Rick Wayne's Blog, page 56

January 25, 2019

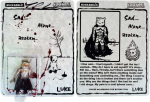

(Art) The Figments & Tales of Hannah Christenson

[image error]

Fantasy illustrator Hannah Christenson, known as Nafah, captures the epic whimsy of great sagas and fairy tales. Each of her single images seems to contain, like a hologram, the full story of the characters portrayed.

Find more by the artist on her DeviantArt page.

January 24, 2019

The Devill playd at Chesse with mee, and yeelding a pawn...

[image error]

The Devill playd at Chesse with mee, and yeelding a pawne, thought to gaine a Queen of me, taking advantage of my honest endeavours; and whilst I labour’d to raise the structure of my reason, hee striv’d to undermine the edifice of my faith.

–Thomas Browne

art by Menton J. Matthews

January 23, 2019

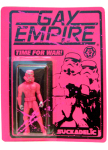

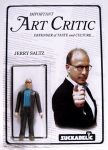

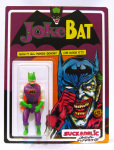

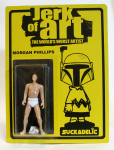

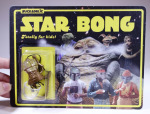

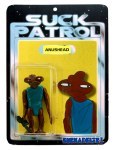

(Art) The Sick, Sick Toys of the Sucklord

[image error]

The Sucklord (born Morgan Phillips circa 1969) is a New York pop artist. He manufactures unlicensed action figures and toys through his company, Suckadelic. has been a long-time fan of Star Wars and Star Wars merchandise and has been profiled for his own versions of Star Wars collectibles. He contributed to series five and six of Topps’ Star Wars Galaxy trading cards and produced three series of his own Suckpax cards. [Wikipedia]

The Star Bong has to be my favorite.

January 22, 2019

(Fiction) That’s When I Saw the Stag

[image error]

in this selection, the narrator is an 8-year-old boy

The day Mr. A. Tranjay came was the same day I saw the stag. That’s what they’re called. I looked it up. A male deer with antlers. It was in the hollow. I was looking for a place to hide the raven’s collection. I had put it all in a white plastic bag I got at the convenience store on Newcombe Street. The twine and the little twirly shell and everything. Everything except the Frisbee ring, which I think my dad threw away. I ate a chocolate bar and walked to the clearing in the middle of the hollow. I could hear the big freeway in the distance and the rustle of the leaves.

I stopped at the ring of downed trees, like a deer blind, and stared at the little flat triangular opening near the ground. It was pitch black. There was a room down there, I think. Underground. Inside the stone foundation was a bunch of fallen branches on top of a long piece of sheet metal. It was all rusted and reddish-brown. It had collapsed and left only the little opening. It was big enough for me but I don’t think my dad could get in. So that was a good place to hide it. No one would find it on accident and take it away. I tossed the bag into the hole without putting my hand in and ran back to my house. The trees rose up like giants on stilts. I had seen stilts at my school. A show came and we got out of class and everyone went to the auditorium. Men and women were on stilts and they did tricks.

That’s when I saw the stag. It was dead. There were only bones. I had seen a cow skull before but not a whole animal skeleton. I didn’t remember ever seeing it in the hollow. I saw the rib cage first. It was propped against a tree. It looked like it had fallen sideways against the trunk as it died. There were brown leaves all around. They were everywhere. And a few patches of snow. I wondered what killed it. I could see every rib. There were so many, all lined up neat and curving together, protecting the heart that had once beat inside. But now it was empty. A kind of ghostly greenish-white moss hung from its spine into the space between the ribs.

My eyes followed the antlers. I hadn’t noticed them at first because the head and neck were pointed to the ground, so the antlers looked like low branches of the tree, but they weren’t. It was a big rack, like a pile of spears. It was so big. They had some moss, too.

