Rick Wayne's Blog, page 27

February 12, 2020

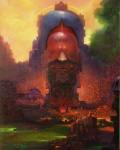

(Art) The Pulp Drama of Ferenc Pinter

[image error]

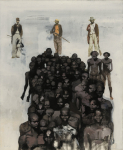

Ferenc Pinter (1931 – 2008) was an Italian painter and illustrator. He was born in Liguria to a Hungarian father and Italian mother. His name was spelled Pintér Ferenc in Hungarian and he signed most of his works with the Hungarian name order; however in Italy he was known as Ferenc Pintér. In 1940 his family moved to Budapest where his father received health treatments. After being orphaned, Pinter tried to enter the Academy of Fine Arts, but he was not admitted for his divergence with the communist ideas of the time. After the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, he fled to Italy. In Milan, he was commissioned for a series of advertisement illustrations and posters until, in 1960, he began working with the large Italian publishing house Mondadori, with which he collaborated for 32 years.

Pinter realized numerous covers for Mondadori books and magazines, such as Segretissimo (a spy stories series, 14 covers), Diabolik, Maigret and Agatha Christie translations, and for Oscar Mondadori (the most sold Italian pocket series). In 1989 he painted the 22 Tarot Triumphs by Lo Scarabeo of Turin. [Wikipedia]

I do love cover art. Pinter certainly showed that you don’t need a lot of content to make a compelling image.

February 10, 2020

(Art) The Hyperspace Colors of Paul Lehr

[image error]

Paul Lehr (1930-1998) studied illustration at the prestigious Pratt Institute. His first sf cover – for the American edition of Jeffery Lloyd Castle’s Satellite E One (1954) – is a realistic depiction of the construction of an unusually-shaped Space Station, and similar images of spacecraft, rendered mostly in shades of grey, are seen in other early covers. His cover for Robert Sheckley’s Journey Beyond Tomorrow (1962) show Lehr moving toward the less representational style that would later be his trademark.

His first noteworthy work in this vein, perhaps, was his cover for James Gunn’s Future Imperfect (1964), depicting a Medusa-like woman and a human-headed spider amidst odd designs within a rectangle that is partially shattered. His covers for a 1967 edition of H G Wells’s The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth (1904) and Sheckley’s Dimension of Miracles (1968) display what became one of his trademarks, strange egg-shaped objects, here broken to respectively reveal an enormous eye and an array of planets and stars. While his people often seem small and insignificant in contrast to the large structures dominating his covers, Lehr could also make effective use of bright pastel colours, which tended to make his covers stand out amidst others dominated by darker hues.

As American publishers came to prefer more realistic art in the 1980s, Lehr focused instead on covers for the sf magazines Analog, Omni, Tomorrow: Speculative Fiction, and Weird Tales as well as covers for foreign publishers. Lehr also worked outside the genre for magazines like Business Week, Fortune, Life, Playboy, The Reader’s Digest, and Time, and he remained active until his death in 1998. [SF Encyclopedia]

February 9, 2020

(Fiction) The Shotgun in the Bathroom

I could tell it was serious by the tone of her voice.

Lieutenant Miller called me to her office where Craig Hammond, my old partner, was waiting in one of the chairs. His block head had a little less hair than when we started running homicides together. But other than that he was basically the same.

“Craig.” I shut the door behind me.

“Hari,” he replied. “How’s it going?”

“I suspect you know.”

He nodded once.

Most of the guys I came up with had morals with square edges and were proud of it. Thing is, time on the job tends to beat on square edges. If you’re hollow, you’ll bend and turn crooked. Craig Hammond wasn’t like that. His time on the job hadn’t bent him, just blunted his edges. And rounded his waistline.

I stood behind the remaining open chair as Miller took her seat.

She came right out with it. “I’ve given the tape to Detective Hammond. He’ll be running the case from here.”

I raised my eyebrows. “That was quick.”

“What do you mean?”

“Is this my punishment for the Landry case?”

Lt. Miller sat with excellent posture like she did when she wanted to assert herself without being threatening. I turned to Craig. He was expressionless. I sat down.

“We got the fingerprint report,” she said. “From the tape.”

We.

Normally that stuff goes directly to the officer in charge—namely, me. But these went to my lieutenant first.

I wondered what else was going on behind my back. “And?”

“No matches. However, the return address—”

“Floral Park,” I said.

“Yes.” She nodded.

“It was Alexa Sacchi’s house,” Hammond added. “It’s where the family was living when she disappeared.”

Alexa Sacchi had gone missing at fifteen. It had been seven years since anyone had seen her. It didn’t make any sense. Either she’d sent me—a person she’d never met—a VHS tape out of the blue, or someone wanted me to think she had.

I was scowling. “I worked that case originally.”

“So did Detective Hammond,” Miller said.

“And you trust him to do a better job of executing?”

“Call it professional distance.”

Miller knew I was repeatedly checking out Alexa’s necklace from storage. I could guess how that looked—like I was holding on to the case, as happens to detectives sometimes, and had lost objectivity.

“Craig and his new partner—” She looked to him for the name.

“Rigdon,” he answered.

“—bring the same prior experience but also a fresh pair of eyes. And since you have a full caseload—”

“I’m sure they do, too.”

She just looked at me. She didn’t have to say it. I had blamed my “mishandling” of the Landry case, the Gold Bullet Killer as she was now known, on an overly full plate. Miller wasn’t letting me get away with that. It made her department look bad.

“Clear your Jane Doe. What’s her name?”

“Amber Massey.”

“Let go of some of your cold cases. Then we’ll talk.”

I nodded in understanding.

“In the meantime, please brief Detective Hammond on what you have so far. I imagine the two of you have a lot to talk about.”

She said it as if there was more to the comment. Hammond stood and nodded.

I looked between them for a moment. Miller didn’t mean about Alexa Sacchi. She didn’t mean the VHS tape or my being taken off the case. She meant Hammond and I, old partners, needed to talk about my personal situation—the one with Kent Cormack and Dr. More.

I stood and walked out. I wasn’t angry so much as just confused. Well, that’s not true. I was a little angry. But Craig and I knew each other well, and Miller giving the case to him was nothing but a hassle. It didn’t change anything but who did the paperwork. If anything, he got the worse end of the deal.

He followed me in his loping gait down the stairs.

“My treat,” he said.

We walked in silence down the street and around the corner to our favorite little kosher deli. It still had the original 1950s layout, with barely enough room to walk between the long counter, lined with fixed stools, and the narrow two-seaters affixed to the side wall. Each table sported the same cluster of bottles: old-style catsup, spotted mustard in a jar, and the best homemade relish in the city. It was the middle of the afternoon, so there was plenty of space. We sat at the back, near the bathrooms, and ordered coffee.

“Lemme see it.” He smiled at my mouth.

I curled my lip and let him see my missing tooth. I tongued it. First bicuspid, upstairs on the right side.

He chuckled. “Get clocked kickboxing?”

“Rugby,” I said.

