Stephen D. Morrison's Blog, page 13

March 12, 2016

The Bible is Not a Guide Book

This week I took the time to read Peter Enns fantastic little book, The Bible Tells Me So. It has been a book on my reading list for some time, but it was recently discounted to $1.99, so I had to snatch it up. (As of my writing this, the book is still on sale. I highly recommend it!)

This week I took the time to read Peter Enns fantastic little book, The Bible Tells Me So. It has been a book on my reading list for some time, but it was recently discounted to $1.99, so I had to snatch it up. (As of my writing this, the book is still on sale. I highly recommend it!)

Today I wanted to discuss one of the main ideas of this book, one that Peter Enns kept returning to time and time again: the bible is not a Christian guide book, it is a story—it is the story of God’s people.

The B.I.B.L.E.

I’ve often heard this cheesy Christian phrase, that the bible is: “Basic Instructions Before Leaving Earth”.

I couldn’t have come up with a more inaccurate definition of the bible even if I tried. There are several issues here. First of all, the bible never says its a guide book. It doesn’t present a step-by-step solution to all your problems. And second, who says we’re leaving earth anytime soon? Won’t the Kingdom of Heaven be established here on this earth? It will be made new, but we can’t be too quick at leaving it behind. 1

And let’s be honest. The bible isn’t really a very good guide book, if it is one at all. It contradicts itself quite often, it tells a lopsided version of history, and sometimes even promotes murder, genocide, or slavery.

This phrase is an attempt to try and force a misbehaving bible to behave.

But what do we do when the bible just doesn’t behave like we want it to? When we’re honest with ourselves, it’s hard to ignore this fact. The bible doesn’t behave like a rule book, or even like a Christian guide book. It simply does not contain all the answers to life. The bible will not tell you who you should marry, if you should take that job or not, what city you should live in, if the carpet on your new home should be grey or beige, what investments you should make in the stock market, or what you should do with your life! As much as we pretend the bible can do all these things, it simply cannot. It is not the end all answer book for Christian living. We are living an illusion if we think it is.

But why do we continue to speak of the bible in this way? As if the bible actually contains our step-by-step guide for our lives?

In some ways, we probably do this out of fear. We don’t want to be uncomfortable in our faith. We want easy answers, simple truths, and incontestable voices of reason. And most of all, we certainly don’t want to trust in the Holy Spirit! Please God anything but that! So instead of trusting the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Truth, to be our guide, we would much rather have a book answer all our burning questions. Because God forbid we learn how to think for ourselves or learn to lean on the wisdom of the Spirit in us!

We have tried to make God the Father, Son, and Holy Bible! But what a horrific disgrace to the God who loves us and has given us the gift of His Spirit. We have tried to replace our brains and the Holy Spirit in us with a non-thinking bible of simple facts and easy guides. But it simply will not behave as we would hoped it would.

Biblical realism

Rather than trying to fit the bible into what we think it should be, we should let the bible be what it actually is. The bible is a story. It is the story of the people of God, and the people of God are never without their flaws. Yes, the bible is inspiring, it is moving, and it is certainly inspired. However, the bible sometimes is really unsettling (like when God commanded the genocide of the Canaanites), or just plan difficult to reconcile with our modern world (like believing that a fruit is the cause of all our problems). But when we let the bible be what it is, we will learn far more from it than we ever imagined.

When you read the Bible on its own terms, you discover that it doesn’t behave itself like a holy rulebook should. It is definitely inspiring and uplifting— it wouldn’t have the shelf life it does otherwise. But just as often it’s a challenging book that leaves you with more questions than answers. 2

So here’s my not so radical thought: What if the Bible is just fine the way it is? What if it doesn’t need to be protected from itself? What if it doesn’t need to be bathed and perfumed before going out in public? 3

We should adopt this biblical realism in our approach to scriptures. We can certainly see that this book is inspired and God breathed, but that doesn’t mean we also can’t say that it has its difficulties. It is a historical book and we can’t pretend it isn’t by treating it otherwise. It tells of a people from a long time ago, and we have to let it be what it is without trying to tame it or force it to meet our expectations.

What if the Bible is just fine?

The bible is a challenging book, and the writers of the bible didn’t have all the answer. They, like you and me, are on a journey. This journey is just as much our story as it is God’s story, but this does not mean it is a perfectly accurate story. Peter Enns has a great little chapter heading called, “God Lets His Children Tell the Story”. And this is exactly what the bible is about, especially its narrative. God has let his children tell the story of their journey with Him, and I think it’s because God knows that sometimes our journey can be more powerful than even the most accurate of facts (historical or otherwise).

Therefore, the bible has gone through this filter, the filter of God’s people telling the story. Accordingly, their culture, history, and personal experiences all come into view.

Is God always exactly as He appears to be in the Old Testament? Did God actually command genocide and murder? Not necessarily. Sometimes the bible has more to tell us about what the Israelites believed about God than what God is actually like. In Enns’ words:

These ancient writers had an adequate understanding of God for them in their time, but not for all time— and if we take that to heart, we will actually be in a better position to respect these ancient voices and see what they have to say rather than whitewashing the details and making up “explanations” to ease our stress. And for Christians, the gospel has always been the lens through which Israel’s stories are read— which means, for Christians, Jesus, not the Bible, has the final word. 4

The scriptures are like a good period piece. They sometimes say more about the people involved than the accuracy of their beliefs. The Israelites had a good understanding of God for their time period, and it was actually fairly progressive with their insistence upon monotheism. But their understanding of God is not a universal, be-all end-all truth about what God is like.

Only Jesus is the universal, be-all, end-all image of God.

Jesus is the image of the invisible God. Which implies that before Jesus, God was invisible to human beings. So even though the Old Testament claims at times to speak of God, it speaks only in shadows about God. The only concrete knowledge of God is found in Jesus.

The ultimate context of the scriptures is Jesus Christ. Christ is the controlling center of the scriptures. This idea was echoed in another recent article on Thomas F Torrance, where he writes: “Strictly speaking, Christ himself is the scope of the Scriptures, so that it is only through focusing constantly upon him, dwelling in his Word and assimilating his Mind, that the interpreter can discern the real meaning of the Scriptures.”

Jesus Christ alone is the scope of the scriptures, the controlling center of our thought about what God is like. Which means the bible is not this center. The center of the Christian faith is not the bible, it’s Jesus. Jesus alone is the revelation of God, the bible gives witness to this revelation, but in itself it is not this revelation. 5

So what then?