The skull moved. I stepped back and snapped a twig. The antlers rose up—straight up—as the spine bent and lifted the head from the ground. The hanging moss shook. I heard bones click against each other. The stag stood up. It took just a second. I wanted to run, but I couldn’t. I didn’t even want to believe it. But there it was. It was so big, bigger than my dad and my old teacher, Mr. Keany, who used to play basketball. I thought maybe it was going to hurt me, but it didn’t. It just turned to me and stood, like it was expecting me to do something. I was shaking. I was glad I had gone to the bathroom before I went into the hollow so there wasn’t any pee left.

Then it bellowed. It lifted its head and opened its mouth and grunted through bare teeth, like my dad when he wants to get up, but louder, like a big mountain horn. Three huge bellows, head raised, mouth open, one after the next. Like it was calling something. I ran then. I ran home and didn’t stop until I got to my dad. He was making dinner. He asked me what was wrong. He said I looked like something had scared me. He asked me over and over what it was. I think he was scared because I was so scared. He was always worried after “the incident.” That’s what he called it. And the nightmares. I wanted to tell him, but I knew what he’d say. So I sat at the table in my jacket and gloves and had dinner. I was shaking. But then I stopped. We had soup and grilled cheese sandwiches. I didn’t eat the crusts. I don’t like the crusts.

After school the next day, I went to the library. I wondered if the stag had something to do with my secret. And I knew that everything anybody knew was on the internet, and that if anybody knew something, it was there. It was good that our new town was so small and everything was close. Philly was so much bigger. Dad never would have let me go to the library by myself.

After the library, I walked home down Newcombe Street because it went under the big freeway, where all the high school kids got together and did graffiti, and then curved around the hollow to our road. I liked that way because I passed the convenience store which has candy. But that meant I also had to walk past a street where some mean kids sometimes called me names. I could cut through the hollow, but there was a fence that ran along the curb, and it was too big for me to climb. I tried once. We were at the bus stop and they were picking on a kindergartner named Trevor because his teeth were different and he didn’t say his S’s right and I told them to stop so they started making fun of me. Then they made fun of my dad’s eye. But I was happy because after that they left Trevor alone.

I was passing that road when I saw the police cars. Two of them. And an ambulance. They were parked on the street in front of a pale green house with brick on the front. Lights were flashing. A few of the neighbor people were standing around. I walked by and heard them talking. I saw the mom and dad come out of the house. The mom was holding a little girl. She was wearing a pink princess dress like I saw in the toy store once. There was lace at the bottom. And the top was shiny. Her eyes were open but she was dead inside. Gone. Forever, even. I think. The adults were silent. People covered their mouths or shook their heads. But everyone was quiet, like in church or at a funeral, as they put the little girl in the ambulance and drove to the hospital.

I saw her face. I saw her eyes. Black and empty like the little hole in the hollow. And I knew what happened. I had seen that before.

I had to find it. Soon. I thought maybe it would look for Pete the parakeet’s cage. Maybe it thought that was home since it stayed there so long. Pete’s cage was a big square thing with metal wires and an orange plastic bottom. After my secret left, I had set the cage outside the garage facing the hollow. I went right there when I got home, but it was empty. Mr. A. Tranjay was in the garage. He’d turned it into a workshop. It looked like the science room at school, with a microscope and everything. He had a bottle from the lot. It was filled with something black and speckled in stars, like liquid night. There was a knife and a wood block on the work bench. He’d been carving it. It looked like a flute.

I poked my head around the door to see if my secret was curled up in the corner. Mr. A. Tranjay looked sick. He was thin. He looked too thin, like the people on TV who have the cancer. Or AIDS. We learned about that in school, where your body can’t stop you from getting sick.

I thought he might notice me, but he didn’t.

At the library I had found a website that talked about animals and stuff. I had printed some pages and I had them on the kitchen table while my dad made dinner. It sizzled. And it smelled like fish. I don’t like fish. It was dark outside. He had a glass of wine. I must have been scowling because he asked me what I was reading.

“Just some stuff.”

“What kind of stuff?”

“What’s a second sight?” I asked.

