Rick Wayne's Blog, page 58

January 3, 2019

You’re probably not really an author

I realize this is unpopular, but if you have to force yourself to write, then I’m not sure you really want to be an author.

I don’t say this to be mean, just that if you’re busy hacking yourself into authorhood (using “tips and tricks” found all over the internet), then you won’t be out discovering your true passion, which is whatever will fulfill you spontaneously.

That’s not to say there aren’t days when an author would rather be lazy. And of course I’m speaking here of would-be novelists, not marketing copyists or paid content producers. Those are occupations. They pay the rent and put food on the table.

Content production is to novel writing what house painting is to the other kind. One isn’t necessarily better than the other, but you better believe there’s a difference.

I suspect there are so many would-be authors because almost everyone possesses the basic raw materials. The state not only compels us to learn how to read and write, it also forces a rudimentary literary education in the form of English class.

The state does not compel everyone to learn how to read and write music, let alone force rudimentary music theory. If it did, literally everyone you meet would be “working on an album” (versus the mere millions who say it now).

Unlike math and music, we all make words and sentences every day, which seems like practice. We write emails and texts and stupid posts like this. We even think in language.

And we all enjoy stories. Stories are popular — TV, movies, comics, books are the most popular forms of entertainment, so writing good ones brings high social status, and who doesn’t want that?

More than that, we all daydream. (Thank heavens!) Our brains are spontaneous story-making machines that forge entire narratives out of any odd collection of facts and experience.

So if we make words and sentences every day, and we make up stories everyday, surely we can put the two together and make authors of ourselves.

Writing feels easier than other potential pastimes. Rock climbing, for example, is physically demanding. You don’t come out of high school with the raw materials necessary (unless you pursued them yourself), which means those who do it well are afforded no special status. They do it for fun.

Indeed, the sport is replete with the mantra of self-improvement. The mountain is not “defeated” for having been climbed. Rather, what’s defeated is the climber’s own weakness and limitation. It’s an act of self-improvement completed without an audience.

I’m not saying you shouldn’t write a book. People climb mountains and run marathons every year simply for the challenge, not because they want to be professional athletes. And I believe in the indie revolution, which gives everyone a voice independent of the gatekeepers.

But writing a book as an act of self-discovery, like playing golf for fun, is entirely different than doing it on the expectation that people will pay you for the pleasure of watching.

On the numbers, you are about as likely to make a living from writing books as climbing rocks. No one accepts that — or rather, we each think we’re the exception — but it’s the truth.

So it is people are busy right now setting writing goals for the year and sharing clever hacks to trick their brain into doing something it patently doesn’t want to do on its own, all on the hopes that that forced effort will nevertheless produce something people will enjoy enough to pay money for.

I try to trick myself into exercising, but then, the health benefits of exercise are virtually guaranteed. The same is true of reading. You at least learn something, if not see the world from a different perspective. So if you’re going to force yourself to do something with your state-sponsored literacy, read more books!

If, on the other hand, you find yourself perusing articles on writing hacks and motivations, if you regularly suffer “writer’s block,” if you don’t read as much as you write, I’m sorry to say being an author probably isn’t your passion. It’s a dream.

You’re free to pursue it anyway, of course. But I would suggest instead that the very best thing you can do for yourself and your long-term happiness is to spend that time discovering what your true passion is.

January 2, 2019

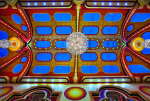

(Art) The Andean Futurism of Freddy Mamani

Since 2005, Bolivian architect Freddy Mamani Silvestre and his firm have completed sixty projects in El Alto, the world’s highest city, which sits at nearly fourteen thousand feet, on an austere plateau above La Paz. In the past twenty years, the economy there has burgeoned, along with an enterprising, mostly indigenous population. Mamani doesn’t have an office, use a computer, or draw formal blueprints. He sketches his plans on a wall or transmits them orally to his associates.

Like most of his clients, and like some 1.6 million of his fellow-citizens, Mamani is an Aymara. His people have been subject to successive waves of conquest and dispossession, first by the Inca, then by the Spanish. As a young man, he worked in construction; in his early twenties, he earned a degree in civil engineering, against the advice of his family. “It’s a career for the rich,” they told him. Architecture, too, is a career for the rich. But Mamani has made an advantage of his outsider status; he designs in an Aymara vernacular of his own invention.

