth21 on my Facebook and Twitter pages. I did this once before over the summer when I read Barth’s Epistle to the Romans (you can find the wrap up here). I hope everyone who follows me on social media enjoyed reading these short quotes from Barth’s brilliant volume.

Today as a wrap up I’ll share some of my favorite quotes from this volume. Enjoy! (Direct quotes are in quotations, personal reflections are indicated.)

#Barth21

“Here [in CD II/1] we have the basis upon which the whole of Barth’s teaching rests…” [Editors Preface]

“We can only understand how God is knowable from the way He actually gives Himself to be known.” [Editors Preface]

“The self-knowledge of God is the real and primary essence of all knowledge of God.”

“God never ceases to make continual new beginnings with men [and women].”

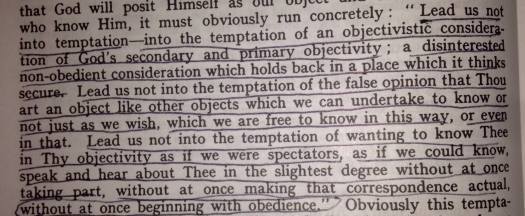

Lead us not into temptation…

“The being of God is either known by grace or it is not known at all.”

The knowledge of God—theology—cannot take place in a vacuum. To know God is to be related to God in obedience and love. [My own personal reflections while reading, #reflections]

“God is known through God and through God alone.”

“When God speaks about Himself, He speaks about the fact that He is the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.”

“God knows Himself… This is the essence and strength of our knowledge of God.”

“Our knowledge of God is derived and secondary. It is effected by grace…”

“It is by the grace of God that God is knowable to us.”

In natural theology “we are not dealing with God but at bottom with ourselves.”

Redemption “means that Jesus Christ is coming again. It means the resurrection of the flesh. It means eternal life…”

“None of the writings of Anselm are ‘apologetic’ in the modern sense of the concept.”

You know you’ve been reading a lot of Karl Barth when a single paragraph is five pages long and that doesn’t surprise you! [#Reflections]

“Man[kind] exists in Jesus Christ and in Him alone, as he also finds God in Jesus Christ and in Him alone.”

“Jesus is the knowability of God on our side…He is the grace of God…and therefore also the knowability of God on God’s side.”

“Our enmity, the enmity in which man as such stands against grace, is expiated and abandoned before God by God Himself.”

“The enmity of man against God is annulled, done away, obliterated.”

“In Jesus Christ God has taken man[kind]’s affairs out of his hands and made them His own affair.”

Christian theology “is wholly and utterly the prisoner of its own theme, namely, the Word of God spoken in Jesus Christ”

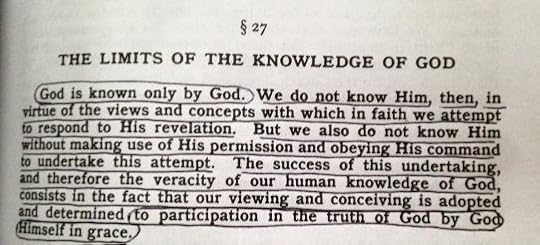

§27…

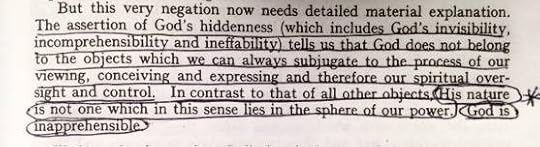

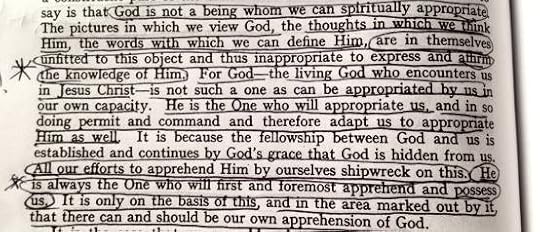

What is the hiddenness of God?

God cannot be spiritually appropriated…

The hiddenness of God “affirms that our cognizance of God does not begin in ourselves.”

“At best, our theology is theologia viatorum [theology ‘on the way’].”

“The Gospel rightly seen and understood is always the victorious Gospel.”

“God is who He is in His works.”

“Subject, predicate and object; the revealer, the act of revelation, the revealed; Father, Son and Holy Spirit.”

“God exists in His act. God is His own decision. God lives from and by Himself.”

“God is He who, without having to do so, seeks and creates fellowship between Himself and us.”

“[God] does not will to be without us, and He does not will that we should be without Him.”

“God does not exist in solitude but in fellowship.”

“Loving us, God does not give us something, but Himself; and giving us Himself, giving us His Son, He gives us everything.”

“The kingdom of God is not an independent reality… This kingdom cannot in any sense be separated from its King.”

“[God] loves us and the world as He who would still be One who loves without us and without the world.”

“God’s being as He who lives and loves is being in freedom.”

“We cannot get behind God—behind God in His revelation [Jesus Christ]—to try and determine from outside what He is.”

“The fundamental error of the whole earlier doctrine of God is reflected in this arrangement: first God’s being in general, then His Triune nature.”

“Grace is the very essence of the being of God.”

“The impassibility of God cannot in any case mean that it is impossible for Him to feel compassion.”

“God cannot be compared to anyone or anything. He is only like Himself.”

“God’s love is divine as the love which is free.”

“God is simple. …[which means] in all that He is and does, He is wholly and undividedly Himself.”

For Barth, God’s omnipresence doesn’t mean metaphysical “eternity”, but God’s triunity, God’s freedom to be present to another. [#Reflections]

“God can be present to another. This is His freedom. For He is present to Himself.”

“There is nowhere where God is not, but He is not nowhere. …He is always somewhere—seeking man[kind] and there to be sought.”

“There is no non-presence of God in His creation.”

“God is constant.”

“[God’s true] immutability includes rather than excludes life. In a word it is life.”

Because “immutability” often implies an immobile state of death, a state incongruent with the living God, Barth thinks “constancy” is a far better term whenever speaking of God’s being in freedom. [#Reflections]

“By God the world exists in God.”

“In the investigation and knowledge of the constant will and being of God we cannot go behind Jesus Christ.”

“God is ‘immutably’ the One whose reality is seen in His condescension in Jesus Christ… He is not a God who is what He is in a majesty behind this condescension, behind the cross on Golgotha.”

Divine omnipotence ≠ divine omnicausality. [#Reflections]

“God’s love for us does not simply mean that He knows us; it means also that He chooses us.”

“God is His own will, and He wills His own being.”

“Pelagianism and fatalism are alike heathen atavisms in a Christian doctrine of God.”

From the standpoint of the incarnation “we cannot understand God’s eternity as pure timelessness.”

“God is pre-temporal. God is supra-temporal. God is post-temporal.”

God “is in Himself, and therefore to everything outside Himself, relationship, the basis and prototype of all relationship.”

“God is the One who seeks and finds fellowship.”

“God is glorious in such a way that He radiates joy.”

