Stephen D. Morrison's Blog, page 7

August 16, 2017

“Encountering Reality” by Travis M. Stevick: a Book Review

Book: Encountering Reality: T.F. Torrance on Truth and Human Understanding by Travis M. Stevick (AMAZON LINK)

Book: Encountering Reality: T.F. Torrance on Truth and Human Understanding by Travis M. Stevick (AMAZON LINK)

Publisher: Fortress Press, emerging scholars series (PUBLISHERS LINK)

Overview: Stevick’s book was an interesting read, which engages Torrance’s epistemological developments with contemporary philosophy and science. This was undoubtably the strength of the book, alongside the clear and careful explanation of Torrance’s thought. Though more a book for the specialized, this is still an insightful critical study of Torrance’s central epistemological claims.

I had a different expectation of what I was about to read before I finished Stevick’s Encountering Truth, and to be honest, as excellent as this book was, it fell outside my realm of interest. Stevick did well in engaging Torrance with contemporary epistemology, and his critical appreciation of Torrance is one I can agree with. His conclusions did put words to some of the reservations I’ve had regarding the effectiveness of some of Torrance’s engagement with science. But all things considered this was a carefully written, scholarly study of Torrance’s thought in dialogue with modern epistemology. If this is an interest of yours, then you will likely find it far more captivating than I did.

Stevick’s stated purpose in writing is to

“unpack and critically explore what has been called the ‘fundamental axiom of Torrance’s theology,’ the conviction that we know something authentically only when we know it according to its own nature, what Torrance describes as knowledge that is ‘kata physin.‘” 1

On this level Stevick has certainly succeeded. He unpacks exceptionally well that central axiom, which is so important to Torrance, that what we know must be known in accordance with itself. In a summary of this idea, Torrance writes,

“In any rigorous scientific inquiry you pursue your research in any field in such a way that you seek to let the nature of the field or the nature of the object, as it progressively becomes disclosed through interrogation, control how you know it, how you think about it, how you formulate your knowledge of it, and how you verify that knowledge.” 2

Torrance learns this axiom from Athanasius, who Torrance considers one of the chief influences of his own thought, but also he acknowledges a debt to Kierkegaard and Anselm. Stevick’s unpacking of this notion and its implications is excellent, and on this level the book was a pleasure to read. I especially enjoyed in the first chapter how he connected this axiom with Torrance’s rejection of dualistic thinking.

There is no fault I could credit to Stevick’s book, since most of the individuals he brings Torrance into dialogue with I’ve only barely heard of before. On this level I have nothing to comment in terms of a review. On the aspect of Stevick’s careful explanation of Torrance’s epistemology, from his central axiom, to his rejection of dualism, and his stratification theory of knowledge, I think this is an excellent study. For anyone interested in the ins and outs of Torrance’s epistemological conclusions, this would be a great book to pick up.

My thanks to Fortress Press for a digital copy of this book for review. I was under no obligation to offer a positive review, and have presented my honest reflection on this work.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Kindle loc., 40 ↩Torrance, Preaching Christ Today, 45 ↩August 11, 2017

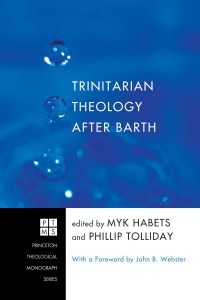

Trinitarian Theology after Barth: a Review

Book: Trinitarian Theology after Barth (Princeton Theological Monograph) ed. by Myk Habets and Phillip Tolliday, with a foreword by John Webster (AMAZON LINK)

Book: Trinitarian Theology after Barth (Princeton Theological Monograph) ed. by Myk Habets and Phillip Tolliday, with a foreword by John Webster (AMAZON LINK)

Publisher: Pickwick Publications (an imprint of Wipf & Stock Publishers), included in the Princeton Theological Monograph Series #148 (PUBLISHER LINK)

Overview: Like any collection of essays, there will always be those essays that hit a home run, those that intrigue great interest, and sadly sometimes also those that fall flat. In this collection there were far more home-runs and sparks of intrigue than in most of the collections I’ve read, and for that reason alone this is an excellent and thought-provoking book well worth your time. It will be of special interest for those wanting to study Barth’s Trinitarian theology, and particularly to examine the diverse streams of thought of those who have more or less followed after his work.