So what is the conclusion we should make from this? If we are to take up a realist relationship with the scriptures, emphasizing the person of Christ as our controlling center of thinking about God, then how do we now relate to the bible itself? In Enns’ own words:

This is the Bible we have, the Bible where God meets us. Not a book kept at a safe distance from the human drama. Not a fragile Bible that has to be handled with care lest it crumble in our hands. Not a book that has to be defended 24/ 7 to make sure our faith doesn’t dissolve. 6

The bible is where God meets us. It is where we read the story of God and of His people. It isn’t always perfect, or accurate, and often it can be difficult and challenging, but it is what we have. It is where God meets us. We don’t have to defend it, or wage war with it, or look to it and it alone as our source of guidance. We should examine the bible carefully, with reverence and appreciation, but also with realism. We cannot continue to place unrealistic expectations upon the bible, supposing it to be something it isn’t.

And when we do this, when we take the bible realistically, the bible will challenge us. It may not always comfort us, and it may very well unsettle us from time to time—but that’s okay. Christianity never came with the promise of simple answers or a step-by-step guide to life. It has promised to change our lives, to radically reshape our worldview, and most importantly, to bring us into relationship with God Himself. But none of these things are normal. So we have to be willing to let the bible bring a little discomfort from time to time, as we are faced with challenging stories about God and mankind. In these pages we hear the echo of our personal story, and on these pages through all the difficulties, we still met Jesus Christ the Son of the Father, our savior, our brother.

Why else would the Holy Spirit be called the Comforter, if we shouldn’t expect to be uncomfortable from time to time? Even, and especially, in the book about God’s interaction with sinful man?

The bible is not a guidebook full of easy answers. The bible recounts the story of God and human beings—fallible, sinful human beings. And as such, the bible is an amazing book. One we can appreciate even more when it’s understood correctly.

(I highly recommend Peter Enns book to you, and I think you should take advantage of this great deal before its gone.)

And on an unrelated note: my favorite book I’ve written, so far, We Belong: Trinitarian Good News, is available now for a discounted price: $4.99 for an eBook or $12.99 for a paperback copy. Get yours here.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

More on this from my (free!) book 10 Reasons Why the Rapture Must be Left Behind ↩Enns, Peter (2014-09-09). The Bible Tells Me So: Why Defending Scripture Has Made Us Unable to Read It (p. 4). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. ↩Ibid. p. 9. Bold mine. ↩Ibid. p. 65. ↩This is the purpose of my article The Bible is Inadequate (& That’s Why It’s True) ↩Ibid. p. 232 ↩March 5, 2016

Karl Barth’s Revolutionary Doctrine of Sin

I’ve been recently going through volume IV.1 of Karl Barth’s magnificent Church Dogmatics, in which Barth outlines the doctrine of reconciliation. I’ve read parts of this volume before, specifically §57-59, and they remain some of my favorite texts from Barth. This volume is an incredibly beautiful work of theology. Here Barth masterfully outlines the good news of Jesus Christ and of what He has done for us in reconciling us back to the Father.

(A brief summary in Barth’s own words: “To say atonement is to say Jesus Christ.” … “He took our place as Judge. He took our place as the judged. He was judged in our place. And He acted justly in our place.” 1)

But today I want to examine sections from §60, which includes what I consider Barth’s “revolutionary” doctrine of sin.

Karl Barth’s Revolutionary Doctrine of Sin (IV.1, §60)

To begin, there are two particular reasons why I feel this doctrine so important, so “revolutionary”, especially for today’s evangelical church, and for how the gospel is often preached.

First of all, the placement of this doctrine is critical. As Barth notes, he has intentionally placed this doctrine of sin after the doctrine Jesus Christ the reconciler and not before it. He does not, as it is commonly done in evangelical theology, place sin before Christ. This is profoundly important. For Barth, the context and meaning of Jesus’ coming is not sin, but the eternal will of God for man. Jesus was an event of self-determination, not the side-effect of sin and death.

And second of all, following this structure, Barth has made certain that sin is not defined in a vacuum, but only as it is found in relation to Jesus Christ, the victor over sin. It is therefore only in Christ’s defeat of sin that Barth claims we can know sin at all. “The reality of sin cannot be known or described except in relation to the One who has vanquished it.” 2

So this essentially means that the way we understand sin cannot be an abstract moral definition of it, or even worse, what we judge ourselves to be what is right or wrong. Because this is in no way sin as God has defined it. Following the way in which we know God, only through Jesus Christ, the way we know sin is the same. Was can only come to form a doctrine of sin in the light of Jesus Christ and particularly in the light of our reconciliation in Him. Only in the context of sin as it is defeated can we identify what it is. As Barth writes, “…we maintain the simple thesis that only when we know Jesus Christ do we really know that man is the man of sin, and what sin is and what it means for man…” 3

In § 60.2, under the heading “The Pride of Man”, Barth follows the same outline he has already presented in other sections of this volume, but reverses them. In examining what Jesus Christ has done for us, we understand the sin Christ has conquered.

Barth begins first by asserting that the chief sin of all is “unbelief”. Saying, “It is true enough that unbelief is the sin, the original form and source of all sins, and in the last analysis the only sin because it is the sin which produces and embraces all other sins.” 4

But unbelief in what? In God? But which God? Surely not just any abstract God? Barth continues by narrowing down the exact God who man has disbelieved. He writes, “Man’s sin is unbelief in the God who was ‘in Christ reconciling the world to himself,’ who in Him elected and loved man from all eternity, who in Him created him, whose word to man from and to all eternity was and will be Jesus Christ… In Him God Himself is revealed as the One who commands in goodness…” 5

The sin of mankind is unbelief in the God revealed in Jesus Christ, the God who is for mankind, the God who has from all eternity determined Himself to love us and elect us, to be our God. In short, our sin is unbelief in the goodness of God as revealed in Christ. We have failed to see that this God is for us, and not against us!—loves us and embraces us and is good to us. And Barth says that this unbelief is the chief sin and the root of all other sin.

It reminds me a lot about what C. Baxter Kruger has said about our need for assurance. We must know that we are loved by God and know it with certainty. We must believe in the goodness of God and bask in it. Only when we know that we are loved from before all time by God, can we learn to be free from sin and shame and guilt. When we see ourselves embraced by the goodness of God, we leave sin behind.

