Rick Wayne's Blog, page 34

November 10, 2019

(Art) The Hyper-Real Dream Girl

Look closely at the cover image.

[image error]

Now this one:

[image error]

And finally this one:

[image error]

Georgian artist Irakli Nadar makes hyper-real digital portraits from photographs of models and celebrities.

“Hyperrealism” is a genre of art distinguished by its level of detail. The name was meant to distinguish it from the earlier genre of “photorealism,” which was born in the days before high-definition photography. But hyperrealism can also mean more than “high definition.” It can mean something that is “more than real.”

How is that possible? How can an image be “more human than human?” Because of our biology.

Most people know that baby birds “imprint” on a parent figure. After they are born, they find in their surroundings that which most resembles a parent in appearance or action and treat it as such.

This means they’re born with an innate sense of what a parent looks and acts like. Scientists have discovered that what is coded for in their DNA (and then in the animal’s nervous system) is not, in the case of ducklings, a photorealistic image of an adult duck. Rather, it is an abstract ducklike form.

For centuries, farmers in China have been exploiting this fact to recruit ducklings to their rice fields, where they help control the snail population. The farmers use a specially-shaped flattened stick which, to ducklings, looks like a parent, and they will follow it.

Scientists have reproduced this in the lab. And in fact, through experimentation, they have been able to create a shaped and colored stick that so exactly matches the innate image in the ducklings’ head that they will imprint on the stick over their actual parents when both are present.

In other words, to the ducklings, the shaped colored stick is more “parental” than their parents. It is more real than real. It is hyperreal.

Nor are birds the only animals that have this special period of imprinting. Mammals do as well, which includes humans. Psychologists have found we carry all kinds of innate impressions in fact. People all over the world tend to rate a face more beautiful, for example, if it has a high degree of bilateral symmetry.

Culture and individual taste can alter or amend these innate impressions of course, but they are there. What’s interesting about Nadar’s pictures, then, is not the level of detail or how well they match the photographs from which they were taken, but the manner and ways in which they are different, in which they are hyperreal, in which they more closely match our innate impressions of beauty.

If you found the woman in the cover image stunning, contrast Nadar’s hyperreal image with the original. Note the emphasis of the eyes, the de-emphasis of the nose, the rounding of the lips, the larger forehead, the unblemished skin, etc.

This is of course what the advertising industry exploits when, for example, they extend a model’s legs in Photoshop to unreal proportions and the result is more appealing — more “real” than reality.

This is not new, by the way. The ancient Greeks were masters. Nor did it only apply to women (although they do take the brunt of it in the modern era). The warrior below, while seemingly realistic, has been exaggerated in subtle ways. His trunk is elongated, giving a sense of power; the vertical grooves in his chest and back, which create contrast, are impossibly deep and long; the muscles of his groin are engorged and extend over the hip; etc.

[image error]

The Greeks wanted their gods and goddesses to be superhuman — more than real — just as we do. Chris Hemsworth was always conventionally attractive of course, but he looked considerably different as an Australian daytime TV star (already a high standard) than as the god of thunder.

[image error]

It matters because we are entering a time when the hyperreal will exit the world of forms, of art and imagery, and collide with the merely real.

[image error]

The image above is by Evan Lee. More below by Nadar:

November 8, 2019

Hatred, which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated, and this was an immutable law. —James Baldwin

November 7, 2019

(Art) The Magical Fortresses of Avant Choi

[image error]

The superbly named Avant Choi has a real knack for fantastical settings, particularly temples and magical fortresses — giant trees and cliffs with faces. Fnd some inspiration for your next novel or game. Lots more by the artist on his ArtStation page.

November 6, 2019

We live in a time when strange women distributing swords...

[image error]

We live in a time when strange women distributing swords no longer sounds like a completely ridiculous form of government.

art by Tiago Sousa

November 5, 2019

We jest, but this is about what it’s like anymore.

More ...

November 4, 2019

(Feature) The Cacophony Before A Deafening Silence (or, Science Fiction is Dead, Jim)

[image error]

Until the New Wave began in the middle 1960s, most science fiction was fundamentally “rationalist” in that the worlds it imagined were overwhelmingly built on rational principles.

This is true even if the story were about a point of failure in the system, like Asimov’s Foundation series, which is a parable about how to return — or from our standpoint, how to create — the world “as it should be.” What saves us is learning, prophetically preserved in a library by a saint of science, the discoverer of the laws of history.

