Rick Wayne's Blog, page 26

March 2, 2020

(Art) The Strange Uniformity of Madness

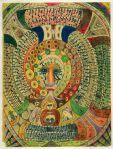

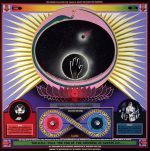

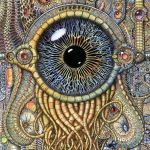

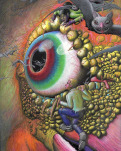

After discovering Posadism and the “Amok” dispatches, which is the most engrossing book catalog you will ever read, I recently got sucked into the art and philosophy of the ectocultures (my term). I don’t mean the Occupy movement or Anonymous, but the real deviants, people who either were (or maybe should’ve been) institutionalized. There is almost no coherent categorization, except that they’re all highly conspiratorial, anti-rational, and often invoke alien or demonic powers (or both).

Despite this complete heterogeny of thought, however, the art all has a distinctive style, often blending handwritten words and phrases — which bend and turn with the image — into extremely colorful, often diagram-like visual manifestos designed to convey truths, like the love for one’s parents, that can only be got at secondhand.

I’ll share some examples so you can spot the similarities.

These are works by Adolf Wölfli. From Wikipedia: “Wölfli was born in Bern, Switzerland. He was abused both physically and sexually as a child, and was orphaned at the age of 10. He thereafter grew up in a series of state-run foster homes. He worked as a Verdingbub (indentured child labourer) and briefly joined the army, but was later convicted of attempted child molestation, for which he served prison time. After being freed, he was re-arrested for a similar offense and in 1895 was admitted to the Waldau Clinic, a psychiatric hospital in Bern where he spent the rest of his adult life. He was very disturbed and sometimes violent on admission, leading to him being kept in isolation for his early time at hospital. He suffered from psychosis, which led to intense hallucinations.

At some point after his admission Wölfli began to draw. His first surviving works (a series of 50 pencil drawings) are dated from between 1904 and 1906.

Walter Morgenthaler, a doctor at the Waldau Clinic, took a particular interest in Wölfli’s art and his condition, later publishing Ein Geisteskranker als Künstler (A Psychiatric Patient as Artist) in 1921 which first brought Wölfli to the attention of the art world.”

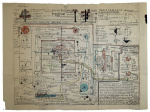

A similar but looser style can be found in the works of Jean Perdrizet, a Frenchman who “was a combat engineer in Grenoble, then at Électricité de France from 1944 to 1949. Around 1955 he started to invent prototypes and draw plans of machines to communicate with the ghosts or aliens : an ‘electric ouija,’ a ‘thermoelectronic net for the ghosts,’ a ‘Robot cosmonaut,’ ‘space scale,’ an ‘imagination cursor,’ a ‘flying pipe.’ He also invented a universal language, the so-called ‘T language.’ He sent his studies to NASA, CNRS and the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences.”

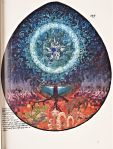

Next are works by Paul Laffoley. Again from Wikipedia: “He attended the progressive Mary Lee Burbank School in Belmont, Massachusetts, where his draftsman’s talent was ridiculed by his abstract expressionist teachers. After attending Boston public schools for a short time, Laffoley matriculated at Brown University, graduating in 1962 with honors in classics, philosophy, and art history. Laffoley has written that he was given eight electroshock treatments after the termination of ‘about a year of weekly sessions with a psychiatrist, who had treated me for a mild state of catatonia’ while at Brown in 1961.

In 1963, he enrolled at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he apprenticed with the sculptor Mirko Basaldella before being dismissed from the institution. In a search for expanded opportunities, Laffoley came to New York to work with the visionary Frederick Kiesler, and was recruited by Andy Warhol, who wanted someone to watch television for him at all hours of the night. Laffoley watched television in the pre-dawn hours, before programming had actually begun.

By the late 1980s, Laffoley began to move from the spiritual and the intellectual, and evolved to the view of his work as an interactive, physically engaging psychotronic device, perhaps similar to architectural monuments such as Stonehenge or the Cathedral of Notre Dame and their spiritual aura.”

