Stephen D. Morrison's Blog, page 10

July 27, 2016

A Barthian Critique of Paul Tillich’s Systematic Theology

Last week I posted some of Karl Barth’s comments on Paul Tillich’s Systematic Theology. [LINK] Today I finished reading the excellent book this comes from: The Systematic Theology of Paul Tillich by Alexander J. McKelway. [LINK] This book is a dissertation presented to and written under the guidance of Karl Barth. It is thus a truly “Barthian” analysis and critique of Tillich’s theology. I really enjoyed it! The book put words to some of the reservations I’ve felt whenever reading Tillich’s theology, but it also helped me understand Tillich better and appreciate him more, if ultimately I still find him unhelpful as a theologian.

Last week I posted some of Karl Barth’s comments on Paul Tillich’s Systematic Theology. [LINK] Today I finished reading the excellent book this comes from: The Systematic Theology of Paul Tillich by Alexander J. McKelway. [LINK] This book is a dissertation presented to and written under the guidance of Karl Barth. It is thus a truly “Barthian” analysis and critique of Tillich’s theology. I really enjoyed it! The book put words to some of the reservations I’ve felt whenever reading Tillich’s theology, but it also helped me understand Tillich better and appreciate him more, if ultimately I still find him unhelpful as a theologian.

Today I want to briefly outline some of Tillich’s Systematic Theology (hereafter abbreviated “ST“), and most of all work through some of McKelway’s central critiques of the scope and method of his project.

Ultimately, this book does not affirm Tillich, nor does it endorse him. It sees the positive aspects to his theology, and therefore does not outright reject him. Tillich’s project is questioned with the seriousness it deserves. And ultimately, I must agree with McKelway’s conclusions. Tillich’s theology is deeply flawed, theologically unhelpful, and ultimately it fails to succeed in proclaiming the revelation of God in Jesus Christ.

First, we’ll look at an outline of Tillich’s ST, and then some of the essential criticisms McKelway presents against it. I most of all recommend you read this book (click the link above to buy it), because, as Barth warned, we should avoid any “immature or superficial critique of Tillich”, and here is a very helpful analysis of his thought. If you’re at all interested in Tillich, I highly recommend it. McKelway clarifies Tillich’s somewhat difficult language, making it easier to understand him on his own terms before we bring any criticisms against his project.

Five Parts to Tillich’s ST

Tillich’s ST is broken up into three volumes, with five parts. These are formed by Tillich’s fundamental method: correlation. McKelway offers a helpful summary of this method, he writes,

“…the theology of Paul Tillich begins with man. For it is man who, asking the question of his own being, discovers in God the ground of being; it is man’s situation in existence which causes him to ask after the New Being in Jesus as the Christ. It is with man that Tillich begins, and it is this point of view, this interest, which controls his definition of the nature of theology and its method, and which regulates the form, if not the content, of his interpretation of the Christian message.” 1

Tillich follows five questions of man and his condition which God answers throughout the entire volume. Thus, Tillich divides his ST into five parts, always first dealing with man’s condition and his question, then God’s answer and it’s corresponding theological doctrine. These five correlations are:

I – Reason and Revelation (the doctrine of revelation)

II – Being and God (the doctrine of God)

III – Existence and the Christ (the doctrine of Christ and of the atonement)

IV – Life and the Spirit (the doctrine of the Spirit and of the church)

V – History and the Kingdom of God (Eschatology)

This is the outworking of Tillich’s method of correlation. The existence of man “correlates” with the answer given by theology, but the question also determines the form of that answer (an important point we’ll return to!).

Here we will not go into the details of each of these sections, though it helps to know this background information. The main issue we’ll present, however, is a critique against Tillich’s method which begins with man and ends with God, in which man determines the form and even content of God’s word to man! We’ll see why and what this means for Tillich’s theology in what follows.

Barthian Critiques of Tillich’s ST

McKelway notes that the fatal flaw in Tillich’s method of correlation is that,

“Basic to the method of correlation is the expectation and demand that the revelatory answer to man’s question takes the form of those question, fulfill their demands, and answer the questions in the terms in which they are asked.“ 2

Accordingly, the answers that theology gives to the questions of man’s condition are determined by that condition. This is, for Tillich, inherent to his rejection of Kerygmatic methods of dogmatics which “error [by] throw[ing] answers, like stones, at the heads of those who have not yet asked the questions.” Therefore the answers cannot be likes stones thrown needlessly at those who have not asked the questions they answer, but the Christian message must have the character of being familiar to the questioner. Therefore, the answers theology provides must be determined questions in the condition of man, because, for Tillich, they must be intelligible to the condition of man (and not unintelligible stones thrown at us from above).

In the light of this, it is already decided that the theology Tillich provides is not of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ, but of man’s questions first as it is in relation to God’s answers in Jesus Christ. God’s answering is therefore determined by man’s questioning!

The flaw in this is quite obvious. The central problem with Tillich’s theology is the lack of consistent emphasis on the person of Jesus Christ as God’s self-revelation. McKelway writes,

“The central and all-embracing problem of the place and character of Jesus Christ in Paul Tillich’s Systematic Theology is the reason we are not able, finally, to accept either his view of theology as apologetic or the method of correlation. For the apologetic requirement for an understanding of the human situation cannot be fulfilled except in the light of the final and decisive word spoken about man and to man in Jesus Christ; nor can the revelation of God be seen apart from the one event in which he did reveal Himself, Jesus Christ. These assertions must be the standard against which every theology is judged.” 3

And thus at the critical point of Tillich’s theology, McKelway concludes:

“This problem and danger, to put the matter simply, is the lack of a consistent focus on the revelation of God in Jesus Christ. …We cannot speak of God apart from what he has revealed himself to be in Jesus Christ.” 4

The most dangerous aspect then, about Tillich’s ST, comes out best in his Christology. Tillich, “seriously consider[s] the meaning of the Christian message apart from Jesus. 5 He therefore embraces two fatal errors which undermine the whole task of theology in such a way that his method must ultimately be rejected.

The first, and most essential, is that for Tillich, there is a God hidden behind the back of Jesus Christ. Tillich posits an explicit doctrine of God’s hiddenness which stands over and against Jesus Christ. Tillich goes so far as to say that “Jesus of Nazareth is sacrificed to Jesus as the Christ.” (ST I, 135) And since Tillich maintains that the nature of revelation is unchanged in this sacrifice of Jesus to the Christ, Tillich asserts that God is fundamentally unknown, that there is a deep abyss hidden behind God’s self-revelation in Jesus Christ. Jesus of Nazareth is an unreliable source of knowledge for Jesus the Christ, and thus Tillich presents us with a God hidden behind Jesus Christ.

This is absolutely fatal in our critique of Tillich. That there is a God behind the back of Jesus Christ means, as McKelway rightly notes, that, “Such a view of revelation can only leave man in the most radical doubt as to whether he will stand on that ground or fall into that abyss.” 6

This also means that Tillich cannot escape from our second grievance against his theology: that is, he ultimately falls into the trap of natural theology, of applying finite categories to God. Tillich explicitly denies natural theology, but in affirming analogia entis and in the light of his method of correlation we can make no other conclusion. He fundamentally allows and insists that man should define God, that man’s questions determine God’s answers. It is hard to argue that this is not a kind of natural theology, and it’s quite puzzling to me that Tillich thinks he is not teaching a natural theology. But McKelway notes of Tillich’s method of correlation,

“The greatest problem which this writer sees in Tillich’s ontological analysis of being is one which we have already noted in the last two chapters. It is the question of a natural relation between God and man which causes an awareness of God in man and which allows man to apply finite categories to God. This is the old question of natural theology.“ 7

The result is a doctrine of God which has nothing to do with either God’s acts in Jesus Christ, or the accounts of God’s acts in scripture. McKelway again notes,

“The thing that is most striking about Tillich’s doctrine of God is that nowhere are his assertions said to be based upon God’s acts as they are revealed in Christ, still less are they based on any exegesis of the record of those acts in Holy Scripture. … In this situation is there not bound to arise in the reader’s mind a suspicion that the content of Tillich’s doctrine of God is deduced from his analysis of being rather than received from revelation itself?” 8

Because Tillich ultimately rejects the self-disclosure of God in Jesus Christ (by sacrificing Jesus to the Christ), he is forced to posit a God hidden behind the back of Jesus Christ; and furthermore, he in turn errors in attempting to know this “hidden” God through natural theology, by looking to man and his questions concerning his being.