“What?” My dad scowled with me. He wiped his hands on the towel over his shoulder and walked over to me. He picked up the pages. He read the title, which was printed in small letters at the top. His eyes moved back and forth when he read because of his lazy eye. “The Port Manteau Spirit Society Guide to Animal Spirits and Totems.” He looked at me. “Where did you get this?”

“From the computer. At the library.”

My dad looked skeptical. He scratched his beard. I knew what that meant.

He flipped to the next page and read. “The Stag stands at the gate between the tangible world and the realm of the Others, which aboriginal peoples have called The Dreaming. As such, it imparts special sensitivity to prophecy and intuition and enhances our innate second sight.” He stopped and read the sentence again to himself. “It often appears at the start of a spiritual or cross-dimensional journey.” He turned to me again. “Do you know what cross-dimensional means?”

I shook my head. But I thought I knew what spiritual was. That was what they wanted you to buy at church.

Dad kept reading. “The Stag is a powerful ward and grants special protection in times of transition. It is a masculine spirit and often conveys confidence or power. Since male deer use their antlers to advertise potency and fertility, antlers were believed to impart magical prowess, grace, and strength and were often worn as crowns by early kings before smelting technology allowed the casting of precious metals. Because they are conduits of growth and energy, they are still used by magicians and witches, both good and evil.

“The Stag is the most ancient of the shamanic totems, appearing in mankind’s earliest cave art, and is associated with death and resurrection—the ultimate cross-dimensional journey—since the antlers are shed each season and regrown in a repetition of the annual cycle celebrated by the deaths-and-resurrections of Osiris, Dionysus, and Christ. Due to its antiquity, the Stag’s appearance is unerringly significant and typically heralds a significant passing.” He stopped at that word. I think he read it again. Passing. “Why are you reading this?”

I shrugged.

My dad rubbed the bridge of his nose with his eyes shut. “I thought we talked about this.”

I looked at the pages with a blank face. I thought maybe if I acted innocent I would be in less trouble. Dad was already upset about the raven’s collection. He knew I hadn’t told the truth. And he was upset I had run home scared the other day and hadn’t said why.

“Didn’t we?”

I didn’t say.

“Ólafur, answer me.”

“Whaaat?”

“Didn’t we talk about this? About ghosts and evil spirits and about how you were going to do what the doctor said and not think about those things and if they came up what were you supposed to do?”

“But this is different. There’s a stag in—”

“Ólafur!” my dad yelled. Then he caught himself. “Son, please answer the question. What were you supposed to do?”

“Tell someone.”

“Tell who?”

“An adult.”

“That’s right. And did you tell an adult about this?”

Of course not.

“I just did,” I argued.

My dad sighed and crinkled the papers and threw them in the trash. Then he smelled his fish burning. “Shit!” He glanced at me. “I mean, crap.”

He poked at the pan with the spatula. There was smoke. And a long silence. He drank from his wine glass.

“Are you done with your homework?”

I shook my head. But that was a lie.

“Then you need to eat and go finish. But we’re not done talking about this.”

I nodded.

After dinner, I sat in my bed near the window to the back yard and pretended to do homework, but really I was just drawing pictures of my secret. I knew that’s what had scared the little girl with the pink dress. I could see her limp arms hanging over her mom’s back. And her eyes. I knew she was so scared the only thing she could do was hide inside herself. Maybe forever. Like my friend Emerald. But I hoped she would come back.

I had to find it. I had to put it back in Pete’s cage.

And now there was a stag.

Dad was worried about me. I knew that’s what dads did and he would feel like he was doing a bad job if he didn’t worry so much. But it made everything so much harder.

It was cold by the window and my breath had covered a small patch of window in fog.

And I saw.

There were marks on my window. They showed up in the fog from my breath. Like finger-smears. Someone had traced a symbol on the glass. It swooped and curled.

I leaned closer and blew again, like my teacher did when she cleaned her glasses. It looked like a sideways hooked cross with a circle at one end. And there was part of another above it. A different one.

I stared at my window. I slid back closer to my pillow.

