Stephen D. Morrison's Blog, page 11

June 24, 2016

Jürgen Moltmann’s “Universalism of the Cross” (A Book Review of “The Annihilation of Hell” by Nicholas Ansell)

Book: The Annihilation of Hell: Universal Salvation and the Redemption of Time in the Eschatology of Jürgen Moltmann by Nicholas Ansell (2013). (Amazon link)

Book: The Annihilation of Hell: Universal Salvation and the Redemption of Time in the Eschatology of Jürgen Moltmann by Nicholas Ansell (2013). (Amazon link)

Publisher: Cascade Books, an imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Jürgen Moltmann is one of my favorite theologians, and so I was delighted to have the opportunity to read and review Nicholas Ansell’s book The Annihilation of Hell from the kind people at Wipf and Stock publishers. Thank you!

This book is a sympathetic engagement with Moltmann’s eschatology, specifically focusing on universal salvation and the nature of time in Moltmann’s theology. Generally speaking, I greatly enjoyed reading this book and appreciate the tremendous effort Ansell has put forward in it. I recommend it to anyone interested in the theology of Jürgen Moltmann, especially in how it pertains to universalism.

Ansell’s critique

Ansell presents an overview of his work in a summary at the end of the book. He writes,

This study is an engagement with the theme of universal salvation as viewed within the overall structure of Moltmann’s theology, eschatology, and theocosmogony. Consonant with Moltmann’s understanding, the main title, The Annihilation of Hell, refers to the overcoming of Hell as our eschatological hopes are realised, whilst at the same time alluding to Hell’s own annihilative power in history—a power with which hope must contend. For Moltmann, Hell is the nemesis of hope. Yet hope clings to the certainty that God in Christ has embraced all things, even death and Hell, so that creation may participate in the divine Life of the Age to Come. (P. 424)

Prior to this remark, Ansell gives an overview of his general critique of Moltmann’s position.

Although I accept Moltmann’s ‘universalism of hope’ and greatly appreciate his ‘universalism of the cross’, his ‘theocosmogony of the cross’ is a very different story. (P. 372)

Ansell argues quite well in this book that Moltmann’s universalism of hope and of the cross is a commendable one, but he is critical of his theocosmology. Particularly, he is critical of how Moltmann seems to blur the line between creation and fall in his usage of zimzum, and in turn of his negative assessment of creation (and thus of time). Ansell proposes a way forward which I find insightful and constructive. He spends a great deal of time in the book dealing with the nature of time. It may very well be time well spent (see what I did there?), but I was less interested in this section than in his overall affirmation of Moltmann’s universalism.

In this review, as the title suggests, I want to focus on what Ansell says positively about Moltmann’s universalism. Because, frankly, most of what Ansell had to say negatively about Moltmann’s theocosmology I had not picked up on in my reading of his work. Most of his insights were great in this regard: that I felt as if I was learning a new way of reading Moltmann. This is the most notable factor of his carefully nuanced critique. (And from this I am challenged that I need to read Moltmann again, and perhaps more carefully!) But obviously this also means I would have difficulty engaging with Ansell’s criticism of these ideas. Though I do commend his work and think he is certainly right about much of his critique.

(And it is generally a constructive critique, as Ansell offers many helpful alternatives which he feels strengthen Moltmann’s universalism. I’m just not as well versed in the philosophy of time as Ansell is.)

Ansell’s affirmation

A better understanding of Moltmann’s universalism of the cross is the primary gain I take from this book. The key feature that I found commendable was how Ansell placed Moltmann’s universalism into conversation with modern theologies, asking: Does Jürgen Moltmann’s eschatology present a kind of universalism which might be approachable for today’s evangelical theology? Ansell offers a supportive yes.

For Moltmann, universal salvation is not a dogmatic assertion, but it is a certain hope. (I’ve written more on this here.) It is a certain hope not because of theological deduction, but because of what God has done in Jesus Christ, specifically because of what has taken place in His death and descent into hell. For Moltmann, then, universalism is best argued from the standpoint of the crucified Christ. Moltmann writes in his famous work, The Crucified God, that “the theology of the cross is the true Christian universalism.”

For Moltmann, the basis of universal salvation is the cross of Jesus Christ, who was buried and descended into hell. In this way God may truly become “all in all”, because even in hell there is hope because there is the presence of Christ.

For this reason, Ansell calls Moltmann’s universalism “pre-theological”. He writes what follows, summarizing the difference between a dogmatic universalism and a merely hopeful one (apart from the substance of the cross):

A universalism of hope, I was thereby suggesting, is neither a dogma nor a ‘nice idea’. Those who, in looking forward to God’s final victory over evil, find themselves looking forward in hope and confidence to a ‘universal’ salvation are convinced of something that others cannot be convinced of unless—or until—they come to share in that hope. In my view, a conviction of this kind, which is pre-theological and pre- doctrinal in character, is legitimate—at least in principle—even if those who hold to it cannot justify it theologically. Moltmann himself captures this pre-theoretical confidence well when he describes his own position as “a universalism of hope which is not a doctrine . . . but is a presupposition.” This is a hope I share and a ‘universalism’ I accept. (P. 211)

That in the end all will be redeemed is not the theological doctrine Moltmann claims, but rather it is his theological presupposition. As I’ve written elsewhere, for Moltmann the fact that Christ has descend into hell means hope for the redemption of all creation. The famous warning over Dante’s Inferno, “Abandon all hope…”, is deemed null and void in the light of Christ’s cross and descent into hell. Because if even in hell there is hope, we can presuppose that in the end all will be saved. This is not because we think God should or must do this, but because of what God has done in Jesus Christ and His cross we can presuppose this as the ultimate goal of redemption.

