Stephen D. Morrison's Blog, page 12

May 8, 2016

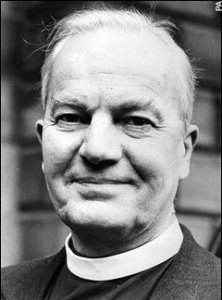

Thomas F. Torrance on Preaching Christ Today

Several months ago I finished reading Thomas F. Torrance’s short book Preaching Christ Today. For anyone who’s never read Thomas Torrance, and perhaps feels too daunted by his academic strength, you should read this book. It is an excellent introduction to some of his most significant contributions to theology, and it highlights quite well why I love reading his work: T.F. Torrance is a scientific thinker because he is an evangelical thinker. He writes with this end in mind, to preach the gospel, to evangelize the world even in the discipline of modern science (which is often wrongly seen as an antithesis to theology). I have a lot of respect for what Torrance has done for theology, not only for the church but for my life personally. It was in Torrance that I first encountered an understanding of God that shattered all my images of him, revealing himself to be a God of infinite grace and love. So without a doubt, this short book is an inspiring read as well. Just as Barth’s sermons to prisoners at Basel, Deliverance to the Captives, is a great starting point for his theology, so this book is great for Torrance. Today I wanted to put together several great quotes from the book that I enjoyed. (All quotes are from the 1994 Eerdmans edition.)

Several months ago I finished reading Thomas F. Torrance’s short book Preaching Christ Today. For anyone who’s never read Thomas Torrance, and perhaps feels too daunted by his academic strength, you should read this book. It is an excellent introduction to some of his most significant contributions to theology, and it highlights quite well why I love reading his work: T.F. Torrance is a scientific thinker because he is an evangelical thinker. He writes with this end in mind, to preach the gospel, to evangelize the world even in the discipline of modern science (which is often wrongly seen as an antithesis to theology). I have a lot of respect for what Torrance has done for theology, not only for the church but for my life personally. It was in Torrance that I first encountered an understanding of God that shattered all my images of him, revealing himself to be a God of infinite grace and love. So without a doubt, this short book is an inspiring read as well. Just as Barth’s sermons to prisoners at Basel, Deliverance to the Captives, is a great starting point for his theology, so this book is great for Torrance. Today I wanted to put together several great quotes from the book that I enjoyed. (All quotes are from the 1994 Eerdmans edition.)

Quotes:

“This is the end to which my own life has been dedicated. What I have been trying to do is to show how the gospel can be taught and preached in ways that are faithful to the apostolic faith as it was brought to authoritative expression in the Nicene Creed, and at the same time may be taught and preached today in ways that can be expressed and appreciated within the scientific understanding of the created universe upon which God has impressed his Word and which under God was have been able to develop in modern times. Far from being hostile to one another, Christian theology and natural science are complementary to one another.” (Preface, vii)

“The real Jesus of history is the Christ who cannot be separated from his saving acts, for his person and his work are one, Christ clothed with his gospel of saving grace. The so-called Jesus of history shorn of theological truth is an abstraction invented by a pseudo-scientific method.” (P. 9)

“What overwhelms me is the sheer humanness of Jesus, Jesus as the baby at Bethlehem, Jesus sitting tired and thirsty at the well outside Samaria, Jesus exhausted by the crowds, Jesus recuperating his strength through sleep at the back of a ship of Galilee…for that precisely is God with us and one of us, God as ‘the wailing infant’ in Bethlehem, as Hilary wrote, God sharing our weakness and exhaustion, God sharing our hunger, thirst, tears, pain, and death… He does not override our humanity but completes, perfects, and establishes it.” (p. 13)

“In giving his own dear Son to die for us in atoning sacrifice for the sins of the world, God has revealed that he loves us more than he loves himself.” (p. 28)

“In him we believe that God himself has come into the midst of our human agony and our abominable wickedness and violence in order to take all our guilt and our just judgement on himself. That is for us the meaning of the cross. If I did not believe in the cross, I could not believe in God. The cross means that, while there is no explanation of evil, God himself has come into the midst of it in order to take it upon himself, to triumph over it and deliver us from it.” (p. 29)

“Faith in Christ involves a polar relation between the faith of Christ and our faith, in which our faith is laid hold of, enveloped, and upheld in his unswerving faithfulness.” (p. 31)

“In far too much preaching of Christ the ultimate responsibility is taken off the shoulders of the Lamb of God and put upon the shoulders of the poor sinner, and he knows well in his heart that he cannot cope with it.” (p. 35)

“During those years what imprinted itself upon my mind above all was the discovery of the deepest cry of the human heart: Is God really like Jesus? This came home to me very sharply one day on a battle field in Italy, when a fearfully wounded young lad, who was only nineteen and had but half an hour to live, said to me, ‘Padre, is God really like Jesus?’ I assured him as he lay upon the ground with his life ebbing away that God is indeed really like Jesus, and that there is no unknown God behind the back of Jesus for us to fear, to see the Lord Jesus is to see the very face of God.” (p. 55)

That last quote always gets to me! This is why I read theology and attempt what little I can to write it, because the world needs to know this simple truth. God really is like Jesus! And few theologians have shown this fact better than Thomas F. Torrance.

Like this article? Share it!