But Barth continues, as I mentioned, to outline the counter-action of man that is healed in Christ’s redemption. He does this in four points.

First, that the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us. This is the humility of God, the God who in freedom became man for our sakes. Sin, in this light, is that we as a human race desire to be Gods. God became a man to cure us of this sin. He humbled Himself and became one with us to destroy our prideful illusions of ever becoming God.

Second, that Jesus is our Lord as a servant. Jesus came not to be served but to serve, and this reveals the nature of God as the Lord. He is not Lord as we imagine, but Lord as the servant. He humbles Himself and becomes the servant of sinful man. Mankind, on the other hand, wants to be Lord over all, to pridefully command all things. Yet Jesus comes to heal our evil fixation with this illusionary Lordship, by revealing that true Lordship is servanthood.

Third, that Jesus is the Judge judged in our place. He alone is the righteous Judge of man, and He has, as this judge, suffered and died in the judgement we deserved. He is the Judge who steps down and dies the judgement He proclaims in the place of the unjust. Yet we, in our prideful humanity, desire to be our own judge. We desire to be the masters of our own lives and to judge for ourselves what is right and wrong. Yet Jesus reveals the high price of the Judge, and unveils the truth that only God’s judgement is truly righteous.

Fourth, Jesus dies helpless and in complete abandonment on the cross. He was crucified and buried in full trust that despite His helplessness, God, His dear Father, would come to help. Humanity, in our pride, attempts self-help, self-salvation. We try to be our own hero. But God in Christ shows that it is only when we are helpless and fully abandoned to His salvation, that we are free from our illusion, and He saves us. 6

Implications

The implications to this doctrine are incredible and essential for the evangelical church today. The gospel is often preached in this way: First, that we are sinners, and only then that Christ came to save us. But here Barth has placed Jesus Christ, yet again, at the center of our Christianity. We do not preach Jesus Christ with sin tacked onto the end of our sermon, as if Jesus is a footnote to our salvation! I know from personal experience that there are camps of Christian theology that believe we must preach sin 90% of the time, and only long after everyone is condemned and feeling bad about themselves do we preach the good news of what Jesus has done. Barth’s doctrine of sin flips this whole enterprise on it’s head. We can only know sin in the light of the Conquerer of sin. Only in the light of Jesus’ redemption can we truly understand the depravity of our existence. And in this way, even in preaching sin we preach the grace of God for all mankind, because we cannot preach sin apart from the conquerer of sin, Jesus Christ. Sin is never without this grace!

Whenever our efforts are on anything other than the gospel, we are wasting our time. If we focus more on morality, on self-improvement, on how bad people we are, or on any other topic except for Christ and Him crucified, we are not preaching the Gospel. Sin, legalism, and morality are not the message of the church. Only Jesus Christ, His life and work, are we to proclaim. And when we do, we truly preach the gospel. And perhaps, if we get our focus once again on Jesus Christ and Him crucified, we might become once again relevant to society. Because we will no longer be preaching religion or do-goodery, we will preach grace. And the world is starving for real grace.

This was also the main point of the “On Preaching the Gospel” chapter in my book, We Belong. As I wrote there, “The Gospel is an announcement, not a threat!” My hope is that the church today would come to recognize this, and following Barth’s example, learn once again to preach sin in the light of Jesus Christ. And only then can we echo Paul’s mantra, “I resolved to know nothing while I was with you except Jesus Christ and Him crucified.” (1 Cor. 2:2)

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Karl Barth Church Dogmatics IV.1, P. 158 and 273 respectively, Hendrickson Publishers, 2010 ↩ Ibid. P. 144 ↩Ibid. P. 389 ↩Ibid. 414. ↩Ibid. P. 415 ↩This section follows the outline of Barth from pages 418-478 ↩February 25, 2016

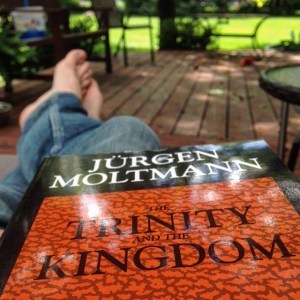

The Weakness of God

In my book, Where Was God? (which you can get right now for free), I explore the idea of God’s impassability (His inability to suffer) in the face of human suffering. If God has suffered and died on the cross, why do we say that God cannot suffer? The answer, which I discovered in the theology of Jürgen Moltmann, was simple. God can suffer, and in fact He does suffer. God is not impassable in the sense that He is unaffected or unmoved by the suffering of mankind. But quite radically, we must say that since the crucified Christ is the “image of the invisible God” (Col. 1:15), and that this is what God is like, then God can and does suffer with mankind. And furthermore, as Moltmann concluded, we must place suffer and death itself in the very Triune life of God. God intimately knows suffering and death in Himself, He experiences our suffering when we suffer and He joins us in our death through Jesus’ death.

In my book, Where Was God? (which you can get right now for free), I explore the idea of God’s impassability (His inability to suffer) in the face of human suffering. If God has suffered and died on the cross, why do we say that God cannot suffer? The answer, which I discovered in the theology of Jürgen Moltmann, was simple. God can suffer, and in fact He does suffer. God is not impassable in the sense that He is unaffected or unmoved by the suffering of mankind. But quite radically, we must say that since the crucified Christ is the “image of the invisible God” (Col. 1:15), and that this is what God is like, then God can and does suffer with mankind. And furthermore, as Moltmann concluded, we must place suffer and death itself in the very Triune life of God. God intimately knows suffering and death in Himself, He experiences our suffering when we suffer and He joins us in our death through Jesus’ death.

Learning this revolutionized my understanding of God and the way I think about the gospel. Since Jesus has truly suffered as a man, God deeply understands mankind. We do not find an abstract God void of emotion in the gospel, we find a personal, relatable, intimate God who suffers with mankind. What a beautiful picture this is!

But as I read Jürgen Moltmann’s latest book, The Living God and the Fullness of Life (which I recommend!), I was once again challenged in my understanding of God. Traditionally God is called the “Almighty”, and the scriptures affirm this. But what does that actually mean?

Is God Almighty?