“Rugby? But it was kickboxing before, right?”

“It’s called Muay Thai.”

The waitress set the coffees down, spilling a little of mine. I reached for a napkin.

Hammond blew on the hot liquid in his cup. “Ah, right. And what was it before that?” He took a gurgling sip.

I wiped the table and poured the cream. “CrossFit.”

“So what does rugby have that those other things don’t?”

“Who says there has to be anything?”

“You keep cutting your hair shorter.”

I fought the urge to touch it. “Whereas you . . .” I took a sip of my coffee and nodded to his waist.

He patted it. “Excellent detective work.”

It was good to see him. It had been a while.

He could tell I wanted the pleasantries out of the way already. “Go easy on Miller, huh? She’s worried about you. We both are.”

“This about Miller?”

“No. It’s not.” He sat back in his chair as a new patron squeezed past to sit at the counter a few seats down. “But she’s doing you a favor. She made it clear the department’s fixing to hang you out over this thing, if only to cover their ass. You’re gonna hafta fight, Har. Hard.”

I nodded.

“So how bad is it?” he asked.

“She didn’t show you the file?”

He shook his head. “Just a verbal summary. Something about a history of epilepsy. Voices. Hallucinations?” He raised his eyebrows in query. “Miller said there was something about a wolf with three eyes or something like that?” He waited for an explanation.

“It was a long time ago.”

“She said the wolf thing was—”

“I meant the stuff from before. I was never diagnosed with epilepsy. I was never diagnosed with anything. I hit puberty and my body wigged out. I was in a hospital for a while. I was 13.”

He shook his head and sat back. “And then?”

I shrugged. “It stopped. The docs said maybe it was something to do with hormones. Our preacher was sure it was the devil.”

“What do you think it was?”

“I don’t. I don’t think about it. Not any more than I think about pimples or school dress codes. That was almost thirty years ago, man. Men convicted of first-degree murder then are looking to get out soon.”

I could see him studying my face, trying to decide if he believed me.

“No,” I answered the unspoken question. “It never happened again. Not until last year.”

“So it just came from nowhere?”

“Dunno. Gettin’ old maybe.”

“Miller said the doc thinks it was stress.”

I made a face. “Yeah, I heard that. And yes, we were under stress. It was a gang house. Salvadorans. I was there to arrest a suspect I’d been after for two months. Guy was into Santeria in a big way. You should’ve seen what he did to people. But it’s not like you and I haven’t been in half a dozen situations way worse than that.”

He nodded in understanding, looking down at his coffee. “The shotgun.”

Neither of us would ever forget it.

“Honestly, the shit with Cormack was pretty routine,” I explained. “I was at the door. We were about to move. Next thing I know, I’m on the ground, convulsing. Cormack and the others went in.”

I paused. “And I wasn’t there to clear my side of the house. Cormack got shot. Face all messed up. Never gonna walk again.”

Craig let me go at my own pace. He sat there and listened.

“When they found me, I was flat on my back. Did you hear that? Drool on my face.” I took another sip. “I didn’t even remember where I was at first. They said I was speaking in tongues.”

“Tongues?”

“That’s what they called it. Not baby noises. More like gibberish words. I said I was fine but they took me to the hospital. I saw Kent when they brought him in. They’d tried to stabilize him at the scene, I guess, so I beat him there. There were transfer stains all over from where the techs had gotten his blood on them and then brushed or touched something. With all those little smears, it looked like he’d been run through a wood chipper. He had a plastic breather on his face. Tubes coming out of every orifice. After a while, his wife showed—”

“That’s enough,” he stopped me.

I took another sip. The mug was thin and the coffee was already getting tepid.

He turned his cup in a circle. “You should’ve come to me.”

“And say what? That it’s my fault Kent Cormack won’t ever walk again? You’d just tell me I was full of shit.”

“Because you are.”

The waitress left the bill upside down on the table as she passed.

I shrugged. “See? I wasn’t wrong.”

“No, you’re not wrong, Har. It’s just funny how every time the shit hits it, the best course of action also happens to be the one where you deal with everything completely on your own.”

“Come on . . . I’m not cutting you out of anything here. It’s precisely because we’re friends that I didn’t want to get you involved. Nothing good is gonna come from any of this and you know it. What kinda friend am I if I let any bit of that rub off on you? You have a wife and two beautiful girls whereas I—” I stopped.

“Yeah.” He rubbed both his eyes with one hand. His thumb and forefingers made circles around his lids. “Jesus, same ol’ Hari.” He was almost laughing in frustration.

I took another sip and pushed the cup away. “Miller seems to think assigning the case to you closes me out. That true?”

“Fuck.” He gave me a sarcastic look. “Of course not. But that doesn’t mean we don’t have to play this close to the chest. Now is not the time for you to be bucking orders up and down the hall.”

It also wasn’t the time to argue with him. “Fine. So how do you wanna play it?”

“I’ll hafta run point.” He jutted a finger toward me accusingly. “That’s not negotiable. But . . . I’ll tell you whatever I find. And I’ll use you when I can. Fair enough?”

I nodded. He knew I didn’t think so, but there was nothing for me to say right then.

I shifted in my seat so I could get up in the tight space without knocking anything over.

“I was actually thinking about that fucker with the shotgun the other day,” he said, looking at the oblong scar on the back of his hand.

“Oh?” I settled back into my chair.

“I never cared you were gay, you know.”

“What does that have to do with anything?”

“But lots of guys did.”

“Lots of guys still do.”

“Which makes it a pain in the ass for anyone who has to work with you, you know that.”

I opened my mouth and he raised a hand defensively and cut me off. “I know it’s not the same,” he said. “I’m not saying that. I’m just saying, it’s still shit and I had plenty of reasons for picking someone else. But then there was that guy . . . Christ. Who the hell keeps a shotgun in the bathroom?”

We chuckled.

“It’s not like he knew we were coming, right? Couple hours before, we didn’t even know we were gonna be there.” He shook his head. “But out he came. Pants down. Big ol’ beard. Dick still dripping pee. Sawed-off in his hands.” His smile faded and he got serious. “If that had gone any other way, one of us woulda wound up like Kent Cormack.”

“Or worse,” I said.

“Or worse,” he repeated. “I keep thinking about what would’ve happened if the door to the bedroom had been closed. I wouldn’t have been able to dive outta the way. Same for the radiator. It’s not like that drywall woulda stopped anything. Not at that range.”

“You got burned, right?”

He nodded. “There was that chime of metal on metal, and a crack, and a jet of steam hit my hand. Third-degree burn. Boiled in my own skin. And then it was over. Just like that. Seconds.” He snapped his fingers.

We didn’t say anything for a minute.

He sighed and took a drink. “I stepped to the door with my sidearm and peered around and you were already cuffing the fucker and reading him his rights.”

“Why do you think I let you go first?” I joked.

He leaned forward. “You wanna know a little secret?”

I scowled.

“I almost shat myself.”

“What?”