Moltmann’s universalism, therefore, is deeply connected with the whole of his theological project, which is centered upon the sufferings of Jesus Christ on the cross. Hope for the universal salvation of the cosmos is affirmed, according to Moltmann, on the cross.

Beyond this focus, Ansell also shows how Moltmann navigates the two major arguments often spoken against universalism. First, that it negates the freedom of mankind, and second, that it negates the freedom of God. Dogmatic universalism perhaps does this, but Moltmann’s universalism of the cross is not stuck in this same position. Dogmatic universalism is often plagued with a sort of determinism, in which ultimately all will be saved because God “must” save and we “must” be saved. The problems of this position are address well and their relation to Moltmann’s position are very insightful. It is one of my favorite aspects of this book, that Ansell strives most of all to engage Moltmann with the contemporary theology of both the Arminian and Calvinist positions. Moltmann’s universalism of the cross untangles itself from this dual problem of freedom in an admirable way. Thus, Ansell seems to conclude that Moltmann’s universalism, with some alterations, is one which the Christian community at large might engage and possibly accept as viable.

Conclusions

Ansell’s book is an excellent and nuanced study on Moltmann’s eschatology and his universalism of the cross. I look forward to further work from Ansell, as he wrote in a clear yet erudite manner. This book is approachable for most informed readers, though I do recommend, if you’re interested in reading it, that you have at least a basic understanding of Moltmann’s theology beforehand. (It’s especially helpful if you’ve read God in Creation, The Coming of God, and Theology of Hope.)

This book helped me see many aspects of Moltmann’s theology I may have missed otherwise, and I plan to revisit some of the key books he mentions to study further Moltmann’s thought. This book has also helped me come to greater terms with Moltmann’s universalism and the commendable features of it. I appreciate far more Moltmann’s theology and especially his kind of universalism, which I personally find quite viable for the church today.

You can buy the book here from Amazon or directly from the publisher.

Like this article? Share it!

June 20, 2016

Universalism: A “Certain” Hope (Jürgen Moltmann)

I’m currently reading Nicholas Ansell’s book on the universalism of Jürgen Moltmann, entitled The Annihilation of Hell: Universal Salvation and the Redemption of Time in the Eschatology of Jürgen Moltmann. (LINK) So far I am enjoying it tremendously, and I have no doubt that I will eventually have more to say about it later, along with a full review of the book once I’ve finished.

I’m currently reading Nicholas Ansell’s book on the universalism of Jürgen Moltmann, entitled The Annihilation of Hell: Universal Salvation and the Redemption of Time in the Eschatology of Jürgen Moltmann. (LINK) So far I am enjoying it tremendously, and I have no doubt that I will eventually have more to say about it later, along with a full review of the book once I’ve finished.

But from the first chapter there was an interesting idea Ansell brings up that I wanted to share here. I have said before that I am not a universalist, though I could rightly be called a “hopeful” one. With Balthasar I believe it is not only permissible but essential that we hope for all humanity, that in the end all will be redeemed. We cannot dogmatically assert this, but we can and should hope for it.

This tension between dogmatic and hopeful universalism, one of which is heretical and the other of which is acceptable and encouraged, is something which Ansell clarifies through highlighting what he calls Moltmann’s “certain hope”. He writes:

This ‘certain hope’, as I have referred to it, and the “confession of hope” with which he [Moltmann] brings his discussion to a close, need to be carefully distinguished from the ‘hopeful’ universalism that finds approval in The Mystery of Salvation. In the latter, the universal salvation we ‘hope’ for is something that we desire, without knowing for sure what God will finally be able to achieve in the face of human freedom. Because there is no way that we can be certain, in this understanding, the best we can do is ‘hope’ for the best. ‘Dogmatic’ universalism is thus inappropriate. Moltmann’s ‘theology of hope’ is very different. While he would certainly agree that God’s eschatological Judgment is still to come, and is thus not something we can describe, at the same time, he insists that because the revelation of God’s purposes in the Christ event has already taken place, a hope that is rooted in the cross is not simply an expression of what we would like to happen. Given God’s decisive action in Christ, we can be confident of the outcome: “What Christ accomplished in his dying and rising is proclaimed to all human beings through his gospel and will be revealed to everyone and everything at his appearance.” The “confession of hope,” as articulated by Christoph Blumhardt, can and should be preached with conviction. This has nothing to do with merely ‘hoping for the best’. For hope, in Moltmann theology, provides the way to certainty. And the cross provides the way to hope. In “submerg[ing] ourselves in the depths of Christ’s death on the cross,” Moltmann writes, “… we find the certainty of reconciliation without limits.” 1

Here we see a distinction between hope as merely “hoping for the best,” and hope as certainty grounded upon God’s actions and will in Jesus Christ on the cross. While this does not affirm dogmatic universalism, it does refine what we mean by “hopeful” universalism. It is not the hope of what we want, over and against what God wants; it is a hope based on the certainty that this is what God wants for the human race, as revealed in Christ and His cross. God wills redemption, not destruction, salvation, not damnation, restoration, not abandonment.

This certain hope is not the hope of wishful thinking, but hope in the certainty of God Himself, of God’s consistency with Himself, and certainty in His work in Jesus Christ. We hope with certainty because, as Peter writes, God wills that none shall perish. (2 Peter 3:9) And furthermore, God has acted with this purpose in mind. Our hope is certain because it is a hope not against God’s will and work in Jesus Christ, but with it! Thus it is a certain hope.