For most, this is an abstract term about God’s ultimate dominance. As Moltmann writes, “If we see the Deity as the all-determining summit of universal monarchy, then it must be ‘all-determining reality.'” 1 The logical conclusion we make about an abstractly “Almighty” God is that such a God must determine all history, and in fact all existence.

But is this what is means to be Almighty? Is God the determining cause of everything that happens in creation?

On one hand this is an appealing claim to us, because we tend to relate such absolute power with freedom. We believe we are free when we can accomplish something or determine the outcome of an event. So the ultimate, highest understanding of this must be a completely free God who determines all things. But is that really freedom in itself? Is an Almighty God that must be all-determining really free?

According to Moltmann, no. He writes, “Is the Almighty free? No, for God has to be ‘the all-determining reality.’ For God there is no alternative to rule over the world. In this way God is tied down to this almighty role. Is the Almighty a subject? Yes, but a fixed subject. Is the Almighty a God in relationship? Yes, but only in a single relationship of determining everything. Has the Almighty power over Godself? No, God can do nothing other than rule over everything. So, in fact, the Almighty is powerless and a prisoner of the universe.” 2

The Almighty is a prisoner, because the Almighty is responsible for everything. Which means the Almighty is accused of the theodicy question. Which makes sense. If God is all determining, why doesn’t God end suffering and death? But in this line of thinking an “almighty” God, as the all-determining God, is nothing short of a monster-God, because such a God causes and wills all suffering, corruption, injustice, and death in the world. But is this what God is like? And is such a God really free? No. Because an all-determining God cannot “withdraw into Godself”, as Moltmann puts it. Such a God cannot choose not to be “Almighty”.

So how then should we re-understand the “almighty-ness” of God?

To be Almighty Means the Freedom to be Weak

A God who is Almighty, in the Christian sense, cannot be an “all-determining” God. Because such a God is not free to withdraw, and to have power over Godself. Such a God is a slave to the reality being determined, and therefore unfree to choose not to determine that reality.

So what then? Am I saying that God is not almighty?

Certainly not. The “Almighty” label for God is found all throughout the scriptures, especially in the Old Testament. So instead of dropping that title, what I’m proposing is we rethink what God as the Almighty actually means.

An Almighty God is not an “all-determining” God. Rather, God is free in Godself. God is free to withdraw from history, to determine Godself. In other worlds, God is not required in Gods almighty-ness to determine all things. This is an act of self-limitation. God certainly could determine all things, but since God is free God does not have to. As Moltmann continues to say, “The limitation of God’s unending power is an act of God’s power over Godself. Only God can limit God.” 3 The Almighty God is free to limit Godself. This is what it means to be Almighty, in the Christian sense: the limitless God is free to be self-limited.

And God has chosen to do exactly that.

God has chosen not to be counted among the “mighty”, but among the weak. God has chosen solidarity with the broken, the outcasts, the lost, and the forgotten. God has chosen to be weak with the weak, poor with the poor, and to suffer with those who suffer. This is apparent especially in the life of Jesus, who commonly ate with sinners, and fellowshipped with the so-called outsiders of society. It often was a mark against Him according to the religious rulers of the day, and still is today in stark contrast against the way we tend to understand God. But if this is who Jesus is, we must say this is what God is like, because it is what God has revealed about Himself.

The God of Jesus Christ is the God of outcasts, the God of the weak, of the helpless, and of the needy.

God is free and in freedom God has decided to limit Godself. This is how God is “Almighty”. It is not because God is all-determinating, but because God in freedom has chosen weakness, helplessness, suffering, and even death for Himself that God is Almighty.

As Moltmann writes, “God is not on the side of the mighty as ‘the Almighty’—God is on the side of the weak, as the liberator who is in solidarity with them. The living God chooses the weak in the world and rejects the mighty.” 4

This is the almighty-weakness of God! Not that God is lacking, but that God in His majesty and love has chosen to be our God, to be the God of those who suffer, who die, who weep, and who are weak. He radically chooses solidarity with mankind, and rejects even His own might for our sakes.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

The Living God and the Fullness of Life by Jürgen Motlmann, P. 43 ↩ibid, P. 44 ↩ibid P.45 ↩ibid p. 47 ↩February 13, 2016

The Bible is Inadequate (& That’s Why It’s True)

The bible is a tremendous gift to mankind. It is true, it is right, and most of all it is a witness to the Word of God. But it is not perfect. And in fact, the whole “true”-ness of the scriptures depends upon its inadequacy.

The bible is a tremendous gift to mankind. It is true, it is right, and most of all it is a witness to the Word of God. But it is not perfect. And in fact, the whole “true”-ness of the scriptures depends upon its inadequacy.

It is a hotly debated subject to say the least, the nature of the scriptures. But it’s an essential one. So you have to understand something before we begin. I do value the bible highly, and furthermore, I feel I value the bible even more than ever now that I understand it in this way. The bible has a special place in my heart, and has always been an important part of my journey as a believer. But in recent years I’ve begun to question the idea that it is, in and of itself, absolutely perfect. I still believe that it is true, and that it is filled with life and meaning and beauty—but I no longer see every single letter of the bible to be perfect. And so, let me tell you why I believe that’s a good thing.

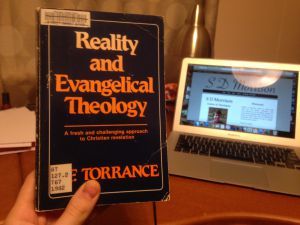

Scripture as Witness

First, let me quote the man who summed up so well what I’ve been feeling about the bible for some time now: Thomas F. Torrance. I already listed several quotes from Torrance in my last article, but today I will expound on a few of them:

“In a realist theology this will mean that we must distinguish no less sharply between dogmatic formulations of the truth and the truth itself, in the recognition that even when we have done all that it is our duty to do in relating them rightly (i.e., in an “orthodox” way) to the truth, they nevertheless fall far short of what they should be, and are inadequate. Indeed, it must be said that their inadequacy in this way is an essential part of their truth, in pointing away from themselves to the truth they serve, as it is an essential element in their objectivity in being grounded beyond themselves on reality that is independent of them.” 1

And also this one:

“That is to say, biblical statements are to be treated not as containing or embodying the Truth of God in themselves, but as pointing, under the leading of the Spirit of Truth, to Jesus Christ himself who is the Truth. We have to recognize the fact, therefore, that the Scriptures indicate much more than can be expressed, and that there is much more to their truth than can be reduced to words.” 2

Thomas Torrance is not the always easiest to understand, so let me unpack a little about of what I think he means here.