April 29, 2016

A Preach-able Theology (Announcing New Book)

I’ve always felt that Karl Barth, along with the others who have followed after him like Thomas F. Torrance and Jürgen Moltmann, is such a great theologian not only because of his genius in theology (which goes without saying), but because of the gospel he preaches. I read theology for this reason (beyond the enjoyment I take from it!), because I’m looking for a theology that preaches truly good news to a world desperately in need of hope. This is why I write so much about thinkers like Karl Barth, Thomas F. Torrance, and Jürgen Moltmann on this website; they’ve helped me come to grips with a truly “preach-able gospel.”

I’ve always felt that Karl Barth, along with the others who have followed after him like Thomas F. Torrance and Jürgen Moltmann, is such a great theologian not only because of his genius in theology (which goes without saying), but because of the gospel he preaches. I read theology for this reason (beyond the enjoyment I take from it!), because I’m looking for a theology that preaches truly good news to a world desperately in need of hope. This is why I write so much about thinkers like Karl Barth, Thomas F. Torrance, and Jürgen Moltmann on this website; they’ve helped me come to grips with a truly “preach-able gospel.”

Theology and practice are not two separate fields, they’re one and the same. Whatever is truly theological is at once practical. As my friend Marty Folsom shared on Facebook about a week ago: “If theology only debates issues that bore the congregation and keep the neighbors from wanting to come to church, it seems to have abandoned the humanity of God that engages everyday life. Can theology be theologically rational if it is not profoundly relational?”

This is why I read theology, and these are the kinds of books I want to write—books that engage with the everyday lives of human beings.

With this goal in mind I’m happy to announce a short attempt to do exactly this: to preach a theological gospel, to take the theology I’ve learned (and am still learning) from Barth and others and to make it clear, approachable, and preach-able. In short, to “preach the gospel to all creation.”

I’ve written Welcome Home: The Good News of Jesus as a sort of gospel tract (as much as one can in the digital age). My hope is that anyone could pick it up and relate to it, while at once being challenged by it. Though it’s perhaps written most of all for anyone asking the question, “What makes the good news good?” (A question I was once asking and still am asking, and which has sent me on a long journey over the last six years of rediscovering the gospel.) It’s a very (very) short book, more of a booklet than anything, coming in just over 12k words. But it is also packed full of food for thought and deep ideas. Students of Barth will undoubtably notice many similarities between this book and Barth’s theology, but there’s also a debt owed to Thomas F. Torrance and Jürgen Moltmann.

Overall it’s not about Barth or Torrance or Moltmann; it’s about Jesus. My heart is warmed as I read it over once again, as I’m reminded in my own words of what God has done for me in Jesus Christ. The ultimate goal is to see Jesus better, with the help of some very intelligent people, and to encounter His love for humanity as it was put on full display through His life, death, and resurrection.

So without further ado, here’s where you can download my new book (Did I mention it’s free? It is!):

Download now from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and iBooks.

Please share this however you can, with whoever you’d like, and help me spree the word! It’s permanently free like my other book, and so I hope it has a lasting impact with a large reach!

April 24, 2016

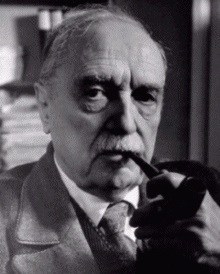

A New Theological Adventure: Reading Rudolf Bultmann

Today I began a “new theological adventure” as I picked up a book I’ve been excited to read for sometime now: David W. Cogdon’s Rudolf Bultmann: A Companion to His Theology. (Link.) So far I’ve enjoyed the book a lot, and it has sparked a deeper interest in Bultmann than I already had. I know of Bultmann through reading Barth; although because it’s by reading Barth that I know Bultmann, I’ve come to know Bultmann negatively, as an unreconcilable figure theologically.

Today I began a “new theological adventure” as I picked up a book I’ve been excited to read for sometime now: David W. Cogdon’s Rudolf Bultmann: A Companion to His Theology. (Link.) So far I’ve enjoyed the book a lot, and it has sparked a deeper interest in Bultmann than I already had. I know of Bultmann through reading Barth; although because it’s by reading Barth that I know Bultmann, I’ve come to know Bultmann negatively, as an unreconcilable figure theologically.

But after reading about a third of Cogdon’s book this morning, I am looking forward to the challenging but interesting task of learning more from Bultmann, and, in another sense, to understand Barth better accordingly. In the foreword of CD IV.1 Barth notes that he is engaging with Bultmann throughout the volume, saying: “…I have found myself in an intensive, although for the most part quiet, debate with Rudolf Bultmann. His name is not mentioned often. But his subject is always present…” Barth continues to say how he respects Bultmann, but that he wishes he could do him greater justice. Their relationship has been described by Barth as the meeting of an elephant and a whale “with boundless astonishment on some oceanic shore.” (The Postbartian has a great article on this.)

So I have often thought that Barth and Bultmann are a lot like Barth and Schleiermacher: polar opposites, diametrically opposed to one another. But as I’m beginning to see, thanks to David’s book, this isn’t necessarily true. They definitely had their differences, but there’s a lot in common with them as well. An interesting insight from the first chapter where Cogdon discusses Bultmann’s eschatology revealed that early Barth and Bultmann shared the same outlook. Barth later left this behind, but Bultmann continued in the same track.