He nodded with a chuckle. “It’s true. That whole time we were there, I had a turd hanging halfway outta my ass. I had to hold that damned thing for three hours. I couldn’t use the bathroom in the apartment. It was a crime scene. And I knew if I ran off somewhere, you and the other guys would put two and two together. So the whole time we processed everything and the photographers took pictures and we took the suspects downtown and debriefed the captain, I was squishing a little turtle head between my cheeks.”

Now it was my turn to let him go at his pace.

“From then on, as far as I was concerned those fuckers could say whatever they wanted. I wanted you watching my back. Two days later I made the request. And I never regretted it, Har. Never.”

“Why do I feel there’s a ‘but’ coming?”

“But you’re stubborn as shit. And selfish.”

“Selfish?”

“Yes. Selfish. When did you decide people were a strange conundrum you can’t be bothered to figure out? You spend all your time catching up on . . . on—” He struggled to find the words. “Talismans and voodoo and shit.”

“Santeria.”

“And don’t tell me that isn’t the pendant from the Sacchi case.” He motioned to the little silver amulet dangling from my wrist.

I moved it under the table. “How does that make me selfish?”

“Look.” He backed off. “I don’t wanna fight. Okay? All I’m saying is, don’t piss away your career for Kent fucking Cormack.” He squinted in disgust. “It was his case and his raid. He should’ve had twice as many guys covering that house and you know it. And you know why he didn’t, too. As far as a lot of us are concerned, that corrupt piece of shit got exactly what he deserved.”

“Maybe,” I said, getting up from the booth. I took out my wallet and laid a ten on the table. “But his wife and kid didn’t.”

rough cut from my five-course occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS. Part One is available now. The epic urban fantasy concludes this spring with Part Two.

cover image by Micah Ulrich

[image error]

February 7, 2020

(Art + Fiction) Visions of the Labyrinth

[image error]

In classical Western myth, the labyrinth, in which the Minotaur stalked, is symbolic of the universe, of the search for God, or our psyches, while the Minotaur himself — half man, half bull — is symbolic of our bestial selves.

But which half? In pre-Christian culture, the bull was associated with heaven, as it still is in India. The Queen of Crete, who gave birth to the Minotaur, had sex with a bull, but she was driven to it by a god, Poseidon. So which half is bestial, and which half divine?

This is the question, or one of them, that Borges asks in his wonderful short story, The House of Asterion.

The House of Asterion

Jorge Luis Borges (In Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings, ed. Donald A. Yates and James E. Irby, London: Penguin. pp. 170-172)

AND THE QUEEN gave birth to a child who was called Asterion.

I know they accuse me of arrogance, and perhaps misanthropy, and perhaps of madness. Such accusations (for which I shall exact punishment in due time) are derisory. It is true that I never leave my house, but it is also true that its doors(whose numbers are infinite) (footnote: The original says fourteen, but there is ample reason to infer that, as used by Asterion, this numeral stands for infinite.) are open day and night to men and to animals as well. Anyone may enter. He will find here no female pomp nor gallant court formality, but he will find quiet and solitude. And he will also find a house like no other on the face of this earth. (There are those who declare there is a similar one in Egypt, but they lie.) Even my detractors admit there is not one single piece of furniture in the house. Another ridiculous falsehood has it that I, Asterion, am a prisoner. Shall I repeat that there are no locked doors, shall I add that there are no locks? Besides, one afternoon I did step into the street; If I returned before night, I did so because of the fear that the faces of the common people inspired in me, faces as discolored and flat as the palm of one’s hand. the sun had already set, but the helpless crying of a child and the rude supplications of the faithful told me I had been recognized. The people prayed, fled, prostrated themselves; some climbed onto the stylobate of the temple of the axes, others gathered stones. One of them, I believe, hid himself beneath the sea. Not for nothing was my mother a queen; I cannot be confused with the populace, though my modesty might so desire.

The fact is that that I am unique. I am not interested in what one man may transmit to other men; like the philosopher I think that nothing is communicable by the art of writing. Bothersome and trivial details have no place in my spirit, which is prepared for all that is vast and grand; I have never retained the difference between one letter and another. A certain generous impatience has not permitted that I learn to read. Sometimes I deplore this, for the nights and days are long.

Of course, I am not without distractions. Like the ram about to charge, I run through the stone galleries until I fall dizzy to the floor. I crouch in the shadow of a pool or around a corner and pretend I am being followed. There are roofs from which I let myself fall until I am bloody. At any time I can pretend to be asleep, with my eyes closed and my breathing heavy. (Sometimes I really sleep, sometimes the color of day has changed when I open my eyes.) But of all the games, I prefer the one about the other Asterion. I pretend that he comes to visit me and that I show him my house. With great obeisance I say to him “Now we shall return to the first intersection” or “Now we shall come out into another courtyard” Or “I knew you would like the drain” or “Now you will see a pool that was filled with sand” or “You will soon see how the cellar branches out”. Sometimes I make a mistake and the two of us laugh heartily. Not only have I imagined these games, I have also meditated on the house. All parts of the house are repeated many times, any place is another place. There is no one pool, courtyard, drinking trough, manger; the mangers, drinking troughs, courtyards pools are fourteen(infinite) in number. The house is the same size as the world; or rather it is the world. However, by dint of exhausting the courtyards with pools and dusty gray stone galleries I have reached the street and seen the temple of the Axes and the sea. I did not understand this until a night vision revealed to me that the seas and temples are also fourteen (infinite) in number. Everything is repeated many times, fourteen times, but two things in the world seem to be repeated only once: above, the intricate sun; below Asterion. Perhaps I have created the stars and the sun and this enormous house, but I no longer remember.

Every nine years nine men enter the house so that I may deliver them from evil. I hear their steps or their voices in the depths of the stone galleries and I run joyfully to find them. The ceremony lasts a few minutes. They fall one after another without my having to bloody my hands. They remain where they fell and their bodies help distinguish one gallery from another. I do not know who they are, but I know that one of them prophesied, at the moment of his death, that some day my redeemer would come. Since then my loneliness does not pain me, because I know my redeemer lives and he will finally rise above the dust. If my ear could capture all the sounds of the world, I should hear his steps. I hope he will take me to a place with fewer galleries fewer doors. What will my redeemer be like? I ask myself. Will he be a bull or a man? will he perhaps be a bull with the face of a man? or will he be like me?

The morning sun reverberated from the bronze sword. There was no longer even a vestige of blood. “Would you believe it, Ariadne?” said Theseus “The Minotaur scarcely defended himself.”

February 6, 2020

(Fiction) Babylon Eternal

The old ones are patient, and not so easily fooled.

After the death of Solomon, wisest of rulers, the kingdom of the Hebrews was distributed equitably among his heirs, who distrusted each other as mightily as their father was wise. Swiftly they fell, with many other lands, to the conquerer, Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. As was his practice, the new king took hostage every male youth, both high-born and . . . . . . were marched east to study the Chaldean sciences—what the Hebrews called ‘the black arts’—in the hopes that a whole generation would be converted to the Babylonian faith and return to the lands of their ancestors to marry, multiply, and so to erase without bloodshed the famously fanatical cult of Yahweh. For above all, Nebuchadnezzar desired a Babylon eternal and would brook no rivals.

