Matt Dembicki's Blog, page 9

February 17, 2012

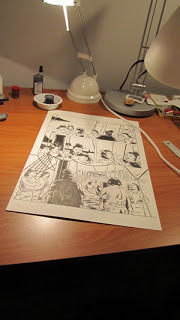

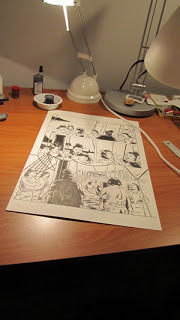

Inking, inking, inking

My current "big project" is inking and lettering a graphic novel written by Rebecca Goldfield and pencilled by Mike Short. It'll be colored by Evan Keeling (who colored my upcoming graphic novel Xoc: The Journey of a Great White).

Published on February 17, 2012 20:30

January 29, 2012

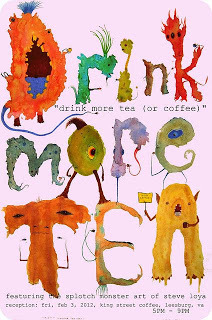

The 'splotch monster' master

Artist and colleague Steve Loya is having a mini-exhibit of his art, including his "splotch monsters," next Friday, Feb. 3, at King Street Coffee in Leesburg, Va. I hope to make it; you should, too, if you're in the area. (I believe Steve is going to have hands-on activities for visitors.)

Published on January 29, 2012 21:28

January 25, 2012

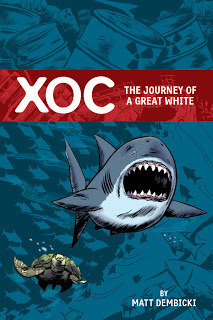

'Xoc' cover

And here's the full cover. I'm thrilled with how this book has turned out. Can't wait for it to hit the shelves! (BTW, Evan Keeling did a wonderful job on the colors.)

Published on January 25, 2012 18:52

January 13, 2012

'Xoc: The Journey of a Great White'

My new graphic novel from Oni Press about a great white shark will be available at San Diego Comic Con in early July and then at bookstores and comics shops on July 25. Here's a small part of the expected cover.

Published on January 13, 2012 12:52

November 10, 2011

Aesop Prize

Dang, I can't believe I haven't posted something in two months! But this is worth the wait: Trickster has been awarded the 2011 Aesop Prize!

Published on November 10, 2011 17:36

September 6, 2011

Next Project

Published on September 06, 2011 20:29

August 25, 2011

'Trickster' essay

Below is an essay about

Trickster

, written by a student of Trickster contributing writer Michael Thompson, who teaches at a New Mexico high school. Forty percent of the school's students are Navajo. Enjoy this excellent piece!

Trickster CommentaryClass of 2012

My interest in graphic novels started at an early age. Not content with the picture books found in my local library, I wandered around. I found a comic book teaching history, and I started reading. Here was a new medium that I could delve into, I could understand—the artist's use of panels, colors, art, words, balloons, and dialogue merged together better than any picture book or "book" book I could read.

Since then I have read graphic novels, comic books, everything in the medium, varying in subjects from historical non/fiction, to famous literary adaptations, fantasy, foreign stories (French, German, Japanese, African, etc.), and biographic/ autobiographical, such as the famous Maus and Persepolis books.

My first experience with Trickster was when Mr. Thompson, my English teacher, gave me the book to review. I proceeded to kidnap the thing and reread it over and over again. I received my own copy from an older friend, a female director of a Native American Prep College program. She knew I liked comics, from reading my own, and gave it to me.

Trickster would have to be the first graphic novel of its kind that I have ever seen. It reminded me of an old Coyote stories book that my grandmother used to own, which whenever I visited her, I would reread with fervor, wanting to etch those stories into my mind. I am very familiar with Trickster stories, as my own graphic novel deals with the kitsune, Japan's own trickster fox. As a cartoonist myself, I felt that this book could be the first of many like it, increasing awareness of Native American mythology, especially for young Native Americans who cannot always hear the tales told to them by an elder or read to them in a hard-to-get book. Too many stories have slipped into obscurity, only to be taken over by other mythologies, to be forgotten, to be lost forever.