Without a doubt the most striking essays in this collection came from Bruce McCormack and Benjamin Myers, at least for me anyways. I have been loosely familiar with the so-called “companion controversy” or the “Barth-wars”, as some have exaggeratedly dubbed it. This is the debate over the ramifications of Barth’s doctrine of God following his radical revision to the doctrine of election. McCormack has pioneered this debate with his thesis, and up until now I have remained mostly indifferent to the outcome. But after reading McCormack’s essay I am all the more intrigued by what he has to say. I am not saying I am convinced quite yet, because what he argues is radical, but I am more interested now than I had been before. And most of all, I am far more informed as to what McCormack is actually saying, which is surprisingly much different from what I was told he is saying.

The expertise and elegance of McCormack’s essay, aptly followed by Myers’ essay, struck a chord with me. Accordingly, in this review I will focus on the chief argument of these two essays, and examine various quotations from each.

But I would be in the wrong not to at least mention a few of the many other excellent essays I enjoyed from this volume.

Myk Hybets’ essay on the filioque clause, which relies upon T.F. Torrance’s work heavily, was simply excellent. A solid essay, and I am grateful for it as I have begun working on my own book about Torrance. (T.F. Torrance in Plain English, forthcoming.) Particularly I am thankful to Hybets for drawing attention to a theologian unknown to me up until now: Thomas Weinandy. Hybets praises Weinandy’s book, The Father’s Spirit of Sonship, as a profound way forward after both Barth and Torrance. I plan on picking up a copy of Weinandy’s book soon. (You can purchase your own by clicking here.)

Other essays that I enjoyed were Molnar’s essay highlighting the role of the Holy Spirit in knowing the Triune God in the work of Barth and Torrance. Often Barth is under-appreciated for his subtle attention to the Holy Spirit, but Molnar does a great job highlighting the importance for Barth of the Spirit’s role.

Davidson’s essay and Rae’s essay were also noteworthy. Rae’s especially brought out several interesting points regarding the “spatiality of God”, something that I recall intrigued me greatly about Barth’s work in CD II/1. Tolliday’s essay was also insightful, regarding the issue of subordination in Barth’s doctrine of the Trinity.

Another home-run was Andrew Nicol’s essay “Why Do Humans Die?”, which examines the role of death in Barth and Robert Jenson’s thought. I am not tremendously familiar with Jenson’s work, but this was an interesting look into his understanding in dialogue with Barth.

And finally, Haydn D. Nelson’s essay on divine immutability and impassibility was of great interest. I feared Moltmann would be only negatively engaged with in this book, and I was right to assume he would be. But this was a fair and insightful treatment of Moltmann’s work (though indirectly), which offers some possible steps forward into a more nuanced understanding of impassibility and immutability.

These were my favorite essays, not because I agreed with them completely, but because they were the most interesting to read. Some may likely find a few of the other essays to be more stimulating, such as Link-Wieczorek’s work on inter-religious dialogue or Moyse’s on biomedical ethics. But I can only say which essays I enjoyed the most.

But as I’ve said, in this review I want to briefly examine McCormack’s essay and Myers’ essay since they were the most profound in my eyes.

McCormack’s essay

McCormack’s essay begins with a story. He once asked T.F. Torrance what the difference between his doctrine of the Trinity and Barth’s was. Interestingly, Torrance replies that “his own doctrine owed a great debt to Gregory Nazianzen while Barth’s doctrine was ‘Basilian.'” (87) This is something McCormack unpacks towards the end of his essay.

The primary idea McCormack is after is to “reconstruct Barth’s doctrine in the light of his later Christology”. McCormack points to a fundamental change from CD I/1 to IV/1 in Barth’s Trinitarian thought. He essentially claims that Barth has two doctrines of the Trinity: the first from CD I/1 is based on the statement, “God reveals Himself as the Lord”, and the second from CD IV/1 is based on a more concrete Christology. McCormack writes that the question occupying Barth’s thought in CD I/1 was, “How can God enter into the sphere of human knowing without surrendering himself to epistemic control, thereby setting aside his sovereign freedom?” (105) However, that question significantly changes in CD IV/1 into a “deeply ontological” question “of the Godness of God in his self-revelation”. Essential, Barth now is asking, “How can God live a human life, suffer, and die—without undergoing change on the level of his being?”

A key quotation for this that McCormack points out happens to be one of my favorite statements from CD IV,

“Our concept of God is too narrow, too arbitrary, too human, all too human. Who God is and what it means to be divine is something we have to learn where God has revealed Himself, and thereby, His nature, the essence of the divine. And when He reveals Himself in Jesus Christ as the God who does such things, then it must lie far from us to wish to be wiser than he and to maintain that such things stand in contradiction to the divine essence.” (Karl Barth, CD IV/1, 186; emphasis McCormack)

McCormack notes, “Barth’s solution to the ontological form of his central question is clear: suffering and death do not change God because they are essential to him.” (105) This is a difficult statement to unpack, but McCormack does well at explaining the significant moves Barth is making to reach this conclusion.