“We can confidently say that [theology] is the most beautiful of all the sciences.”

“The theologian who has no joy in his work is not a theologian at all. Sulky faces, morose thoughts and boring ways of speaking are intolerable in this science.”

“If we deny [the Trinity], we have a God without radiance and without joy (and without humour!); a God without beauty.”

“To believe in Jesus Christ means to become thankful.”

“God gives Himself to the creature. This is His glory revealed in Jesus Christ, and this is therefore the sum of the whole doctrine of God.”

I enjoyed posting these quotes and engaging with readers along the way as I read Barth’s classic volume II/1 from the Church Dogmatics. Thanks everyone for reading, retweeting, and liking these posts!

Like this article? Share it!

November 13, 2016

“God Joins the Army” – A Modern Day Parable by Peter Rollins

It’d be an understatement to say this week has been a devastating one in America, for many Americans and for many reasons. I wanted to share a story I often found myself thinking about, a “modern day parable” if you will. It comes from Peter Rollins’ great little book The Orthodox Heretic. It’s brought me comfort in these conflicting times, and I hope it does the same for you.

It’d be an understatement to say this week has been a devastating one in America, for many Americans and for many reasons. I wanted to share a story I often found myself thinking about, a “modern day parable” if you will. It comes from Peter Rollins’ great little book The Orthodox Heretic. It’s brought me comfort in these conflicting times, and I hope it does the same for you.

“Many centuries ago an independent island was attacked by the dictator of a nearby nation, a nation with vast resources and a mighty army. Upon landing on the island, this army moved with little resistance toward the capital city. With less than a day to decide what action to take, the leaders of the island desperately discussed what could be done in the face of the encroaching army. They were hugely outnumbered, out-resourced, and out-skilled, so defeat seemed inevitable.

The leaders never made a decision without first consulting with their religious oracle, so they approached her small dwelling on the edge of the city. The oracle was a woman who possessed great insight and had the ability to see into realms usually reserved only for the angels. Upon hearing about the invasion, she spent an entire day in deep meditation before finally coming to the leaders with a heavy heart, saying,

‘I bring sad news: I have been told that God himself has joined with our enemies and has put all of his power at their disposal.’

This ominous message sent deep fear and trembling through the hearts of the elders. In response one proclaimed, ‘We must surrender now and pray that they will have mercy on us.’ Then another responded, ‘No, let us make ready our fastest ships and set sail with as many people as we can. Perhaps we can sneak past their navy while it is dark.’ But the chief, a strong man with deep faith, remained calm throughout the debate. At the end of the discussion he said, ‘Please trust me, I know what to do in order to ensure that we make it through this dark hour.’

The chief was well respected by all, and so, in absence of a plan, they reluctantly agreed to trust him.

That day he called together all the men of the city who could fight. He then sent those with young children home, followed by those who had been married for less than a year. By the end of this process the remaining men numbered less than a few thousand, a tiny group in comparison to the army they would soon face.

These brave men were then armed and told to march behind their chief toward the encroaching army. That day there was a bloody battle and many tragically lost their lives. But, to everyone’s utter surprise, by the end of the day the dictator’s seemingly impenetrable army had been dealt a devastating blow and had turned away in retreat.

The entire island was dumbstruck as they heard how the enemy had run in fear and trembling back to their homeland. The oracle however was more confused than most, for she knew what had been kept secret from the people: that God had joined the side of the enemy and put all his vast power at their disposal. So the oracle approached the chief and said, ‘How did you know to fight when the odds where impossibly high and when you knew that God himself was pitted against you?’

But the chief merely smiled and replied, ‘Surely you know that it does not matter which side God is on. When God is involved, the oppressed always win.'”

(Peter Rollins, The Orthodox Heretic, pp 111-3)

Like this article? Share it!

October 21, 2016

Karl Barth on “God is Love”

As those of you who follow me on either Facebook or Twitter know, I am currently reading Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics volume II/1 and posting some of my favorite quotes along the way with the hashtag #Barth21. I hope you’ve enjoyed following along so far through this magnificent book. I’m about 33% of the way through, so there are still plenty of great quotes to come.

As those of you who follow me on either Facebook or Twitter know, I am currently reading Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics volume II/1 and posting some of my favorite quotes along the way with the hashtag #Barth21. I hope you’ve enjoyed following along so far through this magnificent book. I’m about 33% of the way through, so there are still plenty of great quotes to come.

I wanted to share an extended quote I read today in which Barth discusses the being of God as the One who loves. This is a beautiful section, containing many great insights. Enjoy!

(Quotes are from the Hendrickson Publishers 2010 edition. Italics are original; bold is mine.)

Karl Barth on “God is Love”

“God is He who, without having to do so, seeks and creates fellowship between Himself and us.” (273)

“[God] wills to be ours, and He wills that we should be His. He wills to belong to us and He wills that we should belong to Him. He does not will to be without us, and He does not will that we should be without Him. He wills certainly to be God and He does not will that we should be God. But He does not will to be God for Himself nor as God to be alone with Himself. He wills as God to be for us and with us who are not God. …He does not will to be Himself in any other way than He is in this relationship. His life, that is, His life in Himself, which is originally and properly the one and only life, leans towards this unity with our life. The blessings of His Godhead are so great that they overflow as blessings to us, who are not God. This is God’s conduct towards us in virtue of His revelation.” (274)

I love this! God is so for the human race that God wills not only to be God in Himself, but, without having to do so, God becomes our God and makes us His people. This is the depths of God’s love for us. These statements come after Barth works through the concept of God’s being in God’s act, of God as the “self-moved” God. Accordingly, who God is towards us is who God is in Himself, God’s act is God’s being. God loving us is therefore not just a part of who God is or a part of what God has done for us, God loving us is who God is, God is this God, the God who wills not to be God without us, who wills us not to be human beings without Him.

From this Barth continues, explaining that God is this way in Himself, that God is not a solitary, or lonely being, but that God is a fellowship in Himself. In other words, that God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

“As and before God seeks and creates fellowship with us, He wills and completes this fellowship in Himself. In Himself He does not will to exist for Himself, to exist alone. On the contrary, He is Father, Son and Holy Spirit and therefore alive in His unique being with and for and in another. The unbroken unity of His being, knowledge and will is at the same time an act of deliberation, decision and intercourse. He does not exist in solitude but in fellowship. Therefore what He seeks and creates between Himself and us is in fact nothing else but what He wills and completes and therefore is in Himself. It therefore follows that as He receives us through His Son into His fellowship with Himself, this is the one necessity, salvation, and blessing for us, than which there is no greater blessing—no greater, because God has nothing higher than this to give, namely Himself; because in giving us Himself, He has given us every blessing. We recognize and appreciate this blessing when we describe God’s being more specifically in the statement that He is the One who loves. That He is God—the Godhead of God—consists in the fact that He loves, and it is the expression of His loving that He seeks and creates fellowship with us. It is correct and important in this connexion to say emphatically His loving, i.e., His act as that of the One who loves.” (275)

