Rick Wayne's Blog, page 55

February 9, 2019

February 7, 2019

(Music) The Inarticulable Majesty of Being

[image error]

I find it difficult to answer the question “What is your favorite movie?” but not because I don’t have one. I don’t have a favorite color, or even one favorite food, but I do have a favorite movie — except it’s not really a movie. Sort of.

The reason it’s a tricky question to answer is because this particular movie, although it is feature length, has no characters, no dialogue, and no real narrative of any kind.

I’m talking of course of Ron Fricke’s 1992 audiovisual epic Baraka, the opening of which is included above.

The film opens in the vastness of the Himalayas — the ancient earth, out of which the “human story” emerges — before cutting to Japan, where snow monkeys bathe in an open-air onsen, just as humans do, and seem to enjoy it just as much.

The camera focuses on one monkey, who is drowsy from the hot water, and just as it closes its eyes, the screen cuts to footage of an eclipse (and thence the title sequence), as if the monkey is dreaming all that follows.

There is of course no single correct interpretation of the film, but I always took that to be symbolic of mankind’s awakening, which is of course a good place to start a movie about our species.

Through the remaining 90-some minutes, the viewer is shown a series of “arcs,” for lack of a better term, that touch on almost every aspect of humanity, both good and bad.

Everything about the film is exceptional, from the composition to the cinematography to the soundtrack, which is how I first discovered it (back in the days before everything you ever wanted to find was on the internet). I owned a CD of the soundtrack for several years before I finally saw the film at a special screening in college.

Shot in wide 70mm film, it’s sort of the OG hi-def, equivalent at least to 8k ultra-high definition, to which it has since been converted. Even in an era inundated with high definition images, it’s still breathtaking.

The title track, which was remixed, along with the rest of the music, by ambient music legend Michael Stearns, is “Hon Shirabe,” a piece of classical music for the shakuhachi, or Japanese bamboo flute, one of the basic instruments of Japanese classical music (along with the shamisen, koto, and drums).

The name “Hon Shirabe” translates roughly as “basic melody,” and it encapsulates the basic skills and philosophy of shakuhachi playing. Almost any student will be required to master it at some point. Unlike most Western music, however, students of this piece are encouraged to play it as quietly as possible.

Here is Kohachiro Miyata’s album “Shakuhachi,” which opens with the same piece (without the remix), for those interested to hear more.

February 5, 2019

(Fiction) Face Like a Bat

[image error]

My house, barely more than a hovel, sat on the south side of a green pillow of a hill, between a pair of very old oaks. My neighbors were terribly suspicious at first, and rightly so. Under communism, Romania had been forced to import a number of skilled workers from Russia and East Germany, 90% of whom later left, taking much of the country’s wealth with them, so outsiders were viewed with a mix of curiosity and skepticism. I believe the rumor was that I was a former KGB assassin who had fled the collapse of the Soviet Union—and reprisal—to hide among those remote hills. After overhearing the story at a neighbor’s house, which doubled as a small market, I fostered it by leaving Soviet paraphernalia half-hidden under books, as if they were fragments of a former life. That lie, however inconvenient at the end, was for a time far better than the truth. It explained, for example, why I never revealed details of my past and why, despite my apparent youth and good looks, I chose to live alone. But mostly, its value was that it encouraged people not to ask.

That cloud of uncertainty, however, meant that to the villagers I was an inchoate mix of assassin and witch. Hence, every anomaly, from missing livestock to unusual accident or death, saw me the first to be questioned, which is how I came to know the lanky and impressive Inspector Dragoș, who I noticed one morning walking with his contingent up the path from the road at the base of the hill. His eyes were covered in dark glasses, as they nearly always were, and his stout nose jutted over his bushy black mustache. The inspector had detained me seven times, always accompanied by at least four other officers, as if he actually believed the rumors that I was a cold-blooded international assassin. I never knew whether to be flattered or insulted.

He stopped at the knee-high picket fence that surrounded my lot, despite that he was a tall man and could’ve stepped over it easily.

“Miss Dubrovna,” he said with a polite nod.

Irena Dubrovna was then my alias. I made no secret of my Russian heritage. There was no point. It was hard enough living day after day under an assumed identity. Adding an assumed nationality on top of that just seemed exhausting. I chose the name Dubrovna because it had been the family name of one of my nursemaids and so was familiar to me. I chose “Rena” because it sounded similar enough to Mila that I wouldn’t have trouble learning to respond.