Essentially, McCormack argues that Barth’s doctrine of the Trinity in CD IV/1 is more “concrete” and therefore less “abstract” than his earlier treatment, since here Barth takes as the basis of his doctrine the concrete history of Jesus Christ and not merely the statement that “God reveals Himself as the Lord” (which has been often criticized). McCormack explains, in a summary statement of sorts:

“Taking a step back, it has to be said that the basic structure of Barth’s doctrine of the Trinity remains unchanged in my reconstruction. One Subject in three modes of being—that remains Barth’s view. But materially, the doctrine has changed as a consequence of the fact that Barth’s derivation of the doctrine has changed. He no longer equates the divine essence with hiddenness, but with the concrete Subject who is completely given in each of his three modes of being. I call this Subject ‘concrete’ because nothing is said about him beyond that which is made possible by his self-revelation in Jesus Christ, and everything that is said about him is authorized by the historical event.” (111)

And at the core of this argument is the thesis that God’s eternal being was before all time what God became in the history of Jesus Christ. McCormack writes,

“The immanent Trinity is already, in eternity, what it will become in time. If obedience is proper to God, if it is a personal property of the triune God in his second mode of God, then there is no difference in content between the immanent and the economic Trinity. The immanent Trinity is the economic Trinity and vice versa. … If the incarnation is not a new event when it takes place in time, this is because the condition of its possibility is already found in an eternal act of willed receptivity vis-a-vis the humanity to be assumed. …To put it this way is to suggest that there is no such thing as an ‘eternal Son’ in the abstract. The ‘eternal Son’ has a name and his name is Jesus Christ.” (111)

This is all rather complex and difficult to conceive, and McCormack’s essay does a far better job than this summary has does so far at explaining his point. However, there is a helpful remark McCormack makes that brings this all into focus. McCormack writes that Barth is here at once Cappadocian and modern:

“The Cappadocian element consists in the recognition that God is triune because the Father has freely willed to be so. The modern element consists in the integration of the covenant into the eternal act in which the Father freely constitutes himself as triune.” (112-3)

And finally, McCormack summarizes his thinking so far:

“The train of thought I have developed to this point may be summarized as follows. An act of self-determination that makes humility and obedience to be essential to God is clearly and freely willed activity that is constitutive of what and who God is. But now, if the act of self-determination is an act whose consequences ‘become’ essential to God, then we are confronted with two possibilities. Either the divine essence was constituted in one way before this ‘eternal’ act and in another way after it or this act is ontologically primordial in the sense that there is nothing ‘before’ it—no constitution of the divine essence that is other than or different from what the divine essence is made to be in the act itself.” (113)

The former necessitates a rejection of divine constancy, and the latter necessitates a change in divine ontology. McCormack’s argument is that Barth takes the latter path over the former, and therefore we come full circle. McCormack sees the grounds for a second doctrine of the Trinity in Barth’s decision, a revision that, if Barth had completed CD V, he thinks Barth would have likely drawn out himself.

And this is where the so-called “Barth-wars” have come from. McCormack argues that “election and triunity are given together in one and the same eternal event.” Clarifying further that, “Neither has ontological priority over the other. But election has a logical priority over Trinity—because decision has a logical priority over being.” (115)

This second remark is an extremely helpful one. Some have caricatured McCormak’s argument vs. Hunsinger’s as “election first then Trinity” vs. “Trinity first then election”, but McCormack is clearly arguing more for “both” at once, with only a logical priority given to election. This clarification doesn’t make his argument correct by default, but it does shed light on what exactly McCormack is after.

As I’ve said initially, I am not agreeing with McCormack’s conclusion here anymore than I am agreeing with Hungsinger’s (even though that was my natural inclination before reading McCormack’s argument). I am simply interested in clarifying what it is that McCormack is actually arguing.

I am unable to adequately weigh in on such a complex issue, but I am beginning to understand it better, following my reading of McCormack’s essay. I hope this limited summary has encouraged you to do the same.

Myers’ essay

I want to quote some highlights from Myers’ essay, which works well as a companion to McCormack’s. Myers more directly engages this thesis with the theology of Jürgen Moltmann, which was fascinating for me to read. Myers essential thinks that Barth is more radical in his ontology than Moltmann in his famous book, The Crucified God.