It is because God is in Himself this fellowship, is in Himself the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, that God creates fellowship with us. God’s blessing to us is His giving us the highest good: Himself. It’s because God is this God in Himself that God loves us and creates fellowship with us. God could not love us or have fellowship with us if God were not in Himself love and fellowship, thus God must be this Triune God in the loving fellowship of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. A unitarian God, a solitary God, cannot love or be in fellowship with another. Only the Triune God can properly love out of His very being and nature. 1

From this Barth moves to an exegesis of that famous passage in 1 John 4:8, “God is love.” Barth brilliantly notes that the context of this verse gives far more meaning to it than the phrase is often given. We tend to shortchange the idea that God is love when we forget the context this statement comes in. Barth explains:

“The tempting definition that ‘God is love’ seems to have some possible support in 1 Jn. 4:8. But it is a forced exegesis to cite this sentence apart from its context and without the interpretation that is placed on it by its context, and to use it as the basis of a definition. We read in v. 9: ‘In this was manifested the love of God towards us, because that God sent his only begotten Son into the world, that we might live through him.’ Again we are told in v. 10 (with a remarkable similarity of prediction): ‘Herein is love, not that we loved God, but that he loved us, and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins.’ And finally in v. 15: In this we have knowledge and faith in the love that God has for us, that we confess ‘that Jesus is the Son of God.’ The love of God, or God as love, is therefore interpreted in 1 Jn. 4 as the completed act of divine loving in sending Jesus Christ.” (275)

We tend to quote the phrase “God is love” and misuse it as a kind of abstract definition we can fulfill. We say God is love but then we define love ourselves, making God into whatever we’d like Him to be. But here Barth insists upon saying that this means, properly, that God has sent Jesus Christ for our sakes. John 3:16 also defines love in this way; that God loves means that God sends His Son for our sakes. God’s love is not an abstract definition we can fill with whatever we want to say, defining it by ourselves. God’s love is God’s definition, and only God can define it, and has, in sending Jesus Christ for our sakes.

Conclusion

In these quotes Barth has brilliantly and beautifully painted a picture of God as the One who loves, the One who wills not to be God without us. This may be one of my new favorite Barth quotes! I hope you’ve enjoyed it as well.

Keep following along with #Barth21 by liking my Facebook page and following me on Twitter. Cheers!

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

This is a point I bring up in the first chapter of my book, We Belong: Trinitarian Good News. Check it out for more. ↩September 25, 2016

4 Traits that Made Karl Barth a Great Theologian (According to T F Torrance)

Yesterday I began reading Thomas F Torrance’s book, Karl Barth: An Introduction to His Early Theology 1910-1931. I first read Barth because I had read and enjoyed Torrance, so it’s an understatement to say I’ve been excited to dive in and learn what Torrance has to say about Barth. (So far it’s been a great book.)

Yesterday I began reading Thomas F Torrance’s book, Karl Barth: An Introduction to His Early Theology 1910-1931. I first read Barth because I had read and enjoyed Torrance, so it’s an understatement to say I’ve been excited to dive in and learn what Torrance has to say about Barth. (So far it’s been a great book.)

Torrance writes of four traits (personal characteristics) which made Barth a great theologian. Today I wanted to repeat these traits to you, as they are all great traits we can learn from. Enjoy!

#1 An Inquisitive Mind

Torrance writes, “Barth has the most searching, questioning mind I have ever known.” 1 This would be apparent to anyone who has ever read, for example, in the Church Dogmatics, the pages upon pages of questions Barth asked. Torrance estimates that if you were to put only the questions asked in the Dogmatics into a book it would fill “hundreds of hundreds of pages.” Barth asked a lot of questions!

But Barth’s ruthless questioning is not the same kind as the questioning other theologians have done, such as the questions found in Paul Tillich’s method of correlation. (More on Barth and Tillich here.) Barth’s questions are a ruthless criticism for the sake of letting the Word of God speak clearly and positively to us. These questions seek to self-critically clear the way for God’s Word to speak.

Torrance writes, “This questioning is forced upon us because face to face with God’s Word we know ourselves to be questioned down to the very roots of our being, and therefore in response to the impact of the Word we are thrown back upon self-criticism, upon a repentant questioning and rethinking of all that we have and are and claim to know.” 2 We ask questions because God’s Word has confronted us to the core of our being. We must ask questions to make a way for the Word of God to speak clearly and positively to us, to rightly hear the content of this Word. These questions seek to remove our presuppositions (or at least limit them).

We ask questions forcefully and ruthlessly, then, not because God is bound to our questions, but because God has confronted us and this demands us to question our reality and make room for the Word of God to speak. This is the sort of questioning which is rooted in a deep humility before the truth of God, a truth which lies beyond our grasp and which meets us only by grace.

#2 A Childlike Willingness to Learn and Listen

Torrance writes, “Barth has an uncanny ability to listen which is accompanied by an astonishing humility and childlikeness in which he is always ready to learn.” 3 Torrance calls this “the secret of Barth’s hermeneutics, whether he is interpreting Holy Scripture or interpreting the thought of another theologian.” 4

Barth listened and listened well to the great theologians of the church, and his critical appreciation of their work always came first and foremost from this place of listening. But this is not only how Barth read other theologians; this is Barth’s method for biblical exegesis.

Torrance notes, “Biblical exegesis takes place therefore in a strenuous disciplined attempt to lay ourselves open to hear the Word of God speaking to us, to read what the Word intends or denotes and to refrain from interrupting it or confusing it with our own speaking, for in faithful exegesis we have to let ourselves be told what we cannot tell ourselves.” 5

This is a lesson we can all apply for reading not only the bible and other theologians, but even Barth’s work, too. Critics like Van Til have always failed in this regard, they have failed to listen to Barth on his own terms. We will always fail to understand the bible, to understand what God is speaking to us in the Word of God, and we will always fail to understand Barth, when we fail to listen.

#3 Creativity

Torrance writes, “Another typical characteristic of Barth which we must give attention is his sheer creative power, his ability to produce something new.” 6 Torrance likens Barth to Beethoven. Beethoven is a shocking composer who often merged together various themes which, at first, seem contradictory, but which ultimately enrich the whole symphony with a multi-faceted kind of beauty. Barth might not like this analogy (he preferred Mozart), but it aptly applies to Barth’s ability to create something shocking and beautiful in his Dogmatics. It takes a creative genius to do what Barth has done in the Church Dogmatics, and I doubt anyone who reads it with the care it demands would fail to see its genius.

Interestingly, Torrance writes here what he considers to be Barth’s main theological theme: “From first to last Barth’s main theme has been the turning of God in utter grace in incredible condescension to man to be man’s God, so that what we are concerned with in the Gospel is the sovereign togetherness of God with man and the exaltation of man to share in the divine life and love.” 7

I like that a lot! If I had to summarize what I have learned the most from Barth, personally and theologically, I couldn’t find a better summary than this.