I believe that the graphic novel format matches the stories very well. It inspired me to try to get rid of that—that line between graphic novels and novels, the prejudiced line that says such books are for kids. If that line were to disappear, people could open Trickster and see it for what it really is—a great book. It teaches lessons, has a variety of Trickster characters, wonderful art and writing by awesome collaborations between artist and writer. I would very much like it if people were to pick up my book one day and feel the same, as it is a very new take on the "monsters coexisting with humans" and "existence of mythological creatures in the real world" concept.

People need to realize that such stories come from long years of oral tradition and worship, religions existing before the Bible, where children were not taught the words of the book, but actions of others with creatures mixed in. Early Grimm's tales were full of violence, imagery, and lessons. Native American stories were teaching how to live a life peacefully, Greek myths of gods and goddesses of doing things we shouldn't do, African songs telling of people's close relationship with the animals, stories from all around the world, and each and every one of them told an important lesson, like Aesop's fables.

If more books like Trickster came out, they could tell all of the stories, teaching each indigenous people's own history, culture, and imagination, giving way to new interpretation and collaboration, uniting elder storytellers with the new, younger generation of artists. I feel that Trickster achieved this aspect very well, especially in the interactions with different characters.

Some stories followed the traditional narrative point-of-view, with illustrative art matching it wonderfully in the tradition of older children's book. Some, however, took a new path in third-person, or even first-person point-of-view, as the story was behind the character's dialogue and before-mentioned interactions, with stylized art matching this new outlook. In fact, it brings me to the collaboration of pictures and words, letters and brushstrokes.

If you were to just read the words of Trickster in the stories aloud, no doubt they would sound like your elders telling a story, as they perfectly match oral traditions. And if you were to just look at the pictures of Trickster, you could get the gist of the story, a silent pantomime with exaggerated body language and expression. Combine the two, and you get the full effect of the story. Trickster, in my opinion, orchestrated this wonderfully into a satisfying opus of creativeness. Nothing before has matched this high award in my mind, save for HBO Kid's World Fairytales, a short-lived but well remembered anthology of stories from around the world, brought to life in animated shorts using sand, traditional cel, painting, digitized, and stop-motion animation.

In Trickster, some of the art varies so, from realistic to cartoony. Each of the stories looks deceptively simple, but you can tell that the collaboration did well—from the well-arranged placement of panels to match the near-the-climax plotlines, character design showing the personality of each Trickster before he or she even utters a single word, and word balloons matching the pace of the dialogue perfectly.

One example of this would have to be artist Meagan Baehr's and writer Joyce Bear's "How the Alligator Got His Brown Scaly Skin." It is both my favorite story and example of the brilliance of graphic novels. We are first shown, in a large, square panel, the alligator with "beautiful, smooth, bright yellow skin": from his smirk and furrowed brow, we can tell that alligator is a vain one, as are all players in the Trickster tales that get their comeuppance due to a fatal flaw such as pride, vanity, or cruelty.

In the next series of panels, we are told that Alligator is indeed "selfish and stingy with his water," as he is a creature of the rivers. A deer, looking for relief, walks up to drink, only to be surprised with classic dinner plate eyes, Alligator's wide mouth. From there on, Alligator is a stingy yet beautiful creature that scares the others, who soon come up with a council for what to do with Alligator, coming up with "teaching him a lesson," except that "he is so big and tough!"

Each of the pages follows the classic plotline: the setting, "rivers and streams of the southeast." Then, the introduction of the characters, Alligator the antagonist, Rabbit the Trickster, and the other animals such as Deer, Raccoon, Turtle, Owl, and Skunk. The rising action follows: "We need to do something about Alligator!" Conflict swiftly follows: "You think you are really tough, don't you, Alligator?" "Yes, I am tough, tougher than you!"