Myers writes, “election is Barth’s alternative to a Moltmannian theology of the cross.” (131) Calling this a “more metaphysically radical than anything Moltmann achieved in The Crucified God…” (131) Those interested in Moltmann and Barth alike will undoubtably find this essay to be of great interest.

But I want to end this review with a few clarifying statements from Myers’ essay that I found helpful for understanding McCormack’s radical thesis. Myers writes,

“God has no being apart from what happens in the human Jesus. The idea of a ‘divine being’ existing outside relation to Jesus is, Barth thinks, the very essence of idolatry. God’s being as God is constituted by God’s self-determined relation to the human Jesus. Simply put, this means that what happens in Jesus really matters for God.” (130)

“God’s deity, then, is not some entity which calmly precedes (in order to be disclosed in) the history of Jesus. God’s deity, rather, consists in God’s determination to be the God whose own internal life takes on the form of humiliation, lowliness, and crucifixion. God elects the cross of Jesus as the site of God’s own being. The crucified Jesus is the content of God’s decision about who God will be from all eternity.” (130)

“For Barth, then, God’s triunity is always already a cruciform triunity. God elects the death of Jesus as the shape of God’s own life. God ‘is not untrue to himself but true to himself in this condescension.’ The crucified Christ is the perfect—the beautiful and terrible—realization of what it means for God to be God. The wound of the cross is a real wound; but this wound is already at the heart of that eternal communion, that love which is always in motion between the Father and the Son in the Holy Spirit.” (132)

Myers then argues against the Logos Asarkos and dialogues with Molnar’s critique of McCormack’s thesis. In a summary of the three possibilities after Barth, Myers writes,

“In contemporary considerations of the relation between the human Jesus and the eternal being of God, we are, I think, faced with three main alternatives: a mutable being who undergoes change as a result of what happens in Jesus (Moltmann); an indeterminate and unknowable divine being who lies behind the election of Jesus (Molnar); or a divine being who is both knowable and immutable, since it is always already determined towards the history of Jesus (McCormack). …I have argued that Barth’s ‘second’ doctrine of the Trinity points to this third option, a God whose being is eternally shaped by what happens in Jesus’ history, and by a self-determined movement towards that history. …

Or to put it more succinctly: God is eternally self-consistent because Jesus Christ is not only the elected human but also the electing God. Jesus is God’s self-consistencey, God’s way of being God.” (135-6)

Conclusion

This review has been somewhat overpowered by the thesis presented by McCormack and Myers, in very much the same way that the book, for me anyways, was determined by these two essays. I enjoyed reading it tremendously, and I hope I have not under-valued the great essays that exist alongside these two.

Fundamentally, I neither wish to argue for or against McCormack’s thesis. Instead, I found myself surprised by how much I initially misunderstood it! I would hope that those interested in McCormack’s work would not hastily judge his thesis as wrong just because it is complex, difficult, and quite radical. This volume would be a helpful entry-level study into exactly what McCormack is after.

Primarily, however, this was a great collection of essays well worth reading, which obviously has been the cause of much thought for me personally. I recommend reading it if you are interested in furthering your understanding of Barth’s thought and especially of the contemporary status of Trinitarian theology following his profound theological career.

My thanks to Wipf & Stock for a digital copy of this book for review. I was under no obligation to offer a positive review, and have presented my honest reflection on this work.

Like this article? Share it!

June 26, 2017

“Trinitarian Grace and Participation” by Geordie W Ziegler: a Review

Book: Trinitarian Grace and Participation: An Entry into the Theology of T. F. Torrance by Geordie W Ziegler (Amazon link)

Book: Trinitarian Grace and Participation: An Entry into the Theology of T. F. Torrance by Geordie W Ziegler (Amazon link)

Publisher: Fortress Press (Emerging Scholars series), 2017 (Publishers link)

Overview: Ziegler’s book is quite an achievement, with clarity and precision he embarks on the difficult task of exploring Thomas F. Torrance’s complex thought. The book emphasizes what Ziegler calls “a deeper strata of Torrance’s theology: his theology of grace, in which all other doctrines find their interior logic.” 1 This is a highly commendable and insightful reading of Torrance, recommended for anyone interested in his work.

I enjoyed this book from Georgie W Ziegler. I’ve read a fair amount of Torrance’s work, though I’m only beginning to explore the ever-expanding collection of secondary literature on Torrance. Ziegler’s book stands out from what I have read so far.

Colyer’s classic, How to Read T. F. Torrance, for example, is quite dull in comparison. Which is not to say that Colyer’s book is worse or in any way inaccurate—it is a very helpful book—but I think Ziegler captures the heart of Torrance’s theology better by emphasizing grace and participation as central concepts in his thought. His clarity and joy kept me engaged, shedding profound light on some of Torrance’s more complex subjects.