In this article I wanted to outline some of the resources I plan to explore, including books and articles on Bultmann, as I dive into the thought of Bultmann.

First, I am planning to finish Cogdon’s book and maybe even write a full article on what I learn. But after that I will dive into the following resources I’ve found around the web, and books I own.

(All resources are primary sources, with the exception of Barth’s essay on Bultmann.)

Web links:

“History and Eschatology” – Gifford Lectures

“The Concept of Freedom in Christianity and Classical Antiquity” – Audio Lecture

“Jesus and the Word” – PDF from Religion-Online

“Kerygma and Myth” – PDF from Religion-Online

“Rudolf Bultmann—An Attempt to Understand Him” – By Karl Barth

Books:

At the moment I only have two books on my shelf from Bultmann, but they are his two of most well-known (as far as I can tell): Jesus Christ and Mythology and Theology of the New Testament.

I’ll probably begin with the first, after going through the web links with special interest in Barth’s essay on Bultmann. Cogdon has a list of recommended books in the back of his book, and so I’ll probably be adding a few of those as well to my small collection. I might even brave Cogdon’s massive (1,000 page) work on Bultmann: The Mission of Demythologizing. But one step at a time.

Until then I’m looking forward to reading Bultmann firsthand and exploring his thought, which seems as fascinating as it is complex.

Like this article? Share it!

April 20, 2016

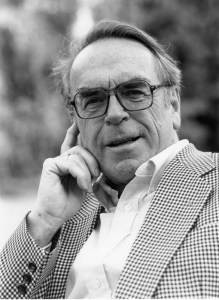

The Quote that Made Me Read Jürgen Moltmann

I was writing something about Jürgen Moltmann the other day, and for some reason it had me think back to the first quote I read from him that really won me over. The quote convinced me to finally pick up that daunting book on my shelf called The Crucified God. The quote remains one of my favorite quotes from Moltmann, even today. Jürgen Moltmann is one of my top three favorite theologians (next to Barth and Torrance), and I was happy to see how much of his work I’ve read since this quote. I’ve read now fourteen books from Moltmann, and plan to read at least fourteen more (and re-read even more). But going back to where it all started, here’s the quote that made me love Jürgen Moltmann.

I was writing something about Jürgen Moltmann the other day, and for some reason it had me think back to the first quote I read from him that really won me over. The quote convinced me to finally pick up that daunting book on my shelf called The Crucified God. The quote remains one of my favorite quotes from Moltmann, even today. Jürgen Moltmann is one of my top three favorite theologians (next to Barth and Torrance), and I was happy to see how much of his work I’ve read since this quote. I’ve read now fourteen books from Moltmann, and plan to read at least fourteen more (and re-read even more). But going back to where it all started, here’s the quote that made me love Jürgen Moltmann.

The SS hanged two Jewish men and a youth in front of the whole camp. The men died quickly, but the death throes of the youth lasted for half an hour. ‘Where is God? Where is he?’ someone asked behind me. As the youth still hung in torment for a long time, I heard the man call again, ‘Where is God now?’ And I heard a voice in myself answer: ‘Where is he? He is here. He is hanging there on the gallows…’

Any other answer would be blasphemy. There cannot be any other Christian answer to the question of this torment. To speak here of a God who could not suffer would make God a demon. To speak here of an absolute God would make God an annihilating nothingness. To speak here of an indifferent God would condemn men to indifference. 1

Technically the first half of the quote is from E. Wiesel’s book Night (a fantastic book in its own right), but this quote gets to the core of Moltmann’s theology. It struck me so profoundly, as it still does today, that I knew I had to read Jürgen Moltmann. What’s your favorite quote?

I’ve since written a book engaging Moltmann with the question of God and human suffering, and you can download it for free right now when you join my Readers Group!

Notes:

Jurgen Moltmann, The Crucified God, p 273-274 ↩April 18, 2016

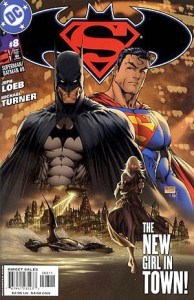

Is God More Like Batman or Superman?

It could just be a matter of opinion. But whenever I think about who’s the more compelling character, Batman or Superman, it’s Batman hands down.

It could just be a matter of opinion. But whenever I think about who’s the more compelling character, Batman or Superman, it’s Batman hands down.

This weekend Ketlin and I went to see the new Batman Vs. Superman movie, and I was thinking a lot about this watching it. Without commenting on the movie itself, which I did enjoy, it was clear to me in comparing these two stories who was the more relatable, compelling superhero. Batman was who I found myself rooting for, even if in this movie he was slightly misguided by some bad assumptions.

Here’s why I find Batman more compelling. 1) He’s a human character with real emotions; a man who can suffer and die. 2) He changes, both in character and in opinion. He’s flawed, and he’s in process.

In contrast, Superman is less compelling. 1) He acts like an inhuman character barely with any emotion. While he has suffered the loss of others, he has hardly suffered himself. And he can’t die. So what does he really risk in the end? 2) He’s often portrayed as a moral absolute, who’s rarely wrong. He rarely changes his mind because he is this moral absolute.

