Rick Wayne's Blog, page 52

March 21, 2019

(Art) The Airy Celestials of Clockbirds

March 20, 2019

(Art) Cover Madness!

[image error]

The latest cover designs for my forthcoming occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. Covers are not for fans but for those unfamiliar with the book, so hopefully this is intriguing.

The book is split into two parts, which is not a function of verbosity but of the story’s unique qualities. It is actually five mysteries, five short (pulp-length) novels, each with a separate narrator, where the POV character is never the main character.

The main character appears in each story and plays a key role in the development and solution of the mystery, and in that way he functions as the detective.

I wanted to tell a mystery from the point of view of a “secondary” character, someone affected by the crime — a family member or friend of the victim — rather than from the point of view of the detective, which is how almost all mysteries are told.

That presented some interesting challenges. Secondary characters in a standard mystery are basically passive. They appear, like NPCs in a video game, at just the right time to give the detective vital clues.

This is because the standard rules of narrative storytelling dictate that, even if there are shifts in POV, there is one character (sometimes two, very occasionally three or more) who “stitches it all together” for the reader.

This is not a bad thing. Reading is supposed to be fun. In my experience, odd narrative constructions, no matter how clever, are usually more of a hindrance to the story than a benefit.

Thus, in most mysteries, the people affected by the murder basically sit around waiting for the police or profiler or P.I. to do their job.

If those folks are active in any way, one of two things will happen: they will be a hindrance to the detective, someone whose wild and undisciplined actions jeopardize the investigation; or they will join the detective as an assistant. In either case, a single narrative thread is maintained.

[image error]

Such a contrivance is “anti-real” in that it almost never happens that way in real life, where a murder investigation will be handled by many people and the person who, say, gets the confession might be a lawyer or law enforcement officer who had nothing at all to do with the initial gathering of evidence.

In breaking that single narrative thread, I was not simply trying to be tricksy.

The occult and mystery genres go well together. Like two wind instruments in the same register, which can be played at the same time, they’re both about the sinister movement of unseen powers.

It serves an occult mystery, then, if in the process of following the trials and resolution of one character’s eerie crisis, the audience gets glimpses of deeper movements still, of the battle between the main character, a shamanic sorcerer, and his unseen adversary — with dire consequences for those caught between.

As you might expect, as an independent creator, I’m a bit obsessed with what others are doing, including the big guys. Here are some of the covers I have collected.

March 19, 2019

(Feature) The Slippery Slope

[image error]

Everyone uses the slippery slope argument when it suits them and opposes it when it doesn’t.

It was used by the Left against the partial-birth abortion ban in 2003. It was used by the Right to oppose gay marriage in 2015. Both sides continue to use it today on any number of issues, from guns to immigration to the environment.

The slippery slope argument presupposes, usually without argument, a starting condition so precarious that the slightest tremor triggers a feed-forward avalanche, inevitably depositing us into the complete contrary condition from which we will be forever immovable, buried as we are under all that rubble.

In that way, the slippery slope argument is fundamentally superstitious, not to mention arbitrary and authoritarian, since by its very nature it denies problems rather than seeks solutions to them and opposes curiosity or experimentation of any kind. It is the intellectual and political equivalent of putting “Here Be Dragons” on a map. Whether there are any dragons is not open to question. You’re just not supposed to go there.

The argument, however, is not invalid — in the formal sense. A metaphorical slippery slope could exist. (I can recommend a good paper for anyone interested.) But that’s only true of its weak form. In its strong form, which is how it’s usually employed, it is no different than a false dilemma.

False dilemmas positively pervade politics, advertising, and polite speech. The reason is simple. They’re convenient. They pacify a complex and uncertain world. They take the crust off the sandwich of thought and peel its fruits and vegetables of their difficult-to-chew nutrients.

I suspect they’re also hard-wired into the brain, which we now know is a cognitive miser; it doesn’t want to think about anything it can invent a good reason not to.

Toward that aim, the slippery slope argument works better than a false dilemma for being deceptively cloaked. The slippery-slope arguer acknowledges, passingly, the existence of numerous possible alternative outcomes. Pragmatically, however, there are really only two: for or against, a tenuous present or a dystopian hell, with nothing between. A classic false dilemma.

In my experience, that is almost never the case. In my experience, the world is — except under certain rare fringe conditions — actually refractory to large-scale change, an uphill slope rather than a downhill one, where it gets harder and harder the more you push.

This is especially true in politics, where popular movements tend to weaken as early successes are achieved and the perception of risk abates, which explains why goal-directed change is rare in history — which brings up the second, latent function of slippery slope arguments: they empower a ruling elite.