I am looking forward to reading more from Ansell and this book. I highly recommend this book if Moltmann’s eschatology interests you, especially as it pertains to universal salvation. You can buy the book here.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Nicholas Ansell, The Annihilation of Hell, 2013 Cascade Books, pp. 39-40. (Bold text mine for emphasis) ↩June 11, 2016

Barth on “Adam and Christ” vs. “Christ and Adam”

The following is a quote from Karl Barth’s short book on Romans 5. In this Barth argues that the proper order we have to think through is not “Adam and Christ” but “Christ and Adam”. That is to say, Christ first then Adam, and therefore Adam only in the light of Christ. This reframes the doctrine of sin and the doctrine of atonement by placing the justification of the sinner first before the knowledge of sin and of the sinner, because, as Barth later argues in the Church Dogmatics, we can only know sin in the light of the One who conquered it! Furthermore, as best shown here, Barth also argues that the fundamental nature of human beings is not in Adam but in Christ. Since this order is reverse, since we know Adam only in the light of Christ, we likewise can only know ourselves and human nature in the light of Christ. (Bold text is mine.)

“The meaning of the famous parallel (so called) between ‘Adam and Christ,’ which now follows, is not that the relationship between Adam and us is the expression of our true and original nature, so that we would have to recognize in Adam the fundamental truth of anthropology to which the subsequent relationship between Christ and us would have to fit and adapt itself. The relationship between Adam and us reveals not the primary but only the secondary anthropological truth and ordering principle. The primary anthropological truth and ordering principle, which only mirrors itself in that relationship, is made clear only through the relationship between Christ and us. Adam is, as is said in v. 14, typos toumellontos, the type of Him who was to come. Man’s essential and original nature is to be found, therefore, not in Adam but in Christ. In Adam we can only find it prefigured. Adam can therefore be interpreted only in the light of Christ and not the other way round.“

“For Christ who seems to come second, really comes first, and Adam who seems to come first really comes second. In Christ the relationship between the one and the many is original, in Adam it is only a copy of that original. Our relationship to Adam depends for its reality on our relationship to Christ. And that means, in practice, that to find the true and essential nature of man we have to look not to Adam the fallen man, but to Christ in whom what is fallen has been cancelled and what was original has been restored. We have to correct and interpret what we know of Adam by what we know of Christ, because Adam is only true man in so far as he reflects and points to the original humanity of Christ.“

(Christ and Adam: Man and Humanity in Romans 5, pp. 39-40 and pp. 74-5, Collier Books ed. 1962)

Like this article? Share it!

June 10, 2016

Karl Barth’s Translation of Ephesians 1

A few days ago I posted about reading Ross Wright’s PhD dissertation in which he translates Karl Barth’s lectures from 1921-1922 on Ephesians. I wrote there about Barth’s affirmation of both Ephesians and Colossians’ Pauline authorship.

I’ve since finished reading these lectures, and wanted to share today Barth’s translations of Ephesians 1. I say translations (plural) because Barth translated Ephesians 1 twice, and both are given at the end of his lectures in Wright’s dissertation. The first is a transition given for sermons given on Ephesians 1, and the second is an academic translation for his lectures on Ephesians. Accordingly, the academic translation is more, well, academic, with verse numbers included, and the one prepared for the sermon is presented more simply without verse numbers.

Here I’ve reposted both for your enjoyment. First, Barth’s translation for a sermon by itself, and second, is Barth’s Academic translation run parallel next to the ESV version of this text. Enjoy!

(These come from this paper, translated by Ross Wright in 2007. Italics come from original source.)

Translation for a Sermon in 1921

Paul, an apostle of Jesus Christ by the will of God, to the saints in Ephesus and the believers in Christ Jesus. Grace be with you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.

Praised be God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us with every spiritual blessing of the heavenly world in Christ.

In him he chose us before the foundations of the world were laid that we might be holy and blameless in him. In love he chose so that we might be his children through Jesus Christ according to his good pleasure to the praise of the glory of his grace which he lavished upon us in his beloved.

In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of sins according to the abundance of his grace, which is amply given to us as complete wisdom and insight. He has let us know the mystery of his will, to carry out according to his good pleasure the reuniting of all things in Christ in the fullness of time as he planned, things heavenly and things earthly in him.

In him we have become heirs and were chosen for this according to the purpose of the one who accomplishes everything according to the intention of his will, so that we might be the first to hope in Christ to the praise of his glory.

In him you also heard the word of truth, the gospel of our salvation and were sealed with the Spirit of promise through faith in him, who is the pledge of our inheritance until at last it becomes our possession to the praise of his glory.

Therefore, since I learned about the faith which exists among you in the Lord Jesus and about your love for all the saints, I have not ceased to give thanks for you and to remember you in my prayers, that the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, may give you the Spirit of wisdom and of revelation in the knowledge of God, the illumination of the eyes of your heart, that you may know how great the hope is that is given you through his call, the abundance of the glory of his inheritance for his saints, and the inestimable greatness of is power for us who believe in the exercise of the power of his strength.

He exercised this [power] upon Christ when he raised him from the dead and placed him at his right hand in the heavenly world over all origins and authorities and powers and dominions and over everything which can be named, not only in this world but also in the world to come; and he placed everything at his feet and made him the head of everything in the Church, for whose filling he fills all in all.

Barth’s Academic Translation

ESV:

1 Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, To the saints who are in Ephesus, and are faithful in Christ Jesus:

2 Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.

3 Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us in Christ with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places,

4 even as he chose us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and blameless before him. In love

5 he predestined us for adoption as sons through Jesus Christ, according to the purpose of his will,

6 to the praise of his glorious grace, with which he has blessed us in the Beloved.