It was one of these sons of Abraham, a boy named Daniel . . . with . . . excelled at his studies above . . . and was allowed to interpret the king’s dreams, an honor normally reserved for the High Priest of the Temple of Marduk. So impressed was Nebuchadnezzar that he dismissed his ministers’ objections and kept the young man’s counsel day and night, walking with him through the hanging gardens he had built to please his fickle queen . . . had barely noticed them. The king no doubt disliked what he heard, for Daniel referred to him as ‘the destroyer of nations’ and said Nebuchadnezzar’s own kingdom, his great and unprecedented legacy which surpassed even the mighty empires of Sumeria, would crumble and fall and be supplanted by mightier empires still, over and over, until at last a pinnacle was reached, a precipice from which the world itself would tumble back into darkness. Such was the arrogance and folly of the course the king charted.

The Book of Daniel is full of prophecies like that, some as opaque as a pale mirror. It’s only with . . . You can believe Daniel was a charlatan, or you can believe that his vagary was intentional, that he had witnessed something so terrible, so frightening, he dared not say it outright. For in truth, Nebuchadnezzar was vexed by visions beyond reason . . . He prayed to his gods first, as all men do. He prayed to the sky god Marduk, who had slain the many-headed dragon and so forged civilization out of chaos. He prayed to Enki and Ishtar and Enlil. But the gods and goddesses of Babylon were as silent as their stone-walled temples, as still as their marble-faced statuary, and the king despaired.

In righteous anger, Nebuchadnezzar demanded his priests call upon different gods, older gods still whose names had passed from memory but whose crypts could still be found deep under the twice-ancient cities of Ur and Uruk. And so archaic seals were broken and relic hymns were sung and fresh sacrifices made numbering in the . . . of thousands, and a narrow portal was forged, no wider than a pinprick such that no evil could slip through, and across it, the old gods, whose names were blighted by men, were summoned in parlay.

After a gap of thirteen days, they answered, and a deal was struck. The Nameless, the ancient lords of the earth, promised the king that his beloved Babylon would never die. He had only to record a tome, which would be whispered to him, one chapter at a time, over a period of six days and six hours and six minutes—a gift to all mankind from the emperors of the high dun.

The king agreed and set . . . as an infliction . . . But Nebuchadnezzar was no fool. He knew that which was whispered to him was nothing less than a return to ancient bondage, the architecture of eternal night. So he locked himself inside his treasury, the most secure vault yet constructed, there to trick the tricksters. He honored his bargain but recorded the tome in a language that had never been spoken: its alphabet, his own devising; its grammar, allegory; its syntax, so recursive and arcane that he had hope it might never be deciphered. And when finally he emerged, shrunken and disheveled, to test his invention before the wisest men of his court, he found there were none who could decipher it, not even the brilliant Daniel, and Nebuchadnezzar rested, believing he had . . .

But even a king is human, and in the years that followed, Nebuchadnezzar could not easily forget the murmurings he had heard in the dark, nor the strange and abominable recipes he had transcribed into a stillborn tongue. In the end, history records that King Nebuchadnezzar went mad and took his own life and . . . There is no mention, by Daniel or any others, of the book he composed while locked away, feverishly scratching until his reed split and his fingers cracked and his own blood flowed as ink. . . . but they knew of it, and its dark purpose. That is why Daniel had called the king ‘the destroyer of nations.’ It was why he filled his eponymous chronicle with cryptic warnings about the end of days. For he dared not speak the truth. He dared not reveal to the world that such a book existed. For in the king’s madness, the Book of Shadows, as it was called, had disappeared . . .

As for Babylon, she is the name long given to decadence, which rules everywhere.

—translated from the German by Reinhardt Stolz

rough cut from my five-course occult mystery, FEAST OF SHADOWS

cover image by Nekro

February 5, 2020

(Curiosity) Simon Stålenhag and the Science Fiction of ‘Hold My Beer’

[image error]

As my beta readers work through the manuscript of Part 2 of FEAST OF SHADOWS and my editors does what she can ahead of their feedback, my brain continues to wrestle with the project I’ve been calling SCIENCE CRIMES DIVISION, although that will not be the title.

In describing it to a friend this weekend, they thought it was going to be absurdist, like a cyberpunk Douglas Adams book, and were skeptical, and after some frustrated backtracking, I realized it’s nearly impossible to effectively communicate a vision for anything that doesn’t have a clear precursor.

This is the logic of the concept pitch. You take a project that was already successful and introduce a twist. After Die Hard came innumerable knockoffs, each succinctly describable as “Die Hard on a boat” or “Die Hard on a plane” or “Die Hard on a plane with snakes,” and so on.

Any brief description of something not expressly derivative, such as the original Star Wars, sounds completely ludicrous: a psychic monk with a laser-sword and his apprentice join a teenage princess and a smuggler with a sentient dog to stop an evil galactic empire from unleashing their planet-killing doomsday weapon. Hearing that, you might expect something like Buck Rogers.

Clearly, what made Star Wars awesome wasn’t a novel premise or characters. In fact, Lucas pilfered most of the characters and plot from a black-and-white Kurosawa film called The Hidden Fortress. And by 1977, laser blasters, robots, light-speed ships, interstellar gangsters, and the rest were all standard sci-fi tropes. What’s more, those tropes were lifted directly from adventure fiction of the pulp era. One could argue that Star Wars, at its heart, is a Western. Tatooine even looks the part.

What made Star Wars awesome was that it combined all of that in a new way, a way that wasn’t campy. Same for the original Tim Burton Batman (which is campy by today’s standards but which was a big departure at the time).

Stories with a novel, readily outlandish premise, like Sharknado, almost always have little else going for them. Don’t believe me? Go do a quick review of the movies on your TV’s rental app. Not that we can’t enjoy Sharknado ironically. Of course we can. But that movie is trying to be something different than Star Wars, or Dune.

Incidentally, this is why every seasoned writer silently and internally rolls their eyes when someone grabs their arm and says “Hey, I have this great idea for a story.” What makes a story great isn’t the premise. It’s the execution. (That’s why it’s so hard.)

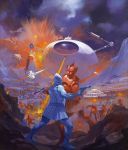

I’m not sure a pithy pitch would really capture the vision I have for my unnamed project, AKA SCIENCE CRIMES DIVISION, but the closest I’ve seen to it so far are the paintings of Simon Stalenhag, below. I want to write a story that takes the accessibility of technology to its logically absurd conclusion.

Most scifi starts with the 1950s-era assumption that technology, as a function of science:

A) fundamentally (and only) benefits mankind, and/or

B) if it’s dangerous or abusable, remains under the control of the social regime.