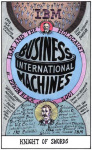

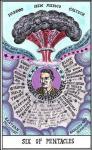

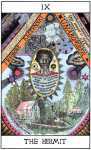

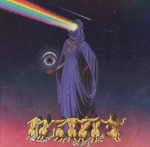

Next we have selections from a tarot deck by author Suzanne Treister created to accompany her book HEXEN 2.0, a sequel to HEXEN 2039, wherein she laid out a vision of the future based on the “interconnected histories of the computer and the Internet, cybernetics and the counterculture, science-fiction and scientific projections of the future, government and military research programmes, social engineering and ideas of the control society; alongside diverse philosophical, literary and political responses to the advance of technology including the claims of anarchoprimitivism, technogaianism, and transhumanism” (Amazon). The deck features, among other things, Timothy Leary as The Magician, Robert Oppenheimer as the Six of Pentacles, and Ada Lovelace as the Queen of Cups.

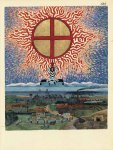

Interestingly, we seem the same style develop in Liber Novus (also called “The Red Book”) by Carl Jung, a man who was not by any reasonable definition mad but who did spend an inordinate amount of time swimming in his own subconscious. Indeed, Jung seems a bit too preoccupied with coloring inside the lines, which suggests a man who’s seen madness but returned.

Perhaps there’s something to it after all…

March 1, 2020

(Fiction) On Every Planet I Have Lived

On every planet I have lived, and in every time, there have always been women chasing the broken wastrel.

They make no secret of it. In fact, the more a man sings of his pain, or writes bad poetry – and the more people hear it – the more falsely cocksure he is, the more compulsive, the more addicted, then the higher the bounty she can claim.

For the trauma must always be in greater proportion to her own, lest it fail to serve its purpose, as if it were possible to grow one garden by tending another.

After a time, when her youth has faded and she can no longer command a high crop, she will tire of her sterile toil and seek a man whose garden is well fruited, and thence populate her own barren plot with seeds and cuttings until his is not half what it was.

Seek not, my son, such women as these, for there are ample others. Though she be less susceptible to your flatteries, oftentimes less comely, her deficits will match your surpluses, and contrariwise the same.

Seek her in places high and low, where she will often be reading or otherwise keeping her own company. Do not sing of your weaknesses, but do not hide them either. Rather, provide her reason to notice your strengths. Do good, such that you may be a candle to the beneficent.

And do not – ever – consort with liars, even those not maliciously so. She may call it innocent, a game of hide-and-seek with her self, the setting of a travail through which you must pass to discover the secret flower at her heart.

But no matter how enchanting, a cavalier woman is reckless and shifting, and can do naught but pour ruin over your soul.

-advice from the Grand Dame of Alturth to her grandson on the occasion of his father’s cruel murder at the hands of the Asteroid Witch

Prior to these last few years, when I learned to yoke it, whatever inspiration befell me landed in a digital junk drawer: character names, half-birthed premises, fragments of books that would never be written, such as this, which I came across yesterday while looking for something else.

cover image by Michal Dziekan

February 28, 2020

In literature as in love, we are astonished at what is chosen by others. —Andre Maurois

February 27, 2020

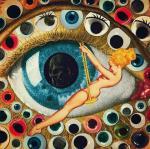

(Update) Eye’m Wishing

[image error]

Another periodic update to my ongoing collection The Eyes Have It, Eye Spy, Eye Always Feel Like, Eye Drank What?, and Eye Wonder.

February 24, 2020

(Art) The Techno-anarkist Idols of Alexey Egorov

[image error]

Russian artist Alexey Egorov paints dark technological marvels as nightmares or religious icons, alternating between fear and veneration. Find a great deal more by the artist on his ArtStation page.

February 23, 2020

(Curiosity) Voting for Darth Vader

[image error]

Celebrities don’t exist. Not really. They are characters in a public drama, which is why, whenever someone meets them — or rather, the person of the same name who plays them — there’s always an exclamation of difference: the Hollywood sweetheart who’s not a stuck-up cow (or who actually has a brain), the action hero who’s five inches too short for his ego, the comedian who’d rather not crack a joke for you while grocery shopping.