Each of his buildings has a futuristic façade, a commercial ground floor with jazzy shop fronts, a baroque party hall on the mezzanine, a story or two of apartments, and an owner’s penthouse. This aerie is sometimes called a cholet, a pun on the words “chalet” and “cholo”—a dismissive racial epithet [like the N-word] that cholos like Mamani have proudly embraced. Mamani’s architecture incorporates circular motifs from Aymara weaving and ceramics and the neon colors of Aymara dress, and it alludes to the staggered planes of Andean temples. But it has also been inspired by science fiction, particularly by the Transformer movies. [text adapted from The New Yorker]

In other words, this is indigenous Andean futurism. (Kinda makes you want to treat that film franchise with a little more respect!)

What I find most heartening, more even than that the work and style are homegrown, is how much of Mamani’s oeuvre is space for the people versus the newly rich. His “cholets” have rentable banquet halls, a staple of Bolivian society since every milestone is celebrated with large gatherings of extended family. Besides being egalitarian, his architecture reflects and serves the local culture rather than recapitulating traditional modern, which is to say European, style and form, the likes of which you can find in every major industrialized city, from Dubai to Tokyo.

In addition to his banquet halls, Mamani has also worked on a number of public housing projects for the predominantly Aymara community, some of which you can see in the gallery below.

With the popularity of the Black Panther movie, Afrofuturism, which has been around for a while, is undergoing a something of a popular revival. The filmmakers were careful to design Wakanda’s capital city using African styles and motifs, including the public transportation system and the architecture of its main buildings.

Unlike that film, this Andean futurism is real.

January 1, 2019

(Music) The 35-Year-Long Explosion

[image error]

I joined Google+ in late 2012, something of an internet virgin. Prior to that, I hadn’t been active on social media to any significant degree. I immediately began sharing music, because it’s important to me, as it is for many people.

After maybe a year or so, I got frustrated at the near-total lack of engagement on my music shares. I don’t think I was purely seeking external validation. My frustration was more existential: why waste the effort if no one’s interested? So I stopped.

Which was stupid. We’re all at least as fickle as we experience everyone else to be. We like what we like and don’t what we don’t and aren’t keen to let anyone suckle our attention — just as we are owed no suckling ourselves.

I resumed sharing, and have continued since, for no other reason than that I enjoy it.

Today, the first day of a new year, I want to share a pair of tracks — or rather, a song and a short video about a song. Think of them as the entry and exit points for a uniquely American art: the fuse and its 35-year explosion.

AMERICAN RHAPSODY

“Rhapsody in Blue” (1924), which I believe marks the beginning of the so-called American Century, was built on a con.

After the success of an experimental classical-jazz concert held at Aeolian Hall, New York in 1923, famed band leader Paul Whiteman decided to attempt something more ambitious. He asked George Gershwin to contribute a concerto-like piece for an all-jazz concert he would give in the Aeolian in February 1924. Gershwin declined on the grounds that, as there would certainly be need for revisions to the score, he would not have enough time to compose the new piece.

Late on the evening of January 3, while George Gershwin and Buddy De Sylva were playing billiards, his brother Ira Gershwin was reading the January 4 edition of the New York Tribune. An article entitled “What Is American Music?” about the Whiteman concert caught his attention, in which the final paragraph claimed that “George Gershwin is at work on a jazz concerto, Irving Berlin is writing a syncopated tone poem, and Victor Herbert is working on an American suite.”

In a phone call to Whiteman next morning, Gershwin was told that Whiteman’s rival Vincent Lopez was planning to steal the idea of his experimental concert and there was no time to lose. Gershwin was finally persuaded to compose the piece.

Since there were only five weeks left, Gershwin hastily set about composing. On a train journey to Boston, the ideas of Rhapsody in Blue came to his mind. He told his first biographer Isaac Goldberg in 1931:

It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty bang, that is so often so stimulating to a composer – I frequently hear music in the very heart of the noise. … And there I suddenly heard, and even saw on paper – the complete construction of the Rhapsody, from beginning to end. No new themes came to me, but I worked on the thematic material already in my mind and tried to conceive the composition as a whole. I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston I had a definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance.