Unless it’s expressly a prototype, all fictional technology works. In fact, it often works for that which is wasn’t designed. Every episode of Star Trek involves the engineering team re-purposing the engine or the sensor arrays to do something they were never designed to do.

And yet, consider that across more than 40 years of life, I’ve never once owned a printer that worked without fault.

The paradigm for most science fiction is nuclear technology, which still requires some advanced physics to understand and manipulate, and, more importantly, a state apparatus — funding and a defensive infrastructure — to collect, retain, and refine the necessary fissile material.

In the three-quarters of a century since they were invented, only ten countries have developed nuclear weapons: the US, Russia, the UK, France, China, Israel, South Africa, India, Pakistan, and North Korea. Another eight have (or had) access, either through NATO or as a result of being a former Soviet republic: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Turkey, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine.

Another dozen or so countries, including Japan, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia, probably could develop the technology if they wanted but have been kept from doing so generally by fear of nuclear proliferation and specifically by an international anti-proliferation regime administered by the United Nations.

To date, no individual or private entity has been known to possess nuclear weapons (although I’ve said for years that it would be a fundamental test of the Second Amendment if Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos were to purchase one).

To illustrate why this matters, consider the virile Captain Dirk Thrusterd and his crew, who, while investigating a fatal accident at a mining colony on planet Albion-IX, uncover a plot by the invading alien Xicxz’t to detonate a black hole device inside our solar system. With all long-term communications jammed, Captain Thrusterd and his intrepid crew are alone. Only they can save the Terran Alliance!

In the early chapters, we might be told that the colonists on Albion-IX, which has an acid atmosphere, survive on “genetically modified” crops which they grow in domed hydroponic factories. In fact, that might figure into the plot when the alien saboteur, who has been surgically altered with nanotechnology to resemble a human, traps the captain and his love-interest — a sexy scientist who escaped to the remote colony only to forget the captain and their torrid but interrupted romance — inside one such dome, which is slowly leaking atmosphere!

To escape, the clever captain uses some sheet plastic and an oxygen tank to rig a makeshift hazard suit while the sexy scientist uses fertilizer pods to make a bomb. After blowing a hole in the wall, they use the makeshift suits to reach a nearby airlock. When the scientist’s is damaged in the blast, the captain gives her his own and suffers acid burns and spends the rest of the book emotionally aloof from her, convinced she could never love a man with such rugged and deadly-looking scars. But of course she’s pure of heart, and pressing her ample bosoms to his chest, she confesses her love at the end, after he saves the entire human race, thereby abrogating any need for him to say (or even be aware of) his feelings, which he’s suppressed since the tragic death of his parents.

All of that is bog-standard. In fact, they did something very much like it in the first Guardians of the Galaxy movie. But consider for a moment the technology of this world. Just from the first act, we know there are FTL drives, FTL communication, genetic engineering, nanotechnology, and black hole bombs — probably with a bunch of other things as well, like handheld blasters and plucky robotic-AI sidekicks.

The black hole bomb is a clear stand-in for nuclear weapons and may require the analogous state apparatus to produce. In fact, there may only be the prototype, which the good captain secures for the people of earth at the end, thereby ensuring at least a temporary deterrent — if they use it on us, we can use it on them. (That stalemate will falter at the beginning of the sequel, forcing the captain to once again choose his loyal crew — and the human race — over his ample-bosomed lover, who will nevertheless remain faithful as she waits for him even through the entirely unnecessary cliffhanger ending that sets up the third book.)

But even if people in this universe can’t generally make black holes, all the supporting tech that goes into the prototype will be available, along with everything else mentioned — portable power cells for blaster weapons, tools to genetically engineer living organisms, AI, and nanotech, all of which is evidently portable enough (and economical enough) to ship off to some distant world without much thought. And if miners on some distant colony have it, then you better believe there is at least a thriving black market.

The way stories like this get around having to deal with technology “leaking” into non-military society (while maintaining suspension of disbelief) is to ignore it or to assert control by the social regime, which uses it only for good, or for defense.

Returning to the world of Star Trek, for example, the Federation, however benevolent, is a centrally-planned state that retains a legal monopoly on literally everything. No one is allowed to have anything they can’t use responsibly. If a technologically-inferior race gets ahold of a transporter device, or a complement of photon torpedoes, the Federation will send an armed starship to take it back. And everyone is meant to adhere to the Prime Directive, even where that means watching millions of sentient creatures die from some horrible plague that could easily be cured.

So, too, in the world of virile Captain Thrusterd, where the Xicxz’t threat demands humanity be governed by a virtuous and nominally apolitical military dictatorship plucked right out of ancient Greece (ignoring that such regimes had very mixed records even where they only had to administer a bronze age archipelago populated in the thousands, versus an interstellar community of billions).

The fact is, if genetic engineering exists, people will use it for all kinds of nefarious and silly things. And I don’t simply mean rich people making sure their kids are the smartest and prettiest, although that too. A dude in a garage somewhere will ask someone to hold his beer while he gives his dog — or himself — an eight-foot penis, just for shits and giggles.

It’s funny really that this is where the genre has ended up given that the first fully-formed work of science fiction, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, was written to warn us about exactly that kind of dude experimenting in his garage.

I imagine a fictional world where there is such a controlling authority but where it is actually struggling to hold on. It is also, like any potentially potent bureaucracy, often abusive of its power, leading some people to question whether we wouldn’t be better off without it — that is, until something crazy happens, like a zombie plague, or the temporary cessation of gravity.

I imagine a fictional world full of absurd expressions of technology, of fads and scams and ridiculous consumer products that never work right (or for long), a world where people go on doing the best they can, including solving a murder that may or may not have been committed with new technology.

The end result, hopefully, is something that is first and foremost FUN, with a background full of outrageous events that you nevertheless could just believe might happen…

I’m not trying to predict the future with this story. I’m not a futurist and don’t want to be. I’m trying to tell a fun story that reveals through its exaggerations something about the contradictions and absurdity of the modern condition — where we all blissfully hand over our privacy in return for our daily dose of memes.

At this stage, I’m just floating ideas. One I really liked — as a background event rather than a key plot point — is that cities can lease anti-grav generators and will occasionally “turn off” (which is to say, dramatically lower) gravity in certain areas for some window of time, usually to complete expensive earth-moving projects, such as a new freeway or cross-town tunnel, that, when complete, theoretically benefits everyone.

That means some folks get a letter in the mail similar to today, where instead of having no water or power from noon to six on Wednesday, there will be almost no gravity, and there’s a nice color pamphlet explaining what that means and how to prepare. Symbolically, it’s a statement about how technology is turning our life upside down.

Use of that technology is controversial since its first use resulted in catastrophe, and now the earth’s gravity fluctuates locally, like its weather, and people get up every day to watch the gravity forecast in addition to the weather.

I imagine a pod of large herbivorous dinosaurs grazing on the weeds of an abandoned Wal-mart. Someone resurrected and released them (one of the events that led to the passing of the STCA), and they’ve just become part of the world.