If a slippery slope argument is true, not only is complexity denied and understanding irrelevant, dialogue is as well. There are only two choices, one of which we know to be right, so engaging on the other is a waste of time.

In that way, belief in the slippery slope is socially stable because it insulates the believer against alternative information. Group coherence is conserved, and the status quo–be it on the Right or Left–is reinforced, which is reassuring to in-group members.

This is why even small political battles tend to be championed on both sides as existence-level threats, with extreme labels applied to the opposition and internal dissent shouted down.

As such, I’ve found use of slippery slope arguments to be a fair proxy for small thinking.

March 18, 2019

Another giant monster from Josh Guglielmo’s “Age of the ...

[image error]

Another giant monster from Josh Guglielmo’s “Age of the Atom” project.

The most important thing we learn at school is the fact that the most important things can’t be learned at school. —Haruki Murakami

This quote gets turned into an argument against education by people who should’ve paid more attention at school.

March 17, 2019

(Art) The Airy Celestials of Clockbirds

March 16, 2019

“Ronald” by Sylvain Sarrailh, AKA Tohad.

[image error]

“Ronald” by Sylvain Sarrailh, AKA Tohad.

March 15, 2019

As someone who sculpts in words and sentences for a livi...

[image error]

As someone who sculpts in words and sentences for a living, I find this fascinating.

March 14, 2019

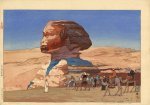

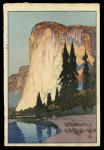

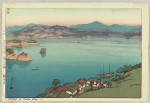

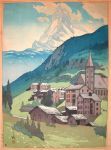

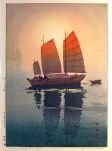

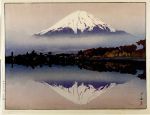

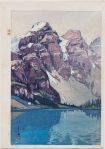

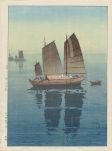

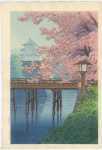

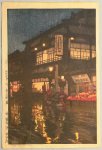

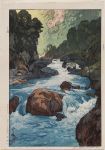

(Art) The Sublime Majesty of Hiroshi Yoshida

[image error]

Hiroshi Yoshida (吉田 博, 1876 – 1950) was a 20th-century Japanese painter and woodblock printmaker. He is regarded as one of the greatest artists of the shin-hanga style, and is noted especially for his excellent landscape prints. Yoshida travelled widely, and was particularly known for his images of non-Japanese subjects done in traditional Japanese woodblock style, including the Taj Mahal, the Swiss Alps, the Grand Canyon, and other National Parks in the United States. [Wikipedia]

March 13, 2019

(Fiction) A Town in Poland

[image error]

I went to the little boy’s funeral. But I didn’t join the crowd. I saw his young mother, standing there, hunched and broken, and I couldn’t bear to face her. It wasn’t just that I’d told her we’d fix it. That I’d told her I’d fix it. She reminded me too much of my own mother, in similar circumstances, when we buried Bug. This boy, at least, had mourners, mostly older women in blacks and deep purples who glanced at the trembling girl, unsure whether to hug her or give her space. I still wanted to talk to her, to say something, whatever I could, but I wanted to do it away from all those shifting eyes. I was a coward, I guess. I didn’t want to admit before anyone other than her that I had failed. Maybe it wasn’t cowardice. Maybe it was pride again.

A small crowd gathered as I watched from behind a towering monument to some dead businessman nobody knew. Words were spoken and more tears shed. The breeze was as still as the bodies in the ground, and I could hear the sniffles from across the lawn. About halfway through the service, a car pulled to a stop on the drive, a car I recognized. Ollie stepped out, dark overcoat over a stiff formal suit. He clutched a string of beads in his hand from which hung a cross. I watched him join the crowd and bow his head in sadness as the tiny casket was lowered into the earth. It was sleek and shiny, like the occupant was riding a toy limousine to the other side. A prayer was read, and Ollie’s thumb moved the beads one at a time. For all his gruff talk, he was as human as the rest of us.

Then it was over, and I felt a small panic. I’d taken a rideshare to the cemetery. I hadn’t planned on being a coward and needing an escape to the street. I turned about, looking for any retreat through the wide-open gravestones that wouldn’t leave me exposed, when I heard a familiar rumble, like the purr of a big cat. Behind me, past the tidy rows of the dead, the black Jaguar pulled to a stop. Milan was behind the wheel. She waited for me. She was alone.