By emphasizing grace and participation Ziegler kept central what has always attracted me the most about Torrance’s theology: the profoundly evangelical character of everything he writes. Torrance is an excellent scholar, he’s a brilliantly constructive theologian, and his engagement with science is fascinating; but more than all that Torrance was a pastor and an evangelist. Even his engagement with science, Torrance once remarked, falls within the context of being an evangelists to the scientists. Torrance is a true evangelical theologian.

Furthermore, by focusing on grace and participation Ziegler is able to shed new light on some of Torrance’s difficult concepts (by placing them within their proper content). One instance that comes to mind is the insightful discussion of the anhypostasia and enhypostasia (the an/en couplet) in Torrance’s thought, and how it relates the human agency. Ziegler writes,

In Torrance’s view, the an/en couplet opens up conceptual space for a dynamic way of describing divine and human agency in Christ that illuminates the key features of the motion of Grace, which Chalcedon’s negative assertions fail to capture. While the person of the Son remains the single hypostasis or agent of the God-human, the human Jesus is no mere instrument in the hand of God, but a full human person with human body, mind, reason, will and soul. For Torrance, the doctrine of two wills (2nd Council of Constantinople [680AD]) is a critical move which discloses the ontological nature (as well as the nature of the ontology) at the inner heart of the atonement. Were Christ to only have one will there would be no historical (lived) means for the divine Word to reorient that will. Here in the will of Jesus Christ, the divine will and the human will coexist without confusion or separation and in that onto-relational coexistence, the will of estranged man is bent back into oneness with the divine will through the sanctifying obedience of Christ. Through the concept of the an/en hypostasia combined with the doctrine of two wills in the Person of Christ, Torrance is able to hold incarnation and atonement together such that atonement takes place within the person of Christ himself as he personally mediates the two natures.

Combining the an/en with the biblical material, the pattern can be expressed in the following way: as triune Grace is always both downward and two-fold and always both anhypostatic and enhypostatic, so also is the life of Jesus—always simultaneously, the Son sent from the Father in the Spirit and the Son in the Spirit offering his life to the Father. 2

This helps clarifies an important phrase Torrance often repeated, that, “All of grace does not mean nothing of man [but, rather,] all of grace means all of man.“ 3

Discussions about God’s grace often have difficulty answering the question of human agency. Far more than perhaps any theologian I’m familiar with, Torrance’s emphasis on the vicarious humanity of Christ and his nuanced approached to the anhypostasia and enhypostasia is a profoundly helpful response to the question of grace and human agency. Ziegler’s discussion of this aspect of Torrance’s thought is very insightful and helped me understand this couplet better than I had before.

In conclusion, this book is an excellent study of Torrance’s thought, very insightful, profound, and clear. However, I doubt it works as an introductory book. I do not know if this was Ziegler’s intention, but from the subtitle it seems to me that Ziegler hoped his book would be readily accessible to the average reader. It wouldn’t be impossible for an amateur to read it, no doubt, but I think it would be quite difficult nonetheless. Some basis in Torrance’s thought will be helpful before reading. Although, that does not deter from the excellent of his book. I recommended it to anyone interested in Torrance.

My thanks to Fortress Press for a digital copy of this book for review. I was under no obligation to offer a positive review, and have presented my honest reflection on this work.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Kindle loc. 200 ↩Kindle loc., 2097-2106 ↩Mediation of Christ, xii; quoted by Ziegler, Kindle Loc. 6855 ↩June 22, 2017

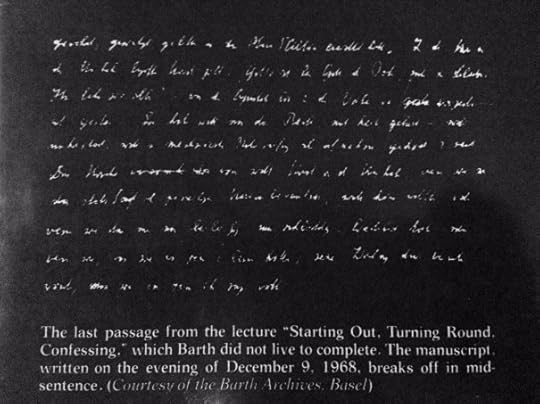

The Final Written Words of Karl Barth

From the back cover of “Final Testimonies” by Karl Barth.

In my book, Karl Barth in Plain English, I wrote the following:

Karl Barth died in his sleep on the morning of December 10 [1968], having spent the evening listening to Mozart and writing yet another theology lecture.