7 In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according to the riches of his grace,

8 which he lavished upon us, in all wisdom and insight

9 making known to us the mystery of his will, according to his purpose, which he set forth in Christ

10 as a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth.

11 In him we have obtained an inheritance, having been predestined according to the purpose of him who works all things according to the counsel of his will,

12 so that we who were the first to hope in Christ might be to the praise of his glory.

13 In him you also, when you heard the word of truth, the gospel of your salvation, and believed in him, were sealed with the promised Holy Spirit,

14 who is the guarantee of our inheritance until we acquire possession of it, to the praise of his glory.

15 For this reason, because I have heard of your faith in the Lord Jesus and your love toward all the saints,

16 I do not cease to give thanks for you, remembering you in my prayers,

17 that the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, may give you the Spirit of wisdom and of revelation in the knowledge of him,

18 having the eyes of your hearts enlightened, that you may know what is the hope to which he has called you, what are the riches of his glorious inheritance in the saints,

19 and what is the immeasurable greatness of his power toward us who believe, according to the working of his great might

20 that he worked in Christ when he raised him from the dead and seated him at his right hand in the heavenly places,

21 far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the one to come.

22 And he put all things under his feet and gave him as head over all things to the church,

23 which is his body, the fullness of him who fills all in all.

Barth:

1 Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God to the saints and believers in Christ Jesus.

2 Grace be with you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.

3 Blessed be God, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us with every spiritual blessing, in heaven, in Christ:

4 In him, he chose us before the creation of the world to be spotless and blameless before him.

5 In love he determined us through Jesus Christ his Son, according to his good pleasure, to exist

6 for the praise of the glory of his grace, which he lavished upon us in the Beloved.

7 In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of sins according to the riches of his grace,

8 which he has generously given us in perfect wisdom and insight:

9 to make known to us the mystery of his will, according to his good pleasure

10 (to accomplish in the fullness of time according to his intention) to gather together everything in Christ, the heavenly and the earthly in him.

11 In him we have also become heirs, having been determined (according to the intention of him who accomplishes everything according to the purpose of his will)

12 to the praise of his glory to be the first to hope in Christ.

13 In him, you also, having heard the word of truth, the message of your salvation and believing in him, were sealed with the Holy Spirit of promise,

14 the downpayment of our inheritance, until it becomes our own possession, to the praise of his glory.

15 Therefore, since I learned about your faith in the Lord Jesus and your love for all the saints,

16 I have not stopped giving thanks for you, remembering you in my prayers –

17 that the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, may give you the Spirit of wisdom and of revelation to know him,

18 the illumination of the eyes of your heart so that you know what the hope is that is given to you through his call, what the abundance of the glory of his inheritance is for his saints,

19 and what the surpassing greatness of his power is for us who believe in the exercise of the power of his strength.

20 He exercised this in Christ when he raised him from the dead and placed him at his right hand in the heavenly world:

21 over all origins and authorities and powers and dominions and over everything which can be named, not only in this world but also in the world to come;

22 and he placed everything at his feet and made him the head of everything in the church,

23 which is his body, the fulfilling of which he fills all in all.

June 9, 2016

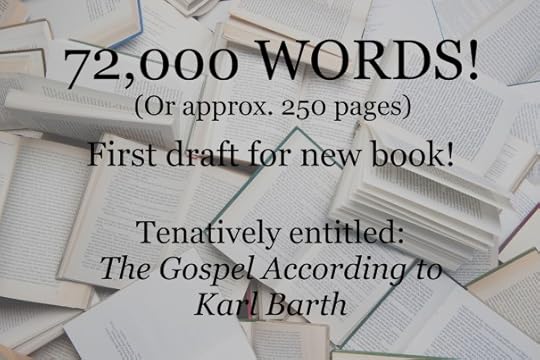

Celebrate With Me! – First Draft Complete (72K Words)

Last night I finished writing the first draft of a new book, which is looking to be my longest and most comprehensive yet! I’ve written over 72,000 words towards what I am tentatively calling The Gospel According to Karl Barth: A Guide Through CD IV.1. I was inspired to attempt this book after writing several articles here which were received quite well, regarding various doctrines from Barth’s CD IV.1 (the doctrine of reconciliation). These were articles on Barth’s doctrine of sin, and faith.

I never thought I would ever attempt something like this, but I gave it a go and thought to myself: even if it doesn’t work out at the very least I’m studying Barth most exhaustively than I’ve done before, and that’s never a bad thing! But I am proud to say that I got through a first draft—72,000 words, or around 250 pages! We’ll just have to wait and see how the editing goes from here, but I am excited to have this first draft complete and a potential book on the horizons!

My next step for the book is to let it rest for a month or two, put it aside and refrain from looking at it for the time being. During this break I’ll be reading as much as I can on Barth to make sure I’m understanding him correctly. Then after the summer I’ll pick the book back up and attempt to work my way through editing it to completion!

I’ll keep you all up to date about how things are going, but until then—cheers!

Like this article? Share it!

June 8, 2016

Karl Barth on the Authorship of Ephesians and Colossians

Biblical scholars are divided over the authorship of Ephesians and Colossians. Unlike other books like Romans or 1 and 2 Corinthians which are undisputedly Pauline, it has been debated whether Ephesians and Colossians (along with 2 Thes., 1&2 Tim., and Titus) are actually Paul’s authentic letters. It was common in Paul’s day to write a letter and put the name of a respected figure on it instead of your own, so the possibility is certainly there that someone else may have written these letters.