In the final analysis Batman will always be, at least for me, the more relatable character, the character who risks the most, suffers the most, and who grows the most. Superman falls flat in comparison.

Now here’s an interesting question: which character is more like the God of Jesus Christ?

In traditional theology the answer is simple. God cannot suffer or die; God cannot change. In technical terms, God is impassible and immutable. Therefore, God is more like Superman.

But does this mean we have a God we cannot relate to? In a sense: an inhuman God, an abstract divinity?

Jürgen Moltmann once said, in response to the horrors of the holocaust, “To speak here of a God who could not suffer would make God a demon.” 1 And Dietrich Bonhoeffer has also said, “Only the suffering God can help.” 2

If God cannot suffer in the face of our suffering, if God is incapable of suffering, God is a demon. An impassable God is a cold God who remains unaffected by our human calamity. But thankfully this is not the God of Jesus Christ.

We often imagine that God is like Superman. That God is some absolute power from another planet, unable to suffer, unable to die. A God created in our image may be like this, but this is not the God revealed in Jesus Christ. The God revealed in Jesus is a God subject to suffering, a God who humbles Himself to become vulnerable and weak, and even a God who dies.

The God of abstract philosophy, the impassable and immutable God, is an inhuman God. We cannot relate to this God. Perhaps this is why so many give up on God in the face of tragedy and hardship? Isn’t that the common question? Where is God in suffering? If God exist, why hasn’t he done anything about suffering?

But in Jesus Christ God stands in solidarity with mankind and our suffering. God suffers with us. As Jürgen Moltmann says, “God weeps with us so that we may one day laugh with Him.”

God is not Batman, but in the face of suffering and death God is closer to him than Superman. Because in Jesus Christ God truly and actually risked Himself, He truly and actually suffered and died. And therefore, we have a brother in suffering, a friend in death. We are never alone in our darkness.

(For more on God and human suffering, see my book, Where Was God?, currently FREE when you sign up to my Readers Group.)

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

The Crucified God, P. 274 ↩ Letters and Papers from Prison ↩April 9, 2016

Karl Barth’s Doctrine of Faith in CD IV.1

Continuing with the last few weeks, as I’ve been writing my way through parts of Karl Barth’s volume IV.1 of the Church Dogmatics, today I’ll be presenting Barth’s doctrine of faith.

(As before all page numbers refer to the Hendrickson edition of 2010.)

In typically dialectic manner, Barth begins with defining faith as that which “has to be done” by the individual, but which “cannot be done naturally.” (P. 614) As such, faith is a human work but a unique sort of work. (By work here it is meant not as “self-justification,” as Barth later explains. Instead, work refers to faith as a human act.) It is unique in that we cannot perform it, but we must. We cannot have faith, but we must. Like speaking of God, the task of theology, we cannot do this naturally. But since in Jesus Christ God has spoken to us, we must. So with faith, although we cannot naturally have faith, we must because the object of faith (Jesus Christ) is faithful to us. The faithfulness of Jesus requires a corresponding response. It is not a faithfulness that takes place over our heads or behind our backs, so to speak, and therefore it confronts us demanding this response. Faith is this response, however inadequate we are to make it in ourselves. This brings us to what the apostle Paul has said, that faith is a gift (see Eph. 2:8).

Accordingly, faith is a divine work which is at once a human work which corresponds to that divine work. (Cf. p. 615)

From here Barth continues to develop the negative side of faith, that which it cannot be. Faith cannot be a form of self-justification in which man saves himself. Barth writes, “It is not in and with all this that a man justifies himself, that he pardons himself, that he sets himself in that transition from wrong to right, from death to life, that he makes himself the subject of that history, the history of redemption. There is always something wrong and misleading when the faith of a man is referred to as his way of salvation…” (P. 616)

Faith, instead is “wholly and utterly humility.” (P. 618) And as humility it cannot be self-justification as this would ultimately be only another for of human sin which is pride.

This is how Barth begins to define faith under the heading “Justification by Faith Alone.” In general terms he does two things with this. He at once affirms faith as the response of mankind to Gods faithfulness, and yet he takes the center of faith away from man and places it upon the objective grounds of Jesus Christ. Faith is what we must do though cannot do, yet in Christ that which has been done in our place, that which we take part in.

After this Barth brilliantly continues not with further describing faith, but with the community of faith. I found this section to be one of the most compelling, especially in the overly individualize American culture I grew up in. Because for Barth, faith is the faith of a human community. It is essential that faith is not an abstract principle, an individual act, but that which is done in the community of Jesus Christ: the church. As faith is a human act, so it must be an act within community. Barth writes, “A private monadic faith is not the Christian faith.” (P. 678) Because, as Barth writes later, “By nature humanity means fellowship. …Since faith is his free human act, he cannot perform it without his neighbors…” (P. 778)

To be human without community is not to be human at all, therefore a faith without community is not Christian faith. Accordingly, faith is the act within the specifically human community of Jesus Christ, His body, the church. Barth writes to great length about the being of this community.

He picks up the subject of faith again in the final section of the volume, section 63 called, “The Holy Spirit and Christian Faith.” This section has two headings, first on Faith and its Object, second on The Act of Faith.

Faith is not for Barth a general term, but instead means particularly faith in Jesus Christ. It is only true faith in relation to its object upon which it is based. These two distinctions are essential.