#4 Joy

Torrance writes, “There is one other aspect of Barth, both as a man and as a theologian, which we must select for mention: his joy and his humour.” 8 One of my favorite quotes from Barth sums up this point well: “The theologian who labors without joy is not a theologian at all. Sulky faces, morose thoughts and boring ways of speaking are intolerable in this field.”

Torrance gives two examples of Barth’s joy and humor. First, he mentions Barth’s love of Mozart, and his elevating him to the status of “church father.” And second, Torrance notes a humorous comment from CD III/2, which says, “What a pity that none of these apologists consider it worthy of mention that man is apparently the only being accustomed to laugh and to smoke.” 9

Beyond these two points, Torrance notes that Barth writes with joy not because he is necessarily a joyful person, but because God is a God of supreme joy. It’s Barth’s doctrine of God, his enjoyment of the beauty and glory of God, which most establishes his joy as a theologian. Torrance calls Barth an exemplary theologian of the frui Deo, of the enjoyment of God. Joy is at the center of his theology, and anyone reading his work will find themselves confronted with the God of infinite joy.

Conclusions

There are a lot of theological insights we can learn from Barth, but Torrance reminds us that we can also learn from from how Barth practically lived and worked out his theology. Barth was not afraid of asking difficult questions, because God has first met us, at the core of our being, and questioned us in Jesus Christ. Barth was humble before the truth, and therefore willing to listen carefully to the testimony of the scriptures and to learn from other theologians. Barth was a creative genius, who worked tirelessly at constructing a new and innovative theology. Barth was a joyful and humorous person, because God is a joyful and humorous God.

In the spirit of Barth’s humanity, joy, and of his love for Mozart, I’ll leave you to enjoy three hours of Mozart’s Sonatas (or however long you want to listen). Cheers!

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Torrance, Karl Barth, 19 ↩Ibid. ↩Ibid., 21 ↩Ibid., 22 ↩Ibid. ↩Ibid., 22-23 ↩Ibid., 23 ↩Ibid. ↩CD III/2, 83 ↩September 24, 2016

The Book to End Penal Substitutionary Atonement

Penal substitutionary atonement is a theory which attempts to explain the meaning and purpose of Christ’s death, how Jesus’ death saves and what it means for the world. It’s a theory which I have argued against openly and often, I’ve written extensively against it in my book We Belong: Trinitarian Good News. Penal substitution is also the subject of the next two books I plan to publish in the near future, one which places Karl Barth in dialogue with the so-called “atonement debate,” and another to deal directly with penal substitution and argue against it. So it goes without saying: I am passionate about seeing an end of the penal substitutionary atonement theory in the evangelical church today.

Penal substitutionary atonement is a theory which attempts to explain the meaning and purpose of Christ’s death, how Jesus’ death saves and what it means for the world. It’s a theory which I have argued against openly and often, I’ve written extensively against it in my book We Belong: Trinitarian Good News. Penal substitution is also the subject of the next two books I plan to publish in the near future, one which places Karl Barth in dialogue with the so-called “atonement debate,” and another to deal directly with penal substitution and argue against it. So it goes without saying: I am passionate about seeing an end of the penal substitutionary atonement theory in the evangelical church today.

I recently finished reading a fantastic book, one of the best I’ve read this year (and I’ve read over 100 books so far!), which I believe may do exactly that: this book, I hope, will be the final nail in the coffin of penal substitutionary atonement. The book I’m referring to is Darrin W. Snyder Belousek’s Atonement, Justice, and Peace. This book is the most complete argument I have ever read against penal substitution, and it’s written in a clear, accessible manner so that anyone can pick it up and read it without much difficulty. Don’t be daunted by the fact that this is a 700 page book, this is a clearly written, accessible book that just about anyone with a basic understanding of the bible can read.

Today I simply want to recommend this book to you, discuss the main argument in it, and also briefly introduce penal substitution for anyone unfamiliar with it. I’ve never felt so encourage by a book on the atonement, and for that reason I give this book a whole hearted endorsement and I hope you take the time to read it.

What is Penal Substitution?

Penal substitution rest on three basic ideas. First and foremost, the notion of retributive justice, that God requires the death of a perfect sacrifice to forgive our sins. In short, that on the cross Jesus Christ died to pay back God’s justice. Second, that the wrath of God must be appeased, that God is full of wrath towards us and must have that wrath satisfied, or “propitiated” in Christ’s death. And finally, the third notion is that God turned His back on Jesus Christ in His death, that Jesus was forsaken and abandoned because God cannot look upon our sin.

Penal substitution is the most common atonement model within the evangelical church today. It’s often preached with the analogy of a courtroom. God is a holy judge, and we are the guilty sinners. God’s justice demands payment, demands our death, and therefore God’s wrath is against us until payment is made. We deserve punishment, but we are unable to pay back God’s justice or appease His wrath. But Jesus Christ came out of love for us and died in our place; God punished Jesus instead of us, thus paying back the Father’s justice, satisfying His wrath, and saving us from hell. God turned His back on Jesus Christ, and in forsaking Him, God now accepts us as His children. God’s wrath is appeased, God’s (retributive) justice is satisfied, and God can now accept us as His own. This is penal substitution: Jesus Christ is punished (penal) in our place (substitution).

Belousek’s Argument

There are many problems I have with this theory, many of which are far too time consuming to address here. Like I said, I plan to eventually put together a short book which contains a concise argument against penal substitution. But here I want to discuss the main argument in Belousek’s book against penal substitution.

Belousek brilliantly sees the foundational presupposition behind penal substitution to be the idea that God’s justice is retributive, that is, that God’s justice demands equal payment for an offense. In short, penal substitution rests upon the lex talionis, the “eye for an eye” of the levitical law. God’s justice demands our death as payment for sin, and God is bound by this kind of justice and thus cannot forgive our sins without payment. Thus Jesus suffers God’s punishment in our place, so that God’s wrath can be appease and we can be forgiven. But the question we have to ask is this: do the scriptures understand God’s justice in this way? Is the justice of God, revealed to us in Jesus Christ, a retributive kind of justice or a redemptive kind of justice?

Simply, the underlying presupposition of penal substitution, the foundation upon which the entire theory rests, is that God’s justice is retributive, that God’s justice demands payment for an offense, tit for tat.

Belousek argues, rightly, that God’s justice is not retributive. Jesus Himself argues against any “eye for an eye” sort of justice in the sermon on the mount. (Matthew 5:38-42) But penal substitutionary atonement basis its entire paradigm on this idea. Belousek thus carefully and thoughtfully takes us through the bible and shows us that this idea comes not from the scriptures but from Greek philosophy. Aristotle and Socrates, who in turn influenced Augustine and thus infiltrated the west with this idea, are the originators of this kind of justice. The scriptures actually have no concept of retributive justice (not even the lex talionis, Belousek argues, is God’s will). The only kind of justice we see in the scriptures is the justice of mercy, the justice which heals, the justice of redemption. The scriptures present a kind of justice that looks more like “making right what’s wrong” (redemptive justice) instead balancing the legal scales (retributive justice). Belousek brilliantly takes you through ever problematic scripture, from Isaiah 53, Romans 3, the levitical law, and the prophets, in order to show this point.