Biblical scholars are divided over the authorship of Ephesians and Colossians. Unlike other books like Romans or 1 and 2 Corinthians which are undisputedly Pauline, it has been debated whether Ephesians and Colossians (along with 2 Thes., 1&2 Tim., and Titus) are actually Paul’s authentic letters. It was common in Paul’s day to write a letter and put the name of a respected figure on it instead of your own, so the possibility is certainly there that someone else may have written these letters.

For Ephesians and Colossians especially, the line of argument usually goes like this: Ephesians and Colossians are so unique to Paul’s thought, they lack some of Paul’s other concerns, namely his common emphasis on eschatological expectation, and these letters are so unique in language, that they seem to have been written by another.

There are many arguments for or against this, but for the moment I am not interested in exploring all of them or presenting my own case. I have been reading the PhD thesis paper of Ross Wright, which contains, among an analysis of the work, a translation of Karl Barth’s 1921-1922 lectures given in Göttingen on the book of Ephesians. I was interested in reading Markus Barth, Karl Barth’s son and a well-respected NT scholar in his own right, who’s also written about Ephesians here, when a friend from the Karl Barth Discussion Group on Facebook pointed out this paper. (Thanks John!)

There are many points of interest in these lectures, as Wright has pointed out, especially in regards to the early-Barth and mature-Barth. But today I want to quote Barth’s own (brief) and insightful comments on this debate. Barth affirms the authorship of Ephesians, and Colossians with it, as Pauline, but he ultimately points out that it matters very little to him either way.

Barth presents an internal argument for this, which means he examines the texts and compares them with other undisputed letters to answer the question of authenticity. Essentially, Barth finds no problem with the differences of language and of emphasis from what would be an early-Paul and a late-Paul (if these are authentically Pauline). Just as other great writers (ironically, including Barth himself!) had periods of early and late thought, so Paul may have had this kind of transition. So we cannot maintain that because the letters are different in language and emphasis this automatically discredits them from being Pauline, just as we could not say that the same Barth who wrote Romans ed. 1 could not have also written CD IV.1!

But ultimately Barth comes to this conclusion (bold is mine for emphasis):

“Personally, I would defend the authenticity of Ephesians. But frankly, I do not have any great interest in the question. As far as I am concerned, it could be otherwise. […] Bengel expresses my true opinion about it when he says, ‘Noli quaerere quis scripserit sed quid scriptum est.’ [‘Do not ask, Who wrote it? but, What is written?’] Now that we have dealt with this second unavoidable introductory question, we can happily devote ourselves entirely to ‘quod scriptum est.’ [What is written.] As for the authorship question, it is enough to know that someone, at any rate, wrote Ephesians (why not Paul?), 30 to 60 years after Christ’s death (hardly any later than that, since it is attested by Ignatius, Polycarp, and Justin), someone who understood Paul well and developed the apostle’s ideas with conspicuous loyalty as well as originality.” (P. 6)

Well said!

I’m not sure whether or not this is an insight which Barth maintained throughout his career, but maybe someone who knows for sure would be kind enough to tell me in a comment. But either way, this is a fascinating paper so far. A big thanks goes to Ross Wright for translating these lectures, they are very interesting! (Read them for yourself here.) More articles may come as I continue reading through them, as well as Wright’s analysis of the text.

Like this article? Share it!

May 28, 2016

Kurt Vonnegut in Praise of the Lord’s Prayer

I’ve just begun reading Brian Zahnd’s short autobiographical book Water to Wine: Some of My Story, and I’ve been enjoying it tremendously. I may quote Zahnd in later articles, as it really is a beautiful book. But today I wanted to share with you a fascinating quote he shares from the atheist Kurt Vonnegut, as well as some of my own reflections on the Lord’s Prayer. Enjoy!

I’ve just begun reading Brian Zahnd’s short autobiographical book Water to Wine: Some of My Story, and I’ve been enjoying it tremendously. I may quote Zahnd in later articles, as it really is a beautiful book. But today I wanted to share with you a fascinating quote he shares from the atheist Kurt Vonnegut, as well as some of my own reflections on the Lord’s Prayer. Enjoy!

(Zahnd’s book is still free on Kindle, last time I checked. So go do yourself a favor and download it while it lasts.)

“While Einstein’s theory of relativity may one day put Earth on the intergalactic map, it will always run a distant second to the Lord’s Prayer, whose harnessing of energies in their proper, life-giving direction surpasses even the discovery of fire.” – Kurt Vonnegut 1

What a remarkable statement this is! Kurt seems to have an even higher view of the prayer than even most Christians have.

Brian Zahnd quotes this as part of a chapter on liturgical prayer. I found this chapter incredibly insightful, but most of all I found that it put in words what I’ve begun feeling about prayer for a long time. Prayer in my charismatic background was always a sort of “free for all” style: you never followed a script, as that was just too religious. But at the end of the day, as Zahnd points out, even the most anti-liturgical churches still practice some kind of liturgy.

I have been feeling this discontentment with the ways I have been taught to pray from my boyhood church and from my schooling at Bethel (read my story here). “Free for all” prayer, or unstructured “just talk to God” prayer may be a good idea in theory, but it really isn’t helping much towards the actual purpose of prayer, which is not to beg God for things or to petition Him endlessly with vain repetition; it is to change us, to form us into the image of Jesus Christ. Liturgical prayer was often looked down on in my charismatic experience, but I am coming to see how valuable it actually is for life in Christ. We need to be reminded that it is not our prayers that matter, but Christ who prays for us as our eternal representative, as our intercessor. And we also need to be reminded that we do not have to reinvent the wheel every time we pray, but instead learn to stand on the shoulders of great men and women from church history who have formed brilliant and beautiful prayers for us to pray. For this, liturgy helps.