Faith is faith only in relation to its object, Jesus Christ. As Barth puts it, “Faith stands or falls with its object.” (P. 742) Faith is faith only in this relationship. Barth presents a beautiful picture for this:

“Faith does not realize anything new. It does not invent anything. It simply finds that which is already there for the believer and also for the unbeliever. It is simply man’s active decision for it, his acceptance of it, his active participation in it. This constitutes the Christian. In believing, the Christian owes everything to the object of his faith. … This distinguishes the Christian from the non-Christian. The object [think Jesus Christ] is like a circle enclosing all men and every individual man [and woman]. In the case of the Christian this circle closes with the fact that he believes. In the case of the non-Christian it is still open at the point where he ought to believe but does not believe, or no longer believes. The unbeliever has not accepted the relationship which is in relationship to him. He is abnormal in this respect. Faith is the normalizing of the relationship between man and this object.” (P. 742)

Barth seems to be saying here that all humanity is enclosed within this circle, within the object, and the only difference is that a believer is normal and accepts this while an unbeliever abnormally does not. Wonderfully, this could be said another way. Jesus Christ is in relationship with all humanity, we cannot make this happen ourselves. Yet those who accept this respond with faith. While those who do not still remain within this circle. A similar conclusion was made in my book, We Belong: Trinitarian Good News.

Barth continues by defining this object:

“…The ‘object’ …is Jesus Christ, in whom God has accomplished the reconciliation of the world.” (P. 742)

The second consideration is to say further that faith is not only in relation to Jesus Christ, but it is “based upon [Him].” Barth says that while faith is genuinely a human act, the most genuinely human act in fact, it is “also the work of Jesus Christ. It is the will and decision and achievement of Jesus Christ the Son of God that takes it takes place as a free human act…” (P. 744)

Finally, Barth reaches this conclusion of Faith and its object.

“The Son makes a man free to believe in Him. Therefore faith in Him is the act of a right freedom, not although but just because it is the work of the Son. A man does not have this freedom unless the Son makes him free.”

Here Barth continues with the Holy Spirit as the awakening power which confronts man, illuminating what is true. He writes, “The Holy Spirit is the power in which Jesus Christ the Son of God makes man free, makes Him genuinely free for this choice and therefore for faith.” (P. 748)

Then in my favorite quote from this section he says this. “Faith is at once the most wonderful and simplest of things. In it man opens his eyes and sees and accepts everything as it—objectively, really, and ontologically—is. Faith is the simple discovery of the child which finds itself in the father’s house and on the mother’s lap.” (P. 748)

The third and final thing comes when faith takes on the form of constituting a new Christian subject, a “new creation.” This is what faith sees, that God in Christ is for me, that I belong to Him, that I am His beloved child elected in Christ Jesus. Faith as such has a cognitive character and not a creative one. It does not produce this new man, but recognizes him. (Cf. pp. 751-5)

In the final section Barth understands the act of faith as acknowledgement, recognition, and confession.

There is much more that could be said here about Barth’s doctrine of faith, but here we have in general terms a better understanding of what faith is, and most importantly the object of faith.

(My apologies for the poor formatting here. My laptop has broken and so I’ve written this on my iPad. Once it’s fixed I’ll be able to clean this up more.)

April 6, 2016

8 Brilliant Karl Barth Quotes on Atonement (CD IV.1 Summarized)

Karl Barth’s doctrine of reconciliation, found in volume IV.1 of his Church Dogmatics, is without a doubt one of the greatest theological works ever written on the subject. And it is personally my favorite volume from the Church Dogmatics. In this volume Barth beautifully and masterfully describes what has taken place for all mankind in Jesus Christ, the God who became man to reconcile the world to Himself.

Karl Barth’s doctrine of reconciliation, found in volume IV.1 of his Church Dogmatics, is without a doubt one of the greatest theological works ever written on the subject. And it is personally my favorite volume from the Church Dogmatics. In this volume Barth beautifully and masterfully describes what has taken place for all mankind in Jesus Christ, the God who became man to reconcile the world to Himself.

Today I wanted to continue with my attempt of summarizing each volume of the Church Dogmatics into a collection of quotes. I’ve done this already with volumes II.2 and I.1. And as before, I have limited myself to one quote for every 100 pages. And while it certainly goes without saying that Barth here is far too complex to be simplified into eight quotes, however, I have chosen these quote to attempt to give a very broad and general overview of the volume. And hopefully, if you have not already read the volume, to encourage you to read it yourself! It is a beautiful work of theology, and I cannot recommend it more highly.

So without any more introduction, here are eight quotes to summarize CD IV.1. Enjoy!

(All page references are taken from the Hendrickson Publishers 2010 edition.)

CD IV.1 Summarized in 8 Quotes

“‘God with us’ is the centre of the Christian message—and always in such a way that it is primarily a statement about God and only then and for that reason a statement about us men.” (p. 5)

“[Jesus Christ] is the atonement as the fulfillment of the covenant.” (p. 122) “To say atonement is to say Jesus Christ.” (p.158)

“The passion of Jesus Christ is the judgement of God in which the Judge Himself was judged.” (p. 254)

“He Himself, Jesus Christ, the Son of God made man, was justified by God in His resurrection from the dead. He was justified as man, and in Him as the Representative of all men all were justified.” (pp. 305-6)

(I’ve written more on this idea here: “God Justifies Himself.”)