The beauty of this argument is in its successful identification and removal of the foundation of penal substitution; what remains for the rest of the book is the joyful and systematic demolition of this theory. There is nothing left standing by the end of this book. There is no scripture which has not been examined, there is no presupposition left hiding, penal substitution is effectively put to death. There is an elegance and a brilliance to Belousek’s argument, and I have not doubt that this book will be the end of penal substitutionary atonement for anyone who reads it—and hopefully for the evangelical church as a whole.

If you have ever doubted penal substitution, but then thought, what about Isaiah 53? What about Romans 3? Then please, read this book. Maybe you are someone who wholeheartedly believes penal substitution is the gospel, then please, read this book.

I cannot stress how highly I recommend Belousek’s book. Perhaps one day the church will look back to it and say, “This was the book that once and for all exposed and demolished the heretical penal substitutionary atonement theory!” You can purchase Atonement, Justice, and Peace here.

Like this article? Share it!

September 2, 2016

Theology of the Pain of God by Kazoh Kitamori (Book Review)

Book: Theology of the Pain of God: The First Original Theology from Japan by Kazoh Kitamori 1958. (Amazon link)

Book: Theology of the Pain of God: The First Original Theology from Japan by Kazoh Kitamori 1958. (Amazon link)

Publisher: Wipf and Stock Publishers

This was a fascinating book! Kazoh Kitamori writes of the pain of God based on Jeremiah 31:20, in which, from the Japanese Literal version, God declares, “My heart is pained.” Predating by many years Jürgen Moltmann’s Crucified God, Kitamori writes of the pain of God “outside the gate” (Heb. 13:12). This pain is primarily one not of substance, but of relation, for Kitamori. It is because God is love that God is pained, because God loves the object of His wrath: human beings—this is the pain of God. God embraces those who cannot be embraced, God “enfolds our broken reality”. This is a beautiful work, well worth careful attention, especially for fans of Moltmann’s theology.

Given the time it was written (1946 in Japan, and later in English in 1965), it is a truly remarkable project. Although I do think it lacks some of the more precise elements in Moltmann’s theology—and for that reason I regrettably admit that it’s been superseded by Moltmann’s work—it remains a fascinating work well worth reading. It is, however, very difficult to compare the two. The Crucified God was first published in 1972, twenty-six years after Kitamori’s Theology of the Pain of God. But in this review, given my enjoyment of Moltmann’s theology, as one of my three favorite theologians (alongside Torrance and Barth), I will focus on similarities I enjoyed alongside differences I had reservations about. Enjoy!

Notable Quotes

Some notable quotes that I loved from this book.

“The heart of the gospel was revealed to me as the ‘pain of God.'” (19)

“God in pain is the God who resolves our human pain by his own. Jesus Christ is the Lord who heals our human wounds by his own (1 Peter 2:24).” (20)

“Salvation is the message that our God enfolds our broken reality. A God who embraces us completely—this is God our Savior. Is there a more astonishing miracle in the world than that God embraces our broken reality? …Accordingly the pain of God which resolves our pain is ‘love’ rooted in his pain.” (20-1)

“Luther calls the death of Christ ‘death against death’; I call the pain of God ‘pain against pain’.” (21)

“The ‘pain’ of God reflects his will to love the object of his wrath. … Luther sees ‘God fighting with God’ at Golgotha. God who must sentence sinners to death fought with God who wishes to love them. The fact that this fighting God is not two different gods but the same God cause his pain.” (21)

“Every form of docetism results in a denial of the pain of God. … Only the pain of God can deny fundamentally every sort of docetism. It is now clear that the concept of the pain of God upholds the significance originally attached to the historical Jesus.” (35)

[Docetism is the heretical denial of Jesus’ earthly, human body.]

“The message ‘the Son of God has died’ is indeed most astonishing. ‘It is impossible for us to understand the logic of Paul completely unless the death of Christ means the death of God himself.’ God has died! If this does not startle us, what will? The church must keep this astonishment alive. The church ceases to exist when she loses this astonishment.” (44)

“The most urgent business before the church and theology today is the recovery of wonder, the pronouncement of the gospel afresh in order to make this wonder vivid again.” (44)

[This perhaps may be my favorite quote in the book!]

“We conclude from this that God’s pain was fitting for him. ‘To be fitting’ means to be necessary to his essence. The pain of God is part of his essence! This is really the wonder. God’s essence corresponds to his eternity. The bible reveals that the pain of God belongs to his eternal being.” (45)

“The cross is in no sense an external act of God, but an act within himself.” (45)

“The essence of God can be comprehended only from the ‘word of the cross.'” (47)

“If we center our pain in the pain of God, until it is purified by his, our pain is saved from sinfulness for the first time.” (54)

[Here’s where I start disagreeing with Kitamori.]

“Isaiah 63:9 says that God suffers with suffering mankind, but this is quite different from the gospel of the cross—God’s pain in loving sinful men. Jeremiah 31:20, however, literally agrees with the truth of the cross. No more appropriate words can be found to reveal the truth of the cross.” (59)

[This is perhaps the clearest statement of difference between Kitamori and Moltmann. For Moltmann God’s suffering in Jesus Christ is His solidarity with a suffering humanity. For Kitamori, God is in pain as the God who loves the objects of His wrath.]

“We cannot know what the pain of God is; we can know it only through our own pain. Our pain must witness to the pain of God by becoming the symbol of the pain of God.” (60)

[Kitamori calls this the analogy of pain (analogia doloris).]

Conclusions

Following these quotes Kitamori develops upon this symbol of pain into a mysticism of pain. It’s at these two points that I find the most difficulty with Kitamori’s premise. I enjoyed greatly the first half of the book, as you can tell with the quotes I present here. This is a brilliant book but I have my concerns with the later half of it.

Kitamori uses the pain of human beings as the analogy of the pain of God: we know God’s pain through our own pain. This stinks of natural theology, sadly. Moltmann is far more helpful in pointing us, above all else, to the suffering of Jesus Christ on the cross. This and this alone is the right place to begin with a theology of God’s suffering. But sadly, Kitamori reaches this same conclusion of God’s pain, but wrongly by emphasizing our pain as the place of undressing God’s pain. Moltmann is right in saying that it is God’s suffering in Jesus Christ, not our pain, that is the basis for understanding God in our suffering.

In turn Kitamori spirals even further into problematic theology when he deals with the mysticism of pain. Kitamori begins to glorify pain, which is something we must reject. He seems to say that when we are in pain, when we suffer, we are closest to God, that pain is our entrance into life with God.