But this isn’t Jurassic Park. The animals will proliferate, for example, given that they can push through conventional crop barriers. A cull will be introduced, with environmentalists objecting that it’s unethical and pointing out that the animals didn’t ask to be created, but now that they existed, they were fundamentally no different than, say, whales. Property owners will ask what rights extinct animals even had, and that they’re fundamentally an invasive species, out of time rather than out of place, and so on.

I see traffic being backed up at the government shuts down the freeway to move a giant military robot on an 8-lane-wide flatbed.

I see zombies as an endemic rather than epidemic threat. Most people are inoculated, so those that do show up — always assumed to be some anti-vaxxer getting his just desserts — are little more than a nuisance, and there are city workers who have to go retrieve them, like a deer carcass on the side of the road.

I see the world placing strong restrictions on sentient robots, so there are relatively few of them, and they tend to keep to themselves and be very naturopathic and spiritual, like hippies. It’s rumored they can do magic.

And so on.

In North America, threats are investigated by the Science Crimes Division of the Science Control Agency, the enforcement and paramilitary wing of the US Department of Education.

Simon Stålenhag and the Science Fiction of ‘Hold My Beer’

[image error]

As my beta readers work through the manuscript of Part 2 of FEAST OF SHADOWS and my editors does what she can ahead of their feedback, my brain continues to wrestle with the project I’ve been calling SCIENCE CRIMES DIVISION, although that will not be the title.

In describing it to a friend this weekend, they thought it was going to be absurdist, like a cyberpunk Douglas Adams book, and were skeptical, and after some frustrated backtracking, I realized it’s nearly impossible to effectively communicate a vision for anything that doesn’t have a clear precursor.

This is the logic of the concept pitch. You take a project that was already successful and introduce a twist. After Die Hard came innumerable knockoffs, each succinctly describable as “Die Hard on a boat” or “Die Hard on a plane” or “Die Hard on a plane with snakes,” and so on.

Any brief description of something not expressly derivative, such as the original Star Wars, sounds completely ludicrous: a psychic monk with a laser-sword and his apprentice join a teenage princess and a smuggler with a sentient dog to stop an evil galactic empire from unleashing their planet-killing doomsday weapon. Hearing that, you might expect something like Buck Rogers.

Clearly, what made Star Wars awesome wasn’t a novel premise or characters. In fact, Lucas pilfered most of the characters and plot from a black-and-white Kurosawa film called The Hidden Fortress. And by 1977, laser blasters, robots, light-speed ships, interstellar gangsters, and the rest were all standard sci-fi tropes. What’s more, those tropes were lifted directly from adventure fiction of the pulp era. One could argue that Star Wars, at its heart, is a Western. Tatooine even looks the part.

What made Star Wars awesome was that it combined all of that in a new way, a way that wasn’t campy. Same for the original Tim Burton Batman (which is campy by today’s standards but which was a big departure at the time).

Stories with a novel, readily outlandish premise, like Sharknado, almost always have little else going for them. Don’t believe me? Go do a quick review of the movies on your TV’s rental app. Not that we can’t enjoy Sharknado ironically. Of course we can. But that movie is trying to be something different than Star Wars, or Dune.

Incidentally, this is why every seasoned writer silently and internally rolls their eyes when someone grabs their arm and says “Hey, I have this great idea for a story.” What makes a story great isn’t the premise. It’s the execution. (That’s why it’s so hard.)

I’m not sure a pithy pitch would really capture the vision I have for my unnamed project, AKA SCIENCE CRIMES DIVISION, but the closest I’ve seen to it so far are the paintings of Simon Stalenhag, below. I want to write a story that takes the accessibility of technology to its logically absurd conclusion.

Most scifi starts with the 1950s-era assumption that technology, as a function of science:

A) fundamentally (and only) benefits mankind, and/or

B) if it’s dangerous or abusable, remains under the control of the social regime.

Unless it’s expressly a prototype, all fictional technology works. In fact, it often works for that which is wasn’t designed. Every episode of Star Trek involves the engineering team re-purposing the engine or the sensor arrays to do something they were never designed to do.

And yet, consider that across more than 40 years of life, I’ve never once owned a printer that worked without fault.

The paradigm for most science fiction is nuclear technology, which still requires some advanced physics to understand and manipulate, and, more importantly, a state apparatus — funding and a defensive infrastructure — to collect, retain, and refine the necessary fissile material.

In the three-quarters of a century since they were invented, only ten countries have developed nuclear weapons: the US, Russia, the UK, France, China, Israel, South Africa, India, Pakistan, and North Korea. Another eight have (or had) access, either through NATO or as a result of being a former Soviet republic: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Turkey, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine.

Another dozen or so countries, including Japan, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia, probably could develop the technology if they wanted but have been kept from doing so generally by fear of nuclear proliferation and specifically by an international anti-proliferation regime administered by the United Nations.

To date, no individual or private entity has been known to possess nuclear weapons (although I’ve said for years that it would be a fundamental test of the Second Amendment if Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos were to purchase one).

To illustrate why this matters, consider the virile Captain Dirk Thrusterd and his crew, who, while investigating a fatal accident at a mining colony on planet Albion-IX, uncover a plot by the invading alien Xicxz’t to detonate a black hole device inside our solar system. With all long-term communications jammed, Captain Thrusterd and his intrepid crew are alone. Only they can save the Terran Alliance!

In the early chapters, we might be told that the colonists on Albion-IX, which has an acid atmosphere, survive on “genetically modified” crops which they grow in domed hydroponic factories. In fact, that might figure into the plot when the alien saboteur, who has been surgically altered with nanotechnology to resemble a human, traps the captain and his love-interest — a sexy scientist who escaped to the remote colony only to forget the captain and their torrid but interrupted romance — inside one such dome, which is slowly leaking atmosphere!

To escape, the clever captain uses some sheet plastic and an oxygen tank to rig a makeshift hazard suit while the sexy scientist uses fertilizer pods to make a bomb. After blowing a hole in the wall, they use the makeshift suits to reach a nearby airlock. When the scientist’s is damaged in the blast, the captain gives her his own and suffers acid burns and spends the rest of the book emotionally aloof from her, convinced she could never love a man with such rugged and deadly-looking scars. But of course she’s pure of heart, and pressing her ample bosoms to his chest, she confesses her love at the end, after he saves the entire human race, thereby abrogating any need for him to say (or even be aware of) his feelings, which he’s suppressed since the tragic death of his parents.

All of that is bog-standard. In fact, they did something very much like it in the first Guardians of the Galaxy movie. But consider for a moment the technology of this world. Just from the first act, we know there are FTL drives, FTL communication, genetic engineering, nanotechnology, and black hole bombs — probably with a bunch of other things as well, like handheld blasters and plucky robotic-AI sidekicks.