“…We maintain the simple thesis that only when we know Jesus Christ do we really know that man is the man of sin, and what sin is, and what it means for man.” (p. 389)

(I’ve written more on this idea here: “Karl Barth’s Revolutionary Doctrine of Sin.”)

“It is as God identifies Himself with man—His participation and intervention is as direct and complete as that—it is as He becomes a man and as this man the Representative of all men, it is as He makes His own the cause of all men that justification can and does take place.” (p. 551)

“A private monadic faith is not the Christian faith.” (p. 678)

“Faith is at once the most wonderful and the simplest of things. In it a man opens his eyes and sees and accepts everything as it—objectively, really and ontologically—is. Faith is the simple discovery of the child which finds itself in the father’s house and on the mother’s lap.” (p. 748)

(See also this extended quote for Easter.)

Like this article? Share it!

March 26, 2016

“I Know Someone Who Was in Hell: Christ” (Moltmann)

Happy Holy Saturday!

Happy Holy Saturday!

Holy Saturday, especially in protestant churches, is a deeply under appreciated part of the Easter story. In recent years, though, as I’ve meditated more on what it means, I’ve become convinced that Holy Saturday is just as essential to the gospel as Good Friday and Easter Sunday. Let me explain why.

Holy Saturday is the day in which Christ was buried in the grave, and descended to hell (as the Apostles Creed proclaims. “He suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried; he descended to hell. The third day he rose again from the dead.”) The significance of this day is brought out, at least for me personally, most of all in the works of Jürgen Moltmann. For Moltmann, Christ’s descent to hell is a further movement of His solidarity with mankind. As on the cross Jesus suffered our forsakenness and our death, so too in the grave Jesus suffered our hell. He went so far as our God acting for us that He not only overcame our sin and death, but our hell too. Jesus has bankrupted hell, robbing it of any power it once had over mankind. He has defeated the grave. Truly, we can say with Paul: “Death where is your sting? Grave where is your victory?”

Here Moltmann writes in Jesus Christ for Today’s World on this descent to hell:

“Is there a hell?

Yes, I believe there is a hell. In the horrors of Auschwitz and in the terrors of Vietnam, people experienced a hell of suffering and a hell of guilt. That is why we talk about the hell of Auschwitz and the hell of Vietnam, meaning a senseless suffering with no way out, an unforgivable guilt and a fathomless abandonment by God and human beings. Is there a hell after death too? I believe there is, for the hell before death is worse than death itself. For many people death was a release from the suffering and fear of that hell.

Do we know anyone who is in hell? Would we tell a mother weeping at her son’s grave that her son is in hell because he never found faith while he was alive? We should respond to the first question with an embarrassed silence. And we would not answer ‘yes’ to the second one either. But I know someone who was in hell: it is Jesus Christ, who the creed says ‘descended into hell’.

When we were thinking about the tortured Christ, we asked: what does this article in the creed mean? When did Christ go through hell? And we saw that in the past two answers have been given. The earlier interpretation said that after his death Christ descended to the realm of the dead, to preach to them the gospel of their redemption and to deliver them. Luther looked at it differently, maintaining that Christ endured the torments of hell between Gethsemane and Golgotha, in his profound forsakenness by God. But whatever we may think about Christ’s descent into hell, Luther was right when he said: ‘Regard not hell and the eternity of torment in thyself, nor these things in themselves, nor yet in those who are damned. Look upon the face of Christ, who for thy sake descended into hell and was forsaken by God as one who is damned eternally, as he said on the cross: “My God, why hast thou forsaken me?” See, in him thy hell is vanquished …’ Because Christ was in hell and endured its torments, there is hope in hell for redemption. Because Christ was raised to life from hell, hell’s gates are open and its walls have been broken down. Though I make my bed in hell, you are there.’ And then hell is not hell any longer. ‘O hell where is thy victory? But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ? (1 Cor. 15:55, 57).” 1

Hell Overcome

Hell is overcome by Christ. Whatever else we have to say about hell, it’s duration or existence or who goes there—we can say for certain this: hell is overcome. And we only know with certainty of one who has been there: Jesus Christ. This means that even in hell, there is hope. Because even in hell there is Jesus Christ the reconciler of the world, the redeemer of mankind, the friend of sinners.

This does not, of course, automatically equate to universalism. As Karl Barth has said about the subject, “I don’t teach universal reconciliation but I don’t not-teach it.” Because in the end the question of universalism is not something we can answer. Instead, it will only be answered by God. As Jürgen Moltmann has also said, “Does the new creation of all things mean ‘universal reconciliation’ and ‘the restoration of all things’? This is a difficult question, because only God will answer it. If we think humanistically and universally—God could perhaps be a particularist. But if we think pietistically and particularistically—God might be a universalist. If I examine myself seriously, I find that I have to say: I myself am not a universalist, but God may be one.” 2

If we take seriously the scope of Christ’s redemption, and the solidarity He has taken up with mankind, it’s impossible, in my mind, not to have at least some hope for the redemption of all creation. We cannot claim factually that all will be saved. But we can, and must, have hope for it. And we have hope for it because in Christ we see only this hope, the hope that all will be saved.