So I write all this to make a public statement of my intent to pray more liturgically. I have found a few helpful iPhone apps that contain prayers as well as daily reminders to pray. (One app is of the Common Book of Prayer, and the other is an Easter Orthodox prayer app. Isn’t the 21st century great?) But most of all I hope to return simply to praying the Lord’s Prayer more regularly. What if we all could all learn to value the prayer just as much, if not more, than Kurt Vonnegut?

“Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy Name; thy kingdom come; thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.

For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit: now and ever, and until ages of ages. Amen.”

(Greek Orthodox version. And yes, in King James/Shakespearian English, because it’s beautiful that way.)

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Kurt Vonnegut, quoted in: Zahnd, Brian (2016-01-11). Water To Wine: Some of My Story (p. 77). Spello Press. Kindle Edition. ↩May 21, 2016

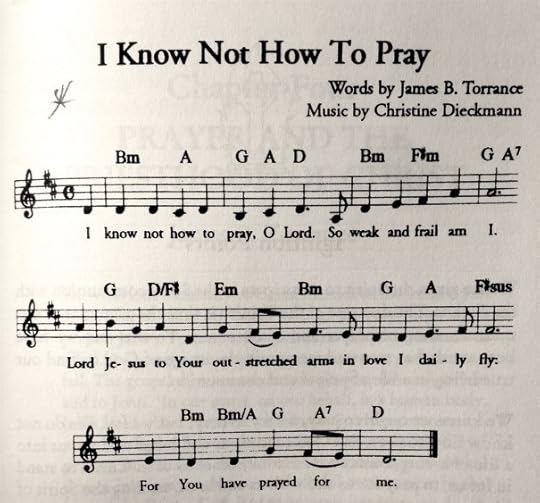

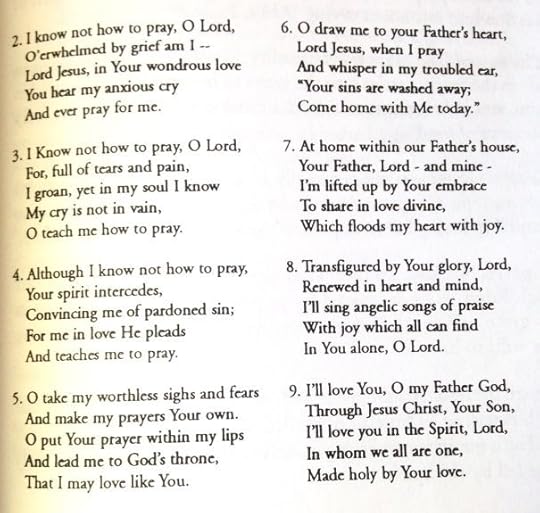

A Hymn by James B Torrance

Last week I read A Passion for Christ written by the three Torrance brothers: Thomas, James, and David. The book is sort of like a “greatest hits” for the brothers, as each chapter presents fragments of their most significant contributions to theology and pastoral ministry. I enjoyed reading the book, and found it to be a very helpful introduction to their theology (especially for anyone who has not read their work).

I’ll eventually write a fuller review. Today however I want to share a Hymn written by James B. Torrance called I Know Not How to Pray.

James has often written about worship, and specifically about a trinitarian understanding of worship in which we partake in the Son’s relationship with the Father in the Spirit. In worship and prayer we do not petition God in our own name or by our own efforts, as if God were some kind of “contract” God and not the covenant God of grace. We pray in the name of Jesus because worship and prayer is participation in the Trinitarian life of God through the Spirit and the Son’s relationship with the Father.

In James’ own words: “Worship is the gift of participating through the Spirit in the incarnate Son’s communion with the Father…” (P. 36) And also, “The doctrine of the Trinity is the grammar of our understanding of prayer and communion.” (P. 60)

As someone who grew up in a methodist/charismatic environment this is revolutionary. When I first read James’ book Worship, Community and the Triune God of Grace several years ago I was amazed at how magnificent God’s grace actually is. (I quote the book here.) God does not leave our relationship with Himself up to us! We are not the authors or perfecters of our faith, of our worship, or of our prayer! We are not called to climb the mountain of prayer to reach God and ask Him to bless us! Jesus Christ has come to us and He has included us in the life of the Trinity. Through the Spirit and in Christ we are taken up into the fellowship of God, we are embraced and we participate in the communion of the Godhead. This is worship: our participation in the life of God—not our striving to please an unhappy God! The act of worship does not rest on our shoulders, nor does the act of prayer or even the entire act of “Christian living’! We participate in the life of Jesus Christ and therefore we say with Paul, “Not I but Christ.” (Gal. 2:20)

James’ hymn is profound because it embodies this theology of worship, which is both a practical doctrine of the Trinity and a theological doctrine of prayer. The doctrine of the Trinity is at once the doctrine of our participation through Christ in the Triune life of God, and therefore the doctrine of prayer must be Trinitarian. There is no separation between who God is in Himself and who God is towards us, and therefore the Trinity becomes one of the most practical and essential doctrines for the Christian. Far from being an abstract idea, the Trinity is the center of our lives in Christ.

So without further ado here’s James’ hymn: I Know Not How to Pray. Enjoy!

(My favorite verse is number seven!)

Like this article? Share it!

May 20, 2016

Read More Books!

I’m on track to read 100 books this year.

I’m on track to read 100 books this year.

So far I’ve read 48 books—in just over five months. The longest book I read was 1,660 pages (Paul and the Faithfulness of God by N.T. Wright), and the shortest 48 pages (Four Quartets by T.S. Elliot). On average I read at least an hour a day, though often more. Usually I’ll read on my way to work or returning home from work, while I’m on the train or bus. But I often read at home too, usually first thing in the morning.