“Inspector.” I stood up from my garden. My hands were filthy, and I wiped the sweat from my forehead with the back of my wrist. “How nice to see you again. What is it this time? Has someone’s horse turned up lame? Perhaps Old Man Ruchik has had another fall.”

“Please.” He motioned to the cars idling on the road below, one of which had a back door open in anticipation of my arrival. It looked like a giant beetle readying for flight.

I pulled the red bandanna from my head and wiped my hands on it. There were four men behind him. I was sure there were at least two more behind the house, blocking any escape, a fact confirmed to me a moment later when my chickens made a ruckus in their coop by the back door.

I held up my dirty hands. “Give a lady a moment to clean up?” I asked in Hungarian.

My Romanian was weak, which the inspector well knew. Most of our interviews had been conducted in Hungarian, which was reasonably common. In fact, I believe the good inspector was one-quarter Hungarian on his mother’s side.

“I’m afraid not,” he said. “You will need to come now.”

I heard heavy footsteps trampling the flowers on the sides of my house, the ones I had just planted. I sighed.

“Must be serious,” I said.

But he didn’t respond. He simply turned and raised his hand to the car as one of his lieutenants opened the squeaky gate in the fence and held it for me.

“A gentleman,” I said in simple Romanian.

A barrel of a woman with shoulders like a cage and a face like a bat stepped out of the car as I approached. I raised my arms and waited for her to frisk me. It was her only duty, and she carried it out rigorously and with military efficiency. Once everyone was sure I was unarmed, I got into the back, where Inspector Dragoș sat on one side of me and his lieutenant on the other. After a brief wait in the hot car, where I’m sure everyone could smell my sweat and the dark earth on my fingers and boots, we were joined by two more cars carrying the rear guard—seven more men, making a very unlucky total of thirteen. From my house, we drove in silence for nearly an hour until we reached the closest city. We stopped in front of a dour single-story structure with an asphalt roundabout in front. Above the door, I saw the golden eagle of the Poliția Română.

Dragoș’s lieutenant took me to an interview room while the inspector carried out official business. I was allowed a restroom break, and when I returned—fingers and nails finally clean—Dragoș was waiting for me, mustache and all. He had replaced his sunglasses with tinted eyeglasses through which he studied me with years of experience. The inspector had grown up under a dictator and survived a change of regime, which had left him as hardened as any big city beat cop. From what I gathered across our numerous encounters—mostly in brief snippets of conversation with his lieutenants, too young to know better than to talk to the suspects, especially the pretty ones—Dragoș was the son of farmers and approached law enforcement with a similar philosophy. To him, justice wasn’t something that was dealt, case by case, so much as it was sown. I was certain that if he felt I had committed a crime, even if he couldn’t prove it, he would have no difficulty charging me with a different one entirely, perhaps even a false one, as long as there was parity.

However, he was not corrupt, and the reverse was also true. If he was sure I had not committed a crime, Inspector Dragoș would not be the one to see me punished for it.

“Your papers are forged,” he told me through a haze of cigarette smoke. “We have enough to arrest you right now.”

Feels good to be writing again. Another rough cut from the fifth and final course of my forthcoming full-course occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS.

cover image by Qistina Khalidah

February 4, 2019

“The Magic Circus” by Mark Ryden

[image error]

“The Magic Circus” by Mark Ryden

February 2, 2019

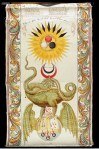

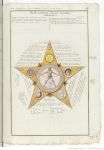

(Art) The Spiritual Art Deco of Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn

[image error]

Olga was born in London as the oldest child of Dutch parents, Truus Muysken (1855–1920), a feminist and social activist, and Albertus Kapteyn (1848–1927), an engineer and inventor and older brother of the astronomer Jacobus Kapteyn. At the end of the century the Kapteyn family moved to Zürich, Switzerland, where her mother became the center of a group of reform-minded intellectuals. There, Olga studied art history, became an avid skier and mountaineer, and in 1909 married the Croatian-Austrian flutist and conductor Iwan Hermann Fröbe, who shared deep interest in aviation and photography with her father. In 1920 Olga and her father visited the Monte Verità Sanatorium in Ascona, Switzerland, and a few years later her father bought the Casa Gabriella, an ancient farmhouse nearby. Here Olga spent the rest of her life. She began to study Indian philosophy and meditation and to take an interest in theosophy. Among her friends and influences were German poet Ludwig Derleth, psychologist Carl Jung, and Richard Wilhelm, whose translation of the I Ching made it accessible to her.