“Dad!” I called as I walked to my open door. “I finished my homework. I’m gonna take a bath.”

“Okay!” he called back.

It was just the two of us in the house so I had a fancy room with a wood floor and my own bathroom. I had my own bathroom in Philly, too. Sort of. It was in the hall and it was mine but my parents used it too sometimes. And guests. But at our new house it was only for me.

I closed my bedroom door and left the bathroom door open. I tuned on the hot water. I let it run and run. It took longer than I thought for the steam to get to the window. But after a while, a thin fog—a lot more than I could do with my breath—spread from the bottom corner up and over the glass.

There were lots of symbols. Six at least.

I was looking at them when I heard Dad’s footsteps on the stairs.

“Ólafur?” he called.

He must have heard the water running. I hadn’t thought about that. I ran to my bedroom and swung the door open and stripped my clothes as I hopped on one leg to the bathroom. I put the stopper down and climbed in, but there was only enough water to cover my feet.

I was sitting there shivering—Dad said it was a drafty house—as he walked into the bathroom.

He stood in the doorway. “What are you doing?”

“Taking a bath,” I said.

“Why was the water running so long?”

“I forgot.”

“You forgot?”

I nodded. I don’t think he believed me.

“Well, finish up. It’s time for bed.”

He walked toward the bedroom door. Then he stopped. I thought he saw the symbols. He would think I had made them. He would be angry. Because of “the incident.” And the nightmares. And the stag. And everything.

He walked to my bed and then I couldn’t see him. As the hot water came up to my belly button, I saw him walk out with papers in his hand.

He took all my drawings.

rough cut from Song on the Green, the fourth course of my forthcoming full-course occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS.

cover image by Anato Finnstark

Quincunx

“When Samuel Taylor Coleridge praised Sir Thomas Browne for having ‘a brain with a twist,’ he captured one of the central reasons why it remains such a pleasure to read Browne’s prose. His idiosyncratic and often surprising ways of thinking are matched only by the peculiarity of the topics he chooses to think about. Why write a formal treatise on the history of the quincunx in gardening, or the discovery of some ancient urns in a nearby field? Why take the time to ponder and refute the popular belief that diamonds are softened by the blood of goats, or that beavers bite off their testicles to escape hunters, or that Jews naturally stink?

Browne was a great coiner of neologisms, finding English insufficiently expressive for all that he wanted to say. According to The Oxford English Dictionary, he was responsible for introducing more than one hundred words to the language, including the nouns exhaustion, hallucination, and suicide; the verbs compensate, invigorate, and bisect; the adjectives precocious, medical, and literary.

More than his contributions to the OED, Browne is celebrated for the quality of his prose. Samuel Johnson first described Browne’s style at some length, although his assessment leaned more toward criticism than praise. The labyrinthine sentences that Johnson castigated seemed, as the twentieth-century novelist W.G. Sebald would later put it admiringly, like ‘processions or a funeral cortege in their sheer ceremonial lavishness.’ Browne love music, and in a remarkable sentence in Religio Medici he marvels at its power over him: ‘it unties the ligaments of my frame, takes me to pieces, dilates me out of myself.’ “

— from the introduction to the NYRB edition of Browne’s Religio Medici and Urne-Buriall

January 21, 2019

(Art) Albertine & Prostitution

[image error]

Albertine is a novel written in 1886 by Norwegian painter and writer Christian Krohg.

The novel is set in Norway’s capital, Christiania, and deals with the life of the unmarried seamstress Albertine, who is eventually forced into prostitution due to the social system of the time. The book was confiscated shortly after its publication. In 1888 the Supreme Court of Norway upheld the confiscation, and Krohg was sentenced to pay a fine of 100 kr. Krohg also made several paintings based on the “Albertine” motif, including Trett in 1885 and Albertine i politilægens venteværelse in 1887.