Conclusions

These two critiques force us to come to the unfortunate conclusion that ultimately Tillich fails in his method and in his task for an apologetical theology. We cannot outright reject Tillich, but we must here deem him ultimately unhelpful. As McKelway rightly notes, there are some positive elements to Tillich’s theology which we can certainly learn from. In fact, he says that “No one who reads Tillich can fail to learn from him.” 9 There is no doubt, then, that Paul Tillich is brilliant. But is he helpful? Ultimately, no.

His failure on these two key points leads to further doctrinal heresies including an adoptionist Christology, a denial of the resurrection, and a very problematic doctrine of the Trinity. For these reasons we must be skeptical of Tillich, beyond the two already fatal flaws in his thought: that of a God hidden behind the back of Jesus Christ, and of natural theology.

Ultimately, as we’ve noted with McKelway, Paul Tillich’s greatest failure is his lack of a consistent focus on the revelation of God found in Jesus Christ.

For this reason my conclusion is that Tillich is ultimately unhelpful in the task of theology. This does not mean that he is to be completely rejected, as some elements of his anthropology and ontology are (at times) insightful, but certainly his theology is altogether unhelpful as a theology.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

McKelway, The Systematic Theology of Paul Tillich, 38 ↩Ibid, 93 ↩Ibid, 261 ↩Ibid, 177 ↩Ibid, 25; emphasis mine ↩Ibid, 100 ↩Ibid, 139 ↩Ibid, 141 ↩Ibid, 269 ↩July 22, 2016

Karl Barth on Tillich’s Systematic Theology

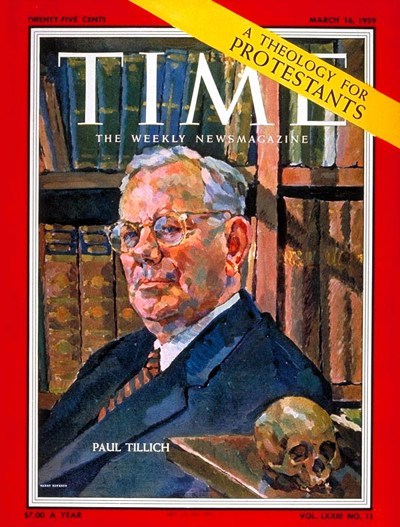

Paul Tillich on the cover of Time Magazine; March 16th, 1959

Paul Tillich is a theologian of interest for me, despite my partiality to Karl Barth. 1 Barth, Bultmann, and Tillich are often considered the three most influential names in 20th century theology (though I’d like to add TF Torrance to that list!), and so Tillich is certainly an important thinker worth reading and engaging with thoughtfully, if also critically.

Tillich interests me because I find his task commendable: to make theology, and God, relevant for the modern world. Tillich famously has said, “I hope for the day when everyone can speak again of God without embarrassment.” (Though I find his method in achieving this task less than commendable! Barth succeeds far more, in my opinion…) But I am also interested in Tillich because of his influence on modern theology. Tillich was an existentialist theologian whose insights have undoubtably helped many find the “courage to be”. But in a negative way many post-modern theologians have also draw from Tillich’s thought, which at times borders on atheism. 2

I’ve read several of Tillich’s major books so far, including some of his sermons (The New Being), his famous Courage to Be, and his Dynamics of Faith—I enjoyed The Courage to Be the most from these. But I have yet to dive into his three volume Systematic Theology. I am holding any definitive opinions about his theology until I’ve read this, as I’d recommend anyone do with any prominent thinker: be slow to make judgements and take up the important but slow task of reading and engaging with their work!

As a part of my interest in Tillich, I do plan to read his Systematic Theology, but first I am reading an analysis by one of Karl Barth’s students, Alexander J. McKelway; a doctoral dissertation under Barth’s guidance on his theology. His book The Systematic Theology of Paul Tillich looks very promising, but so far (I only began the book today) it has been particularly interesting to read Barth’s “Introductory Report”!

In this report Barth gives his own brief thoughts on Tillich’s theology, and asks some insightful questions of his task which show quite well the differences between these two theological giants. So without any further introduction, here are some of Barth’s comments on Paul Tillich’s Systematic Theology.

Karl Barth on Paul Tillich’s Systematic Theology

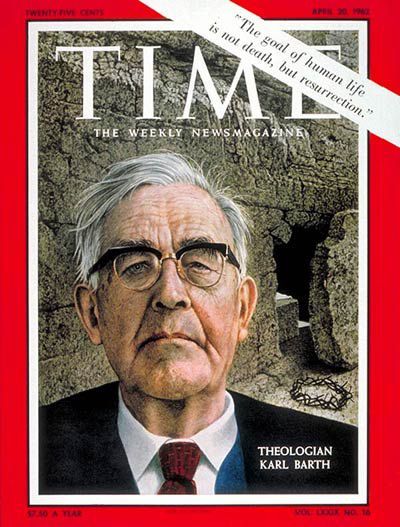

Karl Barth on the cover of Time Magazine; April 20th, 1962

First Barth writes of the importance of engaging with a theologian thoughtfully, of not writing them off without ample and careful study.

“It was my great concern from the very beginning to restrain the students [in my classroom] from any immature or superficial critique of Tillich, and to require of them a careful examination of his underlying intention…” 3

Barth then commends McKelway in his efforts to this regard, that while he “reacts to the thought of Tillich with reservations and objections, he never simply rejects him.” 4 Saying further,

“Indeed, often enough [McKelway] expresses his appreciation for Tillich’s execution as such, for the breadth of his knowledge and interests, for the unfailing consistency of his thought, and for his great artistry which unfolds on every page. Tillich is not affirmed in this book, to be sure, but neither is he placed in some shadow; rather, he is brought to light as one who is in his own way a great theologian.“ 5

What an incredible statement coming from Barth! These two men could not be any further apart in their theology’s, but here Barth shows how respectful dialogue can take place between theologians, even amongst those who so passionately disagreed with each other.

I’ll be honest, I was shocked when I read this sentence. To hear Barth call Tillich a “great theologian” in his own way will certainly surprise anyone familiar with these two individuals and their work. But Barth does not stay in these positive spirits for long (though this fact does not discredit what he has said already). From here Barth begins to look at the content of Tillich’s Systematic Theology, especially Tillich’s (in)famous method of correlation, asking insightful questions to the validity of such a theology:

“Tillich’s methodology, already revealed in the title and concept of the system, proceeds in such a way that both successively and simultaneously the philosophical concepts of reason, being, existence, life, and history are set in correlation with the theological concepts of revelation, God, Christ, Spirit, and the Kingdom of God.

“The Problematic nature of this undertaking is obvious. Since Tillich’s theological answers are not only taken from the Bible, but with equal emphasis from church history, the history of culture generally, and the history of religion—and above all, since their meaning and placement is dependent upon their relation to philosophical questions—could not these answers be taken as philosophy just as well as (or better than?) they could be taken as theology? Will these theological answer allow themselves to be pressed into this scheme without suffering harm to what in any case is their biblical content? Is man with his philosophical questions, for Tillich, not more than simply the beginning point of the development of this whole method of correlation? Is he not, in that he himself knows which questions to ask, anticipating their correctness, and therefore already in possession of the answers and their consequences? Should not the theological answers be considered as more fundamental than the philosophical questions and as essentially superior to them? If they were so considered, then the question and answer would proceed, not from a philosophically understood subject to a ‘divine’ object, but rather from a theologically understood object (as the true Subject) to the human subject, and thus from Spirit to life, and from the Kingdom of God to history. Such a procedure would not actually destroy the concept of correlation, but would probably apply to is the biblical sense of ‘covenant.’ This application, however, is unknown in Tillich.” 6

The question, “Should not the theological answers be considered as more fundamental than the philosophical questions and as essentially superior to them?”, is perhaps the most critical difference between Karl Barth and Paul Tillich. Barth begins with God and works towards man, Tillich begins with man and his philosophical questions and works towards God. For Barth, this is a complete reversal of the entire task of theology! I found this question to be perhaps the best summary of why Barth takes issue with Tillich and the major differences in their theology; and it is also, in my brief and early understanding of Tillich, why I take preliminary issue with his theology (so far as I’ve read).