I’m a writer because I’m a reader. I’m a firm believer in the idea that a good writer must be a good reader first and foremost. I have always enjoyed reading, but over the last few years I’ve taken it more seriously and dedicated more time to it; I’ve become a voracious reader.

Last year I read 75 books, this year I challenged myself with 80; although, as I’ve already said, I’m well on my way to 100 books this year.

Today I wanted to share some thoughts on how you can read more books yourself. Maybe you haven’t read a book cover to cover since school, or maybe you’re reading a lot already and just looking to read a bit more, either way here’s a bit of advice on how to read more books!

Why Read?

First of all, why read? In a world of movies, wikipedia, smart phones, and click-bait articles, why pick up a book when everything else seems so much more compelling? Harold Bloom, in his book How to Read and Why?, argues that we read for the simplest of reasons: “To discover and augment the self”. Asking, “Information is endlessly available to us; where shall wisdom be found?”

For some this is true, but not for all. Some read to learn a new business technique, to study an interesting subject, or simply for entertainment. But in the fast-paced world of today, it is sad to see how little reading is taken up. Readers are hard to come by.

But I’m convinced that reading will always be important, perhaps even more so in our fast-paced world. We need the patience a book teaches us, in the midst of quick and easy entertainment. We need to thrill of a quiet afternoon discovering some ancient text, and meeting with the history of thousands who have read and discovered before us. We need the humanity of Shakespeare, the humor of Dickens, the genius of Joyce, the bleakness of Beckett.

We could all read more books. So here’s some tips on how!

Read Harder Books

If you’re over 20 and still reading books like the Hunger Games or the Twilight series (or God forbid, 50 Shades of Grey!), it’s time to step up your book game! Go, as quickly as possible, to your nearest bookstore or library and get yourself a classic: something old, something time-tested. Go pick up Dostoevsky, Melville, Faulkner, Hemingway, Austen, Woolf, Shakespeare, Tolstoy, or anyone else from the classics shelf!

I think a lot of adults are bored with the idea of reading because the only books they think to read are too easy for them. But if you apply yourself, and read something difficult and challenging, you’ll be more engaged in the act of reading, and in turn get more from it.

You don’t have to always read the classics, if, for example, you love a good thriller novel (like the kind my friend Tim Heath writes). But at least give them a shot from time to time!

The Snowball Effect

The more you read the more you’ll want to read. It can be addicting, truly! If you’re too busy, which I know many of us are, then try and commit to just 15 minutes every day. Take this time away from all the time you’ve spent on Facebook today, trust me you have 15 minutes to spare! Set a timer if it helps. If you read for 15 minutes a day, you’ll make it a habit and before long you’ll be reading an hour a day.

The average adult can read about 300 words a minute. For most books this is a page. So in fifteen minutes you should be able to read at least ten pages, which means you’ll be completing a book or more every month (depending on length).

Fifteen minutes is more than possible. Commit to reading just this short amount and you’ll be well on your way to reading more books this year.

Read Kindle Books

Probably half, if not more, of the books I read are on Kindle. I always prefer a “real” book, but by necessity I read eBooks quite often. The best thing about Kindle books is I always have a book on hand, but also the “text-to-speech” function is quite helpful for listening/reading to books quickly.

Always Have a Book With You

This is an important point to reading more. Downloading the Kindle app on your phone is the easiest way! (iBooks works, too. Really another reading app! Though I prefer Kindle.) This way whenever you have a spare minute or two you can spend it reading!

Read Free Books

Reading more doesn’t have to cost you a cent! There are millions of great books you can read in the public domain, including most classic books of literature written before this century. There are several great places to look for free books including Gutenberg, Amazon, Adelaide, and Openculture. And don’t miss out on all my free books, too! Or sign up to my Readers Group and get a free book sent to your inbox every month!

Listen to Audio Books

I don’t read audio books very often, but sometimes, especially with fiction. I like to read along while I am listening to the audio book, especially if it’s a very well done performance. There are two great programs for this: Audible and LibriVox.

Audible has a great deal, you can get two free audio books (high quality ones) just for signing up for a free trial. I downloaded the 24 hour Ulysses audio book for this (a great narration of the book), then I cancelled my membership the following day. That’s a $100 audio book for nothing.

LibriVox is a free alternative. Volunteers read books and upload them up for anyone to download. They aren’t always very professional sounding, but LibriVox is a nice alternative for the budget-conscious.

Join Goodreads

Goodreads is the Facebook for books. It’s a social media platform based entirely around what your reading and what your friends are reading. I’m on it, and I use it often. The best part is how it helps you keep on track towards reading goals. You feel the gratification of checking off another book, and that can help motivate you to read more.

Stop Reading Articles

Quit giving into the click-bait, time wasting vortex; stop reading pointless articles. It’s ironic that I would write this here, in an article, but I’ll be honest with you: you don’t have to read my articles. I’d much rather you read one of my books (three of which are completely free), or someone else’s for that matter. (I have a list of recommended reading here and my favorites from 2015 here.)

95% of online articles that get shared are a complete waste of time. I hope my articles offer genuine content, but if they don’t do anything for you, don’t read them. Pick up a book, instead. You’ll be better off for it.

I rarely read articles online. The only two exceptions being if I know the author, or if I’m doing research.

This rule cuts out all Buzzfeed, bait-click websites making money by wasting your time. Your life won’t end if you never click on the article of “the twenties cutest puppies doing funny things”, I promise.

Just say no to click-bait!