The book was published on 20 December 1886, and the next day it was confiscated by the police, following orders from the Minister of Justice. A fierce newspaper feud developed, but the confiscation was upheld by the court, both the City Court and the Supreme Court. A demonstration held outside Prime Minister Johan Sverdrup’s (1884–1889) office in January 1887 gathered 5,000 protesters, largely workers and students. The Prime Minister defended his fellow Minister’s actions and the confiscation, but expressed the view that he would exterminate the problems described in the novel, and within a few years public prostitution was made illegal in the Norwegian capital. [Wikipedia]

January 17, 2019

(Review) No Longer Human

[image error]

A colleague of mine once wondered aloud, after seeing the poster of Kali I had brought from India, how it was anyone could worship such a wholly despicable image.

It seems a fair question on its face. The image is undoubtedly despicable. A wild-haired, bare-breasted goddess, tongue dripping blood, brandishes a man’s severed head along with the blade with which she cut it. Around her neck is a garland of skulls. Her skirt is not of grass but the limbs of her victims, who have fallen dead at her feet.

To be fair, my colleague was not playing at scholarly criticism with his comment, which had no depth. Still, in his consternation, there was an implied distinction — that the image was foreign, certainly, but also barbaric, perhaps even inferior.

But then, what is the crucifix if not a depiction of murder? And not just murder, but gruesome torture. Nails have been driven through a man’s hands and feet. He has been stabbed. Blood weeps from his forehead onto which a crown of thorns has been forced. He is exposed, dangling as naked as Kali, his head bowed in suffering.

The dance of Kali and Christ on the cross are two ends of the same swinging pendulum — suffering and its cause. Through their depictions, we are invited to contemplate both our lot and our escape from it: salvation.

That’s not to say there is no difference. The Christian symbol, especially with its foundation in original sin, seems almost to rebuke. Look what you made him do. Now, don’t you feel terrible?

Kali, on the other hand, dances through no fault of ours. She tramples everyone, rich and poor, saint and sinner alike. One of the figures at her feet is a god. In that sense, one can read into the carnage a message of universal camaraderie. Very few of us will be crucified, but all of us will suffer deprivation.

This seems to be the view people in the East have of Christianity — that it’s grim and punitive. If a Buddhist or Taoist is a bad person, they suffer consequences in the next life, but they are also given a chance to do better. If a Christian is a bad person, or even if she is a good person but simply not Christian, she suffers eternally.

Christians, of course, wouldn’t call themselves pessimists. They greet you with the words “Have you heard the good news?” But for an Easterner, it’s hard to take that news (of Jesus’ resurrection) as anything but a stay of execution for a crime they didn’t commit — gaslighting writ large.

I never really thought about it, how people in the East perceived Christianity, until I came across this passage from Osamu Dazai’s 1948 novel Ningen Shikkaku (“No Longer Human”), in which that pessimism is referenced offhand.

For context, the novel has nothing to do with Christianity or religion. This is simply an offhand remark made to the narrator, a Japanese man. It is not a remark of note. But that’s the point. By its very triviality, it reveals the unconscious image.

[image error]

The book is excellent, by the way.

January 16, 2019

(Music) Cratediggers: Rare Pop Nihon

[image error]

Kyu Sakamoto stands over popular music in Japan the way Frank Sinatra stands over popular music in the U.S. This song actually made it to the Western charts with the title “Sukiyaki,” which is a kind of food and has nothing to do with the song. The Japanese title, “Ue o Muite Arukō,” means something like “looking up as I walk.” A Newsweek columnist noted that the re-titling was like issuing “Moon River” in Japan under the title “Beef Stew.” But then that kind of casual racism was rampant in the 60s.

This song was recorded for the 1973 thriller Lady Snowblood, based on the manga of the same name, about a woman who takes revenge on the men who raped her mother and killed her family. Meiko Kaji, who sings the song, also played the lead role.

In the mid- to late-70s, Boomers in the West were chilling to instrumentals by Herb Alpert, Chuck Mangione, and Barry White. Hiroshi Suzuki created an exceptional if largely unknown entry to the genre in 1975.

Starting in the late 70s, as the Japanese economy starting taking off and her pop culture began to seep westward, a number of artists began singing in English as Hiroshi Satoh did on his 1982 EP.