One of the principle problems this is rooted in is that Kitamori seems to place the pain of God above the love of God. God loves because God is pained, not the reverse. Accordingly, for Kitamori, there is no God higher than the God of pain, and thus pain is never truly overcome. We do not overcome pain, we join God in His pain. This, again, is something we cannot follow.

When Kitamori talks about the mysticism of pain, he writes in such a way that glorifies pain as the highest good. This culminates in a rather chilling statement towards the end of the book. Kitamori writes, “To hate oneself through the medium of the wrath of God is to live in the pain of God. This is unreachable grace. For the wrath of God is used as the medium of the pain of God for our salvation, although it basically means our destruction.” (83) We are encouraged, in the mysticism of pain, to hate ourselves in giving ourselves over to God’s wrath—which seems for Kitamori to be an absolute wrath of arbitrary hatred—to justify our pain in God’s pain.

From this Kitamori moves from the mysticism of pain to the ethics of pain, and finally into the transcendence of God’s pain in the hidden God. As I said, this later half of the book I have great difficulty following, as I have made clear. Moltmann is far more helpful in understanding God’s suffering with us.

However, this does not mean that Kitamori’s work is to be wholly rejected. I tremendously enjoyed this book, and find it helpful and insightful, especially given it’s publication date. Given the history it is written into (just after World War II) it is remarkable. As the quotes above show, there is much to appreciate here, and for that reason I can recommend this book to anyone interested in a theology which takes seriously God’s suffering in Jesus Christ. However, I do so with clear reservation.

Overall I would give this book four out of five stars. I can’t bring myself to give it any less, because I truly enjoyed it, yet I cannot rightly give it any more. Generally speaking, here is a fascinating book well worth the time!

I’d like to thank Wipf and Stock publishers for the review copy of this book. I was given it with no promise of a positive review, and have fairly and honestly read and reviewed it here.

You can buy Theology of the Pain of God here.

Like this article? Share it!

August 31, 2016

#KBRomans – Quotes from Reading Barth’s Romans

A few weeks ago I read Karl Barth’s classic The Epistle to the Romans and posted quotes to my Twitter and Facebook pages. I posted these with the hashtag #KBRomans. I had a blast doing it and seeing the responses from everyone online. Generally speaking I really enjoyed this book, although, as even Barth writes in the introduction, there are things I think were over emphasized. But it is a product of its time, and an very important one at that.

A few weeks ago I read Karl Barth’s classic The Epistle to the Romans and posted quotes to my Twitter and Facebook pages. I posted these with the hashtag #KBRomans. I had a blast doing it and seeing the responses from everyone online. Generally speaking I really enjoyed this book, although, as even Barth writes in the introduction, there are things I think were over emphasized. But it is a product of its time, and an very important one at that.

This book is one of Barth’s most well-known, though as much as I have read Barth and written much about him here, I had not read it up until now. The book launched Barth’s theological career, and is without a doubt a fascinating book. It’s one that Barth himself later moved beyond and would come to disagree with much of it, but I enjoyed it. Here I wanted to compile some of my favorites, as well as some comments on them. Enjoy!

#KBRomans Quotes

“If I have a system, it is limited to a recognition of what Kierkegaard called the ‘infinite qualitative distinction’ between time and eternity…” (p 10)

Here’s a summary of Barth’s primary theme in Romans. Kierkegaard finds his way into the book often, and this idea of the distinction between us and God, of time and eternity, is prevalent for the entire commentary.

“And so, when we set God upon the throne of the world, we mean by God ourselves.” (p 44)

Here Barth is crushing natural theology with a devastating blow. When we posit God as the “highest good” of our world, as the “ultimate concern” of our humanity, we do not have the God and Father of Jesus Christ—we have ourselves situated on the throne. When we “speak of God by speaking of man with a loud voice” (Barth) we practice idolatry. We set ourselves in the place of God when God is enthroned in our world. God must be seen above our world, transcendent even in His imminence.

“‘Jesus Christ our Lord.’ This is the Gospel and the meaning of history.” (p 29)

“Only when grace is recognized to be incomprehensible is it grace.” (p 31)

Barth has several “grace is…” “faith is…” statements in Romans, but this one is just brilliant. We have a human tendency to make grace natural, but Barth reminds us that grace is always incomprehensible because it is God’s grace. Bonhoeffer called the kind of grace we give ourselves “cheap grace”. But I don’t want the kind of grace I can give myself. We can’t live by human grace. Only by the grace of God, which is mystery, miracle, and incomprehensible.

“Grace is the gift of Christ, who exposes the gulf which separates God and man, and, by exposing it, bridges it.” (p 31)

Another great “grace is…” remark. Barth has often said that grace is never without judgement, that judgement is never without grace. When God acts graciously towards us in Jesus Christ to reconcile us to Himself He at once exposes our sinful condition, He judges it, but only in the act of reconciliation. This is why Barth later develops a revolutionary doctrine of sin in the light of Jesus Christ.

“The Gospel is not a truth among other truths. Rather, it sets a question-mark against all truths. […] Anxiety concerning the victory of the Gospel—that is, Christian Apologetics—is meaningless because the Gospel is the victory by which the world is overcome.” (p 35)

This is one of the most fascinating remarks in the book. Barth rejects apologetics as an attempt to remove the impossibility of the gospel, to make grace natural. Why do we believe? We do not know, only that because we believe we believe by pure miracle, i.e., by grace.

“[The Gospel] is the signal, the fire-alarm of a coming, new world.” (p 38)

“Faith is awe in the presence of the divine incognito…” (p 39)

“Our relation to God is ungodly. We suppose that we know what we are saying when we say ‘God’.”(p 44)

I like this quote. It’s another crushing attack against natural theology. If we take seriously this qualitative distinction between God and man, then our relationship with God can only be ungodly, or in Paul’s terms “unrighteous”. We do not know what “God” is. Only as God reveals Himself to us and sets us right (revelation and reconciliation) can we know who God is.

“The enterprise of setting up the ‘No-God’ [of natural theology] is avenged by its success.” (p 51)

Natural theology is avenged by its success. Those who wish to posit a God in the image of mankind suffer in their success: they are given over to a God who looks like they do. But I for one do not want a God who looks like me. Give me the God and Father of Jesus Christ or no God at all.

“God does not live by the idea of justice with which we provide Him. He is His own justice.” (p 76)

“[God] declares that He has espoused our cause, and that we belong to Him.” (p 101)

One of the most powerful things I learned from Barth in CD IV/1 is that in Jesus Christ God has taken up our cause as His own. This is how fully we belong to Him.

“[God] is the death of our death and the non-existence of our non-existence. He makes alive and calls all things into being.”

Another great “grace is…” quote. From page 207.

“[Adam] exists only when he is dissolved, and he is affirmed only when in Christ he is brought to nought.” (p 171)

For Barth, Adam’s fall takes place in Christ’s world, Christ’s redemption does not take place in Adam’s world. See this article for more.