I wove through the headstones as nonchalantly as I could and got in without a word. I didn’t look to see if I was spotted. She, at least, seemed to understand my predicament and pulled away in silence. Once again, we hit nothing but green lights and made the freeway in record time. Not that I noticed it then. My mind wandered to the little casket and the similar one my brother lay in and to my daughter and to the conversation with my wife the day before. I wondered how much extra was “extra money” and how many hours a week was “a few.”

My left hand was on my knee, which shook up and down nervously. I only noticed when I caught Milan glancing at me glancing at my wedding band. Our eyes met.

“Nervous?” she asked.

“About what? You haven’t even told me where we’re going.”

She nodded weakly, like she knew there was more behind my agitation but didn’t want to argue.

“Just say it,” I said.

“I don’t want to pry.”

“I’m a big boy. I can say no.”

“You wear a wedding ring.”

“But?”

“You don’t appear to be in possession of a wife.”

“She’s at home. In Atlanta. Watching our daughter.”

“Why didn’t they come?”

“It’s a temporary appointment.”

“Ah. And you didn’t want to take your daughter out of school.”

I shook my head. “She’s not in school yet.”

Milan turned from the road for a moment to look at my face.

“Marlene thought it would be better for her,” I explained. “Our daughter does better with a routine.”

“Don’t we all,” she added softly.

“And you?” I asked.

“What about me?”

“What’s the deal with you two? Not that I want to pry.” I used her words. “You’re not his girlfriend, obviously. You’re not his family either. You seem a little overqualified to be his personal assistant.”

“Overqualified?”

“Yeah. So . . . ?”

“It’s complicated,” she said, without sarcasm.

“So you do mind me asking.”

“Not any more than you.”

I nodded once. “Fair enough.”

“Perhaps we would both be more comfortable saving the personal affairs for another time,” she suggested.

“Will there be another time?”

She didn’t say, and I turned to the window. We were heading out toward Long Island. Rows of town homes and apartment blocks gradually gave way to drive-thru restaurants and neighborhoods with narrow yards.

“My wife and I decided to use the appointment as a trial separation,” I said finally.

“I’m sorry to hear that.” She sounded like she meant it.

I glanced to her slender, manicured fingers lightly turning the steering wheel. No rings.

She saw me looking.

“You ever married?” I asked.

She nodded. “Once.” Then she bobbled her head like she was hedging. “Basically.”

“Basically?”

“Common law,” she explained, glancing to me politely. “Not in the States.”

“Oh? Where are you from?”

“A town in Poland.”

“A town in Poland?” I asked incredulously. “That’s an unusual way to put it.”

“I’m sorry. English isn’t my first language.”

“Your English is better than mine,” I said. “Damn near flawless actually. But okay. A town in Poland.”

We were quiet for a moment.

“What makes you think there’s any significance to it?” she asked.

I motioned to her hands on the wheel. “Your nails are perfect. Your hair is perfect. Your skin is perfect. Every time I’ve seen you, your shoes have matched your blouse and your hair has matched your pants or whatever the rules are. But when I ask you where you’re from, you don’t say Poland, which is what a Polish person would say. I get ‘a town in Poland.’ And that’s it.” I turned to look at her as she drove. “But maybe I’m wrong.”

“You’re not wrong,” she said without taking her eyes from the road.

“So you’re from a town in Poland but you’re not Polish?”

“Correct.”

I waited for an explanation. When there was none, I turned back in my seat. “Okay.”

It was a few minutes, maybe longer, before I understood. “The town is in Poland now, but it didn’t used to be Poland. It used to be a different country.”

“Something like that.”

“I wasn’t aware the Polish borders had changed in our lifetime.”

She smirked. “He was right about you.”

“Oh?”

“You’re the clever man.

She emphasized the word ‘clever’ slightly—not enough to suggest it was a joke, just enough to imply there was something more. But whatever that was, she didn’t explain. All I got was “I hope it’s enough.”

“Enough for what?” I asked.

“Whatever we’re about to face.”

“You don’t know either?” I studied her face. “Why’d he ask me about my daughter?”

No reaction.

“I don’t know,” she said finally. “You’d have to ask him.”

“You don’t have a guess?”

“I’ve learnt it’s usually better not to guess.” She glanced to me from the road again. “With him, things are rarely as they appear.”

I nodded once more and added under my breath, “I’d buy that.” I spoke louder a moment later. “I have another question and I’d like a straight answer please.”

“Okay.”

“How much of yesterday was a recruitment interview?”

“What do you mean?”