Mariya Takeuchi’s 1984 hit “Plastic Love” took off on YouTube recently thanks to the synthpop revival and the platform’s obscure recommendation algorithm. One 2016 remix has amassed over 7 million views. Here is the original.

This next song is pretty obscure. The artist, however, is one-third of electronic music pioneers Yellow Magic Orchestra. (Another member is Oscar-winning composer Ryuichi Sakamoto.)

I’m not sure what to say about “Sports Men.” Check it out.

And finally here is one by YMO, mentioned above. Hasono, Sakamoto, and Takahashi formed it as a kind of parody of a parody, their music being an intentional play on the West’s stereotype of Asian popular music of the era.

January 15, 2019

Greetings from Japan

Running up through the torii gates, which mark the boundary between the sacred and the profane.

[image error]

There are two kinds of religious buildings in Japan: temples and shrines. Temples are Buddhist. Shrines are holy places, spiritual emanations, of traditional Japanese culture, which is often called Shinto — or worse, Shintoism — in the West.

In my experience, your average Japanese person wouldn’t know what to make of the question “Are you Shintoist?” — unless they had spent time in the West, with its tireless emphasis on dogma (to the point that most Christians and Muslims and Atheists don’t even consider it dogma, simply rational belief).

There is no such thing as Shintoism, just as there is no such thing as Hinduism, which was invented by British observers of India as a means of translating the native religious experience for the people back home, who require their faiths to be rational: clearly demarcated, nominally consistent, hierarchical.

India’s case is somewhat unique in that the advent of Islam forced, by conflict, some demarcation. Hindus self-identify as Hindu (whereas the Chinese, who also have a traditional religion with no name and no dogma, do not self-identify as anything but Chinese). If you spend time in India, you learn quickly there is no such thing as Hinduism, at least as we imagine it in the West. There are only Hinduisms — nearly as many as there are Hindus.

Each village in India will have its own deity, for example. That deity may be shared with other villages or it may be unique. That deity may be identified as an emanation or avatar of some wider deity, like Shiva or Vishnu, but if so, he or she is rarely worshiped that way. Villagers will have bhajans and festivals, which are shared worship, as will households, but the deity is open to all and each person will conceive of him or her in their own way.

Gurus, then, are insightful men who have conceived of some new way and who preach it to others. For this, they are not nailed to anything.

Most Japanese have an innate and unspoken reverence for nature, and beyond it, what you might call the deep roots of the universe, whose growth and movement one can never fully comprehend. Japanese society is highly structured. Her students excel at math and science. But even the most logical among them will talk casually about a certain something that it is almost impossible to render into English. We might say forces, but the word force implies moment and direction. Tides might be better. Tides of history. Tides of society. Tides of the cosmos. We are caught in these tides. They are not invisible, but neither are they easily explicable.

In the West, religious tribes gather every week and speak words in unison that both identify and distinguish them, even from other sects of the same faith. Collectively, they are like the tiles of a Roman mosaic, each neatly abutting the next with no overlap.

The sects of Japanese Buddhism — zen, for example, which is the Japanese version of the Chinese chan school — might disagree with each other about which is the best path to enlightenment, but none of them would suggest theirs is the only path.

And Buddism itself is somewhat agnostic about the divine structure of existence. Its texts speak of many gods, innumerable gods from this universe and others, who watched the Buddha attain enlightenment. In that sense, Buddhism can be adapted to almost any religion. It is not so much a faith as an exit.

What we call Shinto is the native Japanese religious experience which grew organically on the islands and which, while having certain characteristics, is not a dogmatic system. It does not have adherents, only believers.

To that is added Buddhism, which neither extends nor contradicts its partner. It merely offers another way out.

—————————————————————-

I am in Japan through the end of the month. Posts might be sporadic for the next few weeks.

January 14, 2019

Lionel Walden (American, 1861-1933) The Night Train

Lionel Walden (American, 1861-1933) The Night Train

[image error]