Wrap-up

So there yo have it. Some simple advice that may help you read more books this year. So put down your phone, shut off your laptop, pick up that dusky book, and happy reading!

Like this article? Share it!

May 10, 2016

Happy 130th Birthday, Karl Barth!

Karl Barth was born 130 years ago today. It’s no secret that I greatly admire the theologian, so today I wanted to celebrate him by sharing some of my favorite quotes. But first, I’ll say a bit about why I admire Karl Barth as much as I do.

Karl Barth was born 130 years ago today. It’s no secret that I greatly admire the theologian, so today I wanted to celebrate him by sharing some of my favorite quotes. But first, I’ll say a bit about why I admire Karl Barth as much as I do.

Karl Barth was a theologian of joy. He famously said, “The theologian who labors without joy is not a theologian at all.” Joy is essential to the work of theology, if sadly today few have learned this lesson from Barth. When I read Barth one of the most striking things about his work is how full of life and joy it is. He does not write as a man without hope, he writes of the living God, the God who is present with us, who is for mankind, the God of Jesus Christ. And because of all this, Barth writes with the most profound joy.

Karl Barth was a theologian of Jesus Christ. Central to his theology is Jesus. It’s a aptly applied joke about Barth to say: “The answer is Jesus, what’s the question?” Reading the Church Dogmatics especially highlights this christological focus. As one of his students, Thomas F. Torrance, puts it, “There is no God behind the back of Jesus Christ.” This is central for Barth, and one of the aspects of his theology that I have learned from the most.

Karl Barth was a genius. This is obvious to anyone who reads even the smallest of his works. The stunning brilliance and creativity and discipline with which he was able to produce such an astonishing body of work goes without saying for anyone who’s studied Barth. It’s what makes him so difficult at times, but it’s also what makes him so profoundly simple.

I personally owe much to Karl Barth, as he’s helped shape my own thinking about God tremendously, but so does the church today. He has moved theology forward in tremendous lengths, and anyone who engages with theology in the future must also engage with Karl Barth.

But to all this talk of appreciation and of his greatness, Karl Barth would say, “Nein!” He was above all a humble theologian. He was not interested in calling himself great, though history will remember him this way. And this final point is why I respect him even more, he was humble, always realizing that to do theology meant above all else worshiping God and giving Him glory. His work always has this doxological characteristic to it, it is worship. As Jürgen Moltmann once said about it, when he was asked why Barth would write 9,000 pages in the Church Dogmatics, he responded that the whole Dogmatics could be summarized on half a page, yet, “The rest is worship.” 1

Quotes

It’s hard to say what my favorite quotes from Barth are because there are so many, Barth was incredibly quotable. But here are just some of my favorites that I could find, and they offer a good insight into Barth in celebration of his birth. So happy birthday, Karl Barth!

“In the fourth place, the God of the Gospel is no lonely God, self-sufficient and self-contained. He is no “absolute” God (in the original sense of absolute, i.e., being detached from everything that is not himself). To be sure, he has no equal beside himself, since and equal would no doubt limit, influence, and determine him. On the other hand, he is not imprisoned by his own majesty, as though he were bound to be no more than the personal (or impersonal) “wholly other.” […] Just as his oneness consists in the unity of his life as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, so in relation to the reality distinct from him he is free de jure and de facto to be the God of man. He exists neither next to man nor merely above him, but rather with him, by him, and most important of all, for him. He is man’s God not only as Lord but also as father, brother, friend; and this relationship implies neither a diminution nor in any way a denial, but, instead, a confirmation and display of his divine essence itself.” (Evangelical Theology, P. 10-11)

“A quite specific astonishment stands at the beginning of every theological perception, inquiry, and thought, in fact at the root of every theological word. This astonishment is indispensable if theology is to exist and be perpetually renewed as a modest, free, critical, and happy science. If such astonishment is lacking, the whole enterprise of even the best theology would canker at the roots. On the other hand, as long as even a poor theologian is capable of astonishment, he is not lost to the fulfillment of his task. He remains serviceable as long as the possibility is left open that astonishment may seize him like an armed man.” (Evangelical Theology, P. 64)

“Whoever begins to concern himself with theology also begins to concern himself from first to last with wonders.” (Evangelical Theology, P. 65)

“The content of God’s Word is his free, undeserved Yes to the whole human race, in spite of all human unreasonableness and corruption.” (Evangelical Theology, P. 79)

“Theological work can be done only in the indissoluble unity of prayer and study. Prayer without study would be empty. Study without prayer would be blind.” (Evangelical Theology, P. 171)

“Without love, theological work would be miserable polemics and a waste of words.” (Evangelical Theology, P. 197)

“At the beginning of all theological perception, research, and thought—and also of every theological statement—stands a quite specific amazement. Its lack in even the best theologian will threaten the heart of the entire enterprise, while even bad theologians are not a lost cause in their service and their duty, as long as they are still capable of amazement.” (Insights, P. 3)

“The doctrine of election is the sum of the gospel because of all words that can be said or heard it is the best: that God elects man; that God is for man too the one who loves in freedom.” (Church Dogmatics II.2, P. 3)

“God’s eternal will is the election of Jesus Christ.” (Church Dogmatics II.2, P. 146)

“‘God with us’ is the centre of the Christian message—and always in such a way that it is primarily a statement about God and only then and for that reason a statement about us men.” (Church Dogmatics IV.1, P. 5)

“To say atonement is to say Jesus Christ.” (Church Dogmatics IV.1, P.158)

“I don’t teach universal reconciliation but I don’t not-teach it.”

“[Man] may let go of God, but God does not let go of him.” (Church Dogmatics II.2)

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

I’m paraphrasing from this video. ↩