First of all, he is writing about the nature of scripture in relation to objective truth (Jesus Christ). Jesus Christ is truth. He is the Word of God. In other words, Jesus is God saying what He has to say about Himself. He is the objective center to which the bible points. All that we say about God should be said in the light of Jesus, since no knowledge of God is possible “behind the back” of Christ. The question then is, how do the scriptures relate to Jesus? How does a witness to the truth relate to the truth itself?

The scriptures themselves are not the Word of God. John 1 clearly ascribes the Word of God to Jesus Christ, and Jesus Christ alone. Although, following Barth, it is important to see how the scriptures can become the Word of God, when breathed upon and illuminated by the Spirit of Truth. However, this does not make the bible itself perfect, that is, infallible or inerrant. Instead, the bible is a witness to the truth, and only becomes the truth itself when the truth illuminates it and speaks through it. With Barth 3, Torrance is affirming that the scriptures accurately give witness to the Revelation of God, but that in themselves they do not contain the perfect, infallible truth. That is, they are not perfect in themselves, but they are in what they give witness. They become perfect as God speaks through them.

Jesus is the objective truth of the scriptures. The scriptures speak of Jesus in human words, and human words will always be inadequate. They are inadequate words in relation to their object. Yet it’s exactly this fact that makes them true. As Torrance said above: “…their inadequacy in this way is an essential part of their truth, in pointing away from themselves to the truth they serve, as it is an essential element in their objectivity in being grounded beyond themselves on reality that is independent of them.”

The bible points beyond itself. It is inadequate because its center is not in itself, but outside itself. It is also true for this same reason. Inadequacy is proof that the scriptures are true and give accurate witness to the Word of God. Because the scriptures point beyond themselves to the “truth they serve”. The objective truth is not found in the scriptures, but in the truth the scriptures give witness to. The truth of scriptures is above the scriptures themselves. They must be inadequate, or else they might replace the truth which they point to: the Word of God, Jesus Christ.

What this means

What does this mean for how we read the bible today?

It means, firstly, that we can trust the bible even more. More, not because we trust in the bible itself, but because we trust in the truth to which the bible points. We trust in the Holy Spirit’s leading us into all truth, giving witness to Christ, through the scriptures. Our trust in the bible is not in the bible itself, and therefore it is not in the endless history and criticisms which such trust ultimately involves, but instead it is in the God of the bible, in the Spirit that leads to truth. Our trust is in God, not a book. Though this book is God’s witness to Himself. Truth about God is found not in the bible, but through the bible in the Spirit of Truth witnessing to Christ. And only when we see this can we fully trust the bible.

This also means, secondly, that we can no longer be “literalists” in our reading. As I quoted from Torrance here, fundamentalism tends to elevates the bible above the truth they point to. In other words, the bible gets placed above God! We have become enslaved to a literalist word-fight, with proof-texts abounding, and only a proper understanding of the bible as witness can set us free. The bible is not a set of ready-made truths. The truth of scripture is found outside the scriptures in what they point to.

Thirdly, this means in practice that we no longer look to the bible for the bible’s sake, but through the bible for Christ’s sake. Thomas Torrance writes that, “The Holy Scriptures are the spectacles through which we are brought to know the true God…” And also that, “Christ Himself is the scope of the scriptures.” 4 We read the bible as a pair of glass through which we see the truth of God’s Word to mankind.

Far from devaluing the scriptures, this re-understanding places the bible into a context it belongs: as a witness to the objective truth of God’s Word. Out of this context the scriptures become an unhealthy obsession, fixating on every jot and tittle we find, instead of looking beyond them to the face of Jesus.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Thomas F. Torrance, Reality and Evangelical Theology, John Knox Press, 1982, P. 50-1 ↩ibid, P. 119 ↩A great article on Karl Barth’s understanding of the scriptures and error, can be found here (by Postbartian) ↩ibid, P. 64 and 107, respectively. ↩February 7, 2016

Thomas F. Torrance on the Bible (11 Quotes)

A few weeks ago I finished reading Thomas Torrance’s book Reality and Evangelical Theology. In this book, renowned theologian Thomas Torrance deals with an important issue, especially in today’s church: the bible.

A few weeks ago I finished reading Thomas Torrance’s book Reality and Evangelical Theology. In this book, renowned theologian Thomas Torrance deals with an important issue, especially in today’s church: the bible.

How should we interpret the Scriptures?

Is the bible inerrant (perfect)? Or merely inspired?

Is the bible itself the truth or merely a witness to the truth?

I’ve already quoted the introduction of this book about fundamentalism and the scriptures (here), but I also wanted to post here my favorite quotes from the book. Not all of them have to do with scripture, but a large portion of them do. Later I plan to write an article about how this applies to the bible, but in the meantime enjoy these eleven quotes!

(All quotes are from the 1982 Westminster John Knox Pr. edition.)

_____________

“The fact that, through the free grace of God, Jesus Christ is made our righteousness means that we have no righteousness of our own.” (P. 18)

“No one may boast in his own orthodoxy any more than he may boast of his own righteousness. Justification thus turns out to be the strongest statement of the objectivity of faith and knowledge.” (P. 18)

“If God is not inherently and eternally in himself what he is towards us in Jesus Christ, as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, then we do not really or finally know God at all as he is in his abiding Reality.” (P. 24)

“…Since God has irreversibly incarnated his self-revelation in Jesus Christ, the Word made flesh, there cannot be two ways to knowledge of God, one in Jesus Christ and another behind his back, but only one way, through Christ and in his Spirit.” (P. 34)

“The development of fluid axioms which are continually open to change and renewal in the light of ever-deeper understanding of God means that the formulations of doctrine organized by reference to them must be open structures of thought and statement.” (P. 50)

“In a realist theology this will mean that we must distinguish no less sharply between dogmatic formulations of the truth and the truth itself, in the recognition that even when we have done all that it is our duty to do in relating them rightly (i.e., in an “orthodox” way) to the truth, they nevertheless fall far short of what they should be, and are inadequate. Indeed, it must be said that their inadequacy in this way is an essential part of their truth, in pointing away from themselves to the truth they serve, as it is an essential element in their objectivity in being grounded beyond themselves on reality that is independent of them.” (P. 50-1)