(For more see further my book We Belong: Trinitarian Good News appendix B, along with Dare We Hope That All Men Be Saved? by Hans Urs von Balthasar.)

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Moltmann, J. (1994). Jesus Christ for Today’s World. (M. Kohl, Trans.) (pp. 143–145). Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. ↩Moltmann, J. (1994). Jesus Christ for Today’s World. (M. Kohl, Trans.) (pp. 142–143). Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. ↩March 25, 2016

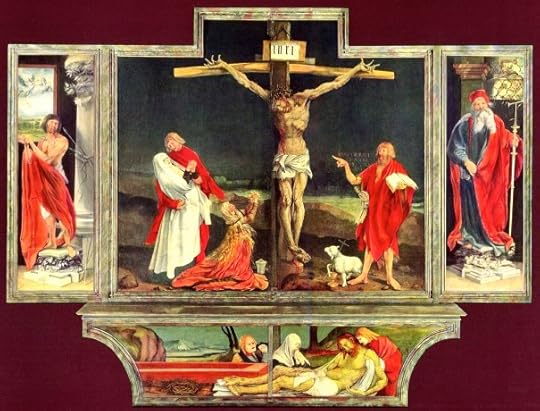

Not One – Good Friday Meditation

Happy Easter and a very blessed Good Friday to you!

I hope you have the time today to sit and meditate on what Jesus Christ has done for the human race in His death, resurrection, and ascension. This gospel is truly good news of great joy! Jesus became one of us rescuing us from death and sin by dying our death, raising us again to new life, and seating us with Him in heavenly places. Today calls for the celebration and remembrance of this marvelous truth!

Yesterday, I was reading Karl Barth, as I’ve mentioned before, in his Church Dogmatics volume IV.1. As I read I came across a magnificent passage I want to share with you today. Here Barth writes about the objective work of Jesus Christ for all people, what He has done on the cross for all mankind in justifying us and obliterating our sin. It is a beautiful passage on what Jesus has done for the human race, and I was struck with emotion when I read it. It is a perfect reminder as we contemplate and remember what Jesus has done for us! Enjoy!

If you’re looking for something to listen to today, I’ll be listening to the music of Arvo Pärt. Here’s an especially appropriate choral work called “Passio” which follows Johns account of the crucifixion. It’s very beautiful!

Enjoy!

Not One

“But the self-demonstration of the justified man to which faith clings is the crucified and risen Jesus Christ who lives as the author and recipient and revealer of the justification of all men. It is in Him that the judgement of God is fulfilled and the pardon of God pronounced on all men. …It happened that in the humble obedience of the Son He took our place, He took to Himself our sins and death in order to make an end of them in His death, and that in so doing He did the right, He became the new and righteous man. It also happened that in His resurrection from the dead He was confirmed and recognised and revealed by God the Father as the One who has done and been that for us and all men. As the One who has done that, in whom God Himself has done that, who lives as the doer of that deed, He is our man, we are in Him, our present is His, the history of man is His history, He is the concrete event of the existence and reality of justified man in whom every man can recognise himself and every other man—recognise himself as truly justified. There is not one for whose sin and death He did not die, whose sin and death He did not remove and obliterate on the cross, for whom He did not positively do the right, whose right He has not established. There is not one to whom this was not addressed as his justification in His resurrection from the dead. There is not one whose man He is not, who is not justified in Him. There is not one who is justified in any other way than in Him—because it is in Him and only in Him that an end, a bonfire, is made of man’s sin and death, because it is in Him and only in Him that man’s sin and death are the old thing which has passed away, because it is in Him and only in Him that the right has been done which is demanded of man, that the right has been established to which man can move forward. Again, there is not one who is not adequately and perfectly and finally justified in Him. There is not one whose sin is not forgiven sin in Him, whose death is not a death which has been put to death in Him. There is not one whose right has not been established and confirmed validly and once and for all in Him. There is not one, therefore, who has first to win and appropriate this right for himself. There is not one who has first to go or still to go in his own virtue and strength this way from there to here, from yesterday to to-morrow, from darkness to light, who has first to accomplish or still to accomplish his own justification, repeating it when it has already taken place in Him. …There is not one whose peace with God has not been made and does not continue in Him. There is not one of whom it is demanded that he should make and maintain this peace for himself, or who is permitted to act as though he himself were the author of it, having to make it himself and to maintain it in his own strength. There is not one for whom He has not done everything in His death and received everything in His resurrection from the dead.

Not one. That is what faith believes.”

(Karl Barth Church Dogmatics IV.1 Hendrickson Publishers, 2010, pp.629-630)

Like this article? Share it!

March 20, 2016

God Justifies Himself – (Barth Reflections from CD IV.1 §61)

[image error]Happy Palm Sunday!

Today, as with two weeks ago, I’m continuing by writing my way through Karl Barth’s masterful volume in the Church Dogmatics: volume IV.1, on the doctrine of reconciliation. It has been a fitting read as we come into Holy Week, and the celebration of Easter.

This week, I’m examining a different aspect to the justification which takes place in the atonement through Jesus Christ. Often one sided as the justification of man, Barth in §61, under the heading of The Justification of Man, begins first with the justification of God. In short, he argues that the “backbone of the event of justification” is the justification of God Himself, that He is just in Himself and in the right. Here, then, are some insightful quotes from Barth and reflections on the subject. Enjoy!