Barth left that lecture unfinished. His last written words abruptly end mid-sentence. What could be more testimonial to Barth’s career than this unfinished sentence? He remained engaged his entire life, even in his later years, with so many social and political issues right alongside the many theological issues of his time. His work remains unfinished, but breathtaking still, like Gaudi’s majestic Sagrada Família in Barcelona. It is this enduring faithfulness and diligence to the Word of God which makes Barth one of the most productive and inspiring theologians who ever lived. 1

I wanted to share that unfinished sentence, Barth’s final written words, for anyone who might be interested in it.

Barth was invited to attend an ecumenical week of prayer in Zurich, and to give a special address to a group of Reformed and Roman Catholic believers. It was this address that Barth worked on before his death. He gave it the title, “Starting Out, Turning Round, Confessing”.

It is only about eight pages long and remains in an unrevised state; but regardless, even in this brief sketch Barth was characteristically focused on Jesus Christ, writing, “He, Jesus Christ, is the old and is also the new. He it is who comes [to the church] and to whom the church goes, but goes to him as him who was. It is to him that it turns in its conversation.” 2

In the final paragraph, Barth seems to have in mind the need for the church to listen attentively to the fathers who have gone before us. Busch rightly notes in the epilogue that Barth himself should be counted among those we should listen to attentively. But without further ado, here are the final written words of Karl Barth (brackets contain Busch’s corrections):

In the church that is in the process of turning round the saying is true that “God is not the God of the dead but of the living.” “All live to him,” from the apostles to the earlier and later fathers. They have not only the right [but also the relevance] to be heard today, not uncritically, not in automatic subjection, but still attentively. The church would not be the church in conversion if, proud and content with [?] its sense of the present hour, it would not listen to them, or would do so only occasionally, loosely, and carelessly, or if it were to rob what it has to learn from them of all its effect by [accepting] what they want to say to it . . . 3

Busch thinks Barth’s sentence might have been finished like this: “…by accepting what they want to say to it, perhaps with much reverence, but only as a statement of the insights of their own day.” 4

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

Page 12 ↩Final Testimonies, 59; LINK ↩Ibid., 60 ↩Ibid., 63 ↩June 16, 2017

Karl Barth in Plain English – Facebook Live Q&A

Like this article? Share it!

June 6, 2017

“Karl Barth in Plain English” – Table of Contents

Karl Barth in Plain English is now available on Amazon Kindle, and soon in paperback format.

I’m incredibly excited for this book, which has been the product of years of reading and studying Karl Barth. In this book I hope to present a clear and concise overview of Barth’s major ideas; written for beginners, by a beginner.

The book resolves around the eight major ideas I’ve chosen to focus on from Barth’s thought. In between the major chapters on these ideas, I present “Sidebar” chapters and “Sermon” chapters. The sidebar chapters are the clarify a difficult aspect of Barth’s thought, or to engage him with contemporary issues. The sermon chapters include quotes from Barth’s sermons, which I have found helpful in understanding his theology.

Join me on Tuesday, June 13th for a Facebook Live celebration of the book, where I will answer questions, read excerpts, and discuss writing the book!

Here then is the table of contents for my new book:

Introduction

Biography

The Structure of Barth’s Church Dogmatics

CHAPTER 1: Nein! to Natural Theology

SIDEBAR: God’s Humiliation and Natural Theology

SERMON: The Great “But”

CHAPTER 2: The Triune God of Revelation

SERMON: God Without Jesus

SIDEBAR: Mode of Being

CHAPTER 3: The Threefold Word of God

SIDEBAR: Biblical Inerrancy

SERMON: They Bear Witness to Me

CHAPTER 4: There is No Hidden God Behind the Back of Jesus Christ

SIDEBAR: The One Who Loves in Freedom

SIDEBAR: No Hidden Will of God

CHAPTER 5: The God of Election

SERMON: Preaching Election

SIDEBAR: Universalism

CHAPTER 6: Creation and the Covenant

SIDEBAR: Non-Historical History

SERMON: The Fear of the Lord

CHAPTER 7: Reconciliation

SIDEBAR: Limited Atonement and Calvin’s “Horrible Decree”

SERMON: The Divine Life

SERMON: Have You Heard the News?

CHAPTER 8: The Church and Ethics

SERMON: You May

God With Us and For Us: a Closing Reflection

Books to Continue Your Study

Like this article? Share it!