“The Holy Scriptures are the spectacles through which we are brought to know the true God in such a way that our minds fall under the compelling power of his self-evidencing Reality.” (P. 64-5)

“As such Jesus Christ is the Word through whom and with whom and in whom the true and faithful response of man is made to God and divine revelation completes the circle of its own movement.” (P. 86)

“Once and for all he [Jesus Christ] has become God’s exclusive language to man and he alone must be man’s language to God.” (P. 88)

“Strictly speaking, Christ himself is the scope of the Scriptures, so that it is only through focusing constantly upon him, dwelling in his Word and assimilating his Mind, that the interpreter can discern the real meaning of the Scriptures. What is required then is a theological interpretation of the Scriptures under the direction of their ostensive reference to God’s self-revelation in Jesus Christ and within the general perspective of faith.” (P. 107)

“That is to say, biblical statements are to be treated not as containing or embodying the Truth of God in themselves, but as pointing, under the leading of the Spirit of Truth, to Jesus Christ himself who is the Truth. We have to recognize the fact, therefore, that the Scriptures indicate much more than can be expressed, and that there is much more to their truth than can be reduced to words.” (P. 119)

Like this article? Share it!

December 31, 2015

Thomas Torrance on Fundamentalism and the Bible

I purchased an old, ex-library copy of Thomas F. Torrance’s Reality and Evangelical Theology (1981 Payton Lectures) a few months ago, and I am finally getting around to reading it. I wasn’t sure from the title what exactly to expect from the book, but after reading the preface I am pleasantly surprised. From what I have gathered so far, the premise of the book will essentially be to show how liberalism and fundamentalism make the same error, focusing specifically on the fundamentalists error in interpreting scripture. In Torrance’s own words, that “both [fundamentalism and liberalism] balk at the fact that God himself is the one ultimate Judge of the truth or falsity, the adequacy or inadequacy, of all human concepts and statements about him.” 1 And he claims that because of this, fundamentalists error in their reading of the bible.

I purchased an old, ex-library copy of Thomas F. Torrance’s Reality and Evangelical Theology (1981 Payton Lectures) a few months ago, and I am finally getting around to reading it. I wasn’t sure from the title what exactly to expect from the book, but after reading the preface I am pleasantly surprised. From what I have gathered so far, the premise of the book will essentially be to show how liberalism and fundamentalism make the same error, focusing specifically on the fundamentalists error in interpreting scripture. In Torrance’s own words, that “both [fundamentalism and liberalism] balk at the fact that God himself is the one ultimate Judge of the truth or falsity, the adequacy or inadequacy, of all human concepts and statements about him.” 1 And he claims that because of this, fundamentalists error in their reading of the bible.

I’m looking forward to reading more of his arguments on this matter, but here is a great quote from the preface that seems to highlight his primary issue with fundamentalism and their understanding of revelation and the scriptures. Enjoy!

…Fundamentalism operates with a rigid framework of beliefs which have a transcendent origin and which are certainly appropriated through encounter with God in his self-revelation and as such have an objective pole of reference and control, but these beliefs are not applied in a manner consistent with their dynamic origin and nature. Instead of being open to the objective pole of their reference in the continual self-giving of God and therefore continually revisable under its control, they are given a finality and rigidity in themselves as evangelical beliefs, and are clamped down upon Christian experience and interpretation of divine revelation through the Holy Scriptures. Thus they are endowed with a fixity at the back of the fundamentalist mind, where they are evidently secure from critical questioning, not only on the part of skeptical liberals and other freethinkers, but on the part of a divine self-revealing which is identical in its content with the very Being of God himself. At this point the epistemological dualism underlying fundamentalism cuts off the revelation of God in the Bible from God himself and his continuous self-giving through Christ and in the Spirit, so that the bible is treated as a self-contained corpus of divine truths in propositional form endowed with an infallibility of statement which provides the justification felt to be needed for the rigid framework of belief within which fundamentalism barricades itself.

The practical and the epistemological effect of a fundamentalism of this kind is to give an infallible Bible and a set of rigid evangelical beliefs primacy over God’s self-revelation which is mediated to us through the bible. This effect only reinforced by the regular fundamentalist identification of biblical statements about the truth with the truth itself to which they refer. 2

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Reality and Evangelical Theology P. 18, Thomas F Torrance, Westminster Press 1982 ↩ibid. P. 16-7 ↩December 6, 2015

The Best Books I Read in 2015

Last year around this time I set an important goal for myself for 2015: read 75 books. It is now December 6th, and I am happy to say that I’ve already read 76 books so far (with three weeks to go in the year!).

Last year around this time I set an important goal for myself for 2015: read 75 books. It is now December 6th, and I am happy to say that I’ve already read 76 books so far (with three weeks to go in the year!).

So here are my favorites!

I’ve divided them into five categories: Theology, General Christian, Literature/Fiction, Written Plays, and Memoirs. Here are my favorites in each category, followed by the honorable mentions!

Best Theology Book(s) I Read in 2015

A tie! I couldn’t decided between my two favorites from this year, both by two of my favorite theologians.

A tie! I couldn’t decided between my two favorites from this year, both by two of my favorite theologians.

The Trinity and the Kingdom by Jürgen Moltmann

and

The Christian Doctrine of God, One Being Three Persons by Thomas F. Torrance

Both books, quite apparently, are about the Trinity—my absolute favorite topic in theology! Because really, what else is there? When we talk about who God is we are at once talking about who God is for us and of the magnificent fact that God has taken hold of us and given us participation in His (Trinitarian) life! (This is an essential point I made in my book, which also emphasizes the Trinity, entitled We Belong: Trinitarian Good News.) The Trinitarian nature of the Christian God is perhaps one of the most profound ideas I’ve pondered in the last few years, and these two books present a brilliant, beautiful, and insightful summation of that doctrine.

The Trinity and the Kingdom was the 12th book I read by Jürgen Moltmann, and I must say I think it is my favorite! It not only presents a beautiful picture of the God who suffers with mankind, as he presented in The Crucified God, but a stunning picture of the Trinitarian life of God. For this reason I feel it’s one of his most complete books, one that I would recommend it to anyone looking for an introduction to Moltmann (alongside, Jesus Christ for Today’s World).