Climax finally comes when Alligator meets "Mr. Trouble," aka fire, which promptly burns Alligator's yellow skin into "his brown, scaly skin." Falling action is when Alligator flees land, staying in the water because he "is so ashamed." The lesson, or resolution, comes afterward: "But Rabbit is always there to remind Alligator that if he does not behave, he will call Mr. Trouble to deal with him again." Thus, ends the story, teaching an important lesson.

As for the art, it is very lovely—Beahr's careful use of watercolor lends a gentle mood to the story, and Alligator's new brown skin is a nice contrast to the beauty of the Southeast. Also, minimalistic detail only betrays the expressions, actions, and poses of the characters that are needed to understand the story. The rounded panels show Rabbit's early escapade with Mr. Trouble, and the boxes match the pace of the story well, showing the character's faces in great detail at a comfortable distance, with the background always behind of them, never more dazzling than the characters themselves. And I just love the way Beahr paints fire. I could go on and on, but I should talk about the educational impact that Trickster could deliver.

I strongly believe that Trickster could be used as an effective teaching tool. Each story contains a lesson, by-the-book story devices and diagrams, and provides a visual example for more pictorial learners. Also, and perhaps the most important, Trickster would greatly benefit many younger Native Americans who, sadly, do not know their own tribe's stories.

Often they are limited by taboo (I.e., the non-telling of Coyote stories until wintertime) or the loss of a storyteller, forced to look for such stories and finding very few. Trickster could very much take care of this situation and help a tribe's own diminishing of culture by telling these stories in graphic novel format. Hopefully, it would prompt students to look up the original stories, or to look for storytellers in their community, or even try to revive the telling of such stories. If possible at my own school, I myself would like to lend a hand in doing such things. Of course, for me, it would have to be in the format of a graphic novel.

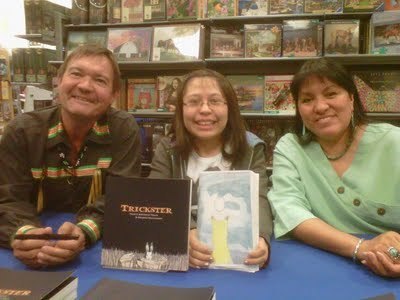

Michael Thompson, Kayla Shaggy (with her graphic novel),and contributing Trickster writer Eldrena Douma at a Trickster signing.

Trickster CommentaryClass of 2012

My interest in graphic novels started at an early age. Not content with the picture books found in my local library, I wandered around. I found a comic book teaching history, and I started reading. Here was a new medium that I could delve into, I could understand—the artist's use of panels, colors, art, words, balloons, and dialogue merged together better than any picture book or "book" book I could read.

Since then I have read graphic novels, comic books, everything in the medium, varying in subjects from historical non/fiction, to famous literary adaptations, fantasy, foreign stories (French, German, Japanese, African, etc.), and biographic/ autobiographical, such as the famous Maus and Persepolis books.

My first experience with Trickster was when Mr. Thompson, my English teacher, gave me the book to review. I proceeded to kidnap the thing and reread it over and over again. I received my own copy from an older friend, a female director of a Native American Prep College program. She knew I liked comics, from reading my own, and gave it to me.

Trickster would have to be the first graphic novel of its kind that I have ever seen. It reminded me of an old Coyote stories book that my grandmother used to own, which whenever I visited her, I would reread with fervor, wanting to etch those stories into my mind. I am very familiar with Trickster stories, as my own graphic novel deals with the kitsune, Japan's own trickster fox. As a cartoonist myself, I felt that this book could be the first of many like it, increasing awareness of Native American mythology, especially for young Native Americans who cannot always hear the tales told to them by an elder or read to them in a hard-to-get book. Too many stories have slipped into obscurity, only to be taken over by other mythologies, to be forgotten, to be lost forever.