(As before, all quotes are from the Hendrickson Publishers 2010 Edition. All bold texts are my emphasis.)

The Justification of God

The God who is present and active in the justification of man, and therefore as the gracious God, has right and is in the right. Not subject to any alien law, but Himself is the origin and basis and revealer of all true law, He is just in Himself. This is the backbone of the event of justification. (pp.530-1)

God Himself is law. (p. 529) And God is in complete harmony with Himself. On the cross God proves this, revealing this fact in stark contrast with our inconsistency, our pride, and our sin. God shows Himself to be just in and through Jesus Christ. He shows Himself to be faithful despite our unfaithfulness.

In the revelation and efficacy of the grace of Jesus Christ proclaimed in the Gospel what comes first is not the justification of the believer in Jesus Christ but the basis of it—that God shows Himself to be just. […] The faithfulness of God Himself, cannot be destroyed by any unfaithfulness of man. […] In the first instance God affirms Himself in this action, that in it He lives His own divine life in His unity as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. But in it He also maintains Himself as the God of man, as the One who has bound Himself to man from all eternity, as the One who has elected Himself for man and man for Himself. (p. 532)

The grace God shown in justification is not an alien grace to the nature of God’s eternal being. God is gracious in Himself from before all time. He does not become gracious for our sakes. And if this were true, God would remain untrustworthy. If God only becomes gracious He may also someday become ungracious. Which leaves us with no assurance of God’s goodness or favor towards us, thus voiding the very Word spoken in Jesus Christ. So we must say this is true, that God is gracious in Himself from before all time. And Barth here seems to be affirming the importance of this. God first justifies Himself as the God who is faithful in Himself, and “in the exercise of His Godhead” He, for the sake of all flesh, became flesh. (pp. 532-3) That is, in other words, as God is in Himself He is towards us, He is faithful because He is faithful to Himself, and He is gracious because He is the gracious One.

And as this faithful One, God has taken our condition serious as His own. As Barth writes of mans rebellion, “He takes it so seriously that He encounters it in His own person.” (p. 533) We cannot undo this faithfulness. And in spite of our unfaithfulness to God, God remains wholly determined to us. We cannot disrupt this “self-determination of God”. (p. 534) Mankind belongs to God, as God has determined mankind for Himself and Himself for mankind. We cannot escape this determination, we cannot escape God’s being for us. This is the justification God makes of Himself, that He will not abandon His eternal will for mankind.

In a fascinating paragraph, Barth takes this justification of God in terms of immutability. Writing:

One thing is certain. It can be true only on the presupposition that God as God is in Himself the living God, that His eternal being of and by Himself has not to be understood as a being which is inactive because of its pure deity, but as a being which is supremely active in a positing of itself which is eternally new. His immutability is not holy immobility and rigidity, a divine death, but the constancy of His faithfulness to Himself continually reaffirming itself in freedom. His unity and uniqueness are not the poverty of an exalted divine isolation, but the richness of the one eternal origin and basis and essence of all fellowship. The fact that according to His revelation God is the triune God means that He is in Himself the living God. (p. 561)

God is immutable not in the sense that God is a static, unmoved mover, but that God is the living God, the God who is in freedom faithful. This God is the basis of all fellowship, as the living God, the Triune God.

It is this God who has justified Himself in Jesus Christ, as our God, as the One who is faithful towards mankind because He is first faithful to Himself. This beautifully reaffirms the Trinitarian life of God as the origin for the good news of Jesus.

Jesus came as a man and died in our place because that is what the Triune God is like. It is the overflow of who God is. This is who God has revealed Himself to be in this justification. He is our God, faithful to mankind, despite all our unfaithfulness. He is the immutable, living, Triune God of grace. He has always been this God, and in Christ He has justified Himself as this God, reaffirming His faithfulness to mankind.

Here’s one final quote to bring this home to the radical love of this Triune God, this God who is faithful to us in Jesus Christ.

God does not merely confront him as God and Lord and Judge, but as such He effectively takes His place at the side of sinful man, indeed, He takes the place of sinful man, representing him against Himself. His eternal Word becomes flesh. He Himself in His Word becomes man. Why? In order that He may not only conduct His own case against all men, but take up and conduct the case of all men, which they themselves cannot conduct, in that process between Him and them. In order that He may be for them what they cannot be for themselves—an active subject and a passive object in that conflict… Not from His own side. Not as God, Lord and Judge. But from their side. As the God, Lord and Judge who is man, servant and judged. In general terms, what has taken place in Jesus Christ is the divine participation in the situation of the man confronted by His right… It is as God identifies Himself with man—His participation and intervention is as direct and complete as that—it is as He becomes a man and as this man the Representative of all men, it is as He makes His own the cause of all men that justification can and does take place. (p. 551)

God is justified in Jesus Christ. God is faithful and gracious in Himself, and therefore He is faithful and gracious to mankind. He is so for us in this way and is so self-determined to be faithful to us that He has taken up our condition as His own. God became a man. He participated in our life; He made our cause His own. And in this He justified Himself as this faithful One.

Like this article? Share it!