But I am excited to pull out the good in Tillich’s work from his Systematic Theology with help from McKelway’s analysis (endorsed by Barth!), though soon after by directly reading his work myself! If you’re are interested in Tillich and how a so-called “Barthian” might respond to his theology, I recommend you pick up this book. Once I’ve finished it I’m planning to write up more thoughts, but for now Barth’s introduction has provided plenty of food for thought!

For anyone interested in how these two men differ, here’s my advice (which someone first suggested to me when I asked about Tillich): in order to best glen the differences between these two men, read first Tillich’s sermon “You are Accepted”, and then immediately read Barth’s “Saved by Grace”. (You can read these online here and here.) Comparing these two sermons is perhaps the best way to see immediately how they differ in the practical act of preaching, because here we have an excellent example of how each of these two theologians understood the gospel.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Their theological projects are in some ways polar opposites! ↩Some have argued that Tillich became an atheist himself, though that’s mostly to misunderstand his theology. See this article. Though he is also known to have rarely attended church or prayed. This fact is something truly difficult for me, personally, to overcome about Tillich. ↩p. 11 ↩Ibid. ↩Ibid. ↩Ibid pp. 12-13 ↩July 13, 2016

God Corresponds to Himself (Jüngel and Barth)

If I ever succeed in writing a book that’s even half as theologically precise as Eberhard Jüngel’s God’s Being Is in Becoming, I will die a happy man. 1 This book is an incredibly dense work of theology. With a precise eye for detail Jüngel interprets Barth’s doctrine of the Trinity in a profound and intricate way, all the while with a concise style any writer would be wise to emulate. Though because it is such a dense book, it is at once an incredibly difficult book. Though this is not exactly due to Jüngel’s style (though that’s probably also the case), but because of the subject at hand: the doctrine of the Trinity. If anywhere in theology there is required careful precision and complexity, it is here.

If I ever succeed in writing a book that’s even half as theologically precise as Eberhard Jüngel’s God’s Being Is in Becoming, I will die a happy man. 1 This book is an incredibly dense work of theology. With a precise eye for detail Jüngel interprets Barth’s doctrine of the Trinity in a profound and intricate way, all the while with a concise style any writer would be wise to emulate. Though because it is such a dense book, it is at once an incredibly difficult book. Though this is not exactly due to Jüngel’s style (though that’s probably also the case), but because of the subject at hand: the doctrine of the Trinity. If anywhere in theology there is required careful precision and complexity, it is here.

I am about two-thirds of the way through the book; so far I’m enjoying it immensely, and I’m looking forward to the final section. When I was reading (slowly) today, as I tried to grasp the concepts Jüngel was trying to bring forth from Barth’s doctrine of the Trinity, one point in particular struck me that I want to briefly quote and discuss here. That is, the notion that, “God corresponds to Himself”.

God Corresponds to Himself

The interesting thing about this phrase isn’t just how profound it is (though it is) and how important it is for understanding the Trinity (which it is), but the fact that for Jüngel, this phrase sums up the entirety of Barth’s project in the Church Dogmatics. He writes that the entire Dogmatics is basically an interpretation of this idea! So it is important to understand what he means by it and how it relates to the Trinity. But first, we’ll quote Jüngel for context:

“…God’s being ad extra [externally, for us] corresponds essentially to His being ad intra [internally, in Himself] in which it has its basis and prototype. God’s self-interpretation (revelation) is interpretation as correspondence. Note: as interpreter of Himself, God corresponds to His own being. But because God as His own interpreter (even in His external works) is Himself, and since in this event as such we are also dealing with the being of God, then the highest and final statement which can be made about the being of God is: God corresponds to Himself.

“Barth’s Dogmatics is in reality basically a thorough exegesis of this statement. Once it is not understood as an attempt to objectify God, but as an attempt to grasp the mystery of God where it is revealed as mystery, then this statement implies a movement which, over and above brilliance and diligence, makes possible a dogmatics of the stature of the Church Dogmatics. The Dogmatics is a brilliant and diligent attempt to reconstruct in thought the movement of the statement ‘God corresponds to Himself.'” 2

What does Jüngel mean by “correspond” here? He further states,

“That God corresponds to Himself is a statement of a relation. The statement means that God’s being is a relationally structured being.” 3

This is, for Jüngel, another way of explaining God’s self-relatedness. This self-relatedness is God’s distinction, the distinction of God in three modes of being.

In other words, here we have the doctrine of the Trinity, not abstractly, but concretely related to the world. This idea that God is the one who corresponds to Himself is another way of saying that God is the one God who reveals Himself in His Self-revelation (Jesus Christ). The fact that God reveals Himself is for Barth the basis for the doctrine of the Trinity. He writes, “One may sum up the meaning of the doctrine of the Trinity briefly and simply by saying that God is the One who reveals Himself.” 4 For Barth, this phrase works out into God’s three modes of being:

“God reveals Himself. He reveals Himself through Himself. He reveals Himself. If we really want to understand revelation in terms of its subject, i.e., God, then the first thing we have to realize is that this subject, God, the Revealer, is identical with His act in revelation and also identical with its effect.” 5

God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit in revelation is God the Revealer, God the revelation, and God the effect of revelation; but since God is this in revelation, God is this in Himself. Therefore, this is the basis for the doctrine of the Trinity. That God reveals Himself through Himself as His own self-interpreter, means that God is the Triune God.

And this is what Jüngel is getting at. That “God corresponds to Himself” is another way of saying that God is who He is in His self-revelation. God’s being in revelation corresponds to His being in Himself. This point dictates the whole of the Church Dogmatics as Barth thinks in Trinitarian and Christocentric terms through the whole of God’s acts in election, creation, reconciliation, and redemption.

Conclusions

This is an incredibly complex subject, but Jüngel is precise in his work. This notion that God corresponds to Himself is important for Barth’s theology, and for Trinitarian theology as a whole. It is fascinating that Jüngel calls this the idea which Barth is working with in his entire Church Dogmatics, but the more I think about it the more I think he is right.

Take, for example, the doctrine of election. For Barth, election is God’s self-determination in Jesus Christ to be God for us; election is Jesus Christ. God says “Yes” to Himself and that “Yes” is echoed in our humanity in Jesus Christ. That God corresponds to Himself here means that God’s act in Jesus Christ for us corresponds to God’s act in Himself. God therefore is the God who from before all time determined to be our God, to be for us in Jesus Christ. The revelation of Jesus Christ as God for us corresponds to the being of God for us, the God who from before all time determined to be our God. This is why, for Barth, election must be Christocentric: Jesus Christ is the object and subject of election, the electing God and the elect human being.

There is much to think through in regards to this idea, as it is a tremendously potent idea, but for now I wanted to show how it relates to Barth’s doctrine of the Trinity, which permeates the whole of his Dogmatics. Jüngel’s book is incredibly dense and full of insights into the being of God. I’m excited to finish reading it, and for a long time after continue thinking through these ideas.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Here’s a LINK if you want to buy the book. ↩God’s Being Is in Becoming, Jüngel p. 36. Brackets and emphasis (bold) mine. ↩Ibid p. 37 ↩CD I/1, 380 ↩CD I/1, 296 ↩July 9, 2016

Double Predestination is Unbiblical (Emil Brunner)

Today I finished reading Emil Brunner’s Dogmatics: Volume I, The Christian Doctrine of God. 1 There are many positive things I could say about the volume, and I did enjoy much of Brunner’s emphasis upon the revelation of God in Jesus Christ (though there were also many things I disliked).

Today I finished reading Emil Brunner’s Dogmatics: Volume I, The Christian Doctrine of God. 1 There are many positive things I could say about the volume, and I did enjoy much of Brunner’s emphasis upon the revelation of God in Jesus Christ (though there were also many things I disliked).