The Christian Doctrine of God is a great introduction to the thought of Thomas Torrance as well. Torrance was my first “theological love”. After reading The Mediation of Christ I knew I had found a theology worth pursuing. In this book Torrance presents a beautiful understanding of God as a Trinitarian Being.

Best General Christian Book I Read in 2015

This was also a tough one!

This was also a tough one!

But I must go with Benjamin Myers (from the blog Faith and Theology), and his wonderful little book entitled Salvation in My Pocket: Fragments of Faith and Theology.

Salvation in My Pocket is a collection of short, beautiful essays on a variety of topics from Bicycling through cities or meditation on Orthodox Icons, or on Karl Barth. But all the essays are incredibly inspiring, and intelligently written. I found myself sometimes brought to tears (or at least teary-eyed) by the incredible prose Benjamin has put forth in this book. I really enjoyed reading this collection of essays, and I know I will return to this book sometime in the near future!

Best Literature/Fiction Book I Read in 2015

No question about it, my favorite book in this category was James Joyce’s odd, beautiful, enigmatic, challenging, compelling, and fascinating novel Ulysses.

Ulysses is a notoriously difficult work of modern literature. But if you are willing to put in the work Joyce demands of you, you’ll see why this book has been called the greatest book every written in the English language. It is a feat in itself, a book that took nearly two decades to write. And it shows. The book is packed full of clever allusions, unique ways of writing, and wonderful little jokes (it is, at times, a hilarious book!).

I have written a blog that recounts my favorite quotes from Ulysses. Read it here!

Best Written Play I Read in 2015

This isn’t a category I would typically read, but I wanted to include it here for one reason alone: Samuel Beckett. I read a lot of Beckett this year, and though at first I disliked his style, I have come to enjoy his plays and novels. At first I found his writings to be far to depressing and nihilistic. But I kept running into a problem. Everyone I read was saying the opposite about him. Calling him one of the most important writers of our time (he won a nobel peace prize even!). So I knew I couldn’t give up on his works.

This isn’t a category I would typically read, but I wanted to include it here for one reason alone: Samuel Beckett. I read a lot of Beckett this year, and though at first I disliked his style, I have come to enjoy his plays and novels. At first I found his writings to be far to depressing and nihilistic. But I kept running into a problem. Everyone I read was saying the opposite about him. Calling him one of the most important writers of our time (he won a nobel peace prize even!). So I knew I couldn’t give up on his works.

And I am glad I stuck with him. He still daunts me from time to time but I find myself more and more siding with his perspective. There is no writer like Samuel Beckett, and if you want to read something that will explode your understanding of a novel or a play, read Beckett. He is not nihilistic, as I once thought. And while he can be bleak from time to time he is also very funny.

I do enjoy Beckett’s novels, but I think he is best known for his plays. And I enjoy these, oddly enough, the most. Particular two plays: Waiting for Godot (perhaps his most famous), and Krapp’s Last Tape.

In Waiting for Godot Beckett famously has written a play in which “nothing happens, twice”. Yet the dialogue and the general absurdity of the play makes it fascinating and at times compelling. (Watch the play here.)

In Krapp’s Last Tape Beckett shows who essential dialogues with himself on a recording from various years of his life. (Watch the play here.)

Best Memoir I Read in 2015

I am a tremendous fan of the music of Philip Glass, the prolific 20th century composer. His piano pieces especially are some of my absolute favorites! (Listen to an example here.)

I am a tremendous fan of the music of Philip Glass, the prolific 20th century composer. His piano pieces especially are some of my absolute favorites! (Listen to an example here.)

And, on a side note, he was just named amongst the 10 best composers of the 20th century by the BBC!

Earlier this year when he released his memoir, I was quick to order a copy. And I was not disappointed!

Words Without Music: A Memoir is not only my favorite biography/memoir from this year, but perhaps my favorite book from this entire list! I was deeply moved and inspired by this book. The life of Philip Glass and the journey he took to become such an important composer is an exciting and challenging thing to read. While reading I felt myself come alive with a desire to create beauty, to pursue art.

I recommend this memoir to any creative individual looking to be inspired by the one of the most important living composers!

Honorable Mentions

Theology:

Church Dogmatics Volumes II.2 and IV.1 by Karl Barth

(It was really hard not to include anything from Karl Barth in this list. But without a doubt these volumes of the Church Dogmatics are definitely noteworthy!)

The Spirit of Life: A Universal Affirmation by Jürgen Moltmann

The Way of Jesus Christ by Jürgen Moltmann

Jesus—God and Man by Wolfhart Pannenberg

(A challenging book! But one I plan to return to.)

General Christian:

Deliverance to the Captives by Karl Barth

What We Talk About When We Talk About God by Rob Bell

The Hardest Part by G. A. Studdert Kennedy

The Furious Longing of God by Brennan Manning

In the End—The Beginning: The Life of Hope by Jürgen Moltmann

Literature/Fiction:

Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce

(A great thriller novel written by a friend of mine!)

Written Plays:

(I’ve read it before, but I came to appreciate this play far more this year!)

I’d love to know your favorites, too! Leave me a comment with what books you enjoyed the most this year!

Like this article? Share it!

November 17, 2015

What is Election? (A Summary)

Anyone studying theology will eventually come across the perplexing problem of predestination. Is Calvin correct about God’s double-decree? Or is the Arminian approach correct? Do we choose God or does God choose us?

Anyone studying theology will eventually come across the perplexing problem of predestination. Is Calvin correct about God’s double-decree? Or is the Arminian approach correct? Do we choose God or does God choose us?

This was the first reason why I ever read Karl Barth. I had learned, through reading Thomas Torrance and C. Baxter Kruger, that Barth had written a new, revolutionary way to understand election.

But Barth can often be difficult to read. For the everyday Christian its challenging, nearly impossible for some, to pick up his large volumes filled with daunting paragraphs of dense theology. Is there any easier way to understand his doctrine of election?

Thankfully yes!

Barth Summarizing Election

Barth summarizes his doctrine of Election in several places, but one of the best I’ve come across was just recently while reading Deliverance to the Captives. The book is a collection of eighteen sermons Barth preached to prisoners in Basel, Switzerland. It’s a brilliant book, and a great example of Barth preaching the heart of the Church Dogmatics in a simple manner. As such, he talks about election in a way that is simple to understand, but backed by volume upon volume of brilliant theology.