“Faith is the possibility which belongs to men in God, in God Himself and only in God when all human possibilities have been exhausted.” (p 202)

“Men [and women] can apprehend their unredeemed condition only because they stand already within the realm of redemption.”

“[Men and women] know themselves to be sinners only because they are already righteous [in Christ].”

“God has justified Himself in our presence and us in His presence.” (p 150)

Barth writes in CD IV/1 that the first act of justification is God’s justification of Himself in the raising of Jesus Christ. Here he seems to echo a similar point.

“I am transformed, renewed, purified, made a participator of the divine nature, of the divine life, in Him. This is adoption.”

“If Christianity be not altogether thoroughgoing eschatology, there remains in it no relationship whatever with Christ.” (p 314)

Barth sounding a bit Moltmannian with this one! It’s a shame Barth never completed his final volume on eschatology (the planned CD V).

“Faith is miracle. Otherwise it is not faith.” (p 366)

“To know God means to stand in awe of Him and to be still in the presence of Him that dwells in light unapproachable.” (p 463)

Conclusions

And there you have it. These were just some of my favorites from Barth’s Romans, quotes that I tweeted during my #KBRomans tweeting season! Feel free to check out the rest of the quotes at the hashtag #KBRomans on Facebook or Twitter.

Which book should I do next? I’ve thought of either Barth’s CD II/1 or possibly TF Torrance’s Trinitarian Faith as two options for the next Twitter/Facebook quote session! Which do you think I should do? Let me know in a comment below! I hope you enjoyed #KBRomans.

August 12, 2016

God Rejects TO Elect (Jacob, Esau, Romans 9, and Karl Barth)

“Jacob I loved, but Esau I hated.” Paul writes this in Romans 9:13, and it has since been the cause for endless debate, especially in the protestant church. The most well known interpretation of this verse is the calvinist’s doctrine of “double-predestination”, in which God chose Jacob and rejected Esau. We therefore have these two categories: the elect and the reprobate, God’s chosen and God’s rejected individuals. The elect are those chosen by God from before all eternity to be His people, and the reprobate are chosen by God not to be His people.

“Jacob I loved, but Esau I hated.” Paul writes this in Romans 9:13, and it has since been the cause for endless debate, especially in the protestant church. The most well known interpretation of this verse is the calvinist’s doctrine of “double-predestination”, in which God chose Jacob and rejected Esau. We therefore have these two categories: the elect and the reprobate, God’s chosen and God’s rejected individuals. The elect are those chosen by God from before all eternity to be His people, and the reprobate are chosen by God not to be His people.

Karl Barth, a reformed theologian often considered the most influential of the 20th century, has a different opinion about this. When I first read Barth it was because I had heard the rumor that he had developed a theology which explained election in a satisfactory way which retains at once God’s will to love all people and be for all people, and His sovereign grace. With this revision to election Barth offers an alternative to classic arminianism and calvinism alike.

Barth’s most magnificent treatment of election is in his famous Church Dogmatics volume II/2. This is where Barth takes a “christocentric” approach to the doctrine of election, which says that Jesus Christ is at once the electing God and the elected man. God says “yes” to Himself in Jesus Christ, and in Him God says “yes” to the human race. This is God’s self-determination to be, from before all time, God-for-us.

I’ve written about this doctrine elsewhere on my website 1, but today I want to share Barth’s comments on this verse which come from his famous The Epistle to the Romans. [LINK] Here Barth shows an early doctrine of election which he later forms more fully in CD II/2, but it is nonetheless a remarkable understanding of election. Barth writes:

“Jacob I loved, but Esau I hated. This—we again repeat it—is descriptive of the behaviour of God and of the quality of His action. Only as free, regal, sovereign, unbounded and incomprehensible, can we comprehend God and do Him honour. […] He makes Himself known in the parable and riddle of the beloved Jacob and the hated Esau, that is to say, in the secret of eternal, twofold predestination. Now, this secret concerns not this or that man, but all men. By it men are not divided, but united. In its presence they all stand on one line—for Jacob is always Esau also, and in the eternal ‘moment’ of revelation Esau is also Jacob. When the Reformers applied the doctrine of election and rejection (predestination) to the psychological unity of this or that individual, and then they referred quantitatively to the ‘elect’ and the ‘damned’, they were, as we can now see, speaking mythologically.“ 2

And furthermore, Barth writes commenting on verse 14:

“Such a separation of men can only be allowed to appear, if it be at once broken down, and if by its immediate disappearance God be manifested as He is. For God is the God of Esau, because He is the God of Jacob. He is the creator of tribulation, because He is the bringer of help. He rejects, in order that He may elect.“ 3

God rejects only because God elects; God rejects to elect. This is how Barth understands Paul’s usage of the story of Esau and Jacob. Barth rightly notes the mythological nature of predestination in the reformed theology, which focuses on the election or rejection of individuals. Barth will later understand this to be the concrete election of Jesus Christ, but even here he understands that the reformers were practicing mythological speculation when they formed their doctrine of double predestination.

Romans 11:32 says that “For God has imprisoned all in disobedience so that he may be merciful to all.” This seems to be what Barth has in mind here with rejection being for the sake of election. And in this sense we might say that rejection is temporal while election is eternal. God acts for the sake of election, and never in spite of election. Thus, the individuals God has given over to disobedience, to rejection, are given over for the sake of salvation, not for the sake of arbitrary or outright rejection.

Barth also seems to have in mind here the fact that God is the God of Jacob and Esau in the same way that God is the God of the old and the new creation. Barth seems to link, in the back of his thought, the sinner and the saint, the old and the new creation. Barth notes that this election and rejection is not an equilibrium, that is, it is not equally balanced. Instead, this is “the eternal victory of election over rejection.” 4 This victory of election over rejection is the victory of the new creation over the old, the resurrection of Jesus Christ in triumph over His death on the cross. This is how Barth speaks of human beings as both Jacob and Esau, because we are those who are “on the way” from death to life, from the old to the new creation in Him.

This is a fascinating look at Barth’s doctrine of election, though in an early form. Even here Barth brilliantly revises the doctrine of election, placing election properly (and rightly) at the center as God’s ultimate will for human beings. God is not the God both for and against individuals, God is the God who is for us, for all humanity!