I believe that the graphic novel format matches the stories very well. It inspired me to try to get rid of that—that line between graphic novels and novels, the prejudiced line that says such books are for kids. If that line were to disappear, people could open Trickster and see it for what it really is—a great book. It teaches lessons, has a variety of Trickster characters, wonderful art and writing by awesome collaborations between artist and writer. I would very much like it if people were to pick up my book one day and feel the same, as it is a very new take on the "monsters coexisting with humans" and "existence of mythological creatures in the real world" concept.

People need to realize that such stories come from long years of oral tradition and worship, religions existing before the Bible, where children were not taught the words of the book, but actions of others with creatures mixed in. Early Grimm's tales were full of violence, imagery, and lessons. Native American stories were teaching how to live a life peacefully, Greek myths of gods and goddesses of doing things we shouldn't do, African songs telling of people's close relationship with the animals, stories from all around the world, and each and every one of them told an important lesson, like Aesop's fables.

If more books like Trickster came out, they could tell all of the stories, teaching each indigenous people's own history, culture, and imagination, giving way to new interpretation and collaboration, uniting elder storytellers with the new, younger generation of artists. I feel that Trickster achieved this aspect very well, especially in the interactions with different characters.

Some stories followed the traditional narrative point-of-view, with illustrative art matching it wonderfully in the tradition of older children's book. Some, however, took a new path in third-person, or even first-person point-of-view, as the story was behind the character's dialogue and before-mentioned interactions, with stylized art matching this new outlook. In fact, it brings me to the collaboration of pictures and words, letters and brushstrokes.

If you were to just read the words of Trickster in the stories aloud, no doubt they would sound like your elders telling a story, as they perfectly match oral traditions. And if you were to just look at the pictures of Trickster, you could get the gist of the story, a silent pantomime with exaggerated body language and expression. Combine the two, and you get the full effect of the story. Trickster, in my opinion, orchestrated this wonderfully into a satisfying opus of creativeness. Nothing before has matched this high award in my mind, save for HBO Kid's World Fairytales, a short-lived but well remembered anthology of stories from around the world, brought to life in animated shorts using sand, traditional cel, painting, digitized, and stop-motion animation.

In Trickster, some of the art varies so, from realistic to cartoony. Each of the stories looks deceptively simple, but you can tell that the collaboration did well—from the well-arranged placement of panels to match the near-the-climax plotlines, character design showing the personality of each Trickster before he or she even utters a single word, and word balloons matching the pace of the dialogue perfectly.

One example of this would have to be artist Meagan Baehr's and writer Joyce Bear's "How the Alligator Got His Brown Scaly Skin." It is both my favorite story and example of the brilliance of graphic novels. We are first shown, in a large, square panel, the alligator with "beautiful, smooth, bright yellow skin": from his smirk and furrowed brow, we can tell that alligator is a vain one, as are all players in the Trickster tales that get their comeuppance due to a fatal flaw such as pride, vanity, or cruelty.

In the next series of panels, we are told that Alligator is indeed "selfish and stingy with his water," as he is a creature of the rivers. A deer, looking for relief, walks up to drink, only to be surprised with classic dinner plate eyes, Alligator's wide mouth. From there on, Alligator is a stingy yet beautiful creature that scares the others, who soon come up with a council for what to do with Alligator, coming up with "teaching him a lesson," except that "he is so big and tough!"

Each of the pages follows the classic plotline: the setting, "rivers and streams of the southeast." Then, the introduction of the characters, Alligator the antagonist, Rabbit the Trickster, and the other animals such as Deer, Raccoon, Turtle, Owl, and Skunk. The rising action follows: "We need to do something about Alligator!" Conflict swiftly follows: "You think you are really tough, don't you, Alligator?" "Yes, I am tough, tougher than you!"

Climax finally comes when Alligator meets "Mr. Trouble," aka fire, which promptly burns Alligator's yellow skin into "his brown, scaly skin." Falling action is when Alligator flees land, staying in the water because he "is so ashamed." The lesson, or resolution, comes afterward: "But Rabbit is always there to remind Alligator that if he does not behave, he will call Mr. Trouble to deal with him again." Thus, ends the story, teaching an important lesson.

As for the art, it is very lovely—Beahr's careful use of watercolor lends a gentle mood to the story, and Alligator's new brown skin is a nice contrast to the beauty of the Southeast. Also, minimalistic detail only betrays the expressions, actions, and poses of the characters that are needed to understand the story. The rounded panels show Rabbit's early escapade with Mr. Trouble, and the boxes match the pace of the story well, showing the character's faces in great detail at a comfortable distance, with the background always behind of them, never more dazzling than the characters themselves. And I just love the way Beahr paints fire. I could go on and on, but I should talk about the educational impact that Trickster could deliver.

I strongly believe that Trickster could be used as an effective teaching tool. Each story contains a lesson, by-the-book story devices and diagrams, and provides a visual example for more pictorial learners. Also, and perhaps the most important, Trickster would greatly benefit many younger Native Americans who, sadly, do not know their own tribe's stories.

Often they are limited by taboo (I.e., the non-telling of Coyote stories until wintertime) or the loss of a storyteller, forced to look for such stories and finding very few. Trickster could very much take care of this situation and help a tribe's own diminishing of culture by telling these stories in graphic novel format. Hopefully, it would prompt students to look up the original stories, or to look for storytellers in their community, or even try to revive the telling of such stories. If possible at my own school, I myself would like to lend a hand in doing such things. Of course, for me, it would have to be in the format of a graphic novel.

Michael Thompson, Kayla Shaggy (with her graphic novel),and contributing Trickster writer Eldrena Douma at a Trickster signing.

Published on August 25, 2011 14:26

August 21, 2011

Comics-making workshops

I've got a few local comics-making workshops coming up. Here are a couple open to the public:

Cool Cartooning

1-hour program for school-age children

Sept. 12, 3 p.m.

Centerville Regional Library

Centerville, Va.

Making Comics

1-hour program for school-age children

Oct. 3, 3:30 p.m.

Thomas Jefferson Library

Falls Church, Va.

Call the respective libraries to register.

Cool Cartooning

1-hour program for school-age children

Sept. 12, 3 p.m.

Centerville Regional Library

Centerville, Va.

Making Comics

1-hour program for school-age children

Oct. 3, 3:30 p.m.

Thomas Jefferson Library

Falls Church, Va.

Call the respective libraries to register.

Published on August 21, 2011 08:51

August 20, 2011

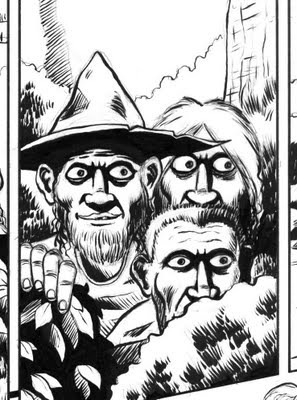

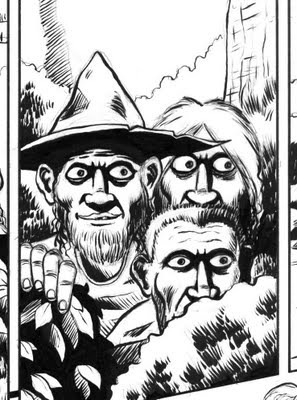

Panels from 'Plastic Farm'

Here are two panels from an ongoing story I'm working on for Rafer Roberts' Plastic Farm. (It's a creepy story, if you can't tell.) The first panel is inked and still has the pencil sketches on it; the second panel is finished, complete with a graywash.

Published on August 20, 2011 04:58

August 14, 2011

Dinosaur Land!

Yesterday we took a trip to Dinosaur Land near Front Royal, Va., which is run out of a gift shop/convenience store in the middle of nowhere. It's a bit run down--could use a fresh coat of paint--and isn't used to its full potential, but it provides some cheeky fun. (I could see it as a mini-golf area with a snack bar and even an arcade. Maybe someday when I have a few more bucks in my pocket....)

Here are some photos:

Here are some photos:

Published on August 14, 2011 05:41