We can only be surprised at how normal they are if we never actually thought of them as real in the first place. Our encounter exposes the truth that the person we met is not the characterization of them on TV.

Every celebrity, from sports to politics, exists only inside the prison of our expectations. When one of them tries to escape, when a comedian asserts his pain in public, we resist! How dare they break character! Actions that would elicit sympathy in real life bring derision instead. We don’t want these people to be human, full of grimaces and contradictions. If they’re not gods, then their foibles are petty rather than tragic, their opulence disgusting rather than heroic, and we turn away.

This was made internationally patent twice recently, first when Prince Harry and his wife expressly rejected the roles that had been reserved for them (new ones were quickly invented), and second in the dramatic plot twist in the epic of Kobe Bryant.

In politics, we do not root for Trump or Sanders (or whoever). We root for the character of the same name. That there also exists a real person is incidental. We participate in a politician’s triumphs and failures as we do Sherlock Holmes’ — as played by Benedict Cumberbatch the famous actor, as played by Benedict Cumberbatch the real person.

In the language of drama, the villain is that which must be vanquished for the community to flourish, as indeed Darth Vader is. He burns with his Empire, despite being redeemed.

No one roots for the villain. It isn’t even that he’s despicable. We know from the beginning that Darth Vader will lose. It’s just a question of how. Rooting would be pointless.

But politicians (and sports teams) can be both hero and villain. People really do root for the character Trump or the character Sanders as they do not for the character Darth Vader.

But they are not the same character. The Sanders I support is not the one you revile. He can’t be, for in one story, he’s trying to save the country, and in the other, to destroy it.

Even the very facts of his life, as distilled by the media, are not the same. One episode from Sanders’ life proves him a champion of justice; another, a hypocrite. One episode from Trump’s life proves he’s an evil genius; another, a buffoon.

Politics is often likened to a horse race, but in fact it’s worse than that. It’s much closer to daytime television than to racing. Politics has regularly scheduled seasons, for example (in the US, they last exactly two years), with cliffhanger endings. The politicians, as the political philosopher Bernard Williams noted, are characters in a soap opera invented on our behalf:

They are called by their first names or have the same kind of jokey nicknames as soap opera characters, the same broadly sketched personalities, the same dispositions to triumphs and humiliations which are schematically related to the doings of the other characters. When they reappear, they give the same impression of remembering only just in time to carry on from where they left off, and they equally disappear into the script of the past after something else more interesting has come up.

If you can’t understand why anyone would support Trump — or Sanders, or AOC — consider the truth: no one does. The villain in your story is a completely different character than the hero of someone else’s. Neither bear much relation to the truth.

Even their failures, universally recognized, are alternatively comic or tragic, depending on which political opera you follow. Politicians are just as chained to our expectations as any other celebrity, which is why they spend so much time courting appearances.

When we read an opposing side’s opinion piece, it sounds nonsensical because it is a chapter from a book we’re not reading inserted into our own as if by misprint.

The reason we throw it into the trash is the same reason we get angry at actors and comedians for breaking character. To understand someone’s else’s opera we must first leave our own.

cover image by Aleksandr Nikonov

February 21, 2020

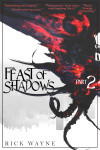

New Covers!

[image error]

I wasn’t satisfied with my covers for FEAST OF SHADOWS, so I went back to the drawing board. I think it was worth it.

[image error]

Part 1 (with the old cover still) is available here.

February 17, 2020

(Art) The Surreal Landscapes of Gediminas Pranckevičius

[image error]

Lithuanian artist Gediminas Pranckevičius makes utterly stunning surreal landscapes of stone minds and impossibly stacked houses, where shadowy sea creatures prowl like phobias inside wall-less seas and we each live inside a house made of self.

February 16, 2020

(Curiosity) A Short History of Decay

With how many illusions must I have been born in order to be able to lose one every day!

E.M. Cioran was a Romanian thinker who spent most of his life in France. This week, I finally finished his 1949 tomb of Western culture, “A Short History of Decay,” which is one of the most challenging—and therefore rewarding—books I’ve read.