In a sermon titled “Teach us to Number our Days” Barth gives this summary of election:

What happened in the death of Jesus did not happen against us, but for us. What took place was not an act of God’s wrath against man. Quite the opposite holds true. Because in the one Jesus God so loved us from all eternity—truly all of us—because He has elected Himself to be our dear Father and has elected us to become His dear children whom He wants to save and to draw unto Him, therefore He has in the one Jesus written off, rejected, nailed to a cross and killed our old man who, as impressively as he may dwell and spook about in us, is not our true self. God so acted for our own sake.

…The old man has already been extinguished in the death of Jesus, because you may no longer be this old man, because your own case has been disposed of by the power of Jesus’ death, therefore you yourself are now the new man, loved by God, chosen, saved and accepted by Him who has said to you and will say to you His divine “yes”. 1

Four Points

We could break this up into four points.

God elected first Himself to be our God, to be not just a God in the abstract, out there somewhere, but to be the God of mankind. He has chosen not to be only God alone in Himself, but to be God for us.

He eternally elected to be our Father. And therefore, in electing Himself, from all time He elected mankind in Jesus Christ, His Son, to be His adopted children. In electing Himself as Father, we are elected to become His children.

Jesus was excluded and rejected so that we might be included and accepted. Only(!) Jesus was rejected, and no one ever will be rejected as a result.

The old man is crucified and gone, taken away in Jesus’ death. We are free, included, saved, and healed in Christ.

These four points lead to the following conclusions. First, that God has chosen all people in His Son Jesus. Therefore no one is excluded from all eternity (compare this with Calvin’s horrible decree). Though this does not mean God takes sin lightly, and rejects no one. Instead, Jesus Christ, God and man, has taken up our cause, shouldered our responsibility, and undone our corruption in His death. He is the rejected man. God excluded Himself in order to include all people. None are excluded!

This contrasts starkly against Calvinism and Arminianism alike. For me, this solves the dilemma. We can now say that God is 100% for the human race, for each and every single person on the planet. He has no hidden decree about mankind, but has spoken a clear word in Jesus Christ, a “yes!” to mankind. It also means that we can affirm the grace of God in election, that we do not save ourselves but God saves single-handedly.

This, in simple terms, is what Barth has done with the doctrine of election. Barth places the central question back on Jesus Christ as both the electing God and the elected man. Election is about Him, and about us in Him.

For more on the doctrine of election see these quote from CD II.2. Also see my book We Belong: Trinitarian Good News, chapter one.

I recommend this book of sermons to anyone daunted by Barth’s reputation, but interested in hearing from how he presents the gospel. (Amazon link)

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

P. 122-3 ↩November 8, 2015

The Spirit of Life (Audio)

The Spirit of Life is a message I preached on Sunday November, 8th 2015 in Hope:Tallinn church. Enjoy!

Like this article? Share it!

October 27, 2015

Jesus and Nonviolence: A Third Way (Book Review)

I had the pleasure of reading Walter Wink’s short book Jesus and Nonviolence: A Third Way this weekend. It is on sale as a part of the Fortress Press eBook sale for only $3.99, so I figured it’s worth giving a try. I’ve heard of Walter Wink before, but this was my first time reading anything particular by him.

I had the pleasure of reading Walter Wink’s short book Jesus and Nonviolence: A Third Way this weekend. It is on sale as a part of the Fortress Press eBook sale for only $3.99, so I figured it’s worth giving a try. I’ve heard of Walter Wink before, but this was my first time reading anything particular by him.

Since reading Brian Zahnd’s brilliant book A Farewell to Mars I’ve taken interest in the topic of nonviolence as an agent for social change. And Wink’s book, as I’ve now discovered, is a classic on the topic. I enjoyed reading it and found it to be refreshing.

The book is important in helping clarify, at least for me, the way nonviolence actually works. Brian Zahnd’s book was excellent in showing why violence is a problem (especially in America), but only briefly hinted towards a way forward. Walter Wink picks up almost immediately where Zahnd left off. He writes to show what nonviolence actually looks like and perhaps most importantly what it does not look like. It is not passive action, or neutrality. It is sometimes fierce and critical as an act of militant resistance. He shows, through the teachings of Jesus, what this “third way” is (Jesus’ way compared to passivity or violence).

I also really enjoyed how Wink uses an abundance of stories from around the world to show when nonviolence worked. He draws a lot from Martin Luther King Jr., but also from many other nonviolent revolutions from South America, Europe, India, and Africa.

The book definitely got me thinking more about nonviolence as a realistic means of social change. It helped me understand the particular way in which Jesus presented nonviolence. We often misunderstand him to be teaching a passive response, when in fact his third way was an active, though nonviolence, form of resistance.

I recommend this book to anyone interested in nonviolence. Especially if you think of nonviolence only as nice theory but an ineffective one in practice. This book proves quite well that nonviolence is the way forward for humanity and our movement away from injustice.

To give you a preview of the book, here are a few quotes I enjoyed:

Jesus did not tell his oppressed hearers not to resist evil. That would be absurd… A proper translation of Jesus’ teaching would then be, “Don’t strike back at evil (or, one who has done you evil) in kind.” “Do not retaliate against violence with violence.” The Scholars Version is brilliant: “Don’t react violently against the one who is evil.” Jesus was no less committed to opposing evil than the anti-Roman resistance fighters. The only difference was over the means to be used: how one should fight evil. There are three general responses to evil: (1) passivity, (2) violent opposition, and (3) the third way of militant nonviolence articulated by Jesus. 1

Jesus abhors both passivity and violence as responses to evil. 2

Loving confrontation can free both the oppressed from docility and the oppressor from sin. 3

Once we determine that Jesus’ Third Way in not a perfectionistic avoidance of violence but a creative struggle to restore the humanity of all parties in a dispute, the legalism that has surrounded this issue becomes unnecessary. 4

Love of enemies is the recognition that the enemy, too, is a child of God. 5

We identify someone else as evil and unconsciously project our own evil onto that person. 6

To be very frank with you, I don’t think that violence is Christian. Some may say that this is a reactionary position. But I think that the very essence of Christianity is the cross. It is through the cross that we will change. 7

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

pp. 10-11 ↩p. 13 ↩p. 26 ↩p. 51 ↩p. 59 ↩p. 79 ↩p. 85 (All quotation taken from the Fortress Press Kindle edition of 2003) ↩