The title “Rhapsody in Blue” was suggested by Ira Gershwin after his visit to a gallery exhibition of James McNeill Whistler paintings, which bear titles such as Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket and Arrangement in Grey and Black (better known as Whistler’s Mother).

Gershwin finished his composition in a matter of weeks and passed it to Whiteman’s arranger Ferde Grofé, who orchestrated the piece, finishing it on February 4, only eight days before the afternoon premiere at Aeolian Hall. Many important and influential musicians of the time were present, including Sergei Rachmaninoff, Igor Stravinsky, and John Philip Sousa.

The purpose of the experiment, as told by Whiteman in a pre-concert lecture, was to “at least provide a stepping stone which will make it very simple for the masses to understand, and therefore, enjoy symphony and opera”. The program was long, including 26 separate musical movements, divided into 2 parts and 11 sections, bearing titles such as “True form of jazz” and “Contrast: legitimate scoring vs. jazzing”. Gershwin’s latest composition was the second to last piece (before Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1). Many of the numbers sounded similar and the ventilation system in the concert hall was broken. People in the audience were losing their patience — until the clarinet glissando that opened Rhapsody in Blue was heard.

Listen (if only to the intro).

Gershwin decided to keep his options open as to when Whiteman would bring in the orchestra and he did not write down one of the pages for solo piano, with only the words “Wait for nod” scrawled by Grofé on the band score. Gershwin improvised some of what he was playing, and he did not write out the piano part until after the performance, so it is unknown exactly how the original Rhapsody sounded.

The opening clarinet glissando came into being during rehearsal when; “… as a joke on Gershwin, Ross Gorman (Whiteman’s virtuoso clarinettist) played the opening measure with a noticeable glissando, adding what he considered a humorous touch to the passage. Reacting favourably to Gorman’s whimsy, Gershwin asked him to perform the opening measure that way at the concert and to add as much of a ‘wail’ as possible.” [Adapted from Wikipedia]

That clarinet wail is as close to a jazz call as classical music can get. Jazz wasn’t exactly new by this time. The first use of the word came some 20 years before (but no one is certain of its birth or parentage). We hear the word and think “highbrow,” but at the time, it was closer to hip-hop circa 1985 — a popular form of “street music” that made the upper classes nervous for all its associated behaviors: drinking and dancing and women with bare ankles!

I suspect Whiteman was actually aiming for the exact opposite of his stated goal. He was not trying to give the masses an introduction to classical music. He trying to give the luminaries of the age and introduction to jazz — something like a Smithsonian “urban music festival” performed at the Kennedy Center. To that aim, Gershwin, without really intending it, created the perfect marriage of jazz and classical.

In an article in Atlantic Monthly in 1955, Leonard Bernstein, who nevertheless admitted that he loved the piece, was ambivalently critical of the Rhapsody:

The Rhapsody is not a composition at all. It’s a string of separate paragraphs stuck together. The themes are terrific, inspired, God-given. I don’t think there has been such an inspired melodist on this earth since Tchaikovsky. But if you want to speak of a composer, that’s another matter. Your Rhapsody in Blue is not a real composition in the sense that whatever happens in it must seem inevitable. You can cut parts of it without affecting the whole. You can remove any of these stuck-together sections and the piece still goes on as bravely as before. It can be a five-minute piece or a twelve-minute piece. And in fact, all these things are being done to it every day. And it’s still the Rhapsody in Blue.

Born of a jazz mother and classical father, named after an American painter, “Rhapsody in Blue” is a musical assembly piece, every bit as interchangeable as the interchangeable parts upon which American industrial and military might was built. One expects that if Gershwin and Whiteman were not under pressure of competition — that most American of conditions — if they hadn’t “rushed to market,” the final piece would’ve been seamless, hefty, and polished flat.

GIANT STEPS

After 35 years of unbridled popularity, “Giant Steps” (1959) is where jazz left the mainstream. Depending on your tastes, the song either has one foot in or one foot out the door. In either case, after “Giant Steps,” jazz departs the popular consciousness, never to return.

Artists before Coltrane explored experimental improvisational techniques, of course, but those attempts were just that: tentative, abortive, exploratory. Coltrane wasn’t scouting the periphery to impress his pals. He intended to leave and never return. In the 1960s, he began playing avante-garde jazz, followed later by his own brand of spiritualist music based on Hindu and Buddhist teachings, both of which perplexed audiences and critics alike.

But “Giant Steps” is a masterpiece, every bit the giant step it claims to be. Luckily, the good folks at Vox created a wonderful short video that explains why.

And as we depart, here is the full track. Jazz didn’t “die” with this song. Jazz is very much alive today. But this was where it stopped growing, if you will. After “Giant Steps,” jazz has its midlife crisis. It tries hard to recapture its youth (check out Miles Davis’s strange concerts in the 1970s), fails, and settles into a comfortable and respectable old age.

cover image: “Adjustment Bureau” by Franz Falckenhaus

December 31, 2018

December 30, 2018

(Art) Female Representation & Sargent’s The Misses Vickers

This is The Misses Vickers (1884) by English painter John Singer Sargent.

I’ve said before that no artist mastered the female portrait quite like Sargent. Others have produced different, equally sublime works, but I’m not aware of anyone who’s surpassed him in oeuvre.

In our time, Tom Bagshaw gives Sargent a run for his money, but Bagshaw’s women, while potent and unafraid, have a certain persistent antagonism that, however much suited to the times, lacks much of Sargent’s subtlety and sophistication.

[image error]

Sargent apparently did not like the Misses Vickers, describing them at one point as “three ugly women” who “lived in a dingy hole,” not that you could tell from his portrait, which is precisely a study in such contrasts. The young ladies are wealthy, being the daughters of Colonel Thomas Vickers, a prominent industrialist, and are depicted in full and opulent dress, but their poses are relaxed and casual.

Most commissioned portraits of the time, especially of wealthy patrons, depicted their subjects vertically, standing before a mantle or vista, such that the audience must look up to them. Men were martial and commanding; women objects of beauty, if they had any, otherwise of grace and refinement.

Sargent has us looking down on the Misses Vickers, but not in disdain. It’s as if we’ve been invited to their home and caught them at a moment of relaxation. It’s true that they are, in a sense, objects of beauty in that Sargent has made them pleasing to look at, but that is not all they are. They are people in full, as evidenced by their patent and distinct characters, and they have minds — they are reading a book, for example, and relaxing with each other as real sisters do, versus the archetype of respectable nobility captured in a typical portrait.

At the other end, of course, was the nude — an entire genre, like landscape painting, devoted to naked women, the portrait of a sexual object, commissioned in cash and hung as a possession.

Sargent wasn’t alone in depicting scenes of casual home life. Far from it. The painting below, for example, by James Tissot, Hide and Seek:

“…depicts a modern, opulently cluttered Victorian room, Tissot’s studio. After Kathleen Newton entered his home in about 1876, Tissot focused almost exclusively on intimate, anecdotal descriptions of the activities of the secluded suburban household, depicting an idyllic world tinged by a melancholy awareness of the illness that would lead to her death in 1882. The artist’s companion reads in a corner as her nieces and daughter amuse themselves” [National Gallery of Art].

[image error]

The Misses Vickers, however, is notable for its composition and presentation of its adult subjects. For one, Tissot’s piece wasn’t a commissioned portrait but a work of personal inspiration, like a photograph. It is a scene of life, akin to a landscape, rather than a human study.

Compare Sargent’s painting to this one, John Everett Millais’s Hearts are Trumps, which also depicts three wealthy young women in full satin dress — here playing cards, seemingly to pass the time while they wait for husbands, or so the title implies to me. They are more or less indistinguishable from one another, and each looks either frustrated or bored: with the game, with the painting, with each other, even with the opulence that surrounds them.

[image error]

Just by looking, we know so much more about the Vickers women, below, than these three. I don’t know their names or ages, but it seems to me the eldest Miss Vickers is in front. She is dressed the most conservatively and wears the least amount of makeup. Her eyes are down as if in serious study — or else propriety — as she patiently suffers the intrusions of the youngest, next to her, who has reached out to take control of the afternoon’s entertainment.

Continuing the theme of contrasts, the eldest sister’s dress is black, the youngest’s an airy and revealing white. One is serious, the other hardly paying attention, her eyes out the window. And yet, they are clearly fond of each other.

[image error]

The middle girl is at the back, keeping to herself, as middle children do. (I am a middle child.) She is neither the most responsible nor the center of attention, yet she finds provocative ways of expressing herself. She is the troublemaker, dressed in passionate red, and she alone greets the viewer with her eyes, bringing us further into the scene, making us part of it in fact. And her hands make an interesting gesture.

The Misses Vickers is evocative for how it crams so much humanity into a single still image — and at a time women were typically seen as little more than large children, or sexual objects.

But then, as I said, Sargent had a genuine talent for female portraiture. His most daring work, Portrait of Madame X, which was completed earlier the same year, resulted in the scandal that saw him leave the high society of Paris to do commercial work at the Vickers’ country manor.

[image error]

Madame X was not a commission but a personal work by the artist. The subject, an American expatriate who married a prominent French banker, is depicted so boldly and in such a blatantly sexual manner that the work was very poorly received at the Paris Salon of 1884.

This no doubt contributed to Sargent’s expressed disdain for the Misses Vickers, who were for him a sign of how far he had fallen from the height of the art world. Of course he wouldn’t know it at the time, but as much as Madame X damaged his career in the short term, it later helped established him as a notable talent in England and then America.

Portrait of Madame X is certainly the more famous work, and it is definitely the more provocative, but I prefer the humble simplicity of The Misses Vickers, which is Sargent at his most relaxed. There is an air of in-your-faceness in Madame X that — to me, at least — makes it seem like the artist was trying too hard: to be noticed, to push bounds, and that creates distance between work and viewer. Madame X’s ironic self-display seems almost to shame us for admiring her.

Forced into country exile, painting for commerce rather than art, but also freed from the latter’s demands, Sargent produced a much more human study — three women who are not objects, not icons, not ironic, not on display, just people: sisters enjoying their afternoon together.

December 29, 2018

(Art) The Frenetic Fantasies of Jakub Rebelka

The artist uses an inspired patchwork of bright and distinct colors to blend his frenetic, meandering lines into a seamless whole. The result, while resembling a kind of impossible stained glass window or deranged paint-by-number, is nevertheless subtle, raw, and distinctive.

December 28, 2018

RISING (2007) by Michael Whelan

[image error]

RISING (2007) by Michael Whelan

December 27, 2018

(Fiction) The House

The house hadn’t always been a house. It had been a house first, but then it was a train station. It was probably more things between. After being a train station, it was abandoned. After it was abandoned, it was lost. After it was lost, it found itself a house again, a kind of refuge or dormitory in the heart of the city. I liked to think it felt good about that. It was almost always full. No sooner did a room become available than someone appeared to claim it. No one seemed to own the place, or if they did, they never bothered to show. Housework was distributed equitably by room, each of which had a color. The Scarlet Room was brown. The Azure Room was gold. I was in the Viridian Room, which was responsible for cleaning the fireplaces, among other things. That distribution, along with the rules of the house, had been painted in large letters on the wall of the Great Room, as it was known. More than one rule had been subsequently painted over and replaced (who knew how many times), including the rule that allowed for modification of the rules, which presently required a two-thirds majority but which I suspect had once been by unanimous vote only.

The house was constrained to its narrow lot, taller and longer than it was wide, which told me that that lot had once abutted others, but if so, they were long gone, replaced by buildings which all seemed to face the other way. No one looked down on the house, nor was it visible from any street. A spiked wrought iron fence, complete with swinging gate, guarded its boundary while two pairs of train tracks ran along the veranda at the rear. The human occupants of the house, who were always in the minority but acted like they were in charge, only took note of the tracks once, when they moved in, after which the tracks disappeared from everyday thought the same way hustling city-goers around the world cease to notice the vestigial remnants of long-vanished streetcars poking from the concrete under their feet — just another layer in a city that seemed to grow by them, like the sideways rings of a tree.

Beyond the tracks, at the back of the lot, was a grove of trees we called the Wilds. A fringe of weeds and shrubs grew in front of it and entombed the occasional trash that blew in from the outside — a kind of filter that kept the interior of the grove as pristine as an ancient forest. The view from the back of the house was cramped. The buildings rose up on all sides and made the little lawn seem like a courtyard, a place you stepped through on your way to other places, and we never spent much time there. But the Wilds seemed to go on forever, if you were standing inside it: a dark forest whose outer limits were obscured by an overlapping pastework of trunks and branches that seemed to peel away as you moved through them. It was widely believed other things moved through them as well, which is why we rarely entered, even to answer the phone. Inexplicably, a doorless phone booth stood just inside the margin of the trees, carpeted in dirt and leaves and sheltered by the branches, all its glass have long since disappeared. But the light at the top still worked. In fact, it was never extinguished, although it occasionally flickered when the phone rang. I could see it at night from the window of the Viridian Room. Every spring, at least one pair of nesting birds would try to make a home in the nook under the payphone, where the Yellow Pages would’ve gone, only to be scared away a few days later by the ringing, which sometimes went on for the better part of an hour. They would leave behind a husk of a nest that was eternally resumed but never finished.

I answered the phone once, shortly after I moved in, only to hear the insistent buzz of a dial tone urging me to get on with my business or else return the phone to its slumber. That was the first of only two times I entered the Wilds, which neither the sounds of traffic nor a cell signal seemed able to penetrate.

a rough cut from Bright Black, the fifth and final course of my forthcoming occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS

December 26, 2018

(Fiction) Minnow Ramsey speaks to God

Minn Ramsey spoke to God every day of her life. But it was only after blessed Preacher Martin came to town that God spoke back. And not just to her. To nearly every resident of Mountain Hide, usually on a Tuesday. It was a miracle, to be sure, given on account of their faith. It had to be. Because there was nothing else.

The town was nestled in a crook in the mountains of West Virginia, and while it started as little more than a backwoods dugout for moonshiners, it blossomed after the coal mine opened. But luck wasn’t on the community’s side, and some time after Prohibition ended the coal ran out and there wasn’t much of a reason for anyone to stay all the way up there, miles from anywhere, with hardly a decent road to the place. Decades passed and folks moved on until there were only enough tithing families to support a single church and only enough deposits for a single savings and loan. By then, everybody knew everybody else by their first names, and it seemed like a sin to leave, even though most wanted to.

But all that changed after Preacher Martin came. He didn’t seem like much at first—bald up top, a little soft in the middle, with a round nose and a pair of eyebrows that didn’t line up straight. And sometimes his voice seemed a bit off, like a record player running a tad slow. But otherwise he was the same as anyone. There wasn’t even a hint as to the miracle he carried in his heart.

Minn knew that’s how Preacher Martin was. Humble.

First thing he did was meet with each and every one of his parishioners—in private so it was more comfortable. He sat them down in his office in front of a big camera, almost like a projector, and when it snapped a picture of you there was a sound like a shutter run backward, and you could see stars in the lens. Preacher Martin took everyone’s picture that way, even the folks who weren’t regular church goers, and he wrote down everyone’s names so he could memorize them all later. He talked to folks about prayer and the Bible, about the town, about their job, their likes and dislikes, even their hopes and dreams. He was such a nice man.

But not long after he arrived, everybody got to see that Preacher Martin was more than just humble. He was blessed of God. And not like those false tent-pole healers that ran through Deerlick every spring.

When Brandon Federline, 26, was carrying on with a high school girl, just 15, God knew it, and He told Preacher Martin, who asked Brandon to come up before the whole congregation—practically the whole town—and confess his sin publicly so he could be forgiven.

Of course, Brandon wouldn’t admit it at first, not something shameful like that, criminal even. But as soon as he figured the truth—that God really was watching and that He had told Preacher Martin things only Brandon and the young lady could know—well, Brandon felt the presence of the Holy Spirit. He broke down right there and dropped to his knees. He brought Jesus into his heart and begged for forgiveness.

There were lots of tears and hugs and more praising God that day than any Minn could remember. And it wasn’t about Brandon. Minn knew lots of folks were still angry about that. It was the bigger truth. Preacher Martin was blessed. He hadn’t been in town two months and already he’d battled a secret sin in their very midst. Real sin. Born of the Devil. And he won.

And that was just the beginning. Every time someone found themselves dancing, or giving in to the temptations of the flesh, Preacher Martin would stop by, or ask them to come up to the front of the church, and he’d stroke his comb-over gently and everyone could see he had God in him. He cured people of the weed and got divorced couples to reconcile. And every Tuesday he rode through the town and delivered a personal message from God.

He even got Minn the job at Gelid Cold Storage. She only applied because God had told her to, but she didn’t like it there. She liked it better down at the bank. But God put Jaslynn Summers there, and not long after, the little bank got a big new client and millions of dollars moving through all the time, or something like that, and suddenly there was money around town. Roads that had been rotting Minn’s whole life got fixed, including the winding snake that led down the mountain. The town hall—still the original from 1924—got a new whitewash. Gelid Refrigeration Services, Inc. bought the vacant coal mine and moved in. And for the first time in a long time, things started looking up for the people of Mountain Hide.

That’s how Minn knew it was all for the best, even her job. God knew what was best for everyone. It was her place to follow His plan, even when it didn’t hardly make no sense.

Like with the deliveries. They were always at night, which seemed odd. It’s hard to see in the mountains at night. But then Minn figured it probably didn’t make a difference since everything was automated anyway. Gelid was a fancy outfit, and they had built the cold storage unit right into the mine. The company had installed brackets all along the walls of the long central shaft that ran to the lower level, all of it long since flooded with ice-cold water. It was a constant -2.3 degrees Celsius all year round, or so the computers told her, but the dissolved minerals kept the water from freezing solid. It was a natural, all-weather, fault-free freezer.

When a delivery came—which was rare—it always came off the back of a truck, and it was always the same kind of oblong metal container, like something NASA would make. The delivery guys would open the big steel door to the mine and leave the container on the yellow-and-black painted concrete pad with the blue-striped girders arching overhead, keeping the mountain at bay. The men didn’t hardly pay any attention to Minn. She guessed they were told not to.

Every now and then she’d wave, or she’d catch a glimpse of the red robotic crane in the ceiling, moored to the rock as it swung down like the hand of God and lifted the oblong container and mounted it on the appropriate numbered bracket deep in the dark water. The robot didn’t need to see, so there were no lights down there. It was silent and spooky, like one of those sensory deprivation chambers Minn had seen on Discovery TV, with nothing but the occasional drip of condensation.

And when it came time for a pick-up, the crane would get orders through the Internet. It would find the right numbered bracket, remove the container, and deposit it on the pad, cold and dripping. Later that night, the delivery company would come—it was always the same one—and a plain white semi would back into the lot. Men would hop out and remove the container and haul it away. Minn never knew where they were going or what was inside. She’d even signed some papers that said she wasn’t allowed to talk about it with anyone, which was silly. There was nothing to tell.

Minn’s job, if you could call it that, was to hang around and answer the phone that never rang and make sure there were no problems, and occasionally reboot the computers that monitored and controlled everything. Preacher Martin said it was to give Minn time to study so she could get her GED like she’d told him she’d wanted, but Minn never felt like studying, and she’d only told Preacher Martin that—in his office, that day he took her picture—because it seemed like the thing someone without a high school degree was supposed to say when asked about their “long term goals.”

In truth, Minn didn’t do much of anything, and some days she felt like she was only there for show, to make it look like there was more going on at Gelid than there really was.

But that was silly, she chided herself. God had told her to apply for the job, and He was looking out for her, she knew. He told Preacher Martin things about her no one could know. Things she did in private. Things no one else ever saw. Preacher Martin said it was okay as long as she wasn’t married, but Minn knew there wasn’t much chance of that. Not in Mountain Hide.

Sometimes she thought about leaving. She asked Preacher Martin if she could maybe get a different job, one where she made enough to save for a move, but God said it wasn’t time yet. He needed her where she was, and even though maybe it didn’t seem important, He had a plan. And it was extra super important—Preacher Martin always reminded her in that funny voice of his—that she never, ever go down into the mine. He even made her swear to it on his Bible, the big heavy one that zippered up around the sides and never left his hands. And that was fine with her. She didn’t like it down there anyway.