It has no genre. It is part philosophy, part poetry, part diary, part literary trolling. What it depletes with bullshit—and fair warning: there is plenty of that—it rejuvenates with poetry. It is, as the title suggests, a pessimist’s manifesto. But rather than one tiresome groan, Cioran serves it in bites and gnashes: page-long missives that read like entries in an insomniac’s journal, with titles like Abstract Venom, The Model Traitor, Defense of Corruption, and The Refusal to Procreate.

Look at your body in a mirror: you will realize that you are mortal; run your fingers over your ribs as though across a guitar, and you will see how close you are to the grave. It is because we are dressed that we entertain immortality: how can we die when we wear a necktie?

“A Short History of Decay” is not for beginners. It’s rife with allusion—one long gag on Western culture. Cioran’s fits will make no sense unless you know what he’s swallowed. I had to read half the passages twice and roughly a third sent me to the dictionary. They are packed obliquely, like the accumulations of a literary hoarder, and if I could hack through ten pages in a day, I considered it good progress.

For the effort, the reader is rewarded rather than converted. There is no argument here, nothing rightly called analysis, although certain themes reemerge: history as progress, the consolations of philosophy, and the possibility of salvation are all repeatedly proposed and rejected.

Having passed through so many lungs, the air no longer renews itself. Every day vomits up its tomorrow, and Everything is an ordeal: broken down like a beast of burden harnessed to Matter, I drag the planets . . . Thus one discovers the Sage and the Decadent in oneself, a predestined and contradictory cohabitation: two characters suffering the same attraction for passage, the one of nothingness toward the world, the other of the world toward nothingness.

Lyrically fatal, raging with indifference, solipsistic, burning with quotable lines, “A Short History of Decay” is an agony of bibliophilia marked, in warning, For Readers Only.

Special acclaim should be given to the book’s translator, Richard Howard, who is a poet of at least as much grace as the author for rendering the work so eloquently in English.

Everything we do not participate in seems unreasonable. Since the direction of our thoughts is not that of our hearts, we sustain a secret inclination for all that we trample down . . . All gall conceals a revenge and is translated into a system: pessimism—that cruelty of the conquered who cannot forgive life for having deceived their expectations.

A civilization evolves from agriculture to paradox. Between these two extremes unfolds the combat of barbarism and neurosis; from it results the unstable equilibrium of creative epochs . . . Must we take history seriously, or stand on the sidelines as a spectator? Are we to see it as a struggle toward a goal or the celebration of a light which intensifies and fades with neither necessity nor reason? The answer depends on our degree of illusion about man, on our curiosity to divine the way in which will be resolved that mix of waltz and slaughterhouse which composes and stimulates his becoming.

The devil pales besides a man who owns a truth . . . If we put in one pan all the evil the “pure” have poured out upon the world, and in the other the evil that has come from men without principles and without scruples, the scale would tip toward the first. There is more mildness in vice than in virtue, more humanity in depravity than austerity.

We change cures, finding none effective, none valid, because we have faith neither in the peace we seek nor in the pleasures we pursue… Theology, ethics, history, and everyday experience teach us that to achieve equilibrium there is not an infinity of secrets; there is only one: submit.

There is more than one resemblance between begging for a coin in the city and waiting for an answer from the silence of the universe.

What surrounds us we endure better for giving a name.

(The following odd equations do not appear in the book so mundanely as in a list. They are peppered throughout. I have merely gathered a few.)

God: a perpendicular fall upon our fear

The Universe: geometry stricken with epilepsy

Life: a fit of lunacy throttling matter

Destiny: in the vocabulary of the vanquished, an unknown law

History: a factory of ideals

Man: a dust infatuated with ghosts

Culture: pyrotechnics against a night sky of nothingness

Prejudice: an organic truth

Bureaucracy: a metaphysics designed for monkeys

Health: decisive weapon against religion. Invent the universal elixir: the heavens will vanish and never return. No use seducing man by other ideals: they will be weaker than diseases.

[image error]Agnès Varda, Enfants masqués, 1953

February 14, 2020

(Art) Maps of the Unreal

It is the fantastic lands that are more real, more present. The Europeans in love with darkest Africa were in love with a fiction. One only travels to real places for facts or money. They are the dust on our shelves from which we pull the realer still.