Brunner, with Barth, fiercely rejects natural theology, though, as I mentioned in a previous post, he still retains a “revelation in nature” where Barth does not. And the disagreements do not stop here. Barth and Brunner are similar in their dedication to the word of God in Jesus Christ, but the way they each work out that revelation into theology is very different. Brunner takes issue with Barth on many things, for example Barth’s doctrine of election which Brunner feels is far too close to universalism. 2

But Barth and Brunner’s differences aside, what I found especially interesting in the last section was Brunner’s treatment of election. He rejects Barth’s doctrine of election, but he also rejects Calvin’s double decree. This rejection of double predestination is something I really enjoyed (probably the highlight of the book for me), even if I think his rejection of Barth’s doctrine of election is mistaken.

Brunner does an excellent job showing here that the doctrine of double predestination it not a scriptural doctrine. In the theology of Zwingli especially, Brunner argues that the doctrine of predestination is a philosophical doctrine and not a biblical or theological one. It is based not on revelation, therefore, but is a kind of natural theology which works on philosophical terms!

Writing of Zwingli’s doctrine of double predestination, which Brunner distinguishes from Calvin’s doctrine as the least biblical of the two, he writes, “All this has nothing, nothing whatever, to do with Christian theology, but it is a rational metaphysic, partly stoic in character, and partly Neo-Platonist…” 3

Double predestination is a philosophical doctrine, a kind of speculation into the will of God. For this reason it is a form of natural theology—reading back into God what we perceive in mankind. This critique of double predestination is crushing, I believe, but Brunner does not stop there. He also presents a profound analysis of the scriptures showing how the doctrine of double predestination is unbiblical. For this I’ll quote Brunner extensively with a few comments in between. Enjoy!

Double Predestination: Unbiblical

Brunner writes,

“The Bible does not contain the doctrine of double predestination, although in a few isolated passages it seems to come close to it. The Bible teaches that all salvation is based upon the eternal Election of God in Jesus Christ, and that this eternal Election springs wholly and entirely from God’s sovereign freedom. But wherever this happens, there is no mention of a decree of rejection. The Bible teaches that alongside of the elect there are those who are not elect, who are ‘reprobate’, and indeed that the former are the minority and the latter the majority; but in these passages the point at issue is not eternal election but ‘separation’ or ‘selection’ in Judgment. Thus the Bible teaches that there will be a double outcome of world history, salvation and ruin, Heaven and Hell. But while salvation is explicitly taught as derived from the eternal Election, the further conclusion is not drawn that destruction is also based upon a corresponding decree of doom.“ 4

Essentially, Bruner argues here that while the scriptures do include an element of “reprobation” or “non-election”, these are not eternal decrees like election. Election may be eternal, but non-election is not, according to the scriptures. God did not eternally reject some and include others, according to Brunner, God elected from eternity but He did not reject from eternity. Brunner continues to bring out this point in terms of Israel’s history.

“The Bible teaches, it is true, that God is also at work in evil and in sin where men harden their hearts and betray the Highest; but this ‘working’ is not ascribed to an eternal decree, and the ‘hardening of heart’—particularly in the decisive case of Israel—is not conceived as irrevocable. Israel, which at present is hardened and therefore rejected, can—and indeed will—still be saved if it does not remain in a state of disobedience. The Bible teaches that Judas commits his act of treachery in order ‘that the scripture should be fulfilled’, but it does not say that this is the result of an eternal decree.“ 5

Rejection, for Brunner, is not a part of the eternal Divine decree, only election is. But rejection is still at play, if only in a temporary sense. From this Brunner turns to the chief scripture often used, Romans 9-11. Brunner rightly points out that the context here is not the election of the individual, but the election of Israel. He writes,

“The Ninth chapter of the Epistle to the Romans is usually regarded as the ‘locus classicus’ of the doctrine of a double predestination, and for this reason it requires very careful consideration. Hence it is extremely important to show very clearly the connexion of this chapter with the two which follow. They do not deal with the salvation and damnation of the individual, but with the destiny of Israel. Thus the point of view itself is entirely different from that of the doctrine of predestination.” 6

Following this Brunner points out three points of misunderstanding that are often at work in those who interpret Romans 9 for proof of double predestination. He writes,

“(a) As in the whole context, so also in the example of Jacob and Esau, in the movement of thought of the Apostle Paul, this is not an argument in support of a ‘double decree’, but it is an illustration of the freedom of God in His action in the history of salvation. When we read: ‘For the children being not yet born, neither, having done anything good or bad, that the purpose of God according to election might stand, not of works but of Him that calleth …’ this does not refer to a double ‘decretum’, but to the freedom of the divine election. Here there is no question of the eternal salvation of Jacob and the eternal doom of Esau; the point is simply the part which each plays in the history of redemption. Paul wishes to show that God chooses the instruments of His redemptive action, the bearers of the history of the Covenant, as He wills. The theme of this passage is not the doctrine of predestination, but the sovereign operation of God in History, who has been pleased to reveal Himself at one particular point in History, in Israel.

“(b) Likewise in the following verses Pharaoh is simply an historic redemptive instrument in the hand of God, that instrument which, through its ‘hardening’, must serve God’s purpose. There is no question here of his salvation or condemnation. All the argument is concentrated on one point: God has mercy on whom He will, and hardens whom He will. The point of the whole is the freedom of grace.

“(c) Finally, we come to the critical main passage, verses 19-22, the point in the whole Bible which comes closest to a doctrine of a double decree—and yet is separated from it by a great gulf. The parable of the potter and the clay, taken from Isaiah 28: 16 and Jeremiah 18: 6, expresses the absolute right of God to dispose of His creature as He chooses. The creature has no right to claim anything over against God; He may do with it what He wills. He does not have to account for His actions to anyone. God is the Lord, and His authority knows no limits.

“…The passage does not say that they have been created as vessels of wrath, still less that from all eternity they have been destined for this, but that, on account of their unbelief, they are ‘fitted unto destruction.’

“In any case, the ‘vessels of wrath’ mentioned in this passage are not the ‘reprobi’ of the doctrine of Predestination. Here, indeed, there is no mention of individuals as individuals at all, but the whole People of Israel is being discussed, and the point is not that the ‘People’ as a whole will be lost eternally, but that now, for the moment, they play a negative part in the history of salvation, which, in the future, after they have been converted, will become a positive one. The final issue of the judgment of wrath will be their salvation. Here, again, we notice that there is a remarkable ‘incongruity’ between those ‘on the left hand’ and those ‘on the right’, as in Matthew 25. The ‘vessels of wrath’ are designated by an impersonal passive, they are ‘ripe for destruction’. Thus it is explicitly stated that it is not God who has made them what they are. The linguistic phrase is deliberately in the passive, denoting a present condition, and can equally well be translated ‘ripe for condemnation’. Over against them stand the ‘vessels of mercy’ whom God ‘hath afore prepared unto glory’. In the first case no active subject, and no indication of an act of predetermination; in the second instance, an active Subject, God, and a clear indication of eternal election. Thus even in this apparently clearly ‘predestinarian’ passage there is no suggestion of a double decree!“ 7

Here in Romans 9 along with both the Old and New Testaments, there is absolutely no trace of the doctrine of God’s double decree! God’s election may be eternal, but God’s rejection cannot be, according to the witness of scripture.

Conclusions

There are some problems I have with Brunner’s doctrine of election, but here he presents an important insight into the Calvinist doctrine of double predestination: it simply is not a biblical doctrine!

I am part of several “reformed” groups on Facebook, and I am always frustrated to see how the Calvinists in them think that the bible is filled with this double decree. But it’s not! Instead, to prove this doctrine, a Calvinists must take their philosophical notion of God’s omnipotent decree, and they must inject it into the scriptures, ignoring context, thinking they’ve “proven” their doctrine. But here Brunner shows quite well how wrong they are. The bible simply does not contain a doctrine of double predestination, as it is found in the reformed tradition. There is a biblical doctrine of election, but there is not a biblical doctrine of eternal reprobation! Calvinists would do well to read Brunner’s critique in full context (it’s free online), or better yet, to read Barth’s brilliant doctrine of election in CD II/2! 8 I don’t think Brunner is completely right about his doctrine of election, but I do think his critique of double predestination as an unbiblical doctrine is spot on. Although, for a positive work on election, please refer to Karl Barth!