In 1928, with as yet no clear purpose in mind, she built a conference room near her home. Carl Jung suggested that she use the conference room as a “meeting place between East and West” (Begegnungsstätte zwischen Ost und West). This gave birth to the annual meeting of intellectual minds known as Eranos, which today continues to provide an opportunity for scholars of many different fields to meet and share their research and ideas on human spirituality. The name “Eranos” was suggested to her by religious historian Rudolf Otto, whose human-centered concept of religion had a deep impact on the origins and evolution of Eranos. Carl Jung also remained a significant participant in the organisation of the Eranos conferences. Although the symposia were not specifically Jungian in focus or concept, they did employ the idea of archetypes. [Wikipedia]

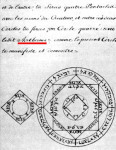

With titles like “Eternal Energy” and “The Chalice in the Heart,” it’s clear that Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn to find a kind representative archetype beyond form. Her art is precise and geometrical and her images are often reminiscent of impossible structures, like the secret form of the divine. But they are as much decorative as investigative, and many, like this first image below, clearly reveal a root in the art deco movement of the 1920s.

[image error]

For more from this tradition, see (Art) The Trances of Hilma af Klint.

January 30, 2019

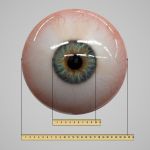

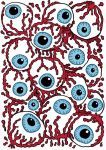

(Update) The eyes have it

[image error]

I always feel like

somebody’s watching me

Sixteen more images to update my The eyes have it collection.

January 29, 2019

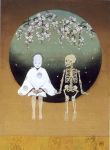

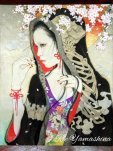

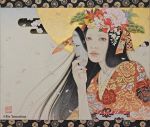

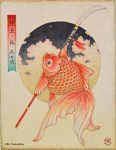

(Art) The Death-Dreams of Rie Yamashina

[image error]

The work of Rie Yamashina explores the same themes of body, identity, and death we saw in my earlier post, Macabre & Erotic Obsessions: Contemporary Japanese Illustration.

January 28, 2019

Remember, you’re basically a meat robot running open sou...

[image error]

Remember, you’re basically a meat robot running open source monkey bloatware.

art by Shih Mao

January 27, 2019

Truth be told, I could pretty much spam you all non-stop...

[image error]

Truth be told, I could pretty much spam you all non-stop with book quotes and art. Not sure what that says about me.

This is another fantastic piece by Lizzy John. Seems to me we all feel like this sometimes.

January 26, 2019

Why Read What Isn’t True?

[image error]

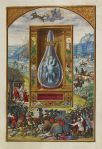

In researching this book, I have amassed quite a miscellaneum of the occult. I am continually surprised by the depth and complexity of thought.

I suppose because we have since decided that it is wrong, in that it maps poorly to the natural world, people today, even educated ones who should know better, seem naturally to adopt the chauvinistic stance and infantilize the occult, as if it were a pidgin of thought, despite that it was the object of the greatest minds of its era, including those responsible for its overthrow, like Isaac Newton, who was obsessed in his later years with alchemy and Biblical numerology.

In the book, I am not attempting a ‘rescue.’ I’m not sure there’s anything that needs rescuing. However, studying discarded images of the world is, I believe, still the best way to reveal the frailties of our own.

For example, most people in the West are familiar with the basic Aristotelian dilemma: true or not true. In the early centuries of our era, the Indian philosopher, mathematician, and mystic Nagarjuna proposed the tetralemma: that any proposition can be true, not true, neither true nor not true, both true and not true.

One expects that if physicists had been operating in that tradition, the discoveries of quantum mechanics would have come as less of a shock.

But even beside its scientific application, there is a certain wisdom in it, not least the admission that there are things that are neither true nor not true, such as my enjoyment of a movie, and that therefore arguing about them is stupid. Some men are slaves to the dilemma and can think of the world no other way.

It seems to me this is why we read, even things that aren’t true — those of us that read, anyway. Because one can memorize the encyclopedia and still be a fool.

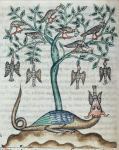

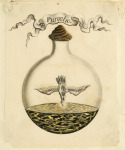

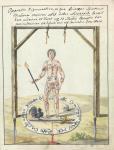

There are approximately 23 copies of the Ripley Scroll in existence. The scrolls range in size, color, and detail but are all variations on a lost 15th century original. Although they are named after George Ripley, there is no evidence that Ripley designed the scrolls himself. They are called Ripley scrolls because some of them include poetry associated with the alchemist. The scrolls’ images are symbolic references to the philosopher’s stone. [Wikipedia]

[image error]