The pulp era was certainly a time of looking forward to things “as they should be.” Anyone who lived through two world wars and a great depression can be forgiven for indulging dreams of a brighter future, and the magazines of the time obliged. They confidently predicted we would soon live in “The City of the Future” and make our food in “The Kitchen of the Future” — utopias of good design, completely sanitized and free from worry.

Whirlpool even proposed a robotic vacuum cleaner in 1959, part of a fully automated kitchen, controlled from a central console. If you watch the black-and-white infomercial at the link, it’s clear they didn’t once imagine the internet, but I think it’s also safe to assume that even if they had, they wouldn’t have imagined surveillance capitalism either.

Fiction is a reflection of society, and science fiction, as the language of the future, is a reflection of our unconscious assumptions about it. It was not by accident that the New Wave replaced the pulp era in the late 1960s, exactly when the rest of society was changing.

The middle of the 20th century is (thus far) the only liberal era in history, by which I mean the policies pursued were overwhelmingly liberal: women’s suffrage, racial integration, pensions, a basic social safety net, etc.

I’m talking here about sailing direction, by the way, not absolute position, which will trip some people up, but something always trips some people up.

In the US, the core of this era ran from the stock market crash of 1929, which inaugurated the New Deal, to the 1968 Democratic National Convention, which was famously a chaos.

Even the conservative administration of the time upheld the values of the New Deal consensus. To encourage capital investment over profit-taking, Eisenhower supported a high marginal income tax on both corporations and the wealthy. He forcibly integrated schools, created the interstate highway system, and coined the phrase “military-industrial complex,” which he warned us about in his farewell address.

But by the late 1960s, with the passage of Social Security, a minimum wage, banking reform, legal integration, and health care for the poor, the New Deal consensus had more or less achieved everything it set out to, and so it collapsed, a victim of its own success.

At the same time congress was contemplating what would become the last of the major social reforms, New Wave writers in the US and UK were consciously breaking from the pulp era and asking themselves where science fiction could go next.

With negligible exceptions (Wells, Stapledon and who?), nearly every science-fiction writer up to a very few years ago made one very hidden—and indefensible—assumption. They assumed that science changed; that the world changed; that everything you could imagine changed, except one thing. The human race.

—Frederik Pohl, 1965

What the New Wave and its progeny imaged was a multiplicity of worlds and, for the first time, new ways to be human in them.

Where Asimov and Clarke were significantly concerned with the points in the universe where everything was the same for all — that is to say, laws, not just of robotics but of time, space, and human history itself — writers like Ursula Le Guin, Samuel Delaney, and Philip K. Dick were imagining worlds of difference: alternate histories, alternate societies, altered states of consciousness, differences in gender and in the nature and perception of reality.

This was a radical break, and the mark it left was indelible. After the 1960s, everyone was free to imagine a different future, with or without blasters and rocket ships.

But just like the 1968 DNC, the New Wave movement collapsed, and for the same reason. There was simply nothing to unite so many disparate visions beyond a rejection of the past.

The following decade, amid the specter of stagflation, the English-speaking world lurched right again. Supply-side policy, which favors capital over labor, became the norm, and the 1980s saw a wave of deregulation under Reagan in the US and Thatcher in the UK. Taxes were cut on corporations and the wealthy at the same time that automation and foreign competition were erasing working class wage gains.

Just as Eisenhower is largely unrecognizable as a conservative today, liberal administrations of the conservative era, Clinton and Blair, were “Third Way,” or right-leaning centrists. Clinton’s achievements are all planks in a classic Republican Party platform: a balanced budget, welfare reform, and deregulation of the banks.

So it is, circa 1980, a new vision of the future appeared, a future of corporate greed run amok and technology as an enslaver rather than a liberator, a future of breaking laws rather than discovering them, of hacking computers and hacking the human body. Cyberpunk seemed to announce, just in case anyone had missed it, that the liberal era was dead.

Unlike in 1959, today there actually are commercially available robotic vacuum cleaners. It was revealed a year or two ago that Roombas secretly make maps of our homes and beam them back to the company, ostensibly for “product improvement” but of course we can assume for marketing as well, which includes making profiles of our private lives.

The humble tractor, symbol of honest labor, has also fell victim to the age. As a matter of intellectual property law, you are forbidden from modifying or even repairing the machine you buy, which requires firmwear maintenance and upgrades such that John Deere can can disable it if you stop paying (or they stop supporting your model).