The black hole bomb is a clear stand-in for nuclear weapons and may require the analogous state apparatus to produce. In fact, there may only be the prototype, which the good captain secures for the people of earth at the end, thereby ensuring at least a temporary deterrent — if they use it on us, we can use it on them. (That stalemate will falter at the beginning of the sequel, forcing the captain to once again choose his loyal crew — and the human race — over his ample-bosomed lover, who will nevertheless remain faithful as she waits for him even through the entirely unnecessary cliffhanger ending that sets up the third book.)

But even if people in this universe can’t generally make black holes, all the supporting tech that goes into the prototype will be available, along with everything else mentioned — portable power cells for blaster weapons, tools to genetically engineer living organisms, AI, and nanotech, all of which is evidently portable enough (and economical enough) to ship off to some distant world without much thought. And if miners on some distant colony have it, then you better believe there is at least a thriving black market.

The way stories like this get around having to deal with technology “leaking” into non-military society (while maintaining suspension of disbelief) is to ignore it or to assert control by the social regime, which uses it only for good, or for defense.

Returning to the world of Star Trek, for example, the Federation, however benevolent, is a centrally-planned state that retains a legal monopoly on literally everything. No one is allowed to have anything they can’t use responsibly. If a technologically-inferior race gets ahold of a transporter device, or a complement of photon torpedoes, the Federation will send an armed starship to take it back. And everyone is meant to adhere to the Prime Directive, even where that means watching millions of sentient creatures die from some horrible plague that could easily be cured.

So, too, in the world of virile Captain Thrusterd, where the Xicxz’t threat demands humanity be governed by a virtuous and nominally apolitical military dictatorship plucked right out of ancient Greece (ignoring that such regimes had very mixed records even where they only had to administer a bronze age archipelago populated in the thousands, versus an interstellar community of billions).

The fact is, if genetic engineering exists, people will use it for all kinds of nefarious and silly things. And I don’t simply mean rich people making sure their kids are the smartest and prettiest, although that too. A dude in a garage somewhere will ask someone to hold his beer while he gives his dog — or himself — an eight-foot penis, just for shits and giggles.

It’s funny really that this is where the genre has ended up given that the first fully-formed work of science fiction, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, was written to warn us about exactly that kind of dude experimenting in his garage.

I imagine a fictional world where there is such a controlling authority but where it is actually struggling to hold on. It is also, like any potentially potent bureaucracy, often abusive of its power, leading some people to question whether we wouldn’t be better off without it — that is, until something crazy happens, like a zombie plague, or the temporary cessation of gravity.

I imagine a fictional world full of absurd expressions of technology, of fads and scams and ridiculous consumer products that never work right (or for long), a world where people go on doing the best they can, including solving a murder that may or may not have been committed with new technology.

The end result, hopefully, is something that is first and foremost FUN, with a background full of outrageous events that you nevertheless could just believe might happen…

I’m not trying to predict the future with this story. I’m not a futurist and don’t want to be. I’m trying to tell a fun story that reveals through its exaggerations something about the contradictions and absurdity of the modern condition — where we all blissfully hand over our privacy in return for our daily dose of memes.

At this stage, I’m just floating ideas. One I really liked — as a background event rather than a key plot point — is that cities can lease anti-grav generators and will occasionally “turn off” (which is to say, dramatically lower) gravity in certain areas for some window of time, usually to complete expensive earth-moving projects, such as a new freeway or cross-town tunnel, that, when complete, theoretically benefits everyone.

That means some folks get a letter in the mail similar to today, where instead of having no water or power from noon to six on Wednesday, there will be almost no gravity, and there’s a nice color pamphlet explaining what that means and how to prepare. Symbolically, it’s a statement about how technology is turning our life upside down.

Use of that technology is controversial since its first use resulted in catastrophe, and now the earth’s gravity fluctuates locally, like its weather, and people get up every day to watch the gravity forecast in addition to the weather.

I imagine a pod of large herbivorous dinosaurs grazing on the weeds of an abandoned Wal-mart. Someone resurrected and released them (one of the events that led to the passing of the STCA), and they’ve just become part of the world.

But this isn’t Jurassic Park. The animals will proliferate, for example, given that they can push through conventional crop barriers. A cull will be introduced, with environmentalists objecting that it’s unethical and pointing out that the animals didn’t ask to be created, but now that they existed, they were fundamentally no different than, say, whales. Property owners will ask what rights extinct animals even had, and that they’re fundamentally an invasive species, out of time rather than out of place, and so on.

I see traffic being backed up at the government shuts down the freeway to move a giant military robot on an 8-lane-wide flatbed.

I see zombies as an endemic rather than epidemic threat. Most people are inoculated, so those that do show up — always assumed to be some anti-vaxxer getting his just desserts — are little more than a nuisance, and there are city workers who have to go retrieve them, like a deer carcass on the side of the road.

I see the world placing strong restrictions on sentient robots, so there are relatively few of them, and they tend to keep to themselves and be very naturopathic and spiritual, like hippies. It’s rumored they can do magic.

And so on.

In North America, threats are investigated by the Science Crimes Division of the Science Control Agency, the enforcement and paramilitary wing of the US Department of Education.

February 4, 2020

(Art) The Noir Underworlds of Josh Courlas

[image error]

Josh Courlas is a New York-based digital artist who creates mysterious scenes out of an Adventuretime-like noir underworld, a dark video game of idols and edifices before which tiny figures hold lights. Like the work of Dawid Planeta and others, it is a variant of a new genre of art I have written about before: the casual hierophany.

I discuss the possible social and historical significance of this eruption and give numerous examples from the realm of fantastic art in The Old Gods.

February 2, 2020

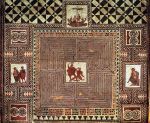

(Art) SHUNGA! The Japanese Art of the Woodblock Money Shot (NSFW)

A couple years ago, my buddy and I went to see an exhibit on shunga, traditional Japanese erotic art, mostly dating to the Edo and Meiji eras. The term shunga translates as “pictures of spring”, a euphemism for sex, and many of the works were similarly titled — “Placing the peach in the golden vase.”

It’s difficult to describe the Japanese attitudes toward sex. On the one hand, there were many more pictures of this type produced in Japan than similar works in Europe, and they were created by some of the greatest artists of the time, including Hokusai, whose famous wave off the coast of Mount Fuji is a global icon for the country.

On the other hand, sex is still considered somewhat “shameful,” and these pictures would not have been openly displayed in the home (as erotic art was in ancient Rome, for example). Consider that this very exhibit only took place after a successful curation at the British Museum — it was their idea — and that no major museum in Japan would host it. They all thought it disgraceful to show this art in public.

To see it, we had to schlep to the Eisei-Bunko Museum — Bunkyo is a ward in the city — a little archive in northern Tokyo that houses the documents and artifacts of the Hosokawa clan, one of the more important aristocratic families from the feudal era. Their regents were a little more daring.

Indeed, when I told my Japanese girlfriend I was going, she looked at me cockeyed and asked, “Do you like that?” I had to explain that I wasn’t secretly masturbating to 18th century Japanese woodblock prints in the bathroom.