I hope you enjoyed these quotes from Brunner. Let me know in a comment what you think of his critique. Is he right in his assessment of Romans 9 and the doctrine of double predestination?

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Digital files for this volume and volume II are freely available on archive.org ↩For more on Barth and universalism see this article. ↩p. 323 ↩pp. 326-7 ↩p. 327 ↩p. 328 ↩pp.329-330 ↩I’ve written some on this here and here. ↩July 8, 2016

Live Slowly! says Jürgen Moltmann

I’m categorizing this one under “words to live by”! Jürgen Moltmann is not only an incredibly profound thinker and one of my favorite theologians: he is often an insightful and inspiring individual to learn life from. Here, Moltmann’s simple advice to modern men and women is this: Slow down!

I’m categorizing this one under “words to live by”! Jürgen Moltmann is not only an incredibly profound thinker and one of my favorite theologians: he is often an insightful and inspiring individual to learn life from. Here, Moltmann’s simple advice to modern men and women is this: Slow down!

It’s a rather long quote so I’ll let you read it yourself; though I must say I find this advice personally challenging, as I’m sure we can all learn to live slowly. In the age of instant social media interactions and fast paced everything it’s important we learn to live slowly! Moltmann is helpful here in showing us how we can be free to live slow lives and to stop trying to “play God” with our fast-paced living.

I hope you enjoy this quote as much as I do! This comes from Moltmann’s book God for Secular Society. (LINK) I enjoyed the book tremendously, and while it’s not necessarily a theological book there were many great passages in which Moltmann applies his theology to modern society. If you enjoy this quote, I’d recommend it!

“Modern men and women are ‘always on the go’, so wherever they are, they are always pressed for time. … Never before did human beings have as much free time as they have today, and never did they have so little time. Time has become ‘precious’ too, because ‘time is money’. The world offers us endless possibilities, but our life-span is brief. Consequently many people fall into a panic in case they should miss out on something, and they try to step up their pace of living. The utopia of overcoming space and time by way of high-speed trains, faxes and E-mail, Internet and videos, is a modern utopia. Everywhere we want to ‘keep up’ with things—the phrase is significant in itself. We want to be omnipresent in space and simultaneous in time. That is our new God-complex. …

“The modern revved-up human is fed by McDonald’s, poor devil. He has plenty of experiences, but actually experiences none of them because he wants to have seen everything and to hold on to it on slides or videos; but he doesn’t take it in or assimilate any of it. He has contacts in plenty but no relationships, because he ‘can’t stay’, but is always in a hurry. He gulps down his fast food, standing up if possible, because he is incapable of enjoying anything any more; for to enjoy something takes time, and time is what one doesn’t have. Modern men and women have no time, because they are always out to ‘save’ time. Because we can’t prolong our lives to any appreciable degree, we have to hurry in order to ‘get as much as possible out of life’. Modern men and women ‘take their own lives’ in the double sense of the phrase: by snatching at life, they kill it. The brevity of time is not diminished one single second by accelerated life. On the contrary, it is by being afraid of not getting one’s share and missing out on something that one falls short, and misses out on everything.

“We tourists have been everywhere but have got nowhere. There is always only enough time for a flying visit. The more we travel, and the more rapidly we chase after time, the more meagre the spoils. Everywhere we are just in transit. The person who lives more and more rapidly so as to miss nothing lives more and more superficially, and misses the depths of experience life offers. In that person’s world, everything is possible, but very little is real.

“It is probably our suppressed fear of death which makes us so greedy for life. Our individualized awareness tells us: ‘Death is the finish. You can’t hold on to anything, and you can’t take it with you.’ The unconscious fear of death shows itself in the stepped-up haste for living. In traditional societies, individuals felt themselves to be members of a larger whole: the family, life simply as such, or the cosmos. When the individual dies, the wider context in which he or she participated lives on. But modern individualized consciousness knows only itself, relates everything to itself, and therefore believes that death is the end of everything.

“Perhaps we can no longer go back to the old sense of belonging to a greater whole which endures when we disappear. But we can surrender our finite and limited life to the eternal divine life and receive our life from that. This is what happens when we experience communion with God in faith. To experience the presence of the eternal God brings our temporal life as if into an ocean which surrounds us and buoys us up when we swim in it. In this way the divine presence surrounds us from every side, as Psalm 139 says, like a wide space for living which even finite death cannot restrict. In this divine presence we can affirm our limited life and accept its limits. We will then become serene and relaxed, and will begin to live slowly and with delight.

“It is only the person who lives slowly who gets more out of life. It is only the person who eats and drinks slowly who eats and drinks with enjoyment. Slow food—slow life! Sten Nadolny’s book The Discovery of Slowness (ET 1981) rightly became a bestseller, and a comfort for harrassed modern minds and hearts. Only the very rich can squander time. Those who are assured of eternal life have time in plenty. Then we linger in the moment, and lay ourselves open to the intensive experience of life. …

“It is only the suppressed fear of death that makes us so hurried. The experienced nearness of death, by contrast, teaches us to live every moment with full intensity as an eternal moment. Our senses are sharpened in an undreamed-of way. We see colours, hear sounds, taste and feel as never before. The experience of death which we permit ourselves makes us wise for life and wise in our dealings with time. The hope of resurrection to which we hold fast opens up a wide horizon beyond death, so that we can leave ourselves time to live.“ 1

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Moltmann, J. (1999). God for a Secular Society: The Public Relevance of Theology (pp. 88–91). Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. ↩July 6, 2016

Emil Brunner’s “Revelation in Nature” and Karl Barth—Reconcilable?

I took up reading some of Emil Brunner’s theology this week. Brunner’s name is often brought up alongside other important thinkers of the 20th century such as Barth, Bultmann, and Tillich, so he is certainly an important figure to know. Though Brunner is perhaps most known within “Barthian” circles for his disagreements with Barth over natural theology in the infamous “Nature and Grace” debate. 1 Barth fiercely rejected Brunner’s acceptance of the revelation of nature, believing that any acceptance of any kind of natural theology ultimately opens the door to natural theology as a whole.

I took up reading some of Emil Brunner’s theology this week. Brunner’s name is often brought up alongside other important thinkers of the 20th century such as Barth, Bultmann, and Tillich, so he is certainly an important figure to know. Though Brunner is perhaps most known within “Barthian” circles for his disagreements with Barth over natural theology in the infamous “Nature and Grace” debate. 1 Barth fiercely rejected Brunner’s acceptance of the revelation of nature, believing that any acceptance of any kind of natural theology ultimately opens the door to natural theology as a whole.

So when I began reading Brunner I was surprised to discover just how close his theology is to Barth’s. I’d wrongly imagined them to be at complete odds with one another, but this is simply not the case. Brunner actually shares many of Barth’s insights, and Barth’s dedication to the revelation of Jesus Christ. But also, as we’ll soon see, Brunner surprisingly shares Barth’s fierce rejection of natural theology, if with some qualifications.

I’ve read elsewhere that some believe Barth’s rejection of Brunner’s theology is misplaced, 2 and that they probably agreed more than Barth liked to imagine. And furthermore, Barth’s later controversial acceptance of “Secular Parables” in CD/3.1 3 shows how Barth eventually sided with Brunner. He also regretted, in the end, in a letter written to Brunner before his death, his No to Brunner, writing, “tell him [Bruner] the time when I thought I should say No to him is long since past, and we all live only by the fact that a great and merciful God speaks his gracious Yes to all of us.”

It’s interesting, therefore, to examine in Brunner’s own words what his doctrine of “Revelation in Nature” actually is and how it relates to natural theology. This comes from his Dogmatics vol. 1, in a series of seven points which I will attempt to summarize here with selected quotes. Enjoy!

Seven Points on “Revelation in Nature”

First, Brunner makes a distinction between two questions, “the question of the revelation in Creation, and the question of man’s natural knowledge of God. … Now some theologians believed (mistakenly) that their denial of a theologia naturalis obliged them also to deny the reality of the revelation in Creation.” 4 He seems to have Barth in mind here, saying further that, “A theology which intends to remain true to the Biblical witness to revelation should never have denied the reality of revelation in Creation.” 5 So this is the distinction, for Brunner, that is essential: between natural theology and revelation in creation. One should be rejected, but one is biblically affirmed.