So too with seed. Farmers don’t buy seed. They buy the one-time right to use seed whose genetic makeup Monsanto owns, which means farmers are forbidden from reseeding or hybridizing, even where possible. Many stocks are deliberately bred sterile so that farmers have no choice but to buy more next year.

This is digital sharecropping. The new unfettered economy looks a lot like the old unfettered economy. John Deere and Monsanto have leveraged their capital position to exact rents on every crop — just like the landowners of old — and farmers, whatever of them are left, are dependent on the company store.

It is still possible to buy a tractor that’s just a tractor, but who knows for how long? Computer security expert Bruce Schneier recently tried to buy a car and found that there wasn’t a single new model on the market that didn’t come automatically connected to the IoT — the infamous internet of things.

Orwell, it seems, was an optimist. He assumed the government would mandate audiovisual listening devices in our homes. He did not imagine we would buy and install them ourselves for the sake of a few conveniences. Barely a week goes by that there’s not some creepy new revelation about Amazon Echo or Google Home. And yet, people not only keep buying them, they keep buying products that link to them, like Echo-ready headphones, which can listen to you everywhere you go rather just in your kitchen.

Liberalism places its mythical golden age in the future, which is why the science fiction of the liberal era couldn’t imagine a future that wasn’t at least basically rational, if not idyllic (like the original Star Trek), with a heavy emphasis on fairness (universal laws) and self-determination (voyages of discovery).

Conservatism places its mythical golden age in the past, whether it ever truly existed or not, which is why the science fiction of the conservative era, like “Neuromancer” and Terminator, is largely pessimistic. The future can never live up.

(The 90s are an interesting blip, brought about by the simultaneous death of communism and birth of the internet, but that’s a longer discussion.)

The 21st century has so far obliged the depressing view: 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, the housing collapse, the failure of the Arab Spring, the Snowden papers…

No sooner has China reappeared on the world stage, after a gap of 250 years, than her first Hugo Award-winner, Cixin Liu, told us in “The Three-Body Problem” that there’s no hope of getting along.

What we imagine when we imagine the future today is no future at all: the zombie apocalypse, the robot apocalypse, nuclear holocaust, environmental collapse, or any number of post-apocalyptic dystopias like “Hunger Games” or “The Road.” It seems we have trouble believing anything might work out.

We can’t make a better world if we don’t believe it’s possible.

It’s tempting to suggest that science fiction is dead — in the same way that Nietzsche said God is dead or that Lemmy said rock is dead. It isn’t that people no longer believe in God or that He isn’t an active force in their lives. It isn’t that people aren’t making and listening to rock n roll or reading and writing science fiction, even very good science fiction. It’s that those things are no longer the generative force of the age. Technology is.

We’re living in the future, which is why we no longer have a language of it. The language of the future is the language of the present. Science fiction has simply become fiction.

No new vision has emerged this century because all visions have emerged, or are emerging, including from writers outside the Western world like Liu and Nnedi Okorafor, for whom the classic myths of science fiction — a white male colonizer blasting his way through hordes of aliens — were only relevant in reverse.

This is also the distinguishing feature of our political moment, where we’re deadlocked amid cries of mutiny and no one can hold the floor. It strikes me as the cacophony before a deafening silence. But I hope I’m wrong.