May 22, 2017

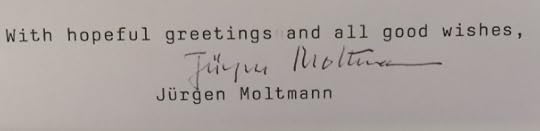

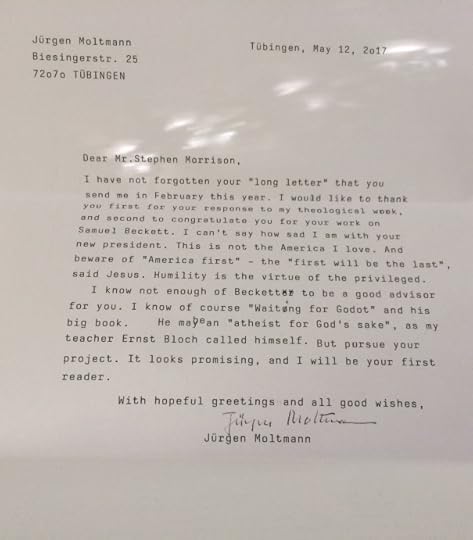

“Beware of ‘America First'” – Jürgen Moltmann on Donald Trump’s America

I have just shared about Jürgen Moltmann’s letter to me, which you can read here in its entirety. But I wanted to highlight a moving aspect of that letter, namely, Moltmann’s response to my question about Donald Trump as the new president of the United States.

I have just shared about Jürgen Moltmann’s letter to me, which you can read here in its entirety. But I wanted to highlight a moving aspect of that letter, namely, Moltmann’s response to my question about Donald Trump as the new president of the United States.

I wrote my letter in February, during the time when Trump was attempting to ban Muslim’s and block Syrian refugees from entering the country. This was (thankfully!) blocked and deemed unconstitutional after protests and political opposition arose all around the country. But my concerns regarding the current president have not ceased, and Moltmann’s response beautifully summarizes all of the reservations which I have felt regarding our current president. In my opinion, Donald Trump’s America is the antithesis of the best principles America was built on, exemplified clearly in the poem inscribed on the Statue of Liberty, “The New Colossus”: “Give me your tired, your poor, / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, / The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. / Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, / I lift my lamp beside the golden door!” But it is not only as an American that I am hesitant about Trump, but also as a Christian; I can’t help but think Trump’s America follows the path of a violent empire, which is not the way of the kingdom of God.

Professor Moltmann’s profound response is deeply moving:

“I can’t say how sad I am with your new president. This is not the America I love. And beware of ‘America first’ — the ‘first will be the last’, said Jesus. Humility is the virtue of the privileged.”

Like this article? Share it!

Jürgen Moltmann’s Letter

I was honored to receive a letter today from one of my theological heroes, the great German theologian of hope herr professor Jürgen Moltmann. I wrote professor Moltmann in February, and had almost given up “hope” that I’d ever hear a response. This was before checking my mailbox today to find this greatly-anticipated letter from Germany, much to my excitement!

I wrote Moltmann primarily to thank him for his books and for the profound impact they have had on my faith and theology. Readers of my articles and books will know that I consider professor Moltmann to be one of my three favorite theologians (with Barth and Torrance). I consider him, without any hesitation, the greatest theologian alive today. His work has had a profound impact on me ever since reading his masterpiece, The Crucified God, almost four years ago. In 2014 I wrote a short (if slightly premature) book that wrestles with Moltmann’s “theodicy”, entitled Where Was God? [LINK]. I am currently preparing to research and write a more fully-fleshed book on Moltmann as a part of my “Theology in Plain English” series. I also plan to write a book on Moltmann and Samuel Beckett, one of my favorite literary authors. So it goes without saying, I am deeply grateful for the theology of Jürgen Moltmann, and I was honored to receive this personal letter!

I asked Moltmann two questions after profusely thanking him for his theological work. First, I asked about the current president of the United States, Donald Trump. Like many other Americans I am profoundly disturbed with the president; I find many of his policies to be the very antithesis of the way of Jesus Christ. It shouldn’t be a surprise to those familiar with Moltmann to learn he also responded with sadness about our president, writing, “I can’t say how sad I am with your new president.” Second, I asked Moltmann if he has any comments about Samuel Beckett, and I mentioned my interest in placing his theology into dialogue with Beckett’s literary project. To this Moltmann said he is mostly unfamiliar with Beckett, but encouraged me to pursue the project.

My thanks again to professor Moltmann for kindly responding to my letter!

Here is his response in its entirety:

Like this article? Share it!