Second, Brunner points to the sinfulness of human beings as proof of a revelation in nature. Since we are sinners, since we cannot posit a genuine natural theology, but because we try—then there must be a revelation in Creation behind our attempts. Brunner writes, “Thus, on the one hand, the reality of the revelation in Creation is to be admitted, but, on the other hand, the possibility of a correct and valid natural knowledge of God is to be contested.“ 6 We cannot know God through nature, but that we try shows our sin and points to a revelation in creation behind our attempts.

Third, Brunner follows this point stating, “There is, it is true, no valid ‘natural theology’, but there is a Natural Theology which, in fact, exists. … Human beings, even those who know nothing of the historical revelation, are such that they cannot help forming an idea of God and making pictures of God in their minds.“ 7 Brunner points to the history of religions as proof for this. The fact that we are inevitably going to create ideas of God points to our sinfulness.

Fourth, this leads to why Brunner affirms a revelation in creation, by following Romans 1:19. He writes, “The fact that sinful human beings cannot help having thoughts about God is due to the revelation in Creation. The other fact, that human beings are not able rightly to understand the nature and meaning of this revelation in Creation is due to the fact that their vision has been distorted by sin.“ 8 The fact that we will always attempt to create concepts of God through natural means, for Brunner, seems to point to the existence of some kind of original revelation in nature, which, because of our sin, we cannot understand and will always distort.

Fifth, Brunner points out that the Apostles had no interest in explaining theoretically how sinful human beings do natural theology, but wanted to answer the question, “How should we address the man to whom the message of Jesus Christ is to be proclaimed?” 9 For Brunner, it is obvious that the existence of natural theology is inevitable, but that sinful humanity remains responsible even in their inability to properly make sense of revelation in nature. Thus, “The Fall does not mean that man ceases to be responsible, but that he ceases to understand his responsibility aright, and to live according to his responsibility.“ 10 Interestingly, Brunner here seems to think that this is the same conclusion Barth makes in CD III/1, that the image of God is not lost even after the fall of mankind. So it seems that Brunner is interested in pointing us to the responsibility of mankind to God even in their inability to interpret natural revelation. Ultimately, he writes, “It is sin which makes idols out of the revelation in Creation.” 11

Sixth, Brunner again points out that “The history of religions shows that mankind cannot help producing religious ideas, and carrying on religious activities.“ 12 This shows the confusion caused by sin, which leads to philosophical attempts to understand God.

Seventh, and finally, Brunner concludes that philosophy cannot form any true knowledge of God. Writing that, “the God of thought must differ from the God of revelation. The God who is ‘conceived’ by thought is not the one who discloses Himself; from this point of view He is an intellectual idol.“ 13 The gods of philosophy are ultimately “intellectual idols”. This is a clear rejection of philosophical, natural theology.

Conclusions

So here we have seven somewhat difficult points which briefly outline what Brunner understands about the relationship between natural theology and revelation in nature. The most insightful aspect here, for me, is the difference between natural theology and revelation in nature. Brunner seems to point towards the Image of God in human beings as the origin for this revelation in nature. This however, because of sin, is a revelation we cannot rightly understand and will always distort into natural theology. We are still responsible, as creatures created in Image of God, but we fail to live responsibility. Therefore we attempt in our sin to create a natural image of God, but this is only a distortion of the revelation of nature. So there is a revelation in nature, but it is one we cannot understand because of sin. We can only distort this revelation. Accordingly, natural theology is sin, a kind of intellectual idolatry. But this rejection of natural theology itself, for Brunner, seems to be at once the ultimate affirmation of revelation in nature.

This is my first attempt at understanding Brunner, so be aware that I may be misinterpreting him here. However, there seems to be a point of reconciliation between him and Barth, even in Brunner’s own admission. He points to CD III/1 for this, saying that Barth’s position there is close to what he is arguing here. They both agree that we should reject all natural theology, but Brunner seems to think that we can at once affirm a kind of “revelation in nature” linked with the image of God which remains in our being. This revelation in nature seems to be the cause of our natural theology, even if natural theology itself is sinful. Just as we remain the image of God, in spite of our sin, so there remains revelation in nature, in spite of our sinful and idolatrous attempts at natural theology.

Feel free to read this text yourself (pages 132-136) and make your own assessment. I’m not sure I’m convinced yet by Brunner’s argument, but it seems interesting nonetheless. And certainly it seems that there is more to this debate than the initial “No” of Barth to Brunner! As I keep reading Brunner’s Dogmatics I will pay special attention to how he develops this idea further, if he does at all.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

See this book for the debate. ↩See this article ↩My friend over at Postbarthian wrote up a great article on Barth’s acceptance of Secular Parables, click here. ↩p. 132 ↩p. 133 ↩p. 133 ↩p. 133 ↩p. 134 ↩p. 134 ↩p. 135 ↩p. 135 ↩p. 135 ↩p. 136 ↩June 30, 2016

Karl Barth on Universalism

Karl Barth responds to the question of universalism directly, though briefly, in his short book The Humanity of God. His response to the question of universalism is brilliant, and perhaps one of the best pictures of how he understood universalism. It’s an often debated subject: whether or not Barth was a universalist. 1 I personally would argue that he is not, but here, in Barth’s own words, is a beautiful response to the question.

Karl Barth responds to the question of universalism directly, though briefly, in his short book The Humanity of God. His response to the question of universalism is brilliant, and perhaps one of the best pictures of how he understood universalism. It’s an often debated subject: whether or not Barth was a universalist. 1 I personally would argue that he is not, but here, in Barth’s own words, is a beautiful response to the question.

“Does this mean universalism? I wish here to make only three short observations, in which one is to detect no position for or against that which passes among us under this term.

“1. One should not surrender himself in any case to the panic which this word seems to spread abroad, before informing himself exactly concerning its possible sense or non-sense.

“2. One should at least be stimulated by the passage, Colossians 1:19, which admittedly states that God has determined through His Son as His image and as the first-born of the whole Creation to ‘reconcile all things to himself,’ to consider whether the concept could not perhaps have a good meaning. The same could be said of parallel passages.

“3. One question should for a moment be asked, in view of the ‘danger’ with which one may see this concept gradually surrounded. What of the ‘danger’ of the eternally skeptical-critical theologian who is ever and again suspiciously questioning, because fundamentally always legalistic and therefore in the main morosely gloomy? Is not his presence among us currently more threatening than that of the unbecomingly cheerful indifferentism or even antinomianism, to which one with a certain understanding of universalism could in fact deliver himself? This much is certain, that we have no theological right to set any sort of limits to the loving-kindness of God which has appeared in Jesus Christ. Our theological duty is to see and understand it as being still greater than we had seen before.” 2

What a fantastic answer!

We might break down these three points like this. First, Barth argues that we should avoid the gut-reaction common to the term universalism (especially among evangelicals). I take this to mean that Barth wants us not to immediately dismiss the idea as heretical just because that’s what we’ve been told about it. Second, if we take the scriptures seriously we cannot help but at least find ourselves stimulated by the idea of universalism, as there are certainly universalist tendencies in the scriptures. And finally, universalism, at the end of the day, is far more preferable over doom-and-gloom pessimism! That is perhaps the more serious error. But if we’re going to error, isn’t it better to error on the side of God’s loving-kindness? to “understand [God’s love] as being still greater than we had seen before”, rather than to error on the side of pessimism in which universalism is dogmatically impossible? The possibility of universalism may not be a perfect one, but it is a far better alternative to dogmatic pessimism!

All these three points could, in other words, be summarized by Barth’s most famous statement on universalism, “I don’t teach it [universalism], but I don’t not teach it.” Barth said it himself: he takes no position either for or against universalism.

It is this emphasis that I find so compelling, especially since this subject is all too often dealt hastily with cheap and quick yes or no answers. I admire that Barth leaves the question open and unanswered. It’s a sign of respect for God, I believe. Ultimately, I think this is the best way to understand Barth’s position towards universalism: it is an open, unanswerable question. He cleverly is giving us a non-answer here. I don’t think he was afraid of the question, I think Barth genuinely considered it unanswerable, as any attempt to dogmatically answer it is, ultimately, I think, an attempt to play God. Who will know in the end what will take place? Only God can, and will, answer the question of universalism. But we can and should have hope for it, or at least not be so quick to dismiss it as many do today!