November 1, 2019

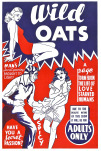

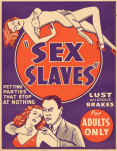

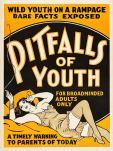

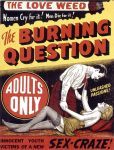

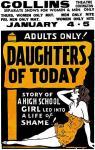

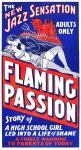

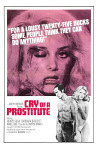

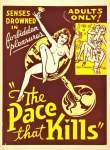

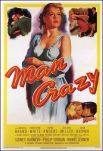

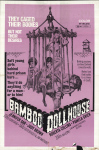

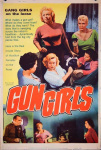

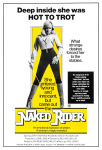

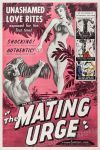

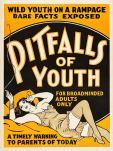

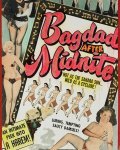

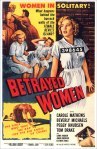

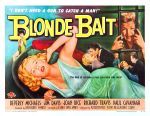

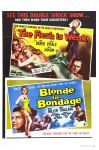

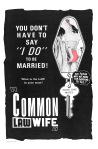

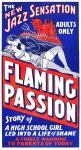

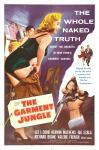

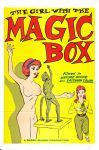

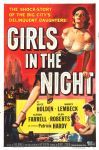

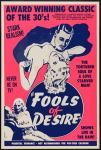

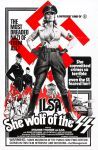

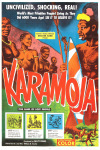

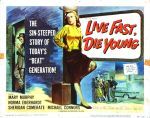

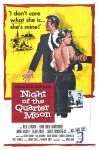

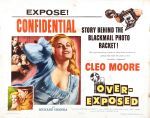

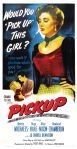

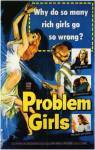

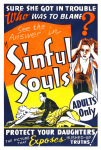

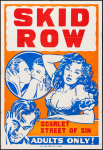

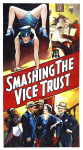

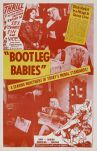

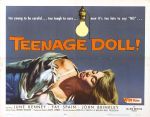

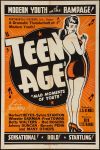

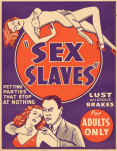

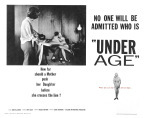

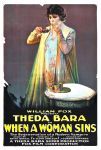

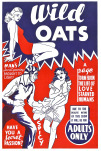

(Art) Sexploitation!

[image error]

A sexploitation film is a class of independently produced, low-budget feature film that is generally associated with the 1960s, although related films go back to 1910s and 20s:

Although not explicitly pornographic, sexploitation films filled the same role as porn, which is why they declined precipitously in the 1970s amid the rise of the hardcore movie industry.

Prior to that, sexploitation films avoided common bans on pornography in the US and abroad by posing as documentaries, or what today we might call docudramas. The first and easiest was to “document” nudist camps, which the Supreme Court ruled was fundamentally educational in nature.

After the Supreme Court ruled again in 1969 that the Swedish film I Am Curious (Yellow) was not obscene because of its “educational context,” the late 1960s and early 1970s saw a number of sexploitation films produced following this same format. These were widely referred to as “white coaters,” because, in these films, a doctor dressed in a white coat would give an introduction to the graphic content that followed, qualifying the film as “educational.” [Wikipedia]

Although not formally considered sexploitation films, pulp films of the same era tackled similar themes of teenage sex, infidelity, drugs, and violence, particularly to women, although their saucier content had to be merely implied, and of course no nudity was allowed.

These films weren’t simply hopelessly chauvinistic. Many actually indulged overt violence to women — in the interests of public safety, of course.

Not to mention racism.

Classism.

Trans-phobia.

And sheer creepiness bordering on outright pedophilia.

Oh wait, all those things are still around.

Here is a large gallery.

October 31, 2019

Halloween Decoration: Level 100

Happy Thanksgiv– er… Halloween! Tardigrade by Beau White

[image error]

Happy Thanksgiv– er… Halloween! Tardigrade by Beau White

October 29, 2019

(Fiction) A Fitting Place For Man-Eaters

[image error]

It was a fitting place for man-eaters—murderous and silent and stocked with the dead of a hundred generations. It was a fitting place to bring the departed, even those still on two feet.

“Damn, this is heavy,” Cecil grunted as the bag slipped out of his hands and fell with a splash. The big man grabbed his end of the large, limp sack and, with a heave, helped his scowling companion lift it over the next knot in the ravine. It was doubly hard in the dark and rain, and as they stumbled through ankle-high water, it bubbled and belched a foul odor.

“What the hell is in here?” Cecil had dragged the load most of the way himself, and he was starting to tire. It had been raining for days, and filth oozed from the cemetery. It pooled in foot-sized pits the pair had tracked from the car parked just past the gate all the way down to the small crevice that cut through earth. “Vernal?”

“Dog food.”

“Why are we bringing dog food all the way out here?” Cecil grunted and heaved again.