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

See: What is Election? (A Summary) and 8 Incredible Karl Barth Quotes. ↩The Epistle to the Romans, 347; emphasis mine. ↩Ibid. 351; emphasis mine. ↩Ibid. 347 ↩August 11, 2016

God’s Being in Suffering (Barth and Jüngel)

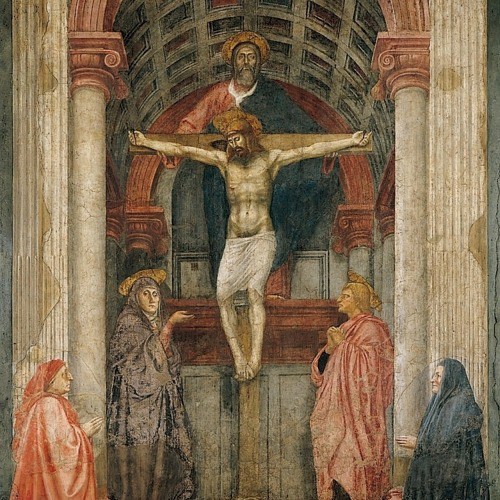

Masaccio’s Holy Trinity

When Jesus Christ suffered and died on the cross, where was the Father and the Spirit? In what way was the being of God as Father and Spirit involved in the suffering and death of the Son? Was Jesus alone in His suffering, was He in isolation from the Father and the Spirit, somehow separated from His own Trinitarian being, or is there some way in which the Father and the Spirit shared in the sufferings of Jesus Christ? Does God suffer?

Patripassianism is the heretical belief that the Father died on the cross, that the Trinity is not three distinct persons (Father, Son, and Spirit) but one person who appears to us in three different ways (called modalism). This is not what we are talking about, modalism is a false understanding of the Trinity. But is there perhaps a more properly Trinitarian way of understanding the cross? A Trinitarian understanding of the crucifixion which does not fall into modalism, which does not exclude the Father or Spirit in the suffering of Jesus Christ, yet keeps their sufferings distinct?

Karl Barth offers a brilliant yet subtle modification to patripassianism, and Eberhard Jüngel notes this in his book on Barth’s doctrine of the trinity, God’s Being Is in Becoming. [LINK] Barth rightly rejects modalism, but at the same time he does not fall into the error of wholly removing the Father or the Spirit from the event of Christ’s suffering and death. Instead, the Father and the Spirit are involved in Christ’s death, they are affected by His suffering and by His death even if they are distinctly set apart from it.

The painting aptly entitled “Holy Trinity” by Masaccio portrays this beautifully (see above), showing the Son suffering on a cross held up by the Father with the Spirit as a dove between them. So exactly how does Barth modify patripassianism without falling into modalism? Jüngel writes:

“And so God as God has declared himself identical with the crucified Jesus. Therefore one must not exclude from this suffering the Father who gave his Son over to suffer death. ‘It is not at all the case that God has no part in the suffering of Jesus Christ even in His mode of being as the Father.’ [Barth, CD IV/2, 357] … Thus the Father, too, participates with the Son in the passion, and the divine unity of God’s modes of being prove itself in the suffering of Jesus Christ. God’s being is a being in the act of suffering. … In giving himself away God does not give himself up. But he gives himself away because he will not give up humanity.” 1

And furthermore, Jüngel writes:

“No concept of God arrived at independent of the reality of Jesus Christ may decide what is possible and impossible for God.” 2

We cannot say that on the cross God remained unaffected by the sufferings of Jesus Christ, we cannot say it is impossible for God to suffer when by identifying Himself with Jesus Christ God has shown this to be possible. No independent thought about what God can or cannot be or do apart from the revelation of God in Jesus Christ can tell us what God is like, whether or not God suffers or is above suffering.

The Father did not die on the cross, but this does not mean we can say that the Father remains unaffected by the death of the Son. We have to say, since God has identified Himself with Jesus Christ, that God’s being is being in the act of suffering. In short, that God suffers.

Jüngel followed Barth’s insight here and developed it significantly in what’s often considered his masterpiece: God as the Mystery of the World. [LINK] With Jürgen Moltmann, Jüngel argues that God suffers in the death of Jesus Christ, that “God’s being is a being in the act of suffering.” Thus, both reject the common notion of God’s inability to suffer (impassibility). This commonly held notion that God is above suffering, that God is not a God who is affected by our death and corruption, is shattered in the light of Jesus Christ. Those who take Christ’s death seriously as God’s suffering in our humanity inevitably make this conclusion: God, in fact, can and does suffer with us in Jesus Christ.

I’ve often said here how much I enjoy the theology of Jürgen Moltmann, and this is why: Moltmann’s insistence upon God’s suffering is brilliant. But here we see this insight in Barth’s thought already before Moltmann or Jüngel made it explicit in their work. Learning this was new for me, I had not seen this from Barth’s theology until I read Jüngel’s work on it. So I’m planning to read through CD IV/2 with this in mind, as well as to read Jüngel’s God as the Mystery of the World to explore more this insight—one which I often believed to be exclusively Moltmannian, but now has appeared to be more diverse.

Does God suffer? According to Moltmann, Jüngel, and even Barth: Yes!

For more on this see similar articles I’ve written: The Weakness of God and T. F. Torrance on the Passible Impassibility of God. Also see my book on Moltmann, which is free for those in my Readers Group: Where Was God?

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

God’s Being Is in Becoming, page 102 ↩Ibid. 99 ↩July 31, 2016

Grace as Solidarity (Gollwitzer)

Here’s a great quote on grace as solidarity by Helmut Gollwitzer, one of Barth’s students in Basel, and it comes from a sermon collected in the book The Way to Life. Enjoy!

“The beautiful word ‘grace’, which originally means ‘to turn oneself to someone to help’, even this beautiful word is unfortunately so hackneyed, that some years ago a Jewish scholar proposed to clarify it and make it come alive for us by using the modern word ‘solidarity’. The man who is solidary with us, who is consistently and wholly on our side, shares everything with us, does not wish to be better off than us, puts at stake for us everything that he has and can, fights for us, and will see it that we are served. …’God is solidary with us’… We are surrounded, carried, ruled and expected by an eternal Solidarity that stands on our side, suffers with us, fights for us, sacrifices itself of us, and wins the future for us. That is our reality, this is the source of our life. This Solidarity gives us guidance for our life, and at the same time promises to stand in for us when, through following its guidance, as is to be expected, we meet hostility and the gravest affliction. This is the confidence of those who hear and receive this Solidarity. … And when we treat in an opposite manner the man who at our side is downtrodden and oppressed and hungry, and ourselves tread others down and oppress them, then we are unsolidary with the God who is solidary with this fellow-man, and whose solidarity is the source of our own life.

“To believe means: to hear this Solidarity speaking with us, and to speak with it, and to rely more on it than on all other solidarities, with a reason for confidence which remains when all other reasons for confidence collapse. … And to believe means to be solidary with those with whom God is solidary, a messenger of the solidarity of God in relation to the man next to us, because he is not solidary with us without being solidary with the man next to us. Solidarity is freedom for the other man, as God is free for us.“ 1

God in Christ became our brother, took up our condition as His own, took up solidarity with us in our humanity. Gollwitzer here beautifully brings out the twofold nature of God’s solidarity with us. It is a solidarity of God with us in our difficulties, in our human condition, but it is at once our solidarity with God in another, our freedom to be for another, for the downtrodden and oppressed, to see God in the face of the broken. May we all learn to be more in solidarity with our neighbor as we follow the lead of Jesus Christ who has taken up solidarity with us!

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Gollwitzer, The Way to Life, p 16-7; bold mine; italics in the original. ↩