It is an open question, one which we can hope for, but never dogmatically assert. The error of dogmatic assertion is on both sides here, as Barth rightly warns us. To dogmatically claim that salvation/redemption is not universal is just as problematic as to dogmatically claiming that it is universal. We can hope for it, but we cannot try and “play God” and thus divine what the outcome will be. Although, as Moltmann pointed out, our hope is a “certain” hope, founded on the cross of Christ. So it is not merely a “wishing for the best,” but a definite hope in what God has done in Jesus Christ and will do for all humanity.

What do you think of Barth’s answer? Is this a brilliant way to answer the question, or just a nonsense answer? In your reading of Barth, would you say he’s a universalist? Leave me a reply in the comments!

(P.S. The Humanity of God is this month’s free book for those of you in my Readers Group! If you’re not a part of my mailing list, you should be. You get free books like this each month, plus my book Where Was God free right away! Sign up here.)

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

One of the best articles on the subject is Roger Olsen’s. ↩The Humanity of God, John Knox Press, 1960, pp. 61-2 ↩June 29, 2016

Karl Barth on the Humanity of God

Karl Barth’s The Humanity of God was one of his first books I read. I loved it, but in retrospect I probably understood very little of it. So today I decided to read it once again, and since it’s a rather short book I’ve nearly read it all in one sitting! I’m reminded of all the reasons why I love the theology of Karl Barth as I read: not that Barth himself is the focus, but that I find myself time and time again drawn to worship God! That, for me, is the ultimate test for what “good” theology actually is.

Karl Barth’s The Humanity of God was one of his first books I read. I loved it, but in retrospect I probably understood very little of it. So today I decided to read it once again, and since it’s a rather short book I’ve nearly read it all in one sitting! I’m reminded of all the reasons why I love the theology of Karl Barth as I read: not that Barth himself is the focus, but that I find myself time and time again drawn to worship God! That, for me, is the ultimate test for what “good” theology actually is.

I wanted to share a notable section from the book, probably it’s central part. It’s a rather long quote, followed by several shorter quotes to drive the point home and clarify what Barth is getting out. Here Barth is arguing what he refers to as the “humanity” of God, a rather difficult concept for those unfamiliar with Barth. But what he means by this is something I will simply let him explain for himself, though its worth noting how this is a development upon what Barth argues in CD IV/1 on the condescension of God in Jesus Christ and the exaltation of man in Jesus Christ (§59.1, “The Way of the Son of God into the Far Country”). If you’re looking for even further clarity into what Barth means, go read that section. It’s a revolutionary concept well worth taking the time to understand.

But without further ado, please enjoy! Bold text is mine for emphasis; italics are in the original.

(As a quick side-note: The Humanity of God is July’s free book of the month, which I always send to my Readers Group on the first of every month. When you’re a subscriber, every month you get a great free book, plus you get my book right away—Where Was God, a short and approachable introduction Moltmann’s theodicy! Don’t miss out! Sign up here.)

“Who God is and what He is in His deity He proves and reveals not in a vacuum as a divine being-for-Himself, but, precisely and authentically in the fact that He exists, speaks, and acts as the partner of man, though of course as the absolutely superior partner. He who does that is the living God. And the freedom in which He does that is His deity. It is the deity which as such also has the character of humanity. In this and only in this form was—and still is—our view of the deity of God to be set in opposition to that earlier theology. There must be positive acceptance and not unconsidered rejection of the elements of truth, which one cannot possibly deny to it even if one sees all its weaknesses. It is precisely God’ deity which, rightly understood, includes his humanity.

“How do we come to know that? What permits and requires this statement? It is a Christological statement, or rather one grounded in and to be unfolded from Chrstology. […] In Jesus Christ, as He is attested in Holy Scripture, we are not dealing with man in the abstract: not with the man who is able with his modicum of religion and religious morality to be sufficient unto himself without God and thus himself to be God. But neither are we dealing with God in the abstract: not with one who in His deity exists only separated from man, distant and strange and thus non-human if no indeed an inhuman God. In Jesus Christ there is no isolation of man from God or of God from man. Rather, in Him we encounter the history, the dialogue, in which God and man meet together and are together, the reality of the covenant mutually contracted, preserved, and fulfilled by them. Jesus Christ is in His one Person, as true God, man’s loyal partner, and as true man, God’s. He is the Lord humbled for communion with man and likewise the Servant exalted to communion with God. He is the Word spoken from the loftiest, most luminous transcendence and likewise the Word heard in the deepest, darkest immanence. He is both, without their being confused but also without their being divided; He is wholly the one and wholly the other. Thus in this oneness Jesus Christ is the Mediator, the Reconciler, between God and man. Thus He comes forward to man on behalf of God calling for and awakening faith, love, and hope, and to God on behalf of man, representing man, making satisfaction and interceding. Thus He attests and guarantees to man God’s free grace and at the same time attests and guarantees to God man’s free gratitude. Thus He establishes in His Person the justice of God vis-a-vis man and also the justice of man before God. Thus He is in His Person the covenant in its fullness, the Kingdom of heaven which is at hand, in which God speaks and man hears, God gives and man receives, God commands and man obeys, God’s glory shines in the heights and thence into the depths, and peace on earth comes to pass among men in whom He is well pleased. Moreover, exactly in this way Jesus Christ, as this mediator and Reconciler between God and man, is also the Revealer of them both. We do not need to engage in a free-ranging investigation to seek out and construct who and what God truly is, and who and what man truly is, but only to read the truth about both where it resides, namely, in the fullness of their togetherness, their covenant which proclaims itself in Jesus Christ.

“Who and what God is—this is what in particular we have to learn better and with more precision in the new change of direction in the thinking and speaking of evangelical theology, which has become necessary in the light of the earlier change. But the question must be, who and what is God in Jesus Christ, if we here today would push forward to a better answer.” 1

“In Jesus Christ man’s freedom is wholly enclosed in the freedom of God.” 2

“God’s deity is thus no prison in which He can exist only in and for Himself. […] God’s deity does not exclude, but includes His humanity.” 3

“In Him [Jesus Christ] the fact is once for all established that God does not exist without man.” 4

“In this divinely free volition and election, in this sovereign decision (the ancients said, in His decree), God is human. His free affirmation of man, His free concern for him, His free substitution for him—this is God’s humanity.” 5

“If Jesus Christ is the Word of Truth, the ‘mirror of the fatherly heart of God,’ (Luther) then Nietzsche’s statement that man is something that must be overcome is an impudent lie.” 6

“On the basis of the eternal will of God we have to think of every human being, even the oddest, most villainous or miserable, as one to whom Jesus Christ is Brother and God is Father; and we have to deal with him on this assumption.” 7

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

The Humanity of God, John Knox Press, 1960, pp. 45-7 ↩P. 48 ↩P. 49 ↩P. 50 ↩P. 51 ↩P. 51-2 ↩P. 53 ↩June 27, 2016

Fundamentalism as Fear (Tillich)

I’ve been reading recently Paul Tillich’s (in)famous book The Courage to Be. I have many suspicions about Tillich’s theology, and, from what little I’ve read of him, I inherently feel predisposed against his general method, as well as many of his conclusions. However, he is still an influential thinker and well worth the effort it takes to engage with. And sometimes he has some rather interesting and helpful things to say.

I’ve been reading recently Paul Tillich’s (in)famous book The Courage to Be. I have many suspicions about Tillich’s theology, and, from what little I’ve read of him, I inherently feel predisposed against his general method, as well as many of his conclusions. However, he is still an influential thinker and well worth the effort it takes to engage with. And sometimes he has some rather interesting and helpful things to say.

I will note too that I appreciate Tillich’s task: to make God relevant for today’s age. I am just afraid he took this too far and tried to relativized the entire Christian faith. But I appreciate his efforts, and plan to engage more with his thought as I read this book (and his Systematic Theology, which I’m planning to read sometime in the future).

This quote sums up well what I do appreciate about Tillich: “I hope for the day when everyone can speak again of God without embarrassment.” It seems to me a noble task, to make God relevant for today’s world, but the way he sought to do this is one I cannot condone.