The ravine was choked thick with knotted roots and ran crooked along the base of a shallow hill dotted with sagging granite headstones and marble statues with their arms raised to the sky in silent warning.

“What is this place?” Cecil was stout with thin eyes and a fat lip. He wiped the rain from his face with his large hands. His left cheek was raked in thin, nearly healed scratches. His knuckles were well scabbed.

His companion was a stump, just over five feet with a stocky chest braced by two stubby legs like the twin barrels of a sawed-off shotgun. Vernal pointed. “There.”

A concrete slab and the yawning maw of a stone mausoleum plugged the end of the ditch. Dead vegetation hung from the opening like strips of flesh. Its open throat was deep and black and disappeared under the hill, whose sole purpose seemed to be to keep the place buried.

There was a distant rumble of thunder.

“Climb up there and help me lift this up.” Vernal pointed with a fat finger to the concrete slab, which rose three feet over the crevice.

Cecil looked up at the worn stone arch that capped the entryway. The writing wasn’t visible under the dead vines and creepers. “Why do I have to go first?”

Vernal stood straight. His eyes were round and his nose flat, as if he’d been punched repeatedly. His last shag of hair ran from the crown of his skull down the back of his head while his harelip barely covered his chipped teeth. Everything about him was filed down—everything, that is, except his forehead, which his face wore like a hat. “Cecil, how much do you weigh?” His vocal cords grated his voice like cheese. Every word was rumbling diesel.

“What?”

“It’s a simple question.”

“Uh, ’bout two-fifty I guess.”

“And how much do you think I weigh?”

“Aw, come on, Vernal.”

“How much?”

“I don’t know, maybe a buck-sixty.”

Vernal pointed to the slab. “If I climb up there, do you think I’ll be able to lift this bag?”

Cecil looked up at the entrance again, cold and dark. “Right.” He grabbed a fistful of dead vine and pulled.

“Dammit, Cecil.” Vernal quivered. “I’m soaking wet and covered in mud. You can clear the verge later.”

“Right,” Cecil repeated. He leapt onto the slab and bent to grab the front of the heavy bag. Vernal did his best to push from the bottom, but it was water-logged—swollen and fat like a tick’s butt—and hard to move.

Cecil pulled with a roar and hefted the bag over the concrete lip. The floor was wet and he slipped and fell on his ass. As the bag collapsed on the floor, something rolled out, and the stubby man snatched it quick.

“What was that?” Cecil asked.

“What was what?” Vernal gargled.

“That!” Cecil pointed at the bulge in his companion’s pocket.

“It’s nothing.”

“Was that a dick? That looked like a dick.”

“What are you talking about?

“I saw it!” Cecil protested. “It was a dick! A big, fat cock. It fell out and you picked it up.”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Yes, you did.”

“You must have been mistaken.”

“For fuck’s sake, Vernal, I wasn’t mistaken.” Cecil made quotes in the air. “Oh shit, is that blood?”

The water-logged bag lay like a leaky bladder on the concrete, sagging as its weight squeezed the water from its innards. Swirling trails of crimson flowed with the water over the lip of the floor and down into the ravine.

Cecil stepped back. “Is… is this a bag of penises?”

“No.” Vernal climbed into the mausoleum and shook his hands dry. “Well, not only penises.”

“You said it was dog food.”

“It is,” came a throaty voice from the dark.

Cecil spun around.

“You’re late.” A figure stood in shadow.

“Yes,” Vernal replied. “The weather and all.”

“Of course.” A jackal-headed man stepped forward. He walked on two legs and wore a fine linen shirt, silk vest, and trousers. He had a ragged top hat but no shoes. The fur on his feet and hands was bushy, while that about his neck was thin and gray. The spotted hyena on all fours behind him snickered and bore its teeth.

“Jackals,” Cecil breathed heavy and stepped back. He got goose bumps. “Vernal, what the fuck?”

The jackal looked at the stunted man. “You must be Vernal Wort.” He extended a long-fingered paw.

“At last we meet.” Vernal glanced down the black corridor at the greenish glint of animal eyes reflecting the faint light. He could hear growling and shuffling as he reached into his pocket and produced the stray member. He threw it to the hyena, which tore at the head. Vernal watched as it chewed the spongy insides with its back teeth. “Fresh,” he said. “Or reasonably so.”

“Oh God.” Cecil retreated farther. One hand drifted in front of his pants.