Japanese views on sex are complex, and after several years and multiple visits dating back to 2001 — I was in Kyoto on 9/11 — I still can’t explain it very well. You can’t think in terms of our Victorian dichotomy: open or repressed. Sex is not repressed here. It is not a taboo subject for young people. Masturbation and pornography are occassionally mentioned on television. But it’s not “open” either. Rather, it’s a completely unique cultural expression with its own norms and mores.

Most of the works in the exhibit, like Hokusai’s (below), were woodblock carvings that were then used to make high quality prints, and it’s the prints that are on display rather than the work that actually came from the artist’s hand. (See video.)

“Manpuku Wagojin (The Gods of Intercourse)” (c.1821) is a series of shunga by Katsushika Hokusai

Besides woodblock prints, other mediums included paintings on silk, such as the one below, which has quite vivid colors not captured well in this scan. (Photography was forbidden at the exhibit, so I had to raid the internet.) There were also several paper scrolls and even large folding screen, such as you might change your clothes behind.

[image error]Painting on silk, one out of four similar kakemonos from a series named “Pleasure Competition in the Four Seasons.” This is Summer.

Most of the works were simple heterosexual couplings like this, but on display were depictions of homosexuality. Although that included some men, such as in the cover image to this post, which depicts a couple having sex in a public bath, most of the homosexual art was lesbian in nature and was probably to titillate heterosexual men, as today.

Also on display were threesomes, 69, cunnilingus, dildos (including strap-ons), money shots (with semen), bestiality (usually to some fantastic or divine purpose — think dreams or animal spirits), even a glory hole!

[image error]Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川 歌麿; c. 1753 –1806)

This picture was not on display, but I couldn’t find the picture of the big black strap-on that was there.

[image error]Ehon haikai yobuko-dori 会本拝開夜婦子取 (Haikai Book of the Cuckoo (or Worshipping a Woman’s Pussy at Night))

[image error]attributed to Tsukioka Settei (月岡雪鼎; 1710 – 1786)

And as always happens with sex, there was satire. The Hollywood porn industry certainly didn’t invent the sex-parody! This picture from the British Museum’s collection is a riff on the parinirvana of the Buddha — his death, many years after achieving Enlightenment — and so depicting it this way is analogous to nailing a penis to a cross, although this is more lighthearted than that would have been.

My buddy bought the book to the exhibit, which is printed in the traditional style, unbound on a long ream of accordion-folded paper. It’s massive and includes a great many more works than were on display in the small museum.

Despite all the shame and hoopla, there are signs that Japanese attitudes to shunga might be changing. Weeks after it opened, there are still long lines to see the exhibit. We had to wait thirty minutes just to get in. There were quite a few foreigners of course, but the crowd was overwhelmingly Japanese.

Here is a master printmaker demonstrating the fascinating, multi-step process of turning a series of woodcuts into a single gorgeous print.

SHUNGA! The Art of the Woodblock Money Shot (NSFW)

A couple years ago, my buddy and I went to see an exhibit on shunga, traditional Japanese erotic art, mostly dating to the Edo and Meiji eras. The term shunga translates as “pictures of spring”, a euphemism for sex, and many of the works were similarly titled — “Placing the peach in the golden vase.”

It’s difficult to describe the Japanese attitudes toward sex. On the one hand, there were many more pictures of this type produced in Japan than similar works in Europe, and they were created by some of the greatest artists of the time, including Hokusai, whose famous wave off the coast of Mount Fuji is a global icon for the country.

On the other hand, sex is still considered somewhat “shameful,” and these pictures would not have been openly displayed in the home (as erotic art was in ancient Rome, for example). Consider that this very exhibit only took place after a successful curation at the British Museum — it was their idea — and that no major museum in Japan would host it. They all thought it disgraceful to show this art in public.

To see it, we had to schlep to the Eisei-Bunko Museum — Bunkyo is a ward in the city — a little archive in northern Tokyo that houses the documents and artifacts of the Hosokawa clan, one of the more important aristocratic families from the feudal era. Their regents were a little more daring.

Indeed, when I told my Japanese girlfriend I was going, she looked at me cockeyed and asked, “Do you like that?” I had to explain that I wasn’t secretly masturbating to 18th century Japanese woodblock prints in the bathroom.

Japanese views on sex are complex, and after several years and multiple visits dating back to 2001 — I was in Kyoto on 9/11 — I still can’t explain it very well. You can’t think in terms of our Victorian dichotomy: open or repressed. Sex is not repressed here. It is not a taboo subject for young people. Masturbation and pornography are occassionally mentioned on television. But it’s not “open” either. Rather, it’s a completely unique cultural expression with its own norms and mores.

Most of the works in the exhibit, like Hokusai’s (below), were woodblock carvings that were then used to make high quality prints, and it’s the prints that are on display rather than the work that actually came from the artist’s hand. (See video.)

“Manpuku Wagojin (The Gods of Intercourse)” (c.1821) is a series of shunga by Katsushika Hokusai

Besides woodblock prints, other mediums included paintings on silk, such as the one below, which has quite vivid colors not captured well in this scan. (Photography was forbidden at the exhibit, so I had to raid the internet.) There were also several paper scrolls and even large folding screen, such as you might change your clothes behind.

[image error]Painting on silk, one out of four similar kakemonos from a series named “Pleasure Competition in the Four Seasons.” This is Summer.

Most of the works were simple heterosexual couplings like this, but on display were depictions of homosexuality. Although that included some men, such as in the cover image to this post, which depicts a couple having sex in a public bath, most of the homosexual art was lesbian in nature and was probably to titillate heterosexual men, as today.

Also on display were threesomes, 69, cunnilingus, dildos (including strap-ons), money shots (with semen), bestiality (usually to some fantastic or divine purpose — think dreams or animal spirits), even a glory hole!

[image error]Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川 歌麿; c. 1753 –1806)

This picture was not on display, but I couldn’t find the picture of the big black strap-on that was there.

[image error]Ehon haikai yobuko-dori 会本拝開夜婦子取 (Haikai Book of the Cuckoo (or Worshipping a Woman’s Pussy at Night))

[image error]attributed to Tsukioka Settei (月岡雪鼎; 1710 – 1786)

And as always happens with sex, there was satire. The Hollywood porn industry certainly didn’t invent the sex-parody! This picture from the British Museum’s collection is a riff on the parinirvana of the Buddha — his death, many years after achieving Enlightenment — and so depicting it this way is analogous to nailing a penis to a cross, although this is more lighthearted than that would have been.

My buddy bought the book to the exhibit, which is printed in the traditional style, unbound on a long ream of accordion-folded paper. It’s massive and includes a great many more works than were on display in the small museum.

Despite all the shame and hoopla, there are signs that Japanese attitudes to shunga might be changing. Weeks after it opened, there are still long lines to see the exhibit. We had to wait thirty minutes just to get in. There were quite a few foreigners of course, but the crowd was overwhelmingly Japanese.

Here is a master printmaker demonstrating the fascinating, multi-step process of turning a series of woodcuts into a single gorgeous print.