Regardless, while I was reading The Courage to Be, I came across an insightful analysis of fundamentalism. Fundamentalism, especially in America, is a serious problem for Christianity. It is a way of thinking, more than anything else, which holds to strict black and white, either/or dogmas. For a fundamentalist, questions are not welcome, or maybe it’s better to say, questioning the “fundamentals” is not welcome, no matter how logical or factually based those questions are. It depends on who you ask what these “fundamentals” are actually, but the classic ones for Christianity tend to include biblical inerrancy, a literal seven day creation, penal substitutionary atonement, and, especially in modern times, homosexuality as a sin.

I’m not saying these are correct of incorrect just because they are the fundamentals of fundamentalists. But the main problem with fundamentalism is that it is a close-minded, black and white way of thinking about truth. Questioning these fundamentals will immediately lead to the application of the (over used) label “heretic”. So it doesn’t matter what the fundamentals are, the fundamentalist is one who cannot question them, and accordingly, who cannot allow anyone else to question them either! This is, as Tillich says in a moment, a kind of defense mechanism in reaction to modern and postmodern claims. But it is an over-reaction in most cases.

In the final analysis fundamentalism worships idols of its own making. Anything beyond questioning is an idol. Which does not mean that there is no such thing as truth, but that the truth is true no matter how harshly you question it; true remains true. Truth does not need a defender if it is true, fundamentalism decides beforehand what is true and rejects any attempt to verify or reject that claim.

But why, within fundamentalism, is there no room left for questioning or doubting “the fundamentals”? Paul Tillich sheds light on the matter:

“Fanaticism [fundamentalism] is the correlate to spiritual self-surrender: it shows the anxiety which it was supposed to conquer, by attacking with disproportionate violence those who disagree and who demonstrate by their disagreement elements in the spiritual life of the fanatic which he must suppress In himself. Because he must suppress them in himself he must suppress them in others. […]

[The fundamentalist] flees from his freedom of asking and answering for himself to a situation in which no further questions can be asked and the answers to previous questions are imposed on him authoritatively. In order to avoid the risk of asking and doubting he surrenders the right to ask and to doubt. He surrenders himself in order to save his spiritual life. He ‘escapes from his freedom’ (Fromm) in order to escape the anxiety of meaninglessness. Now he is no longer lonely, not in existential doubt, not in despair. He ‘participates’ and affirms by participation the contents of his spiritual life. Meaning is saved, but the self is sacrificed.” 1

In other words, fear; the fear of meaninglessness. There is always this fear in the questions of doubt which lead to new ways of thinking about a problem, a fear that in questioning our presuppositions our worldview will effectively become empty. But if we wish to seek the truth earnestly, we must risk asking hard questions and at times doubt our presuppositions in order to arrive at the truth. This isn’t necessarily Tillich’s point, but it’s something I’ve thought of before in regards to fundamentalism. Any system of thinking that stands above criticism is an idol.

But there is a danger here; there is the equal error of falling into a perpetual state of doubt. But this too is ultimately another defense mechanism in the form of nihilism, which at its core seeks to negate all propositions as meaningless and empty. But questions are a good thing; curiosity is a blessing. It takes risk to ask hard questions. But the adventure of discovery and of truth is well worth the effort. And in the end, truth ultimately is an eschatological term. We will never perfectly acquire truth until the eschaton. And how we all will laugh at our so-called “fundamentals” on that day!

Edit:

I’ve just found a fantastic quote which sums up quite well my difficulties with Paul Tillich, and I thought to include it here:

“[Paul Tillich’s] problem and danger, to put the matter simply, is the lack of a consistent focus on the revelation of God in Jesus Christ” – Alexander McKelway

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

pp. 49-50 ↩June 26, 2016

Karl Barth on Grace and our Response (with Help from Ansell)

A few days ago I wrote my review of Nicholas Ansell’s fantastic book on the universalism of Jürgen Moltmann, aptly entitled The Annihilation of Hell (LINK). I also wrote some reflections on how, as I learned from Ansell, Moltmann argued for a “certain” hope, over against a “wishing for the best” or even a dogmatic kind of universalism. I found this book compelling, and it goes to show just how compelling it was for me when even after finishing it I am left thinking again and again about what I learned.

A few days ago I wrote my review of Nicholas Ansell’s fantastic book on the universalism of Jürgen Moltmann, aptly entitled The Annihilation of Hell (LINK). I also wrote some reflections on how, as I learned from Ansell, Moltmann argued for a “certain” hope, over against a “wishing for the best” or even a dogmatic kind of universalism. I found this book compelling, and it goes to show just how compelling it was for me when even after finishing it I am left thinking again and again about what I learned.

I was looking through my notes on the book, and one quote stood out to me that I wanted to share here. In this, Ansell is answering how Moltmann’s kind of universalism might answer the problem of human freedom. It’s often said that universalism negates the human response, falling prey to a kind of determinism that turns free humanity into a robotic partner to God’s grace. But here Ansell points to Moltmann’s alignment with Barth’s theology of grace and response, specifically of human freedom in the response to grace, as a way forward past this difficulty. In simple terms, Barth argued that we are free because God makes us free; we are free in God’s freedom. And here Ansell expounds this quite beautifully as it relates to Moltmann’s kind of universalism. Enjoy!

(Italics are from the original, bold is mine for emphasis. Brackets “[ ]” are added for clarity.)

“A great strength of Barth’s theology, I suggest, is his realisation that God’s grace lies beyond all human power and control. It is a gift that empowers. Our very existence is graced. Theology must contend with what Matthew Fox has called ‘Original Blessing.’ Barth puts it well: ‘Creation is the work of the truly free, truly undeserved grace of the one true God, both as an act and in its continuance.’

“The gift precedes our ability to respond. Our capacity to respond to the gift of Life is itself a gift of Life. We don’t choose to be born. Our capacity to choose is itself born due to, thanks to, those who have helped bring us into existence. If we may speak here of the giving of others then such giving may be seen as mediating the giving of God. Gift precedes response. A response can embody/express the gift, can be gifted, can rest in something beyond, or prior to, itself. But the gift is beyond our control, grasp, understanding. It is never exhausted in our responses. Our ‘being’ precedes our ‘doing’. Our ‘being’ is not an ‘essence’ within. The gift/call of who we are is prior to, more than, what we make of ourselves. 1

…

“In Barth’s position, God’s Yes to creation embraces a humanity that cannot naturally say Yes to God. In grace, we respond to God’s freedom and find our true freedom. 2

…

“Perhaps this dilemma is not insoluble [the universalist dilemma of human freedom/response]. A case for a ‘covenantal’ universalism can be made, I suggest, if we root the claim that ‘all respond to God’s grace in God’s grace’ in the conviction that we are created for Life and for God ‘from the beginning’. Responding to God’s creational grace is the warp and woof of our authentic nature. Redemption is the reaffirmation, liberation, and restoration of our true nature, rather than being a creatio ex nihilo. Our true nature is a gift/promise that responds to the gift/promise. In the context of grace, our true nature, we might say, ‘comes into its own’. This is not autonomy or heteronomy. Our response to the gift/call of Life is our response, our life. This is freedom truly defined. Freedom is not ‘doing what we want’. Freedom is not doing ‘what God wants’ instead of ‘what we want’. Freedom is faithfully keeping covenant with the God of Life in the way we choose. A universal salvation that is non-coercive must, in my view, affirm the fact that we are made for God, made for Life, to respond to Life, to initiate Life, to live (and without God there is no life) by being who we are (who we are called to be). In this sense, salvation (including universal salvation) reveals our very nature.

“Redemptive grace reaffirms and re-offers the gift of life. Graced nature ‘naturally’ responds by God’s grace to God’s grace. This is neither divine monergism nor syn-ergism (in the pejorative sense). Our working out of the gift-promise of life is covenantal. It is not a ‘work’ of the kind the reformers opposed. In covenant with God, our work is also God’s work while remaining thoroughly our own (in a non-possessive, non-autonomous sense). 3

…

“God is the God of creation. Creation is the creation of God. To love God is to love life. It is to find and celebrate our freedom. Only with God may we be human.” 4