“You showing up like that. It’s like what the military does with inner city kids—send a sharp-looking recruiter to the schools and playgrounds, see who’s got the moves, approach them and see how desperate they are. Then make a pitch.”

“They approach you?”

I nodded.

“But you didn’t say yes.”

“I was lucky. I had an alternative. Seems to me yesterday was all about seeing if I could keep up. Whether I would take no for an answer. That kind of thing. Am I right?”

She turned and smiled. “You’ll never know.”

“That’s your straight answer?”

She nodded out the window. “We’re here.”

I read the brick sign next to the street. John D. Bailey Palliative Care Center.

“A nursing home? Is this a joke?”

She pulled around the corner to a burger joint, rather than into the center’s parking lot, and stopped.

“You want to know who’s responsible for everything that’s happened,” she said in the quiet car. It was half statement, half question.

“Of course.”

“So do we.” She nodded toward the big block of a nursing home.

The architecture was modern of course, but it was every bit as dour as an old English mansion. It was shaped vaguely like a typewriter. The residential block at the back was only two stories tall. The entryway poked out from the wider main floor. Doors marked “Exit” and “Enter” were separated by ten feet of wall and surrounded by sidewalk and shrubbery. The whole complex was covered in tan striated brick, the kind popular for government and university buildings in the ’60s and ’70s, and there were too few windows. AC units on the ground floor were covered in metal cages, apparently to keep them from being stolen. Box-shaped sodium lamps jutted from the exterior in pairs, like watchful eyes. All in all, it was oppressive—a utilitarian fortress designed, above all else, to prevent lawsuits.

“You think our smuggler is here?”

“I didn’t say smuggler.”

“So why don’t you talk to this person?”

“You can go places we cannot, remember? She knows us. She doesn’t know you.”

“She?”

There was a short pause.

“Granny Tuesday,” she said.

“Granny?”

“He left you instructions,” she added quickly.

I felt like the child of a wayward parent, coming home to an empty house and a note that said dinner was in the oven. “And where is he again?”

“Busy.” She handed me a piece of plain white paper folded in quarters. “Preparing.”

“Preparing for what?”

I opened it. It was a five-item list composed in simple, neat handwriting.

I read the first item out loud. “Take nothing that could identify you. No wallet. No telephone. No watch or jewelry.”

Easy enough. I took out my phone and wallet and slipped them into the pocket of the car door.

I read the second item. “Let nothing pass your lips. Accept neither food nor drink.”

I looked at Milan as if to confirm the directive’s authenticity. She nodded.

I read the third item. “Don’t let her touch you, even in greeting. Keep your hands to yourself at all times. Seriously?”

I looked again.

She waited.

“Fine.” I read the fourth item. “Present her the coin, but do not let her touch it, even to verify its authenticity. Under no circumstances must you let her have it. What coin?”

She held up a tarnished gray silver dollar, or at least that’s what it looked like. I took it.

“What is it?”

I couldn’t tell the country of origin or the denomination. There was a head in profile stamped on one side, along with some words, but both had faded to mere bumps on the metal, as if whoever had owned it had been rubbing it for luck.

She nodded to the paper.

I read the fifth item. “Offer to sell it. But accept no bargain. This point I cannot stress enough.” And under that: “Make no terms with her, for you will lose more than you know—all that is dear.”

I read the list again to myself. I held up the tarnished silver.

“Where am I supposed to say I got this?”

“You aren’t. The less you tell her, the better, which means the less you know, the better.”

“I don’t know anything.”

“Exactly. She’ll know if you’re lying.”

“That seems backwards to me. But whatever.” I looked at the list again. “So, wait. If I can’t tell the truth, and I can’t lie, what the hell am I supposed to say?”

“I’m sure you’ll think of something. You’re the clever man.”

“Right.” I folded the instructions again and slipped them into my pocket. “So, I have to act natural, but I can’t shake her hand or otherwise let her touch me. I can’t accept anything she offers me. I have to tease her with the coin without actually offering it in the hopes she’ll reveal something I don’t know. Got it.” I reached for my bag in the back seat.

“Leave it,” she said.

“Right,” I repeated. I let go of the strap.

“The ring, too,” she urged.

I looked down at my wedding band.

She held out her hand. I looked at her bare palm, at her perfectly manicured nails. I slipped off the ring and put it in her palm.

“Please don’t lose it,” I said. “I’m not done with that yet.”

I got out and was halfway across the street before I heard her door open.

“Doctor,” she called.

I turned.

“Please. Be careful.”

rough cut from my forthcoming hard-boiled epic occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS.