Rick Wayne's Blog, page 30

January 1, 2020

(Art) The Sinister Beauty of Akiya Kageichi

[image error]

Japanese illustrator Akiya Kageichi continues the themes of sex, death, and identity as explained in Macabre and Erotic Obsessions: Contemporary Japanese Illustration. His tormented lovers, sinister jesters, and disinterested kings rule fractious fantasy underworlds that are opulent with detail.

December 31, 2019

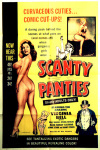

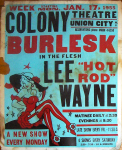

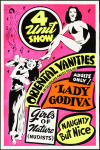

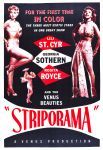

Burlesque!

December 29, 2019

(Art) The Immaculate Fables of Ddaddy Star

[image error]

Ddaddy Star, a Malay artist who also goes under the name Olafoolart, makes wonderful illustrations of characters from myth, both Eastern and Western, both ancient and modern: Asian gods, Aesop fables, Princess Mononoke, astrological signs, God of War, Pokemon, Game of Thrones, children’s books, and more: https://www.artstation.com/ddaddystar

December 26, 2019

December 25, 2019

Season’s Greetings, from one merry dumpster fire to another.

[image error]

art by Rory Kurtz

For a period in the 1950s, Galaxy Science Fiction Magazine ran a Christmas-themed cover every December. Have a happy holiday.

December 24, 2019

(Fiction) Library of Thieves

[image error]

After Beltran’s visit, some of my restrictions were lifted. I was not allowed to speak to Etude and had no idea where in the cavernous dungeons he was being held—the same dungeons where the Eye was discovered by the first maestri some seven centuries before. I was also kept from the high towers, where everything important seemed to happen. But there was a garden promenade left open to the sky and I was allowed access to it and to the library. Both were utterly, unspeakably magnificent. The library was large enough that one could genuinely get lost. I was never a scholar like Hank, but being raised in the centuries before television, books have remained my first love, and over the next several weeks, I spent many hours between those stacks in the company of voices past—not only the authors of old and cherished books but also the ghosts that would sometimes steal them when my back was turned. I learned quickly to feign disinterest before making a selection, lest the book I had chosen be whisked away behind me. Their thefts were an attempt, I’m sure, to get me to go innocently searching, to explore the buttressed vaults, caged nooks, and octagonal chambers that connected each to the other inside the same great chamber. One could lean out of portal windows or over carved-wood balustrades and see the robed librarians patiently about their work. But like truth itself, there was no vantage in the library from which all of it was visible. Chambers faced away from each other or else were blocked by stone stairways that ended abruptly in space. I was sure that through at least one of those arches—which were especially numerous at the lower levels, full as they were of columns holding the whole of it aloft—I could fall into the shadow realm.

Of all the spirits that pestered me like children in those weeks, I made acquaintance with only one. Judging from her dress, which I only caught in glimpses between the shadows, my girl was a servant in the time of Cromwell. She must have spent much of her life scrubbing the floor, for that is what she did compulsively. When she spoke, it was always to herself or to someone else not present—in King James’s English. I heard only fragments of stories, and she would often disappear midway through. Sometimes she would glance at me first, like a wild animal, as if just realizing I was there before blinking away in fright. But as one week turned to two, and two to three, my continued presence in the library coaxed a certain calm from her, as with a tiger, and she told me stories. She didn’t relate them directly, but if I sat and read near the lower arches—which were close enough to the sea that I could hear the gentle lapping of the Mediterranean—she would often appear after a gap of quiet, scrubbing the floor (always scrubbing, scrubbing) and talking to herself, which was of course talking to me. I would put a finger in my book and close it and look away from her, to the floor, and listen as she told a friend named Charlotte, who was not present, all the reasons she should stay away from the farm boy down the lane, for he was a ne’er-do-well if ever there was one. The dead are disembodied and irrational. Their world is memory, and they speak in dreams. I listened to numerous arguments with a man—a father, perhaps, or a lord—about why she hadn’t cleaned the kitchen or brushed the horses. She told a great many lies, especially about where she went when she wasn’t needed and why it was she lingered so long there.

How she came to the Keep of Solomon, I can only guess, but the reason for her departure from her home seemed clear. Her unconsummated dalliance with the farm boy down the lane had turned sour after she caught him mounting her friend Charlotte behind a tree. Realizing he had no intention of honoring his promises, for which she had cheated her lord out of a small dowry, an offense for which she could’ve been hanged, she planned to visit a “lady of the dells”—a witch—to procure her revenge. It was not to be fatal. It would merely teach the boy a lesson. But it required a day’s travel, round trip, and servants in those days did not have week-ends. She managed a clever deception involving a prized mare and the “accidental” throwing of a shoe. She was to take the animal to town, and since travel then was risky and roads sparse, schedules were always imprecise. It would’ve been easy for her to take the necessary detour, especially since she would not actually have to lead the animal on foot, as her master thought, but would be able to ride it bareback. The money she had swindled for a dowry would go to the witch as payment for services.

On the eve of her departure, the maid Charlotte either guessed the truth from her friend’s oblique boasts or perhaps stumbled upon her preparations and subsequently informed their master. Although my young acquaintance didn’t say, I suspect she was indentured—slavery in all but name—and eventually came in service to The Masters, where she met her end within the walls of the Keep of Solomon and remained there as a wayward spirit. Whatever had happened at the end, she didn’t speak of it, as if it didn’t matter to her or had only been the natural consequence of her love for the farm boy. I think she was also worried for me. I think she understood I was a prisoner of some kind, as she had been. I think she was also jealous, as the dead often are of the living, and angry at what had happened to her, and sad about it as well, and all of those emotions played out in her speech, sometimes across a span of mere sentences as she scrubbed, scrubbed, scrubbed the floor, as if wiping it of her sins.

Early one morning, while busy with a pale and brush, my friend airily explained to Charlotte that she was so beautiful and could do so much better than a simple farm boy down the lane. Amid the rest, I heard the word “escape.” It was spoken in the same voice, but the tone and cadence were different, as if interjected from a different time and place. I looked up and the young woman was peering at me. She was speaking gaily to her absent friend, but her eyes were on me.

I nodded, and she disappeared again.

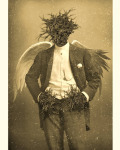

Amid the shelves of that library, I rediscovered bits of my past, including a rare manuscript by Wilm Castleby, penned in his hand. Seeing his familiar scratch brought back memories I had completely forgotten—not ones eaten by the forest but those simply lost in the years. I also discovered a collection of antique photographic plates made of glass, some of which had cracked and been mended with tape or glue. They filled a series of chests inlaid with wood grooves, each holding a single vertical plate. The Masters, or rather the librarians and scribes who worked for them in the 19th century, had used the new medium of photography to record the last of the woodfolk and the child-races, whose numbers had by then precipitously declined. Many of them had fled to other realms after the pogroms of the 17th century, but many more still had been “harvested” a century later, during the so-called Age of Enlightenment, when innumerable pieces were cut from their bodies, living or dead, and sold to fill wunderkammer and gentleman’s cabinets of curiosity. By the 19th century, precious few were left, and The Masters’ scribes made portraits, etched into glass with salts of silver. I saw twig-fingered treeherders mourning ricks of corpses, giggling gnomes hidden under furniture and machinery, preens of pixies pushed under rulers and tape measures, naked and ashamed. Some of the images were quite poignant, such as the satyr mother bent over the still body of her faun, her breasts still heavy with milk. Others were disturbing. Many of the pixies were clearly cowed by rough-gloved fingers, and their tiger-striped wings forcibly and painfully spread open. The presence of several empty slots in the chest immediately after suggested there were more such images somewhere, perhaps pornographic ones.

rough cut from the fifth and final course of my full-course occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. Part One is available now. The epic urban fantasy concludes next year with Part Two.

cover image by Andreas Rocha

December 22, 2019

My best friend lives in Japan. He introduced me to my wif...

My best friend lives in Japan. He introduced me to my wife, actually; he was trying to hook up with her friend. Across the sweep of my life, I’ve known him longer than I’ve not known him, which is still an odd thought to contemplate.

We’re both in our 40s, which is a magical time when things start going wrong with your body for no apparent reason. I remember thinking when I was younger that people in their 40s should just be in their 40s and stop complaining about it. Then you turn 40 and you’re like, wait… didn’t I just turn 30? And why does everything give me heartburn all of a sudden?

Anyway, he had to go for a colonoscopy recently. Thankfully, nothing appears out of place, but the Japanese doctor who examined him was very surprised. She told him that he had a nice long intestine, like the Japanese do, versus the shorter ones that foreigners usually have. And I thought, “You have a nice, long colon” is a compliment you would only get in Japan.

[image error]Woodblock Print by Hokusai

December 20, 2019

December 19, 2019

(Art) The Metafables of Andrew Blucha

[image error]

UK collage artist Andrew Blucha creates darkly surrealist illustrations under the moniker Metafables, which is an excellent description of his work. For more on why that’s so, see Visions of Excess.

December 16, 2019

(Fiction) Abuelita’s One Good Thing

There was nothing left of the watchtower but a cluster of broken stone walls hanging onto each other like refugees in the water. As I got closer, I could see the central chamber on the far side, or what was left of it. The nearest wall was topped in a broken, three-quarter stone circle which was empty but which I guessed had once held stained glass of some magnificence. I walked across mounds of sand, which gave way underneath me. The water came in and my feet were doused. I smelled salt and seaweed as the sound of the swirling wave echoed off the block-stone walls around me. A mural had been carved into it in the opulent Mayan style, full of open mouths and crouching figures in elaborate headdresses. It was very different than the murals in the New York and London, which were the only other “towers” I had seen. (They were towers only figuratively.) But the story it told was the same. Once the earth was covered in darkness. Then came a great battle, whence our planet was rocked and turned on its axis. And there it remains, waiting for us to pull ourselves up. Or to fall back down.

I heard a sound behind me and saw the young woman, our savior, on the beach.

“Do you know what this is?” I called, excited to be standing inside a piece of history. The Mexico City tower was the last to be used, back when the Spanish were in possession of the dagger.

She shook her head. She was clearly afraid of it and wouldn’t come near.

I looked up at it again. Then I started back. The tide was on its twice-daily pilgrimage to the shore. Soon the tower would be flooded.

“She want to see you,” the woman said. “She is very sick. Maybe now is better.”

“Who?”

“My grandmother.” She pointed up the bluff, but we couldn’t see the lighthouse from where we stood. “She is very old. Very sick. She wants to see you.”

“Of course.”

I was led back up the cliff, which took considerably more effort to ascend. I was winded when we reached the top and needed to catch my breath. But the view was spectacular. It was just then evening on the shores of the Pacific. The sun had yet to set.

“You said earlier that it wasn’t luck,” I panted. “What did you mean?”

“Abuelita said to keep the gun there. By the door. For when the demon came.”

“Abuelita?”

“It means grandmother. Really she is my grandmother’s sister. But everyone calls her Abuelita.”

We hiked back up the slope to the lighthouse, which seemed further away on return than it had at my departure. My companions were waiting for me outside of a dark room—a bedroom, it seemed, whose aquamarine walls were chipped and faded. An old woman wrapped tightly in knitted blankets sagged into a wrought-iron bed older than her. She beckoned us forward with an open hand. She was apparently unable to lift her head from the pillow. She had stout but withered shoulders, a large nose, and a square jaw, like a man’s, from which faint white hairs grew.

“My grandmother,” the young woman said. “Clara Maria Hipólita Yáñez.”

“Nice to meet you.” The doctor bowed slightly.

The room was cramped. There was barely room for all of us to stand, and we shuffled to avoid pressing against one another. Next to the door was a chest of drawers. Behind me was a curio cabinet. A tiny black-and-white television with V-shaped aerial stood on a stool at the end of the bed. Framed photos were propped on every flat surface. A lifetime’s worth. There were even some on the blanket, as if they’d been recently admired. They were all of women. The few boys I saw seemed to be their children.

The old woman tried to speak, but she was too weak, so she just muttered a few words in Spanish and smiled at us as serenely as the saints on the shelf-altar above her, where three candles in painted glass burned. The three of us stood there in awkward silence. We shared no language, but there were smiles and gestures. The old woman brought shaking fingers to her mouth, as if to indicate food, and we declined. Then she pushed out a word.

“Rosalía.”

That seemed to be the young woman’s name. She pushed forward as politely as she could in the cramped space and stuck her ear right over her grand-aunt’s mouth. Whispers were exchanged at the end of which we were politely directed to the door, which Rosalía shut carefully behind her.

“She is very sick,” she said. “But she wants you to eat.”

No one was hungry.

“That would be lovely,” I said. “Thank you.”

People had come. A trio of old trucks were parked crooked on the dirt a good hundred meters from the lighthouse. They had carted some two dozen people from the village, many of which were still crammed into the back, including infants and children. Their elders sat on the hoods or bumpers or else stood and watched. I could see more walking up the dirt road that swooped down the bluff to the distant town, well over a kilometer away at the low shore.

Rosalía saw me looking. “They came to see,” she said.

“I suppose it’s big news, people coming from nowhere.”

“Not to see you,” she scolded me. “They came to see Abuelita. Because she said you would come.”

The little crowd was transfixed. And silent. As if in utter awe. The sun was beginning to set and it lit their faces in orange relief, faces weathered from a life outdoors. Their island was beautiful but bleak, a scrub desert in the midst of a deep, sky-blue sea. The village below was an uneven cluster of a hundred or so dwellings made of stucco or simple concrete whose windows had no glass. There was one general store, no larger than a gas station convenience shop, and one restaurant. Most people fished or worked in the small fish processing plant near the dock, where all work was done by hand. Other than the seasonal surfers who came for the waves off the southeast shore, it was the tiny island’s only industry. The bright, white-walled lighthouse stood by itself above the rest.

“You are tired maybe and want to rest,” Rosalía said. “There is a bathroom through there. I will make some food.”

“Thank you,” I said, perplexed at her manner. She wasn’t hesitant or resentful, and yet, something was clearly bothering her. By the looks of the place, the girl and her grandmother were far from wealthy, and I hoped my companions knew enough to eat whatever was given them.

We were led around the corner to a long room that had no wall on the courtyard-facing side. I counted six metal bunks, all empty. At one end was an open-doored toilet with shower and two stalls. We each took turns. The water smelled of rust, but it was good to wipe the sweat and dirt of Everthorn off our hands and faces.

Outside, the huddled crowd remained, although I suspected its membership had changed. I found Rosalía in the kitchen. The narrow pantry had no door. I had been right. It was not well-stocked. There didn’t seem to be a refrigerator. Our host was stirring a pot on an electric stove over which dried chiles had been hung. There was a single picture of St. Francis on the wall. I smelled fish and spices.

“Thank you,” I said. “Your hospitality is . . . well, it’s unexpected.”

Rosalía kept stirring. She didn’t even turn.

I stepped into the kitchen. “If we’re intruding, please just say. I know your grandmother is sick. If there’s a boat or something to the mainland, we’d be—”

“I should have believed her,” she said.

“Believed?” I sat at the four-seat kitchen table and waited for more. When none came, I told her that her English was very good.

“Thank you.” She glanced back and smiled ashamedly, as if just remembering her manners. “I don’t get to practice so much. But I watch American TV sometimes. We have a TV,” she said.

“English is not my first language either,” I said. “Listening is easier than making your own sentences, isn’t it?”

“Si.” She looked out the window over the sink to her left. From there, you could see the water. “We used to come here when I was young.” She motioned around the scrub land.

“Oh?”

“I didn’t like it. My mother took us. She said ‘Abuelita won’t leave the lighthouse, so we will go to her.’ I thought it was stupid. I wanted to go back to America, not use my vacation to play in the dirt.” She smiled ruefully at her younger self. “But Abuelita was right. All this time.” She turned to me. “You are here.”

“She said we would come?”

Rosalía looked out at the ocean again. The sun had disappeared over the horizon, which glowed with the last light of the day. There was very little light pollution there, which meant the night would be dark, as it used to be all across the world. The sky was clear. We would see the Milky Way.

“The way my mother told me,” Rosalía said, “Abuelita was not a very pretty girl. When she was a teenager, one of the boys in the village asked to marry her. My grandmother told my mother that he was a very mean boy and no one liked him and he thought Abuelita would be the only girl to have sex with him. She was very excited to be married. So were my great-grandparents. I don’t think they thought anyone would marry her either. My great-grandfather had always wanted to be an artist, so to celebrate the news, he painted a . . .” She scowled and tried to think of the word. She traced a square in the air. “A cabinet for clothes.”

“Dresser,” I said.

“Yes. A dresser. They were very poor, so furniture was a nice wedding gift. It was an old furniture with many damages and he covered it with many colors, including the face of his daughter on the front. He was very proud and showed everyone from the back of his truck. My mother said many people made jokes and when the boy heard them and saw the painting of his bride, he changed his mind and left the village. I don’t know if that’s true, but that’s what everyone say. Abuelita was very sad and ran away.”

“How old was she?”

Rosalía thought for a moment. “Maybe 15 or 16. This was in Coahuila. Near Durango. My grandparents were from there.”

“What happened?”

“My mother said Abuelita ran into the desert and found a big scorpion and tried to get it to sting her.”

She stopped there as if to let me draw the right conclusion, but I had already understood. The young woman wanted to die. She preferred to be remembered for her tragic death in the desert over her life as the ugly girl no one would marry.

“Did it sting her?” I asked.

“She said so. But she did not die. My great-grandfather found her two days later. She was not awake. She was hot and sick. But my grandmother, Abuelita’s older sister, nursed her. When she woke up, she . . .” Rosalía stopped. She turned to me. “This part is very silly. Old people sometimes believe silly things.”

“Yes, we do.” I smiled.

“You are not so old,” she told me.

“Something wonderful happened, didn’t it?”

She nodded. “Abuelita said the scorpion spoke to her. She said he was not a scorpion. He was Huehuecóyotl, the coyote, in disguise. He said he had angered the Moon with his tricks and was hiding in the rocks until morning. He told her that he would give her what she wanted, but since it was wrong to do suicide, she had to do one good thing first. And then death could take her. She said he stung her then, in the neck, but the doctors, they never found a mark.”

“They thought she was delirious.”

“Yes. But she believed it. She believed it very much. She told everybody who would listen about what Huehuecóyotl had showed her. My mother said the other kids thought she was saying lies to make herself seem special and not to be the ugly girl no one wanted. Life in the village was hard for Abuelita then. My grandmother married and my great-grandfather died and there was nothing for her, so she left. I’m not sure when she found this lighthouse. My mother probably told me, but I forgot. But I know they wouldn’t give her the job right away. The government didn’t give jobs to women in those days. She camped out on this land for many days. She cleaned fish and worked little jobs in the town for money. The old man who lived here tried to chase her away, but she wouldn’t leave. My father said she was a prostitute also, but I don’t think so. My father never liked Abuelita. He thought she was strange. Everyone did.”

“But she got the job.”

“She had to work very hard. And it took a long time. My mother tells many stories about how she would not give up. She was the lighthouse keeper’s assistant first. Abuelita says she was just a housekeeper and cook. The old man convinced the Baja government that he needed her, and they paid a little money, but he kept it. That is why she was allowed to stay. So he could get money. She did all the work and he did nothing but sit on the veranda and drink beer. When he finally died, times had changed and a woman could have a job. I only knew her then, when she was keeper of this lighthouse.”

“I noticed all the beds,” I said.

Rosalía nodded. “Many woman came. One time, when Abuelita worked for the old man, there was a girl in the town who was beaten very badly by her father. She had laid with her boyfriend, I think, and was not married, so her father beat her and chased her away and she had nowhere to go. Abuelita let her hide in the storage room. When the old man found her, he was very angry. ‘This girl cannot stay here,’ he yelled. ‘She cannot eat our food.’ But Abuelita was not afraid. She knew she would live to do her one good thing. Huehuecóyotl had told her—only then could death take her. So she pushed the old man and yelled back. My mother said she waved a broomstick. Always she was cleaning, so she had the broomstick. The old man was angry but he was too lazy to do anything. When the girl was better, Abuelita took money from the old man, money she had earned, and put the girl on a boat to Baja. Wherever she went, the girl told everyone about the fearless woman of the lighthouse.”

“And other women came,” I said.

Rosalía nodded. “Some from as far as México City. They came to escape their men, who could not sneak onto this island without all the fishermen knowing, so they were safe here. Many were pregnant or had small children. Abuelita was very strict to them. They had to pray to Mary. No drugs or alcohol. I got into big trouble maybe five years ago because I brought cerveza on our visit.” She paused. “It was very stupid. It made Abuelita very mad.”

“But she forgave you.”

“She never stopped believing. All these years.” She shook her head. She sniffed as she stirred the pot, which seemed to be some kind of fish stew.

“How long has she been here?”

“Almost sixty years. And she told everyone, ‘I have to stay. I have to be ready when the demon comes.’ When she got sick, she begged my mother to send me. ‘Someone has to watch the door,’ she said. Since I am the youngest, and I have no job and no family, I had to go. I think my mother always felt sorry for Abuelita—that she had no family.”

“But she did have a family,” I said. “I saw the pictures.”

Rosalía nodded again. She was still in shock, I could tell. Not just because three strangers and a monster had appeared from nowhere. Not just because her great-aunt had predicted it decades before. But because of what it meant for that old woman in the bed.

“I should be with her,” she said suddenly. She turned to leave and dropped the wooden spoon she had been using.

“I’ll get it.” I jumped up.

Reddish broth had splattered, and I got a towel. I heard the young woman scamper across the gravel of the courtyard. I picked up the spoon and washed it. I turned the burner down to a simmer and covered the pot. There were fresh vegetables to cut, and I cut them. Fresh tortillas were wrapped in a damp towel.

I thought about all the pictures in the bedroom, all the old woman’s grand-nieces—some by blood, some by faith. Huehuecóyotl the trickster, whose name means “old, old coyote,” had pulled another trick. A great many women were saved by the girl who tried to kill herself in the desert. If he had told the teenager that such a life waited, it wouldn’t have deterred her from her aim. So he burdened her with purpose. He told her she had to wait and do one good thing first. It was a lie. But it was the truth.

rough cut from the fifth and final course of my full-course occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. Part One is available now. The epic urban fantasy concludes next year with Part Two.

cover image by Tz’utuhil Mayan artist Diego Isaias Hernández Méndez