May 17, 2017

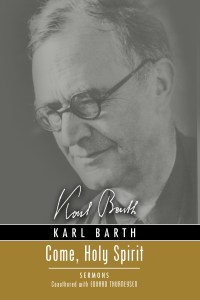

Come, Holy Spirit: Sermons (by Karl Barth), a Review

Book: Come, Holy Spirit: Sermons by Karl Barth and Eduard Thurneysen (Amazon link)

Book: Come, Holy Spirit: Sermons by Karl Barth and Eduard Thurneysen (Amazon link)

Publisher: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2009 (Publisher link)

I have a soft spot for reading Karl Barth’s sermons. This is now the fourth collection I’ve read; and while I can’t say it was my favorite (Deliverance to the Captives earns that honor), this book is a fascinating and insightful look into Barth’s early preaching and thinking.

There is an attractive liveliness in Barth’s early work, and this collection is no exception. The translators introduction highlights this well: “These sermons simply proclaim God, but not as a static absolute far removed from the world, not as an immanent essence entangled with the world; they preach the good news of God ‘in action,’ of a living person who is wholly other than the world and yet Creator, Upholder of the universe, Savior and Sanctifier of men…” 1

These sermons were preached shortly after The Epistle to the Romans had its famously devastating effect upon the theological world. It should be no surprise then to learn that these sermons echo many of Barth’s famous remarks in Romans, such as the wholly-otherness of God and the “infinite qualitative distinction” between God and mankind.

This collection, we could say, is the “preached edition” of Barth’s Romans; many of those same themes are here preached in a pastoral manner.

Therefore, we read statements which devastate all our attempts to know God with ourselves at the center of that knowledge, such as this:

It is possible that whenever we utter the word ‘God’ we think of something high, great and beautiful, as a goal or ideal which we have set for ourselves. But fundamentally that would be a weighing of ourselves by ourselves; we ourselves would be our own judges and emancipate or condemn ourselves. But God dwells in a light which no man can approach. Even the highest which we think about Him when measured by His true self is still an illusion. He himself is God. He alone knows it. 2

Barth’s theology is best understood within the context Barth wanted it to be understood in, and in this case that is the context of preaching. I think it would be of great benefit for new readers of Barth’s Romans to also pick up this volume to read alongside it; here Barth the preacher is on full display.

Yet this collection is also chiefly an inspiring set of sermons, which may be read devotionally. There is a pastoral element to each sermon that makes them more than just theology, though they are certainly theological, but go beyond theology into the attempt to proclaim the Word of God.

Here is one of my favorite quotes which highlights this, from the sermon “Good Friday”:

He, too, is in the midst of our misery! Yes, He, too! ‘My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?’ We know this question, do we not? He, too, was pressed, thronged by all sorts of ghosts which press about us. He, too, was in our state of restlessness. He, too, did not know the way out. … He, too, was in fear and trembling upon a way where at every step the impenetrable darkness beclouded Him. We are not alone; He, too, is there. Is there an uncertainty, a question, a doubt in you that is not also in Christ? He, too, is with us in death, but the living one in the midst of death. In His uncertainty there is certainty, assurance in His doubt, an answer in His question. 3

Summary: Karl Barth’s Come, Holy Spirit is an insight collection of sermons which one might read in connection with The Epistle to the Romans, but also as a devotional, pastoral collection for personal edification.

My thanks to Wipf and Stock Publishers for a digital copy of this book for review. I was under no obligation to offer a positive review, and have presented my honest reflection on this work.

Like this article? Share it!

Notes:

George W. Richards, Kindle location 60 ↩Kindle location, 364 ↩Kindle location, 1687 ↩May 13, 2017

God is Love in Himself (Karl Barth CD I/2)

Here’s a wonderful little quote from Karl Barth; enjoy!

“We will now try to give the briefest possible outline of what the love of God is which is the real basis of our love to God, determining its character. One thing is certain, that according to Holy Scripture it has nothing to do with mere sentiment, opinion or feeling. On the contrary, it consists in a definite being, relationship and action. God is love in Himself. Being loved by Him we can, as it were, look into His ‘heart.’ The fact that He loves us means that we can know Him as He is. This is all true. But if this picture-language of ‘the heart of God’ is to have any validity, it can refer only to the being of God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. It reminds us that God’s love for us is an overwhelming, overflowing, free love. It speaks to us of the miracle of this love. We cannot say anything higher or better of the ‘inwardness of God’ than that God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and therefore that He is love in Himself without and before loving us, and without being forced to love us. And we can say this only in the light of the ‘outwardness’ of God to us, the occurrence of His revelation. It is from this that we have to learn what is the real nature of the love of God for us.”

(CD I/2, 377)

Like this article? Share it!