At the end of every shift, Minn walked across the lot from the temporary trailer that housed her office and strung the silver chain with the padlock around the links of the fence, lost in thought.

Minn felt something cold and hard being pressed to the back of her head. Was that a gun?

She heard a click.

It was. Minn froze. “I don’t have any money.” That was certainly true.

“Step back.”

Minn did as she was told. A gaunt man in jeans and leather pushed her aside and pulled out the chain. It dropped on the asphalt. He had a shaved head. There was a tattoo on the side.

Minn didn’t need to see his face, or the tattoo. She’d recognized his voice right away. So she kept her eyes down. It was Jerrad. Shawna’s boyfriend. And right then Minn knew she’d done something completely horrible. Her face twisted like she might cry.

“I’m sorry,” she breathed softly. Only it wasn’t meant for Shawna’s boyfriend. It was meant for God.

More men appeared as the sun set behind the mountain. One of them, a plump, bald man with a white head like the moon, grabbed Minn’s arm and pulled her into the gravel lot behind Jerrad. The fancy stitched name on his leather jacket said Colt. She was pulled past the trailer and shoved toward to the console, sort of like an ATM, built into the wall next to the large steel door that sealed the mine. It was painted the same color gray as the mountain rocks that surrounded it.

“Open it.”

Minn knew she was in trouble. She didn’t raise her eyes from the pebble-strewn asphalt. She pressed her arms to her side and hunched her shoulders. She wasn’t very big to begin with, barely 5’2”, but she wanted to shrink even smaller and slink away. Like a weasel.

Shawna’s boyfriend put the revolver to her head and Minn shook.

“I said open it.”

Jerrad Harbingen wasn’t from Mountain Hide. He was from Deerlick, down along the river, and he was a bad man. He ran with a motorcycle gang. Minn could only assume the other fellas were them. There were at least two more men behind her, judging from the sound of gravel crunching under boots. They all had guns. They were antsy. She could tell they were in a hurry. They looked around nervously. They were robbing the place. And Minn knew why.

God had told her not to talk about her job, not even to other folks in town. She’d signed papers and even swore on Preacher Martin’s heavy Bible. But she couldn’t help it. Her high school friend Shawna Bilken was making twice Minn’s salary working at a little boutique down in Deerlick. Minn had to listen to her brag all weekend about her job and her new boyfriend, Jerrad. He wasn’t much of a catch, what with being convicted of assault and all, but still, he was kinda cute—skinny with a bunch of tattoos, like a rock star. It wasn’t fair. And it wasn’t fair Minn had to be all alone up in the mine while Jaslynn Summers smiled and chatted with everyone and got to look pretty and wear lipstick down at the bank.

So maybe Minn talked up her job a little bit. Maybe she made it seem like a bigger deal than it was. The big robotic crane. The night deliveries. The secrecy. The oblong containers with the funny symbol on the side.

Like she was a spy.

But Minn had spoken out of vanity, and now bad things were happening.

Jerrad pushed the gun harder. “Open it!”

from Episode Four of THE MINUS FACTION, a serial novel about superhuman abilities and how not to use them.

[image error]

December 23, 2018

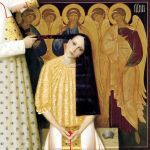

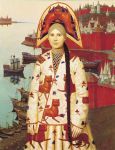

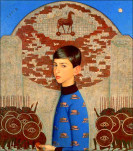

(Art) The Contemporary Iconography of Andrey Remnev

[image error]

Contemporary Russian painter Andrey Remnev graduated from the Moscow Art School in 1983 and went on to study the medieval and Renaissance iconography of the Orthodox Church. His works blend classical Russian culture with scenes from peasant and contemporary life reflecting a variety of themes, including music, beauty, politics, religion, and the persistence of history.

You can find the artist on his website.

“My own style evolved from the ancient icon painting, Russian art of the 18th century, the compositional innovations of the World of Art group and Russian Constructivism. As painters of the past, I use natural pigments bound with egg yolk.”