“I can assume the phallus came from the eunuch’s temple. Where did you get the rest of it?”

“The rest of what?” Cecil asked.

The jackal nodded to the bag, which was sliding back over the lip.

Vernal grit his teeth. “Cecil.”

“Huh?”

“Get the bag,” Vernal sneered at his companion as the bag slipped over the edge and fell with a splash.

“Right.” Cecil looked back at the jackal-man and his pet before hopping into the mud.

“I have my sources,” Vernal said. “All you need to know is there’s plenty more where that came from.”

“And it doesn’t bother you, Therian, trading in man-flesh?”

“No more than it bothers you eating it, aminal. And I’m no Therian.”

The jackal smiled. The corners of his lips turned up to his eyes, far wider than any human could smile. His teeth were white and sharp and shone even in the faint light. “Such disdain for the Empire. Aminals, at least, are proud of their race.”

“Are we doing business, or discussing politics?”

“Well, I can’t very well discuss politics with them.” He nodded to the eyes in the dark. “Or are you only here to feed the dogs?”

Vernal stayed silent.

The jackal stepped forward and leaned close. He was two heads taller than Vernal. “Jackals have excellent hearing, Mr. Wort. And we can smell a lie.”

Vernal didn’t try to hide his fear. There was no point. The jackals could hear his heart beat faster, could smell him sweat. “You have something for me?” he asked.

“Our deal was for five hundred pounds of man-meat. There isn’t more than two hundred in that bag.”

“Well, I didn’t come with just the bag, now did I?”

The jackal-man turned to watch Cecil struggling with the sopping load.

“He’s not quite three hundred pounds,” Vernal said, “but then I figured there’s a probably premium for freshness.”

The jackal studied Vernal for a moment. “I can see where you earned your nickname, Mr. Wort.”

“Call me Vernal.”

“You know what we will do to him, don’t you?”

“Nope,” Vernal replied. “And I don’t want to. I already know what he did to two little girls last week, and that’s enough nightmare to last a year.”

The jackal looked at the scratches on Cecil’s face and the scrapes on his knuckles. “I see.”

“No. You don’t. But I’m trying to forget it, so I’m not going to explain.”

The jackal nodded to his colleagues, who erupted from the dark, whooping and howling, and descended on Cecil, who didn’t have time to turn. He screamed, and kept screaming as vice-strong jaws sunk their teeth into his body and pulled him down the dark hall in spastic tugs.

“Vernal, please!” He begged as he slid by, arm outstretched. His dense, muscled body smeared blood in its wake.

“Save his face for me,” the jackal called to his pack.

Vernal held out his hand. “My payment.”

The jackal reached into his vest pocket and produced a brass key, long and tarnished and studded with movable teeth like a combination lock. Vernal reached out but the jackal-man pulled back. “Why is this key so important?”

Vernal said nothing. He waited.

“Forget that the Empire would boil you alive for this, publicly. What about Pimpernel?”

“Who?” Vernal feigned.

“Erasmus Pimpernel. You outbid him for this key.”

“Oh?”

“He offered a small fortune. But as you intelligently surmised, Imperial money is just paper to us.”

“Your concern is touching, but I have no idea what you’re talking about.” Vernal held out his hand again. “My payment, please.”

The jackal bared his teeth and handed the key to the little man. “As you wish.”

“If you’re so worried about this fellow Pimpernel, why didn’t you just give the key to him?”

“Well, you know what they say about enemies of friends with enemies.”

“I wouldn’t know.” Vernal wrapped the key in cloth, reached into his pants, and stuck it between his ass cheeks. “I don’t have friends,” he said with a grunt.

A long, gurgling scream echoed from the dark and faded into a slobbering moan, a blubbering, begging lament.

“I can see that.” The jackal licked his lips. As his tongue swung around his narrow muzzle, a drop of saliva fell to the ground. “I must confess, I’d considered eating you. But any man who isn’t afraid of Erasmus Pimpernel . . .”

“Frankly,” Vernal climbed down into the ravine. “I’m more worried about my poor sister.”

“Your sister?”

“Yeah.” Vernal turned. “Last week, her two little girls were killed, and now,” Vernal nodded down the dark tunnel, “her husband seems to have gone missing. Good day.”

“Good day, Mr. Wort.”

The first chapter of the first book I ever published, FANTASMAGORIA, opens with a literal bag of dicks. That says something.

cover image by asahisuperdry